P A R T VII

![]()

Drupal Community

Chapter 35 gives the story of Drupal’s beginnings as an open source project and some key events to its development into the thriving community it is today.

Chapter 36 tackles what it takes to make a living with Drupal, including taking a hard look at problems with Drupal software—and suggests ways you can mutually sustain your success and Drupal’s success.

Chapter 37 goes over maintaining a project shared with the world on Drupal.org and making use of the Git revision control system.

Chapter 38 caps off the book with a discussion of effective ways to contribute back to Drupal to make the software you work with, and the community you work in, better. And, perhaps, help make the world better.

C H A P T E R 35

![]()

Drupal’s Story: A Chain of Many Unexpected Events

“For me the history of Drupal is a chain of interesting surprises.”

—Dries Buytaert, Drupal Founder and Project Lead

I considered titling this chapter “History,” but decided that that would be misleading. Even though the Drupal project is only ten years old at the time of this printing, a complete history of Drupal would fill hundreds of pages and document the experiences of literally hundreds of thousands of people.

And in the interest of full disclosure, if you are looking for an exhaustive biography of key contributors, you will have better luck checking out their profile pages. While many key contributors are fascinating, intelligent characters whose decisions, actions, and beliefs undoubtedly left their mark on the community that so many people worldwide have come to know and love, this history is not a story about the People-with-a-capital-P who shaped Drupal.

It is instead a story about the events that shaped Drupal, and how the community as a whole responded to those events. Speaking of the community...

As an outside observer, I have come to feel that the truly amazing thing about Drupal is its appeal to a bizarrely wide range of users. Drupal users run the gamut from hobby hackers to entrepreneurs, radical grassroots organizers to national governments, FOSS evangelists to corporate strategists—and the community includes a multitude of entities and individuals who combine traits from all of the above.

It is completely just to say that the quality and flexibility of Drupal’s code explains its wide appeal, and that it should come as no surprise that an elegant, adaptable, and useful technology will have an impressive range of applications...

...but it is equally just to point out that Drupal is a collaboratively-produced enterprise. Members of every group described above from every inhabited continent must communicate, work together, and rely on one another in order to get the most of what they want from the software—and in so doing, push the project forward as a whole. What has made this implementation of open source values on a huge scale possible? What is it about the Drupal project that inspires this type of devotion, which has in turn resulted in its phenomenal success?

The answer: the aforementioned chain of many unexpected events,1 and the community’s response.

This chapter will provide snapshots of a few events that shaped how and why the community survived and grew, and in so doing, will hopefully capture a little of the flavor that defines Drupal (though I will leave it up to the reader to define for themselves exactly what that flavor is). After a brief reccounting of Drupal’s origins, the first section describes events that resulted in Drupal attracting the critical mass of developers it needed to thrive. The next two sections outline the events that determined the shape of Drupal’s infrastructure, and how that infrastructure balances the open source values that give Drupal its strength with the ability to support a wide range of commercially-viable applications.

The Original Accident

The experiment that we now know as the Drupal project began in 1998, when Dries Buytaert, a Belgian undergraduate student seeking his Licentiate in Computer Science at the University of Antwerp, began construction on a local area network to connect his dorm-mates (and avoid the high cost of Internet access at the university). The message boards that Dries created allowed his fellow computer science students to discuss the latest in internet technology and to just plain keep in touch.

The latter is important because it was this sense of community that inspired Dries, upon his graduation and move from the dorms, to keep the discussions going by moving the internal web site to the Internet. On April 28, 2000, drop.org was born.

![]() Note Just in case there are any readers out there who have somehow managed to escape familiarity with the origins of Drupal’s name, here’s the condensed version: In the beginning, there was a typo. And Dries looked upon his typo, and he saw that it was good...so he went with it. When registering his new site’s domain, Dries meant to type an abbreviation of the Dutch word dorpje (meaning village), but misspelled it as the English word drop. Later, when naming the software, he back-translated drop into Dutch (druppel), which he then spelled phonetically (in English) as drupal.

Note Just in case there are any readers out there who have somehow managed to escape familiarity with the origins of Drupal’s name, here’s the condensed version: In the beginning, there was a typo. And Dries looked upon his typo, and he saw that it was good...so he went with it. When registering his new site’s domain, Dries meant to type an abbreviation of the Dutch word dorpje (meaning village), but misspelled it as the English word drop. Later, when naming the software, he back-translated drop into Dutch (druppel), which he then spelled phonetically (in English) as drupal.

In a move that would define the character of the Drupal community forever after, Dries, rather than trying to implement the deluge of suggestions, complaints, and advice himself, chose to make the software available to anyone, for free, under the GNU General Public License. This meant that anyone who was willing to put their time and effort into trying out their ideas was able to experiment with the code that would become Drupal at will—providing they agreed to make the results of their experiments just as freely available to others. On January 15, 2001, the Free and Open Source Software (FOSS) movement gained a new member with the official release of Drupal 1.0.

While it was originally intended that the content of the discussions on drop.org be about Internet technologies in general, the commentary quickly began to trend toward the very specific—as in, the software powering drop.org web site itself.

Shortly after Drupal 2.0 was released on March 15, 2001, Dries decided to provide a place for all of the specifically Drupal-related activity that had been overwhelming the drop.org site, and so drupal.org was born.

_____________________

1 Dries Buytaert uses the phrase “a chain of many unexpected events” to describe Drupal in an interview with Noel Hidalgo, 26 July 2007, “episode 13–dries on drupal,” http://luckofseven.com/vlog/episode13.

Drupal Gains a Foothold

Drupal continued to evolve in relative obscurity until early 2002, when Dries initiated a relationship with Jeremy Andrews, owner and operator of kerneltrap.org. A news site reporting on issues relating to Linux Kernel and the FOSS world at large, kerneltrap.org would periodically go down under an onslaught of traffic due to a mention on the popular technology-related news site slashdot.org/. Dries contacted Jeremy and suggested Drupal as an alternative to PHP-Nuke, and Jeremy, after converting kerneltrap.org to Drupal 3.0.2 on February 14, 2002, developed the throttle module (which was eventually included in Drupal 4.1 core).

While the throttle module “is little more than a Band-Aid, attempting to work around a problem rather than solving it,”2 and was removed from Drupal 7 core, the impact of that early relationship was significant. Jeremy would go on to be an active member of the Drupal community for many years, with over 4400 commits to his credit. But more relevant to the purposes of this chapter, he reported on his early conversion to and work with Drupal on kerneltrap.org itself. The publicity generated by this most sincere form of endorsement has been identified by Dries as something that “opened the eyes of many other people in the technical world”3 to Drupal’s unique capabilities.

If the 2002 mention on kerneltrap.org represents Drupal’s “coming out” to the world of techies, July of 2003 represents the beginning of Drupal’s “coming out” to the world at large. While the Drupal community was hacking its way through versions 4.2, 4.3, and 4.4, a group of politically active young people were using the still relatively obscure content management system in an attempt to get a relatively obscure candidate elected president of the United States.

While candidate Howard Dean did not get elected, he did make it on to the national scene in a big way—thanks in part to the organizing capacity of the Drupal software and the dedication of the activist/developers who constructed the web sites that drove the campaign. While the organizers used Drupal software to create DeanSpace, a site used to connect and organize Dean volunteers around the United States and therefore expand exponentially the number of people the campaign reached, the campaign’s expansion caused the Drupal software to undergo its own exponential growth.

As more and more Drupal-run Dean sites popped up, the number of developers constructing modules to meet the needs of these sites grew as well. David Cohn, in writing about this period of Drupal’s history, uses the figure of a 300% increase in created content on drupal.org. This reciprocal push of development continued even after Dean’s campaign collapsed; in fact, the end of the campaign ushered in a period of rapid expansion of Drupal into a variety of grassroots and not-for-profit applications, much of it driven by former Dean-volunteer Drupal developer talent. On July 23, 2004, it was officially announced that the DeanSpace was dead, and CivicSpace, “the first company with full time employees that was developing and distributing Drupal technology”4 had begun. Advomatic, Chapter Three, and Echo Ditto are examples of other Drupal-based companies founded by Dean volunteers that continue to contribute significantly to the Drupal community.

_____________________

2 Tag1 Consulting, Inc., “Section 3: The Throttle Module,” http://books.tag1consulting.com/scalability/drupal/performance/throttle

3 Dries Buytaert, 26 July 2007, interview with Noel Hidalgo, “episode 13 – dries on drupal,” http://luckofseven.com/vlog/episode13.

4 DigiDave, Drupal Nation: Software to Power the Left, http://blog.digidave.org/2008/12/drupal-nation-software-to-power-the-left

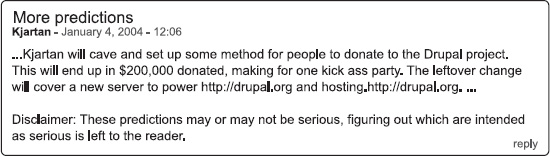

Figure 35-1. 2004 New Year’s Eve prediction by Neil Drumm, future co-founder of CivicSpace and Drupal core developer

Oh, That’s How You Say Your Name!

Seven months after all of this very visible and large-scale activity was taking place on the North American continent, on the other side of the Atlantic Drupal was experiencing the advent of a tradition that has become definitive to the character of the culture itself, as ultimately significant as the events of 2004 (though on a far more intimate scale).

![]() Tip It involved lots of beer and power strips.

Tip It involved lots of beer and power strips.

On February 26, 2005, a major milestone occurred: what is widely recognized as the first Drupal Conference (though technically, the first stand-alone DrupalCon would not occur for another seven months). FOSDEM, or the Free and Open Source Developers’ European Meeting, is a conference that is still being held annually in Brussels, Belgium, “organized by volunteers to promote the widespread use of Free and Open Source software” and to “provide developers with a place to meet.”5 FOSDEM 2005 was attended by between 3,000 and 3,500 people from all over the world. In addition to scheduled speakers and short project presentations in the form of lightning talks, FOSDEM 2005 hosted eighteen developers’ rooms, including Drupal’s.6

DrupalCons, however, are not the tradition to which the hint above refers. The really significant event occurred during the two days prior to FOSDEM.

On February 24 and 25, 2005, four months after the release of Drupal 4.5, Drupalistas gathered in Antwerp, Belgium for the first official Drupal developer sprint. Twenty-six Drupal developers from eleven countries met up to work collaboratively (and face to face) on issues that sprint organizers had identified as needing concentrated attention prior to the meet-up. Roughly 80% of these developers traveled from outside of Western Europe for the event, with twelve of the twenty-six coming from different continents entirely.

The tradition of flying out in order to meet up was born.

_____________________

5 FOSDEM, About page, www.fosdem.org/2010/about/fosdem

6 FOSDEM, Archive of 2005, http://archive.fosdem.org/2005/

The Extended Weekend from Hell

Drupal 4.6 was released April 15, 2005. By any measure or definition, the Drupal community was continuing its trend of rapid expansion: by July 2005, there were 26,772 users and 455 service providers registered to drupal.org. In practical terms, this meant that a massive number of people were affected by the events of July 7-11, 2005—what Steven Wittens dubbed “the Extended Weekend from Hell.”8 On July 10, users attempting to log on to drupal.org were greeted with the following message: “http://drupal.org temporarily offline. We can’t get the server back online without help from our hosting company, and after 48 hours they still have not responded to our support requests.”9

Steven provided a (less terse/stressed/desperate sounding) blow-by-blow description of events in his July 12 News and Announcements drupal.org post on the subject: “Thursday evening, this server was hacked. One of the other sites on our server provided the hole through which the hackers entered; it appears someone wanted to turn us into a warez FTP, but completely messed it up instead. We discovered the intrusion quickly and were able to regain control of the server soon afterward. However, the entire incident occurred only a few hours before a scheduled power outage at our current ISP; problems with remote administration and the lack of install media meant we were unable to fix the server remotely. Over the weekend we called to try and rectify the situation, but due to miscommunication with our ISP we had to wait until Monday morning before we could reinstall the OS and get the server purring again.”10

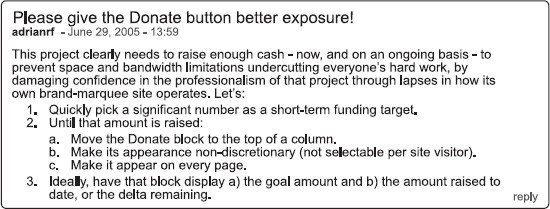

While the server crash may have hit drupal users like a slap to the face, the community was by no means unaware that problems with infrastructure could prove to be an issue, as illustrated in Figure 35-2.

Figure 35-2. The Drupal community was aware that problems with infrastructure could be an issue.

Dries had already prepared for publication prior to the server crash a message that Charlie Lowe posted to the main page of drupal.org on July 10, addressing the need to get a new server. At the time of the crash, drupal.org was running on a Pentium Xeon 3Ghz server with 1GB of RAM that it shared with approximately 20 other sites; Drupal veteran Kjartan Mannes (http://drupal.org/user/2) both maintained the server and footed the bill.

_____________________

7 Groups.Drupal, Growth Charts, http://groups.drupal.org/node/1980

8 Drupal, “Restoring Drupal.org and Murphy’s Law,” http://drupal.org/node/26545

9 Internet Archive WayBack Machine, http://web.archive.org/web/web.php, http://www.drupal.org/

10 Drupal, “Restoring Drupal.org and Murphy’s Law,” http://drupal.org/node/26545

In the month of June alone, according to Dries’ post “Help Drupal.org Buy a Dedicated Server,”drupal.org generated 100GB of traffic, serving over 3 million pages; in his words, “our current server doesn’t cut it anymore.” The message to the Drupal community begins “Quite a few people have pointed out that drupal.org has been slow lately. We know it’s been slow, and have been working on optimizing drupal.org... The fact remains that as the result of Drupal’s growing popularity, the server is saturated pretty much all day. This explains drupal.org’s poor performance.”11

The post goes on to outline a plan for moving drupal.org to a new server hosted by Oregon State University’s Open Source Lab (OSUOSL, OSL). The Open Source Lab was officially created in January of 2004 with the stated mission of “help[ing to] accelerate the adoption of open source software across the globe and aid[ing] the community that develops and uses it.”12 These fairy godmothers of FOSS had come to the aid of Drupal veteran Jeremy Andrews two months prior to the drupal.org server meltdown; when Jeremy found himself looking for a new host for http://kerneltrap.org, OSL was the first organization that he contacted.

As Associate Director of OSL, Scott Kveton explained to Jeremy, “The goal of the Open Source Lab is to bring FOSS communities together and so by doing promote cross-pollination of ideas and people to help create an atmosphere of innovation around open source.” Particularly well-positioned to meet this goal, by mid-2005 OSL was already hosting projects such as Arklinux, Debian GNU/Linux, Freenode.net, Gentoo Linux, the Mozilla Foundation, the PowerPC Kernel Archives, and SPI.

OSL gathered this impressive list of participants mostly by keeping their ears to the FOSS grapevine and offering their assistance when and where it was needed; as Scott explained to Jeremy, the OSL team would hear that “such-and-such project had a machine that died and needs help or so-and-so is reaching the limits of their existing infrastructure and needs help.”

This pretty neatly describes where Drupal was in June of 2005. Drupal also passed the selection criteria that the OSL staff used to evaluate prospective hostees: it was community-focused; it had “committed, energetic, and most importantly, realistic leadership;” its community would interact well with those of the projects already hosted at OSL; it would use the services provided by OSL to help its community grow; and the OSL’s resources and services would enable the community to focus on rapid innovation (rather than simply keeping the lights on).

Let’s face it, open source is gaining traction everywhere. With its success comes additional drains on already strapped resources. We want to be an option for these open source projects that don’t want to be indentured servants of the big companies that want to provide help. We’re not anti-company or anti-people-making-money-from-open-source; we just know that projects want to ensure the future of their communities and so are very careful about who they partner with. We know this will take time and as with everything in open source; it’s all about the relationships we develop.

—Scott Kveton, 200513

Only a few weeks prior to Drupal’s server meltdown, the conditions of the deal had already been worked out: OSL would provide free hosting—rack space, bandwidth, power, domain name service, database, back-ups, and mail relay. All the Drupal community would have to do was provide the hardware.14 The price tag on the desired equipment was US$3,000.

_____________________

11 Internet Archive WayBack Machine, http://web.archive.org/web/web.php, www.drupal.org/

12 KernelTrap, “KernelTrap: New Home At The Open Source Lab,” http://kerneltrap.org/node/5083

13 KernelTrap, “KernelTrap: New Home At The Open Source Lab,” http://kerneltrap.org/node/5083

The call for donations was posted on the temporary main page of drupal.org (the only one accessible at the time) on July 10, 2005. Shortly after that, a piece explaining Drupal’s plight was posted to slashdot.org/15. Sixteen hours after the initial drupal.org posting, the US$3,000 target had been reached and exceeded. By July 12, the Drupal community had donated more than US$10,000 and Drupal organizers had more than enough money to meet their needs, literally. Without a foundation or any other formal not-for-profit status, Drupal’s bounty was potentially taxable—and sitting in the PayPal account of a private individual. This situation emphasized another long-recognized but long-postponed need of the community, and the formation of an Association became an acknowledged priority.

The generosity that the FOSS community exhibited toward Drupal during the Extended Weekend from Hell did not end with the contributions of OSL and private donors. Tim Bray, who Dries describes as “Sun Microsystems employee, W3C member, co-inventor of XML, and Drupal fan”16 came across the slashdot.org/ piece describing Drupal’s situation (which had been posted at 3:39 p.m. on Sunday, July 10). Sympathetic, Tim passed the story up the chain of command at Sun, along with the request that something be done to help.17 It was still Sunday when Dries received the e-mail from Hal Stern, Software CTO of Sun, informing him that Drupal was the proud new owner of a free Sun Fire V20z server. Paperwork was signed on Monday, and by Tuesday, the server arrived at its new home at OSL.18

Amusing side note: Dries Buytaert of Drupal wrote wondering “under what terms we’d get such machinery from Sun” and Hal wrote back saying a mention on the site would be nice, “and no offense, but the legal cost of any more ‘terms’ than above exceeds our cost of the hardware.”

—Tim Brays19

By July 19, all of the donations had been transferred to OSL (and out of Dries’ PayPal account), and implementation of the infrastructure proposal developed by the team at OSL and FireBright (CEO Jonathan Lambert) could begin with the purchase of three Dell PowerEdge 1850 1Us. By August 25, the team including Kjartan Mannes, Corey Shields (OSL Infrastructure Manager, a.k.a. cshields), Mike Marineau (System Administrator at OSL), Matt Rae (Community Systems Administrator and drupal.org infrastructure manager at OSU, aka raema) had successfully moved the drupal.org database to the new server20, which made many people very happy.

_____________________

14 Internet Archive WayBack Machine, web.archive.org/web/web.php, www.drupal.org

15 Slashdot, “Drupal Needs a New Home,” developers.slashdot.org/article.pl?sid=05/07/10/1924256&tid=169&tid=8

16 Drupal, “The future Drupal server infrastructure,” drupal.org/node/26707

17 Tim Bray, “Iron for Drupal,” www.tbray.org/ongoing/When/200x/2005/07/14/Drupal-Server

18 Drupal, “The future Drupal server infrastructure,” drupal.org/node/26707

19 Tim Bray, “Iron for Drupal,” www.tbray.org/ongoing/When/200x/2005/07/14/Drupal-Server

20 Various. kveton.com/blog/2005/08/26/drupalorg-before-and-after/, drupal.org/node/29670

Figure 35-3. Drupal.org user expresses joy about new server speed

If You Have a Problem, Please Search Before Posting a Question

By 2006, Drupal was positioned to step into the role of major player in the world of Free and Open Source Software and the world of web site development at large. But physical infrastructure of the sort provided by OSL is not the only type of infrastructure necessary to make sure that an entity like Drupal is scalable enough to survive into adulthood, so to speak; the infrastructure of the community itself is just as crucial.

The next section will outline the formation of an important piece of that community infrastructure: the Drupal Association. The process was long, and plenty of other exciting activity was taking place in the Drupal community while the research and debate on what form the Association should take continued; however, a detailed look at how the Association came to be is informative on many levels. Not only does the framework established within the statutes and internal regulations of the Association charter define how Drupal is allowed to grow (and who is allowed to influence that growth), but peeking at the process that the community used to craft it can be revealing.

Just as the Drupal community had been discussing the need for new infrastructure months before the server crash made obtaining it an inescapable and immediate priority, discussion concerning the formation of some sort of not-for-profit entity capable of handling Drupal’s financial affairs had been bouncing around for a while.

Figure 35-4. (Facetious?) New Year’s Eve prediction for 2004, posted by then maintainer of drupal.org’s server, Kjartan Mannes

Speaking seriously, it was well understood that any structure that was established would have far-reaching consequences (economic, legal, and cultural) for the Drupal community and potentially for the software itself. As Steven Peck explained to an individual concerned by Drupal’s lack of an intensive fundraising initiative in a June 29, 2005 drupal.org forum reply, “Discussions are occurring. Stuff just takes time to do right.”21

Days after the server crash, Dries’ July 14, 2005 drupal.org announcement of the plan to disburse the entirety of the fundraising windfall to OSL galvanized another round of public debate on the foundation issue. Folks expressing their concerns that none of the US$10,000 had been used to set up some sort of a foundation were assured (with varying degrees of politeness) that:

- Money had indeed been located for the purpose of creating some sort of not-for-profit-entity, in the form of promised matching funds (to be delivered when needed).

- It was a deemed wise to hand all of the server donations over to a third party (which incidentally did, unlike Dries, hold not-for-profit status) that would spend the money on servers and hosting because that was what donors expected their money to be spent on, and issues of fiscal responsibility can become hazy when solicited donations are sitting in a private individual’s account, no matter how trustworthy and dedicated that private individual may be.

- Members of the Drupal community with very personal stakes in the matter had already been working on this complex issue, doing careful and extensive research, and would continue to work on it until a satisfactory solution could be reached.

In other words, funds were not the main issue. The undisclosed amounts promised by Advomatic, CivicSpaceLabs, Google, and Packt Publishing would be sufficient to cover costs; the main issue was the scope of the task. To proceed, the Drupal community had to come to some sort of internal consensus as to what it needed and wanted—and perhaps more importantly, did not need or want—from a foundation. As Chris Messina (factoryjoe) pointed out in his July 14, 2005 drupal.org comment “Regarding the Drupal Foundation,” in addition to “scoping out various legal service providers,” another priority was “looking into the vast open source community for ideas, opinions, and other helpful insights into how to do this right—there’s no sense in reinventing the wheel if we don’t have to!”22

DrupalCon Portland 2005 (a free conference from August 1-5 held alongside the O’Reilly Open Source Convention in Portland, Oregon) provided the venue for a roundtable discussion about needs, wants, and concerns regarding a Drupal Foundation. OSCON itself provided a venue for picking the brains of those involved in the formation of other FOSS Foundations. Boris Mann’s drupal.org News and Announcements post “DrupalCon Portland 2005: Drupal Foundation meeting” summarizes the takeaways from the meeting as follows:

“Some examples of needs include:

- Ability to accept and give out funds

- Hold assets (e.g., servers and other hardware)

- Bookkeeping to track funds and how they are spent

A selection of the group’s thoughts on goals for the Drupal foundation:

- Attract more users and developers

- Provide server infrastructure for related projects

- Manage Intellectual Property (trademarks, copyrights, licensing, etc.)

- Fund developer meet-ups”23

_____________________

21 Drupal, Comments on “Why does drupal.org choke so much?”, drupal.org/node/25982#comment-45105

22 Drupal, Comments on “Why does drupal.org choke so much?”, drupal.org/node/25982#comment-45105

Later in the post, Boris mentions that Dries identified an additional goal—the creation of a funded position to lift the substantial burden of maintaining the drupal.org web site off the shoulders of the volunteers (Dries, Steven Wittens, etc.) who spent approximately eight hours a week on such housekeeping tasks. Incidentally, the same post also details the input from a community member who felt that the formation of a foundation was not a necessary step:

“Kieran...had a more pragmatic view. The Drupal community has figured out how to get money, we’ve got a great ecosystem that can come up with solutions on the fly. With free hosting from OSL and a great set of server infrastructure, we’re fine as we are now.24

- Boris Mann

![]() Note Boris is referring to Kieran Lal, a.k.a. Amazon (

Note Boris is referring to Kieran Lal, a.k.a. Amazon (drupal.org/user/18703), the then Development Manager for CivicSpace who would go on to serve on the Drupal Association’s Board of Directors every year from its inception to the current day, first as Fundraiser and then as Director of Business Development.

Now we skip ahead almost a full year to June 25-30, 2006. While it may seem like a long time to let an issue sit, keep in mind that Drupal does not and has never stood still; the same people who were discussing options for a foundation also had day jobs to work, code to write, bugs to fix, and Cons to organize and attend (and, in Dries’ case at least, a fiancée to marry)25.

About a month and a half after the official release of Drupal 4.7, Dries announced on his blog buytaert.net his intent to continue his research into questions of community infrastructure by picking the brains of “some of the smartest people in the FOSS and Internet community.” The itinerary for Dries’ “Drupal road trip to San Francisco” included personal meetings with Tim O’Reilly (Founder and CEO of O’Reilly & Associates), Chris DiBona (Open Source Programs Manager at Google), Mitch Kapor (Co-Founder of Lotus-1-2-3, Founder of the Open Source Applications Foundation, Co-Founder of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, and Chair of the Mozilla Foundation), Jeffrey Veen (Co-Founder of Adaptive Path, Project Lead of Measure Map, and User Experience Leader at Google), Chanel Wheeler a.k.a. chanel (drupal.org/user/4733, Software Applications Developer at Yahoo!), Bradley Greenwood (Lead Software Engineer/Open Source Software Evangelist at Yahoo!), Janice Fraser (CEO of Adaptive Path), Guido van Rossum (Founder of the Python project and Google employee), Larry M. Augustin (Founder and CEO of VA Linux), Anders Tjernlund (Vice President of Support Services at SpikeSource), and Brian Behlendorf (Co-Founder of the Apache Foundation)26.

_____________________

23 Drupal, “DrupalCon Portland 2005: Drupal Foundation meeting,” drupal.org/node/28338

24 Drupal, “DrupalCon Portland 2005: Drupal Foundation meeting,” drupal.org/node/28338

25 Drupal, “Dries and Karlijn married,” drupal.org/node/55814

26 Various. http://buytaert.net/drupal-road-trip-san-francisco, www.adaptivepath.com/about, www.linkedin.com/in/jeffreyveen/, www.linkedin.com/in/chanelwheeler, younoodle.com/people/bradley_greenwood

These discussions provided the starting point for months of intensive research by Dries Buytaert, Dries Knapen, and Steven Wittens. None of these individuals had any previous expertise in the field of international tax law, but (in classic open source fashion) they spent hours soliciting input from those who did. By September 2006, they had produced a draft of the statutes and by-laws of what would become the Drupal Association.

But wait, aren’t we talking about a foundation? What’s this association?

As a result of their research, one of the decisions that Dries Buytaert, Dries Knapen, and Steven Wittens made was to incorporate the Association in Belgium, rather than in the United States. Belgian law differentiates between an Association and a Foundation, and according to the Drupal Association FAQ, the most significant differences between the two are:

- An Association is incorporated by several individuals, who agreed upon the goals of the Association after voting and discussion, whereas a Foundation can be incorporated by one person (or a small number of people)

- When incorporated, the founders must bring in initial assets (funds) in a Foundation. This is not the case for an Association

- An Association has members. A Foundation can’t have members, only a Board of Directors... In other words, an Association allows for a far more democratic operating mode than a Foundation....[and] therefore reflects the way a real (or online) community of people works to a much higher extent than a Foundation.27

After some review and revisions of the draft by members of a mailing list created for this purpose, Dries used the venue of DrupalCon Brussels 2006 to publicly announce what had been accomplished.28 Attendees of the session provided feedback, and the Association mailing list grew. In November, Dries Buytaert, Dries Knapen, and Steven Wittens selected the first round of Permanent Members from the individuals who had submitted their candidacies through this mailing list, which was the first step in establishing the membership of the Association.29 On December 7, 2006, The Drupal Association’s statutes were legally recognized by the Belgian courts,30 and on February 26, 2007, the formal announcement of the Association was posted on drupal.org and association.drupal.org.31

So what did those statutes contain? After years of discussion, months of research, weeks of intensive work, and a constant flow of input from the community, what did three tech-geeks with little to no experience writing legal documents manage to come up with?

In short, they managed to come up with a structure that ensured that control of Drupal would always be in the hands of those who work to create it, and that those same individuals would not have their time and energies diverted from improving the project to carrying the burden of administrative duties.

As the Association is very careful to make clear, “The Drupal Association has no say in either the planning or development of the Drupal open source project itself. The Drupal Association could, however, do any of the following:

_____________________

27 Drupal, FAQ, association.drupal.org/about/faq

28 Google video, DrupalCon, 2006. video.google.com/videoplay?docid=7038940559530825104

29 Drupal, FAQ, association.drupal.org/about/faq

30 Drupal, “Announcing: The Drupal Association,” association.drupal.org/node/71

31 Drupal, various announcements, drupal.org/node/122835, association.drupal.org/node/71, association.drupal.org/node/87

- Accept donations and grants.

- Organize and/or sponsor Drupal events, and represent the Drupal project at events.

- Engage in partnerships with other organizations.

- Acquire and manage infrastructure in support of the Drupal project.

- Support development by awarding grants or paying wages.

- Write and publish press releases and promotional materials.”32

The body of members who vote on these issues (Permanent Members, who together make up the General Assembly) are differentiated from the body of members who pay dues in support of the Association (Admitted Members), ensuring that an inability to afford membership dues does not make one ineligible to take part in the decision-making process.

The statutes and bylaws also clearly define and restrict the role that corporations, companies, and other “legal persons” are allowed to play in the Association. While corporations and companies may purchase memberships and so become Admitted Members, they are explicitly barred from having voting rights in the Association’s decision-making body, the General Assembly. If, however, they have the recommendation of a member of the General Assembly, a corporation or other legal person can become an Advisory Member. While Advisory Members aren’t allowed to vote, they are allowed to attend meetings of the General Assembly and...well...advise.33

This setup allows business entities in the community to stay informed of the issues being discussed by the Association, and for the voting members of General Assembly to receive informed input from those business entities, without the possibility of a commercial interest controlling the award of Association contracts, grants, or wages. Additionally, the Board of Directors is given the right to deny admission to any entity applying for Admitted Membership “if in the judgment of the Board of Directors there is evidence that the actions, ideas/views/beliefs, and/or motivation of the new member applicant are adverse to the Association’s interests,”34 and at any time, “an Admitted Member can have his/her membership terminated by simple resolution of the Board of Directors.”35

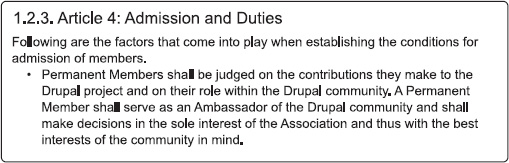

For Permanent Members, the process of admission (and termination) is more democratically arranged. To become a Permanent Member, an individual must be recommended by someone who is already a Permanent Member. Once the individual has their recommendation, they then send an application to the President of the Board. The General Assembly votes on whether or not to admit the applicant; if two-thirds of the Assembly agree, the individual is accepted as a Permanent Member. As the name suggests, there are no terms for Permanent Members (“Permanent membership has an unlimited duration.”) but Permanent membership can be revoked by a two-thirds majority vote of the General Assembly.36

_____________________

32 Drupal, About page, association.drupal.org/about/introduction

33 Drupal Association Statutes, 1.3.1 Article 10, association.drupal.org/system/files/statutes-en.pdf

34 Drupal Association Internal regulations 1.2.3 Article 4, association.drupal.org/system/files/internal-regulations-en.pdf

35 Drupal Association Statutes 1.2.4 Article 8, Section 3, association.drupal.org/system/files/statutes-en.pdf

36 Drupal Association Statutes 1.2.3, Article 7, Section 3 & Section 2 association.drupal.org/system/files/statutes-en.pdf

Figure 35-5. Drupal Association Internal Regulations ![]() Membership

Membership ![]() Admission and Duties

Admission and Duties

The General Assembly also votes (by open ballot) on which of their number gets elected to the Board of Directors. Any Permanent Member seeking a position on the Board must submit an application to the President listing their motivations and proposed contributions. If the candidate receives approval in a two-thirds majority vote of the General Assembly, they are then officially a Director, though it is the rest of the Board—not the General Assembly—that votes to determine which Director fills which office. In other words, the Assembly cannot vote a President into office, but only someone that the Assembly has approved has a chance of becoming President of the Association.37

The Story Continues

As stated at the beginning, the history of Drupal is much more than covered here. Among other things it includes the commercial growth of Drupal, the evolution of Drupal as enterprise-level software, and the development of Drupal 7 implicit in this book. Drupal is an absurdly chaotic system that produces bizarrely functional results...just like nature. Yet it is not completely random; the events recounted in this chapter suggest that key actions affecting Drupal's ecosystem have helped the success the Drupal community has enjoyed. Moreover, it is evident that this growing software project remains open to having the course and breadth of its history altered—perhaps by another typo or server crash, perhaps by you.

![]() Note Discussion, updates, and related material for this chapter can be found at

Note Discussion, updates, and related material for this chapter can be found at dgd7.org/history.

_____________________