1

The Wide World of Possibilities

THE BUYERS ARE WAITING

You’ve probably turned to a photograph in a book or magazine and said, “I can take a better picture than that.” You’re probably right . . . and not only from the point of view of quality or subject matter. Often a photo you see published in a magazine or book doesn’t really belong there. When the deadline arrived, the photo editor used it because it was there and available, not because it was the perfect, or the best possible, photograph.

Photo buyers would gladly use your photographs if they knew you existed and if you’d supply them with the pictures they need, when they need them. The buyers literally are waiting for you, and there are thousands of them. This book will show you how to locate the markets that are, at this very moment, looking to buy pictures from someone like you, with your special know-how and your camera talent. This book also will show you a no-risk method for determining what photo editors need; how you can avoid wasting shoe leather, postage, e-mail and website visits; plus how you can avoid markets that don’t offer any future for your kind of photography. You’ll earn the price of this book in one week through the time, stationery, postage and phone bills it will save you.

If you’re a newcomer to the field of photomarketing, you’ll be surprised to learn you can start at the top. I know many who have done so; I did so myself. Many of my pictures have sold to Mc-Graw Hill, BBC, The Guardian, Le Monde, the New York Times, Pearson, Scholastic and the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, just to mention a few examples. That said, I soon discovered that if I wanted to sell consistently to the top magazines, I would have to travel continually and make my headquarters in a place that was a good deal larger than Wilber, Nebraska. That was not what I wanted. I wanted to make a life for me and my wife in a smaller community. Besides, before I moved to the United States I traveled all over the world 300+ days a year and traveling wasn’t something I really wanted to do, so I started researching other possibilities.

I found there were at least 10,000 picture markets out there (many more exist today). I figured if I subtracted the top-paying newsstand magazines, numbering about 100, that left 9,900 for me to explore, and to find several hundred that emphasized subject areas I liked to photograph. I learned that most of these markets were as close as my computer and that many of them actually were eager for my photographs. Most important, I could sell to these markets on my own timetable and live wherever I wanted.

Trends in the Marketplace

In 1990 when I began marketing my pictures, few persons had the title “photo editor.” The art director or an editor at a publishing house doubled as the person who selected pictures. The picture-selection process often was done at the last moment, whenever the book or magazine text was finalized. In those days photos frequently served simply to fill white space or to support a subject with illustrative documentation.

During recent decades our society has become increasingly visually oriented to the point of a veritable explosion in the use of visuals. People today are more prone to be viewers than they are to be readers. Reading material is more and more capsulized. Witness the proliferation of condensed and “instant” books and specialized newsletters, the success of USA Today and its influence on the formats of many other newspapers, and magazines like Time and Newsweek designing their editorials as chunks of summarized information. People rely less on the printed word and more on pictorial images for entertainment and instruction. An automatic coffeemaker gives its instructions in illustrations rather than text. Point-of-sale terminals at most restaurants provide clerks with pictures rather than words. Textbooks have more pictures and larger type. Illustrated seminars, websites and instructional CD and video presentations are the preferred tools for education throughout the industry, and TV is conditioning all of us to visuals every day.

Words and printed messages aren’t going out of style, but a look in any direction today shows us that photography is one of the most prominent means of interpreting and disseminating information.

New positions have been created in publishing houses—photo editor, photo researcher, photo acquisition director—positions that never existed in the past. Revolutionary technology is developing to handle and reproduce pictures. Publishers produce millions of dollars’ worth of books, periodicals and audiovisual materials every year. The photographs used in these products often make the difference between a successful venture and a failure. An editor isn’t kidding when he or she says, “I need your picture.”

The breadth of the marketplace may come as a surprise. For example, some publishing houses spend as much as $10,000–80,000 a month on photography. Some of these thousands could regularly be yours if you learn sound methods for marketing your pictures.

As I mentioned earlier, you can start at the top. It’s not impossible, but making a full-time habit of selling to the top markets requires a specific lifestyle and work style. You need to examine your total goal plan and make some major decisions before you launch after the biggies. Only a handful of people break into that small group of professionals who enjoy regular assignments from the top markets. Moreover, most of those professionals pay their dues for years before they get to where their phones ring regularly.

Too often, the newcomer to any field believes the top is the only place it’s at. The actor or the musician rushes to Hollywood to make it big. We all know how the story usually ends. Out of thousands only a few are chosen. We also know that they’re not chosen on the basis of talent alone. Being at the right place at the right time is usually the key. The parallel holds true in photography. Good photographers are everywhere—just check the yellow pages and the Web. As with actors and musicians (or artists, dancers, writers and so on), talent is only one of the prerequisites. Having what is needed when it is needed is typically more important than how good a photograph is, provided your digital photos meet the technical specifications. More on this later.

However, if you’re serious about your photography and are willing to look beyond the top, you’ll discover a wide world of possibilities. There are markets and markets—and yet more markets. You will get your pictures published consistently, with excellent monetary return, and with the inner satisfaction that comes from putting your pictures out where others can enjoy them. You can accomplish this if you apply the principles I outline in this book. Your pictures will be at the right place at the right time, and your name will be on the checks sent regularly by the photo buyers and editors that you identify as your target markets.

Fifty Thousand Photographs a Day

As you read this, at least fifty thousand photographs are being bought per day for publication worldwide at fees of $25–100 for black and white, and often twice as much for color. I’m not talking about ad agencies or general newsstand-circulation magazines. These are closed markets already tied up by staff photographers or established professionals.

I’m referring to the little-known wide-open markets that produce books, magazines, CD-ROMS, websites and related printed products. Such publishing houses have proliferated all over the country in the last three decades. Opportunities for selling photographs to the expanding stock photo industry have never been greater. Some publishing companies are located in small towns, but that’s no indicator of their photography budgets, which can range, I repeat, from $10,000–80,000 or higher per month.

A WIDE-OPEN DOOR

These publishers constantly need photographs. Many publishing companies produce three dozen different magazines or periodicals, plus related publications such as bulletins, books, curriculum materials, CD-ROM and DVD materials, brochures, video series and reports. Staffs of the larger publishing houses have scores of projects in the works at one time, all of which need photographs. Before any company completes a publishing project, it’s searching for photographs for the next project.

Textbook publishers fiercely compete with each other to nail down contracts with colleges and universities, technical institutes, school boards and educational associations to produce millions of dollars of photo-illustrated educational materials. These materials range from printed manuals to CD-ROM and DVD discs.

Regional and special-interest magazines number in the thousands. While many general-interest magazines have been struggling or folding, regional and special-interest magazines (open markets for the stock photographer) have been on the rise. With the enormous amount of information available in any field or on any subject in today’s world, our culture has become one of specialization. Increasingly, magazines and books reflect this emphasis, focusing on self-education and specific areas of interest, whether business, the professions, recreation, entertainment or leisure. This translates into still more markets for the stock photographer.

Another major marketplace is found in the scores of denominational publishing houses that produce hundreds of magazines, books, periodicals, curriculum materials, posters, bulletins, video programs, CD-ROMs and interactive media. Some of these companies employ twenty or more editors who seek photos for all their publishing projects. Most of these photos focus on “the human condition” and are not what you might think of as specifically “religious.” The companies’ photography budgets are high because their sales volumes are high. Many have a photography budget of $25,000 per month.

As I mentioned earlier, nearly ten thousand markets are open to the stock photographer today. (That’s apart from the about one hundred top magazines such as National Geographic and Sports Illustrated.) These ten thousand open markets are accessible to both the part-timer and the full- timer. Photo buyers in these markets continually revise, update and put together new layouts, new issues, new editions, new publication projects, and new or updated CD-ROMs and websites.

If you compare the per-picture rate (modest) paid by these markets against that paid by the one hundred top magazines, or against what an advertising photographer receives for commercial use of his photo ($500 on average), there’s a big difference. But that’s misleading. Unless you number yourself among the handful of well-known veteran service photographers who sell to the top magazines (many have staff photographers in any case), gunning for those markets is sweepstakes marketing—chances are you won’t win. The same goes for top commercial assignments. When you score, it’s for a healthy dollar, but how frequently can you count on it? In addition, commercial accounts sometimes require all rights including electronic rights to your photos, or they may ask you to sign a work-for-hire agreement. (Read more about work for hire in chapter fifteen on page 261.)

In contrast, as a stock photographer “renting” or “licensing” your photos for editorial use (“sold” on a “one-time use” basis), you can circulate hundreds of pictures to publishing houses for consideration, each picture making from $25–200 at every sale. You don’t have to worry about the travel and deadline requirements of top magazine assignments or the stress of commercial assignments. Plus you can sell the same pictures over and over again.

You can do this from your own home, wherever you live. For the past thirty years, I’ve operated successfully out of a one-hundred-acre farm in rural Wisconsin. I can attest that more and more photographers are doing the same thing, from such diverse headquarters as a quiet side street in Kansas City, an A-frame in Boulder or an apartment in Santa Rosa.

When you master the photomarketing system outlined in this book, you’ll know how to select your markets from the vast numbers of possibilities and then tap them for consistent, dependable sales. If you’re like most of us, you’ll find that your range of markets includes some that are good starting points (easy to break into but pay modestly); some that are good showcases for your work (prestigious publications in your special-interest area that may pay little but offer a good name to include in your list of credits or good visibility to other photo buyers); many that will be regular customers for modest but steady return; and many that will be regular, well-paying customers.

Find the Market, Then Create

Many successful photographers say their careers surged when they realized that they were conducting the business side of their endeavors exactly backward. They had been creating first, then trying to find markets for the photos they created. That system can work to a certain extent (everyone gets lucky now and then), but it doesn’t make for consistent, predictable sales. It’s another form of sweepstakes marketing. The secret to guaranteed sales: Find the market first.

This isn’t to say that you pick just any market and create for it. I mean search out the markets that appeal to you as a person and a photographer— markets that use the kinds of photographs that you like to take, markets you would love to deal with and create for, markets that wild horses couldn’t pull you away from.

Finding your corner of the marketplace is going to be like prospecting (see chapter three for more details). It’s going to take some digging, but the nuggets you discover will be worth the effort.

You, the Photo Illustrator

After you become familiar with the photomarketing system described in this book, you’ll find that you can wear two hats in photography: One hat is that of the photo illustrator or editorial stock photographer; the other is the hat of the service photographer. What’s the difference?

Service photographers market their services on schedules that meet the time requirements of their clients: ad agencies, businesses, fashion and food assignments, wedding parties, portrait clients, public relations firms and audiovisual accounts. Service photographers usually find that they need several different kinds of cameras, lenses, lights and accessories, photo imaging and manipulation software, scanners and frequently a well-equipped studio.

Stock photographers make and market their stock photographs (photo illustrations) on their own timetable, selling almost exclusively to publishers of books, magazines and related digital media. They deliver their photos primarily through the U.S. mail, United Parcel Service (UPS), Federal Express (FedEx) or other overnight couriers, and electronically. They can operate with one camera and three lenses, though they’re better off with two cameras. The extensive equipment and studio space (and resulting high overhead) of the service photographer aren’t necessary.

A photographer can be either a service photographer or a stock photographer or both. The marketing system in this book, however, addresses the stock photographer. As the demand for photo illustrations in the publishing world has increased, so have photography publishing budgets and the need for editorial stock photographers who can supply on-target photo illustrations to these specialized publishing houses.

THE “THEME” MARKETS

The primary markets for photo illustration are the publishing companies located in every area of the country, and the magazines, books and electronic media they produce. I’ve already touched on some major categories— educational, regional, special interest and denominational. Now we’ll look at each market in detail. Publishing houses specialize, and so should you. If you come across a magazine in one of your fields of interest, you’ll often discover that the magazine’s publishing house produces several additional magazines, usually related and focusing on the same theme or subject area. If your photomarketing strengths include that theme, you’ve discovered one of your top markets.

Prime Markets

- Magazines

- Books

Secondary Markets

- Digital media

- Stock photo agencies

- Decor photography outlets

Third-Choice Markets

- Paper product companies (calendars, greeting cards, posters, postcards, personalized photo products and so on)

- Commercial accounts (ad agencies, public relations firms, record companies, audiovisual houses, desktop publishers, Web designers, graphic design studios and so on)

- Newspapers, government agencies and art photography sales

You’ll find a full discussion of third-choice and secondary markets later in this book, so I’ll say just a word about them here. The third-choice markets range in marketing potential from “possible” to “not possible” for the stock photographer.

The secondary markets—digital media, sales through stock photo agencies and channels for decor photography—are discussed in detail in chapter twelve. Stock agencies aren’t markets in the usual sense; they’re middlemen who can market your photo illustrations for you. Decor photography (also called photo decor, wall decor, or fine art photography) involves selling large photos (from 16" × 20" [41cm–51cm] to wall-size) that can be used as wall art in homes, businesses and public buildings.

Both the agency and decor areas offer sales opportunities to the stock photographer and can be important to your operation, but just how important may be different from what you initially assume. Photo agency sales can be successful when you place the right categories of pictures with the right agencies (not necessarily the most prestigious). This takes some homework. Likewise, the decor route has its assets and its liabilities. Chapter twelve gives you the know-how to approach agencies and decor photography with a chance for elation rather than frustration.

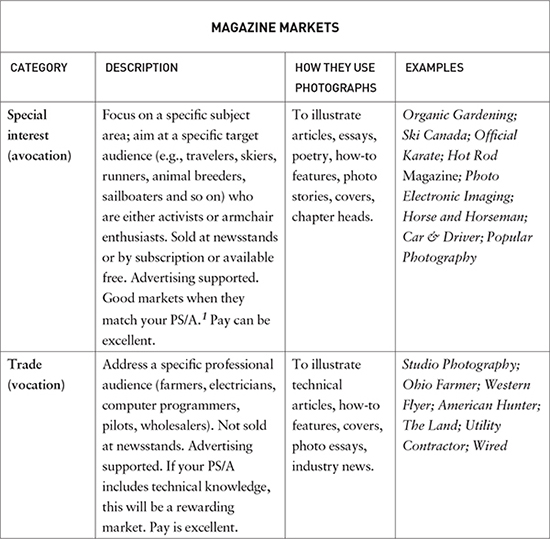

Now to the prime markets for the stock photographer: magazines and books (see Tables 1-1 and 1-2).

Magazines

You can determine how large a magazine’s photo budget is by asking this question: “Whose dollars support the magazine?” If the magazine runs on advertising support, the photography budget usually is high. If a company underwrites a trade or industry, the photography budget also usually is high. The photo budget is in the middle range if an organization or association supports the magazine or if subscriptions alone support it. Many magazines operate with a combination of advertising and subscription revenue, making for healthy photo budgets. Magazines with no advertising, subscription or industry/association support will have low photography budgets. In chapter three, I’ll show you how to be selective in choosing your magazine markets.

View a text version of this table

Budget, of course, should not be the sole factor you use in determining what markets to work with. Often it’s actually easier to sell ten pictures at $75 each to a medium-budget publication than it is to sell one picture at $750 to one of the higher-paying magazines. You can use the budget question to good advantage, though, in determining how healthy a magazine is and how stable a market it might be for you. Chapter eight will show you how to determine a market’s photo budget and the prices you should ask for your photos.

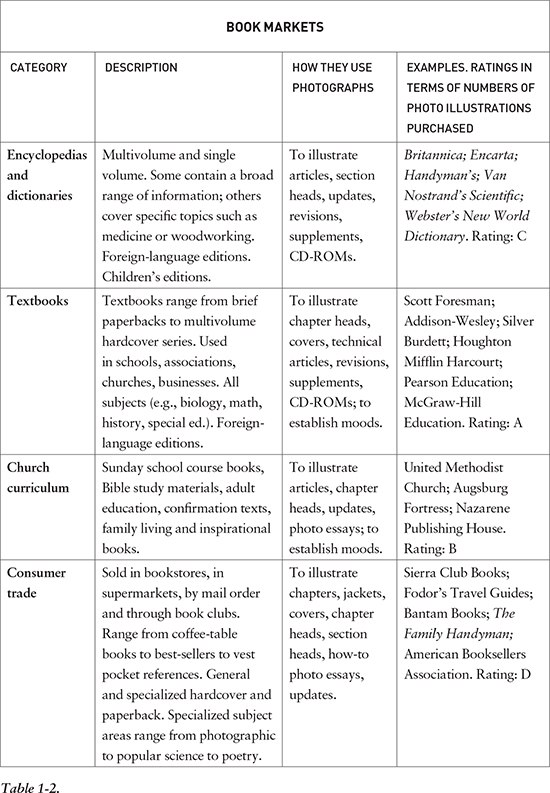

View a text version of this table

Books

Approximately three hundred thousand books are published in this country every year. Publishers, who orchestrate the complete package, produce books: They assign manuscripts, create graphics, edit, print, promote and distribute. Before you deal with a book publisher, get the answers to these questions:

- How well known is the publishing company?

- How long have they been in business?

- How wide is the market appeal of the book in question?

The photography budget usually is high if the book has a broad potential audience and the publishing company is well established. Fledgling book publishers, small presses and limited-audience publishers rarely pay high fees. Again, however, this is primarily to orient yourself—I’m not suggesting that your targets be only the high-paying markets. Selling a small publisher or a CD-ROM producer one hundred pictures at a bulk rate of $25 each for one-time use makes good sense. In chapter three I’ll show you how to find your target book markets; chapters seven and eleven will tell you more about sales to book publishers.

A Hedge Against a Downturn in the Economy

When there’s a downturn in the economy, photo editors turn to stock photography rather than hiring photographers to go on assignment. In the forty years I’ve been in stock photography, a recession (there have been five of them, so far) has always boosted my sales. Once the recession is over, some of those photo editors stay with me, having learned the economic advantages of buying direct stock from individual photographers. As stock agent Craig Aurness said in his International Stock Photography Report, “Stock is perceived as a recession-resistant industry, as downward trends force companies to look for alternatives to expensive assignment photography.”

Good Pictures—Wrong Buyers

The prime markets pay stock photographers millions of dollars a year to get the photos they need. Sounds promising for the photographer, but wait—the key word is need. Whether you plan on grossing $50 or $50,000 in sales each year with your photography, don’t ever forget that photo editors purchase only pictures they need, not pictures they like. If you supply the right pictures to them, they’ll buy. I’ve heard dozens of photographers over the years complain that their pictures weren’t selling. When I examined their selling techniques, it was easy to see why: They were putting excellent photographs in front of the wrong buyers. A photo buyer may think your pictures are beautiful, but she won’t purchase them unless they fit the publication’s specific needs. A photo editor is like any other consumer: If she needs it, she’ll buy it. Chapters two and three will show you how to determine what a photo buyer’s needs are and how to fill them.