Chapter 8

Setting

“My books begin with a place, the feeling I want to set a book there, whether it’s an empty stretch of beach or a community of people.”

—P.D. James in an interview with Salon.com

It’s been said that a vivid setting is like another main character in the novel, and sometimes it is. At the very least, your setting has to be credible and fit your story’s plot, characters, theme, and emotional tone.

Setting includes these dimensions:

- When: year and season

- Where: geographic locale, exteriors, and interiors

- Context: activities and institutions that provide the primary backdrop

I began writing There Was an Old Woman with a mental image of Mina Yetner, a ninety-one-year-old woman sitting on her back porch, gazing across a salt marsh, over an expanse of water to the Manhattan skyline. So I set her house in the Bronx, where there really is a community with modest old houses that fit the bill. When Mina was little she lived there and watched the great skyscrapers go up. I learned about a B-25 bomber that crashed into the seventy-ninth floor of the Empire State Building on a fogbound morning in 1945, so I decided that Mina’s first job had been working in the Empire State Building. She was one of the few remaining survivors of a fire that followed the crash. Those details of time and place worked perfectly with my story.

Pick your settings carefully, because whatever you choose both constrains and enriches your story’s possibilities. Before you start writing, make a list of possible whens and wheres for potential scenes. Then research and explore the dramatic possibilities. If you can, pay a visit to each place. Take pictures and take notes. If you can’t visit, then find photographs and written descriptions and talk to people who’ve been there. When it’s time to write, you’ll be able to use real details and add plausible fictional touches.

WHEN: THE YEAR

When your novel takes place—in the present, the past, the future, or even a made-up time in a fantasy universe—has a major impact on all aspects of the book. It affects what characters wear, what they worry about, what their homes are like, how they get around, the products they use, the music they listen to, and so on. It also constrains the kind of crime investigation that can take place. Laurie R. King’s protagonist, Mary Russell, apprentice and then wife to Sherlock Holmes in early-twentieth-century London, relies on old-fashioned observation and deduction. Kinsey Millhone is in a 1980s time warp, so Sue Grafton never has to work her plots around cell phones or DNA evidence. Kathy Reichs sets her Temperance Brennan series in the present, so she has all the trappings of modern forensic science at her disposal. Give the investigators in your novel the tools appropriate to their time period.

Setting your story in a particular historical time frame allows you to intertwine your story with concurrent events. The Great Depression, the Roaring Twenties, World War II—virtually any time period can provide a rich historical context with real individuals and events you can use as part of your story.

Set your story in the present and you can include current events. The downside is that current events can quickly make your story seem dated. Remember, even for writers with a contract in hand for their new book, it often takes two years from the time they begin writing until the book is published. What seems like a major news story when you’re writing your novel may be a big yawn a year later. So only include current events that matter to your story.

Some events might feel too big to be left out of any story set in the fictional present. I was in the middle of writing a novel set in the present when 9⁄11 terrorist attacks took place. My paranoid villain would have been profoundly affected by the news. I considered putting the event into the book, but decided not to. I was convinced that readers weren’t ready to read about those events in a crime novel meant to entertain. Moreover, I wasn’t emotionally equipped to write about it.

Make a conscious, reasoned decision on whether to include concurrent events in your novel. Weigh the pros and cons, the advantages and limitations, and most of all trust your instincts.

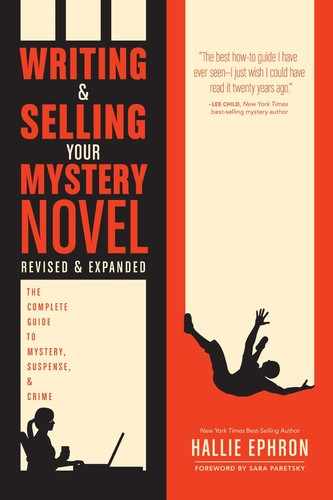

Now You Try: Including Concurrent Events (Worksheet 8.1)

Make a list of the events that are concurrent with your novel’s time frame. List reasons in favor of including or excluding those events.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

WHEN: THE SEASON

You can exploit the season in which your story takes place in several ways. Extreme weather—hurricanes, monsoons, blizzards—can create a dramatic backdrop. In this example from Raymond Chandler’s short story “Red Wind,” a description of Southern California Santa Ana winds provides a powerful way to open the first scene:

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot, dry, Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that, every booze party ends in a fight. Meek, little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands' necks. Anything can happen.

The Santa Anas most often arise in the fall and winter.

The season—or seasons, if your novel’s time frame is long enough—you pick creates multiple story possibilities. In winter, an ice storm in Vermont can shut down roads and delay a medical examiner trying to reach a crime scene. A summer heat wave in Kansas City can leave elderly shut-ins dead, one of whom turns out to have been murdered. Soaking spring rains can turn roads to mud, send hillsides sliding into houses, and leave your protagonist stranded by the side of the road and chilled to the bone.

Be aware of the nuisance factor in the season you pick. Set your story in a New England winter and your characters will be forced to bundle up and de-ice their car windshields whenever they go out. If you want your character to take a pleasant stroll and come across a body washed up at the edge of a creek, make sure that the weather would be warm enough at that time of year for strolling and that creeks wouldn’t be dried to a trickle. You can’t have a character skulking about in pools of darkness between the streetlights at eight o’clock on a July evening—the sun wouldn’t have set.

Whatever time period and season you choose to set your story, spend some time planning how you’ll put those choices to work in your story.

Now You Try: Making the Most of “When” (Worksheet 8.2)

Write down the year(s) and season(s) you’ve chosen to set your novel. Brainstorm a list of how your choices can affect your story in terms of investigational techniques, concurrent events, weather, and so on.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

WHERE: GEOGRAPHIC LOCALE

The geographic locale where you set your novel provides you with a range of possible dramatic landscapes in which to bring your story to life. A small town presents as many possibilities as a big city. The quiet Kentish village of St. Mary Meade serves as the perfect backdrop for Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple series. Venice, with its mist-shrouded canals and palazzos, makes a rich backdrop for Donna Leon’s Commissario Guido Brunetti novels.

Readers love local color, and the audience for most mystery series grows from its geographic location. On the other hand, exotic locations entice readers who yearn for the unknown. What matters is that you know your setting, bring it to life on the page, and take advantage of the opportunities your setting presents.

Let the geographic locale shape your characters’ behavior. New Yorkers avoid eye contact with strangers, while Texans say “howdy” to everyone. A Milwaukee police officer might have a passion for bratwurst; one of Chicago’s finest might be an aficionado of Red Hots.

Here are some ways your characters might reflect the geographic locale you pick:

- how they talk—word choice, speech patterns, and dialect

- what they wear

- what they eat and drink

- how they get places

- how they treat strangers

- what sports teams they root for

Here’s an example from Laura Lippman’s The Sugar House. Through the details Lippman chooses, she makes Baltimore come alive.

Sour beef day dawned clear and mild in Baltimore.

Other cities have their spaghetti dinners and potluck at the local parish, bull roasts and barbecues, bake sales and fish fries. Baltimore had all those things, too, and more. But in the waning, decadent days of autumn, there came a time when sour beef was the only thing to eat, and Locust Point was the only place to eat it.

Like so many mystery writers, Lippman writes about her series setting so vividly because she lives there. If you set your novel where you’ve lived, you can use your insider’s knowledge. If you set your story somewhere you’ve never lived, leave yourself time during the planning stages to visit and research the locale thoroughly.

WHERE: EXTERIORS

Once you’ve picked your geographic locale, think about the exteriors you can use to set scenes. If you’re using real exteriors, make them as accurate as possible. Readers don’t like it when your character drives the wrong way up a one-way street or when a well-known restaurant is unwittingly relocated to a new neighborhood.

You can finesse the details by creating a fictional neighborhood that echoes the features of a real one. Dennis Lehane set Mystic River in a fictitious blue-collar Boston neighborhood he called “East Buckingham,” but its details will ring true to anyone familiar with the Boston suburbs of Charlestown, Southie, Brighton, or Dorchester (where Lehane grew up).

They all lived in East Buckingham, just west of downtown, a neighborhood of cramped corner stores, small playgrounds, and butcher shops where meat, still pink with blood, hung in the windows. The bars had Irish names and Dodge Darts by the curbs. Women wore handkerchiefs tied off at the backs of their skulls and carried mock leather snap purses for their cigarettes.

A few pages later, Lehane sets a scene in another semifictional locale he calls the Flats:

Jimmy looked at the Flats spread out before him as he and the old man walked under the deep shade of the tracks and neared the place were Crescent bottomed out and the freight trains rumbled past the old, ratty drive-in and the Penitentiary Channel beyond, and he knew—deep, deep in his chest—that they'd never see Dave Boyle again.

Made-up exteriors like East Buckingham and the Flats work fine as long as the details are vivid and ring true. An adobe hacienda in the middle of Boston won’t wash, nor will cobblestone streets in Los Angeles. Some writers draw maps of the exteriors they invent to keep themselves oriented and their story consistent.

WHERE: INTERIORS

Your novel may have as many as a dozen interior settings. One recurring interior will probably be your protagonist’s home.

Here are two kitchens described in my novel There Was an Old Woman. My goal was not only to create vivid interiors but to show the reader the contrast between the two women who inhabit these spaces.

Evie’s mother’s kitchen:

Evie turned instead and entered the kitchen. She threaded her way around piles of newspapers and loaded paper bags and plastic garbage bags. The sink was overflowing with dishes, and the faucet was dripping. Evie reached over and turned it off. Pushed open the red-and-white gingham curtains that were gray and crusty with dust, and opened the windows. On the sill, a row of African violets were brown and withered.

Evie’s neighbor’s kitchen:

Now Evie looked around in awe at the spotless kitchen with its black-and-white checkerboard tiled floor, two-basin porcelain-over-cast-iron sink standing on legs, and a pair of pale-green metal base cabinets with a matching rolltop bread box sitting on a white enamel countertop. Spatulas and spoons hung from hooks on the wall, all with wooden handles painted that same green. The utensils had the patina of old tools, used for so long that they bore the imprint of their owner’s hand. Evie felt as if she'd stepped into a 1920s time warp.

Each time you bring an interior setting to the page, decide what you want to show the reader about the character who inhabits that space. If your character is anal and methodical, you might choose steel-and-glass furniture and a Mondrian print on the wall. If your character is absentminded and careless, his desk might be adrift in paperwork and the rug frayed at the edges. If your character is cheerful and optimistic, her home would probably be freshly painted and filled with bright colors. If he’s morose and brooding, maybe the windows are shrouded with dusty, green velvet drapes.

In your mind, transport yourself to your character’s home. Is it a mansion, apartment, mountaintop cabin, or homeless shelter? Is it filled with fine antiques, battered items salvaged from yard sales and thrift stores, minimalist designer furniture, or unopened storage boxes? Is there a big-screen TV or a vintage radio? Does the kitchen have all the latest gadgets or just a microwave for reheating takeout? Each choice should be a reflection of your character’s personality and where he is at this juncture in life.

Other interiors relate to your protagonist’s job. If your protagonist is an attorney, you’ll probably write scenes that take place in a jail and a courtroom. If your protagonist is a medical examiner, you’ll need an autopsy room and a morgue. Most novels featuring a homicide detective have scenes that take place in squad cars and police stations.

Have at the ready some interiors where your protagonist goes to relax. Sue Grafton’s Kinsey Millhone often finds refuge at a dingy local tavern serving Hungarian food cooked up by Rosie, a colorful recurring character.

It’s fun to use real interiors to set scenes. Local readers enjoy finding places they recognize. A good rule of thumb is: It’s okay to use a real place if nothing terrible happens there. If your characters are meeting for a relaxing meal, you can use a real restaurant; if your character is going to get food poisoning after eating there, you should use a made-up place. You don’t want to make enemies out of restaurant owners, and you certainly don’t want to get sued.

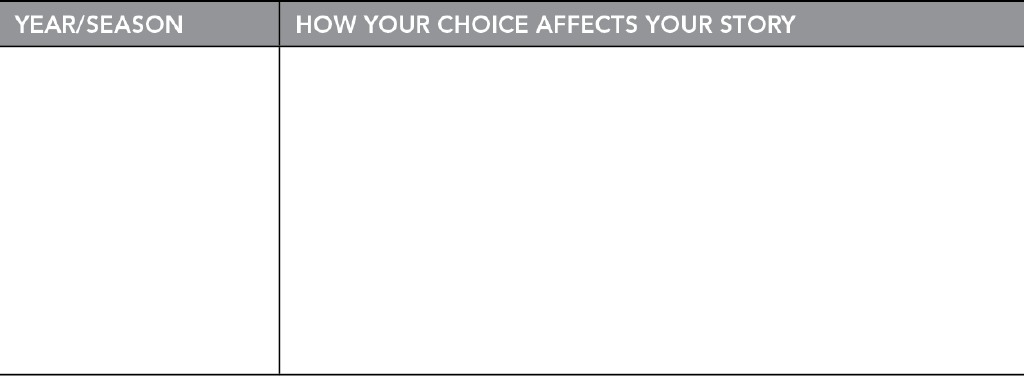

Now You Try: Making the Most of “Where” (Worksheet 8.3)

Pick a geographic location and list all the interior and exterior settings where you’ve chosen to set your novel. List the aspects of setting that you’ll be able to use to your advantage in the story.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

CONTEXT: ACTIVITIES AND INSTITUTIONS

The activities and institutions that provide the backdrop to your story are another dimension of setting. Most mysteries have the context in which the sleuth operates, plus the context in which the crime occurred. For example, the most common context for a mystery is law enforcement—the main characters are police detectives; the activities are basic interrogation and investigation; and the institutions are those that make up the criminal justice system, from police departments to jails to courtrooms. Still, each police procedural has an added context: the backdrop for the crime. For example, if the police are investigating art theft, their investigations might take them into artists’ studios, art museums, galleries, or auction houses. If you’re writing an amateur sleuth, the backdrop becomes your sleuth’s day job and the world your sleuth inhabits.

The backdrop you pick for your book is an important factor in marketing your novel. A mystery set in a medical examiner’s office featuring graphic autopsies is going to repel the more squeamish reader. A mystery set at a bird sanctuary featuring a birder who witnesses a crime while tracking down a red-footed falcon probably won’t appeal to readers who like their mysteries fast paced and hard-boiled.

Here are some examples of backdrops that have been used in mystery novels:

| Activities | Institutions |

|---|---|

Art collecting | Museums, auction houses, art galleries |

Medical research | Hospitals, universities, private labs |

Gambling | Race tracks, casinos |

Smuggling endangered species | U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, U.S. Customs |

Drug dealing | Organized crime, street gangs |

Golfing | The PGA tour, country clubs, golf courses |

Pick a backdrop you know intimately or one that interests you enough so you won’t mind doing the research necessary to make it come alive.

Here are some of the aspects of backdrop to research in advance:

- Costume: the formal or informal dress codes that determine what people wear; how clothing indicates status

- Jargon: the special terms and expressions that are widely used

- Equipment: special equipment and tools, and how they operate; safety precautions

- Pecking order: the high- and low-status jobs, and how people at various levels recognize and treat one another

- Schedule: the events that happen in a typical day or night, week, or month

- Behavior: the written and unwritten codes that influence how people behave in typical and extreme situations; what boundaries they’re not supposed to cross

Now You Try: Making the Most of the Backdrop (Worksheet 8.4)

Write down the institutions and activities that provide a backdrop for your mystery novel. Make a list of the questions you need to answer in order to write a convincing backdrop.

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

PERSONAL SPACES THAT REVEAL CHARACTER

The details of a character’s personal spaces—his office, car, kitchen, bedroom—offer you rich opportunities to demonstrate the character’s personality and quirks. Here’s Stephanie Plum looking in her refrigerator in Janet Evanovich’s first series novel, One for the Money. The details are pungent and priceless.

… I shuffled into the kitchen and stood in front of the refrigerator, hoping the refrigerator fairies had visited during the night. I opened the door and stared at the empty shelves, noting that food hadn’t magically cloned itself from the smudges in the butter keeper and the shriveled flotsam at the bottom of the crisper. Half a jar of mayo, a bottle of beer, whole-wheat bread covered with blue mold, a head of iceberg lettuce, shrink-wrapped in brown slime and plastic, and a box of hamster nuggets stood between me and starvation. I wondered if nine in the morning was too early to drink beer.

Open a character’s refrigerator for the reader and you might find:

- six-packs of vitamin water

- stacked matching plastic containers of leftovers, each labeled with the contents and date

- so much food that the milk leaps out at whoever opens the door

- medications

- nothing but a powerful stench

- DVDs

- bundles of cash

Your character’s car is also ripe with possibilities. Janet Evanovich’s Stephanie Plum drives a convertible Miata. Michael Connelly’s Lincoln Lawyer rides around in a Lincoln Town Car that doubles as his office. His chauffeur is a client who can’t pay his legal bill.

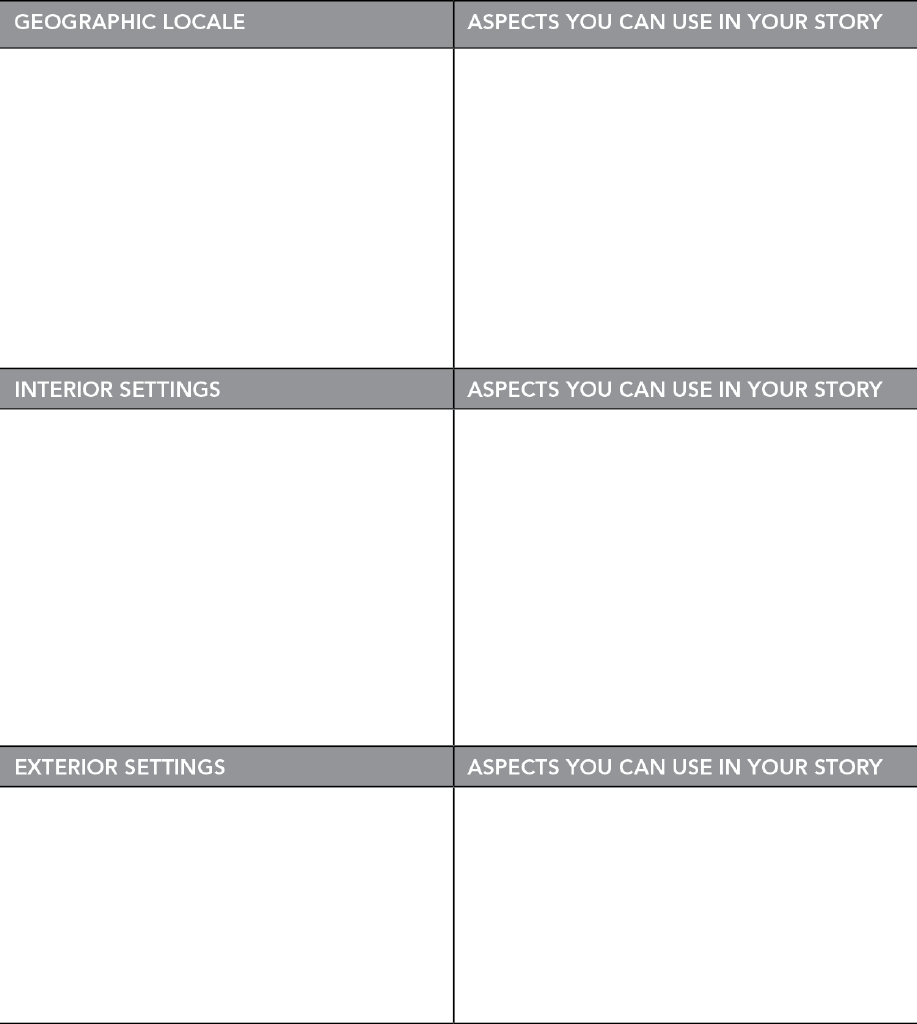

Now You Try: Imagining a Personal Space (Worksheet 8.5)

Think about your character’s bathroom and jot down the details that make this personal space unique:

Download a printable version of this worksheet at www.writersdigest.com/writing-and-selling-your-mystery-novel-revised.

MAKING A SETTING FEEL CREDIBLE

As a writer, your goal is not to re-create a completely accurate place and time—leave that to history books and travel guides. The last thing you want to do is bog down your story with pages of descriptive detail, no matter how evocative. Aim, instead, for credibility.

Whether a setting is real or imaginary, you need to know it inside and out before you start writing so you can create a credible sense of place. Put pink flamingos on suburban lawns in Chicago and you’ll blow your cover as a Floridian.

Plausibility is what counts. With a few strokes of physical and sensory descriptions—a few telling details—you can to bring a particular setting to life.

That’s where research comes in. How much research you have to do depends on how familiar you are with the setting you’ve chosen to write about and what resources you can access. I spent hours behind the scenes with a curator of the New-York Historical Society so I could plausibly provide a work setting for Evie Ferrante in There Was an Old Woman. To write Ivy Rose, the pregnant protagonist of Never Tell a Lie, all I had to do was remember what it was like when I was on leave from work, waiting to give birth to my first child.

Susan Elia MacNeal writes the Maggie Hope series set in Europe during World War II. Research informs this description of the interior of No. 10 Downing Street in Mr. Churchill’s Secretary.

Maggie Hope walked up the steps, past the guards and knocked. The door opened, and she was led by one of the tall, uniformed guards past the infamous glossy black door with its brass lion-head knocker, and through the main entrance hall. She passed through, barely noticing the Benson of Whitehaven grandfather clock, the chest from the Duke of Wellington, and the portrait of Sir George Downing. Then continued up the grant cantilever staircase. From there they took a few turns down a warren of corridors and narrow winding passageways to the typists’ office, ripe with the scent of floor polish and cigarette smoke.

Susan says that for settings in her books, “I try to visit the actual site if at all possible. However, for that paragraph, I couldn't actually go to No. 10 Downing Street—which is not open to the public—so I relied on books.” She found copies of out-of-print books like 10 Downing Street: The Illustrated History from Amazon and took a virtual tour of No. 10 online on a U.K. government-hosted website.

Even if your story takes place in a made-up time or place, the details have to feel believable and consistent. Draw maps of your locations, jot down the distances, and note the prominent geographic features. Refer to your notes as you write, adding to the map as you embellish the fictional place with realistic detail.

GETTING THE INFORMATION YOU NEED

Here are some suggestions for researching your setting:

- Go there: Pay a visit to the places where your mystery is set. Go as an active observer, not as a tourist or resident.

- Look at the people: Who’s there, how do they look, what are they doing?

- Look around and identify the props that define the place.

- Use all your senses: Are there distinctive sounds and smells?

- Check out the local newspaper.

- Collect maps, tourist guides, and postcards.

- Bring a tape recorder, a notebook, and a camera; capture the details.

- Talk to people who have been there: If you’re writing a police procedural set in a big city, talk to big-city cops; if you’re writing a cozy set in a New England inn, interview a New England innkeeper. Don’t know any innkeepers? Call or e-mail a couple of inns and plead your case. Many people are delighted to share their knowledge and expertise.

- Read diaries and letters: First-person accounts and memoirs are a rich source of information for the writer, especially if the setting is historical. There’s no better source for domestic detail, for example. Find them in libraries, in historical society archives, and on the Internet.

- Find newspaper accounts: Your library can give you access to newspaper archives where you may find photographs and stories to give you visual detail.

- Search the Internet: The Internet is full of images and descriptions of real places, as well as links to people with special interests and special expertise. Remember, though, much of what’s out there has not been vetted. Verify any facts that you want to include in your novel.

- Read books: With so much information available online, it’s easy to forget about books and libraries. For rich descriptions and photographs, check out travel guides and coffee table books that contain photo essays about a particular place. Buy them at bookstores or borrow them from the library, where you’ll find the writer’s best friend, the librarian. At Google Books or at online bookstores, you may be able to search inside the book and find what you need

- Be methodical: Impose a method on your information gathering. Some people copy facts onto index cards; others use spreadsheets or text files. Be sure to capture the information as well as its source.

On Your Own: Setting

- Compile a list of questions you need to research to create a convincing setting.

- Visit as many of your novel’s settings as you can; take along a notebook, a camera, and a digital recorder. Spend at least an hour observing and taking notes or recording.

- Research the settings you can’t visit. Consult books, magazines, newspapers, and the Internet, or interview people who have been there. Be methodical; record facts and their sources.

- Write a five-minute, half-page description of your protagonist’s home or office or car that could actually appear in the novel.

Complete the Setting section of the blueprint at the end of Part I.