Social services such as Twitter, Facebook, MySpace, and LiveJournal are an essential part of the hacker’s toolkit. Commonly known as the Social Web, these services provide a heretofore unprecedented data store of personal information about people, companies, and governments that can be leveraged for financial crime, espionage, and disinformation by both state and nonstate hackers.

In this new era of cyber warfare, the Web is both a battle space and an information space. As this chapter shows, it is also a social, educational, and support medium for hackers engaged in cyber operations of one kind or another.

This chapter also discusses security implications for employees of the US government, including the armed services, who use social media and how their activities can put critical networks in jeopardy of being compromised by an adversary.

In addition to the giant social applications mentioned earlier are hacker forums, many of which are private or offer VIP rooms for invited members. These forums, along with blogs and websites, provide recruitment, training, coordination, and fundraising help to support the hackers’ nationalistic or religious activities. What follows is a sampling organized by nation.

Social networking is very popular among Russians. A recent Comscore study shows that, as a group, Russians are the most engaged social networking audience in the world, spending an average of 6.6 hours viewing 1,307 pages per visitor per month. The United States came in ninth at 4.2 hours.

The Russian Security Services are quite aware of this and have expressed concern over violations of operations security by Russian military personnel via social networks such as LiveJournal, Vkontaktel.ru, and Odnoklassniki.ru. In fact, the Federal Security Service (FSB) has banned its members from using Classmates.ru and Odnoklassniki.ru. That ban does not apply to former military personnel, however, and that’s who is doing most of the posting today, now that a more rigid policy has been put into effect.

Numerous Russian LiveJournal users self-identified as former or present members of the FSB, Spetsnaz, Special Rapid Reaction Unit (SOBR), Border Patrol, and others.

Odnoklassniki.ru, however, has earned the attention of the Russian press and the Kremlin for a reason: it is rife with information of a military nature. As an example, one of Project Grey Goose’s researchers was able to find mentions of over 50 strategic assets in this Russian social network, including:

“Ordinata” Internal Ministry of Defence Central Command Communication Center

2nd special forces division of FSB-GRU

42nd secret RF Navy Plant

63rd Brigade of RF Internal Defense Ministry

Air defense ant-missile staging area for C-300

Air Paratroopers 38th special communication division

C-75 missile complex

Central Northern Navy Fleet missile test site—NENOKS Severodvisk Air map

FSB division of Dzerzhinsky range

Headquarters of Russian Strategic Rocket Forces (RSVN)

Heavy Navy Carrier “Admiral Gorshkov” location

K-151 nuclear submarine location

RF navy “Admiral Lazarev” missile carrier

RT-2M Topol (NATO SS-25 SICKLE) Mobile ICMB Launcher Base

Russian Akula Submarine K-152 Nerpa (SSN)

Russian Typhoon Class SSBN

Sheehan-2 Central Research and Testing Institute of Chemical Defense Ministry troops

The availability of this level of information has created a furor in various Russian online communities. One forum administrator complains that even the FSB doesn’t have the data about Russian citizens, institutions, and the armed forces and their movements and interactions that these social networks have, particularly Odnoklassniki.ru.

China has a huge Internet population and, as might be expected, has a correspondingly large population of hackers as well as servers hosting malware. There are literally hundreds of forums for hackers.

In his self-published book, The Dark Visitor, Scott Henderson wrote that he was astounded when he first began researching Chinese hacker groups. He had initially hoped to find a few Chinese citizens talking about their alliance, but what he ultimately uncovered was extensive, well-organized, and massive—a hacker community consisting of over 250 websites and forums.

The China West Hacker Union website, for example, had 2,659 main topics and 7,461 postings. This was a fairly average number of documents for a Chinese hacker website; some sites, such as KKER, had well over 20,000.

Unlike hackers from other countries, Chinese hackers tend not to use Facebook or other social networks, preferring an instant messaging service called QQ instead.

The following are websites utilized by Arabic hackers:

- http://www.arabic-m.com

Now defunct, this was the address for The Arabic Mirror website, where hackers advertise exploits. It contained a section devoted specifically to defacements related to the Gaza crisis, where the websites targeted were Israeli or Western and the “graffiti” contained messages about the crisis. The administrators identified themselves as The_5p3trum and BayHay.

The Arabic Mirror website has a password-protected forum with information about hacking and security vulnerabilities, among other subjects. Its moderator is Pr!v4t3 Hacker, who identifies himself as a 16-year-old from the Palestinian territories and a member of Kaspers Hackers Crew, which is involved in hacking Israeli websites.

- http://www.soqor.net

The Hacker Hawks website. is hosted in Arabic and includes an active forum with discussions on IT security and security vulnerabilities. Information intended to assist hackers in attacking specific targets is exchanged, such as vulnerabilities of certain servers, usernames and passwords to access administrator accounts for specific websites, and lists of Israeli IP addresses. The website may also facilitate financial crime: one post included a ZIP file allegedly containing a collection of credit card numbers from an online bookstore.

The Hacker Hawks website includes a forum called Hackers Show Off, where hackers boast of the Israeli and Western sites they have infiltrated. The site’s administrator, Hackers Pal, claims to have defaced 285 Israeli websites. The site also contains forums to share information on general hacking tools and skills.

- http://gaza-hacker.com/

The Gaza Hacker Team Forum is for sharing general information on hacking as well as a place to showcase the team’s skills and achievements. The Gaza Hacker Team is a small group that conducts both political and apolitical attacks. It was responsible for defacing the Kadima party website on February 13, 2008. The forum has a recruiting function: members can join the Gaza Hacker Team by displaying sufficient skills and knowledge on the website.

The administrators of the Gaza Hacker Team forum state that their goal is to develop a community around their forum. They post guidelines for members instructing them to encourage, support, and assist one another, and to focus on creating a sense of respect and community rather than the rivalry and competition present in other forums. “This forum is your second home,” states one administrator, “in which reside your friends and brothers to share knowledge with you and to share in your unhappy feelings when you are upset and in your joy when you are happy.”

- http://www.v4-team.com/cc/

This is the site of the Arabs Security forum, which is affiliated with DNS Team.

- http://al3sifa.com

This is the site of the Storm forum, which is also located at 3asfh.com. This is an Arabic language forum on hacking and other technical topics. Its members do not appear to be as heavily focused on Gaza-related hacking as the other forums. The forum was online in the early January 2009, but it was down as of February 1.

- http://arhack.net/vb

The Arab Hacker website contains several forums devoted to IT security and hacking. It includes forums devoted to making viruses, creating spam, and obtaining credit card numbers. It also includes a section for hackers to boast about their successes, where the focus is on American, Israeli, Danish, and Dutch websites.

- http://www.hackteach.net

The forum on this site is called “the Palestinian Anger forum” in Arabic and “Hack Teach” in English. It is run by Cold Zero and is one of the most active anti-Israel hackers. The forum contains tutorials and tools to assist hackers.

- http://t0010.com

This used to be a more developed website called the Muslim Hackers Library. Now it contains only a list of downloadable resources for hackers in both Arabic and English.

On December 24, 2008, the Whackerz Pakistan Cr3w defaced India’s Eastern Railway website with the following announcement:

Cyber war has been declared on Indian cyberspace by Whackerz-Pakistan.

When clicked, a new window opened saying that “Mianwalian of Whackerz” has hacked the site in response to an Indian violation of Pakistani airspace and that Whackerz-Pakistan would continue to attack more Indian military and government websites as well as Indian financial institutions, where they will destroy the records of their Indian customers.

Whackerz-Pakistan is motivated by both nationalistic and religious allegiances, unlike their Russian or Chinese counterparts, who are purely nationalistic. At least one of the members is Egyptian and two live in Canada, so their geographical identity may be less important than their religious affiliation.

Their stated preferred targets are India, Israel, and the United States, so besides their involvement in the Pak-India cyber conflict they may also be involved in the Israel-Palestinian National Authority cyber attacks.

At least half of its current membership are educated professionals in their 20s or older, so this is a mature crew with financial resources and professional contacts in the international technology community. The employment by one of its members at a well-known global wireless communications company means that they are potentially both an external and internal threat.

The Whackerz Pakistan operations security (OPSEC) discipline was generally poor. Quite a bit of personal information was available via the social networks YouTube and Facebook, as well as Digg, Live.com, and zone-h, but it was a Facebook entry that contained the most damning evidence: the real name of the leader and the order to a subordinate to perform the attack against Eastern Railway.

This example serves to underscore the level of trust that occurs, for better or for worse, on social networks. The most cautious member of this hacker crew, its leader, demonstrated good OPSEC on every social network except one—Facebook; probably due to the illusion of security provided by the Friends Only setting. The “illusion” stems from the fact that you never know who your friends truly are in a strictly online setting without the benefit of a personal meeting.

Social networks are an ideal hunting ground for adversaries looking to collect actionable intelligence on targeted government employees, including members of the US armed forces. The venue is free, raw data is plentiful, and collection can be done anonymously with little or no risk of exposure.

According to a recent study conducted for one of the US armed services, 60% of the service members posting on MySpace have posted enough information to make themselves vulnerable to adversary targeting. For those readers who aren’t versed in military vernacular, adversary targeting translates to events such as important new technology being transferred to the People’s Republic of China, a DOD intelligence officer being blackmailed, and the kidnapping and ransom of a corporate or government official overseas. The open APIs on Twitter and Facebook provide a virtually unlimited resource for building target profiles on employees of sensitive government agencies such as the Departments of Defense, State, Justice, Energy, Transportation, and Homeland Security. The Twitter stream adds a timeline for tracking when you’re at work, where you’re going after work, and what you are doing right now.

Another risk category is disinformation. Twitter received a lot of coverage during the Mumbai terror attacks of November 2008 for its role in covering the events in real time. Part of what emerged was the potential for terrorists to use Twitter to propagate disinformation about their whereabouts—for example, to announce a new attack occurring at a wrong address—thus adding chaos and confusion to an already chaotic situation.

Finally, there is the phenomenon of online trust. If you work in a targeted industry, sooner or later you will be approached by someone who isn’t who he claims to be for the purpose of gaining and exploiting your trust to further his own nation’s intelligence mission.

This section contains an official study for the US Air Force (USAF) on the risks associated with their service members using social media, specifically MySpace. It was produced by the Air Force Research Laboratory and has been approved for public release and unlimited distribution.

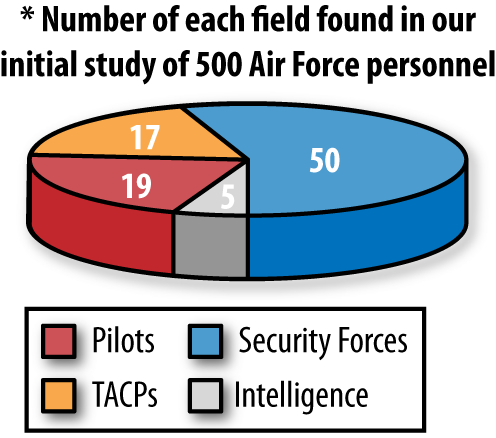

The study involved 500 individuals across the spectrum of job responsibilities, rank, family members, and length of service, and was meant to reveal vulnerabilities in OPSEC due to posting habits on MySpace, with the intention of carrying over the lessons learned to all types of social media. OPSEC violations constitute real risks from adversaries during wartime.

Although this report was prepared for the USAF, the report authors encourage all the armed services to consider how the same issues would impact their own operations.

The report authors posed two questions for the basis of their research:

What type of information and how much information are USAF personnel making available in MySpace?

What are the characteristics of the Air Force personnel who post information, and are they different from the larger population of Air Force personnel?

The 500 study participants were collected by searching MySpace using the keyword USAF. MySpace was chosen because of existing reports of OPSEC violations occurring there. Study information was collected by an anonymous MySpace account.

Sample profiles included active duty, national reserve, guards, cadets, recruits, retired, and recently separated members.

Information was obtained through simple keyword searches, such as “USAF cadet,” “USAF officer,” “USAF linguist,” “USAF special tactics,” “USAF intelligence,” “USAF deployed,” “USAF intel,” and “USAF cop.”

The results showed that posting to social networking sites is not restricted to younger service members and spans a wide variety of career fields (Figure 6-1).

- Helicopter pilot currently in California, headed to Nellis AFB to work at the 66th Rescue Squadron

OPSEC concerns include sharing his new duty station, his new unit, the aircraft he’ll be piloting, and his status as a volunteer EMT and firefighter (which could provide an adversary with a means of approach).

- F16 pilot and instructor currently stationed in California

OPSEC concerns include sharing his rank, his duty location, the type of aircraft he flies, the fact that he is an instructor, past squadrons, personal medical information, and family information.

- TACPs and Security Forces

They share notes about deployments, units they deploy with, and information about training as well as where they work.

Posting pictures of themselves at deployed locations can provide the enemy with an opportunity to identify potential targets.

- Intel students, officers, imagery analysts, crypto-linguists, and predator sensor operators

OPSEC concerns include that they self-identify as intelligence professionals, and mention bases, training locations, and job duties.

MySpace group site pages are another problem because they provide information about specific career fields and specific operations in the form of reunion pages (i.e., Bosnia, OIF, OEF operations, etc.). Current MySpace groups include USAF Wives, USAF Security Forces, USAF TACPs, USAF F-15 crews, USAF Air Traffic Controllers, and Pararescue.

The following are potential adversary scenarios:

- Kidnapping scenario in Iraq

Lt. Smith keeps a daily journal, with pictures, on her MySpace account of what she does in Iraq. As a result, an adversary is able to locate and kidnap her.

- PRC technology transfer

Dr. Joe Smith (GS-14) is a scientist employed by the USAF at Wright Patterson Air Force base’s AFRL. He becomes a target of Chinese intelligence.

- Blackmail scenario of USAF research officer

Lt. Col. Joe Smith has what he believes is an innocent MySpace page. It was intended for him to keep in touch with his family during deployments, as well as with other F-22 pilots in his unit. He becomes a target of blackmail.

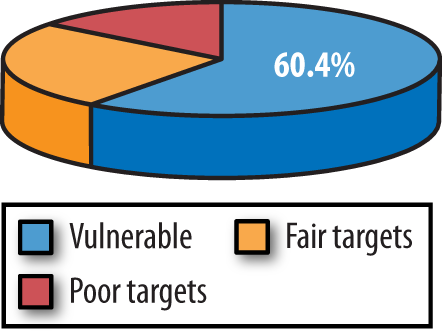

60.4% of USAF personnel posting on MySpace have provided sufficient information to make themselves vulnerable to adversary targeting (Figure 6-2), including seven critical variables of information:

First name

Last name

Hometown

Home state

Duty location

Public account

Job type

25.4% were found to be fair targets, and only 14.2% were found to be poor targets (not vulnerable).

On May 1, 2009, a French hacker going by the alias of Hacker Croll announced that he had penetrated Twitter’s security and accessed its company records. (Twitter is a popular microblogging service.) Screenshots of a few of them were posted as proof on a forum at zataz.com, a French website.

This was the second time in 2009 that Twitter had a breach in its security (the first being in January by a hacker named GMZ), and also for the second time, Twitter CEO Evan Williams announced that a “thorough, independent security audit of all internal systems and implementing additional anti-intrusion measures to further safeguard user data” would be done.

Williams also claimed, much to Croll’s chagrin, that no important files were accessed, nor was anything taken.

Deciding to teach Twitter a lesson and provide a warning to corporations everywhere, Croll sent a zipped file of over 300 Twitter documents, including financial statements and executive memos and meeting notes, to TechCrunch, a popular and influential IT website owned by Silicon Valley entrepreneur Michael Arrington.

TechCrunch created a firestorm of controversy on July 16, 2009, when it published a number of the stolen documents on its website.

TechCrunch followed that up with a detailed accounting of exactly how Hacker Croll accomplished his break-in. He didn’t use any hacking tools, Croll told reporter Robert McMillan for a May 1, 2009 article for IDG News:

“One of the admins has a Yahoo! account, I’ve reset the password by answering to the secret question. Then, in the mailbox, I have found her [sic] twitter password,” Hacker Croll said Wednesday in a posting (http://www.warezscene.org/hacking/699733-twitter-got-hacked-again-3.html#post1312899) to an online discussion forum. “I’ve used social engineering only, no exploit, no xss vulnerability, no backdoor, no sql injection.”

According to the information that Croll provided to TechCrunch, here is the rather simple process that he followed to crack Twitter’s security and gain access to its files.

Using publicly available information, he built a profile of the company with emphasis on creating an employee list.

For every employee identified, he looked for email addresses, birth dates, names of pets, spouses, and children.

He began accessing popular web services that each employee may have had an account with (e.g., Gmail, Yahoo!, Hotmail, YouTube, MySpace, Facebook, etc.), and using the discovered email address as the username (which frequently is the case), he initiated steps to recover the password. Passwords are often answers to standard questions, such as “What is your mother’s maiden name?”, or the service may provide an option to email the forgotten password to a secondary email address. This is where Hacker Croll’s patient discovery of personal data combined with flawed security design and sheer luck to enable a successful hack.

Croll tried to access a Twitter employee’s Gmail account. He opted for emailing the forgotten password to a secondary email address. Gmail provides users with a clue as to which email address they had picked by obscuring the first part but revealing the service (***********@hotmail.com). Once he saw it was a Hotmail account, Croll went to Hotmail and attempted to log in with the same username. Here is where luck stepped in: Hotmail’s response to Croll’s login attempt was that the account was no longer active. Croll immediately re-registered the account with a password that he picked, then went back to Gmail and requested that the forgotten password be emailed to the secondary account, which Croll now owned. Gmail reset the password and sent out a new one to the Hotmail account, thus giving Croll full access to a Twitter employee’s personal email.

His next task was to discover the original password and reset it so that the employee would never suspect that her email account had been hacked. Thanks to Gmail’s default of storing every email ever received by its members, Croll eventually found a welcome letter from another online service that, for the member’s benefit, fully disclosed her username and password. Recognizing that 99% of web users stick with the same password for everything, he reset the Gmail password to the one he just discovered, and then waited for the Twitter employee to access her Gmail account. Sure enough, the employee soon signed in, sent a few emails, and signed out, never suspecting a thing.

Now armed with a valid username and password, Croll dug further into the employee’s Gmail archives until he discovered that Twitter used Google Apps for domains as their corporate email solution. Croll logged in with his stolen employee username and password and began searching through all of that employee’s company emails, downloading attachments, and, in the process, discovered the usernames and passwords for at least three senior Twitter executives, including CEO and Founder Evan Williams and Co-founder Biz Stone, whose email accounts he promptly logged into as well.

Croll didn’t stop there either. He continued to expand his exploitation of Twitter data by logging into the AT&T website for cell phone records and iTunes for credit card information. (According to the TechCrunch article, iTunes has a security flaw that allows users to see their credit card numbers in plain text.)

The end result can be seen online, as TechCrunch published some of the stolen information, and the rest will probably find its way online eventually through other channels.

Although this real-life example of computer network exploitation (CNE) did not involve a government or military website, the essential process is the same. Had this been a successful SQL injection attack instead of a pure social engineering attack, all of the usernames and passwords would have been discovered in a matter of minutes and a full dump of the contents of the company’s database would have occurred.

Twitter may soon become the world’s largest SMS-based channel of communication. It is already being exploited by the intelligence services of numerous nations, thanks to the publicity that it has received during the Iran election protests and last year’s Mumbai terror attacks. One of the many take-aways from this unfortunate event is that the users of social software applications (Twitter, Facebook, etc.) should immediately institute strong passwords and usernames and change them frequently, and each user should be more cognizant of the amount of personal data that he reveals in cyberspace.

The advent of social software and its rapid popularity has transformed the way that intelligence organizations around the world can collect information on their adversaries.

Both the United States and the Russian Federation armed forces have been struggling to find a way to prevent, reduce, or control the spontaneous writings of their troops on their personal web pages in a variety of social media, which often reveal far too much information on matters impacting OPSEC. If this information is scraped, filtered, and aggregated properly, it can easily provide an asymmetric advantage to one’s enemy.

For an intelligence operative who is seeking to recruit and turn a person employed in a sensitive position, social software is a dream come true. No longer do case officers have to rely solely on arranging in-person meetings or one-to-one engagements to build relationships that may lead to turning a foreign service officer into an espionage asset, for example.

Today, almost the entire recruitment process can be done online, from finding likely candidates to building out a profile, to crafting an online presence with a backstory that will act as a suitable lure.

The new case officer might very well be a social network analyst familiar with the open source information retrieval library called Lucene, Hadoop for scaling thousands of nodes of information, and Nutch for data retrieval, parsing, and clustering—all fed by the APIs that each social software service have conveniently created to entice developers to build new, fun applications on top of their platforms.

Spook Finder 1.0, anyone?

A more sophisticated alternative is the use of robots (bots) that, with the right programming, can appear online as a genuine person.

The following content was provided by a Russian technologist and member of the Project Grey Goose team at my request. It represents, at the time of this writing, a serious and emerging threat present on Russian social networks, but Project Grey Goose investigators expect to see these capabilities migrate over to Facebook and other social software sites in the very near future.

Automation and simulation of artificially created activities performed inside Russian social networks (vKontakte.ru and Odnoklassniki.ru) are virtualizing communication to the degree that one cannot be certain of who he really is becoming friends with.

In a normal social network scenario, a user would create a profile, upload a couple of pictures, record his ties to universities and/or place of work in the profile, and, for the most part, then be ready to find and begin socializing with friends or colleagues. But how does one tell the real thing from a virtual mock-up?

That is what’s happening right now in the Russian social networks VKontakte.ru and Odnoklassniki.ru. Virtual entities are pretending to be real people in a way that enables criminals to gather personal information from the unsuspecting.

If a social network relies on a system of “votes” or ratings to validate trust, getting most of them to elevate the “trust” to an adequate level already can be automated.

If a site is vulnerable to a cross-site scripting attack, thousands of users can be affected within mere seconds, just by pushing a button on the operator’s workstation.

If a group of people does not like a particular participant or the site itself, it takes only 10,000 rogue users connecting simultaneously to bring the server down and cause denial of service attacks.

If one needs a user’s trust or password (which is very close to being the same thing in certain circumstances), there’s nothing to prevent the operator to invite unsuspected users to a social honeypot, a virtual society created by the attacker to lead “the herd” to adversarial actions.

These mechanisms exist today in the Russian cyber underground and are available at a very affordable price.

The following scenario may be fully automated:

Find valid user account/IDs.

Register thousands of new accounts, with random data, organizing newly created profiles in groups.

Create new groups with hot topics, generating traffic to these new artificial groups.

Invite new members, either through mass-sent or targeted-search messages, to participate in the artificial groups.

Hook some form of exploitation mechanism to the visitors.

The following applications are available for purchase using the anonymous payment system known as WebMoney:

- ID grabber–I

Iterates through valid IDs, finding new user IDs that become active on the system through scenarios or custom search parameters.

Price: 44 WebMoney dollars

- Automated registration

Automatically registers multiple account in the social network with custom profiles with granular detail capability, starts services, uploads random photos, fills out the “user’s” interests, and connects them to random places of work and study.

Price: 55 WebMoney dollars

- Automated searcher

Searches for specific accounts, inviting them to the automated, custom-created groups.

Price: 50 WebMoney dollars

- Automated group creator

Creates groups by interest, by location, by age, and so on.

Price: 44 WebMoney Dollars

- Buying/integrating XSS exploit

Creates a cross-site scripting exploit for the social network and embeds it into the newly created pages.

Price: 100–1,000 WebMoney dollars

Once the user is trapped inside this virtual circle of automated “friends,” it is very hard not to follow through and not to accept friendship from at least one of the zombies peacefully trying to make contact under the guise of someone you might have worked with years ago.

So aside from exploiting the users, stealing their private data, and trust and relationship mapping to other legitimate users, what else could be on the attacker’s mind?

How about a reverse denial of service on the server itself?

If one account in Vkontakte.ru can have a maximum of 2,500 “friends” in his social network, and the attacker is able to create an unlimited number of accounts by utilizing proxies and linking them to other users or to each other, what would it take to create an automated script to initiate massive traffic among those zombied accounts without the use of any external entity or owning a powerful external botnet?

The answer is not much, really. Depending on what logic is being put behind the attack, only one remote login with the proper command initiation can trigger a chain reaction that can bring down the network from the inside.

The problem is not isolated to Russian social networking sites; it’s just that the local underground is currently more interested in testing where things may go until the path is verified for making some form of guaranteed profit.

Also, it’s much easier to converse in your own language and within your own culture, and use social engineering techniques for exploitation. However, all of that can be overcome if there is enough money to be made.