CHAPTER 11

Transportable Content

We’ve talked a lot about what you can do with structured, smart, reusable content. But guess what? You’re not the only one who‘ll want to shovel it around the Internet. Your users likely will, too, shifting your content from wherever you put it into their own preferred destinations for reading, sharing, and using it.

You can already see this in action with hugely popular services like Pinterest, where users install a bookmarklet in their browser and “pin” images and video they like to “boards” of their own—creating collections of content around topics like vacation ideas or interior design inspiration. It’s also the crux of read-later apps like Safari’s Reader, Readability, Instapaper, and Pocket (formerly called Read it Later), which at a quick click or tap take content from its source and pull it into a user’s own collection on that service’s servers, allowing her to read it later in a clean, clutter-free interface (as shown with an example from Salon.com, then displayed in Readability, in Figures 11.1 and 11.2).

It’s even cropping up in more niche services like Gimme Bar—where users can collect not just images and video like in Pinterest, but also complete screen shots, text snippets, audio, and other content—and Svpply, which allows users to create collections of products they want, browse and mark the collections of others as favorites, and click through any product to shop on a retailer’s website.

FIGURE 11.1

An article about the acclaimed TV show Breaking Bad on salon.com, where it’s surrounded by plenty of distraction.

FIGURE 11.2

The start of that same article pulled into Readability, where the content now runs the show.

Each of these examples offers users a different design and features, but they all come back to the same central theme: giving users the power to pluck a piece of content from its original location and shift it to another context. Unlike bookmarking the page, which just creates a link to the content, these services are actually helping users put that content in their digital pocket, so to speak, and carry it around with them.

NOTE WHAT IS CONTENT SHIFTING?

Content shifting, as I use it in this chapter, is the process of taking content from one context—as in, a specific website or application—and shifting it to another location. People shift content for a wide range of reasons. They may want a cleaner interface for reading, seek to save the content for later, include the content in a collection of similar pieces, or need to access it at a time when they won’t have an Internet connection. Whatever the reason, though, people are shifting content more and more often—and tools are cropping up left and right to help them do it.

In this chapter, we’ll talk about how content is becoming more transportable—oftentimes, whether you want it to or not—as well as the opportunities, challenges, and ethical considerations at play for those creating, managing, and organizing that content. Finally, we’ll explore where this emerging trend may go in the future, and what you can do to not just deal with it, but help shape it.

The Great Content Shift

Our transformed relationship with content is one in which individual users are the gravitational center and content floats in orbit around them.

—Cameron Koczon1

A few different terms have cropped up for this new form of content transportation and consumption, including time-shifted content, portable content, and orbital content, as Koczon—part of Fictive Kin, the startup behind Gimme Bar—coined it. Whatever you call it, all these phrases point to the same reality: While users may want your content (and if they don’t, you should stop right now and go fix that problem first), they don’t necessarily want to get it on your website.

Instead, they want it in the place that’s most comfortable for them, and from which they can easily share it and save it for later. They also want to turn pieces of content from lots of different sources into their personal collection—not a list of bookmarks, but a compilation of the content itself.

This presents a big mental shift for many of us. After all, we’re used to the model we made two decades ago—a model where people “surf” (or, since it’s not the ’90s anymore, “browse”), find your stuff, and come back to it whenever they want to see it again.

It’s not that this behavior no longer exists. For the foreseeable future at least, plenty of folks will still type in your URL or add your site to their favorites menu. The difference is that now, that’s just one way information will be consumed.

It’s hard to pinpoint a single reason for this shift, but I’d argue it’s got a lot to do with the amount of content each of us is coming in contact with online. Tweets and news articles and blogs and products seem to pop onto the collective radar incredibly quickly, and to whiz by faster than anyone can reasonably keep up with. In all likelihood, your users are feeling overwhelmed, and they’re looking for a way to keep up with the flow and make sense of the things that are important to them. These services can help them easily save the interesting bits that would otherwise flit by, avoiding the painful experience of trying to recollect who shared which link and then searching through pages of updates to find it again.

But that’s not all. This shift also seems like a clear response to the problems with the online reading experience. As we touched on in Chapter 10, “Reusable Content,” sitting down with a long read online often results in a frustratingly distracting experience—one where the actual content receives so little page real estate, it’s hard to even tell what you’re looking at. Standing in stark contrast to print design, where pages are often lovingly laid out once content and imagery are complete—beautifully showcasing typography, photography, and design elements that contribute to the story—online versions often weigh readers down with a metric ton of advertising, all of it seemingly blinking and expanding and taking over the screen until you can barely see straight.

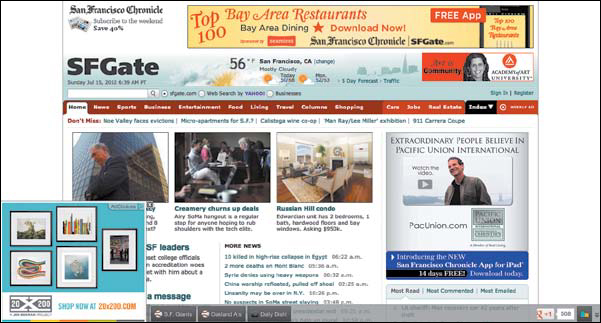

Take the example from SFGate shown in Figure 11.3, where I’m hit with multiple banner ads, two types of advertising for other products from the Chronicle, and even an annoying ad for art print retailer 20x200, “retargeted” to me because I’ve visited the retailer’s site before.

Now, SFGate relies on that advertising to support its business model, so perhaps you could argue it has an excuse for creating such a cluttered reading experience. But what about sites that don’t rely on advertising revenue? Many of them are still cluttering up their content with endless noisy distractions, like the GoDaddy hosting page shown in Figure 11.4, which seems to desperately want you to buy something (though with all the clutter, I have a rather hard time figuring out what).

FIGURE 11.3

Noise, noise, noise: three banners, one expandable ad overlay, and two ads for the Chronicle’s other products take over the first few hundred pixels of SFGate.com.

FIGURE 11.4

Yet another reason to never use GoDaddy: overwhelming, cluttered, and way-too-pushy pages that make it nearly impossible to know where to go and what’s important.

In the face of the myriad less-than-reader-friendly experiences users face every day, is it any surprise many would rather skip your site altogether and transfer the content they want to a place that’s been designed around...you know...reading?

Finally, people are still human when they go online. And humans want to connect with others, share the things that matter to them, and be social. As more and more communication takes place online, it’s no surprise people want to use digital platforms to share content and show one another the things they’ve been collecting, coveting, and reading as well. The digital possibilities may be new, but the desire to share and compare is anything but.

What’s in It for You?

So we can see why a user might want to save, shift, and share your content. But why should you embrace this movement, too? What’s in it for content creators and publishers—and those who help them plan and organize online experiences—anyway?

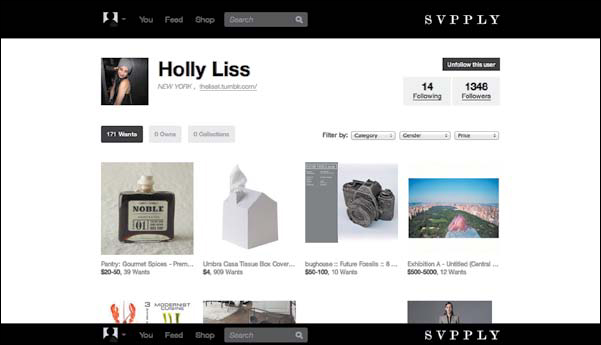

For one, it’s a matter of making your content easier for new audiences to discover it and share it with others, as Svpply does very well. With this service, users create collections of products they want. Others can “Want” that product, too, with an action not unlike the Facebook Like button, as shown in Figure 11.5.

FIGURE 11.5

Svpply’s approach: Let users pluck products they love, create personal collections, and share them with one another. From here, it’s easy to click through to buy the product directly from the seller.

If you’re a retailer, there’s nothing better than other people putting your content front and center for their friends and followers to see it, click on it, and—you hope—buy it.

While this sort of content collection is a no-brainer for ecommerce, the benefit of greater content syndication extends beyond products. In any industry, if you have content that helps people solve a problem or complete a task—while also remaining somehow relevant to whatever your products or services actually are—then you’d benefit from getting more people to know about that content.

It’s not all about increasing your reach, though. Another big—and often ignored—benefit to embracing content shifting and sharing services is that you’re building deeper connections between your users and your brand. Think about it this way: when users pocket your content for their personal collection, they’re essentially saying that your stuff is worth keeping. They’re not taking content away from you; they’re taking a piece of you along with them. And that’s a powerful thing.

Taking Advantage of Content Shifting

As you’ve probably already guessed (this book has a theme, after all), one of the biggest ways you can make your content work better wherever it’s being viewed is by giving it structure. Why? Because when your content has structure that’s machine-readable and ready to be parsed, it’s much easier for those content-shifting services to keep the intent of your content intact, retaining elements like bylines and datelines, displaying copy decks in distinctive large type, and generally leaving you with a layout that still communicates what you intended.

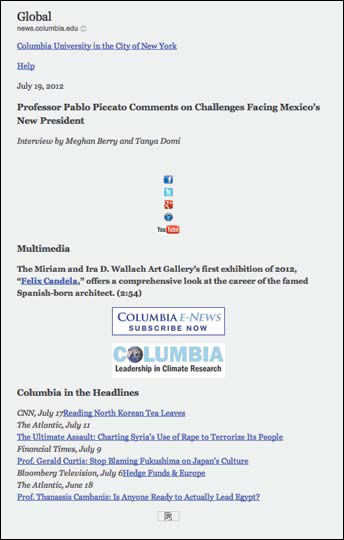

But if you’ve used things like font size and bolding to differentiate parts of content, those services will have a much more difficult time knowing what to do with them—and that makes for content that causes some problems when it gets shifted. For example, take a look at an article from Columbia University’s news section, shown in Figure 11.6, and that same article displayed with Instapaper in Figure 11.7.

“That’s OK,” you might say. “At least it looks good on our site.” But you know who suffers when your content parses poorly? Your users—the people who liked your content or product enough to share it and save it for later.

FIGURE 11.6

An article from Columbia University’s news section, featuring a video and Q&A with a professor.

FIGURE 11.7

That same article displayed via Instapaper—except all the content’s missing! While scrapping the video was expected, what happened to the Q&A? All that’s left is some out-of-context “related content” and social links from the sidebar.

Instapaper actually already offers publishers guidelines for making their content ready for parsing, providing specific tags that make it easy for Instapaper to understand the content’s title, date, author, and body, and also to ensure all parts of multipage pieces are pulled in.2 This is a good start, because it gets everyone thinking about content chunks.

The problem is, it’s too specific to one output (Instapaper) and to one type of content (articles). If you want to prepare your content for a future that’s all about unknowns, you can’t rely on marking it up for individual destinations. If you do, you’ll end up with a mess of code that must be updated each time a new service is unveiled.

The good news is, by applying the skills learned throughout this book—breaking content down, storing it in modular parts, and using metadata and markup to keep its meaning intact—you can keep your content making sense for your users, even when it’s shifted.

Plus, when it comes to content shifting, we’re just getting started. As we’ll talk about next, there’s lots to work out when it comes to issues like attribution, circulation, and compensation. Which means if you have content structured according to its meaning and stored with solid metadata now, you’ll be ahead of the game as new standards emerge for marking up content for shifting contexts.

More Portability, More Problems

Content shifting is fascinating, but it’s not a simple topic. The idea of users plucking your content from one location and consuming, sharing, and saving it somewhere else can be scary, especially if you’re working with a site that relies on advertising to support its business model. Just like television executives got wide-eyed and terrified when they first saw TiVo—“What’ll we do if everyone just speeds past the commercials?”—today, publishers and their legal counsels have plenty of reasons to fear content that’s been shifted away from its original context.

When you look carefully, this fear of content-shifting, saving, and clutter-removing apps is actually about more than money (though that’s certainly a large part of it). It’s about three closely interrelated issues: attribution, copyright, and compensation.

Let’s look quickly at each problem and some solutions.

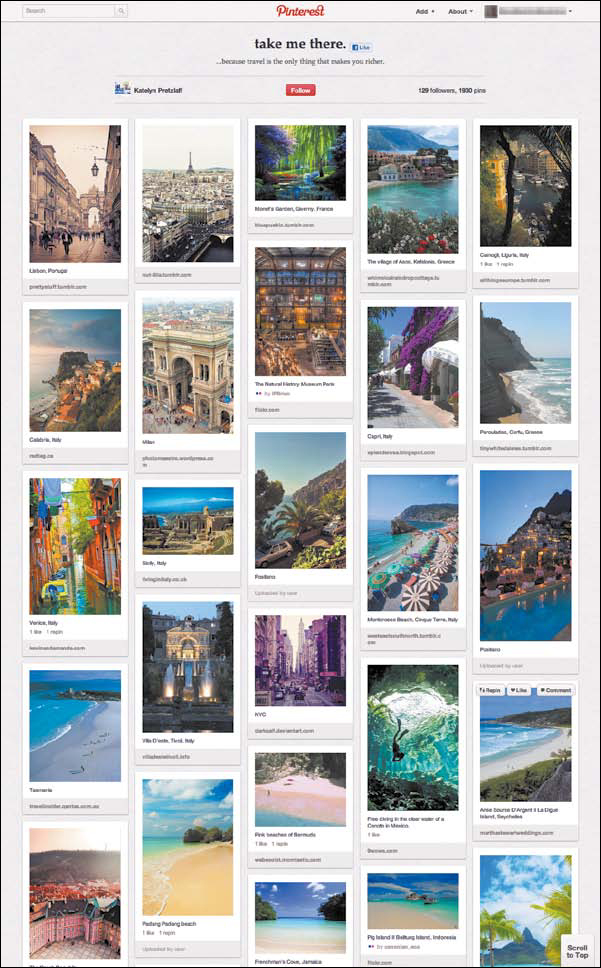

Attribution

Take a spin through Pinterest, and you’ll find thousands of beautiful images: high-fashion photography that looks like it could be straight from the pages of Vogue; gorgeous architectural shots that would make any designer drool; stunning landscapes and exotic travel destinations, like those shown in Figure 11.8. But where do they all come from?

Sure, you can tell what site they were pinned from, and get a link back to that page. But there’s no actual attribution to be found—and no metadata that comes along with each image. Instead, when a user plucks a picture and pins it, as of this writing, Pinterest hosts that image on its servers, stripping away any descriptive content that was once with it.

When content-shifting and sharing services pull content from one location and place it in another without including any attribution, it’s no surprise that those creating content—such as professional photographers—might get a little antsy. At the same time, this problem isn’t new. Whether you look back a couple years to Tumblr’s rise or a couple decades to the mixtape, people have been plucking content from one place and saving their own versions of it for quite some time. It’s simply now much easier to do—and, perhaps more important, easier to see just how many people are doing it.

FIGURE 11.8

A typical Pinterest board, featuring photos collected from across the Web and arranged in the site’s signature minimal style. But where do these images come from, and who owns them? It’s hard to say.

Copyright

When you shift content from its original location to your preferred destination—whether you’re saving it to your desktop, pasting it into a Word document, or using one of the services we’ve talked about in this chapter—you’re copying it, plain and simple. And when you start talking about copying, you pretty much can’t avoid talking about copyright.

While attribution deals with keeping track of where content is from and who created it, copyright is about something subtly different: whether or not someone else has the right to reproduce the work. But reproduction alone doesn’t constitute a copyright violation. Many of these services consider what they do to be fair use—that is, a legal reproduction of copyrighted material that doesn’t require permission—because they’re enabling users to save content for personal use, rather than copying it for their own distribution.

Thing is, copyright is a tricky subject in the United States, where most of these services are centered, because it’s decided on a case-by-case basis—and while there are fair use guidelines, they’re all relative and open for a judge’s interpretation: how much of the original work is being reproduced; whether the content’s meaning is transformed in the process; whether the reproduction affects the value of the original; what sort of entity is reproducing the work; etc.

With so many factors involved, it would be hard to say exactly where each service falls in legal terms without a few expensive, soul-crushing court battles taking place. But what is clear is that many content creators aren’t happy with the way their copyrighted materials are being used—and some, particularly those that are well organized and can afford the legal fees, are likely to push the copyright issue front and center soon.

Compensation

This, of course, is the kicker for so many content creators. Lots of people make money off digital content, typically via advertising revenue. So it’s no surprise that when users shift that content and strip the ads away, those who build their business on advertising get a bit upset.

Readability tried an experimental approach to solving this business-model problem: actually paying the publishers whose content was shifted using Readability. For about a year, Readability’s publisher payment program accepted subscription fees from users, typically $5 a month, and set aside that money to pay the publishers whose content was being consumed via Readability’s products. By tracking how often a given publisher’s work was read using the service, Readability hoped to distribute the money it received fairly, and in the process, to make progress toward a new model for paid content.

But Readability discontinued the program in the spring of 2012 because too few publishers participated, and most of the funds earmarked for publisher payments had gone unclaimed. With more than $150,000 in a bank account meant to pay content creators and producers, Readability disbanded the program and donated the bulk of its coffers to charity.

Of course, Readability isn’t the only organization trying to come up with alternatives to the advertising business model. But despite all the Kickstarters and other services out there, it’s clear no one has a workable answer to the compensation question yet—and most publishers, already obsessed with pageviews and continually adding clutter to their sites, are struggling to do much besides get riled up and angry.

Attribution, copyright, and compensation are weighty issues, to be sure—issues I’m pretty hesitant to predict the precise future of. But all said, it’s easy to paint those presenting us with new content-shifting services as the bad guys: malicious startups trying to make a splash by further eroding online media’s already crumbling business model. But I’d argue that’s too easy—and, moreover, that those of us who work with content are a part of the problem, because we’ve failed to rethink what our content means in an online, unbounded world.

Those who are experimenting, building things like Safari Reader, Instapaper, or Pinterest? While their own business models may not be figured out yet either, and while their ability to parse content’s meaning and support it with solid attribution may still need work, they’re taking necessary first steps toward finding a model that makes sense in a digital world.

Are you going to take steps, too?

What You Can Do

So readers are frustrated, people like to share, applications are experimenting, content publishers are crying foul, and business models are collapsing. Amid the hubbub, what should you actually do about it?

Many organizations are reacting by trying to rein in content that’s being shifted and shared, preventing people from saving it for later, sharing it with their friends, or shifting it to a more reader-friendly layout. And it’s perfectly understandable why. If these new technologies and services allow a user to strip away everything she doesn’t want and just take the content that matters to her, then what loyalty does that user have to the place she got the content? Will she even know where it’s from? Will she care?

We don’t have all the answers, but I’d argue your best course of action is to think of the people who want your content in their collection as allies waiting to happen. They care about you. They think you’re great. So you can alienate them by being stingy, or you can turn this into an opportunity for you—by being an active part of this shift, rather than someone this shift happens to. Here’s how.

Be Part of the Experiment

Experimentation isn’t just for startups. In every field, we need folks willing to experiment with new ways to publish, share, pay for, and circulate content. After all, it’s beyond obvious that the old pay-per-eyeball thing isn’t working, and that too often, it’s the content creators who are left in the lurch, paid peanuts for what’s often thoughtful, researched, complex work.

If you care about solving the problem, then your first step is to get comfortable experimenting, too—to accept that this isn’t all figured out yet, and to be willing to do things differently and see what happens. From launching Kickstarter campaigns to fund content projects to publishing a long article as a Kindle Single—a short ebook that Amazon sells for just a few dollars—there are lots of avenues to explore once you stop clinging to the old model. That doesn’t mean any of them are perfect, but they’re a place to start. And they won’t get better unless we work on them.

Improve the Reading Experience

Lots of times, you hear publishers and retailers say they want to design experiences that are “sticky”—that users will stay with for a long period of time and come back to frequently. One way to do that is to focus in on creating a great reading experience—one where the content takes center stage, and where visual cues help the reader focus and immerse, rather than become overwhelmed and distracted. After all, what better way to keep people from shifting your content to a reading service than to make your own site a comfortable place to read?

It might not be realistic to strip away every bit of supplementary content or call to action or advertising from your site, but it’s worthwhile to take a hard look at all the stuff you’re publishing and ask whether it really matters. If it doesn’t, it’s time to cut the cruft—before your users cut your site.

Letting Go

We don’t know what will happen as more people start to experiment. Services will launch and die out; innovation will be frequent, but disjointed.

Yet we do know this: When we stop wasting our time thinking about the “pages” where our content “lives,” we can start thinking about all kinds of new opportunities and ideas. We can come up with new ways to create and distribute packages of information that work together—and travel together.

We can discuss new ways to track content circulation, embedding information in our content about where it’s been and how often it’s been used. We can experiment with new business models using the expertise of people on both sides of the equation: those who create great content, and those who appreciate it.

The point is, none of these problems has been solved just yet, and you won’t have all the answers anytime soon. But if you want to be part of the group dedicated to figuring it out—and benefiting from the result—then you’ve got to let go: of outdated ideas about location and ownership; of concern for controlling every bit of your users’ experience; of fear about where your content might end up. Because until you learn to let go of the past, you can’t embrace—and be part of building—whatever’s next.

Of course, it’s not just that issues like attribution—or, for businesses that use content to gain loyalty and sell product, losing brand voice and messaging—aren’t valid. Having your content lose its provenance is a very real concern, and one that only gets more important as content gets further away from the people making it.

But the truth is, there isn’t any other option—not really. Your users aren’t going to stop expecting to collect content and tote it around with them, and your organization is going to have a hell of a time trying to nail it all down.

Instead, letting go is all about committing to two things. First, you must accept that your content will be shifted and moved. You can find flaws in the business models of today’s content-shifting services (and they do have many, no doubt). You can be wary of those who want a piece of your content, yet seem unencumbered by morals.

But the content itself? It’s going to move beyond your control.

Second, you need to invest in content that’s worth remembering—not necessarily for where it was found, but for what it meant and how it communicated that meaning. Great content is memorable, and being memorable is about more than your URL. It’s about your voice, your message, and your ability to help others.

When your content does that, when your audience finds it and feels like it’s intrinsically you—it’s so much yours that it couldn’t possibly be anyone else’s—then in some ways, it matters much less where they found it.

But accepting that you can’t control your content is going to take more than some structure and metadata, especially in an organization that’s still thinking about controlling its message and maintaining the perfect PR spin. If your organization is obsessed with broadcasting its message—rather than allowing customers to define their own experiences—then you’re only going to get more uncomfortable as the future unfolds.

So now that we’ve looked at myriad ways that your content, once it’s structured and self-descriptive, might be adapted, reused, reprioritized, connected, dissected, and transported to meet the needs of a changing Web, it’s time we take things one more step. In addition to changing our content, it’s time we look at how to change our organizations themselves, and shift the role of content in the enterprises we work in or support. To do so, we’ll now explore how organization-centric thinking harms organizations, creating lots of noise but leaving the signal to wither—and what you can do to stop it.