Figure 17-1: Creiglingen Reflections #2

Compare this image with figure 14-2c. I found this plate glass window with reflective mylar behind it, giving two reflections—one straight; one distorted—in the small town of Creiglingen, Germany. I was there with photography friends, and we had a ball making multiple images over a period of nearly an hour. Were we simply having fun? You bet we were! We were moving around and whooping it up. Moving just a step or two in the middle of the street completely changed the interaction of the two reflections. Under such circumstances, it’s worthwhile to make multiple exposures, selecting the best ones later and deleting the rest. (Too often people expose multiple images for no discernible reason. It’s wise to be sensible about this aspect of photography.)

CHAPTER 17

Approaching Creativity Intuitively

![]()

IF YOU’RE GOING TO ACCOMPLISH ANYTHING IN PHOTOGRAPHY, you’ll have to enjoy doing it. This not only applies to photography, but to any field. It’s close to impossible to do well in any endeavor that you hate doing. You have to enjoy doing it, have fun doing it, and look forward to doing it.

With that thought firmly in mind, if you enjoy doing photography, make it even more enjoyable by trying new things periodically. Of course, some of those new things will be duds . . . totally useless attempts that yield nothing of value. But once in a while, a new approach—perhaps new subject matter you’re photographing, perhaps a very different approach to well-known subject matter, perhaps a new way of post-processing or darkroom printing—will yield startlingly good results. Those successes will vault you into whole new realms of enjoyment and creativity. In many ways digital photographers are ahead of film photographers—largely due to the fact that “pixels are free.” Digital photographers are more willing to photograph anything and everything just to see what comes up. There’s no harm in that approach.

While it’s important to get some basic understanding of the technical aspects of your art, you don’t have to be a master of everything before applying what you know. The important things are to enjoy what you’re doing and to be pleased with what you’re producing.

This has proven to be the case with me, personally. My jump into digital allowed me to start doing things I had never done previously, such as take pictures out of commercial airplane windows and do extreme macro close-ups. I had, in fact, done many extreme close-ups in black-and-white and in color with my medium format camera and extension tubes, but the ease of doing it with my digital camera removed all the constraints. The aerial imagery was a new opening entirely. So, jumping into the digital world indeed opened up new avenues to me. I still consider my 4×5 film camera—I’m now using it exclusively for black-and-white film—to be my primary camera, but I can truly say that my digital camera is the best “second camera” I’ve ever enjoyed. I can also attest to the fact that I’m a bit more willing to try some “crazy new things” digitally than I was with the film cameras (though I’ve done a lot of “crazy new things” with film cameras), but it’s tempered by more than 40 years of looking carefully before shooting to judge if some of those new ideas are just too ridiculous. Yet, when I judge the idea to be worthwhile, I feel far more freedom to explore it more widely with multiple images, with the thought of later editing out the poor ones and choosing the best as “keepers.” In this case, the idea of “pixels are free” has real merit (figure 17-1: compare this with figure 14-2c).

All of us want to be successful. All of us want to avoid failure. (These are two different things, so the previous sentences are not redundant.) Sometimes photographers seem almost terrified to try something new for fear that it may fail. I have seen this syndrome for years hidden within questions I’m asked during workshops, at lectures or gallery openings, or in casual discussions with both amateur and professional photographers. We can all get caught in such hang-ups, myself included, although I consciously try to avoid that type of hesitancy. But I suggest that if you want to know every result before you plunge ahead, you can’t achieve an “aha!” moment that lifts you from the banality of everyday plodding (i.e., neither success nor failure, but just getting by) to something much more exciting, enlivening, and satisfying. The possibility of abject failure is the price you must be willing to pay for trying something new, something different, something removed from your normal procedures. (Initially this may appear to be contradictory to thoughts on previsualization in the early chapters, but it isn’t. Read on.)

Digital photography can be helpful here, for you can try something, decide it’s an abject failure, and delete it on the spot or later. Under these circumstances “pixels are free” is a huge asset. But even here, you can fool yourself, confusing something that is simply “different” with something that is truly worthwhile.

My advice is to loosen up. Don’t plunge ahead foolishly by trying something with no knowledge or insight or feeling of curiosity, but plunge ahead nonetheless. (In other words, don’t waste your time trying things that basically seem useless or silly just to try something, but go ahead with the new idea if it seems truly intriguing to you . . . even if you have no assurance of success.) Most of all, be willing to experiment with new tools, new subject matter, new ways of seeing and composing, new ways of interpreting the scene, and a new and different black-and-white or color palette. Let your intuition take over if it seems to be leading you to something different, perhaps something you’ve never tried before.

Intuition in Science

It turns out that many great scientific advances did not proceed through methods that most people would consider to be scientific. Rather, these advances were intuitive at the outset. Certainly this is true of two of the greatest advances in 20th century physics: Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity (actually two successive theories, the special theory of relativity and then, ten years later, the general theory of relativity, with the latter building upon and extending the former) and Richard Feynman’s theory of quantum electrodynamics (QED).

Einstein asked himself, “What would I see if I were traveling through space at the speed of light, or approaching the speed of light?” He proceeded with a series of thought experiments, ultimately arriving at his conclusions. Thus he used both intuition and existing scientific literature to build up his concepts and eventually his complete theory. But his initial thinking was purely intuitive, as were many of the insights along the way. Previous scientific discoveries—primarily Maxwell’s equations for electromagnetism—were relied upon for the basic foundation and confirmation of his theory, but the original thinking was intuitive.

Years later, Feynman did a similar thing in co-creating the theory of quantum electrodynamics (QED). Working alone, he created a series of drawings, known as the Feynman Diagrams, to describe what others were attempting to understand mathematically. His diagrams are still used today (and have been expanded to other fields) to gain insight and explain phenomena that are almost inconceivably difficult to convey any other way. Feynman effectively used art to explain science.

It may come as a real shock that the greatest advances in physics (the hardest of hard sciences) started from intuitive insights, not from purely mathematical or scientific concepts. But it’s true! Scientists often pursue an idea because it feels right to them, so they follow their instincts and uncover extraordinary new truths. Sometimes they’re wrong, as in the case of two-time Nobel laureate Linus Pauling, who hypothesized a single helix form of DNA before James Watson and Francis Crick showed it to be a double helix.

Avoiding Intuition

Photographers (if my own experiences and observations are correct) seem decidedly averse to following their intuition and trying out new ideas, new methods, or new approaches. This is an obstacle that photographers must force themselves to overcome. Avoiding your own instincts in any aspect of photography—seeing, postprocessing, developing, optimizing, printing, etc.—is deadly. It boxes you in. It prevents you from spreading your wings and flying. Even a bird has to start flying. There’s a time in the life of every bird when it jumps off the edge of its nest or the edge of a cliff and opens its wings for the first time. It’s intuitive. It’s instinctual. But it’s the first time . . . and it better work! There’s no second chance.

Now, think of the other arts such as painting, sculpting, writing, or composing. How much testing is done? How long do painters spend testing things before they proceed with their work? How could Michelangelo test his slab of marble before producing David? How could Shakespeare or Ibsen or Twain or Tolstoy “test” what they were writing—or planning to write—without just sitting down and putting the pen to the paper? Beethoven or Brahms or Rachmaninoff may have played a few bars on the piano while composing, but that doesn’t give a huge amount of insight into an orchestral piece scored for dozens of woodwind, string, brass, and percussion instruments. These artists simply had to proceed with what they were doing. They didn’t—perhaps couldn’t—get sidetracked by testing.

But too many traditional film/darkroom photographers get hung up on testing, and too many digital photographers get too hung up on measuring . . . measuring everything. Does it make them better photographers? Rarely, if ever! In fact, it’s like hanging a boulder around your neck. It drags you down. It sidetracks you from what’s really important: personal expression, insight, involvement, and excitement with what you see and what you want to say.

![]() Photographers seem decidedly averse to following their own intuition and trying new ideas, new methods, or new approaches.

Photographers seem decidedly averse to following their own intuition and trying new ideas, new methods, or new approaches.

Even a bird has to start flying. There’s a time in the life of every bird when it jumps off the edge of its nest or the edge of a cliff and opens its wings for the first time. It’s intuitive. It’s instinctual. But it’s the first time . . . and it better work! There’s no second chance.

Understanding and Misunderstanding Intuition

Perhaps the real problem that prevents people from relying on their intuition is a misunderstanding of what intuition really means. When Einstein started to think about gravity, and what ultimately became the theory of relativity, he had some real insights into the issue. The same applies to Feynman when he created his diagrams as a way of explaining deeply vexing problems. Both scientists were fully immersed in the field, understood what was being considered, and were fully aware of scientific understandings to that point. In other words, because they were deeply involved in the issues they were probing, they were able to proceed by applying intelligent “gut feelings” to their own research, allowing them to go where nobody had ever gone before.

Unfortunately, some people think that intuition is something that’s hanging in the air, like magic. That’s not what intuition is. Einstein and Feynman basically prove that point. For both of them, and for everyone else, intuition comes from deep personal interest and involvement, as well as a high degree of knowledge and experience.

My dictionary defines intuition as “the immediate knowing or learning of something without the conscious use of reason; instantaneous apprehension.” Intuition is not only an immediate thing, but it comes from a great understanding of closely related or analogous issues. Intuition surfaces when you’re familiar with and deeply involved with the situation at hand. It occurs when you have already given a lot of thought to the subject, so much so that it’s really a part of you. You can’t have intuitive notions about something you don’t know, something that’s foreign to you, or something with which you’ve had little prior interaction.

In photography, this translates into a true bond between you and the subject matter you photograph. It’s the same in all other fields. As I pointed out in chapter 1, if you asked a noted orator like Martin Luther King, Jr. or Winston Churchill to make a speech on quilting, he would fail because he had no interest or insight into that issue. But in their areas of expertise, King or Churchill would knock your socks off with rhetoric and insight. The moral of the story is, you’ve got to be deeply involved and interested in the things you’re photographing, and you’ve got to have some basic feel for how you want to depict them.

Beyond that, you need a deep respect for what you’re photographing. Without that respect, something is lacking, and believe it or not, your audience can see right through it. I photograph landscapes because I feel a very close kinship with nature. Furthermore, I’m frustrated by the way humanity is destroying nature on the only planet we’ll ever have to support us. That explains why I’ve photographed things like clearcut forests (see figure 1-1)—not because I respect the clearcut, but because I respect nature so much that I need to show how destructive mankind can be. It is my (largely futile) attempt to try to change our ways.

The greatest portraitists deeply respect the people they choose to photograph. By putting their respect together with their lighting and compositional skills, they produce insightful portraits of their subjects. Intuitively, you know what turns you on—the things that you’re drawn to, that you respect, and that you work with best.

In the darkroom or at the computer screen, you need a basic idea of the image you want to create and some knowledge of the methods you’re using to get to that goal. You can’t make a final image if you don’t know the processes involved, but you can’t waste your time testing everything before you apply your knowledge and make the final image.

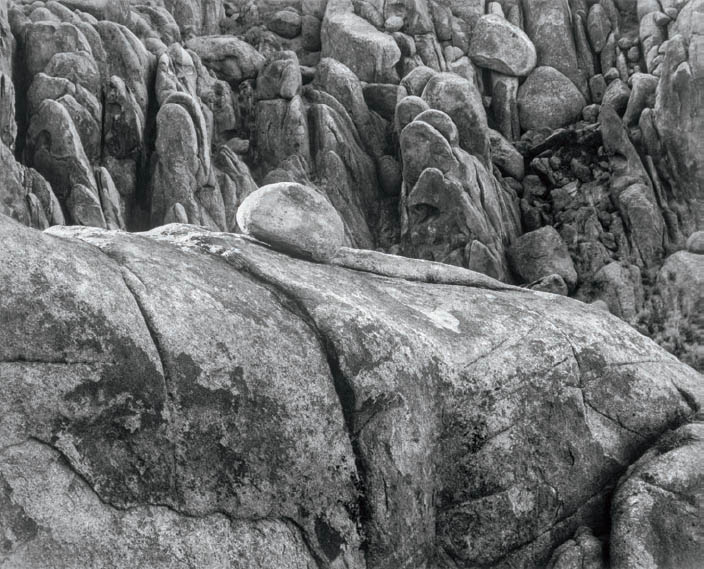

Figure 17-2: Alabama Hills Bread Loaf

In the 1970s, I began photographing the boulder fields below Mt. Whitney known as the Alabama Hills. I was attracted to the seemingly inexhaustible piles of boulders, heaped on top of one another in endless varieties of forms. Over the years, I made dozens—perhaps hundreds—of photographs of this bizarre area, and I am still attracted to the weathered granite boulders that seem to be the remains of the creation of the earth. In this image, the isolated large boulder sitting atop vastly larger ones, with a wall of more vertical boulders behind, looked like a huge sourdough bread loaf to me.

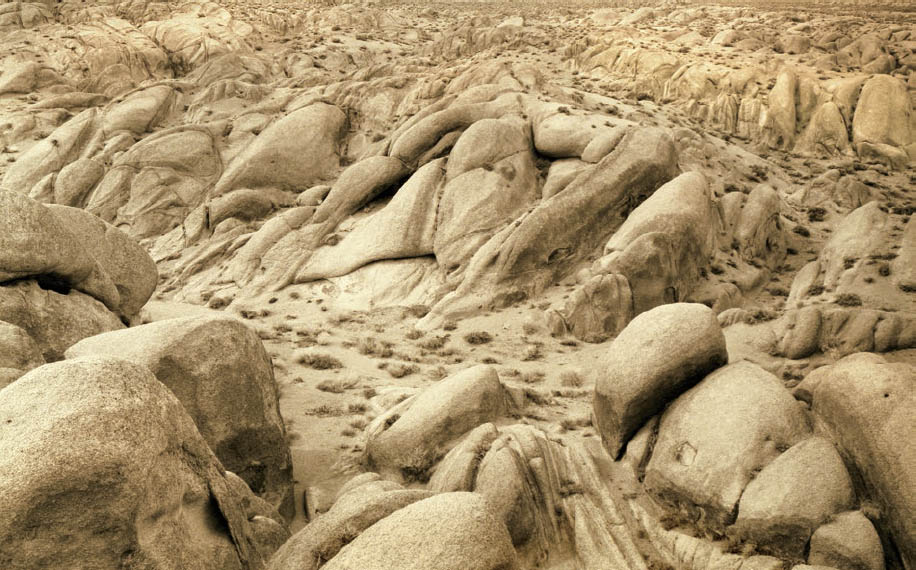

Figure 17-3: Fields, Alabama Hills (photograph courtesy of Reed Thomas)

Reed Thomas was also attracted to the Alabama Hills, but he interpreted the area in a completely different way. While I was drawn to the boulders in bold, contrasty images, Reed was drawn to the fields with quiet, subtle midtones. The differences were made even more evident as Reed applied a light sepia-type toning to his images (compare figure 17-2). Both visions were deeply felt. Both are truthful and valid. Both say something personal about the area.

Examples of the Intuitive Approach

In 1986, I co-instructed a workshop with Reed Thomas. Prior to that workshop, Reed and I spent several weekends photographing together in the Alabama Hills, the immense rock-strewn landscape below Mt. Whitney in the Sierra Nevada. Prior to that, each of us had photographed that area individually and extensively over several years. My photographs were dominated by deep tonalities and bright highlights, while Reed’s were characterized by softer contrasts and lighter tonalities. I focused on the boulders themselves, while Reed focused on the vast fields of boulders, seemingly spreading forever (figures 17-2 and 17-3).

Reed and I decided to open the workshop in an unusual way: we each placed 10 of our photographs in a stack and then simultaneously showed them one at a time. By the time we got to the eighth print, one of the students cried out, “OK, I see how Bruce sees this place and I see how Reed sees this place, but what does it really look like?” That was the perfect question. To me, it looked like my images; to Reed, it looked like his. Both were valid interpretations. Both were correct. Yet they were strikingly different. Each of us had our own vision, and we both followed our vision—our intuition. In essence, as we walked through the boulder fields I photographed the boulders; Reed photographed the fields. Inevitably, the students would have to see how the Alabama Hills looked through their own eyes.

The key idea here is that both Reed and I had a very definite vision of how we saw the region. Both of us were deeply involved, deeply interested in the place. It’s a truly awesome area. We would walk together at times, and diverge in different directions at other times, each of us pursuing our own personal vision. Each of our photographs was consistent with the others we produced. Neither of us forced our vision. It was simply how we each saw that landscape.

Figure 17-4: Birch and Bracken, Glen Affric

While scouting for a workshop in Scotland in 1998, I came across this scene, looking steeply downhill through a forest of birch trees and a floor of dense bracken ferns. On a brightly lit day with thin, high, overcast skies I saw the nearly white tree trunks and ferns as overwhelmingly luminous. Placing the average reading in Zone 7 (very light gray), I photographed the lovely scene as I envisioned it, thinking that everyone would see it that way. Evidently not. A close friend standing beside me when I made the photograph was utterly astounded by the light tonalities when he saw the final print a year later, unable to determine what I had done to achieve it.

On another occasion, while scouting for a workshop in northern Scotland, I was in the beautiful valley of Glen Affric. Looking from a hillside into a forest of birch trees and tall bracken ferns, I set up my camera. The scene appeared bright and airy to me, and I wanted to convey that feeling. Ian Biggar, a good friend who had assisted me on several previous workshops, was with me when I stopped to take that picture and he looked through the camera when I composed the image. So he not only saw the same scene, he saw my exact composition.

A year later, during the workshop, and after the group had spent a day in Glen Affric, I showed that photograph (figure 17-4). Ian leapt out of his seat (quite literally!) asking, “How did you do that?” I looked at him blankly, failing to comprehend the question. After all, he had already seen the composition in the field. What was it that he was asking? I was clueless. It turned out that the tonalities of my image surprised him. I had instinctively made the exposure by exposing the average tonality at Zone 7, quite high on the scale. I did so without thinking much about it. Everything looked bright and airy to me. I would have guessed that everyone would have seen it that way, since it was intuitive to me! In my mind it was not just the obvious way to see it; it was the only way.

Ian apparently saw the scene as an average Zone 5. So in his mind, the image would have been much darker. I finally understood his confusion when he asked if I had used infrared film. I hadn’t. The negative was exposed on Kodak Tri-X panchromatic film. Infrared tends to lighten foliage, especially foliage in sunlight. I realized that the creative aspect of this photograph was my initial intuitive seeing of the scene as quite bright. Ian’s question about infrared cleared things up for me; he was simply surprised by how bright the image was.

Most people see forests—even birch forests with near-white trunks—as midtoned or dark-toned places. I tend to see forests as luminous places. I am influenced by my love of forests. I live in a forest of large, tall conifer trees in Washington State, and I revel in its light.

So the intuition, the creativity, the insight was in my seeing the forest as bright and glowing, not dark. This could only have come from a deep interest in such natural areas, despite the fact that I had never previously been to this particular area. Intuition doesn’t come out of nothing. It needs deep involvement, interest, and understanding to gain a foothold.

My deepest and strongest involvement leading to intuitive insight was my reaction upon first entering Antelope Canyon (the first slit canyon I ever encountered), which I instantly saw as force fields rather than eroded sandstone walls. It wasn’t something I thought about and concluded; it hit me spontaneously and instantly. No thinking was involved. It was an immediate reaction, like ducking away from a ball coming at your head. The only difference between the two was that my reaction to the canyons came out of my lifelong interest in physics.

This, I believe, is where most people misinterpret the concept of intuition. My reaction stemmed from a lifelong fascination with, and education in, physics. Without that background I could not have reacted to the canyons the way I did. But my response was immediate, virtually devoid of thinking. And it was devoid of thinking because the thinking was already ingrained. It was a part of me.

Some people are intuitive in understanding and “reading” others. Most of us are not very good at it. Those who are good at it have probably been (consciously or subconsciously) students of human behavior all their lives. They are deeply interested in how people respond to a variety of circumstances, they observe people in unusual detail, and in time they intuitively recognize how people will respond to new circumstances. Such people don’t gain their insights out of nowhere, but rather from years or decades of carefully observing human behavior. In time, they become experts at it.

Applying Intuition to Your Photography

The idea of using intuition that I’m considering here has something to do with photography, but much more to do with life . . . your life. You likely have a deep interest in many things. In fact, you’re undoubtedly quite knowledgeable about many subjects. You may even have reached the expert level in some things without even realizing it, and you might not accept that as fact even if it were pointed out to you.

Everyone has deep insight into something. So, ask yourself, “What do I understand and respond to best?” Are they things in and around your home? Is it the people you meet? Is it sports? Is it landscapes, those nearby or far away? Is it flowers or the insects that visit the flowers? It can be any of a million things, but whatever it is, those are likely to be the things you truly know most intimately, and that is the subject matter you can photograph most effectively.

What I’m suggesting here is to apply your lifelong interests to your photographic seeing, especially if those interests have a visual component. I had a lifelong interest in physics and saw its visual component in Antelope Canyon, though I was surely not an expert in physics. Certainly I was not in the class of Einstein or Feynman when I instantly related Antelope Canyon to force fields. I recommend you apply your own lifelong interests, knowledge, and expertise to photography whenever possible. You may not be able to plan that, just as I couldn’t have planned applying insights in physics to a place like Antelope Canyon. You can’t know in advance exactly how the process will work, and that’s OK. I didn’t plan my photograph of the birch forest in Glen Affric; I just did it when I saw it! Nor did Reed and I plan our photographs of the Alabama Hills. Instead, we each just did it!

Follow your gut feelings about how you want to photograph and interpret subject matter. Too often photographers are so unsure of themselves that they’ll point to something and ask, “Is that Zone 4?” or “Is that low on the histogram?” Of course nothing has a zone number on it or a selected location on the histogram. It’s whatever you want it to be! But the question shows both uncertainty and a desire to see the scene, photograph it, and print it in some standard, acceptable way—a “politically correct” way. That approach overrides intuition. It’s walking away from your own gut feelings, from your own real goals.

When Einstein developed the theory of relativity, he didn’t do reality checks with other physicists asking, “Does this make sense to you?” He plowed ahead. Feynman didn’t ask if his silly pictures made any sense to others as he refined his ideas that led to QED. He plowed ahead. I didn’t ask if seeing Antelope Canyon as a force field made any sense to others. I plowed ahead. This is a critical thing to recognize: you can’t force intuition. It happens when it happens. Before entering Antelope Canyon I couldn’t tell myself to go out and find Antelope Canyon so I could apply my lifelong interest in physics to it. But the instant I walked into it, the ideas from my physics background tumbled into my head. I went with those thoughts.

![]() This is a critical thing to recognize: you can’t force intuition. It happens when it happens.

This is a critical thing to recognize: you can’t force intuition. It happens when it happens.

There’s a lesson here. I didn’t second-guess my instantaneous, intuitive thoughts. I didn’t run away from them or try to suppress them. I didn’t say, “But this doesn’t tell you what Antelope Canyon looks like.” Nor did I ask, “How does this fit into the work I’ve already done?” And I certainly didn’t ask the deadliest of all questions: “Can this photograph sell?” If you’re going to do anything of real value, you have to please yourself, not consider if it’s pleasing to others. In fact, none of that mattered to me. None of that even entered my mind. I was using the shapes of the canyon walls to express my thoughts about something completely different: forces in nature (see figures 3-6 and 9-3). That became my guiding principle. Using the forms in that canyon as surrogates to express my thoughts about forces in nature was the overriding goal for my initial imagery, and those thoughts applied to all my subsequent slit canyon images. I’ve never found such forms in any other subject matter I’ve encountered, restricting that intuition to those narrow clefts alone.

Too many people encounter something that sparks their intuition, but since they literally fear those thoughts, they actively suppress them. They want to be sure they’re not doing something weird, bizarre, way out, or just downright silly. Well, any of those may be true. That’s the chance you have to take. But if it makes sense to you, I urge you to roll with the flow and do it!

Einstein and Feynman had a deep understanding of physics, so their intuitive notions made sense to them. Just as my interest in physics made my interpretation of the slit canyons sensible to me, you can draw on your interest and knowledge of things you’ve observed all your life for your best imagery. Use that understanding to lead your own vision.

Of course, as your knowledge and experience of photography grows, you have progressively more to draw upon to marshal your intuitive ideas through to the final image. For example, my knowledge of reducing contrast in a scene through compensating development gave me the technical tools to carry my vision through in Antelope Canyon. That technical knowledge was new to me at the time. But I needed no new photographic knowledge to see the birches in Glen Affric as I did, or to see the boulders of the Alabama Hills as I did.

With increased photographic knowledge, you can be looser in your field work as well as your darkroom or computer work. You get so comfortable with it that you can give yourself the freedom of altering your usual methods when necessary to create a different result. In time, such decisions also become intuitive because you quickly recognize when standard methods will fail to yield the results you want.

No matter what your level of knowledge is, you can do a lot right now! You will be able to do more in the future as your knowledge grows, but you can still tap into your intuition now. You can, and must, apply your intuition borne of your lifelong interests to do photography in your own unique manner. If you don’t, you’re shortchanging yourself and depriving the world of your photographic insights.

Conclusion

First, let’s see how these thoughts mesh with the ideas of previsualization expressed early in the book. I believe you should previsualize the final image to the greatest extent possible while you’re standing behind the camera, but also that you should give yourself the freedom to see it your way rather than anyone else’s way. The ideas expressed here explicitly ask you to follow your own vision and your own intuition, rather than worry about others seeing it your way (or you seeing it their way). They may see it your way. They may not. That’s their problem, not yours. Follow your instincts, your vision, and your intuition of how the scene should be photographed and interpreted. These thoughts reinforce the earlier ideas about previsualization.

The bottom line is this: Know yourself and your interests. This is more difficult than it sounds because we tend to misread ourselves. Too often we overrate or underrate ourselves, or we just fail to understand our own interests properly. Beyond that, we tend to doubt our own intuition, our own vision. We’re afraid to rely on it or use it. We may even think it’s wrong to be intuitive. It isn’t. Don’t run away from your strongest intuitive notions: They’re likely to be valid. You’ve got to be bold enough to take the risk.

So, although you can’t force intuition, don’t deny it when it strikes. Once you get a handle on your own interests—and along with them, your areas of expertise—you can confidently apply your intuition and understandings far more effectively to all things photographic, from the initial seeing to the finished product, and also to the methods used along the way.

When all is done, try to take a step back and view your work as a dispassionate observer. Ask yourself if your work still communicates with you. Be prepared (and willing) to make some adjustments.