–( FOUR )–

Creating Brave, Psychologically Safe Spaces

What if we first created brave spaces so that more people could feel safe speaking their truths?

In the introduction I shared an example of a situation where a leader asked me how he might have been brave in the moment. In a meeting where participants were encouraged to share their personal diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) journeys, he shared a time when he upset an LGBTQ employee by mistakenly using the wrong terminology to refer to them (the employee’s preferred pronoun). His purpose for sharing this situation was to illustrate that we will make mistakes and can recover from them if we are willing to acknowledge and learn from them. As he was sharing the story, several in the audience of about three hundred snickered and laughed. Although this leader was not sure what sparked laughter, it made him feel very uncomfortable. He thought perhaps the laughter was targeted at the particular reference to LGBTQ community.

While the appropriate approach depends on a number of variables, if the condition of brave, psychologically safe space exists in the organization, I advised him to share how the laughter made him feel using an “I” statement. He might say something like: “While I don’t know what promoted the laughter, and in the spirit of bravery, I want to share the impact. It made me feel uncomfortable because I was sharing a serious, deeply personal example of how to recover from mistakes. I am concerned how the laughter might be interpreted by others. I want to be sure we are fostering inclusion and belonging and to be able to continue to have open conversations on difficult topics.”

This approach comes with risks. In a perfect world of brave spaces, the risks are lower. However, in the imperfect world that most of us exist in, we have to consider the risks and other conditions for inclusive conversations such as the power dynamics discussed in Chapter 5. In this scenario the person sharing the story is a leader and therefore his position afforded him the positional power to call out the behavior. If you are not in a position of power, in a brave space organization, we would hope that someone in power would call out the behavior. If that does not happen, it may be safer to share the impact with your manager, mentor, or human resources representative expecting that they would take action to communicate the impact to all in attendance.

From Safety to Bravery

Inclusive conversations push the boundaries of safety to bravery. Creating brave zones is a condition that allows for the surfacing and sharing of each other’s deep truths without fear of retribution. It is a space where it is expected that there may be discomfort, where you might feel some anxiety, ambiguity, and even discord as opposing perspectives are shared. It is also a space where you feel safe enough to be brave, to push the boundaries of political correctness and obligatory, unchallenging small talk.

Safety often means something different for dominant groups than it does for subordinated groups in inclusive conversations. For dominant groups, when discussing race in particular, “safety” more often means that “you will not make me feel uncomfortable.” For groups that have been historically marginalized, “safety” often means that “I can make you feel uncomfortable (even if that is not necessarily my intention) and you will listen without defensiveness, dismissiveness, and whitesplaining” (a concept defined in Chapter 10).

Dominant groups in an organizational and societal context set the rules and therefore rarely move beyond safety as defined by those groups. For subordinated groups, experience has taught them that if you name the reality of your experiences of oppression, exclusion, and a sense of not belonging, you risk being labeled as overly sensitive or misguided. Conversation either shuts down completely or it reverts to less meaningful “safe” topics. Relationships may be damaged or completely ruined. In either case, inclusive conversations are no longer possible nor is the condition of psychological safety.

Psychological Safety

“Psychological safety” is defined as the belief that you will not be punished if you make a mistake.1 Psychological safety describes individuals’ perceptions about the consequences of interpersonal risks in their environment.2 People who are psychologically safe feel free to speak up about problems and sensitive issues. One’s perception of psychological safety is based on a belief about the group norm. If the norm in the culture is that we can talk about uncomfortable topics, that we are open to hearing opposing views, the condition of psychological safety is likely present.

How do you know if your environment is psychologically safe? Some of the ways to assess psychological safety are offered by researcher A. Edmondson in the article “Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams.”3 Are the following conditions present in your organization or workplace?

![]() When someone makes a mistake, it is often held against them.

When someone makes a mistake, it is often held against them.

![]() In this team it is easy to discuss difficult issues and problems.

In this team it is easy to discuss difficult issues and problems.

![]() In this team people are sometimes rejected for being different.

In this team people are sometimes rejected for being different.

![]() It is completely safe to take a risk on this team.

It is completely safe to take a risk on this team.

![]() It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help.

It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help.

![]() Members of this team value and respect each other’s contributions.

Members of this team value and respect each other’s contributions.

Creating Brave Spaces First

The typical narrative is that people have to first feel safe before they can be brave. But what if the order was the opposite? What if we create spaces where people can be brave so that we can all eventually feel safe? I am not suggesting that people, particularly those from historically marginalized groups, have to risk being misunderstood, ridiculed, or otherwise outed for people to feel safe. However, I am suggesting that until we address the roots of psychological danger (the opposite of psychological safety)—exclusive mind-sets and policies—by creating spaces in which everyone is encouraged to delve into their own discomfort and learn about who they are, who others are, and how we can be bridges for one another, we will not be able to create sustainably safe places.

If we use that definition of bravery, it could be considered brave to ask questions of yourself—about your identity, your culture, your biases, as outlined in Chapter 3. It could be brave to explore how you relate to your cultural “others” and how you are able, or unable, to bridge gaps in cultural understanding. It could be brave to simply have conversations with those whose views are different from yours and to be inclusive of those views (unless those ideas are harmful to you or anyone else). It could be brave to delve into some of the ways in which you have been marginalized (or have marginalized others) and to see those instances against the backdrop of inequitable systems.

If this is bravery, then bravery leads to safety. Once you’ve been able to share deeply about who you are and what you believe in, even with those you’d never thought you would agree with, perhaps you’ll see that the possibilities for human connection go beyond what you could have imagined in this polarized world. In the end, the conversation about safe spaces should not be a battle between those who feel safe and those who don’t. Rather, it should be a conversation about how we can all benefit from being brave enough to be who we are and see the person across from us in all of who they want to be. Ultimately, we will all feel safer when we are no longer strangers to ourselves and to each other.

Are We Ready for Psychologically Safe and Brave Conversations?

Many of our environments are just not ready for brave conversations about race, ethnicity, religion, gender, and other dimensions of difference, and to push it too soon is to regress from any progress made. As I discussed at length in We Can’t Talk about That at Work, getting to inclusive conversations is a developmental process that requires meeting people where they are. Those of us who are activists and practitioners in the DEI space can get very frustrated with our colleagues who don’t want to have the tough conversations. I contend that for many they just don’t know how and will retreat into a noncommunicative, unhealthy place—obviously not the desired outcome. We cannot just will brave spaces because we want them.

If we jump right into brave spaces without the conditions discussed in Chapter 2, we run the risk of disrupting long-held beliefs in ways that shock the system. Often the conversation space is limited to a two- to four-hour onetime session limiting the opportunity to develop trust and brave spaces. Both dominant and subordinated groups might leave such sessions feeling traumatized. That trauma may play out as shock and denial as described in Chapter 6 for dominant groups, and for subordinated groups it may just deepen and/or open already painful wounds. Inclusive conversation sessions have to be structured in ways that acknowledge the pain and offer some type of follow-up to address the potential trauma.

The book The Art of Effective Facilitation has a chapter called “From Safe Spaces to Brave Spaces: A New Way to Frame Dialogue around Diversity and Social Justice.”4 The authors share an experience with a group of college students training to be resident assistants in college dorms. They facilitated a popular experiential exercise designed to help participants understand privilege, a concept defined in Chapter 5. The exercise calls for the group to form a line. The facilitator then shares a series of statements and if the statement pertains to you, you step forward, if not you step back. Some sample statements include:

![]() If your ancestors were forced to come to the United States not by choice, take one step back.

If your ancestors were forced to come to the United States not by choice, take one step back.

![]() If your primary ethnic identity is “American,” take one step forward.

If your primary ethnic identity is “American,” take one step forward.

![]() If you were ever called names because of your race, class, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation, take one step back.

If you were ever called names because of your race, class, ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation, take one step back.

![]() If there were people who worked for your family as servants, gardeners, nannies, and so on, take one step forward.

If there were people who worked for your family as servants, gardeners, nannies, and so on, take one step forward.

![]() If you were ever ashamed or embarrassed by your clothes, house, car, and so on, take one step back.

If you were ever ashamed or embarrassed by your clothes, house, car, and so on, take one step back.

![]() If one or both of your parents were “white collar” professionals (doctors, lawyers, etc.), take one step forward.

If one or both of your parents were “white collar” professionals (doctors, lawyers, etc.), take one step forward.

Usually participants who hold dominant group identities finish the exercise in the front of the room, and those of subordinated group identities in the back. To the facilitators’ surprise and dismay, the exercise did not go well. Students who held dominant group identities felt “persecuted, blamed and negatively judged.” Subordinated students said the exercise was a painful reminder of their daily lived experiences. They also said that it put them in the role of teaching their dominant group colleagues about their different experiences, which is exhausting. This is a prime example of lack of readiness to have inclusive conversations. Without having first conducted foundational education to build skills in self-understanding and understanding others, these types of exercises can do more harm than good and shut down meaningful dialogue.

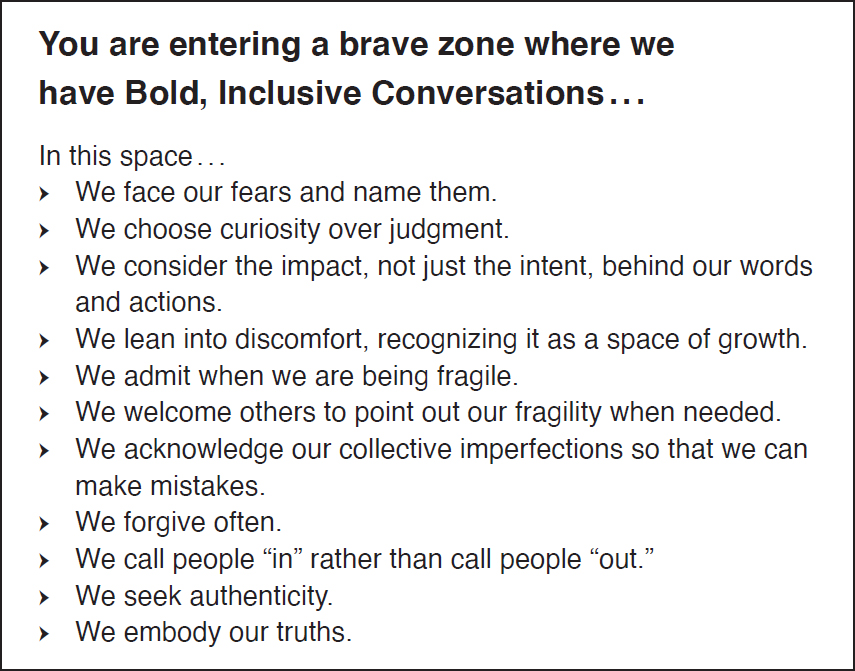

FIGURE 4.1 Conditions for a Brave Zone

Source: The Winters Group, Inc.

In Figure 4.1, The Winters Group has developed some conditions that are designed to create brave spaces for inclusive conversations. However, we use them only with advanced groups who have some competency in diversity, equity, and inclusion concepts and who we feel are ready to embrace them. I discuss fear, fragility, and forgiveness as well as calling people in rather than out in later chapters.

Who Doesn’t Enjoy Psychological Safety to Speak Up?

These days employees are encouraged to bring their whole selves to work. Leaders have learned that employees will be more productive and engaged to the extent that they feel that they can be authentic, openly sharing their feelings and nonwork-related aspects of who they are. Although this might sound like a great way to foster psychological safety and brave spaces for dialogue, for those in subordinated groups this is often a joke. I have heard many people of color laugh and say, “Are you kidding me? They could not handle my whole self. I can bring only the self that is most like the dominant group.” People with nonvisible disabilities may not want to share that aspect of their identity, fearing that it could limit their career opportunities. In the 2016 Fortune article, “An Inside Look at What’s Keeping Black Men out of the Executive Suite,” research shows that Black men report that they have to constantly code-shift (explained in Chapter 9), needing to appear “focused in the office but not too aggressive, hungry but not too threating, well-dressed but not showy, talented but not too talented.”5 The energy expended not bringing your full self to work can be exhausting.

In a study conducted by David Hekman and colleagues, published in the journal of the Academy of Management in 2016, they found clear and consistent evidence that women and people of color who promote diversity are penalized in terms of how others perceive their competence and effectiveness.6 The researchers interviewed 350 executives on several diversity-valuing behaviors—for example, whether they respected cultural, religious, gender, and racial differences; valued working with a diverse group of people; and felt comfortable managing people from different racial or cultural backgrounds. They defined “diversity-valuing behavior” as that which promotes demographic balance within organizations. Their conclusion was that when white men vocally valued diversity, they were not rated less competent, but women and people of color who advocated for diversity were. Women and people of color are more apt to come under attack when they speak out for those in their identity group, in a way that white men are not.7

A study by the National Bureau of Economic research showed that Black people have to perform better than their white counterparts.8 The study found that Black workers are more closely scrutinized, which increases the chances of errors being caught, and the result is that Black workers were more likely to be let go for “errors,” thereby making it less safe to make a mistake. Many LGBTQ employees still do not feel safe bringing their whole selves to work. According to research by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, 46 percent of LGBTQ employees are not open about their sexuality at work for fear of being stereotyped, making people feel uncomfortable, or losing connections with co-workers—a statistic that has not changed much since 2008.9

Women are more often labeled as having an “aggressive” communication style. A 2019 study reported in the Harvard Business Review looked at two hundred performance reviews from one company. The study counted the number of references to being “too aggressive” in the reviews and found that 76 percent of the instances of aggressiveness were attributed to women, while only 24 percent of men were identified as having such a communication style.10 This type of feedback leads to women questioning themselves and perhaps not speaking up as much. Those in dominant groups may not feel safe to discuss issues faced by historically subordinated groups. As was the case with the students mentioned above who experienced the privilege walk exercise, they may feel guilt, judgment, and apprehension, which might shut down inclusive conversations.

While organizations have good intentions when they declare their desire for employees to bring their whole selves to work and to create psychologically safe environments, it is not easy and currently not a reality for many historically subordinated groups. It is just too risky to be yourself or to speak up about the inequities that you experience and witness. Dominant groups also stay silent fearing retribution for unintentionally saying something offensive.

Creating Brave and Psychologically Safe Spaces for Inclusive Conversations

Creating and sustaining psychologically safe spaces where inclusive conversations can occur in the workplace takes time, consistency, and intentionality. Here are some specific ways to foster and develop these conditions:

![]() Develop group norms and create shared meaning. What do we mean by “safe spaces” or “brave spaces”? What are specific examples (see Figure 4.1 for Brave Zone conditions)? What are the boundaries? Hold inclusive conversation sessions to brainstorm and gain clarity on these definitions. Start each conversation reminding the parties of the norms. Redefine terms as needed. If these norms had existed in the example at the beginning of the chapter, calling out the laughter might have been easier for the organization leader.

Develop group norms and create shared meaning. What do we mean by “safe spaces” or “brave spaces”? What are specific examples (see Figure 4.1 for Brave Zone conditions)? What are the boundaries? Hold inclusive conversation sessions to brainstorm and gain clarity on these definitions. Start each conversation reminding the parties of the norms. Redefine terms as needed. If these norms had existed in the example at the beginning of the chapter, calling out the laughter might have been easier for the organization leader.

![]() Acknowledge that the extent to which safety and bravery are experienced varies by identity group.

Acknowledge that the extent to which safety and bravery are experienced varies by identity group.

![]() Learn about and discuss the historical, systemic inequities that continue to create unsafe environments for some groups.

Learn about and discuss the historical, systemic inequities that continue to create unsafe environments for some groups.

![]() Listen to and validate the experiences of different identity groups. If you are a leader, make sharing experiences a regular agenda item to build trust and thus encourage bravery. It may take time to break down barriers to get to safe and brave spaces. Be patient. Stick with it.

Listen to and validate the experiences of different identity groups. If you are a leader, make sharing experiences a regular agenda item to build trust and thus encourage bravery. It may take time to break down barriers to get to safe and brave spaces. Be patient. Stick with it.

![]() Pay more attention to and correct biases that perpetuate inequitable environments. For example, if you are a leader with positional power, review each of your performance assessments. Do you use different language to describe the accomplishments of women versus men? People of color versus white employees? Why? Engage in self-reflection as recommended in Chapter 3 to better understand your biases. If you are a member of a historically subordinated group, question feedback that you don’t understand or agree with. Ask for specific examples, like this: “Can you give me a specific instance where I was aggressive? In your mind, how might I have handled that situation in a less aggressive way?” If you don’t agree, you might say something like: “I would like to offer a different interpretation of your example. I am a direct communicator and I was being professionally assertive. Can we talk more about the difference between aggressive and assertiveness? I would like to continue to be effective and also authentic without being offensive or defensive. I don’t want characterizations such as this to impede my progress.”

Pay more attention to and correct biases that perpetuate inequitable environments. For example, if you are a leader with positional power, review each of your performance assessments. Do you use different language to describe the accomplishments of women versus men? People of color versus white employees? Why? Engage in self-reflection as recommended in Chapter 3 to better understand your biases. If you are a member of a historically subordinated group, question feedback that you don’t understand or agree with. Ask for specific examples, like this: “Can you give me a specific instance where I was aggressive? In your mind, how might I have handled that situation in a less aggressive way?” If you don’t agree, you might say something like: “I would like to offer a different interpretation of your example. I am a direct communicator and I was being professionally assertive. Can we talk more about the difference between aggressive and assertiveness? I would like to continue to be effective and also authentic without being offensive or defensive. I don’t want characterizations such as this to impede my progress.”

![]() Become an ally for subordinated groups. A heterosexual, cisgender woman could be an ally for a LGBTQ colleague. The Anti-Oppression Network defines “allyship” as a lifelong process of building relationships based on trust, consistency, and accountability with marginalized individuals and groups of people.11 It is not self-defined—our work must be recognized by the people we seek to ally ourselves with. Becoming a good ally is more than being interested in and passionate about equity, it requires really understanding how the inequities manifest for the group. A good ally will speak up and speak out for the subordinated identity in ways that are empathic and foster a sense of belonging.

Become an ally for subordinated groups. A heterosexual, cisgender woman could be an ally for a LGBTQ colleague. The Anti-Oppression Network defines “allyship” as a lifelong process of building relationships based on trust, consistency, and accountability with marginalized individuals and groups of people.11 It is not self-defined—our work must be recognized by the people we seek to ally ourselves with. Becoming a good ally is more than being interested in and passionate about equity, it requires really understanding how the inequities manifest for the group. A good ally will speak up and speak out for the subordinated identity in ways that are empathic and foster a sense of belonging.

Creating Psychologically Safe Spaces for Children

As pointed out earlier, according to a study by NPR’s Sesame Street and the University of Chicago, parents do not talk with their children about human diversity issues. Another study indicated that children start to recognize racial differences as early as six months old. Today, with easy access to some of the harsh realities of the world through social media and other technological advances, it is not possible nor advisable to shield children. Bullying and suicide rates among young people are at an all-time high.12 Children have to worry about their safety in school. Current realities necessitate that we are intentional about having inclusive conversations with children.

Some specific actions you can take to create psychologically safe spaces for inclusive conversations with children include:

![]() Be honest. When children ask about something that may be difficult, don’t minimize it. Broderick Sawyer, a clinical psychologist featured in Conscious Kid—an education, research, and policy organization dedicated to reducing bias and promoting positive identity development in youth—shared that the first thing you should ask a child who has faced discriminatory behavior is, “How did that make you feel?”13 We must listen with encouragement and without judgment.

Be honest. When children ask about something that may be difficult, don’t minimize it. Broderick Sawyer, a clinical psychologist featured in Conscious Kid—an education, research, and policy organization dedicated to reducing bias and promoting positive identity development in youth—shared that the first thing you should ask a child who has faced discriminatory behavior is, “How did that make you feel?”13 We must listen with encouragement and without judgment.

![]() Consider vocabulary comprehension and experiences. Use words that children will understand at their age level. If you are talking about sexual assault, rather than using an adult word like “assault,” maybe “touching” is a better word coupled with showing the places where children should not be touched. Maybe you develop your own vocabulary for the parts of the body that are off-limits.

Consider vocabulary comprehension and experiences. Use words that children will understand at their age level. If you are talking about sexual assault, rather than using an adult word like “assault,” maybe “touching” is a better word coupled with showing the places where children should not be touched. Maybe you develop your own vocabulary for the parts of the body that are off-limits.

![]() Connect new concepts to ideas or experiences they have encountered previously. Make connections to situations that they will understand, such as “Remember the time when . . .”

Connect new concepts to ideas or experiences they have encountered previously. Make connections to situations that they will understand, such as “Remember the time when . . .”

![]() Be sensitive to age-specific challenges. Start conversations so that children can share in their own words what they are thinking or concerned about. Begin with: “Tell me, what are you thinking about?”

Be sensitive to age-specific challenges. Start conversations so that children can share in their own words what they are thinking or concerned about. Begin with: “Tell me, what are you thinking about?”

![]() Leverage peer-created resources. Find examples of young people talking or writing about diversity-related topics, maybe videos on YouTube that you can talk about.

Leverage peer-created resources. Find examples of young people talking or writing about diversity-related topics, maybe videos on YouTube that you can talk about.

![]() Acknowledge different and even polarizing perspectives. Start with something like: “You may hear people saying . . .” or “Some people believe . . .” and explain that “People care a lot about this and have many different ideas. Sometimes they might lead to arguments.”

Acknowledge different and even polarizing perspectives. Start with something like: “You may hear people saying . . .” or “Some people believe . . .” and explain that “People care a lot about this and have many different ideas. Sometimes they might lead to arguments.”

If we engage our children in inclusive conversations at an early age, it is more likely that they will be better equipped for effective dialogue about differences when they enter the workforce.

SUMMARY

![]() Safe spaces are achieved by first creating brave spaces for inclusive conversations.

Safe spaces are achieved by first creating brave spaces for inclusive conversations.

![]() Brave spaces are not necessarily comfortable. They are designed to take us out of our comfort zones.

Brave spaces are not necessarily comfortable. They are designed to take us out of our comfort zones.

![]() Psychological safety is where people feel free to speak up about problems and even sensitive issues without retribution.

Psychological safety is where people feel free to speak up about problems and even sensitive issues without retribution.

![]() Brave space dialogues may lead to identity-based trauma, which needs to be effectively addressed.

Brave space dialogues may lead to identity-based trauma, which needs to be effectively addressed.

![]() Getting to brave spaces for inclusive conversations takes time and commitment.

Getting to brave spaces for inclusive conversations takes time and commitment.

![]() Research shows that women and people of color are more often penalized for speaking up for inclusion, suggesting that we may not feel safe to do so.

Research shows that women and people of color are more often penalized for speaking up for inclusion, suggesting that we may not feel safe to do so.

![]() Effective allyship is important in creating brave spaces for dialogue.

Effective allyship is important in creating brave spaces for dialogue.

![]() It is important to create psychologically safe space for children to engage in age-appropriate inclusive conversations.

It is important to create psychologically safe space for children to engage in age-appropriate inclusive conversations.

Discussion/Reflection Questions

1. How doe you define safe spaces as contrasted to brave spaces? What is the difference?

2. To what extent is your environment safe for inclusive conversations? Brave? If it is not safe or brave, what needs to be done to create safe and brave spaces?

3. What happens in your environment when someone makes a mistake about diversity, equity, or inclusion issues?

4. How do you become a good ally, as defined in this chapter?

5. Why is it important to engage in brave conversations with children?