5. CREATING THE CONTAINER

Creating the physical and energetic field within which we meet

WHY A CONTAINER?

Creating the Container is about providing an environment for our gathering that is enlivened, has boundaries, and is safe. When the participants of our gathering feel honored as human beings and encircled in safety, authentic engagement can emerge. In order to achieve this, we pay attention to the space, both energetic and physical, in which we will be “held” during the duration of the meeting.

It is important that we prepare both of these spaces, or fields, so that we have an inner and an outer container to hold the gathering.

The inner, or energetic, container provides security and safety so that those within may freely express themselves. The outer, or physical, container reminds us of our humanity and aliveness, and encourages connection.

Selection of venue, size, shape, and what we bring to it are all part of preparing the outer container. This can be done in a physical space or virtually (see “The Virtual Container,” below). Our meeting space will also be defined by the seating pattern, whether rows, theater style, or circle.

In addition to the physical space, the inner, or energetic, container is designed and prepared with an eye to safety within strong boundaries. This is achieved by having terms of engagement, or the protocols and agreements that will be observed for the gathering. The Convener may define these and ask for agreement from all participants. Important protocols and agreements include confidentiality, marking of time, who may speak and when, and how we are to acknowledge or speak to each other.

CHALLENGE

Reluctance to impose our will on others

Strong boundaries, the very nature of a container, established by our protocols and agreements, are essential for safety to be present within the group, and for the emergence of authentic engagement.

The challenge of this Aspect of convening is, ironically, our reluctance to impose our will on others.

This can be a tough and elusive challenge for many people who have been trained or conditioned to be flexible and freewheeling in social interactions and who don’t wish to be perceived as pushy, authoritarian, or rigid. The flip side of not wishing to impose our will is equally challenging. The “my way or the highway” manager may get compliance, but not necessarily respect and an environment of safety when mandating command-and-control rules and regulations.

The expression of our inner authority and confidence as a Convener is crucial, as is our willingness to step forward, and to name and ask for agreement to the terms of engagement.

Without clearly stated agreements and protocols up front, everyone may be left to define his or her own unstated boundaries and conditions for participation, which runs the high risk of dissipating the group’s energy. It then takes energy for each of us to create and hold our own terms of engagement because we don’t know what might be acceptable to the others in the room that might violate our boundaries. Our sense of safety is compromised in an anything-goes environment, and it becomes difficult to engage authentically.

In addition to the courage needed to create the inner container, it takes courage to create the outer container. Without a sense of aliveness in the environment, the participants will be less likely to sense their connection to one another. Deliberately enlivening the environment with beauty and an optimal seating arrangement will go far in bringing needed group cohesion.

PRINCIPLE

Clear and accepted boundaries integrated with an enlivened environment allow safety and openness.

If we expect the participants of any gathering to be authentically engaged, open, honest, and perhaps vulnerable, as well as to feel connected to one another, the Convener’s role is to be vitally aware of and attentive to the energetic boundaries and physical conditions of the gathering—simultaneously.

When we speak of “holding the people,” a large part of what we are referring to is this attentiveness to the inner and outer containers. Our attention to these boundaries and conditions is a precious gift to the participants of our gathering, creating the potential for their wholehearted openness.

ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS

What is needed for the participants to feel safe in this gathering?

What will enliven the environment?

What protocols and agreements must be present?

We ask ourselves these questions so that we will be prepared to create the container for our engagement when the time comes. We return to the questions over and over as we design the space for our gathering and as we think about what the agreements and protocols will be.

Our surroundings play a vital role, so we consider carefully where we will meet. Whatever space we choose, we ask ourselves how we will enliven the environment for optimal connection.

We might find that each gathering we convene requires the same or similar terms of engagement, or we may find that the participants of certain engagements require very specific or customized agreements and protocols in order to feel safe. Part of our work here will be to keep our attention on what is needed for the particular group that is gathering.

MAKING IT REAL

The outer and inner containers for our gathering require thoughtful consideration.

OUTER CONTAINER

The physical container is the location or place in which we meet. When the environment is alive and has beauty, the space itself feels inviting and welcoming. An office space or conference room with windows; a charming restaurant; a sidewalk café; or a public space with exposure to a pretty view, art, living plants, and beauty can be perfect for some types of gatherings. Sometimes, though, we don’t have the luxury of choosing where we will meet or gather. As Conveners, we still ask ourselves how best to enliven the environment we will be in to honor the participants as living human beings.

In places prepared with thoughtfulness, we are more likely to feel a stronger human connection. To bring this aliveness to the environment, we prepare the room or space so that there is something of nature, art, and/or beauty present. A vase of flowers in the center of the room, art, an engaging view of the outdoors, and an arrangement of natural objects are all things we use to our advantage to create a living environment.

OUR MEETING PLACES MATTER. Often we are faced with meeting spaces that are angular, sharp-edged, and devoid of natural lighting, windows, and art. Sometimes little to no attention has been given to bringing the full human experience to our workplaces or other social institutions. It often seems odd to hear music or experience beauty outside of the occasional celebration in our offices.

We spend much, if not most, of our work lives indoors, engaged in our individual passions and labors either alone or with others. Do we give the same care and attention to our work and meeting spaces as we may to our homes and other living situations? Do we treat them with the same care and friendship as we do our favorite places? Do our meeting spaces bring us to life or bring us down?

The spaces designated for us to meet are often no more than a nondescript cube in which we’re expected to carry out the most inspired work of the day. The room may include chairs and tables; media to service our communication needs; bright lights; spare walls; and—at best—a few windows, subdued art, and perhaps a potted plant. This is what we have come to expect of our meeting spaces.

A primary rationale for our lack of attention to our outer container is the concern about losing control over our surroundings. It goes something like this: if we bring too much of our personal selves (human qualities)—beauty, heart, compassion, creativity, and so on—into our meetings, we’ll lose our clearheaded objectivity and focus that drive results. The distrust is that, unless we control the environment with little to no outside stimuli, people will goof off and ultimately be unproductive.

If we don’t create venues and spaces that allow for authentic engagement to emerge, then we’ll pay for it in the long run when committed action is called for from the people. Trust and respect are directly proportionate to the level of belonging and interdependence that people feel in their relationship to one another. Without an experience of authentic connectivity, lasting commitment and accountability to one another and the task at hand is not likely.

We often create a circular seating arrangement when we convene at Heartland because it induces a collegial feel, and everyone can see and be seen by everyone else. This configuration also facilitates authentic engagement among the participants. It takes some courage to set the room in a way that may be unexpected or considered frivolous, but we continue to create the environment that seems the most conducive to our objective of bringing authentic engagement to the group.

Surroundings that allow us to feel secure and give us a sense of belonging tend to make us less apprehensive and stressful. When we feel safe and taken care of in our outer world, our inner world follows suit. We have a better chance of approaching our engagement as whole and healthy people to the degree that we experience security and connectivity to our surroundings and our colleagues, family, or friends.

PRACTICAL MATTERS IN CREATING THE OUTER CONTAINER. The possible configurations in which we design our meetings and gatherings are limitless. Let’s begin by considering our intent, the content, and outcomes. Think of your meeting space as a blank canvas, and that you are building on its assets rather than liabilities.

Consider how to maximize presence, connectivity, understanding, and action. These are the foundational objectives for any engagement.

Presence. We’ve laid the groundwork for everyone to be present through setting context and accepted agreements for our engagement. Now, how do we play on the physical design of the meeting space to maximize the full presence of everyone throughout the session?

Connectivity. What design forms allow for high levels of essential interaction among the participants— interaction that stimulates learning, retention, creativity, and ultimately a commitment to action?

Understanding. Access to knowledge and information is not a requirement for absorption and understanding. When we provide environments where presence and connectivity are valued, the potential for the assimilation of information and knowledge into useful understanding is greatly enhanced. Understanding is the gateway to wisdom.

Action. Has our space been designed to take advantage of the opportunities to bring our creativity to full flower through action?

Action may be defined in many ways, from meaningful conversation to specific outcomes. In The Answer to How Is Yes: Acting on What Matters, Peter Block tells us that conversation may be the ultimate action step.2

Start slowly and build. We are creatures of our own traditions and rituals. Make small design changes and build from there.

In the box below is a discussion of some often-overlooked issues to consider when designing the physical space of a meeting or gathering. Think about these suggestions and tips as generalized principles you may apply to your own setting with the objective of having an enlivened environment, and proceed from that perspective.

Take an inventory of the architecture, design, and amenities of the space in which you are working. What do you have to work with? Look at everything as a tool in your tool kit. Use cultural icons whenever possible, familiar images, perhaps company logos or other symbols.

Windows/lighting. The ability to see the world outside of the meeting room often changes the mood of the participants. For instance, at a recent meeting where people could see natural beauty outside, many commented that the beautiful view was calming and satisfying, leading to a greater capacity to participate.

If your space does not have natural lighting, can you bring in floor lighting to soften the glare of overhead lights?

Walls. As an interior designer, what do you have to work with? Artwork? Textiles or tapestry? Even flip-chart paper or quotes on squares can break up broad expanses to create more interesting spaces in which to spend time.

Doors. Where are they in relation to the meeting space? Doors offer opportunity and surprise. Be aware of and seek to control where and how people enter and exit the meeting, if possible. A good configuration will enable late-arriving participants to be less disruptive and lessens the chance that passersby will be inadvertently distracting.

Media. Many of our gatherings employ all sorts of media, from screened presentations to audio surround and personal devices of every shape and size. The rule here is to know when they are useful or not, and then have clear, agreed-upon protocols for when and how they are used. In this age of cell phones, iPods, BlackBerrys, and other ubiquitous personal devices, clearly indicate what is expected to be off, silent, or on. Otherwise, the room could become a hijacked media ping-pong match.

Tables and chairs. When possible, rearrange and configure furniture to your purpose.

• Know that whoever is standing is in charge and has the stage.

• Know that tables are great for storing and holding stuff, but not necessarily beneficial for engendering meaningful discourse.

• Know that rows of chairs, theater style, allow people to hide and make it harder to keep their attention.

• Know that most chairs are uncomfortable, and 40 minutes in one sitting is about all that people can take.

• Know that you have the right and permission to shift the energy by playing musical chairs when the time is right, perhaps after a break.

Make sure that your seating arrangement takes these things into consideration. We think that having everyone seated in an open circle is the best configuration for most of our gatherings, but other configurations may be optimal for certain types of gatherings (see below).

CIRCLES, SQUARES, AND ROWS

How we meet defines the conversation. Although there are varied contexts for our meetings, the circle, square, and row seem to be the forms in which we meet the most. So let’s look at what is best for what type of gathering.

Squares. Our most familiar form of gathering for meetings is in geometric configurations around tables. We also tend to meet around tables in more informal settings, such as at coffeehouses and restaurants. The table-and-chairs format is well suited for cognitive and intellectual exchanges of data and information. We are able to cohabitate with media, food, and other meeting props as we engage. These formats tend to be more formal, sacrificing the full body intimacy of the circle for the purpose of more utilitarian exchanges. Utility and the transaction of ideas, information, and concepts are its strengths.

Rows. Theater-style meetings are best used for clear and direct presentations, whatever their content. The row configuration is best used for absorption and learning in an efficient use of space where all consumers are able to experience the same material at the same time, and there is no wish for them to participate any further (except possibly in limited ways, such as a question-and-answer segment).

The circle. The most ancient “technology” for human gatherings most likely started around the campfire and continues today as the most effective form of creating presence and connectivity. The circle creates equality and peerage among those present, even in a hierarchical environment. As a practical matter, we use a single-circle seating configuration for our gatherings typically of groups of under 75 people, without microphones. We have found that concentric circles for larger-scale assemblages are effective in achieving intimacy as well. The practical advantages of circle seating are as follows:

• Everyone can see and hear one another. Imagine meetings where all can see and hear one another. There is no hiding out in the circle. Without tables, there is a presence and a demand for attention to one another that no other meeting form affords.

• It induces a nonhierarchical structure in which sharing at a more engaged level is accepted and invited.

• Circles provide recognition (seeing) of the whole community and are adaptable to smaller breakout groupings for more intimate conversations.

• Circles have been used successfully in community and faith-based venues, and more recently have been introduced into business settings because they allow participants to get to the heart of the matter more quickly than do other meeting forms.

Note the United Nations and various round-table discussion groups as examples of collegial environments using the circle.

Changing the physical space takes courage. People will react. Take a deep breath, knowing that you are bringing your gift to the group.

As one of the senior organizational development (OD) planners for the upcoming Best in the West Conference, an event held every year by the San Francisco Bay Area OD Network Conference attendees, I had an inspiration! Rather than bemoaning the uninspiring and flat opening of previous conferences, we decided to use the structure and design elements of the Art of Convening.

I seized the opportunity to design an opening that reflected the spirit of our OD practices and create real community among us. I spoke with the keynoter, the conference chairs, and the board chair to clarify the intent and ensure that we were all aligned. I enlisted two to three close colleagues to assist and support the process.

On the day of the event, as emcee, after setting the context for the conference, I invited participants to join me in the circle—and a big circle it was, in a cavernous auditorium with three circles of chairs to accommodate 170 people. There was a beautiful centerpiece of purple and white irises on a purple and white cloth. What a contrast to the year before! I asked permission to convene this inspiring and exciting group vibrating with energy. I then invited everyone to take a deep breath and, in a moment of silence, to become present from their travels to the conference, and to reflect on their intent for the day … learning new skills, networking and meeting new colleagues, presenting or learning new ideas. I reviewed the agenda for the opening session, which included hearing our speaker, taking a short break in the middle of the presentation to share the implications with a partner, and a closing reflection. After I reviewed the rationale and the ancient history of the circle, the value of seeing each other and hearing all our voices, and how we were creating community, I described the concept and purpose of “stringing the beads,” and we began to hear all the voices of those present in the room.

These were not new structure or design elements for OD practitioners, but it was new to bring these elements to the opening session of the conference in such a large group. Because of predetermined schedules, there was not as much time as I would have liked to create this opening community event. But despite the time constraints, it worked! Many attendees talked about the welcome sense of openness, the spirit of sharing, and the feeling of community that carried through the day. Perhaps next year will bring a more flexible schedule.

—By Bev Scott3

THE INNER CONTAINER

The energetic field or inner container for our gathering refers to the energy or chemistry created and sensed within the people attending. This field is created with the terms of engagement, or the agreements and protocols we hold for our gathering. Protocols and agreements serve as the social norms of our container, allowing people to feel safe enough to share their gifts at a meaningful level. Feeling safe is imperative if we are to bring authentic engagement to the group.

We have a love/hate relationship with structure. When the social form and function is clearly stated and agreed upon, an energy is released that allows the container to be formed. In the absence of clear and requested agreements, there is no freedom within the assembled. Knowing the terms of engagement enables the participants to make an informed choice to accept or not. There are ways to elegantly navigate this element.

ASKING FOR AGREEMENT. We’ve identified reluctance to impose our will as the main challenge in Creating the Container. Being perceived as authoritarian or rigid can be uncomfortable for many of us. However, establishing boundaries requires us to be neither authoritarian nor rigid. We simply ask the others for agreement. Part of this asking, and a way to convey that we are the Convener, is to ask the group for permission to be the Convener.

Since we are the ones calling the meeting and inviting people to attend, we may think it is assumed (see chapter 4) that we are the Convener, but it is important to the common understanding of the gathering going forward that we restate our role as Convener and ask for permission (get buy-in) to assume this role. The participants are likely to experience security in knowing who’s in the leadership role.

Once there is a common understanding that we are the Convener, we briefly describe what the Convener will do. For example, the Convener will mark time, will lead transitions, and will open and close the gathering.

Once we are established as the Convener, we state the protocols and terms of engagement for the gathering. There is some flexibility here, but important protocols that are almost always present in our gatherings are confidentiality (what is said here stays here), how we are to acknowledge and respect who has the floor, and when people are expected to listen or to speak.

For large groups or for groups on the phone, an efficient and effective practice is to tell people that their silence signifies agreement. Of course, the participants must then have the ability and freedom to speak up if they don’t agree. Another (more time-consuming and messy but perhaps necessary for some groups) way to obtain agreement is to poll each person one by one, asking for “yea or nay” or a show of hands.

UNLOCKING THE CONTAINER

As the women arrived, I could sense an energetic jumble of feelings, including both anticipation and hesitation. My first task, as coach and facilitator, is to create a safe container for our time together.

The stated purpose of our session is to “unlock our passion, potential, and purpose for joyful living.” To create the spaciousness for this to occur requires certain structures and protocols that allow for the wisdom and willingness of the group to emerge.

After a brief meet and greet, I rang a small bell and invited the 10 women into the circle. This welcoming space had been prepared with comfortable chairs gathered around a beautifully carved low table, where I had placed both candles and flowers along with several strands of colorful beads. This would serve as the focal point of our physical container for our time together.

Creating an energetic container conducive to engaging in rich and meaningful conversations was next. I began by enumerating certain agreements and protocols that would provide safety and structure for our gathering. The women were asked to detach from phones and other distractions, to leave their to-do lists behind, and to commit to being fully present. We spoke about the circle and its deeper symbolic meaning, and then discussed the need for absolute confidentiality. When I assured them that no one would be asked to share anything beyond her personal comfort level, I could feel a collective sigh of relief. Finally, I explained the format for respectful listening, sharing, and conversation that we would adhere to, and that it would be my responsibility to “hold the space” and to move things along.

—By Minx Boren5

CREATING THE VIRTUAL CONTAINER

Our attention so far in this book has been focused mainly on “in person” engagements. Our multimedia world offers us a much broader range of opportunities to convene in the virtual world, from conference call meetings and webinars to social media network gatherings and other electronically based community environments.

Since 2004, Heartland has pioneered convening in virtual space through our Art of Convening TeleTrainings using telephone and Internet technologies as the gathering and learning platform for teaching the principles and practices of convening.

After six years of practical application with hundreds of classes and thousands of contact hours, we’ve found that the core principles of the Convening Wheel apply to virtual as well as in-person gatherings. There is no discernable difference between the fundamental ways in which we convene by conference call or in an onsite meeting.

In the story to follow, we’ll see how the “virtual container” is a very effective way of Creating the Container for a gathering on the phone or in another medium where we are not physically together.

Don’t underestimate the power of the human imagination to create the perfect setting in which to meet. With help from the Convener, the participants are able to imagine themselves together in a setting that, while customized to each individual, provides a common area to gather and “see” one another. The following story illustrates how we create a virtual “place” in the campfire around which we meet. Using our imaginations, we’re able to place ourselves together in an environment that we can hold as real for the duration of our time together.

As you’ll see in the following story, agreements and protocols become essential in the creation of the virtual container.

THE VIRTUAL CAMPFIRE

The Art of Convening TeleTraining group had arrived. Each of 10 participants, from various parts of the country, had dialed in to a two-hour teleconference session by phone. Each was greeted by name with a heartfelt “Welcome” and engaged in lighthearted conversation as the time to start approached. At the scheduled time, Craig, the Convener, said, “Let’s begin.”

Craig announced the context for the session, with its themes and agenda, and introduced the co-Convener. He then stated the protocols to be observed on the call, requesting that each participant agree or not to the following:

“We agree to be fully present. To call from a quiet place alone and free of distractions, excusing ourselves from all other engagements; we disconnect from e-mail, computers, and electronic media.

“We agree to confidentiality. What is said on this call stays within this group. Please don’t share with people outside of this group.

“We agree to identify ourselves. We will say ‘I am’ and our name when we begin to speak, and ‘I am complete’ or some other closing signal when we are finished speaking so that others may know we are not just pausing.

“We agree to ask for what we need and look for surprises.” Craig continued, “I ask your permission to be the Convener. I’ll be marking time and leading the session.”

“If you don’t agree or have questions about these protocols, please speak up; otherwise, I take your silence to signify your acceptance.” He paused for a few seconds in silence. No one spoke.

Acknowledging that they were each in separate spaces and had only the virtual space connecting them, Craig asked the participants to imagine themselves sitting around a campfire. He began, “Imagine the weather is pleasant, the fire is warm and inviting, and we are all seated comfortably, able to see one another around the fire …” He continued to set the scene for an intimate group sitting around a campfire, together.

Thus the virtual container was created. As the session proceeded, the participants were held, virtually, in an atmosphere of natural life, beauty, and safety.6

AGREEMENTS AND PROTOCOLS CHECKLIST

1. Start on time and end on time. People trust people who are punctual and clear about their time boundaries. Punctuality is a sign of respect and shows that we take each other seriously.

2. Know who is convening, and ask for permission from the assembled for that person to convene, especially if it is a shared or co-led event.

3. An efficient way to ask for permission of any sort from the group is to state, “Your silence signifies agreement. If you have questions or don’t agree, please speak up; otherwise, agreement is assumed.”

4. Be sensitive to when confidentiality is appropriate, and ask for agreement from everyone when this is the case. Simply say, “Whatever is said here stays within this group. Share your experience but not that of anyone else by name.”

5. Humor and not taking ourselves too seriously is always a good idea.

6. Make clear the cultural norms you will be observing, or not. Examples: Prayer at the beginning of a faith group. Acknowledging hierarchical norms during meetings (for example, “In this meeting, we will use first names.”).

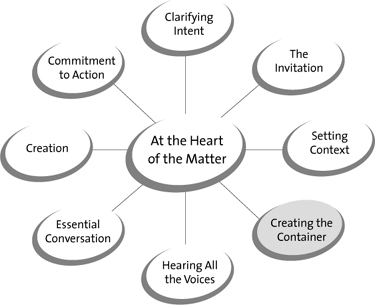

WHERE WE ARE ON THE CONVENING WHEEL

1. At the Heart of the Matter—We have explored who we are and how we will be in relationship with others.

2. Clarifying Intent—We have identified an intention consistent with At the Heart of the Matter that has substance and is acted upon.

3. The Invitation—We have extended a sincere invitation with genuine hospitality, generosity, and conviction.

4. Setting Context—We have clearly communicated the form, function, and purpose of our gathering.

5. Creating the Container—We have prepared a physical space with beauty and life, and we have agreed on terms of engagement or protocols that bring safety for our time together.

Creating the Container provides us with a safe and conducive space for our engagement to unfold. As the participants settle into this container, we call each to be “present and accounted for” by Hearing All the Voices—the next Aspect of the Convening Wheel.

Things to Remember

Challenge: Reluctance to impose our will on others. Are we willing to step forward to establish the boundaries of the gathering?

Principle: Clear and accepted boundaries integrated with an enlivened environment allows for safety and openness.

Essential Questions:

• What is needed for the participants to feel safe in this gathering?

• What will enliven the environment?

• What protocols and agreements must be present?

Aspect-Strengthening Exercises

Checklist for the Gathering at Hand

• Does the gathering environment feel alive? If not, what can I do to introduce life and beauty?

• Do I know what the terms of engagement will be, and am I prepared to ask for all to agree?

EXERCISE 1: REFLECTING ON BEAUTY

Recall the last time you experienced an expression of beauty in your meetings. What were the psychic, emotional, and physical impacts on the people, and the outcomes?

• Pick out one or two elements that were meaningful to you, to begin to create a standard for future engagements.

• Experiment with them to create a baseline form for your engagements.

EXERCISE 2: PICTURING

Picturing an upcoming meeting, create a list of new ways to bring beauty and aliveness, and to activate the space.

• Experiment with ways to bring a room or environment alive with nature (flowers/plants), art, light, sound, temperature, scent, and/or view.

• Is there a fresh way of envisioning the room and its contents, and how participants will interact with one another?

• When you walk into a room, notice and familiarize yourself with the room—windows, doors, other objects, and furniture. Touch each place where a person might sit, and imagine what it would be like to sit there.

Journaling Questions

• In designing physical spaces for human interaction, what considerations would you make for bringing aliveness to the engagement? List some specific examples.

• In designing an engagement to hold a safe field for the people involved, what agreement and protocols would you use? List specific examples.