SECTION 4.0

An Evaluation of the Impact of Emotional Intelligence Training

4.1 Introduction

With increasing evidence suggesting that emotional intelligence (EI) is able to predict a wide range of key behaviors associated with effectively working in and managing projects (Butler & Chinowski, 2006; Leban & Zulauf, 2004; Muller & Turner, 2007), the question of whether emotional intelligence can be developed is becoming of far greater interest to the project management community. The expectation is that, by developing the emotional intelligence of those working in projects, gains should eventually be seen in terms of improvements in those project management behaviors deemed important to successful projects (Turner & Lloyd-Walker, 2008). Determining whether emotional intelligence can be improved through training and development interventions for project managers is therefore an important first step. However, building a significant body of knowledge to underpin training interventions in this area presents a number of significant challenges. In a recent review of emotional intelligence training, Clarke (2006b) concluded that there was minimal evidence available to support many of the claims that EI training was effective. Furthermore, the use of differing EI models to underpin training, alongside the disparate measures used to evaluate its impact, meant that the literature was both fragmented and lacking in coherence. Making comparisons across studies to identify factors associated with the design of training that might be associated with its effectiveness is therefore also difficult.

From a developmental perspective, how emotional intelligence is characterized, either as a set of dispositions or personality attributes (Bar-On, 1997; Dulewicz & Higgs, 2003), cognitive abilities associated with the processing of emotional information (Mayer & Salovey, 1997), or a taxonomy of competences (Boyzatis, Goleman, & Rhee, 2000), clearly has considerable implications for designing the content and delivery of any developmental intervention. The use of these differing models to underpin training interventions also raises far more complex questions as to whether emotional intelligence as defined by these differing perspectives can actually be developed at all. For example, those dimensions of emotional intelligence models that seem to share greater resemblance to aspects of personality may be far less amenable to change through training, given that personality is widely recognized as a set of relatively stable patterns of characteristics and dispositions (Donnelian, Conger, & Burzette, 2007; Gross, 1987; Rantanen, Metsapelto, Feldt, Pulkkinen, & Kokko, 2007). In addition, despite accumulating research which suggests that the ability model of EI may have greater construct validity, relatively few studies have been published that have specifically investigated the impact of training interventions using this model.

It is within this context that this study makes a contribution to the literature by presenting findings from an evaluation of an emotional intelligence training program that was designed to target a number of participants’ emotional intelligence abilities. The results show some positive effects for training. Beyond identifying training impact, the study also advances theory building in this area by identifying factors associated with the design of training that appear associated with the development of EI ability. Finally, the study makes a contribution more specifically to the project management field, by examining the effects of training on a sample of project managers in the UK, and identifying whether changes also occur in their self-assessed project management competences. The findings are therefore of particular significance for those considering how best to design development strategies to enhance project management performance with emotional intelligence as a key focus.

4.2 Findings From Emotional Intelligence Development Studies to Date

A search of the literature located seven studies that reported evaluations of interventions designed to develop emotional intelligence (Table 8). Two of these studies used competence based measures of emotional intelligence drawn from Goleman's Emotional Competence Inventory (Sala, 2006; Turner & Lloyd-Walker, 2008). Sala (2006) reported the results of two training programs, one involving 20 managers and consultants and the other involving 19 participants from a U.S. accounting organization, collecting postcourse measures at 8 and 14 months, respectively, for the two groups. Positive effects were reported for the training on 8 of the 20 emotional intelligence competence areas examined. Turner and Lloyd-Walker (2008) evaluated the impact of a training program on 42 project management employees based in a U.S. defense project. Emotional intelligence was assessed through self- and peer ratings using Goleman's (1998) Emotional Competence Inventory (Boyatzis, Goleman, & Rhee, 2000). Measures of job satisfaction and job performance were also collected with all postcourse measures collected 6 months following training. Generally they concluded positive effects for the training intervention in terms of self-ECI ratings but no effects for peer ratings of ECI competences. The picture was somewhat more complex, in that most of the positive effects for self-evaluations were at the 0.10% level of significance and a number of the peer-rated competences, when looked at individually, actually decreased (three at the 0.05% level and one at the 0.10% level of significance) following training. Statistically, significant changes were found in job satisfaction and job performance, although only at the 10% level of significance.

One study evaluated EI development interventions using both trait and mixed model emotional intelligence measures. Slaski and Cartwright (2003) presented the results of a study to investigate the impact of EI training, and whether increased EI also had a positive effect on health and well-being. Based on a sample of 60 retail managers, they evaluated the impact of five training programs delivered 1 day per week for 4 weeks, with 12 managers attending each program. A pre/posttest research design with a comparison group was used where training participants completed two measures of emotional intelligence, the EQ-i (Bar-On, 1997) and the EIQ (Dulewicz & Higgs, 2003) as well as three measures of health and well-being, and pre-training, which was repeated 6 months later. Fifty-two and forty-nine complete data sets were obtained from trainees and managers in a control group, respectively. A positive impact for the training was reported with statistically significant improvements found in the EI measures used (the overall EQ-i score and a number of its subscales, and similarly in the overall EIQ score and all except two of its subscales). Positive changes were also found in measures of health and well-being.

The remaining four studies all evaluated EI development interventions based upon Mayer and Salovey's (1997) ability model of emotional intelligence. Two of these, however, used self- and peer-assessed measures of emotional abilities. Based on a sample of 82 undergraduate students participating in self-directed teams as part of a 12-week organizational behavior course, Moriarty and Buckley (2003) reported positive findings for the impact of the intervention on EI. Using a pre/post-test research design and a team-based measure of emotional intelligence (the WEIP-5, Jordan & Troth, 2004), significant positive changes were found in one of the two self-assessed EI measures of EI abilities. Findings from the peer-assessed measures of EI showed statistically significant improvements in both EI ability dimensions. By contrast, scores obtained from a sample of 80 students participating in a control group showed no change. Similarly, Groves, McEnrue, and Shen (2008) reported the results of an 11-week undergraduate management course that incorporated a specific focus on emotional intelligence, based on a sample of 75 students in the experimental group and 60 students in a comparison group. Again using a self-report measure of EI abilities developed specifically by the authors (the emotional intelligence self description inventory (EISDI)), statistically significant improvements in all four EI ability scores and overall EI score were obtained. No statistically significant changes were found in the control group.

Instead of using self- and peer-reporting measures, both Meyer, Fletcher, & Parker (2004) and Clarke (2007b) used an ability-based test to assess emotional intelligence (the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso-Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT)), which is widely recognized as perhaps the most robust and valid measure of emotional intelligence currently available (Roberts, Zeidner & Matthews, 2001). Both studies reported mixed results with positive effects found only in a few of the emotional abilities examined. Meyer et al. (2004) evaluated the affects of a 1-day adventure (outward bound) training program on a sample of 15 dentists and administrators and found that positive effects on emotional abilities varied according to the subgroup of trainees. Clarke (2007b) undertook a larger study involving 64 MBA students participating in a 14-week self-directed team project and 13 students participating in a comparison group. Positive effects were only found for the ability of using emotions to facilitate thinking, but this was only for those students who had participated in team learning more intensively (that is, attended team meetings once per week or more). No statistically significant changes were found in the comparison group.

Based upon these studies, it would seem that developmental interventions can have an impact on emotional intelligence, but that the criterion measure used to assess emotional intelligence would appear to make a difference. Far more positive results are found for those studies using self- and peer-assessed measures of emotional intelligence irrespective of the EI model used (Groves, McEnrue, & Shen, 2008; Moriarty & Buckley, 2003; Sala, 2006; Slaski & Catrwright, 2003; Turner & Lloyd-Walker, 2008) but these suffer with validity problems due to the social desirability effects of self-reporting. Only two studies from those mentioned previously have used what might be considered more objective ability tests of emotional intelligence, and the findings here are far more cautious regarding the potential impact of development interventions (Clarke, 2007b; Meyer, Fletcher, & Parker, 2004). Despite suggestions in the literature, then, that training may have a positive effect on emotional intelligence (Bagshaw, 2000; Cherniss & Caplan, 2001; Clark, Callister, & Wallace, 2003; Dulewicz & Higgs, 2004; Watkin, 2000), there is in effect a paucity of data available to reach any confident conclusions. It is also difficult to determine from these studies in what ways the duration of any development intervention plays a role in their effectiveness. From those studies previously reported, positive effects were found as a result of both relatively short durations occurring fairly intensively over 1 to 2 days (Meyer, Fletcher, & Parker, 2004; Sala, 2006; Turner & Lloyd-Walker, 2008), as well as those occurring over a longer time frame such as over 5 (Slaski & Catrwright, 2003), 10 (Groves, McEnrue & Shen, 2008), 11 (Moriarty & Buckley, 2003) and even 14 weeks (Clarke, 2007b). Given the significant cost and resource implications associated with longer-term development interventions, identifying what effects, if any, targeted, short-term programs might have on emotional intelligence, is clearly of importance.

There is also a further theoretical issue to consider. Given that a significant amount of research to date is showing positive relationships between more objectively measured emotional intelligence abilities and behaviors associated with teamwork and leadership, major questions concerning the use of appropriate criterion measures for evaluating training effects must be addressed. It would seem to follow that in order to maintain theoretical and empirical consistency, far more studies are needed that focus on identifying whether and how emotional intelligence abilities develop and if so, under what conditions. It should not be expected that training results showing improvements in one type of EI measure will necessarily translate into the benefits expected as a result of research based upon completely different EI measures. Given that only two EI development studies have to date been conducted using objective ability test measures of EI, further studies using this measure are clearly needed.

From a project management perspective, there is also a need for studies that examine EI development interventions and whether these can be tracked to improvements in the attitudes and behaviors necessary for project management. Despite significant interest in the concept of emotional intelligence within project management (Drukat & Druskat, 2006), this is still a relatively unexplored concept within the field. Although some progress has been made in examining relationships between emotional intelligence and project management behaviors associated with leadership (Muller & Turner, 2007), research examining interventions for developing emotional intelligence in project managers is very much embryonic. The findings from the one evaluation study so far conducted by Turner and Lloyd-Walker (2008), although using a competence-based measure of emotional intelligence, also suggest that designing training interventions that are targeted specifically for project management may be an important factor to consider in maximizing the effectiveness of any training. They based their training on standard, generic training content rather than on specifically contextualized training for project management and found some positive effects in relation to some self-report measures. However, they also obtained negative effects or no changes with respect to peer report measures of EI.

For some time, it has been recognized in the training literature that learning is more likely to be supported more closely when the training content is able to mirror the actual work environment or job role (Baldwin & Ford, 1988). EI training that is far more contextualized and seeks to examine the use of emotional intelligence abilities within relevant and particular job contexts, may therefore be more effective. Turner and Lloyd-Walker (2008) also found no effects for the impact of EI training on job performance measures, although improvements were found on project managers’ job satisfaction 6 months later. Far more research examining links between EI training and its effects on particular project management attitudes and behaviors is therefore needed.

4.3 Focus of the Current Study

The second component of the pilot study therefore aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of an emotional intelligence training program designed specifically for project managers. The focus of the study was to address the following objectives:

(1)To determine whether training can result in improvements in project managers’ emotional intelligence abilities and relevant project management competences.

(2)To identify factors that may be associated with the effectiveness of emotional intelligence training.

Three specific hypotheses tested in the study and their rationale were as follows:

In relation to the development of emotional intelligence abilities, positive effects have been previously found for short-term training interventions targeting emotional accuracy recognition (Elfenbein, 2006) as well as with some branches of emotional intelligence abilities contained in the four-ability model (Meyer, Fletcher & Parker 2004). By contrast, findings from both quantitative and qualitative studies investigating the development of emotional abilities through workplace learning approaches have suggested that development is more likely to occur over a far longer time period involving a number of months or more (Clarke, 2006a, 2007b; Groves, McEnrue, & Shen, 2008; Moriarty & Buckley, 2003). Clarke (2007b) previously suggested that emotional intelligence training may provide trainees with an initial awareness of their emotional abilities, but that this is only a platform from which further development may occur as a result of learning which occurs on the job (workplace learning). This occurs as a result of trainees bringing their EI abilities to a more conscious awareness in their approaches to dealing with emotional experiences in the workplace, a process Clarke (2006a) refers to as “emotional knowledge work.” Given that projects are increasingly recognized as emotional places (Chen, 2006; Peslak, 2005), participation in projects should subsequently offer significant opportunities for EI development. Based on this reasoning, training should not be expected to have any immediate effects on emotional intelligence abilities, but only after a period of some months has elapsed and participants have engaged in further workplace learning opportunities arising from participating in project work. This gives rise to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6: Positive changes in the emotional intelligence abilities (1) perceiving emotions, (2) using emotions to facilitate thinking, and (3) understanding emotions, will not be found immediately after participants have attended training but will be found 6 months later.

Although suggested as lying outside the ability construct of emotional intelligence, the dispositional tendency of empathy has been proposed as a characteristic of emotionally intelligent behavior (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Previous studies have found moderate correlations between ability emotional intelligence and self-judgments of empathetic feeling (Brackett et al., 2006; Caruso, Mayer, & Salovey, 2002) suggesting it is a related but independent construct. Empathy involves a capacity for recognizing feelings in others, which requires a level of emotional awareness. Empathy, therefore, depends on the ability to perceive emotions (Mayer, Roberts, & Barsade, 2008). We should therefore expect to see increases in participant measures of empathy as a result of increases in their emotional intelligence abilities. This gives rise to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 7: Significant increases in participants’ empathetic ability will be detected 6 months following participants’ training, but not immediately after training.

A number of authors have suggested that emotional intelligence may be an important aspect of individual difference that is associated with the skills and competences necessary for working in and leading projects (Druskat & Druskat, 2006; Muller & Turner, 2007; Leban & Zulauf, 2004). Turner and Lloyd-Walker (2008) have previously suggested that training in emotional intelligence should influence project managers’ performance, and Mount (2006) found that emotional intelligence competences accounted for 69% of the variation in the skill set which project managers considered to be key for successful projects. The findings from study one presented earlier showed that emotional intelligence abilities were associated with the two project management competence areas of teamwork and conflict management. Significant changes in these two specific project management competences should therefore be expected as a result of improvements in participants’ emotional intelligence abilities through training. This gives rise to the final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 8: Training will result in positive improvements in project management behaviors (competences) associated with teamwork and conflict management 6 months following training, but not immediately after training.

4.3.1 The Training Intervention

This comprised a 2-day training program that was designed to improve a number of targeted emotional abilities and empathy among the participants specifically within a project management context. The training program was delivered on three separate occasions to three groups of project managers. Two groups of project managers were drawn from two organizations that were approached to participate in the study. The third group comprised participants from the UK chapter of the Project Management Institute who responded to an advertisement to take part in the research project. The total population of trainees combined both those attending voluntarily and those requested to attend by their organizations. It was expected that positive change in EI abilities should occur after 6 months and that this should also result in improvements in the three project management competence areas assessed. A comprehensive explanation of the theoretical underpinnings informing the development of the training, the nature of the content, and details of the material covered are provided in section six.

4.4 The Study and Methods

The study employed a pre/post-test quasi-experimental design (Campbell & Stanley, 1963) with measures of emotional intelligence collected 1 month prior to participants attending the 2-day EI training program (Time 1), again 1 month following the training (Time 2), and then again 6 months post training (Time 3). There were 57 project managers enrolled to take part in the training study. In addition, 18 project managers volunteered to act as a comparison group by completing measures but not attending training. Major problems with participant attrition resulted in only 36 complete data sets being obtained (containing measures from all three time points). A larger number (53) of the matched baseline and second postcourse (6 months later) were obtained, however. In order to maximize the statistical power of the tests, it was decided to run two sets of independent tests. The first set examined differences between all baseline measures and those obtained six months later using the larger data set (n=53). The second examined differences between the baseline and the first set of postcourse measures collected 1 month following training from the smaller subset (n=36). The characteristics of the larger sample of 53 training participants were as follows: the majority, 32 of these participants, were female (60%) and 15 (28%) were certified project managers; and the average age was 39.7 (SD 8.3) and ages ranged between 23 and 58. These participants indicated their job roles as follows: general management 14 (26%), marketing/sales 2 (4%), HRM/training 1 (2%), finance 2 (4%), R&D 2 (4%), technical 4 (8%), and other 28 (52%). Significant attrition was also encountered with the comparison group with matched baseline and 6 month postcourse measures obtained from only 6 of the 18 project managers volunteering to take part. As a result, it was decided to exclude data from the comparison group from subsequent analyses.

4.4.1 Dependent Measures

The following competences were assessed:

1) Emotional intelligence. The Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT V2.0) (Mayer & Salovey, 1997) was used to assess the three emotional intelligence abilities: perceiving emotions, using emotions to facilitate thinking, and understanding emotions. Each of the three abilities is comprised of two task areas. The first exercise, the face-and-pictures tasks, required respondents to indicate the extent to which emotions were indicated by the visual stimuli, rated on a five-point Likert scale. Two tasks that assess the ability of using emotions to facilitate thinking ask respondents to consider the utility of certain emotions for facilitating behaviors (facilitation task) and judge comparisons between emotions being felt by an individual in a scenario to colors and temperature (sensations task). Two additional tasks, labeled as changes and blends tasks, require respondents to identify possible reactions given an individual's emotional state and to indicate how more basic emotions might combine to form more complex ones. Previously, reliabilities for each of the scales have been reported as 0.90, 0.76, and 0.77 (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2002). Reliabilities obtained for each of the three branches on the first administration were 0.88, 0.62, and 0.95, respectively. At the second administration, coefficient scores were 0.89, 0.57, and 0.90, respectively.

2) Empathy. Mehrabian and Epstein's (1972) 33-item of emotional empathy was used to assess empathetic tendency. Responses to each item are on a scale ranging from +4 (very strong agreement) to –4 (very strong disagreement). Scores on 17 items are negatively scored, in that the signs of a participant's response on negative items are changed. A total empathy score is then obtained by adding all 33 items. Sample items include: (1) (+) “It makes me sad to see a lonely stranger in a group”; and (24) (–) “I am able to make decisions without being influenced by people's feelings.” The scale authors previously reported the split-half reliability for the measure as 0.84. Here the Spearman-Brown split-half coefficient was found to be 0.86, suggesting good reliability.

3) Project Management Competences. The teamwork competence was assessed using a 7-item scale. Sample items included: (1) Built trust and confidence with both stakeholders and others involved on the project?; and (2) Helped to create an environment of openness and consideration on the project? Conflict management was assessed using a six-item scale. Sample items included: (1) Recognized conflict; and (2) Worked effectively with the organizational politics associated with the project. Reliability coefficients were found to be satisfactory at 0.82 and 0.79 for each of the two scales, respectively.

4.4.1.1 Qualitative Data

The collection of qualitative alongside quantitative data, in evaluating training interventions, is recommended as a means to gain more in-depth insights into both the impact of training and factors associated with its effectiveness (Clarke, 2002). It also offers a means to triangulate findings from a range of differing sources, thereby strengthening the validity of findings (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994). Semi-structured interviews were therefore undertaken with a subset of the 53 individuals from which baseline and final sets of measures were collected from the 3 training programs. In order to randomize the selection process, an individual with no prior knowledge of the project was asked to select 20 names from three lists of training participants representing those that attended each of the three training courses. Fifteen of these individuals were willing and able to take part in the follow-up interviews 6 months following the training. Interviews lasted between 25 and 45 minutes and were held at the place of work of the participant. Each interview was recorded and shorthand notes were taken by the researcher. A semi-structured interview schedule (Appendix 1) was devised which made use of the critical incident technique approach (Flanagan, 1954). This minimizes risks of generic or socially desirable responses and focuses on identifying specific behavioral data. The interviews were structured so as to capture how specific behaviors, thinking processes, or attitudes which are associated with EI had changed as a result of the training. At the end of each interview, the researcher summarized key points covered in the interviews based on the shorthand notes and checked for a common understanding with the respondent in order to verify the data obtained.

4.4.1.2 Data Analyses

1) Quantitative Data. Initial tests began with examining correlations between all variables measured in the study collected at the baseline and 6 months later. This was followed by undertaking a multivariate analysis of variance using a repeated measures design (MANOVA). Time was entered as the subject factor name with two levels (pre- and 6-month post test) alongside the six dependent variables assessed in the study: three EI abilities, empathy, and the two project manager competences). Initial positive results suggested follow-up univariate analyses were necessary. The software programme SPSS for Windows (Version 15.0; SPSS Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

2) Qualitative Data. All interview tapes were initially transcribed and then analyzed using a semi-emergent theme approach (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994, Miles & Huberman, 1994). In the first phase, all transcripts were initially read through by the researcher and the process of coding was begun by initially identifying and categorizing data that captured training impact and effectiveness (Coffey & Atkinson, 1996; Creswell, 1998). In the second phase, transcripts were analyzed further to identify any key themes that were common across interviews and which were not covered in the coding frame. In the third phase, these emergent themes were then coded into broader constructs where linkages were present. In order to maximize the trustworthiness of the inferences drawn from the qualitative data by the researcher, coding matrices containing the data were then presented to two additional researchers who were not involved in the project. Data were then retained when there was common agreement on the inferences drawn, and where the analysis from across the interviews converged. Excerpts from interview transcripts were selected based on judgments from all three researchers regarding those that offered richer details to best illustrate the findings.

4.5 Results

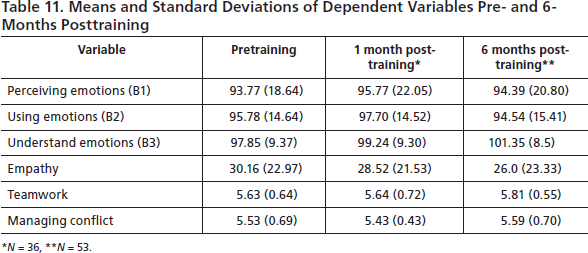

Means, standard deviations, and correlations between measures are presented in Table 9. The number of significant correlations between each of the three emotional abilities B1, B2, and B3, confirm that these abilities are related to one another within an overall construct, emotional intelligence. Initial MANOVA tests were performed to identify whether any statistically significant changes had occurred in measures of the dependent variables between pre- and 6-month post-training. Results indicated significant differences had occurred between the two time points, (F [6,47] = 4.45, p < 0.001). Further follow-up univariate analyses of variance tests were therefore conducted (Table 10). The results for the emotional abilities of perceiving emotions (F [6,47] = 0.08, < n.s.]) and using emotions to facilitate thinking (F [6,47] = 0.55, p < n.s.), failed to show any statistically significant changes. Significant effects were found, however, in relation to the emotional ability, understanding emotions (F (6,47) = 7.76, p < 0.01). Follow-up t-tests on differences between baseline and first post-test measures (1 month following training) showed no statistically significant changes in any of the three emotional abilities. Perceiving emotions, t(35) = –0.1, p < n.s.; using emotions t(35) = 0.21, p < n.s., and understanding emotions, t(35)= –0.38, p < n.s. Hypothesis 6 was therefore partially supported.

Significant differences were also found between the baseline and the 6-month post-training measures of empathy (F [6,45] = 3.96, p < 0.05). Follow-up t-tests on differences between baseline and first post-test measures (1 month following training) showed no statistically significant changes, empathy t(35) = 1.84, p < n.s. However, an examination of the mean scores obtained for baseline and 6-month post-test measures (Table 11) shows that empathy scores actually decreased over this time period. Hypothesis 7 was therefore not supported. Finally, significant positive changes were also found between the baseline and 6-month post-course measures in both of the project management competences of teamwork (F [6,45] = 4.34, p < 0.05), and conflict management (F [6,45] = 6.27, p < 0.01). Follow up t-tests on differences between baseline and first post-test measures (1 month following training) showed no statistically significant changes in any of these competences, teamwork t(35) = 1.31, p < n.s.; or managing conflict, t(35) = .06, p < n.s. Hypothesis 8 was therefore supported.

4.5.1 Findings From the Qualitative Data

The presentation of the qualitative data is organized within four broad categories that offer insights into both the impact of the EI training and factors associated with its effectiveness. These are as follows: (1) impact of the training on participants’ emotional intelligence ability of understanding emotions; (2) impact of the training on participants’ motivation to use emotional intelligence; (3) impact of the EI training on project manager competences of managing conflict and teamwork; and (4) factors associated with the effectiveness of the EI training.

4.5.1.1. Impact of the EI Training on Participant's Emotional Intelligence Ability of Understanding Emotions

There were many examples evident from the interviews with project managers that offer strong support for the key finding from the quantitative data analysis, that there had been improvements in the emotional ability of understanding emotions. A key impact of the training appeared to have been in encouraging participants to consider, in advance, the emotional impact of specific work-related scenarios and situations, and where possible, to attempt to plan ahead about how these might be best managed. Although not in themselves evidence of development of this ability, the qualitative data suggests a far more active use of this ability by training participants than had been the case prior to their attending the training program:

“There was one thing that came out of the training, about emotion being contagious. I think I recognize that now…I used to actually get quite worked up about something and think ‘Why is she not speaking to me? Have I done something wrong?’ and take it all quite personally. But now I tend to actually allow for it a lot more, I can understand why…and probably try and approach it in a different way. If I need something, whereas before I would've said ‘I'm not even going to talk to her because you know I must have upset her,’ now I understand what it is and say, ‘Well, I do need something from her and someone is gonna have to talk to her but in a different way.’ So I say, ‘I know you are really busy and trying to meet a deadline but I really need this in order to be able to continue with my work if you like,’ whereas before I would have tended to let it slip 2 or 3 days before I got the information from her, which would hold my work up.” (Project Manager male A1)

“Something that's been going on a lower level way for possibly a couple of years but it recently rose its head about 3 months ago…so I wanted to understand what I had to do in a situation like that…I thought about how I wanted to handle the situation, which I kind of planned out and put to my line manager…however, I had anticipated and the training reoccurred to me at each step of the way. Thinking about how the individual was likely to respond to the things that we were putting in place—which is not normally how I act—I normally just…deal with it and then what comes back can sometimes be quite a surprise. Whereas this time I was thinking, ‘I think it's likely that he won't want to do this—that he will want to propose something else.’ I thought, ‘He is likely to respond like this.’ I had a very uneasy feeling about meeting him, I didn't want to meet him and I asked my line manager if he would meet him instead of me. Not in despair of avoidance, but I had a kind of instinct surrounding it.” (Project Manager female A7)

“I really had to understand what might be making this line manager act the way she is towards her staff and I know that there's been incidents in the past…and it's not obvious, the person doesn't come across that way, and you just wouldn't expect it really…I do find it hard to understand why she would do that…so I don't know I have tried to understand what might motivate someone to act in such way to upset people so much…I haven't actually succeeded in changing the situation but I think I know much more about [the dynamics] that's causing all this.” (Project Manager female A19)

One of the salient findings to arise from the qualitative data was the extent to which understanding emotions was being actively used by these project managers, particularly as part of their role in relationship management:

“…We had a project that we've been working on—its in its fourth year. An international project with a number of partners and collaborators. And it's had kind of what you would say is a rough history of relationships. It's not an instinctive relationship…it's more a kind of structured relationship where we decided ‘wouldn't this model be good to try?’…But there's been a lot of disagreements along the way: how it should be resourced and how it should be structured, and one partner pulled out of it because they didn't like the way it was going. And it broke down. But some of the learning from the training I applied to it. It was quite soon after we had had the training and I was thinking about the need for clear boundaries and thinking about how emotions were driving things. We hadn't set it up contractually right. We hadn't written things down or been very clear with the partners about exactly what we expected of them and what they expected of us. There was so much breakdown in communication and lots of e-mails flying around about which, you know, you miss a lot about what we talked about on the training, tone, and meaning…And you can't see how people are responding or reacting. And everybody said, ‘There's no time to meet and we should pull the project,’ and I said, ‘No. We need to make every attempt.’ I suggested a face to face meeting and no one wanted to do it but I insisted that a face to face was really important because of the crisis…. it didn't fundamentally resolve all the issues, but we put practical things in place and worked together to plan how would we tackle the quality of relationships. It was quite rewarding to see people coming together and wanting it to succeed basically and moving from their position of pulling it…It was fantastic—absolutely fabulous, very successful.” (Project Manager female A3)

“…Some of the work that I've done since then has actually been working with third parties and partners, with some of them being quite challenging. So it's been useful to try to convey messages in a positive way so we end up with the best end result…trying to understand how my actions and body language can either help or detract from what we're trying to achieve.” (Project Manager male A12)

“…Setting up this program—I mean it's a huge program—it's a lot of money and we have ten pilots all over the country now. Very quickly literally within 2 months, we had to write a business plan for the next 3 years. And certainly it really meant that we had to establish trust very early on, and I thought, ‘Well, probably the best thing to do is visit them…[I said] ‘I just want to sit down with you for 2½ hours, 3 hours, whatever time you've got, and you just tell me everything you can’; and that created a kind of quality to the relationship…I think that, yeah, the relationships are based on trust and that trust was about sitting down and kind of going to their location.” (Project Manager female A19)

“One quite interesting project where…I was working for lots of different people…and I guess I played different hands with each person…and how just being really aware of where I was with each person and working on each relationship made a massive difference. I guess I'm much more aware of the emotional situation and this has had a massive effect on how I'd be dealing with people. Certainly when they do me a favor as well, and its beyond their job description, certainly…really just understanding how the other person may feel…‘not another e-mail from him,’ which I know a lot of the time people would be thinking…so I'm very very mindful now of how my requests may influence things…and work so that the relationship stays good and they are still willing to help me out. (Project Manager male A5)

“I'm generally known as being fairly open-minded, and what we're trying, working with a particular client, is to demonstrate that in terms of being open-minded. To listen to their problems, thinking through all kinds of issues, the priorities that they have. Before we then try to find a mutual solution. It's a difficult balance because sometimes we have the representation without responsibility, or the power to actually agree on something. So quite often it's just trying to listen. Trying to keep the balance without giving away anything. But actually bringing that back to the main organization as a potential difficulty with some potential solutions and trying to agree so that negotiations on this side can work. It's actually been something that has been quite difficult in the last 6 months but I do feel that the training has helped me to improve on that.” (Project Manager male B6)

4.5.1.2 Impact of the Training on Participants’ Motivation to Use Emotional Intelligence

A major finding to emerge from the qualitative data was that attendance of the training appeared to have some impact on these project managers’ motivation to use emotional intelligence abilities. This seemed to occur in a number of ways. Gaining an increased awareness of emotional intelligence and how it may influence leadership and management within projects may have provided a means for directing cognitive attention to use knowledge and skills in this area. This included a heightened awareness of the need to address the emotional impact of work situations and a consideration of strategies for doing so. For some, this also involved a far more personal shift in how they dealt with emotional situations arising in the course of work:

“But what you left with, is the kind of emotional situations that everybody kind of has in their own particular way, and struggles in this area in their everyday work. And then if you don't tackle them, they don't really go away; so I think I learnt a lot about how you need to manage the emotional part of situations. To look at ways of talking things through with colleagues. So I think that's what stuck really.” (Project Manager female B4)

“Ah, the main fact I really brought from it was that emotions are the one thing which really aren't discussed at work and how they almost go completely ignored. Although learning from it they are perhaps, fundamentally, the most important things that humans endure, and can kind of make or break an organization…certainly they can either add to or detract from a successful team or department.” (Project Manager male A8)

“I think it's become much more visible and palpable to me now in all kinds of situations I used to think which is probably what attracted me to the training in the first place; that I had kind of always felt that I was quite good at gauging the temperature in terms of morale, moods in the workplace. I would have thought that I picked up on those very quickly and quite early…But now I kind of feel after that training that there is a lot going on under the surface for a lot of people. And how some people have difficulty with expressing that. But now what I do see very much is our reluctance at times to act, which is very interesting, but not always good.” (Project Manager female B13)

“Ah, I definitely am a lot more conscious about emotions and being able to be quite upfront about that and saying, ‘Look we work in an incredibly emotional [arena]…’ and, I kind of see it all a bit more clearly now, and I guess there's a larger awareness in general that does affect me on a day to day…” (Project Manager female C7)

A number of training participants were able to identify specific situations that occurred since attending the training where this increased awareness of emotional intelligence caused them to do things differently:

“There have been staff situations, in large meetings where you realize that the dynamics aren't going that great—it's a bit anxious, and you think about what your role is in intervening and whether you should or shouldn't, and how you should tackle it. What the best way? So although what the training has taught me is that you kind of need to prepare and you actually need to be able to think about these things in order to be prepared.” (Project Manager female A7).

“[A colleague was] giving a presentation on a very key piece of work to a critical deadline…and I felt that people's anxiety levels had been building…and it was very badly done…in terms of communicating the message…And it started to deteriorate—he didn't pick up on how badly it was going down…I realized the situation was deteriorating but there's 30 people in the room, including managers…the staff were being very negative and unconstructive about it…and asking questions that weren't helpful…And I remember picking up on the discomfort, feeling uncomfortable…and thinking I need to try and alleviate the situation; to intervene in some way.” (Project Manager female B11)

There was also some evidence that the structured skill sessions on the training program played a role in increasing these project managers’ self-efficacy in being able to deal with emotional situations. For some, this was communicated by suggesting they now felt more confident in dealing with emotional situations which previously they might have avoided:

“Ah, I think just the way I deal with big groups, I was always, well it was a new group and I'm quite shy. I tend to just kind of go in and sit, and wait to hear everybody else…and I was the center of attention in one of the meetings…I actually had to give a speech and it was quite good although I was still a little nervous…so now in meetings I actually try to suggest ideas and get conversations flowing…And when there are meetings with people more senior, I have been trying to put myself to the front a bit more.” (Project Manager male B2)

“On a very personal level, it is more acknowledging that if I was feeling in a particular way, to actually go with it, rather than just say ok and just ignore how I'm feeling…and if the emotions persist, to act upon them, which is something that I've never done before. And I've taken a very different slant, which means that I'm willing to get myself into some confrontational situations or in situations where I perhaps have never been quite so bold or brave. So I guess it's really helped, in a way it's developed new thoughts…giving me a lot more confidence in myself and what I'm doing and thinking…also in terms of having a conflict with a member of my team I actually stood up to and really really taking it forward and not backing away from it despite its being incredibly uncomfortable and difficult. Taking that step I feel better if I actually move on what I'm feeling rather than sort of stand back and cower behind my emotions.” (Project Manager male A5)

Although the data did not suggest any improvement in terms of development of the two emotional abilities, perceiving emotions and using emotions to facilitate thinking, the qualitative data did suggest that these abilities were being used by project managers. The motivational aspects of the training program may have impacted the performance of some emotional abilities even though there was no evidence for their development. For example, in relation to perceiving emotions, there was some indication that training participants were more aware of body language and how this might offer insights into how others might be feeling.

“How people react to what other people are saying, not just their voices but also the way they were physically reacting as well…and sometimes when they are under pressure, when they are trying to negotiate something, when they weren't getting what they wanted…I mostly have to deal with handling people who are not interested in what you are saying, and trying to just work ways around that, and kind of trying to negotiate their feelings…” (Project Manager male B2)

“Body language, I have become very much more aware of that now and I have spotted it in lots of places, and if I see people copying stuff I'm just more aware. I don't think it changes how I read the situation but I'm definitely more aware of it.” (Project Manager female B11).

“This member of the team who came to me, I mean I could kind of read the situation from how he was, and I actually went to him and I said, ‘Are you ok? Because I'm not really sure that you are.’ And I guess I felt prepared to be able to deal with that situation if you know what I mean, I didn't want to upset him, I just said, ‘you know, let's try and work this through…’ I think it did allow us to chart a plan…so I guess it allowed us to plot a way through that situation.” (Project Manager female A19)

Also in terms of perceiving their own emotional states:

“I guess it gave me a measure of the other person, to say, ‘Look, I'm feeling terrible my motivation has disappeared…’ I was honest, at least I won't go back to where there would be a situation now or in the future where I wish I'd said this or that, wish I had explained how I felt, or expressed myself fully…in a way if you don't speak your thoughts then they just stay inside and then tend to be more self damaging rather than if you are aware of them so that you can move on.” (Project Manager male A16).

There was some indication that a number of trainees were far more aware of their emotions and appeared to be more consciously making use of this knowledge in relation to decision making:

“I think definitely just acknowledging that my emotions at work actually exist, that's something I had always tried to almost remove except for the positive ones. But I think it's me acknowledging the negative ones too that's really the main difference. I do have rubbish days and some days where…I think they're the days not to make decisions or to avoid certain types of tasks…so sometimes having a stronger knowledge of how I feel and knowing how to apply myself more effectively to certain tasks that I've got I can just get a remarkable amount of things done…” (Project Manager male A5)

“The meeting went very badly and, probably very uncharacteristic of me, I was virtually silent the whole way through which is not my style at all. So when we came out of the meeting…and it was very distressing…I felt it was kind of left opened ended and a bit unsatisfactory so I tackled the manager about that, tackle isn't the right word probably, and we disagreed fundamentally about the way it had gone and the way that we wanted it to go forward…and it was playing on my mind and actually I don't feel good that it hasn't been resolved, so it's kind of left in the air, I'm not really happy about it…so I'm left with the decision about whether to act, which is really about dealing with how I'm feeling…” (Project Manager female A7)

The processing of emotional information here also seems an important catalyst underpinning problem solving. This includes a focus on how individuals might change their own behaviors in order to deal with particular relationships in the future. Emotions, combined with the abilities of emotional awareness were therefore intimately associated with the process of critical reflection for many of these trainees. Specific examples were identified of emotionally driven problem solving as part of critical reflection that led to theorizing about how to improve interpersonal relationships:

“…It's not a complimentary one to me but I've unpicked my behavior subsequently. I had a meeting with someone from outside the organization and we were going to talk about strategy. We were all working on a common project with different elements of that strategy and I thought I was meeting this person to talk about our alignment so we were all getting the same messages even though we were coming from different departments if you like. This person proceeded to interrogate me and interviewed me about the work that I was doing. I could see my body language was becoming like this, I was moving my eye contact away, I was turning away…I was very defensive…so I'm thinking, ‘Why we've got all this interrogation coming my way? To fill the space in terms of what you haven't done? But I have to admit that I did not handle that situation well. I recognize my behaviors were defensive…when I am responding in a defensive way that's impeding my cognitive ability to deal with the situation and my feelings at the same time…Subsequently I thought of the strategies—you know: I didn't have an agenda for the meeting, I didn't know this person, the agreement was not there that we'll be talking about, they came on in a hierarchical way to try to impose something even though we were equals so, I was unassertive and I'm really surprised because I'm really an assertive person and I became unassertive. But I analyzed it and I know I'll have some strategies the next time.” (Project Manager female C9)

“I'm actually conscious sometimes of not trying to make the effort, and that…it actually takes a tremendous amount to match reasoning with the emotional stuff. It was easier to say let's forget it, let's call it a day. However realizing why I felt the way I did a lot more, I went ahead and took that decision. And I've been proved wrong because (the person) after one meeting was wonderful.” (Project Manager female A7)

Examples were also found where trainees had drawn upon their emotional states to reflect upon their own behaviors, and how these may have either positive or negative emotional impacts within their projects or teams. Importantly there was a clear focus found here with trainees considering action strategies that were associated with more effective emotional regulation:

“It's difficult to try and remain on a professional play level field. I won't go into any details but I have had some quite difficult situations personally, and this affected my behavior and my mood at times. So I do find myself sometimes consciously trying to switch from being me, to walking into a room as the calmed professional. Oh, I think once or twice yes, I've been a bit ‘short’ with people, but I'm generally more balanced when I'm actually with a client. With the team I work with, sometimes all that spills over, and that's inevitable. I can't pretend to switch off all the time. But I do feel with the people that I work with I've got enough trust and they've got enough trust in me to discuss things if needed…Yeah once or twice the language can get a bit colorful which is a way of my letting off steam.” (Project Manager male A12)

“There was conflict with a partner, [they] were seeking to change an agreement that we had made, and which had a potential impact of £ 700,000 of business for this company…and again trying to negotiate through that conflict, trying to remain calm, trying to remain definitive about what we're trying to achieve…I wouldn't normally lose my temper but I have actually been known to become quite assertive at times in this kind of situation…and I think maybe by remaining calm, with that level balance, that did actually help a lot.” (Project Manager male A8)

“I suppose it's one way of looking at it, because instead of looking at a situation and stressing, you can actually understand what's causing that situation and say to yourself, ‘I'm not gonna let myself get stressed by it.’” (Project Manager male A1)

“Yes, I have had a very difficult situation where a colleague has behaved very defensively but has tipped into aggression, as it often does when people are defensive…the person I felt has been incongruent…so I was losing trust very rapidly with that particular person…my instinct when I saw the person was to run away. It was a very powerful physical instinct as the person approached me…My feeling was to move away, physically move away or reduce eye contact. I was conscious of my behaviors and I worked very hard to mitigate against them…” (Project Manager female C9)

4.5.1.3 The Impact of the EI Training on Project Manager Competence of Teamwork and Managing Conflict

Emerging from the grounded analysis of the qualitative data was evidence that training participants had been using various aspects of emotional intelligence within the areas of communication and teamwork. Some were evidently far more aware that the way in which they communicate can have an emotional impact on those they work with in projects, and that this could potentially have both positive or negative impacts:

“Actually talking and dealing with some of the hard issues. That we are actually giving hard messages to people and some of the people that I work with. It's become easier with that kind of understanding and practice about how to convey some of the difficult messages about performance, and I think some of the actions suggested, about how to convey those messages in such a way that they will have positive emotional impacts rather than negative. I think that was actually very useful.” (Project Manager male A8)

“…I think if I've learnt anything from the training is this notion of how you contribute in a good or a bad way to the kind of the situation that's goes down. So you can actively intervene to try and move it, shift the mood or the emotions. I mean emotions are strong, I'm not an avoider. I can deal with conflict and I'm not afraid if someone's emotional. But I think now its not as invisible as it was, and so I know for a fact that round the room everybody has got something going on and how something might be received very differently. So sometimes you have to manage that, and think about the perceptions and how it will affect people…and change the mood if you can.” (Project Manager female C9)

“Yes, well, I think a lot more. I've been doing that since the training because I suppose that if you internalize a lot of what you imagine emotional intelligence to be…and I think what I've learnt is that actually you can take it much further than that. You can actively use it to improve situations. I think on a low level there are probably interactions all the time where you can try to understand where someone is coming from. We're not the best communicators entirely, we're kind of head down and very busy. So people would come up to you very abruptly and say, ‘Have you got this, have you got that,’ there are no niceties around that. So I suppose I have tried to kind of work with that.” (Project Manager female A7)

“It's really that communication stuff, I think that's what I generally try to focus on, because I came from a technical background. I try to actually set that aside when I'm talking with people and not lose them about IT. And [the people focus], that's really helped me back out of some potential difficulties. To actually try and think, what's my audience? Who am I talking to and what kind of level?” (Project Manager male A16)

This increased awareness of the role emotions play in project management was also found in relation to how some project managers thought about improving teamwork:

“…I see (EI) as an extra tool to help me get by…even in the sense of, you know, making a team happier…I'm currently working in this project where I've been basically [put] into another team…I think we can just organize this whole team much better because everyone is flat. No-one is communicating. It looks really miserable. I'm trying to create a team, people working together, and they say, oh that's a great idea. So now that's fundamentally changed the whole engine dynamic…I guess I'm just more aware of how emotions really, really play a part in the success. People would be doing the same work, the same stuff but because their emotions are different, they would be doing their work differently…because if you are unhappy your mind is not where you are…it's somewhere else, so you make more mistakes…I certainly do…Just acknowledging I feel [lousy] and that's ok so it's not even about it's all happy. It's great, it's more about honesty, that sometimes things are bad you know its worth talking about.” (Project Manager male A5)

“My background is in engineering, and I did a lot of early work in logic…I like logical systems, I try to defeat people logically all the time and it never works. I tried to set up systems. I'm quite good at enforcing them, which is basically my job, preventing things from getting too chaotic. But I think if you are very much aware of the emotional currency in a team, especially in a large organization or several organizations together, it actually helps you separate out from the systems. I think that's given me a greater clarity…and just being able to say, OK guys, this particular issue is about how we get from A to B, progress reports, or whatever. Let's get focused on the task and then we can also work on whatever issues that come of that in terms of how you're feeling, and I think that's how it helped, It has given me great clarity.” (Project Manager female C9)

This also included project managers attempting to be more aware of how their team members may be feeling, suggesting some use of empathy:

“This is a vulnerable person that's just started in the team. I've got a long-established team. We get on really well. We've grown to be personal friends, and there are high levels of trust and I tried to put myself in the position of somebody trying very hard to break into that and be accepted into the group. You know, be part of that team, and this person has a high level of skills. The skills aren't in question. It is [the] other [person's] ways of operating, coming from a different organizational culture…So I tried very hard to put myself in that person's shoes, and this is not like another [sector's] processes. We've got business processes. We have to sell our time. We've got to count every minute of every day. And so I had to really work hard to feel what that must be like and to put the effort in to building the relationship.” (Project Manager female C7)

“Yeah, I identified someone in the project. This is someone who has moved from central government to local government…This person now reports to me and that's an incredible change, and this guy, he just hasn't got there yet…But there are all kinds of problems because he still thinks he is central government and of course the power shift…but I remember in the transition I thought he is just going to be traumatized because he's going from a very high position really to this absolutely hell leather crazy delivery boat…and I think he was actually very vulnerable…because he feels destabilized in some way…I was trying to arrange visits…He phoned me out of panic and he said, ‘There's no reason for you to come here…’ But I know that he's still really irritated at a deep level, and I have to guard against that and be more [aware of it].” (Project Manager female A19)

“Yes I probably do that quite a bit now actually…Yes, especially when I'm thinking performance management and, well, when I'm giving feedback…I actually do consciously think how would the person be perceiving that news and, to make sure that I appreciate how they're feeling. I think to some extent I've done that for a long time but I'm just more consciously aware of it.” (Project Manager female B11)

“…Well, I've been working closely with someone on a project, and, we had an issue. Both of us had an issue with one of the other people, much more senior on the project. And we got to the point where I think the issue is when you start to lose respect for somebody. You start to not empathize with them anymore. So my colleague was in quite a bad place about this whole situation. So I tried to work with her to find that core of respect for this person. We needed to empathize with where she's coming from and I think that's how we resolved it. We tried to empathize, sort of contextualize why she was behaving in that way…” (Project Manager female C9)

“…In terms of performance managing somebody that I actually worked with…I try to put myself into that situation and, yes, I try to guess how they might actually be feeling—how I can communicate and get across those issues…” (Project Manager male A12)

Given that the training program was designed around a specific focus on conflict within projects from which to analyze the use of emotional intelligence abilities, it was not surprising that many project managers identified how their skills and practice in this area had changed. Importantly these changes could be linked to the use of particular emotional intelligence abilities.

The first of these was understanding the emotional impact of situations within projects and how these might lead to relationship conflict. Recognizing this meant a number were far more active in planning how to manage potential conflict situations in order to manage the emotional outcomes:

“It's very structured about approaching situations like this and that was helpful to me because you've got to find your own way through it…You've got to find your own style, but the best thing was it actually encouraged us to plan and we did plan a very difficult conversation with this new member of staff…And it's fair because it offered the other person the chance to come back to us, but we've got the information beforehand, plan very carefully, and we shared out the roles. We were clear with ourselves who was chairing the meeting, and the air was cleared as a result…It was a very positive thing for everyone.” (Project Manager female C7)

Others were able to recognize how a failure to effectively plan had meant they were far less effective at managing the emotional aspects that then led to conflict:

“Ah, yes there was one actually, when we were doing a project and putting a conference together, and there was quite a bit of conflict in the team as to who should be doing what. And where the roles really weren't defined early on in the project that caused considerable conflict in the team…but I think as I've reflected on it, I was able to think, well, actually it's because we weren't being an effective team because we hadn't agreed some issues on that project. We need to approach it in a different way at an earlier enough stage.” (Project Manager female B11)

There was some evidence that a number of training participants were far more aware of the need to manage their own emotions in order to avoid conflict within their project teams:

“In my new team situation, I have somebody new who doesn't stick to the rules, who bends and twists, and I was quite angry with this person, who's had a lot of time off since she started…and I don't think I've got the full story as I was told some lies along the way…then when I discovered that I was being manipulated, I had my feelings that mixed up, genuine concern contrasting with this sort of anger, unimpressed that I had been let down…and then we had to go into this meeting…and I had to make an effort to manage my feelings so as to get to the end result.” (Project Manager female C7).

“I did have a conflict situation and, unfortunately, it was me putting forward an argument that wasn't particularly listened to…and in this conflict situation I did try various tactics, being extremely balanced and direct, trying to be positive. But ultimately I felt…being resolution focused rather than just kicking out some grievances and hoping for the best helped.” (Project Manager male A5)

4.5.1.4 Factors associated with the effectiveness of the EI training

When talking about their experience gained from attending the EI training, there were a number of instances where project managers referred to aspects of the design of the training that appeared to have had an influence on their learning. The first key aspect here was how the training had offered opportunities for participants to learn vicariously from others participating on the program:

“I found those situations very helpful, where you can observe and see how someone else does, and you can think, oh yes, that's a very good thing to try. So, in similar conflict situations, where you've got some difficult conversations to have with people, and I do that quite frequently in my job, I found the practice in a safe environment a very useful thing and looking to see how others deal with it…And it has been quite difficult for me because recently we had some very difficult conversations with [this person] so the training and the experience helped in building up my confidence levels to deal with that situation.” (Project Manager female C7)

“What was most interesting was watching my colleagues actually interacting together, I think I learnt more about them watching them doing the exercises.. I didn't have that kind of insight of them before, so in a way that was one of my favorite things…but all kinds of things, you know, about body language and stuff. I mean, I took a lot away, you know, about understanding behavior…I guess I wouldn't have planned how I'd be using different bits of information but I learned to look at a deeper level, more conscious of observing people's interactions together.” (Project Manager female A19)

The training also offered opportunities for sharing ideas from across the project management field more broadly:

“I did actually meet a couple of guys on the course that actually had some very similar issues and I think that cross fertilization could be built on because trying to work in a project management field, it's especially easy to get into a silo of where you are and what you're thinking. Some of the ideas the other guys were coming up with were very useful.” (Project Manager male B6)

A number of participants also identified how the structured, facilitated sessions contained in the training enabled them to gain insights on their own behaviors and how their emotions were connected to them:

“Well another thing sticks in my mind. You remember the exercise when we sat in a circle with blindfolds on and there was a rope in the middle. And then you videoed this and played it back to us. I was horrified to see that I was leaping in there and I thought I had got this under control over the years, stopped doing that (laugh), because I'm always (laugh), I mean I think that it's a good thing about me, being very spontaneous, but it can be a double-edged sword. And I wish I was a bit more reflective and made more measured decisions. It's made me more conscious of that.” (Project Manager female C7)

“I particularly enjoyed the role play sessions that we undertook, where we had to play games and adopt particular roles and the opportunities to feed back. What was very interesting to me was the videoing, that was very, very powerful to look at how people interact…Because I was blindfolded I didn't realize how many people just sat out that activity. In my video I saw I was quite in there—someone that's always in, and we just do it without thinking…And I thought, my goodness, there are a number of people in that scenario that either were disengaged from it, or for whatever reason—being uncomfortable or not important enough for them and did not engage in that activity. I just began to reflect on that, just because I'm comfortable doesn't mean that everybody else is seeing or reading that situation.” (Project Manager female C9)

There was also some indication that the use of specific exercises and activities, which were specifically related to the use of emotional intelligence abilities within a project management context, was also associated with supporting greater learning:

“OK one of the biggest things I took from it was kind of, ah, one of those things that is really sort of cathartic, particularly the session on conflict management where we have to think about a situation where we had experienced conflict in the workplace. How it kind of manifested itself, how we coped with it. And that sort of brought up some unexpected memories…Something which I experienced a long time ago in the workplace surfaced and that kind of atmosphere, if you like, seemed to prevail for a lot of people…When we were doing feedback at the end of the session people were like, ‘Me, me, I wanna do it, I wanna get this off my chest.’ Being in that situation when you are talking about an emotion and how you use and understand and control emotions kind of frees things up. The language I suppose, gives you that permission to speak quite openly and honestly. That was one of the most valuable aspects for me.” (Project Manager male A1)

“On the course, three of us had to imagine a difficult scenario to give somebody a very difficult message about something and I had to do that a couple of times recently…I often have to give very uncomfortable messages to people, so it was drawing on those particular skills…It was dealing with a [project member] who was very angry on a number of different levels about a number of different things and highly critical of things, and I actually chose to say nothing. It was a judgment—a judicious choice to say nothing and just let him speak and not interrupt him. What I chose to do was listen very carefully to his feelings and I reflected his feelings back to him. I couldn't promise him anything because it wasn't really in my power. It was all issues relating to things at a much higher level, beyond my limit, so there's no good [in] me saying well you know I can do this for you…So I just listened to the issues and tried my hardest to pick up the feelings and reflect those feelings back to him, and that actually helped, you know…and that was quite powerful. I mean at the end he said I'm not angry with you, you're doing a very good job—that's not the issue here—there are much bigger issues. It was actually about being in control.” (Project Manager female B11)

Of significance, a number of participants also suggested that EI development was likely to be an ongoing process and that the impact of training on its own was likely to be limited:

“[With] EI, you don't just leap in and suddenly you are an expert. It's a lifetime work and so the EI course, it's a 2-day thing…It's not just something fresh to me, it's something I've been working on my whole life, personal life, and working life, so you can't learn enough about it. I think it's so important. It helps me to understand what goes wrong in workplaces and in families and in personal relationships. Mostly you are just not enough aware of it yourself.” (Project Manager female C7)

“I think in a way you might have sowed seeds. I don't think 2 days can be quite enough to have a kind of an epiphany. But you know, seeds have gone in and I notice these ideas in everything else that I do. I then start thinking about and using the ideas relating to feelings…using them as a tool. Something additional, certainly when it comes to just being in a team, managing a team, seeing how the team operates. Even advising how things could work much better by bringing these things in the open. It's the invisible aspect of work.” (Project Manager male A5)

Relevant to this were the comments by a number of project managers that the wider social environment influenced how and if emotional abilities were used. The training had offered an opportunity for these individuals to focus on their own approach to dealing with emotions at work and within projects, and how this was also influenced by the organizational field of which they were a part:

“Ironically, I think the [organization], it's quite dead. It's very flat emotionally. The new team…seems to really acknowledge how people feel. But I think in the [organization], they're really bad at dealing with negative emotions. That's one thing that I've learnt recently from my own experience, but even people at more senior level here they're really reluctant to face difficult situations. One of my colleagues either exploits it or it is swept under the carpet. It's either a complete disaster or just ignored so there's no middle ground for dealing with situation. [The training] really has got me thinking about that.” (Project Manager male A8)

“I think it was particularly about the organizational review we are facing at the moment, how the organization is behaving around trust, and how the employer/employee relationship is maintained…I think that trust is quite shaky here and it has an emotional impact.” (Project Manager male A1)

“Well, I guess I had a few conversations with people. I think a couple had been about how there seems to be a lack of emotional intelligence here and I guess even a lack of emotional awareness. Many people, they are aware, they just don't really care. It's quite hard to know sometimes…Can you even teach EI or is it something that you just bring more into focus, rather than someone who just has no knowledge of their actions and their impact…which they might use to perhaps better their own behavior towards other people. I know how hard I find it and I think I'm reasonable, but I noticed sometimes just how markedly wrong I got things. On one occasion I think ‘oh no, I totally misjudged something.’ How could I have got it so wrong? So I think, I guess [the training] has certainly given me something very solid on which to base my thinking…but I don't think people are really willing to discuss their personal feelings. Perhaps it's too much—they are not willing to give that much of themselves away. Which is another symptom here, that emotions can't be shared, they're too dangerous.” (Project Manager male A5)

4.6 Discussion

Findings from both the quantitative and qualitative data suggest that the ability, understanding emotions, can be developed in project managers as a result of a 2-day training intervention. Importantly, however, the results suggest that this took place over the 6 months following training. Although based on a subset of the total number of training participants, the data analyses found no statistically significant changes in this emotional ability 1 month following attendance on the training program. Changes were, however, detected 6 months following training in the larger data set. Although not conclusive, the results are strongly suggestive that, whereas training may offer a platform to begin developing this specific emotional ability, additional factors subsequently play a role. The qualitative data offered some insights as to the additional processes that might be implicated. Analysis of the interview data suggested that following attendance on training, many project managers were more consciously aware of trying to understand and anticipate the emotional impact of behaviors and situations within a project management context. For some, this seemed to indicate that they were more intensively cognitively processing emotional information than they had been aware of previously. The considerable range of emotional scenarios and challenges arising from working in their teams and projects, appear to offer rich opportunities for these trainees to put their ability relating to understanding emotions in practice. The additional processes of problem-solving and reflection, associated with experiential learning on the job following training, appear to play a major role in enabling this emotional ability to develop further. This is very much in line with Clarke's (2006a) proposition that emotional abilities may develop through workplace learning methods as a result of “emotional knowledge work.”