2 PROCESS: DISCOVERY

>Designers routinely face design projects that are more and more complex. In particular, information design projects require careful thought, collaboration, planning, and a process that goes beyond the intuitive, gut-level, and sometimes solitary approach that many designers have been trained to use.

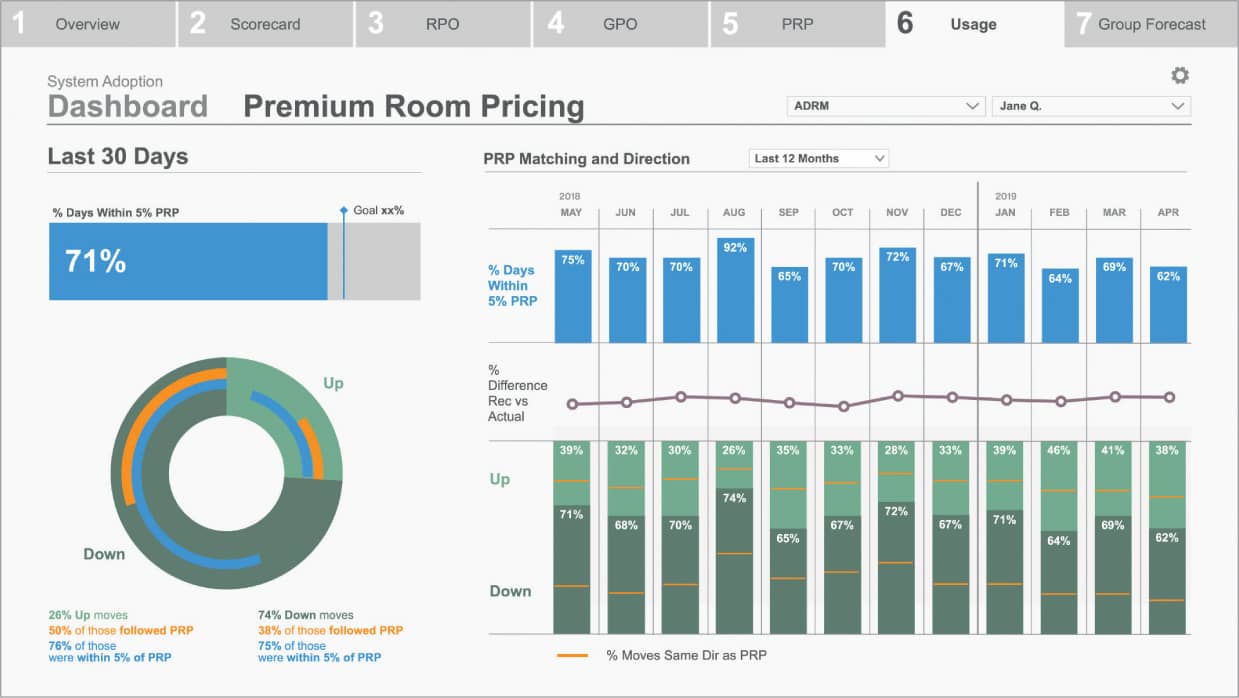

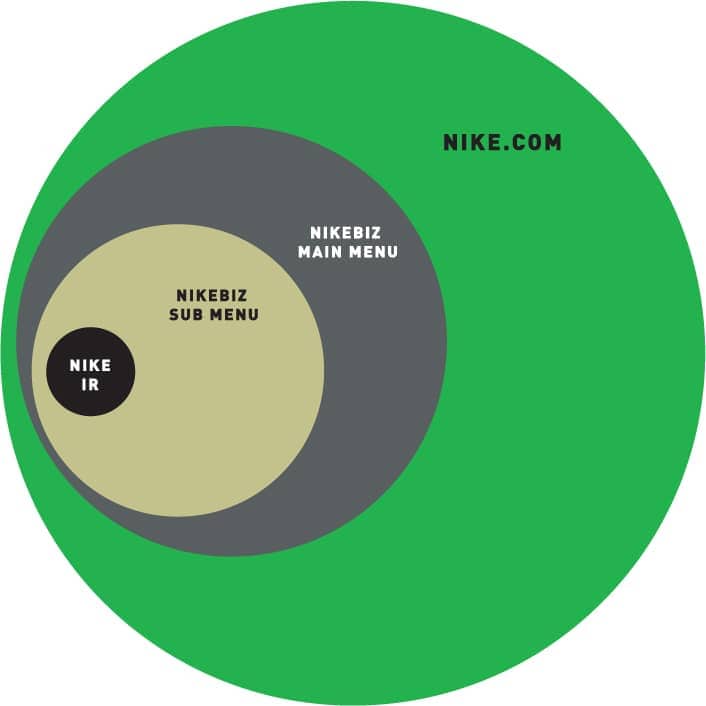

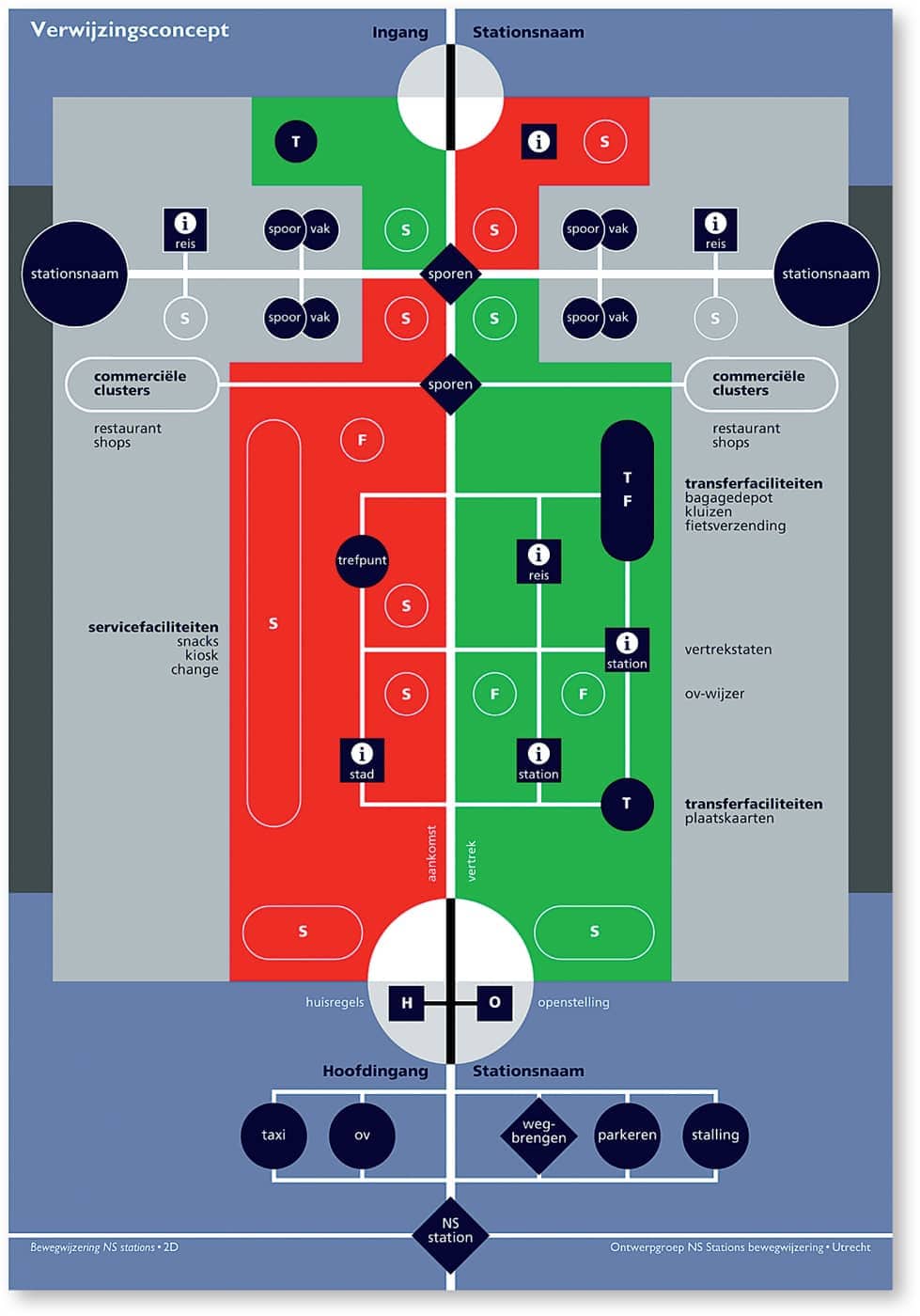

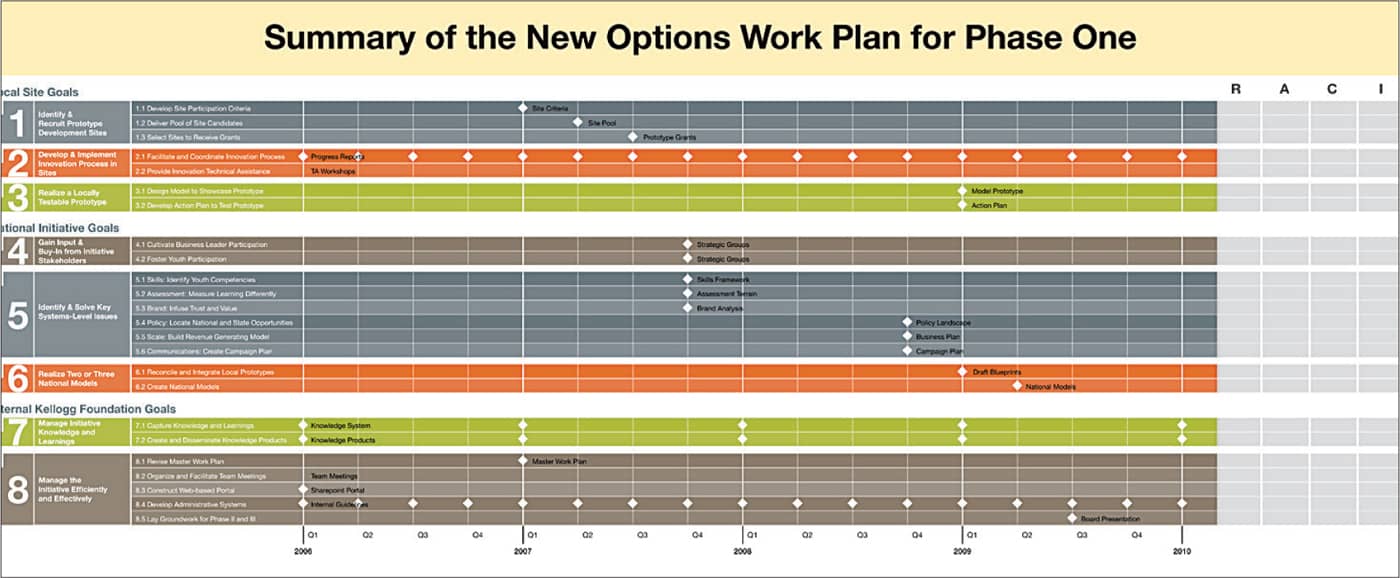

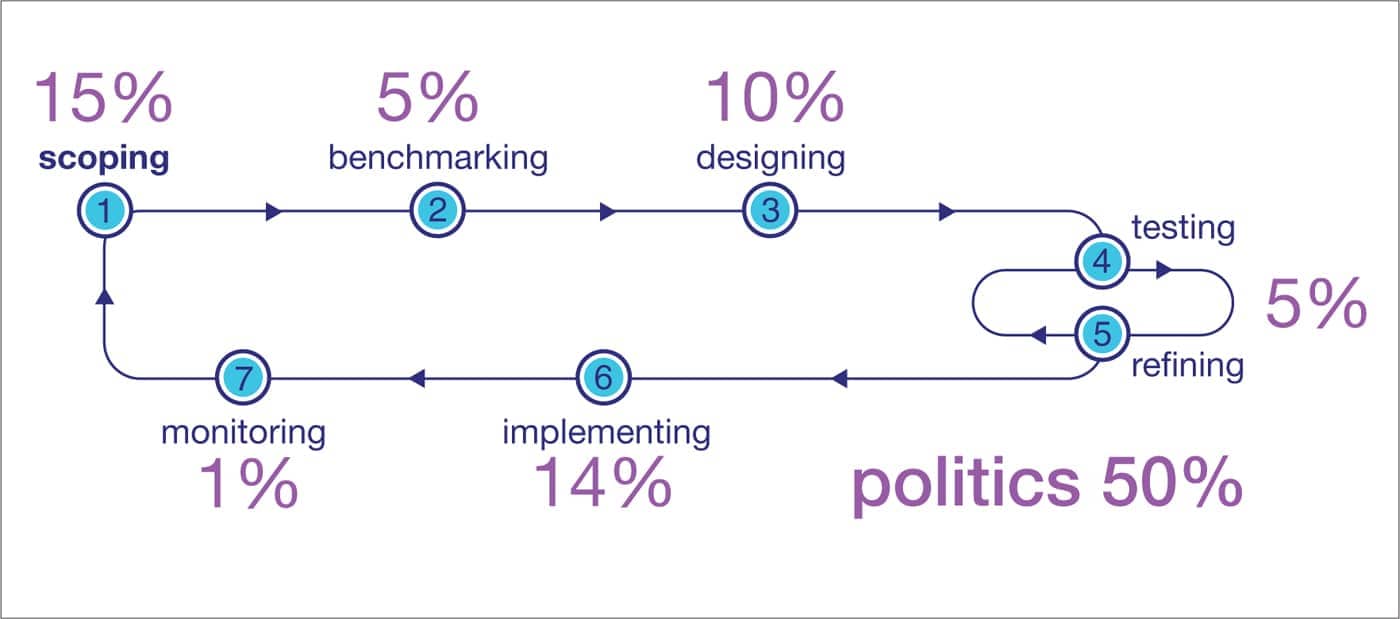

“We regarded it as unacceptable to say that a design might have worked but for the politics. Given the major role that political, social, and economic issues played in the outcome of design projects, we thought it important to develop methodologies that took account of these issues.” —David Sless Many factors that determine the success of a design piece are unrelated to the formal aspects of design but have everything to do with the context in which the design is created. More and more information designers find that to create relevant solutions for their clients, they need to find out about the inner workings of the organization, its politics, goals, and agendas. Why is that? First, by finding out what makes an organization tick, you’ll be able to offer smarter solutions. Second, by understanding the inner workings of an organization, you’ll be able to create the kind of teamwork, collaboration, and consensus with your client that you need to achieve project success. Understanding your client’s structure has enormous value, especially when there’s a complex hierarchy in place. What departments will participate in the project? What will their involvement be? Who has a stake in the outcome? A microsite design project for Nike Investor Relations needed to fit into the overall business hierarchy and web organization structure of Nike.com. This diagram was created to help the diverse client teams understand the navigational challenges. KBDA Client History 101. Have similar projects been undertaken within the organization before? Who participated and will they be involved in this project? Was the experience positive or negative overall? What were the roadblocks or challenges? How did the client measure success? Learning a little bit of background about what happened prior to your arrival can be quite illuminating and useful. Understanding your client’s internal challenges and decision-making methods allows you to be proactive in terms of both your process and the design solutions you ultimately present. Cultivate Allies. Who among your client team understands the project process already, and who can be educated about the process to the point where they will be your best advocates? It helps to make sure you cultivate allies both at the grassroots level of the organization and at the higher decision-making levels. Obviously, having great rapport and understanding with people at the highest decision-making levels will aid you greatly in obtaining buy-in for your designs. Developing solid relationships with the grassroots people in the organization can give you additional insight into the client’s internal machinations and can help you grease the project’s wheels. Who Wields the Power? The person who is the ultimate decision maker should be at the table for the kickoff meeting. This is critical. If the person with veto power isn’t present, you could spend weeks or even months creating a design solution that has no chance of being approved because, for example, the ultimate decision maker hates the color green. Be sure to ask at the outset: Is there anyone else who could swoop in and change the rules or nature of the project? Are there any other circumstances or an internal client agenda that could impact the project? Sometimes design projects require balancing the needs of different constituencies. For example, in planning a wayfinding system for a public transit hub such as an airport, commercial interests are balanced with travelers’ needs. (See case study on this page.) Mijksenaar Diagram the Process. Even before project work begins, explain and outline the process so that everyone involved gets the big picture. Make sure everyone working on the project, including your design team and the client team, understands their roles and responsibilities. Document the steps in the process so that team members can refer to it down the line. Who’s on the Team? Make a list of everyone’s roles, responsibilities, and contact information, including email, snail mail address (in case you have to ship something), and office and cell phone numbers. You can’t always assume that the project manager has all the info. There may be an emergency where the PM isn’t available. Of course, you’ll want to set up contact protocols. Most of the back-and-forth contact will happen between the two project managers (one on the design side and one on the client side). And while it’s true that you may not want the junior designer to randomly phone the client’s CEO just for the heck of it, you do want to make sure that any critical contact info is handy for the team in case of an urgent situation. “What Americans call politics, Europeans call bureaucracy. Ultimately it comes down to competing departments defending their own turf. Politics sounds as if it’s untouchable, as if you can’t do anything about it. But you can create change.” —Paul Mijksenaar Assign Point People. Who will be the day-to-day point person on your team and on the client team? You’ll need to make sure you’ve got people on both sides of the project to guide it throughout all stages. This work-plan diagram breaks down a project week by week to help the team plan ahead. Matter “Politics is about people’s interests. People argue for and define what is of interest to them materially and organizationally. People’s eyes will often roll at this unpleasant stuff called politics, but the reality is that it’s ever-present and will up and bite you.” —David Sless The Communication Research Institute in Australia points out that an inordinate amount of time in every information design project is spent in meetings, and on tasks related to process and project management. For a long time, the organization hadn’t been able to charge for this time. Now the method they use to budget for projects is simple: They go through all the technical and design specifications, figure the time that will be required, and then double it. Communication Research Institute, Australia The Timeline. Before you create the project timeline, find out about client expectations and make sure they are realistic. Determine which of the drivers for the timeline are truly fixed, and which can’t be changed. (For instance, the client is going on national television and the website needs to be up and running in plenty of time.) Of course, every client wants the project done yesterday, if not sooner. Most projects have a sense of urgency, which is a good thing. A healthy sense of urgency ensures that everyone takes the job seriously, and this means the work will get done in a timely manner to the benefit of the team, client, and end users. But try to see if you can separate the truly important deadline situations from false urgency. You want to set up the project in a way that will give you the best work within a reasonable time-line. Sometimes clients impress upon you a false sense of urgency and you rush to completion. You may not have quite enough time to do what you really want to do and may be forced into cutting corners only to find out that the deadline was based on something relatively inconsequential. Conclusion: The Water’s Fine. While it’s true that you can just dive into the project headfirst and figure things out as you go along, we don’t recommend that approach. A little bit of planning and setup, a clearly defined team, some knowledge about the client—all these things can really help the process so there are fewer surprises and pitfalls once you get down to the business of designing.Politics, Diplomacy, and Consensus

WHAT MAKES YOUR CLIENT TICK?

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES

OUTLINE THE PROCESS, TEAM, AND ROLES

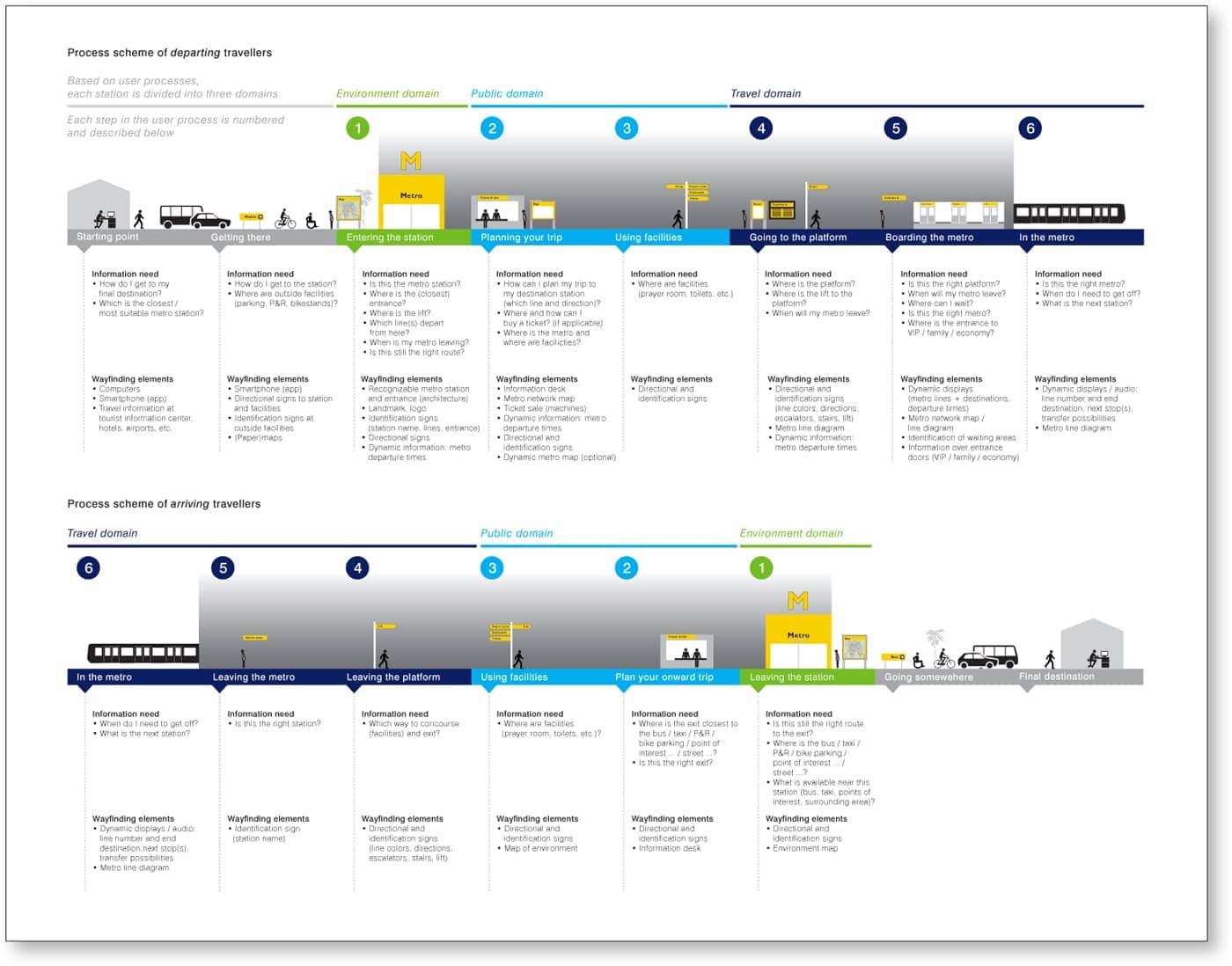

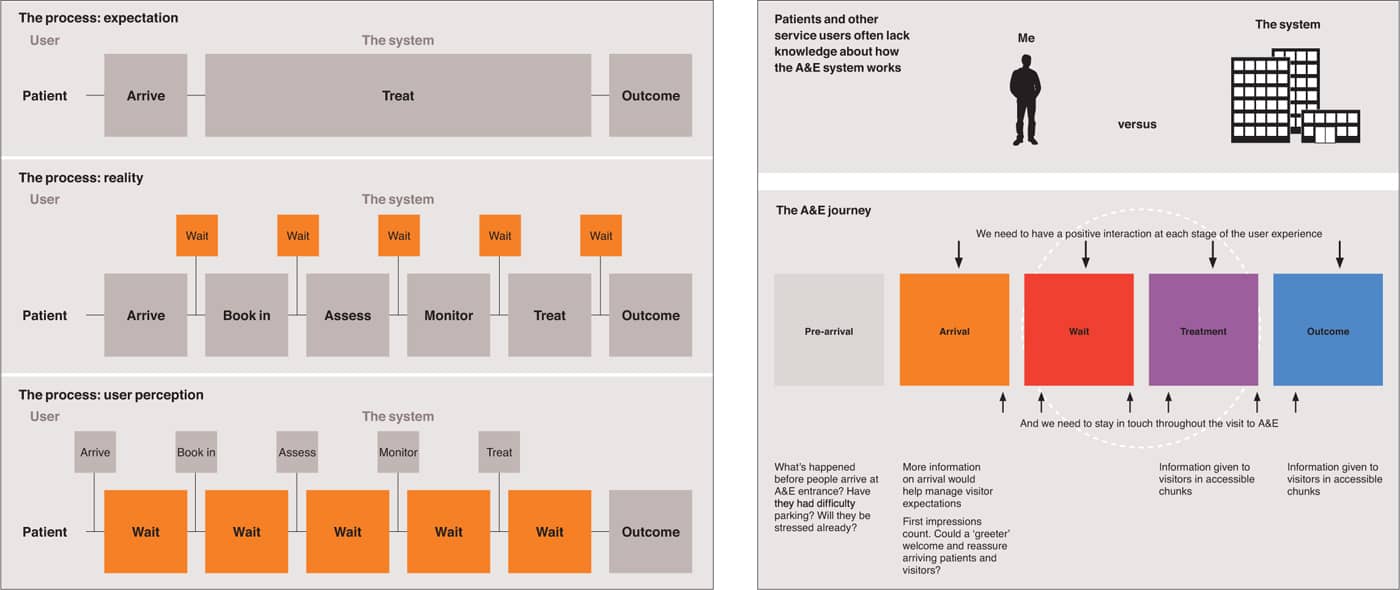

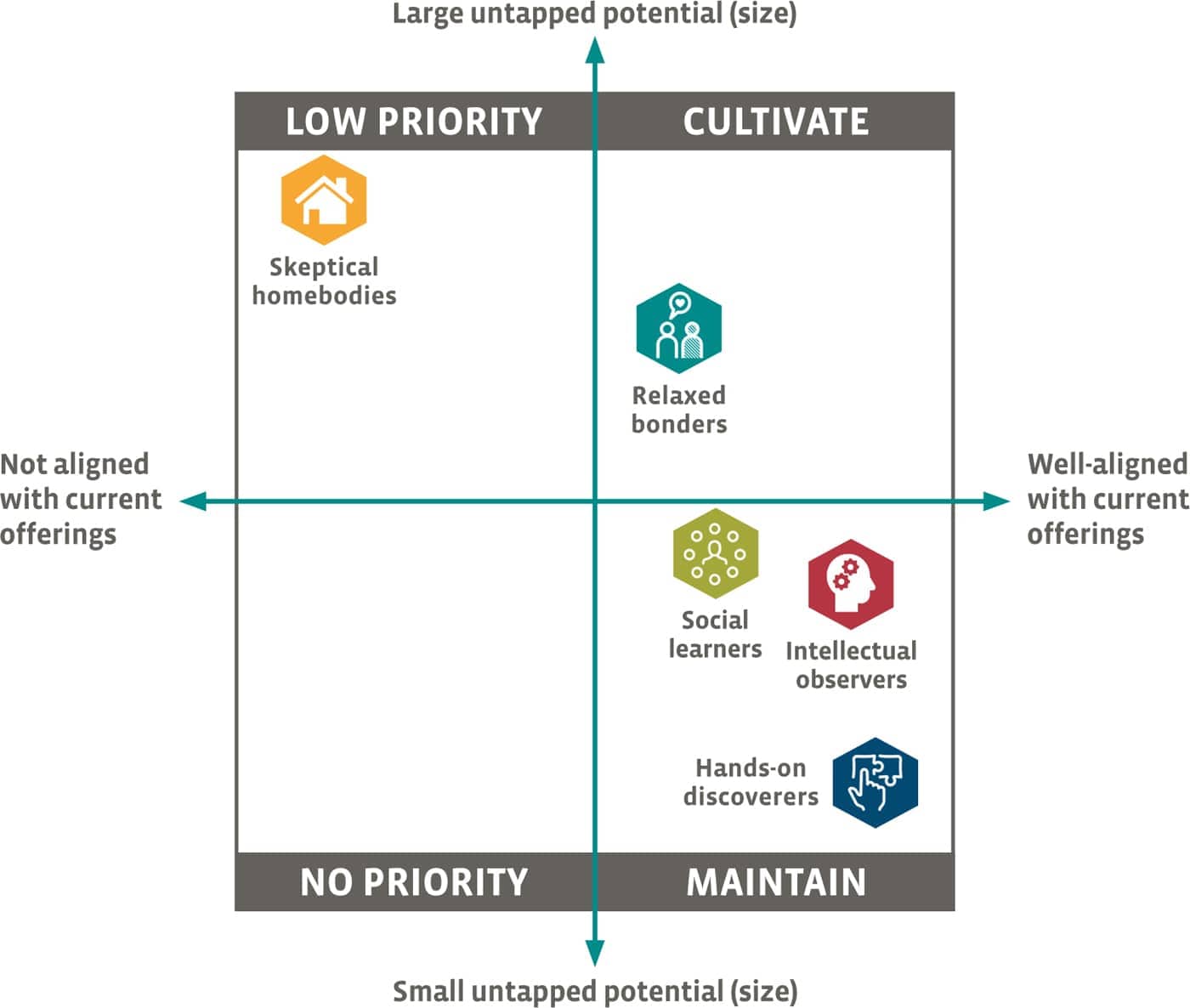

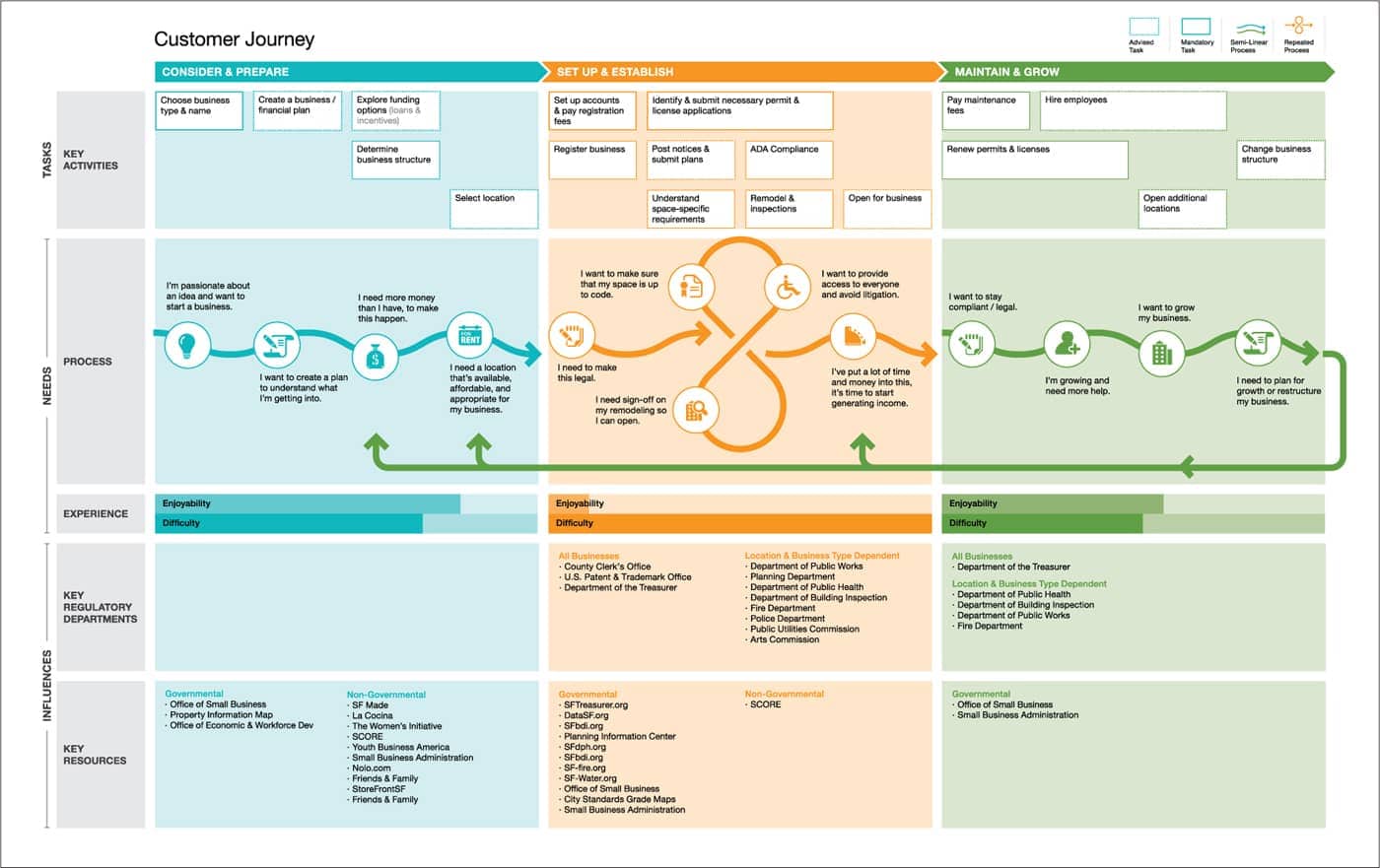

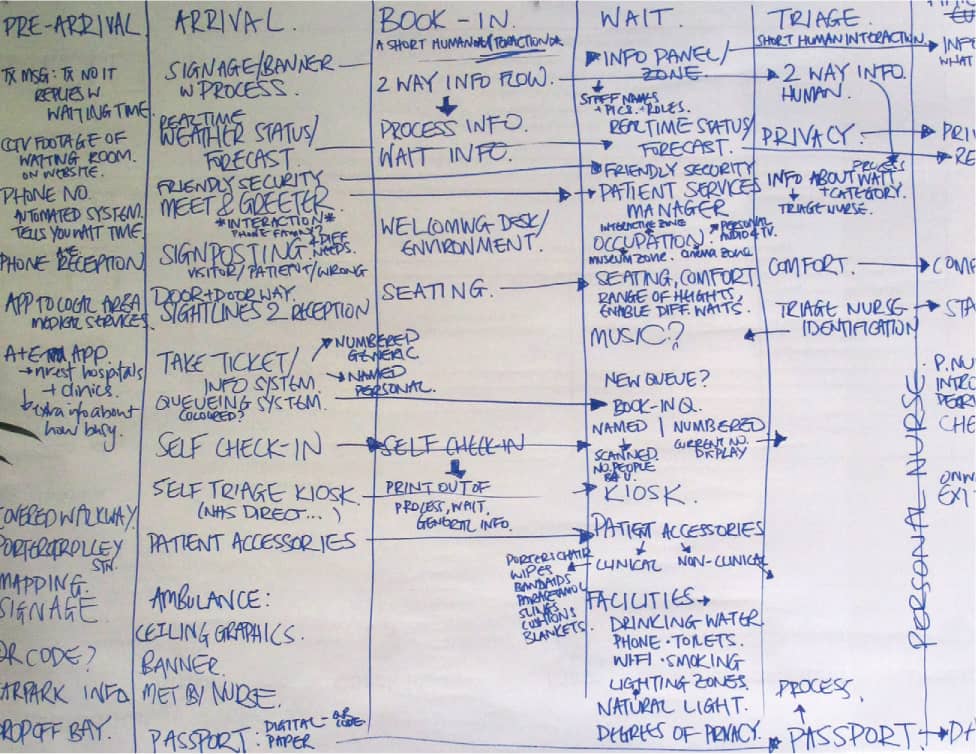

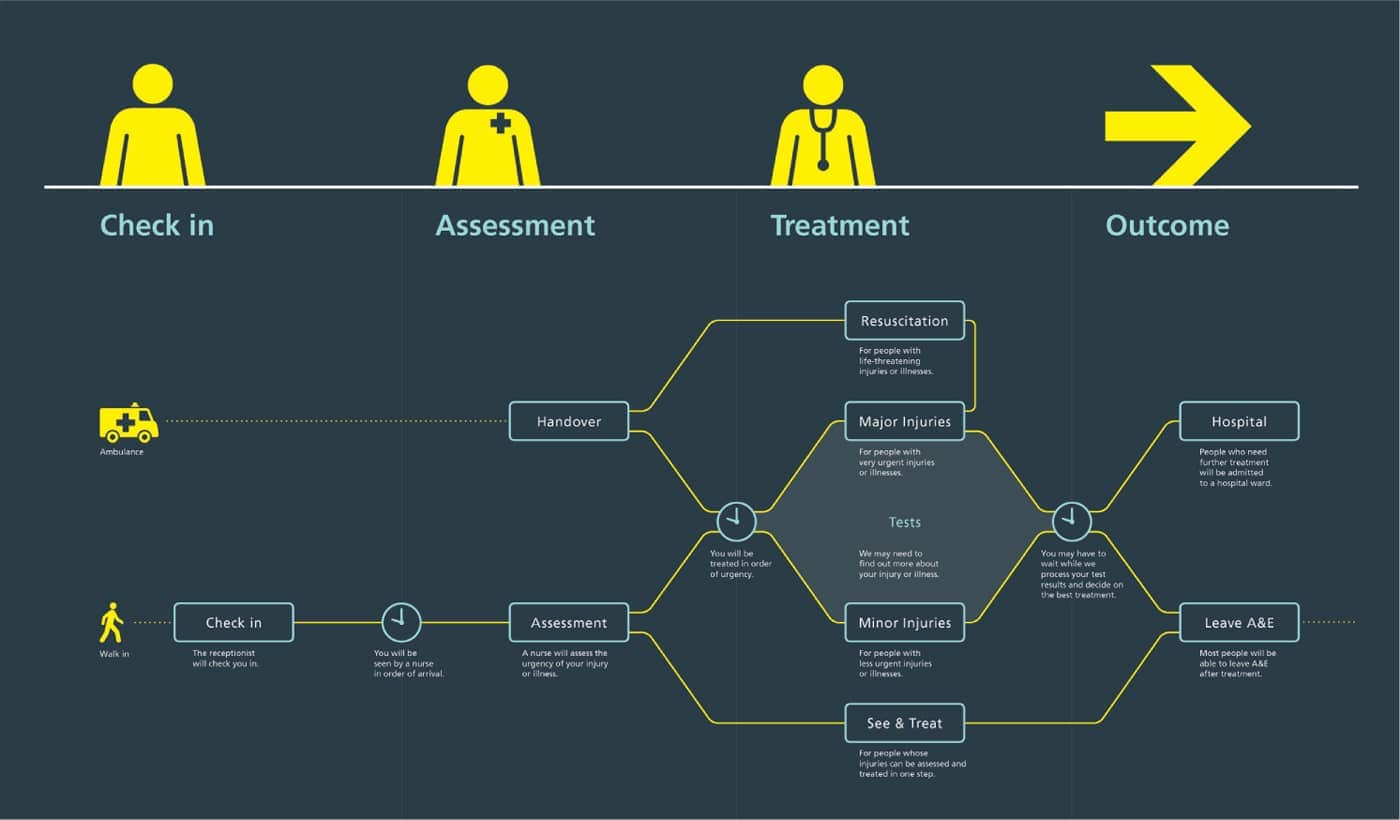

“You know you’ve been bitten by the information design bug when you begin to understand that the power of information design lies in the way it can be used to help people, to make their lives easier and better by providing serious, even life-saving communication.” —Robert Swinehart A critical requirement for good information design—whether it’s a medical app, a museum exhibit, a wayfinding system, or consumer packaging—centers on understanding the key audiences. As you help develop communications strategies, you’ll play a valuable role as a consistent advocate for the end user. An Authentically User-Centric Approach. Designers need to be on high alert to make sure projects aren’t being launched with out-of-date data, suppositions, or clichés about users. The most effective information designers begin every project by verifying these assumptions. To get truly valuable user insights, you need to: While designers have more options than ever before for understanding target users—it’s critical to understand that each research tool has its strengths and weaknesses. The field of user research is robust and demanding. To do it justice would require its own volume. (See Resources.) The nomenclature shifts from sector to sector, but in general, there are three phases of evaluation during any given kind of project: Front-end Evaluation. Some tools are incredibly effective in the “blue sky” phase of a project, as the team is beginning to formulate a plan. The team may want to better understand current customers or know more about potential customers. This kind of research is often used to explore how people think about and perceive a topic or experience. Formative Evaluation. Conducted in the early phases of design development, formative evaluation can test themes, text, graphics, and any other elements that comprise a project. Formative evaluation allows teams to measure what might be working and evaluate what should be further refined or course-corrected. (See User Testing discussion on here–here.) Summative Evaluation. Additional research and user testing is important for a team to evaluate the efficacy of a design nearing completion. This kind of evaluation is also critical after a design has been launched, so the team can evaluate options for subsequent versions and improvements. In planning a massive wayfin-ding project for Qatar Rail, the design team conducted a series of workshops with the client and the architects to map a typical visitor’s journey across three zones, from arrival, through purchasing tickets, and finally boarding the train. The resulting roadmap, which captured typical questions and concerns at every step, informed the final signage placement and design. Mijksenaar London-based Pearson Lloyd was commissioned to evaluate medical emergency departments throughout the U.K. Drawing on in-depth, on-site research, the team was able to map serious discrepancies in visitor perception. The team provided a road map for pragmatic improvements. (See case study on this page.) Pearson Lloyd/Design Council To inform the process of creating wayfinding graphics for a large botanical garden, personas were created to help designers meet the needs of several distinct types of visitors. The name, photo, demographic, and psychographic data brought each visitor type to life. KBDA In general, audience research is described as being qualitative or quantitative. Quantitative data (e.g., from surveys) can be counted, statistically measured, and reported using numbers. Qualitative data (e.g., from interviews) is observed and described. As mentioned, many different tools can be used during each phase of research. They are best deployed depending on the audience type and the nature of the inquiry. Specific research tools include the following: Audience Intercept Surveys. An intercept survey is a research method used to gather feedback on site. Intercept surveys are often used at destinations, or during events, to measure audience perceptions. Results from intercept surveys allow you to obtain feedback from target audiences while the information is still fresh in their minds. Questions can be both quantitative and qualitative. Online Surveys. Online surveys can let teams ask open-ended questions to capture qualitative input, as well as multiple-choice questions for more quantitative analysis. Online survey tools can help the team quickly assemble and visualize research results. In-depth Interviews. Whether one-on-one, or in small groups, researchers can engage existing or potential audiences to gauge potential interest or get feedback on a project. This is a qualitative tool, and requires thoughtful synthesis to deliver actionable insights. Ethnographic Research. Ethnographic research is a qualitative method when researchers observe and/or interact with a study’s participants in real-life environments. Ethnographic research was first used by anthropologists, and other social scientists doing fieldwork, in an attempt to fully understand as much as possible about a group of people, or even an entire society. One of the main advantages associated with ethnographic research is that it provides additional context, and can help identify and analyze unexpected issues. Because of this, it’s most useful in the early stages of a user-centered design project. Researchers need to be both empathetic and thorough to deliver true insights. Most importantly, they need to be highly disciplined and ethical to avoid any potential bias (and mistakes) in data collection and analysis. And just as there are a variety of research “instruments” for gathering user input, there are a variety of tools you can create to document the results and help keep them front and center for teams throughout the design process. User Profiles Keep Audiences Top of Mind. A user profile is a brief write-up of a typical user that captures specific personality attributes, desires, needs, habits, and capabilities to help the design team keep the ultimate audience front of mind. A user profile can be a composite, or representative of a typical user, rather than an actual real-world user. (See example at left.) Slover Linett, a Chicago-based social research firm that works with the arts, culture, and community sectors, uses a mix of qualitative research, quantitative surveys, and cocreative methods to help cultural organizations understand their communities. The firm’s team, trained in fields as diverse as anthropology, psychology, and public policy, often creates audience segmentation maps to clarify distinct attitudinal and behavioral audience types. Slover Linett If your audience encompasses many kinds of users, you’ll want to create a series of user profiles that reflect the range in audience types. Most projects require three to five user profiles. A single person on the team, such as the designer, the information architect, or the project manager, can create the user profiles. However, a group work session with the design team and the client team can be one of the best ways to generate a set of personas. Not only do you gather more creative input during a collaborative process, but the act of creating personas can be a great team-building exercise at the start of a project. The client team, especially at project inception, will generally know more about their users than you will. On the other hand, you, as the designer, will often ask valuable questions, and even question certain client assumptions. Making these user profiles feel as personal as possible (for instance, giving them each a name) reminds the team to consider each prospective user with empathy as important decisions are made. You’ll be surprised at how often clients and design team members will refer back to the user profiles throughout the project. There has been a great deal of research and writing done recently about best practices for creating user profiles (or personas). Sometimes the demographics (age, gender, and socioeconomic status) are less important than looking at the archetype, or psychographics (personality, values, attitudes, interests, or lifestyles). Some researchers feel the archetypal approach is a more useful tool for evaluating audiences aspirations, which can be valuable for evaluating products or services still in development, or on the horizon. (See example above.) Tomorrow Partners was asked to create an online tool that would help San Francisco-based business owners navigate the city’s complex permitting process. By meticulously mapping the typical process for the three most prevalent customer types, the team was able to parse the pain points for each. These insights informed the team’s proposed navigation design. (See case study on this page.) Tomorrow Partners Scenarios Show User Profiles at Work. User profiles (and personas) are like actors. Now that you’ve got your cast in place, you can start to capture what those users would likely experience as they interact with your project. Most frequently created as narratives, scenarios can relate to one specific task or they can be more general, evoking how a user might interact with a multidimensional experience like an exhibit or a service. In early development phases, scenarios can help teams coalesce around a vision for a new experience, while keeping audience needs top of mind. A customer journey map combines two powerful communication tools—storytelling and visualization—to help teams document and carefully consider audience needs. It maps the customer experience across multiple touch points, starting with the initial point of contact. Maps may focus on a particular part of the story or give an overview of the entire experience over time. Designers use maps to synthesize what they learn from interviews and observations. (Or, during field research, you can ask your end user to map out his or her own journey.) A good journey map accounts for the users’ feelings, motivations, questions, and frustrations at each touch point. The goal is to create a holistic view so the team can identify opportunities to enhance the experience. If the resulting visualization can convey the information in a concise and memorable way, it can help crystalize insights and inspire a shared vision for what’s possible. Journey maps can help teams focus on one type of customer or look at multiple user types. Teams might focus on existing customers or explore ways to target new prospects. A customer journey map combines storytelling and visualization to help teams document and carefully consider audience needs. This complex service design project started with on-site research and documentation that captured every step of a patient’s journey to seek emergency medical treatment. The map, continually refined during the project, provided guidance for ways to improve the user experience at each touchpoint, and ultimately became part of the communication strategy that dramatically improved outcomes. (See image below, and case study on this page.) Pearson Lloyd/Design Council This simplified journey map was created from real-time observation (see above). This refined version now helps patients understand where they are in the sequence. This has dramatically improved outcomes. (See case study on this page.) Pearson Lloyd/Design Council Journey mapping can sometimes be the most valuable aspect of a project. Because journey maps codify what are often disparate data points, they can be a tool for creating cross-department conversation and collaboration. Journey mapping can be the first step in building an organizationwide plan to invest in improving the customer experience—whether it be a targeted piece of communications, such as a contract, or an overarching system like the wayfinding in an international airport. By highlighting areas of friction, it can help answer the questions: “Where do we start? How can we make this better?”Defining Audiences: User Profiles and Journeys

KNOW YOUR AUDIENCE

A PHASED APPROACH TO RESEARCH

QUANTITATIVE VS. QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

REPORTING RESEARCH RESULTS: AN ART AND A SCIENCE

MAPPING TOUCHPOINTS PROVIDES CRUCIAL INSIGHTS

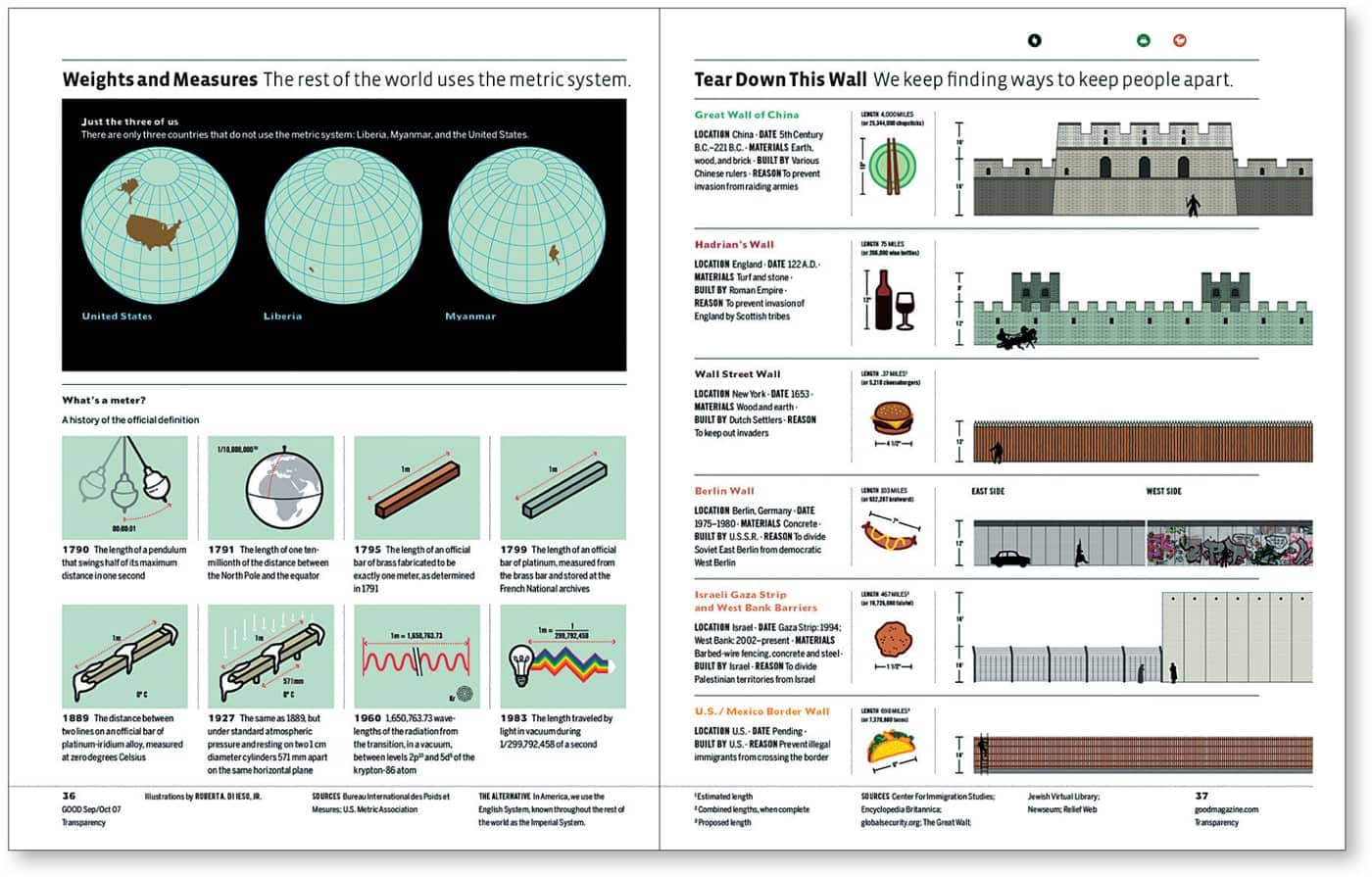

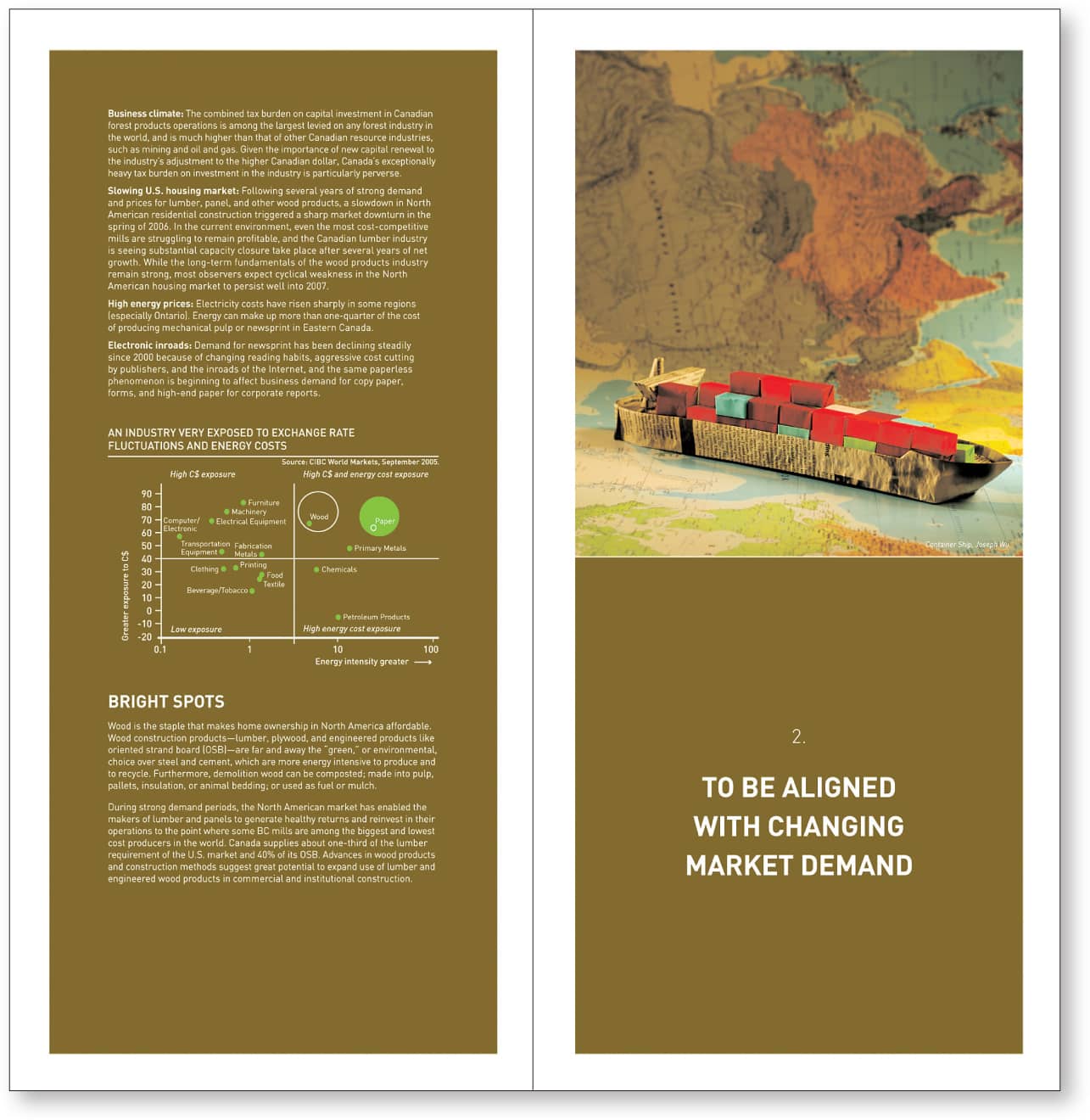

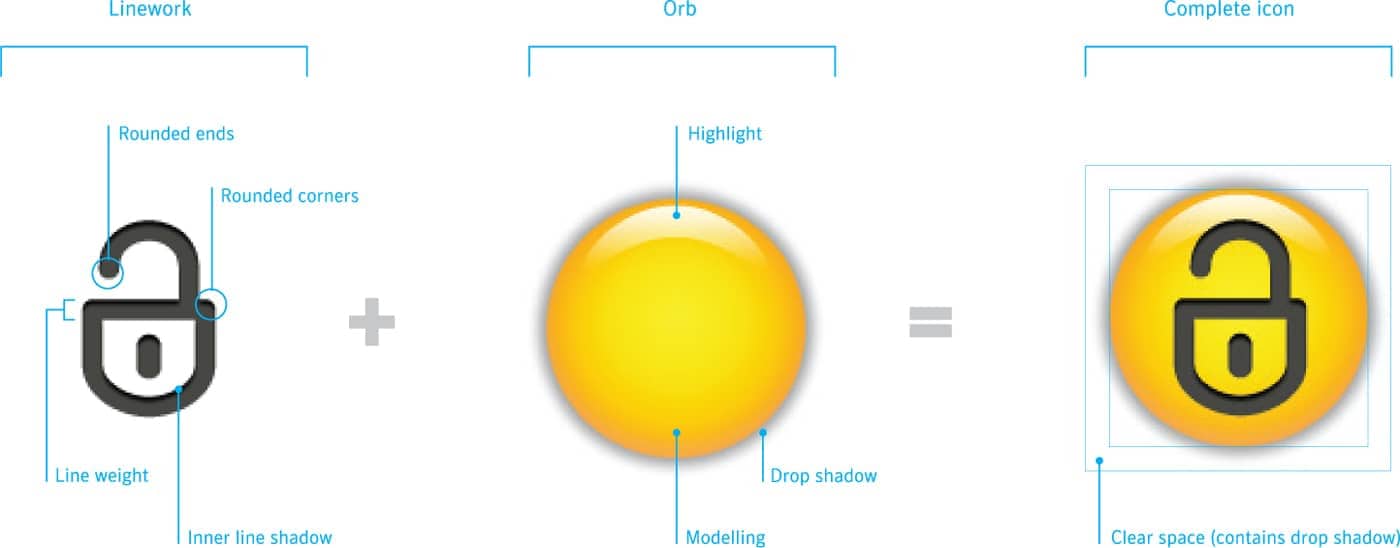

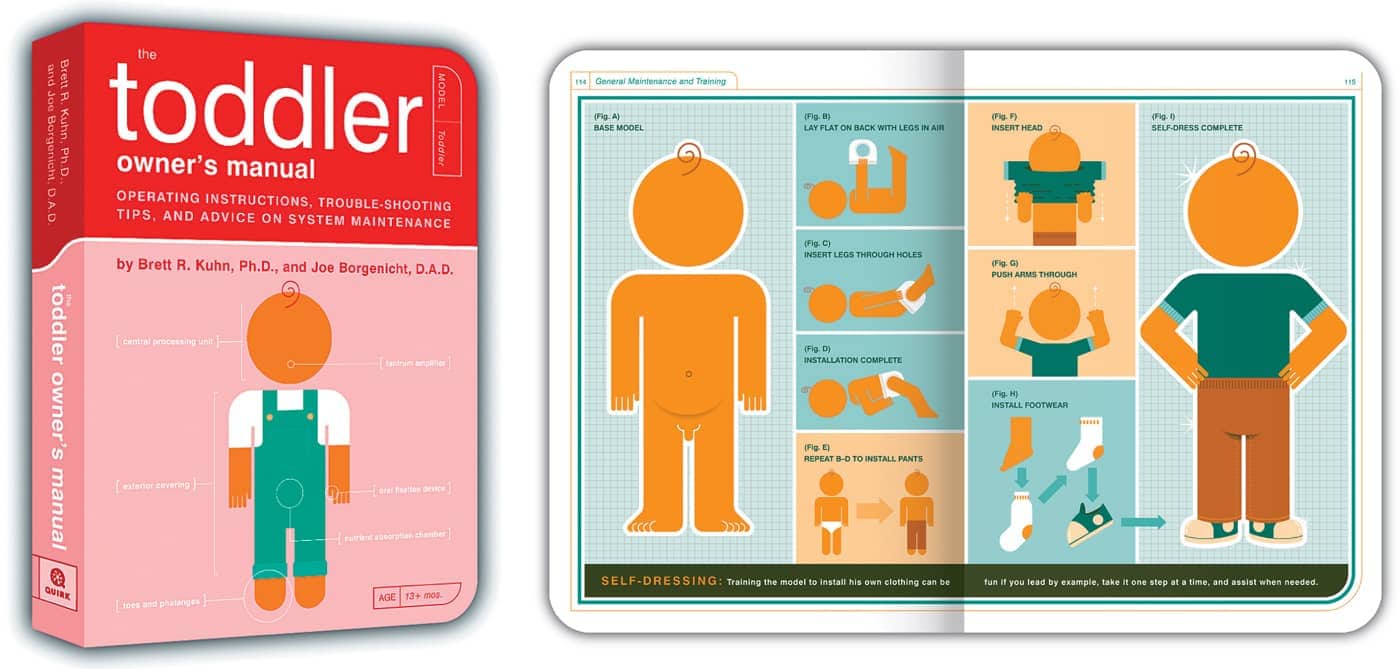

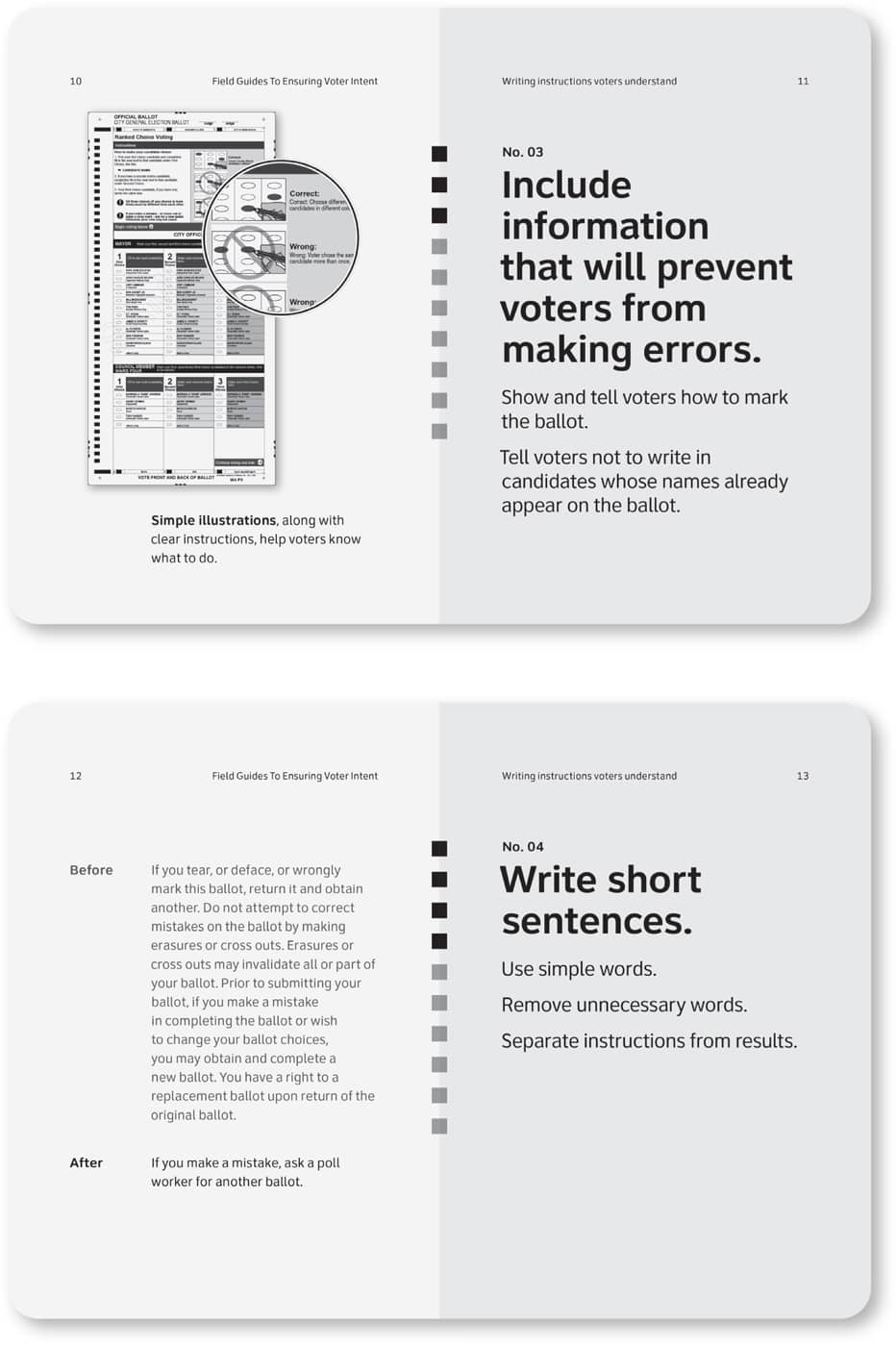

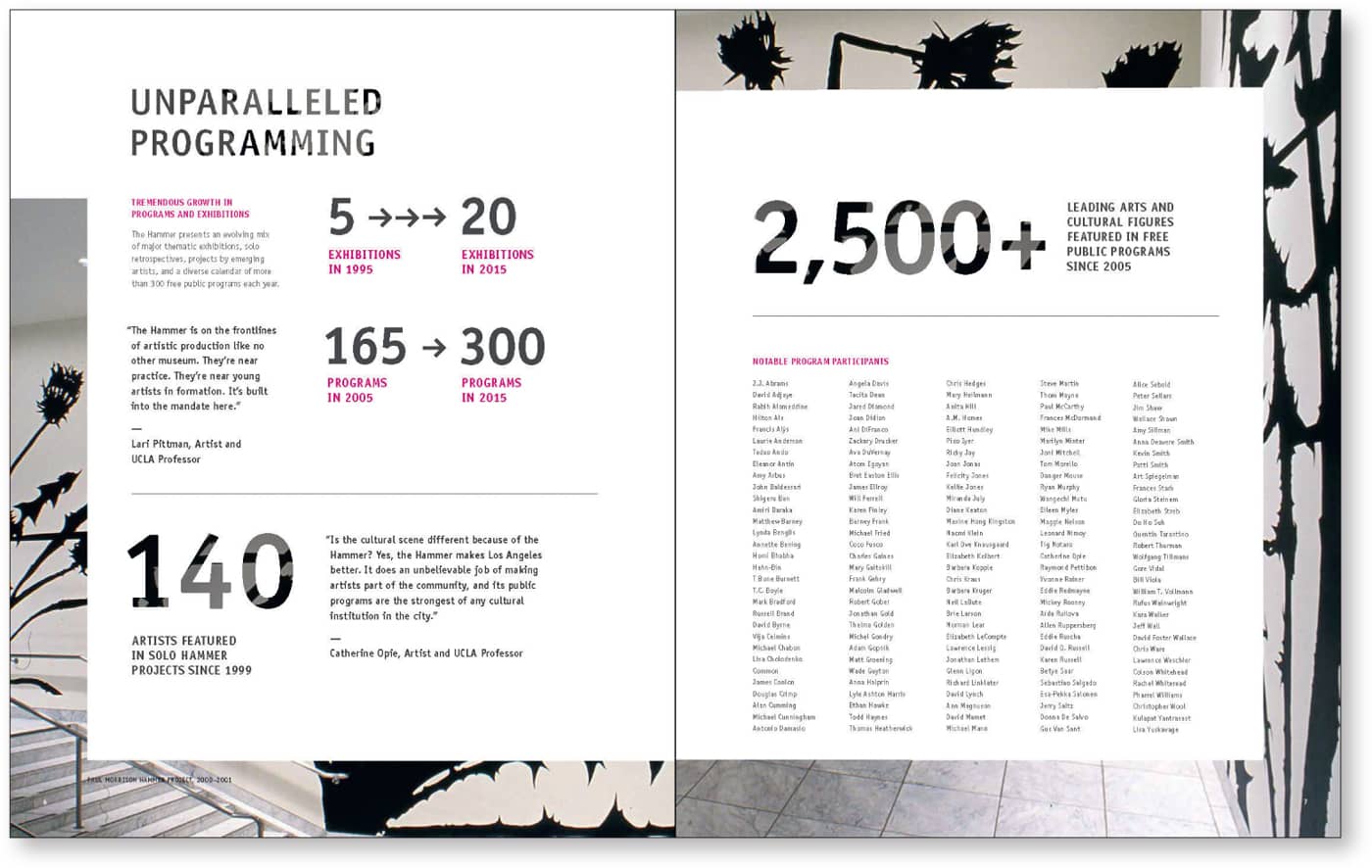

The creative brief is a short document (that’s why they call it a brief) that typically runs anywhere from two to 10 pages, depending on the scope of the project. This document outlines the pertinent information about the project so that the entire team has a clear sense of the project’s background and goals. Creative briefs are nothing new to the world of communication and design. These documents have been around forever in the advertising world. The same reason an agency would create a brief for a campaign applies to any design project: it’s important to have a good plan. Information design projects, in particular, tend toward the kind of complexity that makes having a thoughtfully crafted creative brief especially helpful. Too many projects proceed without the benefit of a clearly defined road map for the team. Without explicitly clear directions for how to move forward, information design project teams often find themselves either floundering or going full steam ahead (possibly in the wrong direction) while the clock ticks and budgets drain away. Good is a magazine that provides a platform for the ideas, people, and businesses that are driving change in the world. In a recurring section called “Transparency,” Good features a self-described “graphical exploration of the data that surrounds us.” Information graphics for each issue are created by different design firms, so Open, the firm responsible for the initial publication design, developed a creative brief to document and convey the most important aspects of the magazine’s mission and personality. Open Let’s say you’ve successfully set the stage for your project. You’ve spent time with the client and have a working understanding of their overall history and goals for their company and for the specific project at hand. Before you jump into the deep end and begin work on the project itself, it’s time to document what you’ve learned so far. There is apparently some debate in the design community (who knew?) over what makes for the perfect creative brief. There is debate over appropriate page count. Some people say, “It must be no longer than one page.” There is debate over the brief’s target audience. Some say, “The brief is the means by which you manage client expectations.” Many others believe that the perfect creative brief speaks directly to the creative team and its process. Our thinking is that the perfect creative brief is tailored to the project and the team who needs to use it. Many times, the members of your design team haven’t been in initial project meetings. They have no prior knowledge of the client or project. You could hold meetings, send emails, and verbally discuss what you know—all good. But what if you forget something or leave out critical bits of info? The creative brief acts as a single point of communication to ensure that everyone is on the same page as the project moves forward. In addition, the brief can spark creative juices and get them flowing. Informed by clearly defined project goals, the annual review for Forest Products Association of Canada makes excellent use of subheads, diagrams, and interesting custom photos that illustrate key concepts. McMillan Because of the creative brief, Smart Design knew that one challenge in designing packaging is that retailers often take products out of the box for floor display. Smart Design created a sophisticated approach with a label affixed to the product itself, identifying the product and giving potential buyers an overview of product benefits. (See case study on this page.) Smart Design Design Team Reference. Projects start and stop due to unforeseeable events. Team members come and go. People are often working on several projects simultaneously. Even if you wanted to memorize all key project info, who has the time or mental bandwidth? A creative brief can be a repository for the critical, practical, and inspirational information you know you’ll reference repeatedly. The brief is “the source” for project requirements and should be used as a benchmark to make sure the creative work is on target. Client Approval and Feedback. The client should give attention and final approval to the creative brief before any work begins, to guarantee that the project is off to a good start. The brief should echo the client’s key points that you heard during conversations with them. In responding to the brief, the client can help you correct the course, vet your ideas and assertions, and help you home in on what’s important to them. In addition, the client can use the brief to get critical internal buy-in or feedback and to gather input from people who, while not directly involved with the project, are never-the-less key players behind the scenes. Based on consultation with key stakeholders to assess needs, comprehensive guidelines allow in-house teams to implement a system of icons around the globe for a leading cyber security firm. MetaDesign For Some Eyes Only. Some creative briefs are more detailed than others, depending on the complexity of the job, communication challenges, and the needs of the team. The document truly can be whatever you need it to be. For example, there may be times where you decide to create a “special edition” or version of the creative brief for your internal design team. There may be details that you don’t want to highlight in the official brief that can really help your team understand the finer points of the project landscape. There may be client quirks, likes, dislikes, biases, past history, or even political agendas that would be useful to know as key design decisions are mapped out. An internal version of the creative brief can give your team the “inside scoop” about the client or project. Bottom line: there’s simply no right or wrong way to do it. What’s important is that the creative brief captures the critical information so that the people who need it are on the same page. Also critical: Get sign-off on the brief from your client to make sure your understanding of the project is accurate and complete. Client Peace of Mind. Once approved, the brief can help put the client’s mind at ease while the designers cloister themselves away and get down to the task of designing. As the creative process ensues over the course of several days or weeks, the client team knows there is a plan, has participated in the creation of that plan, and has a document that serves as a concrete reminder while they eagerly await the results of your genius. A typical creative brief breaks down information into four general categories: client information, project information, project goals and requirements, and project logistics. Client Information. Include the client’s full company name, number of years in business, noteworthy business accomplishments, whether it’s a regional or national organization, and so on. Client Sector. Give a bit of information about the client’s business or industry. How competitive is their marketplace? Has their industry gone through particular changes lately? Competitor Information. List your client’s top three to five competitors and give a brief overview of each competitor’s strengths and weaknesses in relation to your client. Intended Audiences. Who are the main audiences for this client? Is there a particular subset for the information design project? The Business Context for the Project. A thorough creative brief will take the following into account: Project Overview. Ideally, this is a one- or two-sentence overview of the project. Key Information and Hierarchy. It also helps to address these issues when writing an effective creative brief: The publisher of The Toddler Owner’s Manual: Operating Instructions, Trouble-Shooting Tips, and Advice on System Maintenance was looking for an alternative to the cutesy baby book. The designers implemented an owner’s manual aesthetic for the project. The book’s atypical look and feel appeal to a male audience, a goal stated in the initial creative brief. Headcase Design The Center for Civic Design thinks about democracy as a design problem. With skills in research, usability, design, accessibility, and plain language, the center’s goal is to improve the voting experience and make elections easier to administer. The center’s Field Guides provide user-friendly design guidelines for election officials in the United States that are based on solid research and best practices. The center provides all its toolkits and templates under the Creative Commons agreement for easy sharing and access. Oxide Design Co./Rule29 When Time magazine decided to reinvent itself, the design team drafted a creative brief with the following goal: Create a newsweekly that people would want to read. Bold photography and typography create a sense of gravitas and impact. Pentagram “There are an infinite number of journeys to take through the design of understanding.” —Richard Saul Wurman Specific List of Deliverables. State the deliverables, as you understand them (including page counts, document sizes, file types, and so on). Overview of the Project Team. Include key players on the client and design teams. Clearly define roles and responsibilities. Determine who signs off on deliverables. Key Dates. A detailed project schedule can be provided separately, but, by all means, list out the key dates you already know about. Budget/Hours. Include an overview of hours allocated to the project, ideally by project phase. Typically the person who’s had the most contact with the client during the project start-up phase writes the brief. This could be the project manager, the account manager, or even the creative director or designer. Ideally, whoever writes the brief should be: “Information design is still, to some degree, the prisoner of an old either/or paradigm in which words and images exist in completely separate domains.” —Robert E. Horn It’s worth the time you spend writing a creative brief. Done right, the approved document isn’t just created for posterity. It can ground your design decisions at every step along the way. When you’re ready to present to the client, reintroduce the brief to jog everyone’s memories. Explain your design decisions as they map to key points in the brief. This way, when the clients are responding to the work and making design choices, they’re doing so from a strategic point of view, as opposed to just a gut, or personal, response. The creative brief outlined the main goal for the Hammer Museum at UCLA’s fund-raising brochure: convey the critical need to evolve the museum’s programmatic and architectural vision. By focusing on key indicators of the institution’s thought leadership and using evocative photography of its art installations as visual texture throughout, this piece was an effective tool for the museum’s ambitious campaign. KBDAThe Creative Brief

WHAT IS A CREATIVE BRIEF?

WHY CREATE A CREATIVE BRIEF?

CREATIVE BRIEF CONTENT: A SOURDOUGH STARTER KIT

WHO NEEDS IT AND WHY?

TYPICAL CREATIVE BRIEF CONTENT

Project Information

Project Goals and Requirements

Project Logistics

WHO WRITES THE BRIEF?

THE CREATIVE BRIEF IN ACTION

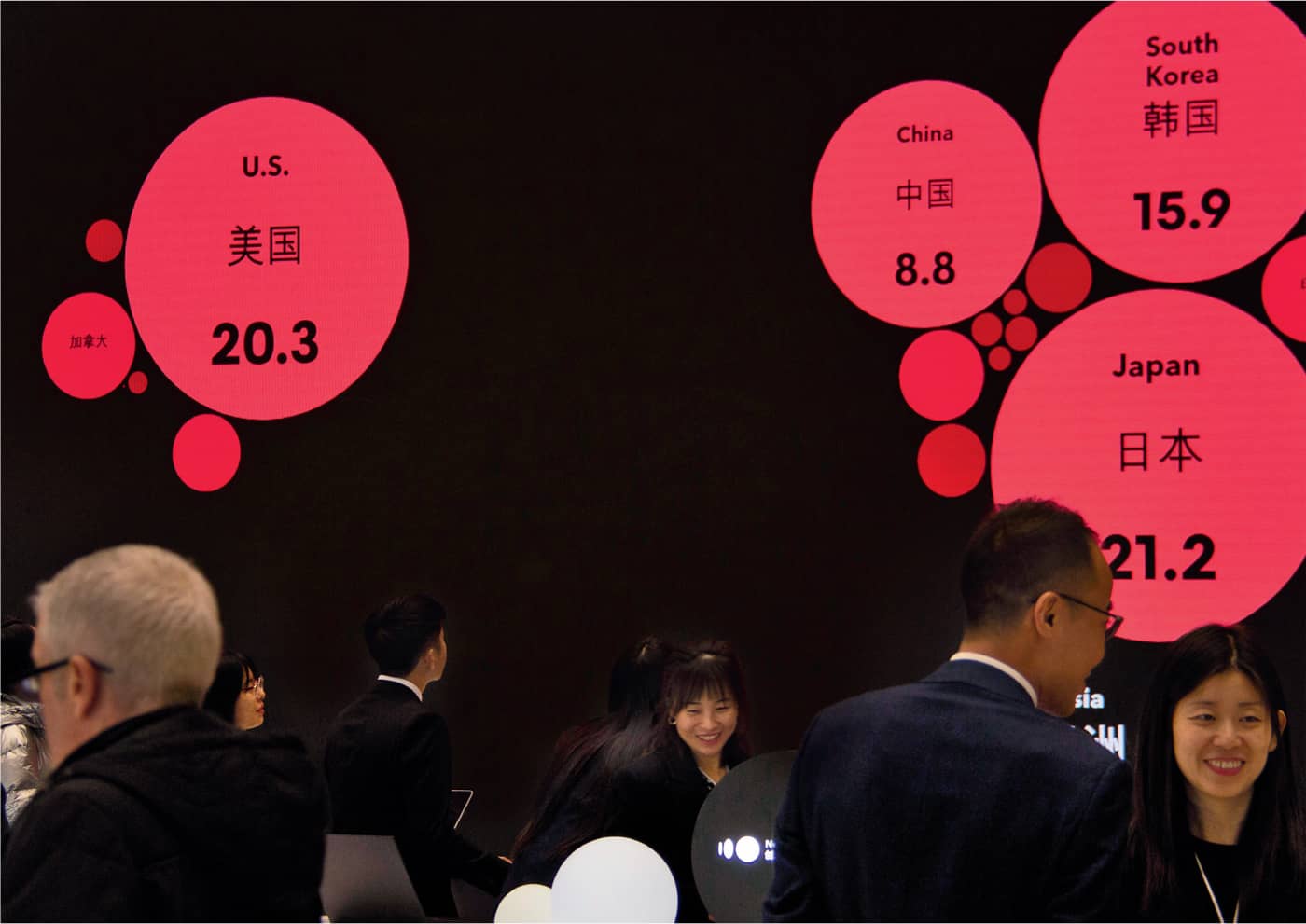

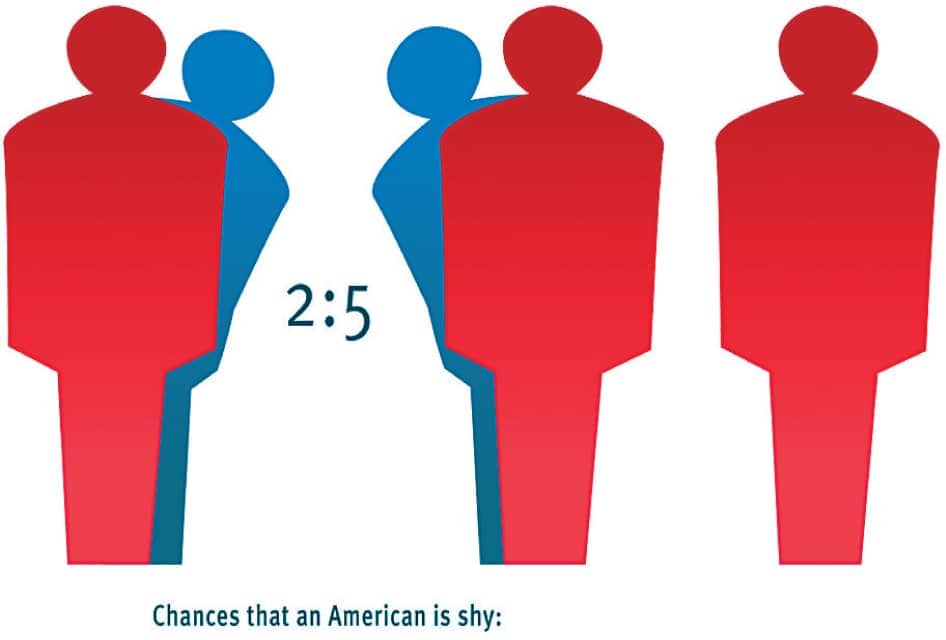

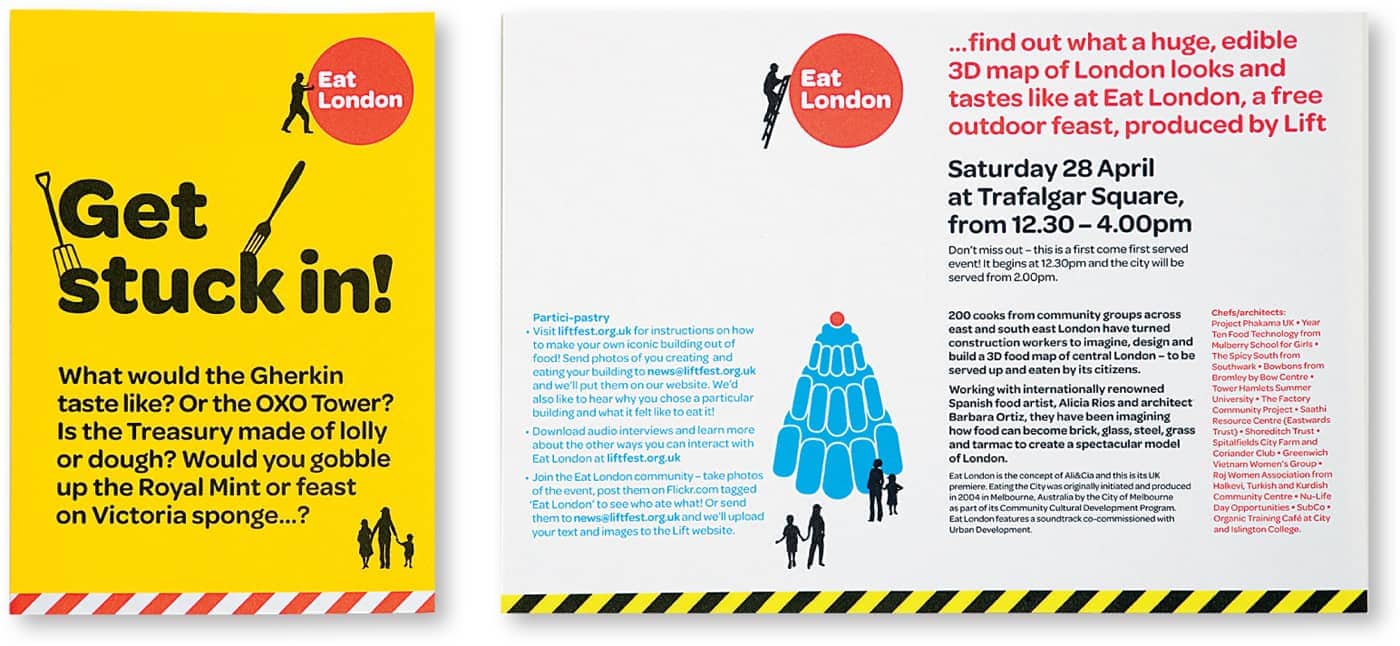

“Insight is what is created as we add context and give care to both the presentation and organization of data, as well as the particular needs of our audience.” —Nathan Shedroff What does the audience need to know and why do they need to know it? Emotional Requirements. How do you want your audience to respond emotionally to the information? Do you want to reassure them? Inspire them? Motivate them to do something? Physical Requirements. It’s critical to anticipate the physical context in which information will be reviewed. (See “Defining Audiences: User Profiles and Journeys,” for more information on how to map out useful details about audience needs and requirements.) How can information design address emotional aspects of information? This graphic depicts the percentage of Americans who claim they suffer from shyness. Sonia Chia A center at the USC Marshall School of Business wanted to produce an impactful mailer to increase brand awareness. The designer recommended a dramatic print format that unfolds to reveal an infographic showcasing key aspects of the program at a glance. The unconventional format reinforced the center’s reputation for innovation, while staying true to the university’s brand guidelines. When the foldout print piece was well received, the client asked the designer to translate the design so it could be effective for email distribution. The designer created a wireframe to show how the content would need to be formatted for the electronic edition. Pull quotes, captions, and timeline graphics were introduced into this report to provide multiple entry points to readers and to ensure that key messages surfaced. KBDA Frequent subheads, short text line lengths, and captioned before-and-after graphics made this report easy to scan for information. KBDA Chunks of information grouped by color in short paragraphs helped make this invitation for a large London culinary event easy and fun to read. thomas.matthews The world has changed dramatically over the last decade. Organizations must constantly redefine their markets and business models, while seeking higher rates of productivity. They must often accomplish these Herculean tasks with fewer internal resources and a leaner workforce. Long ago, clients approached designers with final content ready to be produced. In a business environment that is constantly evolving, today’s clients are often hard pressed to find the time and clarity to think through their communications issues, much less develop refined, on-target content. Guide the Content Creation Design. It’s safe to say that information design combines communication and content more directly and thoroughly than almost any other design discipline. Design and content processes continually inform each other. Today’s information designer may be faced with the unexpected challenge of having to help the client think through the content at several stages of the project. There are times when a client will deliver content and you’ll discover real challenges with the writing tone or the message. Other times the copy may only need simple refinements. Information Design as Advocacy. Even the most organized clients may need your help, or at the very least your “bird’s-eye view.” In addition to thinking through the design issues, you can be a key advocate for the end user. If you have a difficult time immediately grasping the content, chances are the reader will have a hard time too—especially since a typical reader will quickly turn away from information that is difficult to absorb. You’ll be most valuable to clients when you are simultaneously “half in” and “half out” of their organization so that you can offer informed, objective advice. There Could Be Gold in Those Mountains of Data. Whenever we start a new project, we like to hear the beep-beep-beeping sound of a large dump truck backing up to our office to unload mountains of data and documentation. The more you know about a client’s history, their business sector, and past projects, the better you can solve the design problem at hand. Content Strategy: See the Forest and the Trees. As you assist your client in thinking through the strategic development of content, we recommend you address the following: The rapid rise of information technologies means there is more data than ever to analyze. Dashboards have become an increasingly important tool to present critical information at a glance. To provide meaningful insights, these tools require a sophisticated approach to information design. Ash Arnett “Design, initially, is knowing how to ask the right questions.” —David Macaulay Tasked with engaging audiences of all ages with scientific material of varying complexity, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County’s exhibit design team developed a multilayered content approach for its Dinosaur Hall. Curiosity-piquing headlines and an approachable writing tone, expansive murals and supergraphics, and detailed annotations of information graphics encourage all visitors to connect with these compelling stories. KBDA The design of the onsite visitor orientation map at Descanso Gardens includes chalkboard-based modular panels to reflect frequent updates to program offerings and seasonal blooms. KBDA Review Content While in Development. Once the client provides you with the content, review it carefully: Conclusion: Master Content Wranglers Make Better Designers. Even though content wrangling may appear to be more work than you bargained for, in the end, several benefits emerge as a result of being involved in this part of the process. If you’re naturally curious and drawn to information design, you probably already have an affinity for content. Whether you’re a content junkie or an unsuspecting designer who’s been thrown into an information design quagmire, staying on top of the content development process helps you: Additional Firepower. Some designers can find themselves overwhelmed by the idea of being asked to help resolve content issues. If you and your team have written communication skills and bandwidth, you may be able to offer this as a billable service to your clients. Alternatively you can partner with skilled writers and copy editors who can become key allies in the process. Not every good copywriter is adept at thinking through the complex issues inherent in information design projects. If you do seek out partners, look for writers whose particular skill sets and experience match the project requirements. Planning for the Long Run. In the past, many design artifacts had an expected shelf life of several years, but now changing business and information needs means a shorter shelf life for many projects, and the need for frequent updates. For ever-evolving projects, such as websites, newsletters, or public information graphics, how will future updates be accomplished? It’s important to ascertain any content updating issues early in the project so you can make informed decisions about file formats and other logistics. Here are some good questions to ask about content updating: Schema, a Portland-based design firm, created 50 bold data visualizations displayed on two massive media walls to highlight conference topics at The Bloomberg New Economy Forum. A sophisticated back-end system let Bloomberg’s editorial team update the data visualizations dynamically, creating an easy workflow and a compelling experience for attendees. Schema/Bloomberg Is It Bigger Than a Breadbox? “Form factor” is a term used in computing and engineering to describe size, format, shape, packaging, or housing of devices and mechanisms. We find ourselves appropriating the term to refer to design projects as well. There are plenty of considerations to take into account when deciding on the final “form factor” for an information design piece. “There is no such thing as objectivity. Even acts as simple and seemingly innocent as organizing data are subjective. Indeed, organizing data and the creating of information may have a profound impact on its meaning.” —Nathan ShedroffWrangling Content

UNDERSTAND THE REQUIREMENTS

BLOSS

BLOSS

CONTENT CAN BE A MOVING TARGET

CONTENT ANALYSIS