Who is the ‘virtual’ you and do you know who’s watching you?

Abstract

Navigating the minefield that comprises the privacy settings for the majority of social networking websites is at best a frustrating experience which leaves the user with the vague feeling that although they’ve left the house, the gas oven is still turned on. At worst, the host vendor of the social networking website deliberately prevents the user from modifying the privacy settings in such a way that the user’s privacy is genuinely protected. In all cases, the verbiage spelling out the user’s privacy rights as supported by a given site tends to be so convoluted that even the most hardened lawyer would have difficulty teasing the sense out of it. The consequences of engaging in social networking without taking precautions can be severe, ranging from identity theft to being stalked online and abuse of personal information by a third party. Because user privacy is not in the best interests of the social networking vendors, it’s up to users to look out for their own privacy and to set up safeguards that protect their social data, their identity and, ultimately, their ‘virtual self’.

‘Stay, quoth Reputation/Do not forsake me; for it is my nature/If once I part from any man I meet/I am never found again.’

(Webster, 2000, line 156)

Awareness of data privacy, digital footprints, maintaining separate work and personal online identities, and other types of identity concerns

Researchers from the Pew Internet & American Life Project have found that the number of Americans using ‘social networking sites (SNSs) in 2011 has nearly doubled from the number of SNS users in 2008’ (Hampton et al., 2011, para. 3). The Pew Internet & American Life Project also notes that users of social networking websites are becoming more aware of the identity and privacy issues associated with social networking.

When considering issues of identity, personal data and privacy, it’s important to avoid using the terms interchangeably because the effectiveness of the various approaches to safeguarding each category depends on the type of data being safeguarded. Another element that has to be taken into consideration is the relative sensitivity of data when it can be connected with other chunks of data and placed into a particular context. While the numbers ‘100954’ mean very little standing on their own, if you connect the numbers with the context of ‘birthday’ they then acquire meaning.

What is an online identity?

So what exactly do we mean when we say ‘identity’ or ‘personal data?’ Castells (2009) makes a number of interesting points concerning cultural and collective identity, stating that ‘[i]dentity is people’s source of meaning and experience’ (p. 6). This statement implies that identity is something that people derive from some external agency, such as their local culture, events that they’ve experienced, or some other collection of cultural attributes that define who they are.

In the most tightly defined sense, it could be said that an online identity is that collection of individually descriptive data that is contained within a person’s online profile. Feizy et al. (2010) use this definition exclusively: ‘In online social networking sites, people define an identity through the definition of information within a profile’ (p. 1). Particularly when signing up for social networking membership with any of the vendors, the user is strongly encouraged by the website to include a wide variety of identity-related data, such as the user’s birth date, address, contact information, preferences, and so on.

The implications are noted by Neal and Williams (2009): ‘as in the Aristotelian saying, “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts”, the aggregated whole may represent a body of personal data that [implies] ownership, such that the user would have defensible rights over the aggregation, if not the disaggregated pieces’ (p. 4). Further, users have little control over how personal data residing with a variety of entities can be linked together to create their online identity. Neal and Williams (2010) observe that, in the US, current privacy legislation essentially allows SNSs to aggregate and link the data residing on their servers in any fashion that they wish. Users of US-based SNSs who physically reside outside the US are at equal risk of having their personal data linked or exposed in unintended ways.

Taking our search for a definition a step further, we already know that the context of data can transform that data from a meaningless set of characters into meaningful information. Context is an element that can’t be easily controlled by the individual and provides a useful method for drawing a true picture of that individual’s online identity (Madden et al., 2007).

Even when an organization actively employs one or more ‘depersonalization’ techniques on stored personal data, none of them can guarantee to safeguard the more sensitive data in 100 per cent of all cases. Given the business model on which the majority of SNSs are based, depersonalization is actually a disadvantage to the SNS hosts. It’s difficult to market purple people-eating zinnia clippers to your users if you can’t clearly identify those customers who have expressed a rampant interest in purple people-eating zinnia clippers!

What is privacy?

As with identity, for the purposes of our discussion here, we need to look at privacy through the lens of an online environment. Gavison (2011) remarks that many current legal definitions of privacy are the subject of much debate. In most definitions, privacy includes a ‘“right to be left alone”, covering a general interest in not being interfered with in any way that violates human dignity’ (pp. 400–1).

Williams and Neal (2009) note that, with the advent of more powerful data mining techniques, the aggregation of seemingly innocuous personal data across a range of social media makes it fairly straightforward to put together a disturbingly detailed profile of the data’s originator. Although the originator may have been careful when giving information to the individual websites, the ability to aggregate data belonging to that originator across a variety of sites creates an unintended consequence. Because the originator has no way of knowing when this kind of data aggregation will occur, or who the gathering entity may be, it’s impossible to safeguard your personal data against being aggregated. The only viable option is simply to not participate in social networking, although that approach will still leave any data residing in organizational online databases available and vulnerable in many cases.

Another element that muddies the privacy waters is the fact that total privacy, that is, an absolute limitation on what can be known about a person, is undesirable and could be potentially harmful. Consider the case of a convicted sex offender; while it can be assumed that the offender would desire to keep his or her criminal history entirely private, the community in which the offender resides would almost certainly disagree.

What is a digital footprint?

Weaver and Gahegan (2007) define a digital footprint as ‘a high dimensional and constantly growing space characterized by digital transactions, augmented by surveillance, and influenced by associations and patterns through space and time’ (p. 330). What on earth does that mean?

This definition encompasses almost everything that the average American does on an average day. Let’s follow Joe Average as he goes about what he thinks is his own business. When Joe awakens in the morning, he rolls out of bed and has a shower. While drying off, he turns on the television to watch some news. His set-top cable box keeps track of every channel to which he surfs and reports his viewing habits back to his cable company. Whether he knows it or not, the set-top box also keeps track of what his digital programme recorder records and reports that information back as well, including the Debbie Does Fort Worth adult movie he watched last night. While having his coffee, he checks his email on his mobile phone, which is tracking both his location and his habits. An application that he downloaded to his phone a couple of months ago for receiving tips on nearby restaurants continually updates where his phone is and sends that information back to the application’s developers.

When he arrives at work, he searches his favourites and opens a news website to catch up on the national news. The website keeps track of all of the links that Joe clicks as he reads various articles, and logs his interests. The EULA (end user licence agreement) that Joe signed when he signed up for the website allows the site to not only keep track of his news reading habits but also to sell that information to third parties, such as marketers, which is how the news site makes most of its revenue. The news site isn’t the only entity tracking Joe’s viewing habits. His employer uses monitoring software to keep track of what employees are doing with their company computers. The company maintains a fair use policy that allows employees some leeway for checking their personal email or doing some online shopping in their lunch hour. If an employee spends more than their fair use allowance on personal web surfing they receive a warning which goes into their employee records.

On his way home after work, Joe calls his brother on his mobile phone. His phone company logs the minutes he’s using, the number he has dialled and also records the location of the phone. After supper, Joe pays some of his bills online. Each transaction is logged on the various websites for his phone company, his utility company and his bank. Joe watches a little television after he has paid his bills, still being tracked by his set-top box and finally goes to bed, which is practically the only action he has taken all day that hasn’t been recorded, logged and stored in a database somewhere.

This just describes a single day in the life of a digital footprint. Every day, companies collect data about all of us, our television viewing habits, our banking and credit profile, even the route we take to drive to work, grow larger at an exponential rate. Gantz and Reinsel (2011) estimated that the amount of personal data stored online would top 1.8 trillion gigabytes by the end of 2011. They went on to note that while 75 per cent of the data stored online is generated by or about individuals, the liability for around 80 per cent of that data falls on commercial entities. ‘Less than a third of the information in the digital universe can be said to have at least minimal security or protection; only about half the information that should be protected is protected’ (p. 1). The majority of those entities who actively seek to acquire and store personal information have based their business focus on the value of something called ‘big data’. Big data isn’t a thing so much as a phenomenon. It’s the result of increasingly less expensive storage technologies that are also capable of storing ever greater quantities of data. The data in and of itself doesn’t have much value to anyone aside from the person to whom the data refers. But when you add context, such as not just the person’s location, but what the person was doing at that location, then you begin to obtain value. Big data is all about extracting as much commercial value from this rapidly expanding storehouse of personal data as can be managed without actively running afoul of any pesky privacy laws. Your digital footprint spells profit for these commercial entities and it is not in their best interests to protect your privacy.

Maintaining separate personal and professional online identities

Very few of us are exactly the same person 100 per cent of the time. With our parents, we’re their children; at work, we’re colleagues; and in our leisure time, we’re yet another person with our friends. The divide between our personal and professional identities is probably the deepest out of the range of identities that we wear on a daily basis. Rozuel (2011) refers to this internal separation of identities as ‘compartmentalization’, where we each place bits and pieces of our work selves in one main box, and other bits and pieces into our personal selves’ box.

The online blurring of roles is becoming steadily more common as commercial entities deliberately attempt to convince users to weave every aspect of their lives, both public and private, together into a single amalgamated alloy of roles. A good current example of the increased overlap between online personal and public identities is a new social networking initiative deployed by Google called Google +. Google + includes much of the same interactivity that Facebook does, with some twists. Since Google’s primary business is searching and organizing data, it intends to make all of the social networking data within Google + publicly searchable. From the Google privacy policy: ‘We may combine the information you submit under your account with information from other Google services or third parties in order to provide you with a better experience and to improve the quality of our services’ (Google, 2011, para. 3). If you have more than one Gmail account (or multiple Google Calendars, Google Docs, etc.), all of your data – regardless of whatever separate accounts you’ve used – will be lumped together to make it easier for Google and any third parties of their choosing to target your interests and habits.

Arguments about finding a balance between work and personal lives aside, is it wise to combine the work role with the personal role, so far as information is concerned? The answer to this question almost certainly depends upon a person’s own feelings about the work–personal space separation. Perhaps an individual simply doesn’t feel that it’s any of their work colleagues’ business knowing that they design doll house furniture as a hobby or that they enjoy geocaching. On the other hand, particularly if a person is self-employed, it may be perfectly acceptable to combine both business and personal roles without a problem. Generally speaking though, the majority of us do seem to prefer at least a modicum of separation between work and personal life. For example, a teacher may prefer to maintain a certain amount of professional distance between herself and her students.

The monetization of personal information has ramped up the pressure on individuals to blur and combine their personal information, which makes it easier for commercial entities to build up and optimize an individual’s ‘big data’ profile. An example of this type of pressure is Facebook’s ‘Connections’ feature. Essentially, anything in a Facebook profile, such as friends, family, interests, religious views and anything else used to personalize the account, can be searched by any third-party entity, whether or not they’re directly affiliated with Facebook. Rather disingenuously, although Facebook states that this information isn’t ‘visible’ to anyone other than those who the user has explicitly allowed to view the information, visibility has nothing to do with the ‘searchability’ of the information. Facebook’s privacy policy also leaves the door open to new avenues of searchability: ‘Facebook does not give third party applications or ad networks the right to use your name or picture in ads. If we allow this in the future, the setting you choose will determine how your information is used’ (Facebook, 2011, para. 1; italic added by author). If and when public third parties are allowed to search all of your Facebook information, regardless of how many separate Facebook accounts you may maintain, those compartmentalized bits of your life will be blended regardless of your own preferences.

Many of the previous concerns are founded on the ability of various types of software to make textual connections. However, searching and making connections between all sorts of information is about to get much more interesting as Google has apparently figured out how to semantically search images: http://images.google.com. If this rumour (in early 2012) proves to be true, it will greatly enhance (for better or worse) the ability of Google’s image similarity algorithm to match up online images of yourself with personal information. The key here is the concept of a semantic search. A semantic search not only looks for keywords but is also capable of interpreting the meaning behind the words used for the search terms. Thus, if you misspent at least part of your youth and then decided to share the digital snapshots with your friends on the SNS of your choice, there’s a strong possibility that any images you uploaded from spring break on the beach in Puerto Vallarta can now be linked to your professional profile photo on LinkedIn. If this same search is semantically enhanced, the chances of linking your images with your personal information become considerably greater. Google isn’t the only game in town when it comes to semantic image searching; TinEye© and Picsearch© are also working on their own proprietary image searching methods. With employers increasingly using web searches to get a look at the private life of potential employees, the ability to connect images with not only context but meaning as well could dramatically change the job search process.

Data privacy and the ‘virtual’ you

With all of these corrosive threats against your personal data, what should concern you in particular as an educator? Are there areas within the overall personal data debate that may be especially sensitive within an education setting?

In many ways, these questions will lead us to new wine in old bottles, that is to say that social networking and the availability of increasing amounts of personal data only exacerbate the same ethical dilemmas that educators have always had to face. For instance, if you keep a personal Facebook page and a student sends you a ‘friend request’, should you accept? Should you be concerned if students find and read your personal Facebook page? Is there a significant difference between the information on your Facebook page and your LinkedIn page? None of this really differs from traditional concerns, such as forming inappropriate friendships with students or having students discover personal information about you that you might have preferred to keep personal.

Where online ethical dilemmas differ from traditional ethical dilemmas is both in the potential lifetime of the data as well the availability of the data. Once your data goes online it will potentially persist online in some form for an indefinite period of time, certainly for years. Even if you go back to the site where you originally uploaded the data and delete everything, copies of the data will remain tucked away in various places, such as the site’s backup files, Archive.org or third-party entities that have used the information for marketing purposes.

Dealing with students disgruntled over a low grade or a disciplinary incident acquires a significantly higher risk of retaliation when the educator engages in social networking. Hacking most user accounts on Facebook is a relatively simple exercise; once inside your account the hacker can easily change your profile information and friends list. Rusli (2010) describes the ease with which your Facebook profile can be hijacked. Debatin et al. (2009) then provide an eye-opening example of what can happen after the hacker has got in:

The first time [that Brian’s Facebook account was hacked], the hacker changed some of Brian’s groups and altered his “interested in” selection to insinuate (incorrectly) that Brian was gay. He brushed the incident off as a joke, changed his password, and “went on with everyday life.” At that time, he was not aware of privacy options. Then, the hacker again entered his profile, changed his password back, and altered some things. Brian changed them back again and wrote on his status, “ok, you know, enough is enough … the joke’s over, this isn’t funny anymore.” On the third day, his profile was completely changed, including groups and interests, and his profile picture showed a combination of his head and a porn star’s body. The hacker had also put in a relationship request with Brian’s freshman-year roommate and changed his status to “I was just kidding. I’m having a hard time coming out of the closet right now.” To Brian’s dismay, all these changes were made public through the news feed.

There are also a number of privacy and security issues related to collaborative work with colleagues. A variety of sites, such as Office Live, offer collaborative tools that make it simple to maintain a single master copy of a research document, while at the same time allowing a group of researchers to edit and modify the document. Google Docs is a popular example of this type of collaborative tool, but as with other forms of social networking there are risks that accompany the benefits.

Barkah (2009) details three risk scenarios inherent in the use of Google Docs. His first scenario involves the difference between security settings between the master document and any images embedded within that document. When you upload an image that accompanies your text document, Google will assign that image a URL that points to the image’s location on the Google server. Inserting the image into your Google Doc requires that the document uses the image’s URL in order to locate it. Here’s the trick: because the document and the image exist on Google’s servers as two separate items, the security settings for each of them can (and usually do) differ. So, although you may have tightened up who can share and manipulate your text document, your image file is freely available to anyone who finds it. Obviously, if your research encompasses ideas that could be patentable this is a major concern as any figures embedded in a Google Doc can easily be copied and used by any stranger surfing by. Even if you delete the text document that contains the embedded images, they still linger on because they reside on the server as a separate entity.

Should you become sufficiently paranoid about the possibility of image snitching and lock down your sharing permissions, you still probably haven’t managed to close the barn door. Under certain circumstances, anyone to whom you’ve ever granted sharing permissions can still access the previously shared document even if you’ve removed them from your group of approved collaborators.

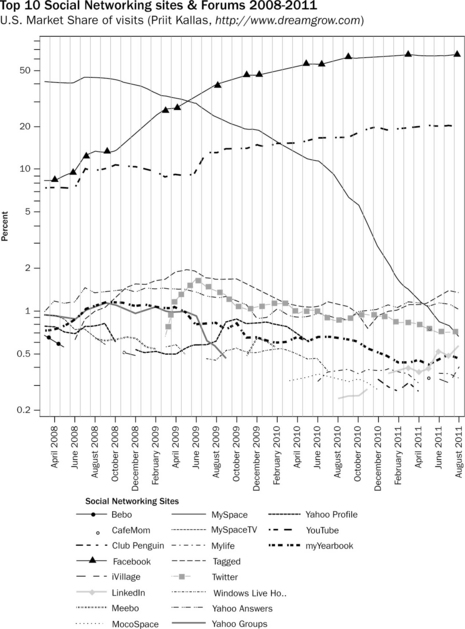

So, what are some safe options for engaging in social networking? If you’ve already been active on a variety of SNSs for several years you should probably begin to take some time about once a month or so to do some damage control. Facebook, Twitter and other forms of social networking all allow for a certain amount of privacy tweaking. Let’s take a look at the top three SNSs according to their August 2011 market share (see Figure 10.1).

10.1 Top ten social networking sites by market share, August 2011 Created by Pritt Kallas @ http://www.dreamgrow.com Data from http://www.marketingcharts.com/categories/social-networks-and-forums/ Note that the Hitwise data featured is based on US market share of visits as defined by the lAB, which is the percentage of online traffic to the domain or category, from the Hitwise sample of 10 million US Internet users. The market share of visits percentage does not include traffic for all sub-domains of certain websites that could be reported on separately.

Facebook is currently the 800 pound gorilla, with YouTube and Twitter bringing up the rear. YouTube was not purpose-built as an SNS, having simply evolved through its use of communities and subscriptions into a sort of visual social network. LinkedIn, although not in the top three at the time of writing, is closer to Facebook in format than YouTube.

Keeping in mind that many, if not all, of the following ‘best practice’ directives may change in the future, you can still get a general idea of what to look for when seeking to better manage your privacy settings as you engage with various SNSs.

Facebook privacy best practices

![]() Look at the bottom of any Facebook page. You should spot the privacy link; this will give you information concerning Facebook’s most current set of privacy policies. If you don’t quite understand how a given policy will affect how others view your profile, use the profile preview to double check. Try to remember to check the privacy policies about once a month (Sophos, 2011).

Look at the bottom of any Facebook page. You should spot the privacy link; this will give you information concerning Facebook’s most current set of privacy policies. If you don’t quite understand how a given policy will affect how others view your profile, use the profile preview to double check. Try to remember to check the privacy policies about once a month (Sophos, 2011).

![]() Be very choosy about who you accept as a friend. Keep in mind that anyone designated as a friend can access a lot of your information, depending on your settings (ibid.).

Be very choosy about who you accept as a friend. Keep in mind that anyone designated as a friend can access a lot of your information, depending on your settings (ibid.).

![]() Turn off all options that you don’t routinely use (ibid.).

Turn off all options that you don’t routinely use (ibid.).

![]() In your account settings, don’t provide a nickname that could easily link your account to other accounts you own. Don’t include personally identifying information in your nickname, such as your date of birth (ibid.).

In your account settings, don’t provide a nickname that could easily link your account to other accounts you own. Don’t include personally identifying information in your nickname, such as your date of birth (ibid.).

![]() In your account settings, reduce the permissions given to Facebook advertisements; the more that third parties know about your ‘likes’, the more you leave yourself open to social engineering attacks as well as marketing spam (ibid.).

In your account settings, reduce the permissions given to Facebook advertisements; the more that third parties know about your ‘likes’, the more you leave yourself open to social engineering attacks as well as marketing spam (ibid.).

![]() Facebook applications are probably the greatest single risk to your personal data because there’s no reliable way of knowing whether the developer is trustworthy or how the developer will use the information to which you give them access. Limit the number of applications that you allow to the bare minimum of what you actually use. Also limit or completely disable information accessible to your friends (ibid.).

Facebook applications are probably the greatest single risk to your personal data because there’s no reliable way of knowing whether the developer is trustworthy or how the developer will use the information to which you give them access. Limit the number of applications that you allow to the bare minimum of what you actually use. Also limit or completely disable information accessible to your friends (ibid.).

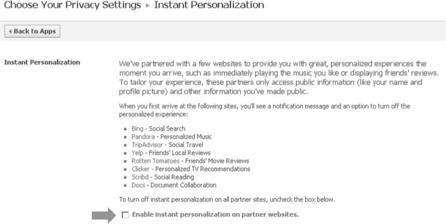

![]() Turn off ‘Instant personalization’. Click the down arrow to the right of the home link in the upper right-hand corner of your Facebook page. Click on ‘Privacy settings’. Click on ‘Edit settings’ in the ‘Applications and websites’ section. Click on ‘Edit setting’ in the ‘Instant personalization’ section then deselect the ‘Instant personalization’ box.

Turn off ‘Instant personalization’. Click the down arrow to the right of the home link in the upper right-hand corner of your Facebook page. Click on ‘Privacy settings’. Click on ‘Edit settings’ in the ‘Applications and websites’ section. Click on ‘Edit setting’ in the ‘Instant personalization’ section then deselect the ‘Instant personalization’ box.

![]() Also in ‘Applications and websites’, turn off ‘Public search’.

Also in ‘Applications and websites’, turn off ‘Public search’.

![]() Stay offline in Facebook Chat; Chat gives away your online status and can be used to scam you using hijacked credentials from a friend’s account (ibid.).

Stay offline in Facebook Chat; Chat gives away your online status and can be used to scam you using hijacked credentials from a friend’s account (ibid.).

![]() Customize your privacy settings. Keep in mind that even if you have every setting locked down to ‘Friends only’, there’s a growing possibility that some of your friends haven’t been as careful as you have and have had their accounts hacked, in which case the hacker can then access your information (ibid.).

Customize your privacy settings. Keep in mind that even if you have every setting locked down to ‘Friends only’, there’s a growing possibility that some of your friends haven’t been as careful as you have and have had their accounts hacked, in which case the hacker can then access your information (ibid.).

LinkedIn privacy best practices

All of the best practices noted in the Facebook section above also apply to LinkedIn. Interestingly, you seldom hear the same privacy horror stories about LinkedIn, which is probably due to the site’s emphasis on workplace connections rather than purely social links (Anna, 2011). Even though most LinkedIn users are on their best behaviour you still need to be careful about what you’re sharing and who you’re sharing it with. By now, just about everyone knows that they aren’t supposed to click on unsolicited attachments, with the emphasis on ‘unsolicited’. But what about email that appears to come from a friend? Would you automatically open an attachment that you received from a colleague, even though it doesn’t appear to relate to any current dialogue?

Many, if not most, people would, despite years of cautionary tales, simply because humans are hard-wired to trust people they know. Making your contact information too widely available on LinkedIn can make you more vulnerable to this type of social engineering attack, so share your contact information sparingly.

Twitter privacy best practices

![]() Remove as much of your personal information from your Twitter account as you can get away with. You want to avoid providing unknown followers with enough information to link up your Twitter account with any other SNSs that you may be using (O’Donnell, 2011).

Remove as much of your personal information from your Twitter account as you can get away with. You want to avoid providing unknown followers with enough information to link up your Twitter account with any other SNSs that you may be using (O’Donnell, 2011).

![]() Turn off your ‘Tweet location’. It’s never a good idea to let too many people know when you’re not at home. Remember that it’s easier to pick up followers on Twitter than it is to make friends on Facebook. Don’t provide complete strangers with your location (ibid.).

Turn off your ‘Tweet location’. It’s never a good idea to let too many people know when you’re not at home. Remember that it’s easier to pick up followers on Twitter than it is to make friends on Facebook. Don’t provide complete strangers with your location (ibid.).

![]() Turn on the ‘Protect my tweets’ feature. It won’t protect you from any followers that you’ve already picked up but it will allow you to approve (or not) any new followers that appear. Get rid of any unknown followers you already have by clicking on the gear icon next to the follower’s alias and selecting ‘Remove’ (ibid.).

Turn on the ‘Protect my tweets’ feature. It won’t protect you from any followers that you’ve already picked up but it will allow you to approve (or not) any new followers that appear. Get rid of any unknown followers you already have by clicking on the gear icon next to the follower’s alias and selecting ‘Remove’ (ibid.).

![]() Review all of the previously stated best practices for Facebook and LinkedIn!

Review all of the previously stated best practices for Facebook and LinkedIn!

Tracking your digital footprints

There are two distinct sides to the digital footprint discussion: those who actively use their digital footprint as a self-marketing tool and those who are concerned about their privacy. In either case, if you use the Internet regularly, and especially if you spend much time on SNSs, it’s a good idea to know not only the general size of your digital footprint but the breadth of it as well. Whether you like it or not, your digital footprint is the 21st century equivalent of your reputation and it will provide others with a picture of you that may be less than flattering.

An easy first step to measuring your digital footprint is to do a Google search on yourself. Be sure to use different combinations of your name to make sure that you dig up as much information as you can. The Innovative Educator (2011) also recommends some additional tools for measuring your digital footprint. Google Alerts (http://www.google.com/alerts) will allow you to monitor your own Google results. Should anyone post any information about you online that can be searched, Google Alerts will email you with the results. You can do a visual search using Spezify (http://spezify.com/); the results are placed in a type of connected table to give you an idea of which result is connected to other results and can give you an interesting look at how your digital footprint pieces are interlinked.

Keeping your work ‘you’ and your personal ‘you’ apart

There are plenty of people who have no desire to separate their private and public lives. If you are an entrepreneur it’s possible that you actually use social networks as an important marketing tool and wish to leverage your virtual influence as much as you can. However, many of us want to retain our compartmentalization and, as educators, would like to keep a respectful distance between ourselves and our students. Amber Mac (2011) provides some useful tips in this regard.

First, and easiest, is to use completely different SNSs for each compartment of your life, perhaps using Facebook for your personal networking, while restricting work-related networking to LinkedIn. You’ll need to hold firm on the people with whom you’re connected on each site; it won’t do you much good to try to maintain separate networking personas if you allow people from LinkedIn to become friends of yours on Facebook.

If Facebook is your SNS of choice you can still maintain a certain degree of separation by creating separate accounts for your personal and professional selves. Facebook allows users to create company pages that are set up explicitly for marketing purposes. By clicking on the ‘Pages’ link you can set up a business page for a business, company, public figure, brand, or community cause. To maintain separation, you’ll need to remember not to blend your personal friends with your professional fans.

In addition to creating a business page on Facebook, you might also consider moving your business contacts over to Twitter. While Twitter lacks many of the networking tools included with Facebook and LinkedIn it’s still useful for keeping clients and colleagues updated on your current activities.

Depending on Facebook’s privacy policy at any given time, you can also place various friends into particular groups, then restrict or allow access to your information based on the group. Use the ‘Privacy settings’ link to dig into the various pathways through which your data is shared to create different groups of people with varying degrees of permission. You can also place people into lists, based on whatever they have in common, such as real-life friends, family or professional contacts. Select your account drop-down menu, then select ‘Edit friends’; on the left sidebar, select ‘Lists’ and ‘Create a new list’. Depending on into which list you’ve placed a person, they’ll be able to view only the content that you allow for that list. Keep in mind that, on Facebook, visibility does not preclude searchability and if an individual on a restricted list is really determined to see some of the information to which they don’t have access there are still avenues that allow searching and possible discovery.

Probably the most effective way to maintain truly separate public and personal personas is simply to take yourself offline altogether. If that sounds too extreme, then just remember never to upload anything to an SNS that you wouldn’t feel comfortable seeing on a billboard by the side of a busy road.

If you do decide to take your online self offline, every SNS has the option to delete your account. For example, to delete your Facebook account, go to https://ssl.facebook.com/help/contact.php?show_form=delete_account, and follow the steps. Once you’ve reached the final step, it’s important that you do nothing else and simply close the page. It takes two weeks for Facebook to actually remove your account, so if you log back on at any time before the two week deadline is up your account is automatically reinstated. If you use Facebook Connect to log into sites other than Facebook itself, using Connect to log in will also automatically reinstate your account.

What should you know in order to adequately protect all of your ‘you’s?

Over the past decade, a number of businesses have sprung up that claim to safeguard your overall identity for a fee, such as LifeLock and IdentityGuard. In general, companies like LifeLock do little to help protect your social networking activities, being more concerned with guarding your credit score and preventing illegal use of your financial information. While identity protection companies do provide a certain degree of convenience, they really don’t do anything that you can’t do yourself.

For those of us living in the US, our financial identities are defined by our ratings with the three big credit reporting agencies: Experian, TransUnion and Equifax. Although Experian also operates in the UK, if you live elsewhere in the world you may need to do some searching to discover the credit monitoring scheme for your locality. In general, wherever you live, you should be able to request a copy of your particular credit rating document and should do so annually.

In the US, to protect your financial identity there are a few simple steps. First, check your credit report each year to make sure that your profile information is correct. Despite the television commercials advertising free credit reports from a variety of sources, you’ll find that these sources, such as FreeCreditReport.com or CreditExpert.co.uk, won’t give you any information until you’ve subscribed to their services for a fee. The US Federal Trade Commission provides information on getting your US credit report without subscribing to anything; see http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/edu/pubs/consumer/credit/cre34.shtm. Consumers in other countries can follow a similar procedure, depending on how their credit ratings are maintained. By taking the time to request your information from your local credit agencies each year you can keep an eye on whether your information has been tampered with and who has been accessing it.

In the final analysis, you alone must take responsibility for anything that you upload to an SNS, as well as for how you link your various online identities together. All of the tips and tricks in the world can’t substitute for good judgement concerning what you decide to share. Take charge of managing your digital footprint by carefully assessing what you want people to see. Become adept at tweaking your privacy settings within any SNS profile that you maintain. Trust no one you ‘meet’ online and be very picky about who you allow to befriend you. If you value your online privacy and the rights to your online identity, it is well worth making the effort to keep yourself secure, because, as the not-so-old saying goes, the Internet never forgets.

References

Anna, An introduction to LinkedIn privacy and security [blog post] Retrieved from. 2011. http://safeandsavvy.f-secure.com/2011/09/23/inkedin-privacy-and-security/

Barkah, A., Security issues with Google docs [blog post] Retrieved from. 2009. http://peekay.org/2009/03/26/security-issues-with-google-docs/

Castells, M. The Power of Identity; vol. 2. John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, NJ, 2009.

Debatin, B., Lovejoy, J.P., Horn, A., Hughes, B.N. Facebook and online privacy: attitudes, behaviors, and unintended consequences. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2009; 15:83–108.

Facebook, Data use policy Retrieved from. 2011. https://www.facebook.com/about/privacy/

Ads, Facebook, Isotope twothirtynine Retrieved from. 2011. http://www.facebook.com

Feizy, R., Wakeman, I., Chalmers, D., The transformation of online representation through time in relations to honesty and accountability characteristics Retrieved from. 2010. http://www.sussex.ac.uk/Users/dc52/infweb/Papers/asonam-2009.pdf

Gantz, J., Reinsel, D. Extracting Value From Chaos. Framingham, MA: IDC; 2011.

Gavison, R.E., Privacy: legal aspects 1987. Retrieved from SSRN. Blackwell Encyclopedia of Political Thought. 2011, 13 July:400–401. http://ssrn.com/abstract=1885008

Google, Google privacy policy. 2011. Retrieved from. http://www.google.com/intl/en/privacy/privacy-policy.html

Hampton, K., Goulet, L.S., Rainie, L., Purcell, K., Social networking sites and our lives. 2011. Retrieved from. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Technology-and-social-networks/Summary.aspx

The Innovative Educator, Discover what your digital footprint says about you [blog post]. 2011. Retrieved from. http://theinnovativeeducator.blogspot.com/2011/08/discover-what-your-digital-footprint.html

Kallas, P., Top 10 social networking sites by market share of visits Retrieved from. 2011. http://www.dreamgrow.com/top-10-social-networking-sites-by-market-share-of-visits-august-2011/

Ketabchi, F., Digital footprint and virtual social influence [blog post] Retrieved from. 2010. http://java.sys-con.com/node/1312494

Mac, A., 5 tips to separate personal and professional life online Retrieved from. 2011. http://www.fastcompany.com/1754431/5-tips-to-separate-personal-professional-life-online

Madden, M., Fox, S., Vitak, J., Smith, A., Online identity management and search in the age of transparency [report] Retrieved from. 2007. http://pewresearch.org/pubs/663/digital-footprints

Neal, D., Williams, L.Y. The digital aggregated self: a literature review. Unpublished manuscript, The University of Western Ontario. Kaplan University: London, ON; 2009. [Ft Lauderdale, FL.].

Neal, D., Williams, L.Y. The ethical concerns of data mining: the aggregated self. Paper presented at the The Fifth International Conference of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences. Cambridge: UK; 2010.

O’Donnell, A., Who’s following your child on Twitter? Retrieved from. 2011. http://netsecurity.about.com/od/newsandeditorial1/a/Whos-Following-Your-Child-On-Twitter.htm

Opsahl, K., Six things you need to know about Facebook Connections Retrieved from. 2010. http://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2010/05/things-you-need-know-about-Facebook

Plaisant, C., Shneiderman, B., Baker, H., Duarte, N., Haririnia, A., et al. Personal role management: overview and a design study of email for university students. In: Kaptelinin V., Czerwinski M., eds. Integrated Digital Work Environments: Beyond the Desktop. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005:143–213.

Rozuel, C. The moral threat of compartmentalization: self, roles, and responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics. 2011; 102:685–782.

Rusli, E., Extension lets you hack into Twitter, Facebook accounts easily [blog post] Retrieved from. 2010. http://techcrunch.com/2010/10/24/firesheep-in-wolves-clothing-app-lets-you-hack-into-twitter-facebook-accounts-easily/

Sophos, Facebook security best practices Retrieved from. 2011. http://www.sophos.com/en-us/security-news-trends/best-practices/facebook.aspx

Weaver, S.D., Gahegan, M. Constructing, visualizing, and analyzing a digital footprint. Geographical Review. 2007; 97(3):324–374.

Webster, J., The Duchess of Malfi [electronic book] Retrieved from. 2000 [1623]. http://www.gutenberg.org/catalog/world/readfile?fk_files=1448279

Williams, L.Y., Neal, D.R. Disaggregated informational ownership: recommendations from the literature. Paper presented at the Cyberspace Law and Education Conference. Oxford: UK; 2009.