Research and teaching in real time: 24/7 collaborative networks

Abstract:

The work of academics has radically changed since the introduction of social media tools. One area that has received considerable attention is that of real-time technologies for communication and collaboration. Academics can use tools such as Google Docs, Skype and Dropbox to facilitate the exchange of information, the dissemination of research findings and the creation of new knowledge in real time. The present chapter examines the concepts, theories and key study findings in the area of real-time technologies to show how these tools are being used in the academic setting. Despite the many advantages of using real-time tools for both collocated and dispersed collaborative work, some concerns have been raised about the potential negative effects on productivity and scholarship. I discuss both the advantages and problems associated with the use of real-time collaborative tools and outline strategies for effective implementation.

Real-time technologies for academics

Communication has always been an essential part of academic work – both for research and teaching – because it represents an important means of sharing ideas, collaborating, consulting with colleagues and disseminating research findings. With the diffusion of social media amongst faculty and students, we have witnessed major changes in how academics communicate and collaborate (Bonetta, 2007; Quan-Haase and Young, 2010). While not all academics are equally enthusiastic about the move toward digital communication, a large proportion is finding creative ways of connecting with collaborators and students, discussing important topics, obtaining feedback and disseminating their research findings. Not only that, in a widely cited blog, Dave Parry has stated that the more scholars associate themselves with social media, the more benefits they will derive ‘[n]ot because social media is the only way to do digital scholarship, but because I think social media is the only way to do scholarship period’ (Parry, 2010, para. 14). There is a clear sense that social media is not just a buzzword, but rather is a phenomenon that is here to stay and will fundamentally impact the work of academics.

A number of different tools are aggregated under the rubric of social media, including microblogging, blogs, social networking sites and video sharing and streaming websites (Hogan and Quan-Haase, 2010). Nonetheless, not all social media support the same kind of functionality, with each type providing diverse features and thereby fulfilling different scholarly needs. Digital tools that fall under the designation of real-time technologies have become widely used among scholars because they facilitate communication and collaboration by allowing for the rapid exchange of messages, the emulation of in-person conversations, the reaching of large and diverse audiences, the simultaneous co-editing of text and other data and real-time access to ideas and feedback. Real-time communication and collaboration has indeed become a large part of the daily work of many academics and has the potential to lead toward innovation.

Three current trends make real-time technologies increasingly relevant for academics in terms of teaching and scholarship. The first is the move from localized collaborative clusters to large-scale, networked partnerships spanning regionally, nationally and internationally. This has further pressed the need for real-time digital tools to aid with communication, coordination and collaboration. The second trend is the quick growth of distance education in most universities, which calls for the integration of innovative tools to maintain a high level of student engagement and collaboration (Haythornthwaite and Andrews, 2011). Beldarrain (2006) has stressed the importance of integrating real-time technologies into education, seeing the value in particular for distance courses and degrees that take place only online with little to no physical contact with students. The third trend is the increasing reliance of college and university students on social media tools to accomplish school-related tasks, necessitating a better understanding of how ‘to motivate, cultivate, and meet the needs of the 21st-century learner’ (ibid., p. 140).

In this chapter, an overview of real-time technologies for communication and collaboration in academic settings is provided by focusing on the two core areas of research and teaching. The aim of this chapter is not only to present the advantages, but also to investigate some of the problems and detrimental effects related to the reliance on these tools. In the final discussion, the chapter compares various real-time technologies and shows what strategies the literature has identified for users to effectively integrate these technologies into their work practices.

The concept of real time

Real-time technologies can be defined as those tools that allow for instant communication and collaboration with multiple individuals located nearby or far away via data exchange of voice, text and image (Quan-Haase, 2010). What constitutes real time has been closely tied to the limitations of the technology itself. In the past, delays of as much as 10–15 seconds were considered acceptable. However, recent technological developments have changed our understanding of what constitutes real time, with programs such as Google Docs allowing for immediate updates with basically zero delay (Berlind, 2010).1 From a collaboration point of view, this creates a sense of high levels of work integration among project members.

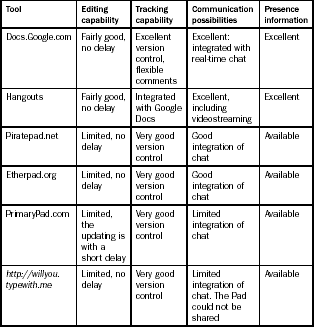

Real-time technologies are distinguished between those that support communication and those that support collaborative work. It is important to make this distinction as the first type facilitates conversations via voice, video and text, while the second type primarily facilitates exchanging, editing and visualizing data (e.g., text, sound and image). Skype is a good example of a real-time communication technology, while Google Docs is a prototype of a real-time collaborative tool. Some platforms integrate both communication and collaboration features allowing participants to work jointly on data and communicate through the same interface about their work (see Table 3.1 on p. 45); the communication in this case represents a meta-level of work (Quan-Haase, 2009).2

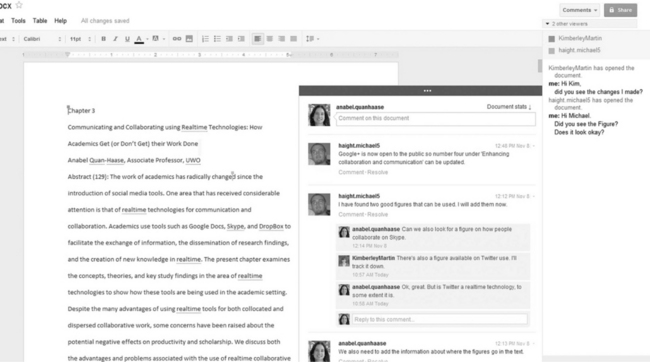

Key features that distinguish real-time digital tools from other tools include the immediacy of messages and updates and the inclusion of tracking tools (Quan-Haase et al. 2005). Another central feature of real-time digital tools is that they signal the presence and availability of other users by displaying notification regarding whether a contact has logged in or logged out. For instance, Facebook provides information about a user’s current login status by displaying in the chat window a green dot next to those users who are logged into the site. This information is necessary to identify potential communication partners. In Google Docs, information is provided about who else is viewing a document through a display of active collaborator names (see Figure 3.3 on p. 46). These unique features of real-time digital tools facilitate both distance and collocated collaboration and communication in digital environments.

Real-time technologies and research

Research projects are moving from localized collaborative clusters to large-scale, networked partnerships with collaborators from other regions. As projects are distributed, these necessitate means for team members to come together virtually to discuss project goals, procedures and milestones. For these distributed teams it is also important to engage in brainstorming sessions and to be able to prototype at a distance. The speed of interaction, display of availability information and support for multiple conversations has made real-time technologies an appealing tool for supporting the work of distributed teams. In a study of how students on campus use real-time technologies, it was found that they often coordinated tasks and helped each other with writing assignments by chatting and exchanging files via instant messenger applications (Quan-Haase and Collins, 2008). Chat provides an informal, spontaneous means of communication that allows collaborators to ask quick questions and obtain prompt clarifications, and coordinate and schedule meetings (Nardi et al., 2000). Further advantages include the ability to negotiate social accessibility, conduct intermittent conversations and maintain a sense of connection with others in the project, even without necessarily communicating (ibid.; Quan-Haase and Collins, 2008).

Skype is the most commonly used real-time technology for one-to-one and group meetings because it is free, easily accessible from any computer/mobile device and supports text, audio-only and video chat. Another useful feature of Skype for collaborative purposes is the possibility of desktop sharing. This allows communication partners to see each other’s desktops in real time and manipulate data at a distance. Skype desktop sharing can be useful for various tasks, such as computer support and maintenance, design work and collaborative writing and editing (Kendrick, 2009). Skype Premium offers group video-calling, allowing two or more people to converse, with the key advantage of the premium edition being that each individual can see all the other parties on a single screen.3 A recent partnership with Facebook has now also integrated videostreaming into Facebook, allowing users to connect in real time on yet another platform.

Skype has also become an important research tool because scholars frequently use it for interviewing purposes. When it is difficult to interview participants face-to-face because of scheduling conflicts or pricey travel, it can be convenient to use Skype as a means to reach them. Because of the video feature, participants’ nonverbal cues are not missed as would be the case in a telephone interview, and additionally it has no long-distance charges. A major deterrent to using Skype has been the inconsistent sound and video quality, making it difficult to predict how useful Skype will be as a reliable tool for hosting collaborative meetings and for data collection purposes.

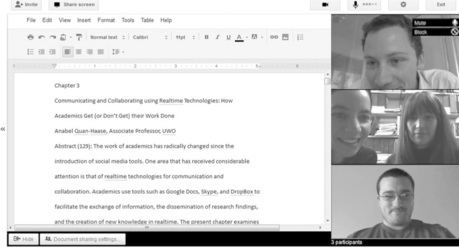

The recent addition of Google+ provides the option of creating a virtual ‘hangout’, where users can be online on videostream. Hangouts can either be public or private. Public hangouts are announced at http://gphangouts.com/, where detailed information is provided about when the hangout will start, the topic and who can participate. These provide open forums of communication for anyone who is interested in a topic to join. Public hangouts also provide new venues for researchers to disseminate their research findings to the larger community, while allowing for input and feedback from the participants. Private hangouts require participants to be added to the hangout and can be used for team meetings. A useful feature in hangouts is the possibility to share, look at and edit documents. Figure 3.2 shows how the SocioDigital Lab (http://sociodigital.info) is sharing and editing a document in real time on the main screen while simultaneously engaging in a discussion. One limitation is that no more than 10 people can join a hangout at any point in time, drastically restricting the number of individuals who can actively participate (see the discussion on scalability below).

Being able to co-write and co-edit documents (text, spreadsheets, presentations, drawings, etc.) in real time has become an important part of many projects. Even though collaborative projects are much more prevalent in the sciences, they are also becoming increasingly common in the social sciences and humanities. A wide range of open source, free software is available on the web to support collaborative writing, analysis and drawing. The most commonly used and developed tools are collaborative writing tools, which allow users to see the same text, edit it and import/export it from the screen. Table 3.1 shows several writing tools and compares their features.

One of the most widely used collaborative writing tools is Google Docs, which is an application that can be accessed via a Google account and allows users to create documents, spreadsheets, drawings and presentations online at no cost. One of the most widely used Google Docs applications provides basic word processing functions, including composition, editing, formatting and printing. Also useful for scholars is the ‘Google forms’ feature (accessible via Google Docs), which allows the design of online surveys and provides a means to collect participant responses. Files created with Google Docs are located in the cloud and, as a result, can be accessed from anywhere. One key advantage of the Google Docs platform is that it allows for multiple editors to work on a single document simultaneously with near up-to-the-second responsiveness (see Table 3.1 above and Figure 3.3).

Revision control or version control is the term used to describe the problems that arise from keeping track of changes made to a document by multiple authors. To prevent such problems, various new digital tools provide safeguards to control and coordinate updates (see Table 3.1 above). For instance, SketchPad.com has a feature that allows the reviewing of the history of the document. Through this feature, the system shows users a true visualization of how the document has evolved. This is a useful way of keeping track of changes, but can also be overwhelming when many versions of a single document exist. The introduction of the real-time feature called ‘presence’ in Google Docs, which shows the location of other collaborators’ cursors (in different colours) has been a useful tool for dealing with revision control and for being able to monitor changes collaborators make to a file in real time (Berlind, 2010). The feature allows for multiple parties to work simultaneously on a document without interfering with collaborators’ writing and editing.

Data in these collaborative writing systems are located in the cloud and, as a result, a number of privacy concerns have emerged. While data in the majority of systems cannot be accessed by others without access privileges, it is nonetheless located on servers in the US or in undisclosed locations. As data fall under the laws of the country where the servers are being hosted this can cause major problems and conflicts in terms of data protection and data privacy (see Chapter 10, this volume). These concerns are of particular relevance to projects that collect, manage and analyse data from participants, and to those projects that include patents, proprietary data or confidential information. Most ethics review boards will not allow for participant data to be collected in the cloud unless the necessary precautions have been put in place (e.g., guaranteed anonymity of responses).

New tools are also emerging that allow for collaboration across projects. At the 2011 Open Science Summit a number of new forms of collaboration were introduced.4 One of these was Science Exchange, which Nature has described as the eBay of Science because it allows project members to post research problems on a site and then other academics, institutions and organizations can bid on these entries to aid with identifying a solution.5 This helps academics with particular research needs to connect with other research clusters and seek help specific to their projects in real time.

Real-time technologies and teaching

Adding real-time technologies as another form of student engagement provides more options for out-of-class communication and interaction with faculty. Not surprisingly, some of the top American schools have moved towards real-time applications such as Google Docs. Sixty-one of the top 100 US universities in 2011 used Google Apps to facilitate communication and collaboration among students and faculty (Google Enterprise Blog, 2011).6 While many of the privacy concerns that arise from this move toward cloud computing have not been addressed sufficiently, the reliance on these apps in educational settings seems to be increasing. What often motivates the move toward real-time technologies is educators’ aspiration to increase student–faculty interaction and student engagement (Dobransky and Bainbridge Frymier, 2004), therefore providing communication and collaboration alternatives that are flexible and suit students’ needs.

Several attempts have been made to integrate real-time communication tools into the learning environment. Balayeva and Quan-Haase (2009) used MSN Messenger as a means to hold weekly office hours with the aim of increasing student–faculty interaction. These virtual office hours were offered in addition to in-person office hours. While the study showed an increase in interaction, respondents reported some apprehension with using only chat for communicating with their instructors because conversations progressed slower than those taking place in person and did not allow for the discussion of complex questions and topics. These characteristics of chat can lead to misunderstandings that are difficult to disambiguate. Therefore, the authors have argued that chat can supplement (not replace) email and its key advantage is to fill communication gaps between face-to-face communication. Research by Roper and Kindred (2005), also on the use of chat for out-of-class communication, shows that the ‘tone of the messages was friendly and polite, much like how one would act if stopping by the office or calling on the phone’ (Roper and Kindred, 2005, discussion section, para. 3). This suggests that real-time technologies could be useful to support some aspects of student–faculty interaction and collaboration.

The rapid growth in distance education has created a need to better support students who rely only, or primarily, on virtual communication. The majority of online course management tools integrate real-time tools, allowing students to communicate with one another as well as with the instructor. The most commonly used tool is chat but some course management tools also allow for video- and voice-streaming. These real-time tools can assist in increasing the frequency, and perhaps quality, of in-class and out-of-class communication.

Choosing a real-time technology

In addition to the broad categorization of real-time tools into those supporting communication and those supporting collaboration, several dimensions have emerged as central when making decisions about which tools are best suited for a project or course. Next, I will discuss in more detail four key dimensions:

Network type. Digital tools that are geared towards closed network structures support communication and collaboration among a small group of scholars who share a common affiliation or are clustered together in a meaningful way (e.g., a research cluster, the members of a lab, or students taking a course). Skype and Google Docs are two tools that best support closed network structures, as only those interlocutors who are in a user’s contact list can communicate with one another. In comparison, open network structures are those that support communication and collaboration between people who may or may not know each other or at least are not formally associated. One example of this type of real-time technology is Google+ Hangout, where any user can join a hangout, as long as they have a Google account, a webcam and a microphone. In general, real-time digital tools tend to support closed network structures because even a minimal level of acquaintance is needed for two individuals to feel comfortable contacting each other spontaneously in real time (Quan-Haase et al., 2005).

Scalability. Scalability7 refers to the extent to which a tool is designed to effectively support the work of a larger group of users. Tools may be limited in their ability to scale out to larger groups. These limitations may result from technological constraints or from the affordance of the tool. Some tools have been developed to facilitate contact between small groups ranging from two to five individuals. Even though Google Chat has no limit to the number of people that can be added, it is best suited for conversations among two to five individuals; once more than five individuals are added to the chat, it is difficult to keep track of who is conversing, and making sense of a conversation that includes more than six people is almost impossible (i.e., unless some users are not participating). In general, asynchronous forms of communication are better suited to scale out (i.e., adding more users to the system) because it is easier to track who is leaving a message and also follow the evolution of a conversation. Herring (1999) found in her analysis of text-only computer-mediated communication (e.g., Internet Relay Chat) that the negative effect of incoherence was offset by the availability of a persistent textual record that could help communication partners make sense of messages. This is also true of chat, where conversation partners can scroll up to see text previously typed to help them make sense of the conversation, but has its limitations once the conversation moves too quickly and consists of too many interlocutors.

Data type. Real-time technologies support the exchange of different types of data, including voice, image, text and multimedia. While some tools are geared toward transmitting and sharing a single type of data, others allow for multi-modal exchanges. For example, Google Docs primarily supports collaboration in a textual environment. By contrast, Skype is multi-modal in nature: providing visual and auditory information on the interlocutors, and having a window for simultaneous text, file and image sharing.

Push vs. pull. Push technology displays information without any action being required from the user, whereas pull technology necessitates users to seek out updates. Instant messaging is a push technology because presence information about other users is automatically transmitted without the user needing to request the information. In push technology, users can also choose to display availability through the use of status settings (e.g., busy or away), or they can leave messages to others about their social accessibility by way of customizable messages (Baron et al., 2005; Quan-Haase and Collins, 2008). Therefore, chat provides a variety of ways in which to display a user’s presence and availability in a flexible manner over time. In pull technology, users are required to seek out information about other users. In Google Docs, for instance, users need to select the ‘revision history’ to see the changes made to a document by collaborators. These updates are not automatically presented to the user. It is clear from this distinction that it is useful to have both push and pull technology in place to more effectively manage information overload (Baron, 2008; Quan-Haase, 2010).

Challenges using real-time technologies

As students and faculty adopt real-time technologies, it is becoming evident that these also have potential negative consequences. These detriments are often summarized under the term productivity paradox, which is defined as ‘a phenomenon in which investments in the use of information technology have not resulted in productivity improvements’ (Hannula and Lönnqvist, 2002, p. 83). In this section, six potential negative consequences are discussed that have been identified in the literature.

Losses in productivity. The concerns raised in the literature are primarily linked to losses in productivity that can result from multitasking (Gonzalez and Mark, 2004; Su and Mark, 2008), workflow interruptions, shifts in attention and loss of focus (Cutrell et al., 2001; Quan-Haase, 2010). Quan-Haase and Collins (2008) argue that the social norms of real-time technologies lead users to reply quickly because others know they are available for communication, even when it may be disruptive. When people are ‘always on, always available’, it makes it difficult to keep focused on a task (Quan-Haase et al., 2005).

Information overload. Similar to concerns considered in other learning infrastructures, the increased volume of communication caused by real-time technologies requires management (Oua and Davison, 2011). When used to engage with students for out-of-class communication, these tools can add considerable effort to a faculty member’s workload (Balayeva and Quan-Haase, 2009). For e-learning initiatives this increased volume of messages between faculty and students may be a desired outcome. In large traditional classrooms with over 100 students, an increase in volume may represent an unnecessary burden for the instructor, particularly if no teaching assistants have been assigned to the course. This shows that practical implications need to be taken into consideration prior to adoption. The use of real-time technologies to communicate with collaborators may, on the other hand, be an effective way to exchange messages without adding considerably to the regular workload when used effectively.

Lack of nonverbal cues. Karpova et al. (2008) identify numerous challenges associated with virtual collaborations. The authors see some disadvantages because ‘the inability to use nonverbal language in virtual communication made the interaction more challenging’ (p. 49) and can lead to misunderstandings and slow down progress. This common reoccurring theme throughout the research in this area shows that text-only learning environments may constrain the kinds of interactions that are possible (Finegold and Cooke, 2006). Nonetheless, the widespread adoption of Twitter among academics – which is not only a text-based tool, but restricts posts to 140 characters – suggests that the lack of nonverbal cues can be beneficial for certain scholarly communities and scholarly purposes.8

Awareness of responsibilities. Another significant hurdle faced by virtual teams is the absence of clear team-based working processes (Karpova et al., 2008; Leinonen et al., 2005). Teamwork involves the collaboration of a number of individuals who all participate in the process of creation. However, it is essential that all members of the team are aware of the other members’ responsibilities. Previous research shows that the role of awareness in virtual collaboration is an important issue, the lack of which certainly can inhibit productive and creative teamwork (ibid.).

Loss of privacy and control over data. Even though many users express concerns about how real-time technologies represent an invasion of privacy, this does not usually deter them from using them (Young and Quan-Haase, 2009). The attitude expressed by most users is that as long as they have not had any negative experiences themselves, they do not see a need to proactively protect their data. There are two kinds of potential threats to privacy in the use of real-time technologies, one is social and the other is institutional (Raynes-Goldie, 2010). Social privacy refers to the risks associated with friends, colleagues or acquaintances finding out personal information that users may not want to disseminate. Institutional privacy describes the loss of privacy on a more structural scale; for instance, companies who provide online services potentially sharing data with third parties or aggregating data from various sources. Both kinds of loss of privacy represent a major problem as data are not locally stored but are rather on the cloud9 and therefore they fall under different jurisdictions.10

Relationship type. The use of real-time technologies is most appropriate for supporting interactions among close-knit networks (Quan-Haase et al., 2005). For collaborative and teaching purposes, trusting relationships are an important factor for real-time technologies to work efficiently. Wymer, in her study, made herself available for consultation to students via virtual office hours using chat and her experience made her ‘question the extent to which our students want us to reach out to them in those new ways’ (2006, pp. 37–8). Part of the problem is that students use social media to ‘express themselves and their individuality’ (ibid.) and might not feel comfortable letting faculty into their personal world. Balayeva and Quan-Haase (2009), in a similar study, asked students how comfortable they were communicating with instructors via chat. The results showed that 10 per cent of students felt uncomfortable communicating with faculty via chat because of the type of formal relationship they have with them. While students may not feel comfortable adding faculty to their personal Facebook pages, they may welcome opportunities to talk to them in real time when supported by a formal system (such as edmodo.com). Therefore, it is important to obtain a better understanding of the unique features of various real-time tools and how to design them so that they will better serve student and faculty needs. These options are further explored in Chapter 8.

Conclusions

An important question when examining different types of real-time technologies is the appropriateness of different tools for various types of collaborative networks and class settings. The duration of projects, the amount of interaction needed and the interdependence of tasks are all important considerations when making choices about which real-time tools are most suitable. Also, different classroom settings, ranging from smaller classrooms or seminars with about 20–30 students to large classrooms, may necessitate different approaches. In smaller classrooms, where the faculty know all of their students, real-time communication may enhance interaction and engagement with the material. In large classrooms, the number of real-time interactions may become so large that it becomes a burden for faculty. Future research needs to compare the use of various real-time technologies in different kinds of settings.

As Generation Y (also known as the Millennial generation) continues to move into academic settings, it will become critical for faculty to obtain a grasp on how this cohort uses real-time technologies and the social and productivity implications this use will have on their work habits and scholarship. A study by the Pew Internet & American Life Project found that Generation Y is more likely to rely on the Internet for communicative, creative and social uses; for example, showing significantly more social media usage than other generations (Lenhart et al., 2010; Madden and Smith, 2010).

Real-time technologies offer many benefits to academics. However, the resulting work environment of ‘always on, always available’ also represents a number of challenges. On the one hand, the advantages of real-time technologies to academics lie in the timeliness of information available and the possibility to connect with colleagues at a distance. The social web continually provides a stream of up-to-date information on relevant topics as well as on developments occurring in the field. The importance of being connected to the field can be of great relevance. On the other hand, a central problem in real-time communication is the disruptive nature of the technology. Various strategies can help users deal more effectively with multitasking, management of virtualization and distractions. This area of study becomes increasingly relevant because today’s work practices are undergoing changes due to the ongoing development of social media (Rennecker and Godwin, 2003). While concerns remain as to the consequences of real-time technologies, the need for adoption to collaborate, disseminate research findings and reach a larger, diverse audience is inherently evident.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from an Academic Development Fund from the University of Western Ontario and GRAND, a Canada Network of Centres of Excellence grant. The manuscript has greatly benefited from the input of Michael Haight and Kim Martin, students in the SocioDigital Lab at the University of Western Ontario.

References

Balayeva, J., Quan-Haase, A. Virtual office hours as cyberinfrastructure: the case study of instant messaging. Learning Inquiry. 2009; 3(3):115–130.

Baron, N.S. Always On: Language in an Online and Mobile World. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Baron, N.S., Squires, L., Tench, S., Thompson, M. Tethered or mobile? Use of away messages in instant messaging by American college students. In: Ling R.R., Pedersen P.E., eds. Mobile Communications: Renegotiation of the Social Sphere. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2005:293–311.

Beldarrain, Y. Distance education trends: integrating new technologies to foster student interaction and collaboration. Distance Education. 2006; 27(2):139–153.

Berlind, D., First look: Google docs gets realtime collaboration. Information Week 2010; 15 April. Retrieved from. http://www.informationweek.com/news/software/productivity_apps/224400349

Bonetta, L. Scientists enter the blogosphere. Cell. 2007; 129(3):443–445.

Cutrell, E., Czerwinski, M., Horvitz, E., Notification, disruption, and memory: effects of messaging interruptions on memory and performance In. Proceedings of the Human-Computer Interaction Conference (Interact ’01), 2001. Retrieved from. http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/um/people/cutrell/interact2001messaging.pdf

Dobransky, N.D., Bainbridge Frymier, A. Developing teacher-student relationships through out-of-class communication. Communication Quarterly. 2004; 52(3):211–223.

Finegold, A.R.D., Cooke, L. Exploring the attitudes, experiences and dynamics of interaction in online groups. Internet and Higher Education. 2006; 9:201–215.

Gonzalez, V., Mark, G., “Constant, constant, multi-tasking craziness”: managing multiple working spheres. Dykstra-Erickson, E., Tscheligi, M., ed. Proceedings of the ACM CHI 2004 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, New York, 2004:113–120, doi: 10.1145/985692.9 85707.

Hannula, M., Lönnqvist, A. How the Internet affects productivity. International Business & Economics Research Journal. 2002; 1(2):83–91.

Haythornthwaite, C., Andrews, R. E-learning Theory and Practice. London: Sage; 2011.

Herring, S.C. Interactional coherence in CMC. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 1999; 4(4):1–27.

Hogan, B., Quan-Haase, A., Persistence and change in social media: a framework of social practice. Bulletin of Science. Technology and Society. 2010;30(5):309–315 Retrieved from. http://bst.sagepub.com/content/30/5/309.full.pdf+html

Karpova, E., Correia, A.-P., Baran, E. Learn to use and use to learn: technology in virtual collaboration experience. Internet and Higher Education. 2008; 12:45–52.

Kendrick, J., Collaboration with Skype desktop sharing: the best free method? Gigaom 2009; Retrieved from. http://gigaom.com/mobile/collaboration-with-skype-desktop-sharing-the-best-free-method/

Leinonen, P., Järvelä, S., Häkkinen, P. Conceptualizing the awareness of collaboration: a qualitative study of a global virtual team. Computer Supported Cooperative Work. 2005; 14:301–322.

Lenhart, A., Purcell, K., Smith, A., Zickuhr, K., Social media and young adults. The Pew Internet and American Life Project. 2010 Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Social-Media-and-Young-Adults.aspx

Madden, M., Smith, A., Reputation management and social media. The PEW Internet and American Life Project. 2010 Retrieved from. http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Reputation-Management.aspx

Nardi, B.A., Whittaker, S., Bradner, E., Interaction and outeraction: instant messaging in action In. Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW). ACM, New York, 2000:79–88, doi: 10.1145/358916.358975.

Oua, C.X.J., Davison, R.M. Interactive or interruptive? Instant messaging at work. Decision Support Systems. 2011; 52(1):61–72.

Parry, D., Be online or be irrelevant [blog post]. 2010. Retrieved from. http://academhack.outsidethetext.com/home/2010/be-online-or-be-irrelevant/

Quan-Haase, A. Information Brokering in the High-tech Industry: Online Social Networks at Work. Berlin: LAP Publishing; 2009.

Quan-Haase, A. Self-regulation in instant messaging (IM): failures, strategies, and negative consequences. International Journal of e-Collaboration. 2010; 6(3):22–42.

Quan-Haase, A., Collins, J.L. ‘I’m there, but I might not want to talk to you’: university students’ social accessibility in instant messaging. Information, Communication & Society. 2008; 11(4):526–543.

Quan-Haase, A., Cothrel, J., Wellman, B., Instant messaging for collaboration: a case study of a high-tech firm. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2005;10(4). Retrieved from. http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol10/issue4/quan-haase.html

Quan-Haase, A., Young, A.L., Uses and gratifications of social media: a comparison of Facebook and instant messaging. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society. 2010;30(5):350–361 Retrieved from. http://bst.sagepub.com/content/30/5/350.abstract

Raynes-Goldie, K., Aliases, creeping, and wall cleaning: understanding privacy in the age of Facebook. First Monday. 2010;15(1). Retrieved from. http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/viewArticle/2775

Rennecker, J., Godwin, L. Theorizing the unintended consequences of instant messaging productivity. Sprouts: Working papers on Information Environments, Systems and Organizations. 2003; 3(3):137–168.

Roper, S.L., Kindred, J., ‘IM here.’ Reflections on virtual office hours. First Monday. 2005;10(11). Retrieved from. http://www.ischool.utexas.edu/~i385q/readings/firstmonday_im.htm

Su, N.M., Mark, G., Communication chains and multitasking. Czerwinski, M., Arnie, L., Desney, T., ed. Proceedings of the ACM CHI 2008 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. ACM, Florence, Italy, 2008:83–92.

Wikipedia, Scalability. 2011. Retrieved from. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scalability

Wymer, K., The professor as instant messenger. The Chronicle of Higher Education 2006; 7 Retrieved from. http://chronicle.com/article/The-Professor-as-Instant/46916

Young, A.L., Quan-Haase, A., Information revelation and internet privacy concerns on social network sites: a case study of Facebook. Carrol, J.M., ed. Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Communities and Technologies. Springer Verlag, Dordrecht, 2009:265–274.

1Google Documents or Google Docs is owned and managed by Google. Even though the term Google Docs may suggest that it refers only to word processing files, it is actually used more broadly including spreadsheets, presentations, tables, and drawings.

2The term meta-level of work refers to a conversation about the work that is taking place in the real-time collaborative environment as it unfolds.

3In October 2011, the price for Skype Premium was USD$4.49/month.

4The Open Science Summit is a conference dedicated to using distributed innovation to address pressing needs in academia.

5See the article at: http://www.nature.com/news/2011/110819/full/news.2011.492.html.

6The Google Enterprise Blog is located at: http://googleenterprise.blogspot.com/2011/09/tradition-meets-technology-top.html.

7Scalability is defined as ‘the ability of a system, network, or process, to handle growing amounts of work in a graceful manner or its ability to be enlarged to accommodate that growth’ (Wikipedia, 2011, para. 1).

8See Chapter 2 of this volume on scholarly communities.

9This is an inherent benefit of cloud computing as the data can be retrieved from any location.

10See Chapter 10 in this volume.