SECTION III

Explanatory perspectives

CHAPTER 7

Legal responsibilities for industrial emergency planning in the UK

Introduction

The English legal system tends to be re-active rather than pro-active. This generality certainly applies to its approach to the setting up of systems for accident prevention and damage control.

When an accident has occurred the victims who suffer personal injury or damage to property, may bring civil actions for damages; possibly, but less probably, there may be prosecutions, especially if the accident has caused death. The common law system, which originated in England but is now the paramount influence throughout the whole of the United Kingdom, made little or no provision for accident prevention. It has always been exceptional for judges to grant individuals injunctions to prevent others from acting in such a way as to cause damage (see e.g. Gouriet's Case), and the common criminal (1977) law, in contrast to the legal systems in other European countries, does not recognise a general offence of, and impose penalties for, endangering life.

Common law of homicide

Further there has been a reluctance to convict under the general criminal law when personal injury, even death, has been accidentally caused: there are very few examples of convictions for manslaughter where death has occurred as a result of industrial activity or in transportation accidents.

There are cases, e.g. R v Pittwood [1902], where a railway crossing gatekeeper was convicted of manslaughter when death was caused by his failure to keep the gate closed. See also The Times 7 September 1989, p 1: under ‘Rail crash driver is charged’ –

‘The driver of the express train that crashed at Purley, Surrey in March, killing five passengers and injuring 87 others, was charged yesterday with manslaughter.’

He was also apparently charged under the Offences Against the Person Act 1861, section 32, with endangering the safety of railway passengers, an unusually statutory exception to the general lack of liability for endangering life. However, the difficulty in securing convictions for manslaughter was again highlighted when, in the autumn of 1990, in relation to the capsize of the Herald of Free Enterprise, Mr. Justice Turner withdrew the manslaughter cases against two directors and four employees of P&O European Ferries, from consideration by the jury (see for example the report in the British Safety Council's journal, Safety Management, November 1990, p 6).

However, the reluctance of juries to find drivers of motor vehicles guilty of the offence of manslaughter (which may carry a sentence of life imprisonment) was the prime reason why the statutory offence of causing ‘the death of another person by driving a motor vehicle on a road recklessly’ (bearing a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment) was introduced. This is now section 1 of the Road Traffic Act 1988.

Regulatory offences

The approach of Parliament to safety issues, in attempting to remedy the deficiencies of the judge-made common law, has been to lay duties on individuals, requiring them to observe standards of behaviour, and to impose criminal sanctions on those who break such duties. The intention has been accident prevention and a statutory offence may frequently be committed by someone who creates a hazard, regardless of whether anyone actually suffers injury. For example, compare section 2 of the Road Traffic Act with section 1; under section 2 the offence is committed by driving recklessly, regardless of whether or not any accident is caused.

The statutory approach has been, with the notable, and perhaps necessary, exception of road traffic, to emphasise corporate responsibilities; and duties are principally imposed upon employers. Parliament's approach has, however, traditionally been one of ‘practical empiricism’. The technique of only providing ‘a practical remedy for a proved wrong’ was noted in the context of occupational health and safety legislation nearly a century ago by Sidney Webb. He complained:

‘We seem always to have been incapable even of taking a general view of the subject we were legislating upon. Each successive statute aimed at remedying a single ascertained evil.’ (Hutchins and Harrison 1966.)

Sidney Webb was specifically referring to health and safety in factories, but his words would have been equally true of other workplaces and even more relevant to the interface between occupational and public safety.

The British tradition has been to wait for the catastrophe, hold a public enquiry and legislate piecemeal, in the light of the report, to try to prevent anything like that happening again. Typical of the traditional approach was the legislation which followed the Aberfan disaster (Aberfan Tribunal 1967) in the 1960s, to give coal mine inspectors powers in respect of coal tips: a village had to be engulfed before there was legislation requiring coal tips ‘to be made and kept safe’ (section 1(1), Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969). There are many comparable examples, but Aberfan is relevant because it occurred just before the Robens Committee was set up in 1970 to consider the provision made for the safety and health of persons at work. The Committee reported in 1972 and its recommendations were largely implemented in the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974.

The Committee deplored the traditional pragmatism which had resulted in a piecemeal approach to safety and advocated imposing on management broad responsibilities for identifying, implementing and maintaining safe systems. It also did not find entirely convincing: ‘The general line taken by the inspectorates … that, by and large, if occupational safety regulations are observed the public will automatically be protected.’ (Robens Committee 1972, Chapter 10, para 287.)

It could be said that the Committee proposed extending the concepts of civil liability for accident compensation to the criminal law for the purpose of accident prevention. However it did not address the matter of contingency planning for damage control, to deal with the situations where preventative systems failed to avoid catastrophe. That the Health and Safety at Work Act did create criminal liability comparable with civil liability in similar situations was accepted by the Court of Appeal in R v Swan Hunter [1981]. The criminal court adopted judgements given by the Court of Appeal in McArdle v Andmac Roofing [1967], a compensation case.

Surprisingly the Report made no reference to the statutory schemes for mine disaster rescue, which had been in force since 1910. The relevant legislation is the Mines Accidents (Rescue and Aid) Act 1910; Coal Mines Act 1911, section 85: Coal Mines (Fire and Rescue) Regulations 1914 SR&O 710; now Mines and Quarries Act 1954, section 72 and Coal Mines (Fire and Rescue) Order 1956 SI 1768. This legislation imposed a duty on mine owners to set up Central Rescue Stations within the coalfields, with trained staff, technical equipment and pre-disaster organisation adequate to minimise the consequences of mine disasters. Nor did the Robens Committee even refer to the then new provisions of the Mines and Quarries (Tips) Act 1969, which imposed duties upon mine owners and local authorities to assess the potential dangers to the public from tips, and to take the necessary remedial action (section 11, section 12, section 14 and section 17–section 18). While this legislation relates only marginally to the idea of contingency planning, the mines rescue scheme clearly contains the elements of such planning, as well as making the necessary provisions for fire-fighting and rescue of personnel.

When the Robens philosophy was adopted by Parliament in the Health and Safety at Work Act the era of legislative pragmatism should have been brought to an end. Ideally management would anticipate unsafe situations and devise systems to prevent them from causing injury: if organisations failed the legislation would be broad enough to impose liability upon them for their failure. It is questionable, however, whether the broad brush approach of the Act could be said to impose any responsibility to plan for damage control in emergency situations, either for the protection of the work force or for the protection of the general public.

The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974

Broad approach of the Act

The primary objective of the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 was to secure the health, safety and welfare of persons at work (section 1(1)(a)): in itself a very wide objective, since it meant the Act was to apply to all work situations within Great Britain, thus making provision for many workers who had previously been without statutory protection. The application of the Act has now been extended to Northern Ireland and (Infra) to offshore installations on the North Sea continental shelf.

However the Act's provisions were also intended to have effect with a view to –

‘protecting persons other than persons at work against risks to health or safety arising out of or in connection with the activities of persons at work’ (section 1(1)(b)).

This particular objective was novel for employment protection legislation: it meant that henceforth employers had to have regard not only for the health and safety of their own employees but also for that of other workers and even for the safety of the general public.

Both of these objectives of the Act are reflected in the general duties imposed upon employers in section 2 and section 3 of the Act. Section 2(1) stipulates:

‘It shall be the duty of every employer to ensure so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all his employees.’

Section 3(1) stipulates:

‘It shall be the duty of every employer to conduct his undertaking in such a way as to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that persons not in his employment who may be affected thereby are not thereby exposed to risks to their health or safety.’

There is however nothing expressly in this, and relatively little impliedly either here or elsewhere within the Act, to require employers to plan for management of catastrophes, with regard to rescue and evacuation of personnel and damage control. Section 3(1) in particular reflects the philosophy of the legislation: avoidance of exposure to risks. It is a philosophy which placed its emphasis on catastrophe avoidance, rather than on emergency planning, and within that philosophy the emphasis inevitably remains, in spite of the novel objectives of the legislation, upon protection of the employed workforce, rather than the safety of other workers and the public. It is true that section 3(3) enables regulations to be made to require the employer to give information to persons other than his employees ‘who may be affected by the way in which he conducts his undertaking’ but section 3(3) has yet to be implemented to have general effect. In any case it may be that the sub-section would not support regulations which imposed on employing organisations any positive duty to instruct members of the public in emergency procedures as opposed to merely requiring them to give notification of the risk. However, there is high judicial authority for the proposition that the general duty in section 3(1) does require an employer to supply to the employees of subcontractors working on his premises, the same safety manual as he supplies to his own employees, in order that the visiting workers may endanger neither themselves nor the employer's own employees (see R v Swan Hunter). As a result, section 3 is invaluable in imposing upon contractors the duty of coordinating the activities of their sub-contractors, so that their work relates safely both to the work undertaken by the contractor himself and to any other work which he has contracted to other sub-contractors.

Emphasis on employee safety

The main thrust of the Act being the employer's duty to provide for the safety of his own employees while they are at work, the Act spells out in some detail the systems approach which the employer is expected to adopt for the protection of his workforce. Section 2(2), which is stated to be without prejudice to the generality of the duty set out in section 2(1), enumerates matters which are included in the employer's general duty to his employees. It is arguable that two, at least, of the paragraphs under section 2(2) are relevant to emergency situations. Section 2(2)(d) requires the employer to provide safe means of access to and egress from any place of work and this could be deemed to relate not merely to normal employment but also to evacuation in emergency. (This duty, like most of those imposed by the Act is qualified by the words so far as is reasonably practicable (see Mailer v Austin Rover [1989]).)

Much more significant is section 2(2)(c), which is in many respects one of the most important provisions of the Act, since it relates to human behaviour within, rather than the plant and equipment which make up, the working environment. Section 2(2)(c) requires from the employer:

‘the provision of such information, instruction, training and supervision as is necessary to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health and safety at work of his employees’

But in any event most workplaces, and other buildings where the public are likely to be present in numbers are subject to special fire certification requirements (Fire Precautions Act 1971 as amended, and subordinate regulations), and the fire certificate may well make specific requirements as to training of employees.

There can be no doubt that the implementation of safe systems at the workplace must require employers not only to train their employees in catastrophe avoidance, but also to train them how to respond to the eventuality of catastrophe occurring, to the extent necessary for their own safety. It may therefore be questioned, since the emphasis is on employee safety, whether for example training of shop assistants (or others, such as hotel staff, who serve the public at their workplace) for evacuation of premises in the event of fire or explosion ought, if carried out in strict compliance with section 2(2)(c), to require employees to place themselves at any enhanced risk by delaying their departure to the extent necessary to ensure the safe evacuation of the public as well as of the workforce. It is to be hoped that no court will ever have to balance the duty in section 2(2)(c) against that in section 3(1). One would expect that systems would be devised which enabled evacuation without creating conflict between the safety of employees and others. It is some consolation that in the case of fire, the workplace is likely to be covered by a fire certificate which will stipulate evacuation procedures precisely with a view to resolving such a conflict of priorities.

Provisions relating to other persons

It has, however, been judicially held that section 2(2)(c) requires the employer to make the provision specified in the paragraph to persons other than his own employees if this is necessary in order to ensure that the behaviour of those others does not endanger his own employees. The actual case concerned the system of work to be used when welding in confined spaces and thus established that a head contractor must inform, instruct, train and supervise the employees of a sub-contractor to the extent that this is necessary to protect the head contractor's own employees (R v Swan Hunter). There seems no reason, however, why the ratio of the decision should be confined to the instruction and control of other workers: it would appear to be equally relevant to situations where the visitors to the employer's premises are members of the public. Nevertheless, the employer's duty is qualified by the phrase ‘reasonably practicable’ and, in many instances, such as where the ‘public’ are customers making brief visits to department stores, meaningful instruction as opposed to information is hardly likely to be feasible. In other situations where the same persons albeit members of the public visit frequently, e.g. students at a college, or where a group of visitors is to be present for a length of time, e.g. a party visiting industrial premises, the provision of such instruction could well be within the scope of the paragraph.

A novel duty imposed by that Act is the requirement that the employer produce a safety policy. Section 3(3) states:

‘it shall be the duty of every employer to prepare and as often as may be appropriate revise a written statement of his general policy with respect to the health and safety at work of his employees and the organisation and arrangements for the time being in force for carrying out that policy, and to bring the statement and any revision of it to the notice of all of his employees.’

The significance of this sub-section in making organisations set up and maintain safe systems has not escaped the Health and Safety Executive; inspectorates have placed priority on the existence of safety policies and have expected to find a genuine relationship between the documentation and the actual situation at the workplace. Industrial safety officers have rightly deduced that proper compliance with the sub-section demands that careful attention must be given to the arrangements which exist for dealing both with hazards which are routine to the operation of the enterprise and also for emergency situations which these hazards may create (Barrett et al 1985). Organisations have therefore often committed to paper systems for dealing with these matters.

Special Regulations

In some installations, attention to emergency situations is now required by The Control of Industrial Major Accidents Hazards Regulations (1984 SI No. 1902). Such sites are defined as those where an occurrence (including in particular a major emission, fire or explosion) resulting from uncontrolled developments in the course of an industrial activity, would lead to a serious danger to persons. Where a site constitutes a major accident hazard the manufacturer (‘person’ in control of the industrial activity) is under a statutory obligation to submit to the Health and Safety Executive a written hazard assessment, and provide persons on site with adequate information, training and equipment. In special situations (Regulation 4(2)) the manufacturers must prepare an ‘on site emergency plan’, detailing how major accidents will be dealt with; backed up by an ‘off site emergency plan’ (Regulations 10 and 11) prepared in conjunction with the local authority within whose area the plant is situated. Obligations are also imposed upon the manufacturer and the relevant local authority, for the giving of information to the public as to ‘safety measures’ and ‘correct behaviour’ in the event of a major accident (Regulation 12). However the practice of drawing up such arrangements is apparently more generally observed than the Regulations require. In all cases the challenge is then to ensure that, as section 2 (2)(c), section 2(3) and the regulations all require, employees (and others who are at risk) are trained and, if necessary, disciplined into using these systems.

Relationships with Public Services

The impact of section 2(3), the specific major hazard regulations, and the more general fire certificate requirements (which apply in one form or another to most buildings of any size), is that many employing organisations have informed the emergency services of the potential of their establishments for catastrophe and in the case of some larger establishments it may have been in the interests of all parties to carry out practice exercises to test emergency procedures. In the event, however, of catastrophe, neither the Health and Safety Executive, nor the employer, has any authority over the emergency services, or any remedy against them should they fail in their public duties. This is in accordance with the Robens Committee's recommendation that the safety inspectorate's authority should be related to, rather than impinge upon, the authority of other government departments (particularly the Home Office) in respect of public safety (Robens Committee 1972, paras 293 and 291). It may be significant that the Committee's terms of reference excluded transport activities; the Act did not exclude them specifically and many recent catastrophes have been transport related.

The employer for his part, cannot impose any contractual obligation on any of the public services to provide him with special emergency support. The major emergency services, i.e. fire (Fire Services Act 1947), ambulance (National Health Services Act 1977), police (Police Act 1964), have general obligations in relation to the performance of their services, but seemingly have the right to determine the policy issues relating to the deployment of their resources. The issue has been most tested in relation to the police, where in a series of leading cases the courts have decided that the police have no general duty to protect any particular individual (e.g. Hill v Chief Constable of W. Yorkshire [1987]) and the Chief Constable has considerable discretion as to whether or not police will be deployed in the service of individuals or organisations (R v Chief Constable of Devon and Cornwall [1981]) but may charge for services which are in excess of normal policing activity (Glasbrook Bros v Glams. C.C. [1925]); in some instances even if the situation is one where the special provision is necessary (Harris v Sheffield U.F.C. [1987]). It has similarly been decided that there are circumstances in which a fire authority may charge for providing services outside the area in which is normally operates (Upton-on-Severn v Powell [1942]). The statutory entitlement to charge for a special service rendered does not, however, appear to entitle the person who pays to determine the level of service and, in the case of the police, there is certainly some power to decide whether the service should be supplied at all (Police Act 1964, section 15 ). There is therefore the somewhat unsatisfactory situation that industry may, in discharge of its duties, draw up plans which in the last instance it has no authority to see implemented. However, if it were otherwise, enterprises might be inclined to place too much reliance on the public services and pay too little regard to their own responsibilities: arguably there is some tendency in this direction already. For example it is well accepted that some events, such as major football matches, cannot be held without a heavy police presence to control the crowds and prevent injury through violence or accident. While it is justifiable that private organisations should not have the power to manage, by contract or otherwise, the provision of public services, it is not necessarily justifiable that the public services, in the jealous guarding of their individual powers, have no inclination or obligation (apart from certain situations governed by the Hazardous Installations Regulations, where a duty is imposed on the relevant local authority), to appoint one service as the co-ordinating authority. Delegates at the Fire International ′89 Conference learned that there had been embarrassment at scenes such as the Clapham rail disaster because none of the rescue services had the legal right to assume overall control (The Times, 8 September 1989, p 2 ‘Call for disaster law to be clarified’). The Home Office said the police usually assumed this power.

Conclusions

In conclusion it should be noted that while all persons at work onshore in the United Kingdom are subject to the protection of the Health and Safety at Work Act, not all enterprises and commercial activities are exclusively, or even primarily governed by the Act. A distinction must be made between those work situations which are subject to a second piece of legislation, such as the Factories Act 1961, itself enforced by the Health and Safety Executive (see Schedule of the Health and Safety at Work Act), and other situations where the other legislation, in many cases the legislation of primary importance, is not enforced directly by, or under agency given by, the Health and SafetyExecutive. Notably carriage of persons, by water, road, rail and air are all activities which are governed by legislation, such as Merchant Shipping Acts, Civil Aviation Acts and Road Traffic Acts, enforced by agencies other than the Health and Safety Executive. Interestingly, most of the recent catastrophes have involved premises or activities which are primarily the concern of these other enforcement agencies, and not that of the Health and Safety Executive: the major exceptions being the football ground disasters, namely the fire at Bradford and the apparent failure of crowd control by the police at Hillsborough. In the ‘empirical’ tradition, the Bradford fire resulted in the Fire Safety and Safety of Places of Sport Act 1987; similarly immediately following the Marchioness catastrophe (Appendix) new lookout rules were proposed for river boats and, in the autumn of 1990, the transference of the railway inspectorate from the Department of Transport to the Health and Safety Executive.

The fragmentation of enforcement responsibilities which remains, even after the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, and the independence of the public services of both private control and of each other, must surely motivate against the development of a coherent national system of emergency procedures for the provision of rescue and damage control services.

Emergency procedures offshore

The problems of setting up, maintaining and putting into practice emergency procedures for the offshore oil industry on the continental shelf of the North Sea have some similarities to, and some interesting contrasts with, the problems which face onshore industries. The major differences are above all those created by operation within the marine environment which clearly demands that special attention be given to procedures for evacuation and rescue. Secondly there is a particular need to ensure damage control both for the preservation of the marine environment from pollution and for the conservation of natural resources. Further, while there is not the same problem of ensuring public safety offshore, there is, due to the prevalence of sub-contracting, a real difficulty of ensuring that safety procedures are known and understood by the whole of the largely fragmented workforce. Finally there is, as in onshore situations, a need to relate the industry's emergency procedures to the public emergency services. The practical problems are the same for operators, whether in the UK or the Norwegian sectors of the North Sea; except that the weather – always a hazard in itself – is likely to be even more treacherous at the more northerly latitudes where operations are carried out in the Norwegian sector. The interest for the lawyer lies in comparing the regulatory systems which have been set up by Norway and the UK for the resolution of what is broadly a common problem.

It has never been possible to ignore the potential for catastrophe in offshore operations as may be demonstrated by mentioning but a few of the major accidents which have occurred offshore, in the last twenty years. Incidents in which there were major losses of life, such as the capsizing of the Alexander Kielland in the North Sea (Norway, Ministry of Government and Labour 1982) and the loss of the Ocean Ranger in the Atlantic (Canada, Royal Commission 1984), have been associated with inability of the design and structure of the installations concerned to meet bad weather conditions. The Ekofisk blow-out was the consequence of defective procedures in a ‘workover’; but, fortunately, while there was considerable loss of petroleum and difficulty in capping the flow of petroleum, there was no loss of life (Norway, Ministry of Government and Labour 1978).

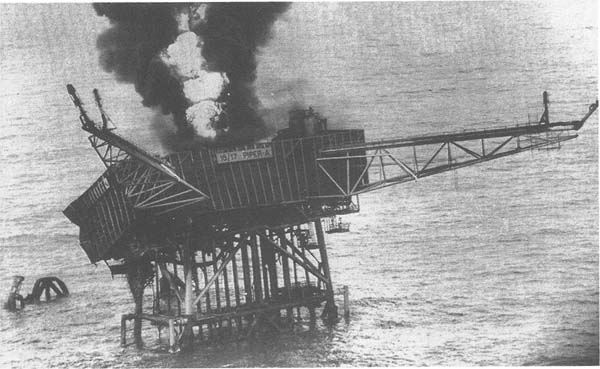

The consideration of the problem of safety offshore is, however, of particular relevance at the moment in view of the major disaster involving the Piper Alpha (Figure 7.1) installation in July 1988 on the UK sector of the shelf. Not only was this a very serious occurrence involving the loss of 167 lives, (165 of the 226 persons on board the installation and 2 rescue workers), but it occurred in good weather and was attributable to a breakdown in the safety systems offshore at Piper Alpha itself and adjacent installations. Moreover the initial problems were exacerbated by poor emergency responses on board and in the immediate vicinity of the installation. Additionally, at Piper Alpha, as at Ekofisk (see Norwegian Action Command Report 1977), difficulty in capping the flow of petroleum inevitably caused a considerable waste of natural resources: fortunately in neither case was there any long term pollution.

There have now been two official reports on the Piper Alpha Disaster: an Interim Report, which was the outcome of a provisional technical investigation and confined itself to a description of the installation, events leading up to the accident, details of the accident itself and subsequent actions (Petrie 1988). In November 1990, over two years later, the Department of Energy published a very thorough two-volume Cullen Report (Cullen 1990) which, as far as the available evidence permitted, detailed the events surrounding the catastrophe, placed these events in the context of the regulatory system and made recommendations for the future. It also made comparisons between the UK and the Norwegian regulatory systems.

In the following pages the development of the offshore regulatory systems will be outlined and some comment will be made upon the Piper Alpha disaster in the light of the Cullen Report.

Development of Offshore Regimes

National control of exploration for, and exploitation of, petroleum resources in the North Sea was facilitated by the Geneva Conventions on the Continental Shelf (1964, UKTS 39, Cmnd 2422) and on the High Seas (1963, UKTS 5, Cmnd 1929) of 1958. These Conventions encouraged the development of

regulatory jurisdiction by coastal states in terms wide enough to cater for both safety and environment protection.

The first priority of coastal states appears to have been to assert sovereignty over the mineral resources and to license offshore development while securing royalties for the state.

However Article 24 of the High Seas Convention did require every state to draw up regulations to prevent pollution from pipeline or other exploration and exploitation activities. Thus the UK Continental Shelf Act 1964 not only asserted state sovereignty in the resources in the UK sector of the North Sea continental shelf but, in section 5, also made it a criminal offence to allow oil to be discharged or to escape. Incidentally it has not proved possible to drill for and produce oil without some discharge and the regulatory systems of both the UK and Norway have had to accept this. In the UK exemptions are granted by the Department of Energy under section 23 of the Prevention of Oil Pollution Act 1971. The Department's register indicates BP was nevertheless convicted under section 3 of the Act in relation to pollution from the installation Sea Explorer. The more major problem is to try to prevent and, if that is not possible to deal with, major oil escapes in emergency situations. The continuing international concern about the potential of the industry for causing environmental pollution is evidenced by the number of international conventions on protection of the marine environment.

Relevant international conventions are the Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage 1969 ((1975) UKTS 106, Cmnd 6183); Convention Relating to Intervention on the High Seas 1969 ((1975) UKTS 77, Cmnd 6056); Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage, 1971 ((1978) UKTS 95, Cmnd 7383); and the Convention on the Prevention of Pollution from Ships 1973 (as amended) (Cmnd 5748).

However in both the Norwegian and the UK sectors the regulatory provisions relating to the prevention of the escape of oil during exploration and production (as distinct from storage and transportation) phases of the industrial activity are an integral part of emergency procedures whose primary purpose is to save life, since uncontrolled escape of oil and gas is all too likely to cause explosion and fire.

Initially both Norway and the UK relied heavily on the licensing system to control and regulate the industry. A licence is a quasi-contractual arrangement and the licensee was required to promise that he would ensure that the licensed activities were properly conducted.

The UK Regulatory style

The appropriateness of the licence for the purpose of achieving occupational health and safety was doubted in the UK after the jack up rig, the Sea Gem capsized with the loss of 13 lives (see Sea Gem Inquiry 1967). The Mineral Workings (Offshore Installations) Act 1971, therefore enabled criminal sanctions to be imposed upon operators and management if objectively determined safety standards were not observed. Thus the UK pattern of regulatory legislation was extended to the offshore workforce, but the regulations subsequently made under the Act have acknowledged the similarity between the oil and the merchant shipping industries and many of the emergency procedure standards which are applicable to installations are heavily reliant on the systems which have been developed for the merchant navy. This is particularly so in such aspects as drills and musters (The Offshore Installations (Emergency Procedures) Regulations 1976 (SI 1976 No 1542), The Offshore Installations (Fire Fighting Equipment) Regulations 1978 (SI 1978 No 611) and The Offshore Installations (Life Saving Appliances) Regulations 1977 (SI 1977 No 486). Indeed the adoption of merchant shipping standards in these matters is common to both Norway and the UK and this is hardly surprising since mobile installations are usually flag vessels; though the problem of preparation for, and evacuation into the sea is also shared by fixed platforms and therefore the regulatory provisions also extend to them. However unlike the merchant ship, the installation is required to be supported by a stand-by vessel, which must be stationed near to the installation and equipped to give aid, in the form of medical treatment, accommodation and radio communications, in emergency: in practice it may also have fire-fighting equipment (Reg. 10 of Offshore Installations (Emergency Procedures) Regulations). The evidence is that the stand-by at the Piper Alpha disaster was unable to move in close enough to use its fire-fighting equipment.

Under The Offshore Installations (Emergency Procedures) Regulations 1976, the installation has to have an emergency procedures manual (which the inspectorate may demand to see) specifying in detail the procedures to be followed in situations such as fire, explosion or blow-out. The manual must include instructions for rendering safe any work being carried out, instructions for evacuation of personnel, particulars of emergency services and names and addresses of any public or local authority to which any particular emergency is to be reported. The muster list has to name the persons responsible for shutdown procedures such as the closing of wells. These emergency provisions have to be put in the context of fairly detailed regulatory requirements for routines to ensure safety in normal working conditions in order to reduce the risk of emergency occurring – i.e. The Offshore Installations (Operational Safety, Health and Welfare) Regulations 1976 (SI 1976 No 1019).

In addition to this special offshore legislation, the onshore Health and Safety at Work Act has been extended offshore (The Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 (Application outside Great Britain) Order SI 1977 No 1232) and sections 2 and 3 are potentially of great value in ensuring that safe systems are set up and maintained, given that there is so much sub-contracting in the offshore industry; and not all offshore workers, such as catering, housekeeping, engineering maintenance and communications staff, are necessarily familiar with the risks of either the merchant shipping or the oil industries. Thus there are particular needs for co-ordination between various employers and for training of personnel. A major contribution to the extent of loss of life in the Piper Alpha disaster was that these laws had not been observed in that a very high proportion of the workforce on the installation was sub-contractor's employees who had not been familiarised with either the lay-out of the installation or the emergency procedures.

Comparisons with the Norwegian System

The regulatory system in the Norwegian sector is largely comparable to that in the UK sector in that special offshore standards, largely developed from merchant shipping practice, are married to the general onshore employment protection legislation but there are substantial differences in the enforcement of the two systems; differences which relate to allocation of responsibilities within the industry, as between the industry and the enforcement agencies and between enforcement agencies. This remains so even though the Norwegian principal legislation has been revised and re-enacted as the Petroleum Act 1985 and this revision has brought their systems somewhat closer to ours.

Firstly, in the Norwegian system, primary responsibility rests with the licensee: he rather than other persons, such as employers, installation managers or specified classes of employees, has to accept responsibility for ensuring that regulatory standards are observed. He must then, through his contractual arrangements, ensure that contractors and others in their turn observe the necessary standards. There are now criminal penalties built into the principal Act, but subordinate regulations are enforced under the general criminal code which imposes sanctions on individuals whose wilful wrongdoing or reckless behaviour causes standards to be neglected, or persons to be endangered. Secondly, in the Norwegian sector the licensee has always had to submit his systems to the inspectorate before putting them into operation: formerly the inspectorate would positively vet these systems before granting the licensee approval to start up. Since the 1985 Act much more reliance is placed upon the licensee's own ‘internal control’, but it is still necessary for the licensee to get consent before he starts an operation and this means he has, by documentation, to satisfy the inspectorate as to his standards.

This is in contrast to the UK system, where in the tradition of onshore regulatory systems, duties are imposed on the industry and the task of the inspectorate is largely to ‘spot check’. It is therefore the responsibility of the operator to both select and maintain systems and standards.

The Cullen Inquiry considered that the UK system ought to adopt something similar to the Norwegian system of internal control (which the Committee compared to our onshore Major Hazards Regulations (supra)); in their view offshore operators ought to be required to draw up, and keep under review, a ‘safety case’ identifying major hazards and stipulating measures for both accident avoidance and damage control.

Finally, in Norway the controlling enforcement agency is the leading onshore enforcement agency, namely the Ministry of Local Government and Labour, although the Petroleum Directorate (the equivalent of the UK Department of Energy) is responsible for day-to-day enforcement, acting under delegated authority. In the UK sector the onshore enforcement agency has a less significant role: enforcement offshore is through the Department of Energy, this agency having responsibility for both economic aspects of offshore development and enforcement of safety standards. The Department of Energy's inspectors are empowered to enforce both the Mineral Workings (Offshore Installations) Act 1971 and the regulations made under it, and the provisions of the Health and Safety at Work Act; the latter under an agency agreement with the Health and Safety Executive. The Health and Safety Executive does not, however, exercise any overriding authority offshore because the 1971 Act was not one of the pre-1974 safety Acts brought within the ambit of the Health and Safety Executive. In this respect the offshore situation may be contrasted with the onshore situation in offices and shops, which are subject to the Offices Shops and Railway Premises Act 1963 as well as the Health and Safety at Work Act: inspection under, and enforcement of, the former Act was and remains the task of the local authority inspectorate, and the 1974 Act is enforced by these inspectors under an agency arrangement, but the 1963 Act is now within the ambit of the Health and Safety Executive which has ultimate responsibility for the standard of enforcement in the premises concerned.

The Cullen Report recommended that the Norwegian enforcement system was preferable and in the UK sector the onshore enforcement agency (i.e. the Health and Safety Executive) should be the lead enforcement agency offshore.

Installation to Shore Rescue Provision

Some reference must also be made to the extensive voluntary emergency procedure arrangements made between the operators. The United Kingdom Offshore Operators' Association (UKOOA) publishes a Code of Practice and Plan on emergency procedures, which provide for co-operation in emergencies between operators in the five ‘Sector Clubs’ into which the UK sector of the North Sea has been divided for this purpose. UKOOA also publishes Guidance for the Preparation of Contingency Plans and Emergency Procedures to assist members to comply with the Regulations (Burgoyne Committee 1980).

In both sectors of the North Sea, emergency procedures have to make provision for rescue by and support from shore-based or other, services external to the installation. In the UK sector the industry accepts that in cases of emergency hospitalisation of workers the industry will have to arrange and pay for transportation to hospital onshore. The industry has also set up a private medical service, based onshore in Aberdeen, to provide assistance offshore. There are arrangements for liaison between, and support from, one installation to another, in a given area – i.e. the ‘Sector Clubs’. There is also, of course, the stand-by vessel which is contractually bound to serve its installation in emergency. However in the case of major emergency it may be necessary to call on public services. In the UK sector in the event of major emergency the coast guard service is recognised as the co-ordinating authority: in the case of Piper Alpha the coastguard picked up Mayday messages. When air rescue is necessary this may well involve both coastguard and the Royal Air Force while merchant navy, coastguard and Royal Navy vessels may join in sea rescue. The Times, 4 September 1989, p 2, noting ‘100 evacuated after oil rig alert’ on an Amoco rig, states that the evacuation was co-ordinated by the Aberdeen Coastguard, using helicopters from Sumburgh Coastguard and the RAF at Lossiemouth.

Significantly, emergency procedures operated relatively well in the case of Piper Alpha in respect of personnel who got away from the installation; though favourable weather no doubt helped. The only major problems related to the stand-by vessel (a converted trawler) which proved to be poorly designed and equipped for its purpose.

In the Norwegian sector, licensees are required to draw up contingency plans and obtain consent for them. It is understood that operators give considerable attention to ‘bridging documents’ in which contractors present the contingency plans for their operations, to fit into the licensee's basic plan. The Ministry of Justice has co-ordinating responsibilities where public rescue services are involved, and, when dealing with accidents which may lead to major pollution, the King may appoint a special Government Action Command Group to evaluate the measures being taken for fighting the accident, co-ordinate the work of the authorities tackling the accident and, if necessary, take over the leadership of the efforts to fight the accident.

Conclusions

The problems related to setting up and operating emergency procedures are very similar for industry whether it is operating offshore or onshore, even though offshore, public safety is not an issue but dealing with the marine environment is. In both instances industry has to draw up emergency procedures and maintain them so that they can be put into effect if the time comes when they are needed. The first priority in both instances must be to try to avoid the emergency but attention should not be focused on that to the exclusion of providing for the contingency of the emergency occurring. In both situations industry may have to rely on public services to provide rescue and damage control measures. In both situations industry must liaise with the appropriate public authorities in drawing up its plans and build into the plans provisions for calling upon public services. In the UK it is not clear that there is a sufficient mechanism for ensuring that the public services respond in a co-ordinated action, or indeed, at all, to emergency situations. It is possible that lessons could be learned from the Norwegian offshore system where the lead onshore safety enforcement agency has overall responsibility offshore and there is a greater emphasis on involvement of the inspectorate in drawing up of contingency plans. It must be admitted, however, that there does not seem to be any evidence that the current arrangements for the provision of offshore rescue services have not proved satisfactory in practice. The problems in the UK sector may possibly relate to some extent to the setting up and maintaining of safe systems within industry both offshore and onshore and to the coordination of public services onshore. The Burgoyne Committee (1980) when considering emergency procedures made no recommendations for change: however, the authors have a copy of the unpublished evidence submitted by Grampian Police and this was not so sanguine.

Recognition of the need for emergency planning against industrial accidents took a surprisingly long time to develop in the UK. The obligation imposed upon the mining industry before the First World War attracted little interest in other industries: the Robens Committee wholly ignored the subject: and indeed the Major Hazards Regulations, introduced in compliance with the EEC ‘Seveso Directive’, represent the first general decision to impose this particular obligation upon the management of potentially hazardous installations. The offshore developments discussed in this paper no doubt are more akin to shipping than to onshore experience.

It is also noticeable that most of the recent major onshore accidents have been ones, in transportation or leisure situations, in which the public have been involved. This raises further questions about whether there is a need, through the Health and Safety Executive, perhaps, to develop more clearly defined procedures for crowd control and emergency evacuation of the public.

It may be that the Norwegian concept of a public Action Command Group, operating in tandem with an industry responsible for lodging contingency plans, is one which the UK might well consider for introduction both offshore and onshore, in view of the present unease concerning command structures in putting emergency procedures into operation.

REFERENCES

Aberfan Tribunal (1967). Report of the tribunal appointed to enquire into the disaster at Aberfan on October 21st 1966. HL 316, HC 553, HMSO.

Action Command (1977). The Bravo Blow-out. (The Action Command's Report). NOU. 578, Chapter 8.

Barrett, B., Howells, R. and James, P. (1985). Employee Participation in Health and Safety: the Impact of the Legislative Provisions – First report of a survey of thirty organizations (Middlesex Polytechnic Business School).

Burgoyne Committee (1980). Report of Committee on Offshore Safety. (Cmnd 7841), HMSO. (UKOOA evidence pp 259–262).

Canada, Royal Commission on the Ocean Ranger Marine Disaster on 15th February 1982. (1984). Report of the Commission. St. John.

Cullen, The Hon. Lord (1990). The Public Inquiry into the Piper Alpha Disaster, Department of Energy, November. (Cmnd 1310), HMSO.

Hutchins, B.L. and Harrison, A. (1966). A history of factory legislation. (3rd Edition). Frank Cass and Co Ltd.

Norway, Ministry of Government and Labour (1978). Report No. 65 to the Storting (1977–78): The uncontrolled blow-out in the Ekofisk Field on 22 April 1977.

Norway, Ministry of Government and Labour (1982). Report No. 67 to the Storting (1981–82): the Alexander Kielland incident.

Petrie, J.R. (1988). Piper Alpha technical investigation interim report. Petroleum Engineering Division, Department of Energy.

Robens Committee (1972). Safety and Health at Work. Report of the Committee 1970–72. (Cmnd 5034), HMSO.

Sea Gem Inquiry (1967). Report of the Inquiry into the causes of the accident to the drilling rig Sea Gem. (Cmnd 3409), HMSO.

Cases cited

Gouriet v Union of Post Office Workers [1977] 3 WLR 300.

R v Pittwood [1902] 19 TLR 37.

R v Swan Hunter Shipbuilders Ltd [1981] 1 CR 831.

McArdle v Andmac Roofing Co [1967] 1 ALL ER 583.

Hill v Chief Constable of West Yorkshire [1987] 1 ALL ER 1173.

R v Chief Constable of Devon and Cornwall ex CEGB [1981] 3 WLR 961.

Glasbrook Bros Ltd v Glamorgan County Council and Others [1925] AC 270.

Harris v Sheffield United Football Club Ltd [1987] 3 WLR 305.

Upton-on-Severn Rural District Council v Powell [1942] 1 ALL ER 220.

Mailer v Austin Rover Group plc [1989] 2 ALL ER 1087.