SECTION I

Introduction

CHAPTER 1

The mismanagement of hazards

Introduction

Hazards are an inevitable and normal consequence of human interaction with our natural and social environments and from our development and use of technology. Such interactions and technology are pursued because they bring large benefits and opportunities to society. Sometimes, in our efforts to take full advantage of benefits and opportunities, hazards are intensified and risk is heightened. Hazard and risk are ever-present features of everyday life requiring adaptive responses from individuals and society, and in our complex society sophisticated adaptive responses are needed. If we fail to adapt sufficiently then hazards will be costly and disruptive and, when hazards are mismanaged, serious accidents and disasters occur.

The contention of this volume is that, in Britain at least, in the latter part of the twentieth century, we are failing to adapt successfully to hazards and risk posed by normal, everyday life. Disasters have been occurring too frequently and too many have lost their lives or been injured in accidents, emergencies and disasters. This problem is also present in other countries to a lesser or greater degree.

Hazards and disasters in Britain have been analysed by several authors including Whittow (1980), Perry (1981) and Cook (1989) but hitherto relatively little attention has been focused upon emergency planning and management within the context of hazard management. This volume seeks to address this limitation and presents some explanations for our current mismanagement of hazards. While the recent record of British hazard management and emergency planning is open to criticism, there are strong hopes for better planning and management in the future. This volume introduces a number of promising concepts, principles and techniques which point towards ways of enhancing the effectiveness of hazard management and emergency planning during the 1990s and beyond.

The disastrous decade

During the 1980s Britain experienced an unprecedented series of quasi-natural, technological, social and transportation incidents and disasters which were continued into 1990 (Appendix). These were more frequent and of much greater impact than expected by the public and most political policy-makers. These incidents and disasters led to widespread shock and disbelief and in their wake there was rising public and media criticism of the performance of systems for disaster prevention, and emergency planning and management. As well as increasing legal pressure on corporations, through advances in the case for corporate responsibility for much greater attention to safety, there has been mounting pressure upon central government from professional disaster and emergency planners for improvements. The accidents and disasters, and the well publicised series of inquiries which have followed them, have raised serious questions about the adequacy of hazard assessments, hazard forecasting systems, disaster warning dissemination systems, training, safety laws and procedures, inter-agency coordination, responsibility and liability for public safety and the financial capability and legal powers of the peacetime emergency planning agencies.

Thirty-six major incidents and disasters, including road, rail and air crashes, ship sinkings, terrorist bombings, fires, riots, explosions, and a mass shooting, occurred in Britain, or on sea routes to Britain, between January 1984 and December 1988 and are catalogued by Walsh (1989). In terms of loss of life the most serious of these incidents was the 1988 terrorist bombing of a Pan Am jet over Lockerbie in which 270 passengers died and 200 people were rendered homeless, the 1988 Piper Alpha oil rig explosion in the North Sea in which 165 people died, and the 1987 Zeebrugge ferry sinking in which 193 died and there were approximately 400 casualties. This catalogue excludes the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear reactor accident which led to variable radiation contamination of large areas of Britain and to widespread criticism of warnings and response from government. It also excludes the so-called ‘Great Storm’ of October 1987 in which unpredicted hurricane-force winds led to the deaths of 19 people and the then single largest-ever insurance industry payout (Handmer and Parker 1989). This spate of major incidents continued after December 1989 with the River Thames Marchioness pleasure boat sinking (56 drowned), the 1989 Hillsborough football stadium disaster in which 95 people were crushed to death, the January 1990 floods and storms in which 50 people died in predicted high winds, and the April 1990 ‘poll tax riots’ in central London in which over 150 people were injured. In recent years the most common ‘recurrent’ type of major incidents have been riots, disasters affecting football crowds, transportation disasters (especially rail crashes), fires, terrorist bombings and storms (Appendix).

Definitional issues

The definition of hazard and disaster has been the subject of much debate. ‘Hazard’ is seen as a ‘situation that in particular circumstances could lead to harm’ (Royal Society 1983, p 22). Central to this conception is the idea that hazard is an ever-present condition which periodically leads to a harmful event. Statements about the probability of occurrence of a harmful event are usually referred to as statements about ‘risk’ (Handmer and Penning-Rowsell 1990). Hewitt (1983) states that ‘hazard’ refers to the potential for damage that exists only in the presence of a vulnerable human community. This conception usefully embodies the idea that harmful events which arise in hazardous environments may be reduced by altering the vulnerability of the exposed population. Implicit in many definitions of ‘hazard’ is that the harmful event is one to which humans are exposed. However, there are also hazards to which, in particular circumstances, only flora, fauna and other elements of the natural environment may be directly exposed. For example, hazard may be posed by oil spillages which could lead to major damage to marine life.

‘Hazard management’ embraces everything from hazard evaluation and identification through to recovery from a disaster and post-event evaluation or feedback, and includes emergency planning and management and disaster management.

‘Disaster’ is often the term given to the harmful event referred to in definitions of hazard. Thus, according to Whittow (1980, p 19) whereas ‘a hazard is a perceived natural event which threatens both life and property – a disaster is the realisation of this hazard’. Whittow, whose focus is on environmental hazards, apparently excludes man-made events and those events caused by the failure of technological systems, each of which can cause disaster. Cohen and Ahearn (1980), who focus on the human victims of disasters, refer to disasters as ‘extraordinary events that cause great destruction of property and may result in death, physical injury, and human suffering’. They apparently exclude ‘environmental disasters’, such as the Exxon Valdez oil pollution accident of March 1989 which severely affected the coastal areas and marine life of Alaska.

Keller et al (1990) state that a disaster is ‘an event which afflicts a community the consequences of which are beyond the immediate financial, material or emotional resources of the community’. Disaster has also been defined as ‘usually overwhelming events and circumstances that test the

adaptational responses of community or individual beyond their capability, and lead, at least temporarily, to massive disruption of function for community or individual’ (Raphael 1986, p 5). This definition is useful because it implies that communities have differential resilience or capacity to respond to disasters.

Although this volume is concerned primarily with hazards faced by, and disasters to, human beings and communities, a preferred definition of disasters is: ‘an unusual natural or man-made event, including an event caused by failure of technological systems, which temporarily overwhelms the response capacity of human communities, groups of individuals or natural environments, and which causes massive damage, economic loss, disruption, injury and/or loss of life’. This definition encompasses medical accidents and disasters such as those which have arisen from the negative affects of whooping cough vaccine, Opren and HIV/AIDS haemophiliac cases.

Britton (1986) emphasises the importance of distinguishing between ‘accident’, ‘emergency’ and ‘disaster’. He views these as being not only quantitatively different, in involving different numbers of people and damage, but more importantly qualitively different. These differences are expanded upon by Auf der Heide (1989) (Table 1.1). From the perspective of management there are important differences between ‘accident’, ‘disaster’, ‘crisis’, ‘major incident’, and ‘emergency’ – all terms widely used in hazard management and emergency planning.

In Britain the police define a ‘major incident’ as any emergency that requires the implementation of special arrangements by one or all of the emergency services for rescue and transport of a large number of casualties, the involvement of a large number of people, the handling of a large number of enquiries from the public and news media, the large scale combined resources of the three emergency services and the mobilisation and organisation of the emergency services and supporting organisations to cater for the threat of death, serious injury or homelessness to a large number of people (Association of Chief Police Officers 1990).

An ‘accident’ is an event which is comfortably handled by local resources, but a disaster causes more disruption and, at least temporarily, exceeds the capability of local resources. In disasters the emergency and rescue services might themselves be involved as victims, whereas in accidents this is not usually so. Thus, in planning for disasters, as opposed to accidents, emergency managers must foresee the need to make arrangements for external resources to be deployed, and develop plans to overcome the disablement of key emergency services. Green and Parker (1985) distinguish between a ‘major incident’ and a ‘disaster’. Essentially, a major incident is a harmful event with little or no warning and which requires special mobilisation and organisation of the public services, whereas in a disaster it is the public who are the major actors.

Quarrentelli (1978) and others stress the social nature of hazards and disasters which they view as being essentially created (i.e. man-made), causing social disruption and necessitating social response. This theme is followed in this volume in Chapter 11 in which Kreps considers how communities perceive hazards and disasters, and also by Lewis in Chapter 13.

‘Emergency planning’ is used for that part of the hazard management process which is necessary to plan for an emergency, accident or disaster should one occur: this is discussed further in the next section. The term ‘civil protection’ is emerging both in Britain and in the European Community to describe unified civil defence and peacetime emergency planning.

Conceptualisation

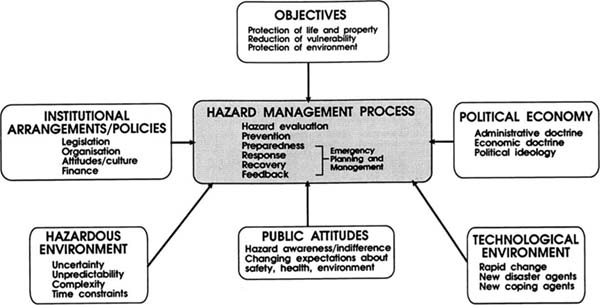

The conceptualisation in Figure 1.1 sets out some of the most pervasive groups of influences acting upon the hazard management process. The objectives of hazard management may be considered to be the protection of life, property, the community and the environment, but reducing the vulnerability of

individuals and the community to disaster is also considered by many as central. Green expands upon such objectives in Chapter 12 and Lewis emphasises the importance of reducing individual and community vulnerability to hazards in Chapter 13.

The process of hazard management comprises a series of well-known stages which begins with hazard evaluation (Figure 1.1). The second stage involves the evaluation, selection and implementation of hazard reduction and disaster prevention measures, and the establishment of enforcement procedures where these are important to prevention. It is this stage which effectively links ‘hazard management’ to ‘emergency planning and management’ – the subsequent stages of the process.

Within emergency planning and management there are three principal stages: ‘preparedness’, ‘response’ and ‘recovery’ (Raphael 1986, Comfort 1988) (Figure 1.1). ‘Preparedness’ involves foreseeing potentially harmful events by providing contingency plans; training emergency planners and managers; and educating the public so that they may reduce their vulnerability. ‘Preparedness’ also encompasses the development of warning systems and their operation. The mobilisation of emergency personnel and resources; search and rescue; evacuation; and the provision of emergency shelter and emergency feeding arrangements: these are all examples of activities undertaken in the ‘response’ phase (Drabek 1987, p 24). The ‘recovery’ stage involves cleaning-up operations; repair and reconstruction; liability assessment; victim counselling and other forms of rehabilitation planning and action.

The final stage in the hazard management process is the ‘feedback stage’. Preventative measures which may involve structural engineering projects, such as flood protection schemes or fire-proofed structures, require post-project appraisal to evaluate their performance. Similarly, it is important for search and rescue teams and others involved in emergency to evaluate their performance after the event.

Hazard management takes place within an environment of uncertainty, unpredictability and complexity. This environment presents time constraints, sometimes severe ones, which limit what can be achieved (Figure 1.1). Public attitudes towards hazards and risks, including the awareness of individuals of the hazards they face, is an important problem. This is explored further by Kreps in Chapter 11 where he contends that public apathy and indifference is a major hindrance to hazard management.

The hazard management process is open to three other principal sets of influences: institutional arrangements and policies, the political economy and the technological environment. These influences exert two types of forces upon the process of hazard management: positive forces strengthening the process and thereby making it effective; and negative forces which either weaken the effectiveness of the management process or increase society's vulnerability to hazards and disasters.

Institutional arrangements, which comprise legislation, organisational arrangements, attitudes and sub-cultures and financial arrangements, provide the ‘infrastructure’ behind the hazard and disaster management process. They both reflect and generate policies. These all determine how agencies respond to particular tasks. Financial arrangements are of central significance and to an important extent determine the resources which can be devoted to hazard management.

Institutions and policies are designed to make possible effective hazard management, but institutional inadequacies impede the process and may act in a negative or disintegrative manner. For example, in Chapter 9 Hood and Jackson explore the possible part played by government in contributing to or causing disasters. Strong organisational sub-cultures (Turner 1978), which may be a positive force for discipline within an organisation, may give rise to inter-agency rivalry leading to poor communications when effective communication is vital. Adequate finance enables hazard management, but where financial arrangements are inadequate, necessary adaptive responses may be constrained.

The political economy is an indirect but totally pervasive influence upon hazard management. The political economy contains within it both the preconditions for accident and disaster on the one hand, and on the other the potential for improved disaster prevention and management. Prevailing administrative and economic doctrines, political ideologies and political priorities all set the conditions either for improved disaster prevention and management or for deteriorating safety and increased hazardousness. Similarly, the impact of the technological environment is double-edged. Technological advance opens up possible new avenues and opportunities for disaster prevention and emergency response, for example as demonstrated by Murray and Wiseman in Chapter 15 in relation to the power of electronic databases for storing and managing hazard information. But there is also no doubting that new technologies also increase society's vulnerability to disaster in a wide variety of ways.

Overall, the principal influences on hazard management, portrayed in Figure 1.1, may be perceived of as preconditions and potentials which are prevailing and countervailing forces, conflicting with one another rather than providing mutual reinforcement. It is this fundamental problem which leads to the mismanagement of hazards. This theme is expanded upon by various authors in Section II, and by Pidgeon et al in Chapter 17 who argue the importance of ‘safety culture’.

Institutional arrangements for civil protection in Britain

The legislative and organisational arrangements for disaster management in Britain, including emergency planning and management, are extraordinarily

|

* In Scotland the equivalent legislation is The Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973.

** In Scotland the equivalent legislation is the Civil Defence (GLAS) (Scotland) Regulations 1983.

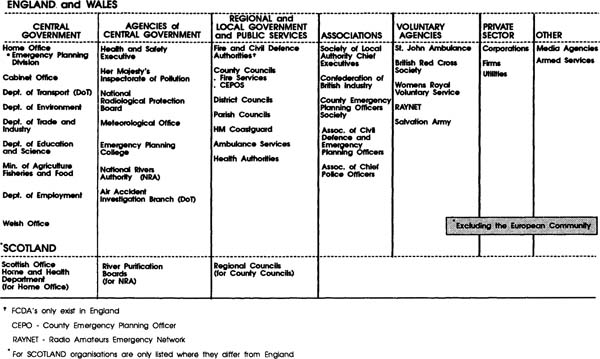

complex. Responsibilities for health, safety, disaster prevention and environmental protection cut laterally across all aspects of society, life and work; involve almost all organisations; involve the public and private sector; and should be relevant at all levels within organisational hierarchies. Any attempt to represent these arrangements in diagrammatic form is problematic because of the complexity of society and government. Nevertheless, it is possible to identify key statutes; principal or lead organisations; important distinctions which have been made within disaster management; and certain aspects of Britain's disaster management culture.

Legislative authority

Selected legislation relating to the prevention of disasters and the control and coordination of emergency services and others in the case of an accident or disaster is given in Table 1.2. This legislation is complemented by a host of other legislation relating to specific hazards and dangers, and is increasingly underpinned, and in some cases, led by European directives or laws. The legislation relating specifically to ‘civil protection’ or emergency planning and management is of two types – that relating to civil defence or wartime emergency planning, and that relating to peacetime emergency planning. This volume focuses principally upon planning for and management of peacetime emergencies and Table 1.2 only lists the principal civil defence legislation.

In English law there is a distinction between permissive powers and mandatory or obligatory duties. This is most important in interpreting the responsibilities of local authorities and other organisations for hazard management.

Apart from the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974 and the CIMAH Regulations of 1984 (Table 1.2), mandatory duties currently relate mainly to civil defence or wartime emergency planning, whereas peacetime emergency planning powers exist rather than duties. The Civil Defence Act 1948 gives local authorities mandatory duties for ‘defence against any form of hostile attack by a foreign power’, but this specifically excludes hostile attack by terrorists and peacetime emergencies. The Civil Defence Regulations of 1983 established Planned Programme Implementation (PPI) timetables for the implementation of civil defence wartime emergency planning which local authorities were obliged to adopt, following the earlier period of disintegration of civil defence planning in many parts of Britain.

Under the Local Government Act 1972, Section 138, County and District Councils in England and Wales have powers in situations where an emergency or disaster involving destruction of, or danger to, life and property occurs or is imminent, or where there is reasonable ground for expecting such an event to occur. In such circumstances councils may incur expenditure in order to avert, alleviate or eradicate the effects or potential effects of the event and they may make grants or loans to these ends.

The Local Government and Housing Act 1989 amended Section 138 and extended these powers (not duties) where it is considered appropriate to undertake contingency planning to deal with a possible emergency or disaster which might involve destruction of, or danger to, life and property, and might affect the whole or part of a council's area (Sibson 1990). Therefore, it is important to recognise that currently in England and Wales, although councils often feel a moral obligation, they are not obliged by the law to exercise their peacetime emergency planning and management powers. The extent to which councils can engage fully in emergency planning and management is limited by the law and by financial practicalities that are associated with permissive powers rather than legal duties.

While Section 138 of the Local Government Act 1972 gave powers to councils to incur expenditure to prepare emergency plans, it did not give powers to Fire and Civil Defence Authorities (FCDAs) which also exist in metropolitan areas only in England. This position was amended under the Local Government and Housing Act 1989, Clause 156, and from 1 April 1990 the FCDAs were given powers, with the approval of the Secretary of State at the Home Office, to coordinate the emergency plans of principal authorities. Nevertheless the role of the FCDAs remains limited since they do not have powers to prepare a coordinating plan as such.

In Chapter 7 Barrett and Howells examine the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, the purpose of which is to promote the health, safety and welfare of people in the workplace and the control of dangerous substances and certain emissions to the atmosphere. This Act is complemented in a complex way by other legislation relating to transportation, such as the Road Traffic Acts, the Civil Aviation Acts and the Merchant Shipping Acts.

The CIMAH Regulations of 1984 (Table 1.2) are the British response to the European Community Directive on Major Accident Hazards of Certain Industrial Activities (82/501/EEC) 1982, widely known as the ‘Seveso’ Directive (European Community 1982). The 1982 Directive followed the accidental release of dioxins as part of a by-product at an industrial plant at Seveso during 1976 which caused widespread contamination and health damage. The British response to the Directive followed the 1974 Flixborough chemical plant disaster, in which 28 workers died and 1,800 houses off-site suffered damage, following a massive explosion in the process plant. The British precursor to the CIMAH Regulations was the 1982 Notification of Installations Handling Hazardous Substances Regulations. Through the CIMAH Regulations emergency planning both on- and off-site became part of disaster management in Britain.

The Civil Protection in Peacetime Act 1986 was an attempt by central government to strengthen the peacetime emergency planning powers of local authorities. It permits local authorities to utilise resources provided for war or ‘civil defence’ planning to meet the effects of peacetime emergencies and disasters unconnected with any form of hostile attack by a foreign power. Ultimately the effect of this Act was negligible because it failed to give local authorities a statutory duty for peacetime emergency planning.

The legislation in Table 1.2 is supported by a wide range of additional legislation, including the police Acts, and central government's and professional bodies' guidance applicable to particular hazards and safety risks. For example, specific legislative authority is laid down for fire hazards, safety at football grounds (e.g. Fire Safety and Safety of Places of Sport Act 1987), product safety and consumer protection (e.g. Consumer Protection Act 1987) (Abbott 1987), food protection (e.g. Food and Environment Protection Act 1985), and dam safety (e.g. Reservoirs Act 1975). Central government gives further direction through guidance notes, such as the Home Office Circular SS22-24 1985 entitled ‘Emergency Planning Guidance to Local Authorities’ (EPGLA) which described the roles of the principal emergency services, local health authorities, voluntary associations and the military (Home Office 1985). However, of the 26 sections in the 1985 Home Office Guidance Notes, 21 sections are devoted to civil defence or wartime planning including response to conventional and nuclear attack. The arrangements for military assistance to the civil community (the MACC scheme) are published by the Ministry of Defence (1978).

Organisational arrangements

All central government departments play a role in overseeing legislation relating to one or more aspects of safety, hazard reduction and emergency planning and management. The current approach is that the central government department with the most involvement in an accident or disaster is the ‘lead department’. Nevertheless, as explained further by Handmer and Parker in Chapter 2, the Home Office, supported by the Cabinet Office, is emerging as the principal central government ministry with oversight for emergency planning and management in England (Figure 1.2), with the Welsh Office in Wales and the Scottish Office (Home and Health Department) in Scotland having similar roles. Currently the ‘lead department’ in England for most severe weather emergencies, for satellites falling to earth and sports ground incidents is the Home Office. The ‘lead department’ responsibilities are under review and subject to further guidance notes being prepared by the Civil Emergencies Adviser to the Home Secretary.

A number of central government agencies including the Health and Safety Executive (HSE), Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Pollution (HMIP), the National Radiological Protection Board (NRPB) and the Meteorological Office (MO) have a specially defined role in hazard management and emergency planning and management. The HSE is responsible for enforcing legislation concerned with the dangers arising at work and from work activities. The HSE is involved in the identification of hazardous installations, cooperation with local planning authorities on land use planning issues and enforcing the CIMAH Regulations. HMIP has responsibilities for various aspects of pollution control including the national plan for overseas nuclear accidents whose radiation may affect Britain. The NRPB is the standard-setting agency for radiological emissions. The MO is an executive agency which provides weather forecasting services to those paying for the service including the taxpayer. The MO therefore has a central role in initiating warnings of severe weather likely to lead to accident or disaster, such as floods or strong winds (Handmer and Parker 1989).

Most central government departments and many organisations are also involved in disaster prevention, though not all are listed in Figure 1.2. For example, in the flood hazard reduction field ‘flood defence’ powers, including flood warning systems, currently lie principally with the National Rivers Authority (NRA). Under the Water Act 1989 the NRA is overseen by the Department of the Environment, and to a lesser extent by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. The NRA has permissive powers for constructing flood alleviation projects. The NRA also responds to emergencies, such as a flood disaster caused the breach of flood embankments, by undertaking ‘flood fighting’, emergency repair and rehabilitation works (Parker et al 1987). Similar ‘field specific’ arrangements exist for disaster prevention for dam safety, fire safety and other fields including offshore safety for the oil industry (see Barrett and Ho wells, Chapter 7).

In emergency planning and management the principal sub-national lead organisations are the county and district councils, and in Scotland the Regional Councils have a similar role. There are also Fire and Civil Defence Authorities in England for metropolitan areas. All are overseen by the Home Office and other central government departments (Figure 1.2). In some instances in England and Wales the county fire services department is the lead emergency planning and management agency in creating a county civil emergency plan

and in coordinating other county services. These services include the county emergency planning team, social services departments and external organisations such as the voluntary agencies (see Moore, Chapter 5), but this is not the case in all counties where the emergency planning team may lead. Other organisations, including the police authorities and the health service, also have a central role in planning and responding to emergencies. Within metropolitan areas the borough councils have the responsibilities for civil defence, while the Fire and Civil Defence Authorities may attempt to coordinate the peacetime emergency planning of these borough councils. Emergency planning and management are also undertaken by the district councils in England and Wales which are overseen by county councils. In some cases parish councils have developed community level plans.

The emergency planning and management system is supported by an array of voluntary agencies (Figure 1.2). The role of the St. John Ambulance Brigade is expanded upon in Chapter 6 by Fenton. Britain's large voluntary emergency service sector includes the 10,000 strong Royal Observer Corps which, under wartime emergency planning the government maintains would be employed to gather information on nuclear weapons and to monitor fall-out levels following nuclear attack.

Training for civil emergencies is handled in a number of colleges including the Police Staff College and the Fire Service College. From 1989 the Civil Defence College at Easingwold in Yorkshire became the Emergency Planning College marking the extension of its remit from war to civil emergency planning.

The hazard management culture

Research on organisations and disasters has revealed that organisations often develop distinctive sub-cultures which strongly influence how they respond to risks and hazards. Ultimately, these sub-cultures determine the ability of organisations to respond successfully to events which may develop into emergencies or disasters (Turner 1978). For example, Turner observed that it is common for organisations to breed a sub-culture of allegiance among employees, and for certain ways of thinking and certain sets of priorities to become accepted at the expense of others. ‘Rigidities in perception’ may contribute to disasters or reduce an organisation's hazard response potential.

It is possible to identify in Britain certain attitudes, beliefs, traditions and accepted norms which comprise the culture of hazard management agencies and many of those who work within them, including central government departments. This is certainly not to suggest that everyone within the field of hazard management in Britain thinks alike, or that change does not take place, but the contention is that a dominant culture is identifiable. This is expanded upon in Section II and is commented upon in the final Chapter. In Chapter 17 Pidgeon et al develop the analysis further to identify the elements which they believe should exist within a ‘safety culture’.

Financial arrangements

The financial arrangements for hazard management in Britain are as diffuse as the number of organisations, and thus organisational budgets, involved in hazard management. In some cases central government provides a subsidy to encourage hazard management. For example, government grant-aid subsidy is available to the National Rivers Authority and to local authorities for flood protection and sea defence projects which are demonstrated to be economically efficient.

The civil defence component of local authority emergency planning is grant-aided by central government through the Home Office civil defence grant and through a similar grant from the Scottish Office in Scotland. Thus, the salaries of county emergency planning officers and some members of their support teams, and emergency planners in Fire and Civil Defence Authorities are funded in this way. The total grant-aided civil defence expenditure by local authorities was approximately £23 million in 1988–89. However, in some cases local authority emergency planners are funded directly by county and district councils.

There is no direct central government grant-aid for civil, peacetime emergency planning in Britain – a source of considerable concern to emergency planning officers, their professional associations and others. Local authorities vary in their enthusiasm for emergency planning but many add funds to the civil defence grant in order to make sure that peacetime emergency planning takes place alongside civil defence planning. In special cases, under the Bellwin Scheme, grant at a rate of 95% is available from central government to cover local authority expenditure on emergency work. The normal period for financial assistance under the Bellwin Scheme is 3 months but it may be extended beyond this in exceptional circumstances. In severe cases financial assistance may also be available to local authorities from the European Community.

The political economy and technology context

The 1980s were marked by a number of clearly discernible trends in administrative and economic thinking often originating with government. These trends coupled with fast technological change may have combined to make society more vulnerable to disasters than previously. In Chapter 9 Hood and Jackson argue that a new set of administrative doctrines referred to as the ‘new public management’ began to prevail in Britain and elsewhere during the 1980s. The components of this doctrine include the break up of administrative units into separately-managed entities which are corporatised and privatised, and which transact with each other on a user-pays basis. There is also an emphasis upon cost-cutting, deregulation, commercial secrecy and adherence to performance targets. They argue that the new public management, with its promulgation of discrete organisations, is more prone to engendering socially-created disasters than the traditional approaches to government in which a ‘systems’ view of organisation and a public service ethic prevailed. Paradoxically deregulation has become a popular process during a period in which, through the occurrence of disasters, there has been ample demonstration of the need for more tightly regulated safety.

This set of ideas connects with the emergence in Britain of an ‘enterprise culture’ which has been associated with the creation and opening of markets, increased competitiveness, and pressure to change and to adopt new technologies. Under the contrasting ‘welfare state’ philosophy, which withered in Britain during the 1970s and 1980s, there was a strong ownership and regulatory role for government but in an ‘enterprise culture’ the opposite has prevailed (Handmer and Penning-Rowsell 1990). The government's approach to Britain's declining economic fortunes has been to turn to unfettered market forces, deregulation and privatisation. Within an ‘enterprise culture’ in which the emphasis is upon survival and output, safety matters become a second priority.

Hazard managers are increasingly seeking ways of employing modern technology to reduce hazards, to prevent disasters and to respond to accidents and disasters when they do occur. The employment of electronic databases in responding to chemical poisoning incidents, explained by Murray and Wiseman in Chapter 15, is one example. However, the link between rapid technological change and the occurrence of disasters appears to be an important one, though it is sometimes difficult to trace. New technology is adding to the list of disaster agents on a daily basis through the introduction and transport of hazardous chemicals, dependence upon computers and the proliferation of high-rise buildings prone to fire (Auf der Heide 1989). As systems become more complex, and as reliance grows upon such systems, so the potential for catastrophe appears to increase.

The evidence of recent post-disaster inquiries and investigations also suggests that Britain's economic decline during the 1970s, coupled with downwards pressure on public expenditure, may have contributed to disasters. Horlick-Jones (1990) points out that nowhere is this more apparent than in the provision of public services either by state-run transport systems responsible for the aging King's Cross escalator (Department of Transport 1988), or the squalor of the private football stadia which was condemned in Lord Justice Taylor's report on Hillsborough (Home Office 1990). Dereliction, delayed repair and maintenance and reduction of cleaning operations all appear to contribute to increased proneness to disaster.

Summary

In Britain a series of pervasive influences appears to have combined to reduce society's ability to manage hazards effectively, at least in the recent past. We appear to be failing to adapt sufficiently to hazards and our ‘mismanagement’ of hazards has led to a series of accidents and disasters. The pervasive influences are identified in Figure 1.1, introduced above and analysed further in the remainder of the volume. In particular institutional arrangements and policies, including certain attitudes and aspects of our culture, appear to be inadequately attuned to the needs of effective hazard management: change is needed but is often too slow. There are arguments that administrative, political and economic policies are contributing in important ways to ineffective hazard management.

Organisation of the volume

The conceptualisation and the background to hazard management in Britain discussed above sets the scene for the chapters which follow, though not all the authors work within this same conceptual frame. Section II provides further explanation of the government's most recent thinking on emergency planning and management together with a series of chapters which are critical of current thinking on, and arrangements for, hazard management in Britain. These chapters focus most closely upon emergency planning and management rather than upon the full process of hazard management as conceptualised above. Section III comprises a number of chapters which contribute possible explanations for the current problems which we face in managing hazards and disasters. These chapters include discussions of legal frameworks, social science perspectives and the new field of corporate responsibility. There is also a comparative analysis of football ground disasters in Britain and Belgium. Section IV introduces a number of concepts, ideas and examples drawn from British and international experience, which may be used to enhance the effectiveness of emergency planning for disasters in the future. Section V comments upon the current state of hazard management in Britain, including emergency planning and management, and points the way towards greater effectiveness.

To help integrate the volume an attempt is made, at the end of each section, to synthesise the main points arising from the chapters.

REFERENCES

Abbott, H. (1987). Safer by design: the management of product design risks under strict liability. Design Council, London.

Association of Chief Police Officers (1990). Police Emergency Procedures Manual, ACPO Special Purposes Committee Working Party, London.

Auf der Heide, E. (1989). Disaster response: principles of preparation and coordination, C.V. Mosby, Baltimore.

Britton, N.R. (1986). Developing an understanding of disaster. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Sociology, Vol 22, 254–71.

Cohen, R.E. and Ahearn, F.L. (1980). Handbook for mental health care of disaster victims, Johns Hopkins, Baltimore.

Comfort, L.K. (Ed.) (1988). Managing disaster: strategies and policy perspectives, Duke University Press, London.

Cook, J. (1989). An accident waiting to happen, Unwin, London.

Department of Transport (1988). Investigation into the Kings Cross Underground Fire (The Fennell Inquiry), HMSO, London.

Drabek, T.E. (1987). The Professional Emergency Manager: Structures and Strategies for Success, Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado, Boulder.

European Community (1982). Council Directive of 24 June 1982 on the major accident hazards of certain industrial activities (82/501/EEC), Brussels.

Green, C.H. and Parker, D.J. (1985). Civil disaster management: an academic perspective, Paper presented at the Civil Defence College, Easingwold, Yorkshire.

Handmer, J.W. and Parker, D.J. (1989). British storm-warning analysis: are customer needs being satisfied? Weather, Vol 44, No 5, 210–14.

Handmer, J.W. and Penning-Rowsell, E.C. (Eds) (1990). Hazards and the Communication of Risk, Gower Technical Press, Aldershot.

Hewitt, K. (Ed.) (1983). Interpretations of Calamity, Allen and Unwin, London.

Home Office (1985). Emergency Planning Guidance to Local Authorities, (EPGLA) SS22–24, London.

Home Office (1989). Review of Arrangements for Dealing with Civil Emergencies in the UK, Home Office, London.

Home Office (1990). The Hillsborough Stadium Disaster 15 April 1989, (The Taylor Inquiry), Final Report, Cmnd 962, HMSO, London.

Horlick-Jones, T. (1990). Disaster – Acts of God? in 2nd Disaster Prevention and Limitation Conference: Emergency Planning in the 1990s, 11–12 September, University of Bradford, Bradford.

Keller, A.Z., Wilson, H. and Kara-Zaitri, C. (1990). The Bradford Disaster Scale, Disaster Management, Vol 2, Issue 4, 207–213.

Ministry of Defence (1978). Military Aid to the Civil Community: A Pamphlet for the Guidance of Civil Authorities and Organisations, 2nd Edition, HMSO, London.

Moore, G. (1990). Evaluating Emergency Plans, in 2nd Disaster Prevention and Limitation Conference: Emergency Planning in the 1990s, 11–12 September, University of Bradford, Bradford.

Parker, D.J., Green, C.H. and Thompson, P.M. (1987). Urban Flood Protection Benefits: A Project Appraisal Guide, Gower Technical Press, Aldershot.

Perry, A.H. (1981). Environmental Hazards in the British Isles, George Allen and Unwin, London.

Quarrentelli, E.L. (1978). Disasters, theory and research, Sage, Beverely Hills, California.

Raphael, B. (1986) When disaster strikes: a handbook for the caring professions, Hutchinson, London.

Royal Society (1983). Risk Assessment: Report of a Royal Society Study Group. Royal Society, London.

Sibson, S. (1990). Local authority: a planned response to major incidents, in Proceedings of 2nd Disaster Prevention and Limitation Conference: Emergency Planning in the 1990s, 11–12 September 1990, University of Bradford, Bradford.

Turner, B. (1978). Man-made disasters, Wykeham, London.

Walsh, M. (1989). Disasters, Current Planning and Recent Practice, Edward Arnold, London.

Whittow, J. (1980). Disasters: the anatomy of environmental hazards, Pelican, London.