14

CHAPTER 14 RESILIENCE

“Our greatest glory is not in never falling, but in rising every time we fall.”

Confucius1

Resilience is a common ingredient in heroes of myth and legend, a personal quality that is aspired to by many of us and sought after in leaders. The popular view of resilience (and the everyday definition) is about bouncing back, springing back into shape after pressure has been applied, elasticity, recovering quickly from difficulties, toughness.2 But the real human experience of resilience is defined a bit differently: “A resilient response to adversity engages the whole person, not just aspects of the person in order to face, endure, overcome and possibly be transformed”:3 coming back rather than bouncing back4 and returning to a different place (transformed), with new insights and new awareness. So not quite the same as you were before.

There are countless modern examples of incredible resilience where individuals have faced adverse, potentially insurmountable challenges, and have come through transformed (often both physically and mentally). One example is Italian ex-Formula 1 driver Alex Zanardi5, who lost both legs following a crash in 2001 and won gold in the cycling event at the London 2012 Paralympics.

A second example is that of Michael Watson6, a former champion boxer who suffered considerable brain damage. He was told he would never walk again. He refused to accept this prognosis and taught himself to walk. Michael successfully completed the 2009 London Marathon over a six-day period – his determination and achievement was amazing to witness.

From more of a business perspective, there are some famously wellknown resilient figures, and some less well known:

• Walt Disney7 was turned down over 300 times before he secured financing for his dream of creating “The Happiest Place on Earth”. Today, millions of people have shared in “the joy of Disney”.

• Legend has it that Colonel Sanders8 was refused 1009 times across America over a two-year period before he heard a “yes”. He was over 65 years old at the time, determined to franchise his chicken recipe. KFC is now one of the largest food franchises in the world.

• Jean-Dominique, the editor of the French fashion magazine, ELLE, had a massive stroke that left him completely immobile except for the movement of his left eye, but he devised a means to communicate through blinking and used this method to pen his memoir.9

• Richard Cartwright10, a Big Issue seller in Newcastle with a love of reading, used his profits to buy books, sourced from local charity shops and library sales. Now his company has over 140,000 titles, with 27,000 listed online, employing four local residents.

These stories provide a flavour of what might be seen as resilience. Michael Neenan11, a seasoned therapist, coach and author, describes resilience as a process of self-righting and growth – and a resilient person as someone who is strong and capable and able to be vulnerable.

Resilience is something you can develop, individually and across an organization. While developing personal resilience is down to individuals, mobilizing individual inner resources can enable groups and whole communities of individuals to tolerate, learn from and grow through adverse events.

It’s easy to see the need for resilience in some roles – those that deal with life, death and “emergency” on a daily basis (medical staff, military service personnel, or emergency response employees).

Other roles, those dealing with emotional situations and circumstances that might be less dramatic, but still highly impactful, also require resilience – front-line employees in demanding customer environments or even call centres where the main purpose is to deal with customers who have complaints.

And less obvious still, personal resilience is a particular necessity where you are more isolated. For example, it may be understandable to think of running a business or corporate profit centre as a privilege, an exciting opportunity to demonstrate performance and success and likely to be well rewarded. But the opportunity is often coupled with the frequent absence of formal support, and a strong link is drawn between the person heading the business and business results. Success and failure are highly visible. Isolation is something felt and experienced by those leading organizations and resilience is a core skill in such roles.

Resilience is rapidly becoming an essential business skill for all. Think of the constantly changing context that we live and work in: an overcrowded, busy, ambiguous environment where there are few ideas that are not questioned; where there are more possibilities than limitations; where success is seen as something everyone can easily attain; where social patterns and extended support networks have disappeared or are diminished. All these factors contribute to greater isolation and chaos so it is hardly surprising that growing your resilience skills is increasingly important.

For organizations, the business and social changes described are set in the context of a challenging global economic environment, leading to pressure to do more with less. Those who have jobs are often stretched significantly, while those made redundant find it increasingly harder to find equivalent employment. People and organizations find themselves facing uncomfortable situations more regularly or even a whole mindset focused on survival rather than performing to their best.

Resilience for organizations points to their capacity to learn, anticipate, respond flexibly to events and to recover. Developing a resilient organization is about making second nature the capability to adapt and find a way through, often using different thinking and approaches.

Just as individual resilience supports the development of organizational resilience, no organization is an island. The resilience of an organization is dependent on the resilience of other organizations within its network (suppliers and customers). The resilience of an organization supports the resilience of a sector, the individuals and communities that depend on the organization, and the geography in which it exists.

WHAT DOES RESILIENCE DO FOR YOU?

“Inner resilience is the secret to outer results in this world”

Tom Morris12

For individuals, increasing your ability to face, endure, grow and learn through adverse events enables you to experience a different quality of life regardless of your circumstances or context. Perhaps it is possible to experience enduring personal happiness through greater resilience – resilience is seen as the bedrock of positive mental health.13 Resilience is a factor in longevity and well-being. It provides you with a rooted flexibility rather than being blown about like a leaf with every shifting breeze.

In terms of the day-to-day impact at an individual level, greater mental resilience generally means you are likely to be:

• more open to people, less defensive and closed

• calmer, experiencing a lower level of stress or anxiety

• able to move forward more easily, allowing things to pass, rather than getting stuck in what has just happened

• more able to make realistic decisions (based on what is happening now, what you are doing, what others are dong) rather than being caught up in limiting ideas about what “should” happen, what others “should” be doing, or what you “ought to”, or “have to” do

• better able to openly ask for what you want and need

• more consistent and less emotionally “hijacked”

• seen as approachable and liked by others – you are less likely to upset others as a result of a fiery temper and irritability

• more adult in your approach, less demanding through either childlike sulkiness or an overbearing parental style.

Having little or no resilience, on the other hand, increases the impact of everyday stressors, and increases feelings of anxiety and depression.

The impact of stress at a macroeconomic level is huge, with the World Health Organization forecasting that depression will be the second leading contributor to the global burden of disease by 2020.14 In the UK, the economic and social costs of mental health problems in 2003/04 were estimated at £98 billion; globally, the cost is estimated at 3-4% of each country’s GDP.15

In terms of organizations: in the UK, stress, anxiety and depression accounted for 56 million working days lost in the UK in 2004,16 with each case of stress-related ill health leading to an average of 31 working days lost a year.17 This picture is replicated in other countries: for example, in the United States, job stress is estimated to cost US industry more than $300 billion a year in absenteeism, turnover, diminished productivity and medical, legal and insurance costs.18

Throw into the mix the idea that most organizations face a shortfall in resources from people who are present at work, but not performing at their best due to events (at home or at work) that distract their focus, and you can clearly see the compelling business case for building resilience.

BUILDING RESILIENCE

Getting started – paying attention to your inner world

“What lies behind you and what lies in front of you pales in comparison to what lies inside of you.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson19

As the Stoic philosopher and Roman slave, Epictetus, pointed out: “People are not disturbed by events, but by the view they take of them”. This doesn’t mean that bad things don’t happen. It does mean that we can view the same event from very different perspectives. And it is how we think about things that ultimately means we either get past events or we get “stuck” in an event.

Take the story of Alex Zanardi, the ex-Formula 1 Driver: he could have chosen to be defeated by the loss of his legs – he could have, understandably, chosen to see himself as an invalid who needed to be looked after for the rest of his life. But he chose a different path and the results speak for themselves.

Srikumar Rao,20 speaking at Google, brings our attention to our inner stories, our inner stream of consciousness. There is a constant inner voice commenting on the experiences we are having, the people we are near, the people we are thinking about, what we have just said or thought. We ignore this stream of consciousness at our peril as our beliefs, assumptions, judgements and biases all show up in this inner dialogue and the dialogue can be helpful, helping us move forward, onto the next track, or keep us stuck like a scratch on a CD (or vinyl record!), forever repeating phrases that hold us in a particular place – keeping us angry, keeping us fearful, keeping us playing small.

These attitudes and beliefs, these inner stories that you hold, have the biggest effect on your resilience.21 Your thoughts and beliefs are a key driver in how you feel and behave.

Imagine a rather innocuous situation with someone at work; let’s call him Joe. Every time you make a suggestion to change something to Joe, you get a lengthy justification of why things are as they are and why something can’t be done. If you give Joe feedback on even the smallest thing, there is a strong defence and nothing seems to be taken on board. The impact? Eventually, you might give up trying to collaborate, share your ideas or give feedback.

What might be going on for Joe? Joe may believe any number of things about himself or others. He may hold a view that he’s really a phoney and it’s only a matter of time before others find him out. He can’t easily take on ideas because he believes “if I was any good, I’d have thought of that idea myself”. He is closed to feedback because he thinks “I should be perfect and not being perfect means I’ll get found out to be a phoney.” It’s these pervasive, unrealistic and irrational beliefs that close Joe down, and lead to the responses you experience as his colleague.

What impact would it have if Joe was able to reframe his beliefs about himself, perhaps believing he was “good enough” although he could learn from his colleagues, perhaps accepting that striving for perfection means things don’t get done, so perhaps going for 80% before sharing with others is the target?

The impact of this “reframe” goes further than Joe. It impacts on his day-to-day interactions with colleagues and the whole organizational system around him.

Does Joe sound familiar? Maybe not the specific words, but this hidden inner world holds all sorts of fears that we’re worried about being exposed – perhaps you really don’t know what you’re doing, perhaps you’re not intelligent enough…

Actually, the only one who’s thinking these thoughts is you and the more you think like this, the more stress you will experience, the fewer resources you will have at your fingertips and the less resilient you will be. The more stress you experience, the greater the volume of the critical voices.

If, instead, you can harness a positive inner world that resources you – if you can shine instead of playing small – imagine what you might achieve.

THE POWER OF YOUR INNER WORLD

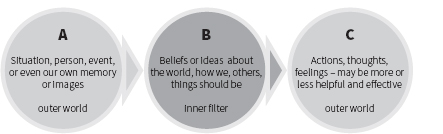

Neenan (and others) talk about the A – B – C of understanding what we do and why we do it (see diagram below).

Our inner beliefs and ideas about the world are a little bit like a hall of mirrors. The event is distorted as it’s reflected through our internal belief filters, and our responses to an event depend on how things have been distorted.

When we get angry, upset or confused, our choices of how to act are limited.

When have helpful beliefs, appreciate our resources and resourcefulness, then we have much more choice about how to behave and more resources to draw from.

Building individual resilience comes through positive emotions and optimism, humour, flexibility of thinking, reframing events, acceptance, altruism, social support, coping style, and exercise, and other factors.22

Most of the time, we are unaware of our thinking. Instead we assume we are rational human beings, responding as anyone else would to a particular situation. We’re completely oblivious to the distortions we have made to a situation – unaware of the unique hall of mirrors that we have filtered our experiences through. That is why Srikumar Rao is right when he says we ignore our stream of consciousness at our peril.

The good thing is that our beliefs and ideas about the world are learned through experience, and we can change our ideas as we become aware of them and try a different approach. It’s not always that easy though, as we’ve held onto these ideas sometimes all or most of our adult lives. Freeing yourself up from unhelpful and limiting ideas about yourself and others can be life-changing.

“It is not the mountain we conquer but ourselves.”

Sir Edmund Hillary23

Greater awareness of your inner world leads to the possibility of new thinking, leading to new actions, beliefs and feelings.

In organizations, the pattern is no different; the ABC model can be applied.

Let’s imagine a particular organization which wants to consolidate and enhance its existing retail niche. A new, creative approach is required to the way that service is provided. Imagine, at the first thought-generating session, you are brave enough to offer up an idea of your own and it gets immediately dismantled or squashed; you are not going to offer another idea. The situation (A) – request for ideas input has led to you being told you are wrong and a sense of personal discomfort (C). Next time around, you’re not going to offer an idea when requested as you believe that you will be told your idea is wrong (B). You may carry this belief forward throughout your career, despite changing contexts. This inner filter gets in the way of your creativity and your ability to bring all your resources to your work.

Imagine instead that your very first idea had been appreciated, had been savoured, built upon, integrated with other ideas and developed as part of the new service model. What a different belief system you might adopt.

This insight into the power of your inner world and the way your thoughts, actions and feelings are all intricately linked is used at the highest levels of performance, and is key to developing and sustaining performance and well-being.

In elite sports, “getting the mind right” is a basic phenomenon – yes, you need to train, to be at the top of your personal physical performance to be a sporting champion – but your mental preparation can make the difference between running a good race and running your best race.

BUILDING RESILIENCE AT A PERSONAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL LEVEL

“Promise me you’ll always remember: You’re braver than you believe, and stronger than you seem, and smarter than you think.”

Christopher Robin to Pooh (by A. A. Milne)24

There are numerous ways in which you can build your resilience. The ideas below are a few core offerings that come from a range of sources – and as you will see from other chapters, are not limited to enhancing resilience.

Self-acceptance: So often we are unfairly critical of ourselves. Accepting things is not about complacency, it’s about accepting and not judging – not beating yourself up.

For example, accept that you’re not perfect (nobody is!) and the feedback that you’re receiving becomes really helpful and useful. Make a realistic appraisal and, from this position, make changes. A stronger selfacceptance allows quicker self-righting and growth.

Befriending yourself: This is about imagining what you would say if a colleague or friend was in the same situation. The chances are you would not be so harsh to someone else as you are to yourself. So instead of thinking, “I was hopeless at the job interview”, stand back and think about someone you have great respect or care for. What would you say to them? Take the advice you would give to them and give it to yourself. Perhaps your inner voice would then say “Although I could not answer all the questions, in the circumstances, I gave it my best shot. At least it was good practice for my next interview”. In other words, you’re not ignoring the outcome, but you are able to build and move forward from the adverse experience.

Demagnification or “deawfulising” events: It is very easy to blow a situation out of all proportion and this will only serve to increase your stress levels. Although events may be difficult to deal with or unfortunate, ask yourself: “Is it really awful?”; “Is it the end of the world?”; “Is this a hassle or a horror?”

One story highlights this approach: a catering manager returned home late one night just after 1am but his wife, a paediatric nurse, was still awake in bed. “How was your day?” she asked. “Don’t ask. It was a disaster. Things never go wrong but tonight we had a dinner for 500 people and there was a problem in the kitchen. The vegetables for the dinner were not as hot as they should have been and the organizer was furious. He was shouting in my face. It was horrible. It has taken me 20 minutes to find a car park space and I am due back at work for 7am.” Her silence made him take a breath and ask “How was your day?” She responded: “Three babies died on me today”. Since that conversation, he has been able to deal with any situation he has faced in his career in the service sector.

Look for your strengths: Do more of what you are good at, do more of what works. For example, if you are good at establishing productive working relationships, volunteer for team-based projects.

Look for meaning: Consider what is happening to you, even when you would prefer that it wasn’t happening to you. What can you learn? What is good about this bad situation? Another hotel example (demanding service environments can really test resilience) provided an early lesson for a young hotel trainee manager. It was a Boxing Day fancy dress party with lots of (mostly elderly) people dancing around the room in various outfits. Suddenly, a female Robin Hood collapsed, unwell. At first there was panic but then a manager took charge, announcing that there would be a short break and asking people to go to the hotel bar or their rooms and an ambulance was called. The lady was taken to hospital and the party resumed, albeit in a more subdued fashion. The learning here was the importance of meeting the needs of those in the room – the lady who had collapsed needed immediate attention, her family needed care and some privacy and everybody else still wanted to enjoy their Christmas as much as possible. The trainee observed the importance of remaining calm, taking control, making decisions and considering the impact of decisions on all those present.

Be curious: What can you discover? Surprise yourself. Let’s take somebody who had been in awe of juggling from a young age and thought people were blessed with some natural gift to be able to do this. Then, after randomly receiving juggling balls as a present, he decided to give it a go. A few days later, after a couple of hours each day practising (and failing many times) he could juggle three balls. Surprised… and thrilled!

And finally, exercise: Yes, there is no getting away from it, exercise is good for physical and mental health. In terms of resilience, it can lift your mood, reduce stress levels and make you more alert. It may also improve your self-image.

“In the middle of difficulty lies opportunity”

Albert Einstein25

RESILIENCE AND 31PRACTICES

At the organizational level, the 31Practices approach is linked to building greater organizational resilience. The focus with 31Practices is on setting a very clear understanding of what the organization stands for, the role that the employee plays in representing them, and a unity of purpose. This clarity helps all employees to perform at their best, mentally and physically, as they can more easily trust the assumptions that they are making. They have a clear view of the shared assumptions in the room and can therefore work with more confidence and trust that others will have (at least some) of the same internal filters.

Recently, an automotive executive commented on the great benefits that would be generated by an employee in a car showroom in New York, knowing that the Practice of the day was to focus on personalizing the customer service, and at the same time knowing that everyone in branches in Paris, or Beijing or Moscow had the same focus that day. He saw how this would create a sense of belonging to the larger organization and an enabling inner belief.

Want to know more?

• Srikumar Rao offers an insightful talk to Google about his book Are you ready to succeed: Unconventional Strategies to Achieving Personal Mastery in Business and Life. The talk can be accessed on http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u20vVbhpM50

• A well known oldie in this area is Tim Gallwey’s series of inner game books. The first in the series: The inner game of Tennis was first published in 1975. The books are very readable and definitely recommended. Tim Gallwey (1986). The Inner Game of Tennis. London: Pan books

• The second resource we point you to is one that we have referenced frequently in this chapter. It’s highly readable. Coming from the world of psychotherapy and coaching, rather than the world of sport, the context is different, the underpinning ideas are similar – and there are some really useful practical exercises throughout. Michael Neenan (2009). Developing Resilience: A cognitive-behavioural approach. London: Routledge.