13

CHAPTER 13 MINDFULNESS

“Whatever the present moment contains, accept it as if you had chosen it.”

Eckhart Tolle1

Mindfulness essentially means moment-to-moment awareness of heart, mind and body. It’s about purposefully and non-judgementally paying attention to the unfolding experience of each moment.2 This awareness enables you to make choices about how and what your mind attends to, how you act and how you react to events. The idea of noticing “with friendly curiosity” makes mindfulness a compassionate activity. This developed awareness is available to everybody through mindfulness practices.3

MINDFULNESS – WHAT DOES IT DO FOR US?

Mindfulness practices are not new; they have emerged from traditions in middle and eastern collectivist cultures for whom meditation and other techniques promoting enlightenment and self-mastery are more central. From our own observations, we believe these practices are of growing interest in western cultures where ideas of individualism and environmental mastery have typically dominated.

Mindfulness is about creating distance from our immediate experience so we can take a moment to reflect, review, and consider how to move forward. This ability to be more of an impartial spectator on the noisy emotions and thoughts that are constantly produced internally develops to the extent that we can more easily choose what to attend to and how to respond.

Being “mindful” of the state that we are in (happy, angry, sad, bored) and the thoughts that drive that state enables us to choose to be in a different state at any one moment. Mindfulness is not about denying anger, or bottling up frustration. It’s about skilfully choosing not to get frustrated or angry in the first place – choosing that a different response will achieve the purpose that we want to achieve.

Without attention to our inner world, we can find ourselves tossed along on wave after wave of thought and emotion without any insight about how to manage this onslaught; reacting on “auto-pilot” to whatever emerges.

In the workplace, you may notice when people around you spend more time worrying to themselves and to others about just how much work they have to do, how unfair it is, or how difficult it is. You may have witnessed how this creates distress and keeps them “stuck”, unable to move into a more resourceful state. In this situation, people often find it difficult to step back and see themselves, what they are doing and the impact of their approach on themselves and others. They’ve lost the necessary distance to appreciate the bigger reality.

Mindfulness is like getting back into the cockpit of your own mind and giving yourself more control.

As well as internal awareness, mindfulness raises awareness of the context you’re in – observing things as they are rather than believing they should somehow be different. When you see things as they are and don’t label or judge the events taking place around you, you are freed from your normal habits in how you choose to react to them.

Images of mindfulness practice tend to invoke the need for years of retreat, Buddhism and hours of daily meditation. Actually, in a recent study of students at Dalian University, Yi-Yuan Tang4 and his colleagues demonstrated that a programme integrating body–mind aspects of meditation can, when practised for 20 minutes a day for five days, enhance self-regulation, attention, ability to be present in the moment and reduce the baseline stress level (measured by the level of the stress hormone – cortisol).

An interesting convergence between traditional mindfulness practices and developments in neuroscience now enables us to understand the physical basis for the impact and value of mindfulness practices.5

“One man that has a mind and knows it can always beat ten men who haven’t and don’t”

George Bernard Shaw6

MINDFULNESS AND ORGANIZATIONS

So what sense does this all make in the context of organizations? The work of Daniel Siegel (and others) indicates a number of aspects of physical and mental functioning are enhanced through mindfulness practice including:

• improved emotional regulation

• improved ability to heal and sense of well-being

• enhanced interpersonal relationships (through attuned communication, greater empathy, intuition and response flexibility)

• a greater ability to focus and attend to the present moment7

Reviewing the potential benefits, the question is not “What sense does mindfulness make in the context of organizations?”, but rather, “In what context would mindfulness not make sense in organizations?”

There is evidence globally about the negative impact of stress on health and well-being; on toxic emotion in the workplace (impacting both the individual concerned, colleagues, and the organizational system); on poor working relationships (making it harder to get things done); and the impact of stress on society manifesting in mental and physical ill health. If mindfulness really is a practice which enables individuals to increase their health and effectiveness (in and outside of work), there is little to argue against embracing it.

A number of respected businesses have implemented mindfulness programmes,8 including Apple, McKinsey & Company, Deutsche Bank, Procter & Gamble, Astra Zeneca and Google.

Mindfulness at Google

Google has a fast-paced, hard-driving culture.9 Co-founder and CEO, Larry Page, promotes a “healthy disregard for the impossible”. In this pressurized culture, mindfulness training has a standing and reputation you might find surprising. Chade-Meng Tan, who introduced the programme, is both a lifelong Buddhist and rich (due to being only the 107th person Google hired) – but that isn’t enough to sustain the reputation of the mindfulness programme.

An engineer at Google sees “business as a machine made out of people” with the mindfulness training as “a sort of organizational WD-40, a necessary lubricant between driven ambitious employees and Google’s demanding corporate culture. Helping employees handle stress and defuse emotion – helps everyone work more effectively”10 “in a high IQ environment, IQ is not the differentiating factor, but emotional intelligence, EQ, is”.11 There are many personal experiences shared at Google that evidence the value gained from the mindfulness training, enabling people to get a handle on their experience of stress and strong emotion.

Mindfulness at General Mills

General Mills is a large global food provider, with offices and manufacturing facilities in over 30 countries. Global brands include: Haagen-Dazs, Old El Paso, Green Giant and others. General Mills has offered mindfulness training for seven years and it has become part of business as usual. The founder of the programme, Janice Maturano, states mindfulness is “about training our minds to be more focused, to see with clarity, to have spaciousness for creativity and to feel connected – to be compassionate to ourselves and to others.”12

The mindfulness programme at General Mills has demonstrably increased effectiveness. Nearly four times as many employees focus daily on their personal productivity after participating in the mindfulness programme (up from 23% before to 83% after). Most senior executives who attend the programme also report a positive change in their ability to make better decisions, with nearly all reporting becoming better listeners.13

Mindfulness, it seems, impacts on employee performance, well-being, and will inevitably impact on the organizational system. It doesn’t have to be introduced as something separate to other development initiatives. On leadership development programmes, mindfulness practices may be introduced as simple breathing exercises or the practice of “presencing”: bringing attention and focus to the present moment.

MINDFULNESS – SOME CORE PRINCIPLES

“Every human has four endowments – self-awareness, conscience, independent will and creative imagination. These give us the ultimate human freedom... The power to choose, to respond, to change.”

Stephen R. Covey14

Awareness leads to choice

The core purpose of mindfulness practice is enlightenment, or the awareness of the reality of things. Clear understanding of what is taking place right now prevents us being deluded.

It sounds simple.

Yet, so often, we are wrapped up in the noise of our minds, drawing our attention to the future to an imagined event, or to some past event. We associate emotions with these events and become hooked into what might be possible (future), or perhaps some restless replaying of a past frustrating conversation. Living in the past or future prevents us being aware of what is happening to us in this moment.

Right here, right now, we are on auto-pilot, letting our assumptions and habits guide our immediate responses. Greater mindfulness enables us to bring ourselves back to now, and make more skilful choices about how we want to respond in the moment – choosing how we want to feel, what we want to think and how we behave.

The compassion within mindfulness practices allows us to accept ourselves (warts and all) without judgement, enabling us to examine more closely those things about ourselves that we might struggle with or want to deny about ourselves.

For example, take the senior manager who gets emotional when frustrated with colleagues in the work place. He is so upset by his loss of control and appalling behaviour that he cannot accept that this is him. He refuses to accept the evidence (feedback) and locks it away.

Imagine being able to look at those emotional outbursts without judging himself (with a compassionate mind). He may then, through careful exploration, understand the triggers, and with a little more discovery, understand some of the different choices he had about how he might respond. He might learn to stop, breathe, notice what is happening to him, reflect, and respond based on choice rather than based on a knee-jerk habit.

With skilled mindfulness habits, rather than avoiding uncomfortable experiences, we are much more likely to simply notice them, be curious about them, choose what response we want to give and move on.

“Feelings come and go like clouds in a windy sky. Conscious breathing is my anchor.”

Thich Nhat Hanh15

Focusing

One of the myths of business is the “skill” of multitasking. Multitasking is shifting attention back and forth between activities very quickly. Mindfulness practice helps you focus your attention more effectively, being fully present to the activity you are engaged in – getting it done and moving on.

Multitasking does not make you effective.16 A study at Kings College London found workers distracted by email and phone calls suffer a fall in IQ more than twice that found in marijuana smokers. In this super-connected world, we are constantly scanning for opportunities and staying on top of contacts, events, and activities in an effort to miss nothing.17 According to one study, it can take up to 25 minutes to fully re-engage with the task you have distracted yourself from by answering an email, or responding to an interruption.

The art of paying attention is something that great minds attribute to their success, and equate to greater wisdom. Integrated learning requires focused attention rather than the scattered crumbs of attention we might be tempted to give when “multitasking”.

Mindfulness is one route to being able to carefully attend and be present to the current moment, learning to focus on what is now the priority, while putting distractions out of our minds.

“There is time enough for everything in the course of the day, if you do but one thing at once, but there is not time enough in the year, if you will do two things at a time.”

Lord Chesterfield18

Presence

Mindfulness practices enable us to be more present. When we are more present, happy to accept rather than struggle for control, we release energy, relax, let go of judgements and regrets. We look fully and openmindedly at where we are, giving greater choice. We enjoy greater health, well-being, and clarity.19

Peter Senge and his colleagues describe Presence20 as full consciousness, being fully aware in the present moment and open to what might emerge (beyond assumptions normally held). Presence is also about letting go of old identities and the need for control. All these aspects together allow things to emerge – “letting come”.

Some see presence and the capacity for reflection as the true attribute of wisdom.21 Mindful presence can enable us to see that information is contextual rather than truthful or “fact”.

Overfamiliarity, routines, habits all prevent us from paying attention to what is really happening now because we see what we expect to see – we make reality fit our assumptions. In this state, we don’t let things emerge or new ideas come forward. Building our ability to be present helps us to slow down and see what is happening rather than seeing what we expect to happen. Greater awareness, where we are performing tasks in situations that are highly familiar to us, means we can cultivate conscious awareness and greater competence.

MINDFULNESS AND 31PRACTICES

31Practices is a methodology designed to bring greater attention to how you are “being” rather than a focus on “doing” alone. Core to 31Practices is enabling individuals and organizations to be mindful of their core values and purpose, and how they might practise those values and achieve their purpose, by focusing on just one at a time, each day. Over time, focusing on one Practice at a time builds strong habits that support individuals and organizations to be the best that they can be.

A key part of 31Practices is for people and organizations to notice what they are doing, make choices about how they are being, and to raise awareness about their impact on different groups of stakeholders.

The principle of one Practice a day not only builds strong habits, but also allows us to bring that one Practice to mind and be present with how we are “being” and what we are doing about that particular Practice. Perhaps all employees know that they should display “meticulous attention to cleanliness, tidiness and presentation”. However, to have this front of mind and taking responsibility for what you do about it today makes a difference. Suddenly, you see things that you would not have seen and you are ready and prepared to act… so you do.

This idea of one Practice at a time as part of awakening or enlightenment is, as we discovered, not new. In writing this book, we came across the 37 Practices of the Bodhisattva.22 A Bodhisattva is “one who seeks awakening”23 and enlightenment. We like to believe that 31Practices is in good company.

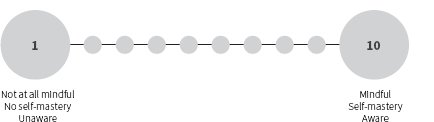

Exercise – The mindfulness continuum

The alternative to mindfulness is living a life where you are on auto-pilot (mindless): living without thinking “how”, responding without thought, continually at the mercy of ever-changing conditions that you give yourself absolutely no control over – the world around you, and your unchecked responses to that world, has you hooked. You have little or no awareness that you are “hooked” and no skills to unhook yourself. There are many points along the continuum between the two extremes. You might like to try this exercise yourself or with your colleagues/team.

1. Where are you on this continuum now?

2. Do you believe that it is helpful to have control over your emotions and behaviours?

If your answer to question 2 is sometimes, or yes, please answer questions three to six below:

3. To what extent do you feel you have a choice about how you feel when you are experiencing a particularly strong emotion (e.g. anger, fear, happiness, sadness)?

Where would you put yourself on the continuum between 1 and 10 when experiencing strong emotion? Put down different ratings for different emotions if they give you a different sense of choice.

4. During what % of your day do you feel you have a choice?

Looking back at your answers to questions 3 and 4 – what do you notice? What patterns do you see?

5. Are there times when you really DO feel that you have a choice about your emotional response and / or physical response?

Great… you’ve left the starting blocks on the road towards greater mindfulness.

6. Are there times when you really DON’T feel you have a choice about your emotional and even behavioural response?

Welcome – join the majority of people on the planet – you’ve got some way to go before reaching the “self-mastery” end of the continuum.

Would you like to have a sense of greater choice, mastery and mindfulness? If so, read on to explore some simple techniques.

Mindfulness: some simple techniques

“Mindfulness isn’t difficult, we just need to remember to do it.”

Sharon Salzberg24

Noticing: At Google, one of the practices taught on their Search Inside Yourself programme is simply: Stop, Breathe, Notice, Reflect and Respond.

• Stop what you are doing

• Breathe (three in and out breaths from your gut not your chest)

• Notice yourself – your emotions, your five sensations

• Reflect – what do you need to do here? What is your intention? What is your purpose here?

• Respond

Building this collection of practices enables you to catch yourself even in the most potentially emotional of situations and choose how you want to respond.

Mindfulness exercises for the super busy:

• Spend at least 5 minutes each day doing nothing

• Get in touch with your senses by noticing the temperature of your skin and background sounds around you

• Pay attention to your walking by slowing your pace and feeling the ground against your feet

• Anchor your day with a contemplative morning practice (e.g. breathing meditation or any other)

• Before entering the workplace, remind yourself of your organization’s purpose and recommit to your purpose

• Throughout the day, pause to be fully present in the moment before undertaking the next critical task

“By letting it go it all gets done. The world is won by those who let it go. But when you try and try, the world is beyond winning.”

Lao Tzu25

Want to know more?

These alternatives on further reading around the mindfulness approach the subject from different perspectives. Ultimately, all lead to the same destination.

• Daniel J Siegel (2007). The Mindful Brain: Reflection and attunement in the cultivation of well-being. New York: Norton.

• Bhante Henepola Gunaratana (2002). Mindfulness in Plain English: A Practical Guide to Mindfulness of Breathing and Tranquil Wisdom Meditation. Somerville, MA: Wisdom Publications

• Liz Hall (2013) Mindful Coaching: How mindfulness can transform coaching practice. London: Kogan Page.

This seminal book on Presence and Theory U offers a rich story-based journey to the discovery of the power of presence in organizational work.

• Peter Senge, Joseph Jaworski, C. Otto Scharmer and Betty Sue Flowers (2005). Presence: Exploring profound change in people, organisations and society. London: Nicholas Brealey.