16

CHAPTER 16 PRACTICE

“The more I practice, the luckier I get.”

Gary Player1

Practice is about applying an idea, belief or method rather than the theories related to it. Practice in this chapter is also about repeatedly performing an activity to become skilled in it.2

“Practice is a means of inviting the perfection desired.”

Martha Graham3

The value and benefit of practice is taken for granted for performers at the highest level in fields such as sport, music, and art. Can you imagine teams like the New York Yankees in baseball, Toronto Maple Leafs in ice hockey, Dallas Cowboys in American Football, Manchester United in soccer just turning up on match day? In the arts, would the cast of Cirque du Soleil, the musicians of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra or the dancers of the Bolshoi Ballet just turn up on the day of the performance? Even the Rolling Stones practise.

From the sporting world we see that anyone who wants to learn and improve needs to commit time and effort to practise, to notice what works and doesn’t, to keep training until a routine is improved, perfected.

How does this translate to organizations? Training exists of course – focused on new recruits or “teaching” new skills and technical knowledge that may be required. Skilled execution is highly valued. But, in most organizations, there is not much focus on practice – and a lack of focus on reflection – on learning from that practice, considering what worked, what didn’t work and what to adjust next time. In organizations, practice and reflection are the missing links between the theory – the idea, and skilled execution.

A further common assumption that we make is that skills are purely physical and visible – some are, but many skills are not. Have you ever noticed the routines of top sports people coming out to deliver their personal best at any sporting event? The external habits are easy to see, the touching of a chain, adjusting a cap. These are backed up by a host of internal habits and routines. Skills bloom from a fertile and resourceful set of inner beliefs, ideas and attitudes.

“The mind is what separates a fair player from a true champion”

Kirk Mango4

WHAT DOES PRACTICE DO FOR YOU?

Practice enables you to broaden your repertoire, to deepen your knowledge, insight and capability. The brain, once thought to be a “fixed” entity, is malleable. Purposeful practice builds new neural pathways and constant repetition deepens those connections, making that new option a readily available choice.

The result of all this practice? The seemingly super-sharp reaction time of various ball sports is an illusion. In standard reaction time tests, there is no difference between, say, a leading tennis player compared to people in general. BUT, the player is able to detect minute subtle movement in the server’s arm and shoulder which from years and years of practice has led them to read the direction of the serve before the ball has even been played. It’s this practice that has created unconscious patterns and distinctions that the player responds to equally unconsciously – resulting in the seemingly super-sharp responses in the professional game.

Wayne Gretzky, a Canadian ice hockey player, has been described as the greatest ice hockey player ever by many in his field. His talent captures this attention to the context of a game rather than focusing on distinct actions alone. “Gretzky’s gift…is for seeing…amid the mayhem, Gretzky can discern the game’s underlying pattern and flow, and anticipate what’s going to happen faster and in more detail than anyone else.”5

The same is found in experts in many fields. They instinctively know – based on years of practice. They are able to pick up minute distinctions and patterns that the rest of us are blind to.

The story of a Cleveland firefighter, shared by Malcolm Gladwell.6 The fire was in a kitchen in the back of a one-story house in a residential neighbourhood. On breaking down the door, the firefighters began dousing the fire with water. It should have abated, but it did not.

The fire lieutenant suddenly thought to himself, “There’s something wrong here”. He immediately ordered his men out. Moments later, the floor they had been standing on collapsed. The fire had been in the basement, not the kitchen.

When asked how he knew to get out, the fireman could not immediately explain the reasons – the implicit knowledge, built up over years of experience, triggered an almost instinctive reaction – which saved his life and those of his fellow crew members.

The story of a head chef. A catering company introducing software to calculate the cost of producing a dish (data for the recipe and cost of raw ingredients) decided to compare the cost calculated by the package with the calculations from the head chef. The difference between the two costs was minimal. The head chef had practised this calculation thousands of times over a number of years with variations in price and recipe, developing an instinctive subconscious ability to make an accurate calculation.

Purposeful practice is the primary contributing factor (above natural talent) to excellence in sport and life.7 To be a truly practised at a skill or habit, hours of sustained practice are required – estimated at 10,000 hours (2.7 hours a day for 10 years8). This finding has been validated across professions. The focus and attention to the practice and learning from that practice is fundamental.

At this level of competence in a particular skills context, you have developed what is described as reflection-in-action – where you are critically aware of what you are doing while you are doing it – judging each moment for its suitability against an inner set of criteria – at the same time that you are actually doing the activity.9 It’s this attention to practice that enables you to keep performing at your best.

“It’s not necessarily the amount of time you spend at practice that counts; it’s what you put into the practice.”

Eric Lindros10

LEARNING THROUGH PRACTICE

How do we learn through practice? As in many things, attitude – how we approach the task and what we expect of ourselves – is of paramount importance. Here are some ideas to bear in mind about the process of learning through practice.

It’s uncomfortable – you feel vulnerable, exposed. Through practice you are making the unfamiliar familiar. When you do something for the first time it feels clunky, uncomfortable. You are likely to feel a bit self conscious at best, and downright scared of failure and associated shame at worst – you might feel absolutely sure that everyone else notices that this is the first time you’ve done this, certain that others can see all your mistakes. Initially, your performance might take a turn in the wrong direction – getting slower rather than faster – as you start to work out how to integrate a new awareness or activity into your repertoire. With repetition, that painful self-awareness subsides and you now can perform the task (whether it’s speaking to an audience of 300, operating the photocopier or completing an internal approval form) with confidence and elegance. You’ve integrated the learning into “business as usual” and you’re ready for the next challenge.

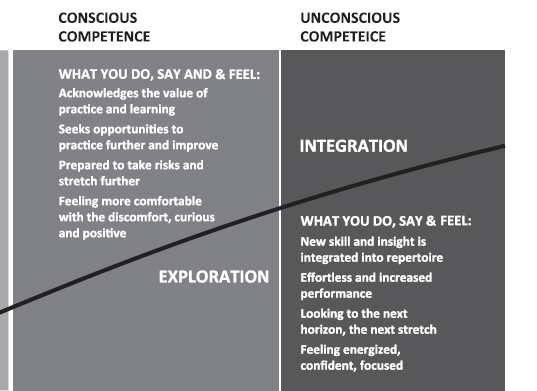

Practising something new takes you into a four-stage learning and performance cycle.11

• Unconscious Incompetence – you don’t know that you don’t know – and you might react with some defensiveness to feedback or the awareness that you might need to change something. You feel vulnerable when you start to become aware.

• Conscious Incompetence – you know that you don’t know and you still can’t do it – it’s uncomfortable, confidence drops, you might be more worried and you still feel vulnerable.

• Conscious Competence – you know that you know how to perform the new skill – but it requires attention, focus and energy. You start to feel more confident and are practising and stretching your new skill.

• Unconscious Competence – you don’t know that you know – it just seems so easy. Your new skill is an integrated habit – you perform the skill without conscious effort.

Is this model familiar, or if you haven’t seen the model before, do the stages of learning sound familiar? And the thing is, you don’t get the learning if you don’t go through the stages of incompetence (unconscious and conscious). The saying goes “No pain, no gain”. To reduce the level of pain, remember that feedback is only data. Be curious about what you might learn rather than be defensive. This gives people around you permission to grow and learn too. Interestingly, people often respond very positively to the humanity displayed when you are open about your learning.

A fifth stage to this model has been described as developing reflectionin-action, or reflective competence – avoiding the onset of complacency leading to mistakes and a degradation of the skills that have been learned. In part this is ongoing critical reflection, and it’s also about maintaining a “beginner mind” (see Chapter 18, Discipline). Building this reflective competence is something that can support you to build mastery.12

“Failure” is part of the territory – Paradoxically, failure is a key part of success. Framing failure as an opportunity to learn is a key to building success. For example, Shizuka Arakawa, one of Japan’s greatest ice skaters, reports falling over more than 20,000 times in her progression to become the 2006 Olympic champion.

It is relatively well known that Thomas Edison “failed” many times before he had success. One story is that while Mr. Edison was inventing the light bulb, a young reporter came to interview him. At this point, Mr. Edison had tried over 5,000 different filaments for the light bulb with no success. The young reporter asked “Mr. Edison, what is it like to have failed over 5,000 times?” To which Mr. Edison replied, “Young man, I haven’t failed at all. I’ve succeeded at identifying 5,000 ways that don’t work!” Edison’s drive wasn’t diminished at all. He continued and made more “mistakes” before he finally “succeeded” in creating the first filament light bulb.

“Practice is the best of all instructors.”

Publilius Syrus13

Excellence comes from pushing at the boundaries of what is thought to be possible – Practice leads to excellence from constantly stretching to reach a much higher goal (often a goal that only the coach/manager thinks is possible). Thus practising with (and being with) the best is critical to drive up performance and mindset.

“When you are not practicing, remember, someone somewhere is practicing, and when you meet him he will win”

Ed Macauley14

One of the reasons Brazil is so successful at soccer is because most of the footballers played futsal. The surface, ball and rules create an emphasis on creativity, technique, precision and more frequent passing.

Linking heart, mind and body – practising any skill (even imagining success at a particular skill – see Chapter 22, Neuroscience) is a full mind, heart and body event. As you build new physical skills, you’re laying down and deepening neural pathways. As you develop competence and strength in a particular skill, you’re building up the positive emotions associated with execution. Practice in something can lead to belief in your ability to do it. This principle is one that informs coaches and practitioners working in the area of somatics and embodiment.

So if you embody confidence, in how you stand, walk, and engage with others, you will believe that you are confident – try it.

“In theory, there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”

Yogi Berra15

SO WHAT?

How can organizations create the culture and space for practice in order to grow and learn, improve and deliver excellence? Individual practice at work is a systemic question – it’s about the prevailing culture, skills and process – as well as individual focus and motivation.

Specifically, what is the “feedback culture” of the organization? To what extent do people receive good quality feedback in a relatively “safe” environment (i.e. not a critical performance environment) so that they can learn and improve – getting it right when it really matters?

An organization with a blame culture will limit people’s motivation to practice. And it will suffocate learning and growth. Employees will look to hide and deny mistakes rather than own and learn from them. Such an organization will limit its ability to adapt and change, and within a fast-changing global context, such a limitation may well lead to demise.

It’s not just about avoiding a blame culture – how can you establish an environment of striving to achieve the best and an expectation that this will be achieved? Everybody then benefits from the virtuous circle of being with others who are excellent at what they do. This “multiplier” effect impacts across groups and communities:

• The city of Reading, UK produced more outstanding table-tennis players than the rest of the country put together.

• Spartek (a small, impoverished area in Moscow) generated more top 20 women tennis players than the whole of America.

• The high altitude Nandi area in Kenya has produced more marathon runners than anywhere else in the world. The area is so poor that children would regularly run to school (up to 10 km away).16

What are the processes in place to support practice?

Take the example of the executive meetings in a media organization. Part of these meetings were dedicated to presentations and input from key senior employees. Securing a slot to present to the executive group was key to developing your profile as a senior employee with the prize being future consideration for promotion to the executive group. Each senior manager presenting was carefully supported to scope, map out and practise their presentation. At each stage, feedback would be given and integrated into the next iteration until an incredibly slick and professional presentation was crafted for delivery to the executive group.

Practice and learning take time and focus – and often the pressure to deliver means the time to implement the theory is missed – and a lot of time and money is wasted in the process.

Every person who has responsibility for leading others, from the supervisor to the CEO, needs skills to support practice and learning. And they themselves need to be supported to learn and grow in these “soft skills”.

PRACTICE AND 31PRACTICES

31Practices is about putting values into practice every day. Left on the boardroom wall, or turning up only on the marketing and recruitment literature, means the values are theoretical at best. To become part of the fabric and the way of being, the values have to be practised.

Because there is a Practice each day, everybody in the organization has the opportunity to practise one behaviour directly related to one of the core values. For example, an organization may have the core value “Relationships”, and a Practice to bring this value to life, “We invest time with stakeholders to build long lasting relationships”. On the day of this particular Practice, all employees are therefore very mindful and consciously looking for opportunities to build strong relationships with colleagues, customers, suppliers, communities. The impact? Let’s consider:

“Today, instead of sending an email update, I took the time to call the project sponsor and ask her what she was noticing, and what did we need to start, stop, continue in her view. I learned that a key team member was in the process of resigning for personal reasons – something that was not widely known – this information enabled me to think through the delivery schedule and prepare a shift in resource to come into play when the news was made public. The call took five minutes – it would have taken me longer to compose the email. I felt great.”

Over the course of one month, you live each of the organization’s values through a number of different Practices. Initially, like any new activity, you may feel uncertain, perhaps even a little anxious: “Am I doing it right?” Over time, the Practices are repeated, becoming habitual – you don’t have to think about them and they become automatic. You will find that you start adopting the Practices more generally, not just the one that day.

This works across small and large groups. Marriott’s Daily Basics programme was based on the same principle and operated across 3,000 hotels globally.

A key point for us is that, just as with sport or other activities, hours of purposeful practice of behaviours and attitudes that are hard-wired to the organization’s core values will result in a strong values-based culture (if we take the view that culture is the “way things are done around here”).

MAKING PRACTICE A REALITY

Try this exercise with a group of colleagues – it’s about how you connect with and greet people.

Ask everybody to walk around the room in a random fashion.

Explain that you are going to shout out a number between 1 and 10. When you shout a number, the idea for the participants is to greet the person nearest to them in accordance with the number they have just heard you shout. The number 1 represents a poor effort at greeting and welcoming the other and 10 represents excellence.

When the greeting has happened ask the participants to walk on.

Repeat with different numbers so that they practice greeting at different levels and finish with a high number.

After the exercise, ask people how they felt about receiving greeting 8, 9 or 10. In our experience, people really enjoy receiving a warm, friendly greeting. Then ask them to be honest with themselves and consider what number greeting they give to others each day. Again, we find that people often admit to giving between 5 and 7. You can leave them with the thought that, if a warm greeting feels so good, then why not give this warmth each day. It is their choice and it is easier with practice.

There is another very simple way to experience the benefit of practice: start something that you have never done before and practice regularly and to the right level of quality. This could be something very basic like juggling, memorizing and repeating some phrases in a foreign language or playing a tune on a musical instrument.

Want to know more?

• Matthew Syed (2011). Bounce: the myth of talent and the power of practice. New York: Harper Collins

• An example of some of the research studies looking at the details of the impact of practice is provided by the paper by Avi Karni et al. Avi Karni, Gundela Meyer, Christine Rey Hipolito, Peter Jezzard, Michelle M Adams, Robert Turner, and Leslie G. Ungerleider (1998). The Acquisition of skilled motor performance: Fast and slow experience-driven changes in primary motor cortex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA). http://www.pnas.org/content/95/3/861.long