19

CHAPTER 19 COMPLEXITY

“Snowflakes are one of nature’s most fragile things, but just look at what they can do when they stick together.”

Source unknown

Organizations are complex adaptive systems. They consist of interconnected, interwoven parts or sets of things that work together as part of a mechanism or interconnecting and dynamic network.1 Ralph Stacey2, an eminent figure in the field of complexity, points out that all human systems are “self-organizing” and not open to control. Interactions between humans are co-created and emergent, with multiple possible outcomes at each point of engagement.

A complex environment consists of any number of competing factors, combinations of agents and potential outcomes.3

Let’s bring this idea of complexity into concrete reality. Just pause and imagine the day in front of you. What are the things competing for your attention? What are the different roles of each of the people you interact with? What different levels of responsibility do you have for the tasks on your plate? What are the multiple contexts within which each of those people, tasks, roles exist? What might the impact be for any one of those people or tasks depending on how you engage with what’s needed? Get the picture?

The picture is constantly shifting, depending on what is changing in the relationships between each of the component parts. If I choose to respond to the email requesting a decision about a simple project, other people take action, an output is generated, something now exists that didn’t exist before, the system adapts and the patterns recur again and again. It’s a bit like looking at life as if it were a kaleidoscope – seeing things shift and move radically as a result of a small movement somewhere in the system.

From this perspective of complexity, very small interventions or chance occurrences in one interaction can have very large, unpredictable or unknown effects. As James Gleick described, the butterfly effect – tiny differences in input can quickly become overwhelming differences in output – a butterfly stirring the air today in Peking can transform storm systems next month in New York.4

One small example of the butterfly effect that springs to mind happened very recently. Alex, the head of a function in a very hierarchical organization, was heard musing that it might be a good idea to deploy two people from one departmental team elsewhere to support a project for a short time. No sooner than the words had escaped his mouth, the rumours began, and anxiety started to spread in the department where the two people were currently employed. Eventually, the “decision” (as it had now become) to deploy people out of his team reached Connor, the head of the department in question. A meeting was arranged and through some careful exploration and discussion between Alex and Connor, the decision that had never been made was reversed. What started as an innocent thought spoken out loud had some significantly bigger and unintended consequences for individuals across part of the organization.

Another example is from the restaurant sector. A facelift and new menu had been introduced to a restaurant in London to make it more “current”. The changes had been well received by customers and early signs were positive that there would be a significant increase in sales and profitability. One of the senior executives of the owning company visited for lunch and, as he was leaving, mentioned to the local managing director that he thought there could be more grill items on the menu. As a result of this comment, a decision was made to change the menu concept completely to become grill based. What was the impact? For a period, the restaurant was less busy until the menu balance was restored. Just as importantly, the new direction completely demotivated a number of the leadership team who had been responsible for developing the successful new menu concept that the senior executive had commented on.

An example of complexity in action familiar to us all is the viral impact of social media. Those calling for change in the Arab Uprisings in spring and summer of 2011 used social media channels to raise global awareness of events and conditions in countries along the north of Africa and into the Middle East. The viral and uncontrolled use of social media perhaps facilitated a quicker (although not necessarily easier) pathway to change than otherwise might have been the case.

The rise of social media and indeed community platforms in the workplace act as an accelerant for complex processes. In practice, this means that a different, more nimble, skilled and open approach to leadership and management is needed. Achieving effective outcomes is more about people interacting to arrive at an end goal, with a need to adapt to any changes on the way and the ability to add new thinking as it emerges. The approach to making a product where certain people do certain things at certain times as efficiently as possible is no longer fit for purpose and has a limited application.

In the 2010 IBM survey5 of executives, CEOs noted their primary challenge was operating in an increasingly complex, volatile and uncertain world. And almost exactly half of these high-achievers felt ill-equipped to personally manage the challenge of this complexity and succeed.

A very insightful point was made by Donald Schön6 decades before: “managers do not solve problems, they manage messes”. He points out that problems are extracted from messes by managers through the process of analysis.

Even the problems in front of us are only present from a particular perspective.

SO WHAT?

What does this all mean and what sense can we usefully make of complexity thinking to navigate everyday situations? Here we draw out some core ideas and principles a little further.

Relationships

Complexity thinking offers a radical relational view of the natural world.7 From this view, things exist in relation to other things and relationships are a core part of the way that we understand the world. Taken a little further, through local interactions (micro interactions) and micro behaviours, big patterns and events unfold and occur.

The reality that we experience is self-organizing, dynamic and emergent. The parts of a system are forever influencing and being influenced. In sum, the elements of the world exist through their relationships with other elements. We experience the world as sets of related elements and things happen as a result of the relationships between things.

Let’s take an example that purposefully changes the view of the relationship we have to each other. Peter Hawkins shares a mantra he uses as he travels on the underground rail network in London.8 Rather than viewing the people he is thrown together with as strangers, instead he uses the practice of repeatedly reminding himself as he passes people “you are my brother; you are my sister”. Have a go yourself when in a crowded space, there is almost a physical shift in your posture as your perspective of the relationship changes.

From a complexity perspective, paying attention to your relationships and how things are connected really is core to enabling things to emerge. The small things you affect in your relationships with others are the root of larger patterns and shifts.

As a different example, take the organization of an event. There is an enormous amount of background preparation that can stretch for 12 months or longer before the event itself, involving teams of people that each have a very small part to play in the creation of the larger whole. How those relationships between the parts emerge can make a significant difference to the experience of organizing the event, the eventual output and the experience of clients on the day.

This relational perspective can be a challenge to understand. In the west, the tendency is to view ourselves as separate to others. But, as individuals, we are actually defined (individually and organizationally) through our interactions with other people and other things.

A view based on our relationship to others emphasizes paying attention to “how” you operate, not necessarily the technical knowledge (the “what”) that you bring.

Linearity vs. Chaos

One of the core assumptions that remains pervasively embedded is that things can be reduced down to linear relationships between different things, that these can be measured “objectively”, and things can be controlled and predicted with certainty. This assumption of linearity and rationality is a dominant factor in the workings of organizations with little attention paid to the science of self-organization that happens in complex systems, coexisting with the law of linearity. All systems are self-organizing and imposed linearity will be ultimately self-organized and what appears chaotic will fall into or have a self-organizing pattern.

For anyone reading this who’s rolled out a process across an organization, there is a familiar chime to the refrain “well, we know that this was intended to be operated in this particular way, but we’ve adapted it, as in reality this is how it works best here”. For a project manager this is frustrating; for a brand, this could be disastrous. So if we accepted the selforganizing nature of systems, how can we build this consideration into process development and project management?

How can you clarify the outcome and vision sufficiently, and create the principles around which a system can self-organize, so that the outcome is aligned and enabled within a particular context?

Feedback loops

It’s argued that systems exist in balance and all attempts at change are pulled back towards a general state of equilibrium. The idea of feedback loops is a bit different – Ilya Prigogine9 talks about positive and negative feedback loops. Positive feedback loops are catalysts which enhance tendencies, and negative feedback loops dampen those down. There are many biological processes which use the output of one positive loop as the input into another positive loop (a self-catalytic loop).

Let’s imagine how this might apply to organizations. Take for example, Jo, a local authority director, who has been asked to take responsibility for delivering a particular piece of work by her colleague Mark. In the past, Jo would have said yes, but then would have struggled to deliver due to her very high workload. As a result she would have been depleting her own personal resources though lack of sleep and stress, she would be likely to have missed the deadline, or be too rushed to do the job she would have liked to have done, and possibly failed to do as good a job as expected with her other commitments.

What might have started as a positive is dampened by the reality of the experience of delivering, and the trust and professional relationship between Jo and Mark suffers.

Lets imagine Jo has said “No”, shared the reasons why and offered Mark some alternatives. What was a positive decision for Jo and for Mark then builds the relationship between Jo and Mark, increasing the level of trust and certainty between them, leading to a further positive experience. Perhaps an example of a self-catalytic loop.

What positive feedback loops are you creating today? What are you dampening down, reducing, due to a negative feedback loop (real or imagined)? What needs to shift to create more positive energy?

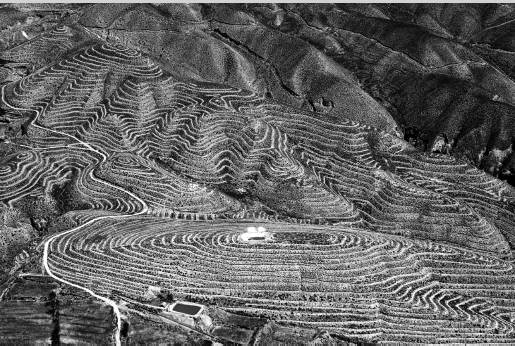

Fractals and patterns

Fractals are irregular, similar (but not always exactly identical) patterns across different scales or sizes. Think about the leaf of a fern or bracken, or a Romanesque broccoli – these are great examples of fractals found in the natural world. In the organizational world, think about the pattern of behaviour of those at the core of the seat of government and how that is reproduced across the different levels of government and out across society. The behaviour of the executive team in a business and how they interact is mirrored throughout the layers of the organization and at the level of one-to-one interactions.

Let’s imagine a team heading up a significant part of a global organization. The senior lead is someone who is extremely taskfocused, meticulous and detailed. He appreciates the people side, but is not naturally geared to think about the “human side” of business. He doesn’t share much about himself personally and doesn’t praise people for what they have done well (the assumption is that you are competent and know how good you are, so you don’t need to be told). The entire organization is task-focused, it’s important to be right and get it done, and at a time of significant change, people are fearful and risk averse. The best way for more junior people to get things done is to delegate upwards as the attention to detail and meticulous quality at the top will “catch” any errors. To shift the culture to one where each person is comfortable taking responsibility, working more creatively and “loosening” some of the fear, less risk-averse behaviour is needed to build the “humanity” – and that means supporting the senior leader to catch himself and to emphasize the people side at every opportunity until it becomes a personal habit and a pattern that is emulated throughout.

You look at a really big system and look down at a really tiny system and see the patterns, not identical, but similar being played out. What you do is important.

From this perspective, what are the patterns that you are creating around you?

WORKING WITHIN COMPLEXITY

Lesley Kuhn10 offers some ways of working using a complexity perspective which we apply directly here as an aid to consciously working with the complexity around you. We hope that in doing so, we have not taken liberties with Lesley’s original intentions.

First, rather than offer recipes or follow the recipes of others, generate your own carefully considered approaches, paying attention to what is happening around you and the quality of relationships at your fingertips.

Second, develop complexity “habits of thought”. Rather than forcing yourself to see linearity and cause and effect, notice the interactions, the chain of reactions that follows an event. Look for patterns in things. How are things self-organizing? Where are the self-catalytic loops that are generative, where are the negative dampening effects? What is generative in one space and dampening in another?

Third, be careful not to describe things as they “should be” rather than as they are. Pay attention to what really is happening now rather than what “should be” happening.

Fourth, value humility. No one idea is completely right – as history repeatedly shows. So be curious about how others can support an idea to emerge.

Taken together, these ways of working offer principles (not rigid rules) that can be self-resourcing, and prevent you from falling into the trap of seeing yourself as all-powerful, in control – a heroic leader. As a result, you are more able to see more clearly what might be happening around you. Being able to notice what is emerging is likely to give you some flexibility and nimbleness to navigate the systems you operate within – as well as catch yourself, before you inadvertently set off your own unintended butterfly effect.

COMPLEXITY AND 31PRACTICES

31Practices is not “the answer” to working with complexity, but it is a way to self-author and generate your own recipe for a successful organizational framework, bringing to life the organization values. 31Practices is in synergy with the idea of fractals, the natural interrelated world, that things are emergent and self-organized, and the self-catalytic loops.

The 31Practices methodology supports you to identify your purpose and vision and the principles or values that will enable you to work towards that vision. Each value translates into a set of daily Practices that is performed at a local, individual level and repeated across the organization – creating a visible pattern.

Different parts of the organization are involved in the design of the framework, and ultimately, each individual chooses “how” to live the Practice of the day – choosing what action to take that is linked to the Practice – while being mindful of the overall directional impact they are looking to have.

Once the 31Practices framework is created it is then enabled in organizational routines – allowing things to emerge, with built-in positive feedback loops as stories of behaviours and impact are shared. There are some embedded principles within 31Practices that may resonate with complexity thinking and be of significant, pragmatic use in organizations.

Want to know more?

Writings on complexity can be challenging reads. Among one of the seminal thinkers in this area was Gregory Bateson. If you are interested in reading his work (which is at the “for enthusiasts” end of the spectrum):

• Mind and Nature: A necessary unity (advances in systems theory, complexity and the human sciences). Hampton Press. The 2002 version is a reissue of this classic work.

• For a short introduction to his work there is a video clip on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AqiHJG2wtPI