Chapter 6:

24 fps versus Matchback

Before integrating a project with an NLE, a working frame rate must be determined. In the NTSC world, there are two: 24 fps and 30 fps. For PAL video, you’ll need to determine whether you’re going to work with Telecine A without pulldown, where the film is shot at 24 or 25 fps and is telecined at 25 fps; or with Telecine B, where the film is shot at 24 fps and is telecined at 24 fps with two fields of pulldown to equal 25 frames per second. If you choose to work at 30 fps or use Telecine B, you’re going to need software that can compute the matchback of your edits to the native film frame rate.

In this chapter, we’ll look at the differences between native 24 and 30 fps matchback projects as well as those PAL projects using pulldown versus speeded up transfer. We’ll examine some of the problems associated with each and also the advantages of working with them.

NTSC: 24 fps Projects

A true 24 fps project has a direct frame to frame correspondence with the film. There are no pulldown fields and therefore, what you see is what you get. NLEs and film software applications use one of two methods to create 24 fps projects.

They remove the pulldown fields during digitization.

They remove the pulldown fields after digitization.

Working at 24 fps can be problematic, especially if it’s not clear where the A frame is located. As discussed in Chapter 3, it is important that the telecine facility records the A frame on a :00 frame of a nondrop frame time coded videotape. Identification of the A frame is important to the software, because it will have to determine where the pulldown fields are located in order to ignore them. If the wrong frame is identified, the result will be a picture with jerky action, because the wrong two fields will be removed for each cycle of frames. For example, if the B frame was mistakenly identified to the NLE as an A frame, it would ignore the first field of frame 3 (which would be a D frame) and also ignore the last field of frame 5, which would be an A frame. The removal of these two fields would produce a jitter in any camera motion or action within the frame. If this mistake of misidentification is made, it’s necessary to unlink the media (on an Avid), delete it, and redigitize it with the proper frame identification.

There are some new products that have come along recently that depend on nondrop frame time code for proper identification. These video capture cards, which remove pulldown or perform a reverse telecine, use the time code to determine which pulldown fields to remove. As a result, they can ease some of the workload. However, if there are any anomalies in the telecine transfer, it goes back to the hard and tried way of manual identification and digitization. How well this digitization will go over with the film crowd remains to be seen.

When the telecine log is accurate and the numbers in the burn-ins match what is seen in the database, a 24 fps project is all but unbreakable. The great advantage is that there is frame-to-frame correspondence and no worries about adding or subtracting frames, as in matchback situations. Fast montages and flash cuts won’t pose a problem, because all of the key numbers are in the database.

NTSC Matchback

Matchback software programs were initially created to deal with projects created at 30 fps. More recently, some of these programs have added software-based reverse telecine and 24 fps capabilities. Newer video capture cards can remove pulldown and work in conjunction with matchback applications such as FilmLogic to create a true 24 fps cut list.

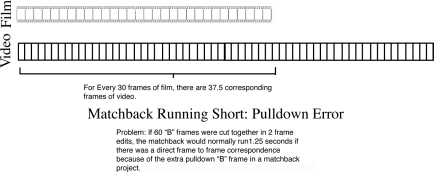

The problems associated with matchback are simple: there are two different frame rates, thus a single frame is added for every four frames from the original film, so the trouble is editing with pulled down frames. But pulldown isn’t the only consideration. Differences in frame rate can create problems of their own. The time base between the two mediums is different, so short edits will inevitably pose time base problems. Consider this: if several single frame edits are made using several A frames of a telecine transfer as a source, matchback will have to trim back the edit. The A frame is normally the start of a pulldown cycle. It consists of two fields, both with the same time code. So if 30 single-frame edits were made with A frames, 30 frames equals 1 second of video. But 30 frames equal 1.25 seconds of film. The matchback software will have to trim off six single-frame edits when creating a cut list for film to make the duration of the sequence correct.

Almost all matchback software makes adjustments from the tail of an edit, when an inaccuracy in duration is detected. In the case of these thirty single-frame edits, every fifth edit would be cut to maintain time consistency. This time base error is commonly referred to as matchback running long. Although it is uncommon, it can happen in a unique situation such as the one described in Figure 6.1.

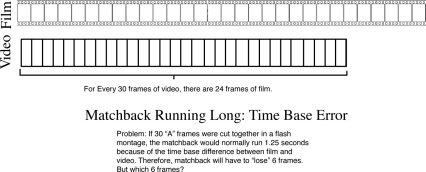

Figure 6.1 Matchback Running Long

Matchback software can also run short. Consider the same situation, except that instead of using A frames, use B frames. In a film transfer, the B frame lasts for three fields, covering the two fields of the second video frame and the first field of the third video frame in the pulldown cycle. So if 30 B frames were edited together as a 60-frame sequence, the matchback software would compute this as a 30 film frame edit, because the B frame consists of two different frames of video, but only one frame of film. Instead of listing 48 frames of film in the list, it would list 30 frames, or 1.25 seconds of film. As a result the matchback software must again determine how to create the same duration, this time by adding film frames. In this case, thirty film frames would be the equivalent of 1.25 seconds. An additional 18 frames of film would need to be added to the sequence in order to maintain time consistency.

Although these two examples are extreme, they illustrate why a matchback system can never be quite frame accurate. Matchback software will add or subtract a frame at the end of each edit to retain the proper duration of the film in proportion with the video. But because the editor cuts on a 30 fps system, matchback will occasionally have to adjust some edits, which could be a problem.

The way to avoid any frame issues when using matchback would be to cut in on an A frame and out on a D frame for every edit. Hardly a practical solution!

PAL 25 at 24 fps Projects (Telecine B)

PAL projects that are shot and transferred at 24 fps to PAL videotape require a single frame of pulldown to equal the 25 fps rate of PAL video. As discussed in Chapter 3, this is known as Telecine B. Telecine B does not work with all matchback applications, but Slingshot’s 24:25 preference allows for Telecine B, as does FilmLogic, which can match back the list accordingly.

The artifacts of matchback with Telecine B are less significant because of the lesser occurrence of pulldown. With NTSC matchback, there is a 50 percent chance that the last frame of a cut will need to be timed forward or backward, because of the four frames— A, B, C, and D —two of them contain a field of pulldown. With Telecine B, the occurrence of pulldown is less common. As a result, there is an 8 percent chance that pulldown could affect matchback with a PAL telecine B list.

If a model similar to NTSC’s frame count is used, the J frame would be the pulldown frame. As a result, if several J frames were edited together in the video, each representing two frames, matchback could again run short, as with NTSC.

Running long would be different however, because the maximum difference would be a miscount of 4.133 percent, the time base difference between 24 fps and 25 fps. For example, if any 50 single frames of PAL video were edited as single-frame cuts, only two frames would need to be cut to maintain time consistency. Although the problem is similar to that of NTSC, it is not nearly as disastrous and the fix is simpler.

1:1 PAL Frame Correspondence (Telecine A)

Although telecine A presents significant problems for editors with relation to the speeded up picture and sound, there is no need for matchback due to the fact that there is a 1:1 frame correspondence. But like the.01 percent pulldown issues associated with a 24fps NTSC project, there are going to be sound speed issues.

PAL Sound and Picture Digitized Together

Some software offers solutions that simplify the matter. For example, Avid’s Film Composer has solutions for 24 or 25 fps projects transferred at 24 fps with sound. For projects shot at 24 fps but digitized at 25 to create a 1:1 ratio, the film is digitized in the normal way and the Avid will slow it back down to its native 24 fps frame rate. There is no need to adjust any pulldown settings on the hardware. In fact, doing so would mess up the project. By selecting 24 fps as the project speed, the Avid knows that the film was shot at this rate and slows it down. This also slows down the audio transferred with the film, and the sampling rate will drop at the same 4.166 percent ratio. So, for a 44.1kHz sampling rate, the result is a 42.33kHz sample.

PAL Sound and Picture Digitized Separately

When picture and sound are digitized separately, the picture can be slowed down using Avid’s film settings preferences. Select a 24 fps speed and the film will slow down appropriately. Sound will be digitized and remain at production speed with no sampling issues. A digital cut can be performed with either pulldown inserted much like telecine B processes or with the picture and sound sped up 4.166 percent for a 1:1 frame ratio on the final video.

Telecine A can also be achieved with Final Cut Pro by slowing down the clips by 4.166 percent. This can be done for sound or picture and is easily attained. However, doing this will cause the time code numbers to increase according to the existing frame rate. A project telecined at 25 fps can be digitized and edited in that mode, then output it as a separate sequence with the time base adjusted. But you’ll want to duplicate the sequence for proper matchback prior to doing this.

A Final Note

The decision whether or not to use matchback versus 24 fps projects should depend on the support staff. If there aren’t enough eyes checking numbers, pulldown and sound speeds, a matchback would be more convenient. However, if a frame-to-frame correspondence between your media and the original film is required, 24 fps and telecine A are the only way to go.