Chapter 7

The Secrets of Successful Soldering

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Assembling your soldering toolkit

Assembling your soldering toolkit

![]() Soldering

Soldering

![]() Distinguishing a good solder joint from a not-so-good one

Distinguishing a good solder joint from a not-so-good one

![]() Undoing a bad solder joint

Undoing a bad solder joint

Soldering is one of the basic skills of building electronic projects. Although you can use solderless breadboards to build test versions of your circuits, sooner or later you’ll want to build permanent versions of your circuits. To do that, you need to know how to solder.

In this chapter, you learn the basics of soldering: how soldering works, what tools and equipment you need for soldering, and how to create the perfect solder joint. You also learn how to correct your mistakes when (not if) you make them.

Keep in mind throughout this chapter that soldering is a skill that takes a bit of practice to master. It’s not nearly as hard as playing the French horn, but soldering does have a learning curve. When you’re first getting started, you’ll feel like you’re all thumbs, and your solder joints may look less than perfect. But stick with it — with a little practice, you’ll get the hang of soldering in no time at all.

Understanding How Solder Works

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of making a solder joint, spend a few minutes thinking about what soldering is and what it isn’t.

Soldering refers to the process of joining two or more metal objects by heating them, and then applying solder to the joint. Solder is a soft metal made from a combination of tin and lead. When the solder melts, which happens at about 700 degrees Fahrenheit, it flows over the metals to be joined. When the solder cools, it locks the metals together in a connection.

Soldering is especially useful for electronics because not only does it create a strong physical connection between metals, but it also creates an excellent conductive path for electric current to flow from one conductor to another. This is because the solder itself is an excellent conductor. For example, you can create a reasonably good connection between two wires simply by stripping the insulation off the ends of each wire and twisting them together. However, current can flow through only the areas that are actually physically touching. Even when twisted tightly together, most of the surface area of the two wires won’t actually be touching. But when you solder them, the solder flows through and around the twists, filling any gaps while connecting the entire surface area of both wires.

Procuring What You Need to Solder

Before you can start soldering, you need to acquire some stuff, as described in the following sections.

Buying a soldering iron

A soldering iron — also called a soldering pencil — is the basic tool for soldering. Figure 7-1 shows a typical soldering iron.

FIGURE 7-1: A soldering iron.

Here are some things to look for when purchasing a soldering iron:

- The wattage rating should be between 20 and 50 watts. Note that the wattage doesn’t control how hot the soldering iron gets. Instead, it controls how fast it heats up and how fast it regains its normal operating temperature after completing each solder joint. (Each time you solder, the tip of the soldering iron cools a bit as it transfers its heat to the wires you’re joining and to the solder itself. A higher-wattage soldering iron can maintain a stable temperature longer while you’re soldering a connection and can reheat itself faster in between.)

- The tip should be replaceable. When you buy your soldering iron, buy a few extra tips so you’ll have replacements handy when you need them.

- Although you can buy a soldering iron by itself for under $10, I suggest you spend a few more dollars and buy a soldering station that includes an integrated stand. A good, secure place to rest your soldering iron when not in use is essential. Without a good stand, I guarantee that your workbench will soon be covered with unsightly burn marks. (The soldering iron pictured in Figure 7-1 includes a soldering station.)

-

A ground three-prong power plug is desirable, but not essential.

The grounding helps prevent static discharges that can damage some sensitive electronic components when you solder them.

- More expensive models have built-in temperature control. Although not necessary, temperature control is a nice feature if you’ll be doing a lot of soldering.

- Some models also have built-in static discharge. This can help eliminate the chance of damaging your circuit’s components while you’re soldering them.

Stocking up on solder

Solder, the soft metal that’s used to create solder joints, is an alloy of tin and lead. Most solders are 60 percent tin and 40 percent lead, but that ratio may vary a bit.

Although solder is wound on spools and looks like wire, it’s actually a thin hollow tube that has a thin core of rosin in the center. This rosin, called the flux, plays a crucial role in the soldering process. It has a slightly lower melting point than the tin/lead alloy, and so it melts just a few moments before the tin/lead mixture melts. The flux prepares the metals to be joined by cleaning and lubricating the surfaces to be joined.

Solder comes in various thicknesses, and you’ll need to have several different thicknesses on hand for different types of work. I suggest you start with three spools: 0.062 inch, 0.032 inch, and 0.020 inch. You’ll use the 0.032 inch for most work, but the thick stuff (0.062 inch) comes in handy for soldering larger stranded wires — and the fine solder (0.020 inch) is useful for delicate soldering jobs on small components.

You can purchase lead-free solder, although it’s considerably more expensive than regular solder made from lead and tin. However, lead-free solder is more difficult to work with than normal solder and is less reliable. If you’re concerned about the long-term effects of working with leaded solder, I suggest you switch to lead-free solder but only after you’ve become proficient at working with leaded solder.

Other goodies you need

Besides a soldering iron and solder, there are a few additional things you’ll need to have on hand for successful soldering. To wit:

- Third-hand tool or vise: It takes at least three hands to solder: one to hold the items you’re soldering, one to hold the soldering iron, and one to hold the solder. Unless you actually have three hands, you need to use a third-hand tool, a vise, or some other resourceful device to hold the items you’re soldering so you can wield the soldering iron and the solder. (Refer to Chapter 3 of this minibook for photographs of a third-hand tool and a hobby vise.)

- A sponge: Used to clean the tip of the soldering iron.

- Alligator clips: They serve two purposes when soldering. First, you can use an alligator clip as a clamp to hold a component in place while you solder it and, second, as a heat sink to avoid damaging a sensitive component when soldering the component’s leads. (A heat sink is simply a piece of metal attached to a heat-sensitive component that helps dissipate heat radiated by the component.)

-

Eye protection: Always wear eye protection when soldering. Sometimes hot solder pops and flies through the air. Your eye and melted solder aren’t a good mix.

Eye protection: Always wear eye protection when soldering. Sometimes hot solder pops and flies through the air. Your eye and melted solder aren’t a good mix. - Magnifying glass: Soldering is much easier if you do it through a magnifying glass so you can get a better look at your work. You can use a table-top magnifying glass, or a magnifying glass attached to a third-hand tool, or special magnifying goggles.

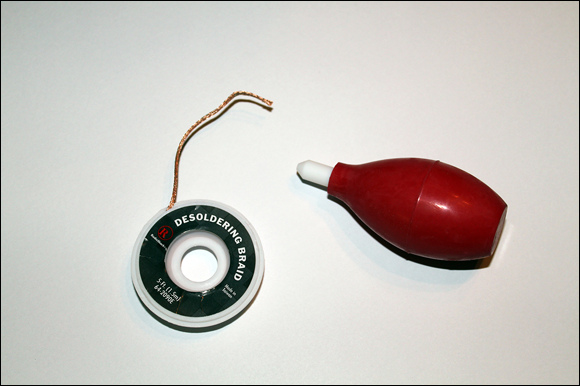

- Desoldering braid and desoldering bulb: These tools are used to undo soldered joints when necessary to correct mistakes. For more information, see the section “Desoldering” later in this chapter.

Preparing to Solder

Before you start soldering, you should first prepare your soldering iron by cleaning and tinning it. Follow these steps:

-

Turn on your soldering iron.

It will take about a minute to heat up.

-

When the iron is hot, clean the tip.

The best way to clean your soldering iron is to wipe the tip of the iron on a damp sponge. As you work, you should wipe the iron on the sponge frequently to keep the tip clean.

-

Tin the soldering iron.

Tinning refers to the process of applying a light coat of solder to the tip of the soldering iron. Tinning the tip of your soldering iron helps the solder flow more freely once it heats up. To tin your soldering iron, melt a small amount of solder on the end of the tip. Then, wipe the tip dry with your sponge.

Soldering a Solid Solder Joint

The most common form of soldering when creating electronic projects is soldering component leads to copper pads on the back of a printed circuit board. If you can do that, you’ll have no trouble with other types of soldering, such as soldering two wires together or soldering a wire to a switch terminal.

The following steps outline the procedure for soldering a component lead to a PC board:

-

Pass the component leads through the correct holes.

Check the circuit diagram carefully to be sure you have installed the component in the correct location. If the component is polarized (such as a diode or an integrated circuit), verify that the component is oriented correctly. You don’t want to solder it in backward.

-

Secure the component to the circuit board.

If the component is near the edge of the board, the easiest way to secure it is with an alligator clip. You can also secure the component with a bit of tape.

-

Clamp the circuit board in place with your third-hand tool or vise.

Orient the board so that the copper-plated side is up. If you’re using a magnifying glass, position the board under the glass.

-

Make sure you have adequate light.

If you have a desktop lamp, adjust it now so that it shines directly on the connection to be soldered.

-

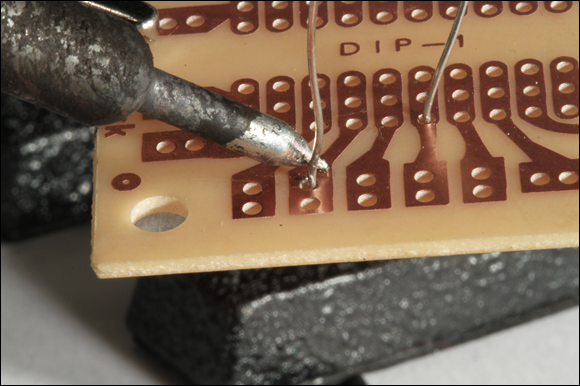

Touch the tip of the soldering iron to both the pad and the lead at the same time.

It’s important that you touch the tip of the soldering iron to both the copper pad and the wire lead. The idea is to heat them both so that solder will flow and adhere to both.

The easiest way to achieve the correct contact is to use the tip of the soldering iron to press the lead against the edge of the hole, as shown in Figure 7-2.

-

Let the lead and the pad heat up for a moment.

It should take only a few seconds for the lead and the pad to heat up sufficiently.

-

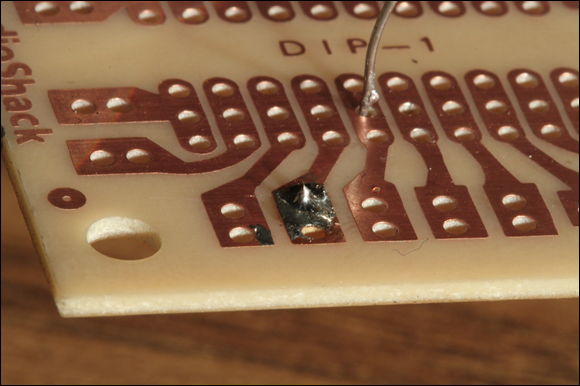

Apply the solder.

Apply the solder to the lead on the opposite side of the tip of the soldering iron, just above the copper pad. The solder should begin to melt almost immediately.

Figure 7-3 shows the correct way to apply the solder.

Do not touch the solder directly to the soldering iron. If you do, the solder will melt immediately, and you may end up with an unstable connection, often called a cold joint, where the solder doesn’t properly fuse itself to the copper pad or the wire lead.

Do not touch the solder directly to the soldering iron. If you do, the solder will melt immediately, and you may end up with an unstable connection, often called a cold joint, where the solder doesn’t properly fuse itself to the copper pad or the wire lead. -

When the solder begins to melt, feed just enough solder to cover the pad.

As the solder melts, it will flow down the lead and then spread out onto the pad. You want to feed just enough solder to completely cover the pad, but not enough to create a big glob on top of the pad.

Be stingy when applying solder. It’s more common to have too much solder than too little, and it’s a lot easier to add a little solder later if you didn’t get quite enough coverage than it is to remove solder if you applied too much.

Be stingy when applying solder. It’s more common to have too much solder than too little, and it’s a lot easier to add a little solder later if you didn’t get quite enough coverage than it is to remove solder if you applied too much. -

Remove the solder and soldering iron and let the solder cool.

Be patient — it will take a few seconds for the solder to cool. Don’t move anything while the joint is cooling. If you inadvertently move the lead, you’ll create an unstable cold joint that will have to be resoldered.

-

Trim the excess lead by snipping it with wire cutters just above the top of the solder joint.

Use a small pair of wire cutters so you can trim it close to the joint.

FIGURE 7-2: Positioning the soldering iron.

FIGURE 7-3: Applying the solder.

Checking Your Work

After you’ve completed a solder joint, you should inspect it to make sure the joint is good. Look at it under a magnifying glass, and gently wiggle the component to see if the joint is stable. A good solder joint should be shiny and fill but not overflow the pad, as shown in Figure 7-4.

FIGURE 7-4: A good solder joint.

Nearly all bad solder joints are caused by one of three things: not allowing the wire and pad to heat sufficiently, applying too much solder, or melting the solder with the soldering iron instead of with the wire lead. Here are some indications of a bad solder joint:

- The pad and lead aren’t completely covered with solder, enabling you to see through one side of the hole through which the lead passes. Either you didn’t apply quite enough solder, or the pad wasn’t quite hot enough to accept the solder.

- The lead is loose in the hole or the solder isn’t firmly attached to the pad. One possible reason for this is that you moved the lead before the solder had completely cooled.

- The solder isn’t shiny. Shiny solder indicates solder that heated, flowed, and then cooled properly. If the solder gets just barely hot enough to melt, then flows over a wire or pad that isn’t heated sufficiently, it will be dull when it cools. (Unfortunately, the new lead-free solder almost always cools dull, so it looks like a bad solder joint even when the joint is good!)

- Solder overflows the pad and touches an adjacent pad. This can happen if you apply too much solder. It can also happen if the pad didn’t get hot enough to accept the solder, which can cause the solder to flow off the pad and onto an adjacent pad. If solder spills over from one pad to an adjacent pad, your circuit may not work right.

Desoldering

Desoldering refers to the process of undoing a soldered joint. You may have to do this if you discover that a solder joint is less than satisfactory, if a component fails, or if you connect your circuit incorrectly.

To desolder a solder connection, you need a desoldering bulb and a desoldering braid. Figure 7-5 shows these tools.

FIGURE 7-5: A desoldering bulb and a desoldering braid.

Here are the steps for undoing a solder joint:

-

Apply the hot soldering iron to the joint you need to remove.

Give it a second for the solder to melt.

-

Squeeze the desoldering bulb to expel the air it contains, and then touch the tip of the desoldering bulb to the molten solder joint and release the bulb.

As the bulb expands, it will suck the solder off the joint and into the bulb.

-

If the desoldering bulb didn’t completely free the lead, apply heat again and touch the remaining molten solder with the desoldering braid.

The desoldering braid is specially designed to draw solder up much like a candle wick draws up wax.

-

Use needle-nose pliers or tweezers to remove the lead.

Do not try to remove the lead with your fingers after you have desoldered the connection. The lead will remain hot for awhile after you have desoldered it.

Do not try to remove the lead with your fingers after you have desoldered the connection. The lead will remain hot for awhile after you have desoldered it.