Experience the Service

Emily has just attended a team training session on a new thing called ‘Service Design’. Emily loves this new customer-focused approach and how it enables her to look at their business through the customers’ eyes. Using journey maps showing the whole context of the customer’s experience, she could better see why customers might think about using their services and what happens during and after the customers have transacted with the business.

Emily already knew that the various business functions in her organization act as if they are pretty much separate entities that perform their piece of a process. There was never much communication between these silos. No wonder customers fell through the cracks from time to time and experienced prolonged and frustrating interactions with several different teams while conducting a transaction.

Emily enjoyed learning how Service Design could help the silos in her organization to come together by focusing on a shared understanding of the customer journey and redesigning the journey to be more efficient and effective for the customer.

The attendees at the workshop spent a large part of the time jointly discussing the customer journey and building up the journey map with sticky notes on the wall. This was a useful way to get everyone involved in developing the customer journey collaboratively. Then they went further and added the interactions and transactions that occur at each touchpoint of the customer journey, building up detail as they explored the journey more. There were a lot of stickies on the wall by the end of the session.

All these efforts resulted in what the facilitator called a ‘service blueprint’ that provided a central reference for all the teams to apply in their improvement efforts. The blueprint seemed to Emily to be a simple and understandable map of a customer journey. She thought the service blueprint could be helpful in keeping people focused on the viewpoint of the customer, rather than their own internal viewpoint. For the customer journey that the workshop addressed, the service blueprint contained several touchpoints between customers and the business. Sometimes a touchpoint was a simple interaction or exchange of information, but at other points, the customer transacted with the business – that is, they were exchanging value.

Service Design seems like it could help the team to design better services and ensure that customers have a better experience. But Emily is confused about how Service Design could bring about a better design of each individual transaction – that is, a blueprint that can be used directly to communicate system requirements and process workflows. She thinks that the service blueprint doesn’t go deep enough into the details. Although it is clearly a useful tool, Emily worries that her IT colleagues will find Service Design somewhat superficial; as such, it does not provide them with the requirements detail that they need.

While Service Design greatly helps to envision the desired customer experience and the way customers interact and transact with the business, it only goes so far. Service Design emphasizes the customer perspective more than the internal perspective. You still need to consider the internal processing needs and to specify the implementation details that will come together to make the service blueprint real.

Without this level of detail, the implementation project may lose something of the essence of the excellent Service Design work that has gone before it. The customer perspective is diminished, or perhaps the internal process journey is implemented in a clumsy manner that is little improvement on the old process. If either of these things occurs, then the supposed benefits of an improved customer experience, or of digitizing a service, will be lost.

The Transaction Pattern that we outlined in Chapter 3 corrects this imbalance and complements Service Design. How does the Transaction Pattern tie in with a service blueprint, and how could Emily and her team use both methods alongside each other?

The Service Design approach

Your car mechanic offers services such as regular servicing. They may be good at their work and do an excellent job – this is the quality of their work. However, your mechanic may keep you waiting for weeks for an appointment, or fail to have the car ready when they promised, or be rude in their responses to your questions – this is the quality of your experience. You are more likely to go back to a mechanic that minimizes the disappointments and emotional upsets of getting your car serviced, provided of course that the quality of their work is just as good.

So, the quality of the experience that the customer has is an important extra dimension of a service. Businesses that want to facilitate a pleasant, productive, or effective experience for their customers will pay considerable attention to the customer experience and what emotions are engendered, as much as the services themselves. To enable this focus on customer experience, practitioners have developed an approach called ‘Service Design’.

Service Design is a new approach to designing business services emphasizing the customer’s viewpoint. The approach recognizes that as well as designing the business’s products (tangible things like cars and appliances, as well as financial products, contracts, and so on), the business should also design the service and the desired experience that accompany a product. Businesses that fail to recognize this, usually offer a terrible experience to their customers. For example, two shops may sell identical products, but the customer’s experience of the shops’ service may be vastly different. The differing experience of the retail services is a key factor in which shop the customer chooses to buy from.

The development of the Service Design approach is a response to important trends in the early 21st Century. These social, economic, and technological trends are creating pressures on businesses to operate differently than how they have in the past. Customers are expecting better service, including through convenient digital channels. As we explored in the Introduction, these trends demand that established businesses adopt new operating models. Not only does the customer experience need to be modified and streamlined, but the whole modus operandi of the business needs to change to align with the desired customer experience. A new operating model does not simply evolve but must be designed. Service Design offers a method for approaching the problem, by ensuring that a focus on the customer is front and center of the new model.

Service Design takes a ‘big picture’ view of the journeys that customers engage in. These journeys involve various touchpoints between the customer and the business, at which the customer obtains information from, or interacts and transacts with, the business or government service.

Service Design offers a variety of tools that can be used in combination to design a service. Developing customer profiles and interviewing to obtain customer insights are used to gain information about the experience that customers have within their context. This information is then used to create customer journey maps, which visualize the touchpoints that customers have with the business, through selected channels, at different phases from becoming aware of a service, to joining and using the service, through to leaving the service. Customer journey maps often include notes about how a typical customer might feel at each touchpoint. Customer journeys are an illustration of the experience that a customer has.

There is a wide and rich variety in the styles of customer journey map, from the simple and general, to the detailed and specific journey that a real person (in the form of a persona) undertakes. Figure 4-1 is a template for a less complex journey map, while a more complex example is shown in Figure 4-2. The key is to select a style that is appropriate for your context and what insights you want to gain from the map. Many creative designers have made graphically complex customer journey maps that seek to engage the viewer while conveying a lot of information. An internet search for “Customer journey map example” will return hundreds of examples; examining them may help you identify a good style to use in a particular instance.

Typically, a customer journey map depicts the journey horizontally as a sequence of stages. Each stage is subdivided into the steps or activities that the customer performs. Some activities will involve a touchpoint with the business, but many will not. These latter activities serve to remind the service designers of the customer’s context including what other tasks they might perform while transacting with the business.

Various vertical layers are added to each stage of the journey, such as what the customer is thinking and feeling, the channels used for each touchpoint, and insights gained through user research about opportunities to improve the customer experience. The thinking and feeling layers attempt to portray the customer’s thoughts at each stage and their emotional response – e.g. whether they are happy with the experience or frustrated by it. The emotional responses are often shown graphically to represent the ups and downs of the customer’s feeling.

A customer journey map can then be used to delve into the detail at each touchpoint to redesign it for a better experience. In contrast to business process maps, which are internally oriented, a customer journey map shows what customers do and their interactions with the business, not what happens behind the façade of the touchpoints.

Figure 4-2 An example of a customer journey map9

Customer profiles and insights can be generalized or fictionalized in the form of personas and service scenarios. Each service scenario features a clearly defined context, customers, staff, brands, and motivations. Scenarios are most useful for trying out different future state service designs, by testing them against a few ‘real’ scenarios. This is an effective way to assess whether a new design is an improvement for a range of customer types and contexts. The new service blueprint can be tweaked on the fly to suit each service scenario better. This is a very low-cost way to settle on an improved service design.

Another Service Design tool is called ‘organizational impact analysis’. This is a tool for examining the effect of a customer-facing change on the internal operations of the business. It asks: What do we need to change internally to deliver this improved customer experience – which business processes, procedures, team structures, systems and databases? How significant are these changes? How much effort will the change require to realize the new experience? Understanding the extent and complexity of this impact of change is critical to implementing a change successfully. Service Design assesses change impact by drawing connections between the customer experience and the service delivery functions and capabilities. This helps with defining which functional units, business capabilities, processes, and policies will need to be updated. Furthermore, by aligning these change impacts to the customer journey, it is clear which touchpoints will be affected if an impact is only partially implemented, or not at all.

Finally, a key tool of the Service Design approach is design workshops. Workshops are highly collaborative and creative exercises, in which participants engage actively. Templates are used to structure the conversation and to capture the insights. Design workshops are used at multiple points throughout a change initiative, but the focus of each workshop will vary. It is important that design workshops are not simply a one-off event, but a series of events that bring people together regularly. This ensures that a common vision is shared, while enabling the design of the service to evolve as understanding is enhanced and complexities are exposed.

The focus of a workshop may be to understand a situation or a problem, to capture and share what is known about customers’ current experience and problems with using a service that needs improvement. Also, this workshop style can be used to identify unmet needs and gaps in the current service offering that present an opportunity for innovation. Another workshop style is to imagine new concepts for improvements that could be made to services. Service scenarios are often developed in this style of workshop, bringing ideas to life. This enables new ideas to be evaluated against the customer scenarios that are likely to be encountered when the improved or new service is operational. The third style of workshop is to design a detailed view of a service blueprint based on a new concept.

These design workshops develop front office and back office views of the proposed service, working across channels and business functions. The result is a comprehensive map of the service that provides a shared understanding to all teams involved in building or operating the service. Workshops may also be used to govern the build of multiple project components to maintain alignment with a consistent customer experience and goals. No matter the focus of a workshop, all workshops bring together multidisciplinary teams who contribute their individual perspectives to a common shared vision.

A proposed service design is mapped in the form of a service blueprint that visualizes the customer journey alongside the channels and front office actions that customers will engage with at each touchpoint. Service blueprinting techniques have been studied and formalized to an extent, but they do not need to use complex notations; blueprints can be expressed using simple and easily understood graphics.

The service blueprint, like the customer journey map, is anchored on a horizontal sequence of customer activities. The customer’s viewpoint of their journey drives everything else. Aligned with each of the customer activities there are actions taken by front office employees. These actions may vary according to the channel that is used for the interaction (face-to-face, phone, email, or website). Beneath the front office actions are the supporting activities that occur in the back office that customers do not interact with directly. A line of visibility should be added to the blueprint to draw attention to what customers are aware of and what is invisible to them. Finally, the documents, websites, vouchers, and other artifacts that customers receive or provide at each touchpoint (often referred to as ‘physical evidence’) are noted on the blueprint. The diagram in Figure 4-3 shows an example service blueprint.

The service blueprint can be extended to include the organizational functions that perform work behind the scenes and in supporting roles. Also, the business capabilities that are required to deliver the service can be included in the blueprint. Furthermore, operational measures and other factors can be added to the blueprint. These might include timing of activities or the minimum timeframe that customers expect, any existing failure points, and points at which excessive waits occur.

Figure 4-4 is an example of a service blueprint that shows how the organizational functions are aligned with each of the steps in the customer journey.

Service Design takes a broad view of what a service is. Services comprise many information exchanges, transactions, and other interactions across a customer journey. The service blueprint shown in Figure 4-4 includes an information service (providing information about insurance policies) and two transactional services (buying the policy and making a claim). In addition, Customer Support facilitates several interactions that help to move along the information and transactional services.

Take a telephone company for instance. The products offered by a telecommunications company include fixed line telephone, mobile phone, and broadband internet products. When a customer explores, buys, and uses a fixed line telephone product, the company will give them information about the product, possibly at multiple points in the journey. The customer will interact with the business through various channels (e.g. retail shop, phone, and online) and they will transact with the business in several different ways. The transactions include the initial purchase and contract signing, paying monthly bills, setting up the product in the home, addressing faults and other technical issues, and eventually withdrawing from using the product.

Each time the customer transacts with the telephone company a separate transaction occurs. Each transaction, from its initiation by the customer to the response by the company, will follow the Transaction Pattern described in this book. Therefore, the Transaction Pattern applies at a more specific and detailed level than the service blueprint.

A service blueprint sets the context for transaction design

Service Design’s customer focus contributes a perspective that is often missing from projects tasked with redesigning business processes or developing enhancements to information systems. This aspect alone means that significant value can be gained from the Service Design approach. Using service blueprints enables the surrounding context of each transaction to be readily shared and understood by everyone involved in a project, even when the project’s scope is limited to one transaction type among several in the customer journey.

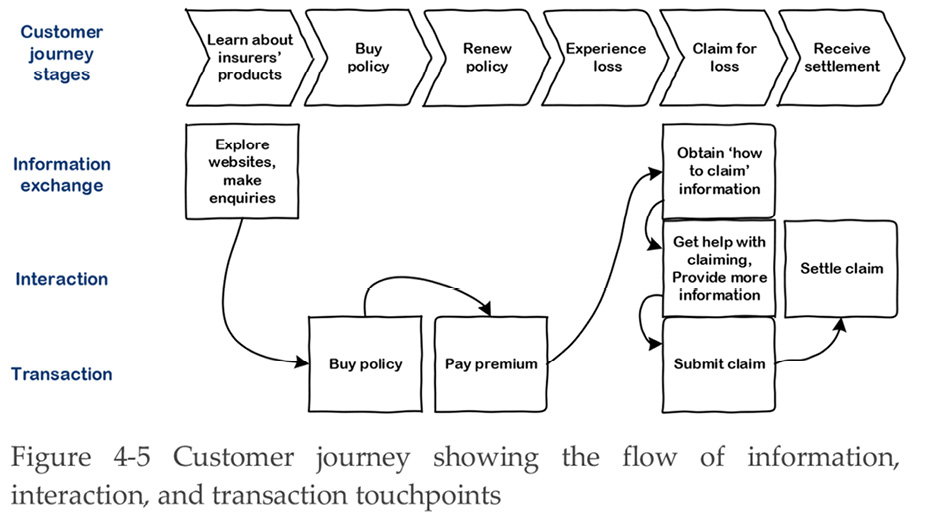

A service blueprint highlights the point where the customer transacts. Certain touchpoints in the customer journey are the points at which transactions start or finish. Using these touchpoints as markers, the blueprint can be segmented into distinct transactions. Information exchanges and other interactions occur between the transacting touchpoints. An alternative style of a service blueprint that shows this clearly is a simple expression of a customer journey, aligned to three separate rows showing the information services, transactions, and other interactions that the customer engages in at each touchpoint of the journey. This is a straightforward way to understand and communicate two very important pieces of information: the point where the customer seeks information or interacts through a channel, and the point where the customer initiates or completes a transaction with the business. This style of service blueprint is illustrated in Figure 4-5.

This technique allows us to home in on one transaction that needs improvement, while being aware of the context in which it is used by the customer and the internal actions and capabilities that support the transaction. This is a useful perspective to keep at the forefront of the subsequent design and development work.

The thorough understanding obtained from the service blueprint is an excellent foundation for subsequent detailed system and process design work. A service blueprint, however, is not enough to begin development of the systems needed to implement the blueprint. If it were used in that way, the business and functional requirements of the system would be elaborated through user stories using an Agile development approach. This is a common approach, but it has a significant disadvantage because it lacks architectural underpinnings. Although the user stories may be entirely consistent with the service blueprint, they are isolated features that are difficult to align to a coherent architecture of the full business solution. It is like building part of a house with some knowledge of how that room will be used, but no knowledge of the overall architecture of the house. Awareness of the full architecture ensures that the house has integrity and functions well as a whole. The risk of going into software development armed with a service blueprint and user stories alone is that the business solution solves an immediate problem but creates systems and data structures that lack integrity. This can lead to downstream problems. Subsequent remediation exercises to fix these issues are inevitable in time.

Since Service Design focuses largely on a customer-needs, outside-in perspective, the approach can only make a limited contribution to the detailed specification of how transactions are initiated and processed. By ‘detailed specification’, we are referring to the precise data requirements, business rules, and workflows that enable a transaction to be received and processed efficiently (with minimal cost and time) and effectively (the customer achieves their objective and the policy is complied with). On the other hand, Service Design and the Transaction Pattern are highly complementary. The products of the Service Design approach can be used alongside the Transaction Pattern described in this book to deliver a coherent and comprehensive specification. Detailed transaction design builds on the foundation of the higher-level Service Design activities. Combining these two methods makes for a highly effective design process that results in a design that has a strong customer focus while also giving structure to the detail that is required for implementation.

Service Design points to how the customer experience of a service can be streamlined to fulfil the customer’s objective more efficiently, through better exchanges of information, more effective interactions, and smoother transactions. This results in a service blueprint that provides a strong foundation for more detailed design work. Following on from the Service Design activities, the Transaction Pattern will support you in going to the next level of design. The Transaction Pattern provides a framework to specify the necessary data, business rules and workflow that govern the business operations for each type of transaction. Requirements definition workshops can be structured on templates derived from the Transaction Pattern and conducted in a similar way to the Service Design workshops. (In Chapter 9, we suggest how transaction requirements workshops can be managed in such a structured fashion.)

Developing this level of design detail is only necessary when the need for change, either in systems or processes, has been identified, perhaps through the Service Design work or through strategic investment planning. It may not be necessary to specify the detailed design of all transactions in a blueprint all at once. Indeed, trying to do too much at once raises the overall risk of project failure. Each transaction can be specified, built, and implemented independently. The result will be one or more transaction designs, each based on the request-and-response pattern, that can then be implemented into systems and business operations. Each transaction is employed at the appropriate touchpoint in the service blueprint that was agreed upon earlier during the Service Design work.

The complexity that is often inherent in sophisticated business systems and processes will become more manageable using this two-fold approach. The specification of each transaction will be laid out in a coherently structured end-to-end design yet separated from the specification of other transactions. The service blueprint holds the separate transactions together, by providing an easily understood customer-centric map showing the full context of each individual transaction.

Identifying transactions

We have seen in this chapter how a customer’s journey may comprise many transactions and information exchanges. To understand the customer journey fully, we need to partition it into these separate services, so that we know where one transaction starts and finishes. Such analysis of a customer journey can sometimes prove to be difficult, as a transaction may be spread over several touchpoints, or two transactions might be muddled together in one touchpoint. Two techniques may be helpful to clearly distinguish one transaction from another: Looking for activities that change master data, and mapping value streams. Let’s investigate each of these tools.

Tool #1: Follow the master data

A transaction will usually create or update only one type of master data. In the Apply for license example in Chapter 2, the master data being created is a Driver license record. On the other hand, if the service user does not provide any data to the business, then the service is almost certainly an information service – there is only a one-way exchange of information. Each touchpoint in a customer journey has a unique purpose, with information passing between the customer and the business. The key to marking the beginning and end of a transaction is to figure out whether any master data is altered at each touchpoint of the customer journey. Oftentimes, a touchpoint will be an interaction that is needed to move the transaction along, such as a request for more information, a progress notification, or a status update. Other touchpoints will clearly commence a new transaction or complete a transaction. These kinds of touchpoints are useful markers for dividing a journey into discrete services.

Tool #2: Value stream mapping

The flow of information exchanges and transactions shown in Figure 4-5 corresponds to the services offered by the business. When these services are arranged in a linear series, we can see that each service delivers some value to the customer and adds to the value delivered by the previous services. This series of value-delivering services is called a ‘value stream’. A value stream represents clearly and concisely what the organization is in business to do, what value it delivers to its customers – that is, the business’s value proposition. Unlike a customer journey map and service blueprint, a value stream is usually expressed with an internal perspective, rather than a customer perspective. They are diagrammed as a simple map, such as the map shown Figure 4-6 for credit card services.

This example also indicates the value that customers derive from each service in the series and the overall value proposition.

While the content of the value stream map bears a close resemblance to the customer journey map, they are not the same. Figure 4-7 shows a customer journey map for obtaining and using a credit card.

You will note that the active verbs used in the value stream in this example (Market, Establish, Process, Bill, and Cancel) show a perspective that is internal to the credit card provider. On the other hand, the verbs used in the steps of the customer journey (Learn, Apply, Receive, Use, Repay, and Close) portray the customer’s perspective. That is, the two sets of verbs mirror each other. This is no accident and reflects the close relationship between the customer journey, in which the focus is on the customer’s experience, and the more business-like value stream with its internal perspective.

The activities in the customer journey should align closely with the services in the value stream map. This alignment is illustrated in Figure 4-8. Using this alignment, we can then identify whether each service in the value stream map is a transaction or provides information only. In this case, we can identify an information service by which customers learn about the bank’s credit card products, and three transactional services, as follows:

- Processing a new credit card application

- Billing each month for purchases and interest charges

- Cancelling a credit card account.

The Transaction Pattern is used to specify and implement each of the transactions.

In this way we can build up a complete picture of the customer journey, the transactions the customers use at various points, and the value that they receive. By analyzing the alignment of the customer journey with the value stream, we can not only improve the journey map itself, but also identify every transaction and information service that exists in the business. Using a diagram such as this during a process improvement initiative or system redevelopment project enables people to retain a strong awareness of the business context of a transaction or of a component of a transaction. The map allows the reader to rapidly orient themselves to the business context, so they are aware of where the current topic of discussion fits in the entire journey.

In Figure 4-8 we can see that the customer journey, the transactions and information services, and the Transaction Pattern unite to deliver the desired customer experience and value. This alignment means that the customer perspective is always present when it comes to specifying the business requirements for a transaction when using the Transaction Pattern. So far, such as in Figure 4-7 and Figure 4-8, we have seen how a value stream map illustrates a high-level picture of the value stream, which is useful for obtaining a rapid overview. However, to be useful as an input to projects more detail is required. We need to describe each service of the value stream in a less-ambiguous manner than a mere label such as ‘Establish new credit card’. Also, we need to understand more precisely what each service produces and what stakeholders are involved.

Fortunately, there is a formalized, structured way to express a value stream in more detail, including: what triggers it, what occurs within it, and what is produced by each service of a value stream. Each service is given a name and description, entrance and exit criteria, the item of value that is produced, and the external and internal stakeholders who are involved.10

For example, the bank’s value stream illustrated in Figure 4-6 is called Credit Card Services and the value proposition is: Readily accessible credit for purchases (i.e. the value that the customer would expect from using the services). As shown above, there are five services, or ‘value stages’, in this value stream. One of these services – Establish new credit card account – is defined formally as ‘Receiving an application, validating, approving, issuing, and activating a new credit card’. The stakeholders involved are the customer and the bank’s front office staff, Card Services, Card Production & Dispatch. The entrance criterion is that the application for a credit card is initiated, while the exit criterion is that the new credit card has been issued and activated by the bank. The value to the customer is that they know that they now have preapproved credit up to a certain limit to buy goods and services. In a similar fashion, the remaining stages of the Credit Card Services value stream are defined, as shown in Table 4-1. (The table can be used as a template for this purpose when formally describing any value stream.)

The structure described above to fully define a value stream imposes a discipline that prevents some types of errors. For example, if you cannot define the value that the customer receives from a service in the value stream, then you have most likely identified only part of a service – you have broken down the value stream too much.

Take it up a level until you can clearly define the entrance and exit criteria and the value achieved for the customer. For example, a step that only validates the customer’s address is unlikely to deliver any value to the customer (they already know their address), so the service must do more. The right level is reached when you can clearly see a request followed by a response that delivers the value sought by the customer.

In the next chapter we look at some concepts from business architecture and how these can help to bring greater elegance and integrity to your work on a specific transaction. In Chapter 9 we suggest a method for discovering and documenting requirements for a transaction. The method utilizes an interactive workshop style similar to Service Design techniques.

Three key points from this chapter

- Service Design has a lot to contribute to improving services, systems and processes, by emphasizing the customer perspective.

- A Value Stream provides a mirror to a service blueprint through documenting the internal perspective and objectives of a set of business services.

- The Transaction Pattern complements both Service Design and Value Stream Mapping, by taking a specific transaction to a deeper level of detail while retaining clear sight of both the customer perspective and the internal perspective.

Further reading

Mager, Birgit. (2018) Introduction to Service Design - What is Service Design? Retrieved from: youtu.be/f5oP_RlU91g.

Reason, Ben; Løvlie, Lavrans and Flu, Melvin Brand. (2016) “Service Design for Business”. Wiley.

Service Blueprint in Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Service_blueprint.

A key to service innovation: Services blueprinting; W.P. Carey School of Business, Arizona State University. Retrieved from https://bit.ly/2BKSrr3.