Executing Processes in the Global Environment

There are 10 processes allocated to the executing process group. How each process is managed will differ based upon the project scale, geography, language, and culture. The project team must be prepared to answer questions that are certain to arise when considering how to execute the plan in the global environment. A table of executing processes along with questions to be answered so that the execution of the project is supported is provided in Table 2.1 (Project Management Institute 2017).

Table 2.1 Global project questions in the Executing process group

|

Processes within the executing process group |

Global project questions to be answered |

|

Direct and manage project work |

What kind of oversight and supervision of project work carried out in geographically distant locations is required? How will project work be assigned to geographically dispersed teams? |

|

Manage project knowledge |

How will lessons learned be captured and organized from geographically distributed operations? What standards will be used for language, document formatting, nomenclature, and storage of information? |

|

Manage quality |

What quality standards will the project employ? How will quality be assured and controlled as components and subassemblies from remote operations are integrated? Who will manage and make decisions regarding the quality of project deliverables? |

|

Acquire resources Develop team Manage team |

From where will resources be obtained? What language-, cultural-, or distance-related factors should be considered when building, training, and supervising geographically distributed teams? How will virtual teams be managed? |

|

Manage communications |

What language and cultural considerations must be considered in the choice of media, location, frequency, and language of information exchange? |

|

Implement risk responses |

How are global risk plans triggered and managed once risks become issues? |

|

Conduct procurements |

From where we will source labor, hardware, and software components, and capital equipment in geographically distant locations? How do we ensure the performance of remote vendors? Who authorizes procurements in remote locations? What legal jurisdiction will govern globally distributed contracts? |

|

Manage stakeholder engagement |

What special measures must be considered for conducting meetings, project reviews, and negotiations given the impact of language, culture, and distance? |

Each of the issues raised in the walk-through of execution processes can be distilled into concerns about distance, trust, culture, and the global legal and regulatory environment.

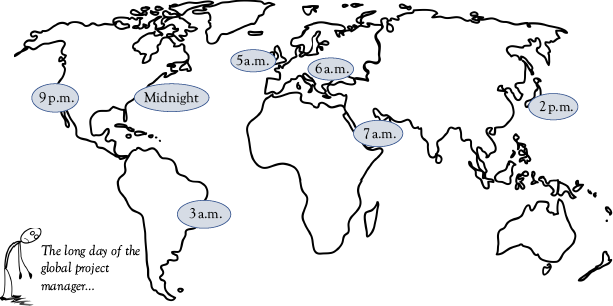

Distance and Time Lag

A project that is global in scope usually involves globally distributed teams and more likely than not virtual teams. This arrangement takes away the intimacy and intensity of day-to-day face-to-face interaction that normally occurs when teams are co-located in the same venue. Even though jet travel and modern telecommunications lower the effective distance, the distance reveals itself in the time lag required for physical interaction, the differences in time zones, and finally, the implications on trust between team members. The time lag between locations has a tangible impact on project team members. To provide an example, assume that a project manager is based on the east coast of the United States. When this project manager is arriving at work, teams in Europe are going to lunch, whereas teams in Asia, if not still in the office, are at home or having dinner. Later in the evening on the east coast, the project manager may have a late-night conference call with Asian teams. The daily work of the project manager is therefore “bookended” by early morning and late-night conference calls with geographically distributed teams. A global project manager could therefore be thought of as having a never-ending “round-the-clock” job. The time effect created by distance also has significant implications for travel to face-to-face meetings. When the same project manager on the east coast of the United States travels to continental Europe for meetings, the flight will typically leave in the evening, cross the Atlantic through an unusually short evening, followed by a morning arrival. The first day unfolds as an ongoing battle to remain awake given the time shift and the short evening. Given the grind of the first day of jet lag, it is usually not difficult to fall asleep. However, when the alarm goes off at 6 a.m. the following morning, the project manager’s watch will indicate midnight. Waking up at this hour can be a daunting prospect. The project manager going into an important decision-making meeting should be aware that he or she may not be capable of clear thinking or communications. It is easy to make mistakes in such a situation (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 The long day of the project manager

On the other hand, when an east coast project manager travels to Asia for meetings, flying over is like a very long day. The plane follows the sun across the Pacific Ocean and lands in the afternoon. It is not unusual for project managers to wake up fully refreshed around 4 to 5 a.m. the next morning. The feeling is like staying up all night and sleeping throughout the following day. What implications exist for traveling east versus west for important project meetings? It is generally easier to attend an important morning meeting overseas when traveling west than it is when traveling east. If you have an important project negotiation meeting approaching and you have a choice of venue, prefer to go west.

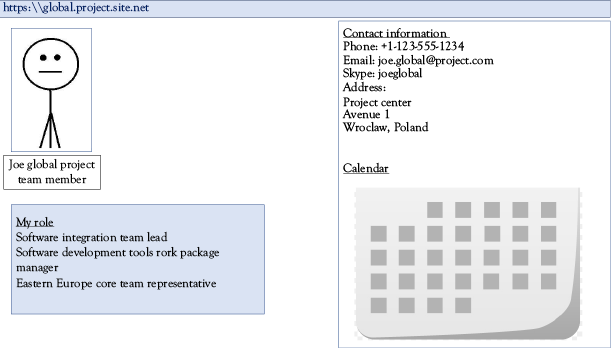

Intranet and Calendar

The fact that the project operates across large geographical distances makes it implicit that many of the teams working on the project will be virtual teams. Virtual team members do not usually interact with each other on a day-to-day basis. It is important then for the project manager to ensure that team members are familiar with the names of each team member, where they are located, their contact information, and finally, the time zones they inhabit. As a suggestion, creating intranet page for the project team and subpages for every localized project team around the world would foster familiarity and trust between globally distributed team members (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Intranet pages for project teams and team members

It is further recommended that information about every team member be published on the site and include with this project team a calendar that provides the current time in every project location. This aids in the coordination of conference calls and as well duly noting holidays and vacation periods to minimize confusion and inconvenience.

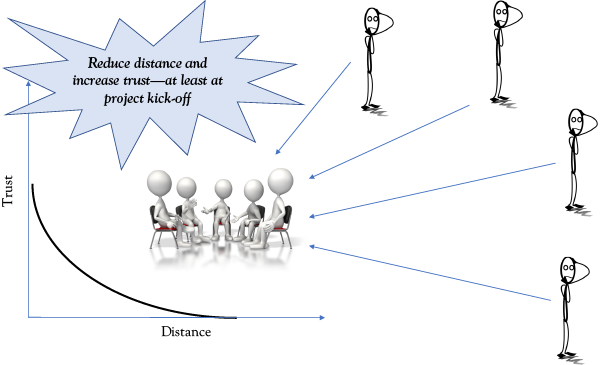

Distance and Trust

It is easier to trust project team members who are co-located in the same facility. This is natural given the constant interaction of co-located employees. The strength of trust between project teams and team members tends to be inversely proportional to the distance involved. It could be said that trust itself need not be extended in co-located teams since a follow-up on commitments may be carried out immediately. A “trust but verify” approach works well when verification of deliverables is a trivial matter. However, trust takes considerable effort to develop when verification and oversight is not so trivial. The further the physical distance, the less likely it is that the project team will be willing to assign important work without extensive controls in place. Further, physical distance is but one element of the trust equation. Differences in language, culture, and management of processes effectively increase the distance between project teams, thereby decreasing the level of trust. Project teams can learn lessons in developing trust by examining applications that are designed to create trust between users who are separated by physical distance. One familiar application in common use among globally distributed stakeholders is eBay. Consumers bid for products, they pay money to sellers when they win the bid, and they trust sellers to deliver the product as described. How is trust developed? By use of the feedback mechanism. Bidders trust sellers who have higher positive ratings. Project managers may consider ways to put feedback in place to develop a stronger performance track record. Projects are not likely to have a built-in review system such as eBay, but they can implement simple electronic survey and polling systems to collect frequent feedback and thereby build trust.

Trust and Distance Revisited

Since distance reduces trust between geographically distributed team members, one approach to building trust is to remove the distance—at least initially and perhaps periodically. As a practical example, consider bringing together representatives of the global teams involved in the project for a kick-off scheduling and team-building workshop. Time spent together in a workshop environment may aid in building initial trust relationships that aid in facilitating the day-to-day work at a distance (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 The relationship between trust and distance

Further, bringing together distributed team members periodically for project review and planning meetings helps to solidify trust relationships. Although working at a distance and working within virtual teams is the norm within the information age in which we live, this does not infer that face-to-face meetings are to be ruled out completely. Face-to-face encounters may never be a frequent possibility, but offering the opportunity for face-to-face interaction from time to time has the potential to minimize or eliminate miscommunication, a mismatch of expectations, and conflict.

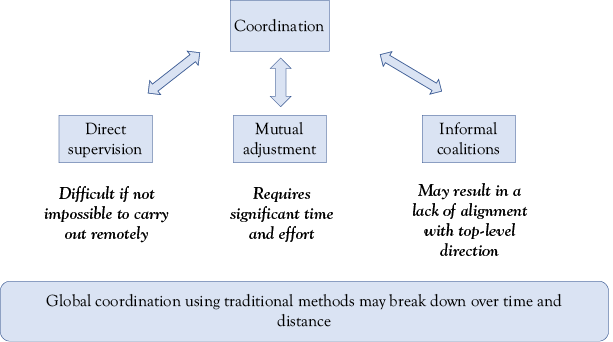

Distance and Management

It is observed that lack of trust between teams separated by physical distances makes it much more difficult for project managers to lead remote teams and guarantee affective outputs. How then should project managers approach managing geographically distributed teams? Mintzberg provides clarity in this matter by providing a framework for managing and coordinating teams. Four general methods are outlined by Mintzberg: (i) mutual adjustment, (ii) standardization, (iii) direct supervision, and (iv) informal coalitions. Of the four, direct supervision is not possible when managing teams over remote distances. In the absence of clear policy directives, the project manager and the distributed teams may gradually adjust to each other and ultimately find a reasonable means for working together. Also, in the absence of clear policies, globally distributed teams may begin to work together and gradually begin jointly asserting their own preferences for managing work and producing project deliverables (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 The difficulty of traditional coordination methods

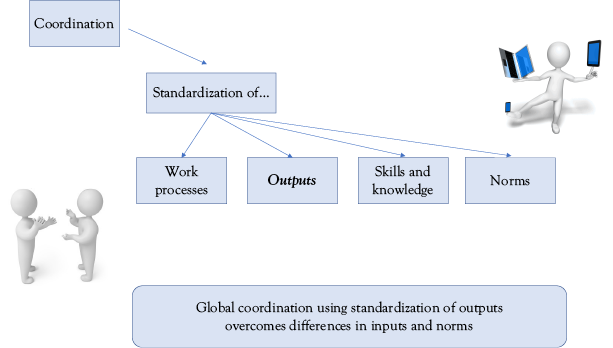

Given the difficulty of managing in an environment of mutual adjustment and coalitions as well as the physical impossibility of direct supervision, the project manager is left with standardization as the primary means for governing globally distributed teams. The question becomes, “standardize what?” Mintzberg proposes methods for coordinating work that could potentially be applied to global teams.

Standardization of Work Processes

The first of the suggested means for standardization is the standardization of “work processes.” Given that teams in different global regions may have their own standards and processes, and the direct supervision is not possible in the global project team environment, standardization using common work processes may not be the most viable approach for the global project manager. Mintzberg further proposes standardization of skills and knowledge. Skills and knowledge are important for producing quality project deliverables; however, skills and knowledge could be considered inputs to the process rather than outputs. Therefore, skills and knowledge do not necessarily equate to excellent performance outcomes.

Standardization of Norms

Norms may also be used to standardize how work is done across the globe. Norms work well only if all distributed team members are well-versed in such norms. This is usually the case when all team members are part of the same culture. But, it does not work in the global environment. Project team members at the head office may share a common culture and associated norms; so, the team should not assume that team members distributed around the globe are familiar with the same set of norms. When this happens, it often leads to false assumptions and miscommunication. A classic example of the result of the mismatch in norms is when Japanese companies carry out projects and operations outside of the home country. Japanese nationals are steeped in the norms of their culture and their country. Team members who are geographically distant typically will not exhibit such norms and further they may not even be aware of them. The resulting mismatch of expectations and frustration has long been observed to create havoc in Japanese global operations. Standardization using norms is therefore difficult to implement in practice.

Standardization of Outputs

What then are global project managers left with to manage and coordinate project work on a global scale? The fourth and final standardization technique is given by Mintzberg as “standardization of outputs.” This is a standardization method that lends itself to the management of global teams. Regardless of cultures, norms, and process differences, each team regardless of the location around the globe must produce deliverables that meet a clear, predefined standard. Such a standard could also be accompanied with checklists and detailed acceptance criteria. In terms of governance using such an approach, global teams could be charged with the execution of work packages to be delivered according to a clear scope standard and accompanied by a schedule and an associated budget. As long as the team meets the specified criteria within a specified tolerance, then the local team has a free rein to freely execute with minimal oversight. If the team determines that one or more elements of the agreed-on assignment cannot be met, then the local team calls for an oversight meeting to either cancel the work, revise it, or reassign it. The approach of managing local geographically distributed project teams using this form of Mintzberg’s standardization is less taxing on the team charged with the overall project responsibility and takes into account the common variability of inputs to project work products (Figure 2.5) (Mintzberg 1979).

Figure 2.5 Global coordination by standardization

Distant, but National

It is often the case that project managers lead large projects that involve multiple teams that are separated by physical distance—yet remain within the same country. Many of the principles of managing global projects apply. The “trust versus distance” concern applies whether the geographical distance does or does not cross international borders. Further, it is not uncommon for a single country to contain many different subcultures and different overall approaches to getting work done. Because of this, global project management principles offer many tools and techniques for building trust and coordinating work that could be just as easily applied in geographically dispersed national projects.