Culture is but one facet of global project management. Culture is intangible and perhaps more theoretical than the practical day-to-day issue that the project manager will face. Everything that a project team does in the course of executing the project will involve practical differences that may well lead teams to struggle. It is useful for project managers to remember that when it comes to daily life, there is no single way of doing things that should be considered “the right way.” Flexibility is always recommended when encountering and working with local norms. The saying “when in Rome, do as the Romans do” was quoted for a reason, and the reason is that fitting in to the extent possible in following local norms and customs is appreciated and can make the business of the project run much more smoothly.

Food and Culture

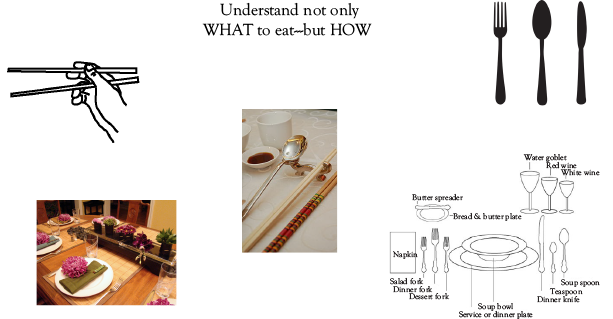

One of those important items that project managers and team members will encounter is food. Project stakeholders must eat to live, but what is eaten as a part of the daily diet routine differs considerably from region to region. Project team members working in different parts of the world will have to expect that the favorite local food from their home country may not always be available. Instead of hamburgers, project managers and team members are likely to encounter raw fish, unfamiliar meats and vegetables, spices, and unusual flavors (Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Culture differences and food

It goes a long way with global stakeholders if time is taken to appreciate the food that is presented and at least try the food and show appreciation. Regardless of the food presented, remember that all life comes from DNA, and seek to live with unfamiliar foods if possible. Another consideration involving food is not the “what” but the “how.” It is common in Western countries to use the knife and fork to eat. The use of the knife and fork, however, may differ between Western countries, particularly between the United States and Europe. Further, the number of forks, knives, and spoons used in serving a meal is likely to differ based on the level of formality of the meal. When, for example, a project manager is requested to go to dinner with a senior executive in Europe, learning which knife, fork, and spoon to use (along with “how to use them”) is important (Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2 Pay attention to “how” to eat in different cultural settings

Asian countries are well known for the use of chopsticks for eating. Practice is recommended for new chopstick users. When attempting to use chopsticks for the first time, avoid holding them close to the tip. Also, watch for “chopstick creep”—the tendency for sauces to crawl up the chopsticks and get on the hands. It is important as well to keep in mind that even though chopsticks are presented at most meals, not all foods will be eaten that way. Soup—except for the noodles and other solid components—is usually eaten with a large ladle-like spoon. Using such a spoon may make a loud “sipping noise” when using it, but it is accepted in most Asian settings and not considered impolite as it is in the West. Finally, keep in mind that not all meals in Asia will be eaten at a table. Some meals are served on the floor such as on Tatami mats in Japan.

Food and Religious Observances

Not everyone is able to share different food practices due to religious as well as health reasons. Some cultures eat beef but not pork and vice versa. Some cultures will consume only certain types of seafood. In addition to religious cultures, some team members may be vegetarian, vegan, or have specific food allergies. If project team members can enjoy local foods, so much the better. On the other hand, if some stakeholders are not able to partake in certain foods because of certain cultural, religious, or health restrictions, this is something that should be clearly noted and respected. Nothing conveys respect more than arranging for meals that is consistent with stakeholder observances or restrictions. Such meals that are arranged by project managers may need to consider requirements for halal or kosher, stipulation against alcohol and different types of meat such as pork, beef, and various types of shellfish (Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 Cultural and religious food observances

Also recall that the specific type of food may be only one part of the equation. Another issue is considering the focus on how the food is prepared. This requires some research up front, but in the context of a global project, it is a factor that must be considered especially among high-power/high-interest project stakeholders.

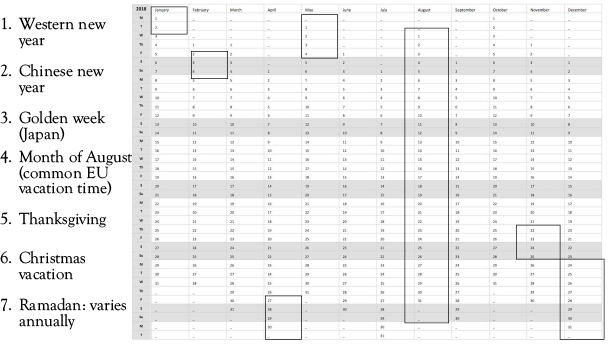

Holidays

Global project managers making plans and schedules must be aware that holidays around the world will vary considerably. Consider the difference between holidays in the United States and Europe. It is often said that there are two seasons in northern Europe: fall and winter. When August arrives, it is considered in Europe to be an ideal time to take a vacation. Project managers would do well to avoid scheduling important business with European clients around the August timeframe. Europe is not the only region that has holidays and holiday traditions different for many parts of the West. For example, Japanese companies typically observe something known as the “Golden Week.” Golden Week occurs twice a year—once in the spring and once in the fall. Recall that Japanese culture is highly collectivist in outlook, so it is therefore unsurprising that most of the nation tends to go on vacation at the same time during these weeks. Golden week is useful for companies because factories can be shut down for maintenance as well as to obtain significant cost savings by scheduling all vacations at the same time. Also, the strong work ethic of Japanese employees suggests that unless the workplace is completely closed, there is no feasible way to take a complete vacation. Therefore, the Golden Week holidays allow for this. In Western countries, the idea of synchronizing vacations during the Golden Week could seem intolerable. This is because Western countries are more individualistic in outlook and therefore everyone naturally expects to take a vacation on their own schedules. However, synchronized vacations work well in Japanese culture and project managers should be aware of what the annual Golden Week dates are. The annual New Year holiday is also a date that differs in different regions of the world. Western countries celebrate New Year on January 1 of each year. However, in China and other Asian countries, the Chinese New Year is an important celebration. This celebration takes place in February (Figure 8.4).

Figure 8.4 Global holiday calendar

While the Western project team may be shutting operations around December or January timeframe and become ready to start up and get back to business in late January early or February, this may be precisely the time the New Year’s Day celebration is occurring in Asia. The final holiday schedule that may be unfamiliar to many Western project managers is that of Ramadan. Ramadan is observed in Islamic countries or in countries where Islam is the dominant culture and Ramadan is a holiday that shifts from year to year since it is based on the lunar calendar. There is no one specific date when Ramadan is being observed at the same time every year, so it is something to consider when preparing for important project milestones in an Islamic country.

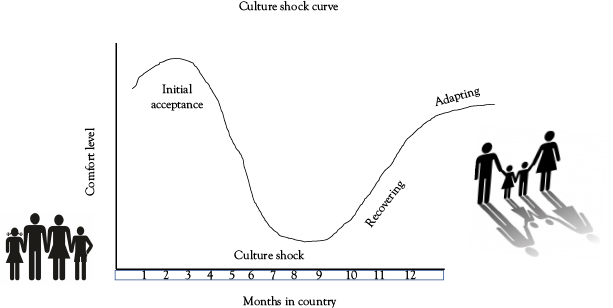

Culture Shock

Project managers and team members can find it very unsettling to have to live and work in a foreign country for an extended period of time. This phenomenon is known as culture shock. Culture shock can hit immediately after arriving in a foreign country. The intense feelings of culture shock may improve after time passes, but may become stronger, especially during the wintertime perhaps when depression can set in. Project managers and team members must be aware of the phenomenon of culture shock when making long-term assignments for a global project. It does not help in the culture change situation when an expatriate assignment is open-ended. Further, culture shock becomes a more significant concern when it is unclear what the project team member or project manager will be doing after the international project assignment has ended. In such a case, it is easy for the project manager to lose hope to be in the alien culture for an extended period and perhaps leave the project. The situation happens often. Perhaps not only because of the shock felt by the project manager in the alien culture but also due to the stress experienced by the family accompanying the project manager (Figure 8.5).

Figure 8.5 The culture shock curve

A global project manager should keep this in mind and ensure that in any extended assignment involving a foreign country, the assignment should be made only with a team member who has already been to that country and perhaps has already experienced an extended stay. Moving to a foreign country for an extended stay prior to having experienced any of that country’s culture is a very difficult move. Also, if the only available team member is the one who has not visited or lived in the foreign country prior to an extended assignment, it is highly recommended to send the team member there a few times for perhaps a couple of weeks at a time in order to become more familiarized with the local culture. Finally, it is good practice in an overseas assignment to allow return visits to the home country. When this policy is employed, the travelling team member will be advised regarding the number of visits home, how many are allowed by policy, how often, and then finally, the timeframe to return home as well as the role of the team member upon returning to the home country.

Culture Shock and Family

A project manager or team member may become familiar with a geographically distant country and culture, but it may be quite a different matter for the family. When sending a team member to another country with a different culture, it is important to consider whether the family will fare well in a different culture. It is also preferred to send only families who have some familiarity with the culture of the assigned country. The project sponsor should consider if the family of the team member being sent to another country has traveled abroad before and had experiences with other cultures. Another consideration might be the age of the children. Also, the project manager should determine if the spouse is employed and to what extent will moving to a different country affect her employment and overall financial situation. The question of whether a project team member can thrive in a distant country and another culture therefore goes far beyond an assessment of the individual but also includes family members. Finally, if the family is apparently ready and willing to move to a different country, there is also the consideration of additional expense. Can the project team afford to send an entire family overseas for an extended period and absorb this expense? Or is it better to ask a team member to visit the foreign country for several short stays over a period of several months perhaps 1–2 weeks at a time? (Figure 8.6).

Figure 8.6 Family relocation considerations

The important thing to remember is that it is never as simple as it may seem to send the team member to another country. There are elements of culture, culture shock, logistics including family member employment, the schools that the children attend, and language and cultural transition difficulties. The list of difficulties and risk is nearly endless. As in all complex activity undertaken by the project team, global team member assignments must be planned as a subproject using the five process groups.