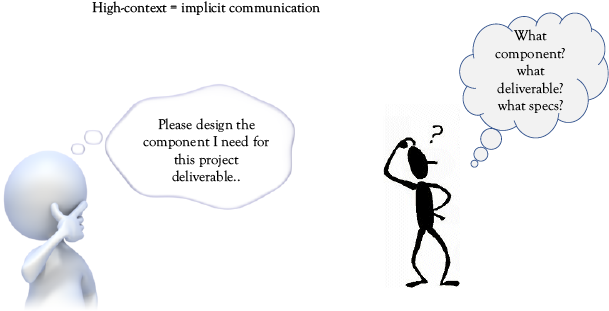

Behaviors, norms, and customs form different patterns in different geographical regions around the world. Cultural differences therefore are an obvious concern for global project managers. Many frameworks exist to provide guidance on understanding global cultures and managing across cultures. One aspect of culture that is often overlooked by project managers is the role of context. Context refers to the degree to which situational assumptions govern communications and relationship versus explicitly communicating each detail. One lens for evaluating cultural difference is provided by the observation that some cultures tend to rely significantly on context when it comes to communications and relationships. When context is a significant component of cultural behaviors, much is left unsaid and instead communicated only indirectly. This is because a culture that relies heavily on context is embedded with a common set of assumptions. In this case, much less needs to be directly “spelled out.” The context therefore plays a significant role in the communication channels when carrying out a global project. Some cultures may rely less on context and instead are explicit in communicating their views and requirements. What does this mean in practice for global project managers? When project managers interact with stakeholders from high-context cultures, communication is often less clear and more implicit. High-context communication tends to be less explicit because the context is used to carry a significant portion of the meaning (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 High-context and implicit communications

High-context cultures therefore tend to insist on building strong relationships prior to conducting business and communicating meaningfully. The relationships provide the context of business and communication. As an example, a project manager should never expect to meet an overseas client from a high-context culture and expect to do business shortly after meeting for the first time. Important project decisions and negotiations are not something that is likely to be done quickly in a high-context culture. Expect to spend time getting to know one another—perhaps on an informal basis—and then gradually “warm-up” to the prospect of doing business. To make an analogy, since the context is an essential to the communication, the “circuit” must be set up prior to communicating. In a telephone call, one must have a phone, and a connection, and then the communication takes place. In a high-context culture, the stage must be set with a personal relationship and a mutual understanding of the context. Then communications can flow. Asian cultures, including Japan, are said to be high-context cultures. Relationships and cultural norms play a key role in communicating important information that goes unsaid. Relationship-oriented business dealings are apparent in the web of keiretsu companies that work together in supplier, vendor, and financial relationships and they operate much like a family business. The emphasis on relationships rather than explicit documentation is evident in the number of lawyers per capita in Japan as compared to Western countries. Business that is done among friends and built from strong relationships can frequently be carried out on a handshake basis. Because of this, there is less reliance on letter of the law litigation among business parties.

Low-Context Culture

A low-context culture, by way of contrast, relies little on the context of the situation in order to conduct business. Neither relationship nor shared norms are assumed. Rather, the details of the engagement are spelled out in “black and white” using contractual arrangements. Whereas a high-context stakeholder may require a period of relationship building, a stakeholder from a low-context culture may be satisfied with an e-mail or a phone call. The low-context stakeholder drafts a written agreement that exhaustively documents all aspects of the engagement. Neither relationship nor norms are assumed or implied. Where would low-context cultures be found? Although Western countries in general tend to be lower in context than Asian countries, it is said that countries in northern Europe and Scandinavia are known to be representative of cultures significantly low in context than many others. It may be easier to strike a deal with the Scandinavian country by e-mail than with another country in Western Europe. This level of directness, brevity, and focus on the black-and-white again is not an option in high-context countries. High-context countries include many in Asia and Latin America that must be prepared with relationship building and face-to-face discussion prior to bringing up the subject of a possible business relationship.

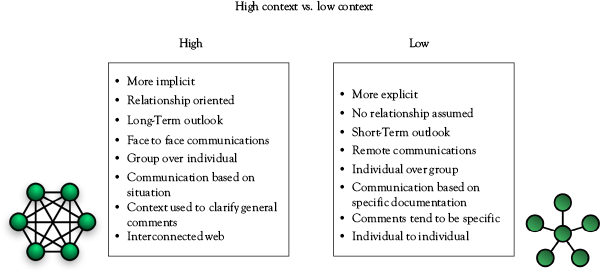

High- and Low-Context Compared

The differences observed between high- and low-context cultures may be summed up with a series of simple observations. High-context cultures tend to communicate more implicitly versus explicitly. High-context cultures are often more relationship-oriented rather than task-oriented in their outlook. High-context cultures assume shared norms and assumptions and tend to prefer long-term business relationships. Finally, high-context cultures emphasize tacit versus explicit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is the knowledge embedded inside the mind of a co-worker or colleague. Since business relationships are often long-term rather than short-term in high-context cultures, knowledge tends to remain within organizations since employees tend to remain with an organization as part of lifetime employment. The concept of “knowledge management,” which refers to the conversion of tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge as well as retaining knowledge when specific individuals leave the company, tends to be less of a concern within a high-context culture.

Low-context cultures favor documentation of rules, policies, procedures, and often communicate explicitly. Relationships are not assumed to be long term and this includes business relationships. Shared assumptions are not assumed, which infers that detailed and direct communication will be expected. Since knowledge in low-context cultures is explicit rather than tacit, it can be transferred more easily using documents, processes, and templates. Finally, low-context cultures will tend to prefer a task-oriented world-view (Figure 4.2) (Hall 1976).

Figure 4.2 High- versus low-context

Practical Implications of Context

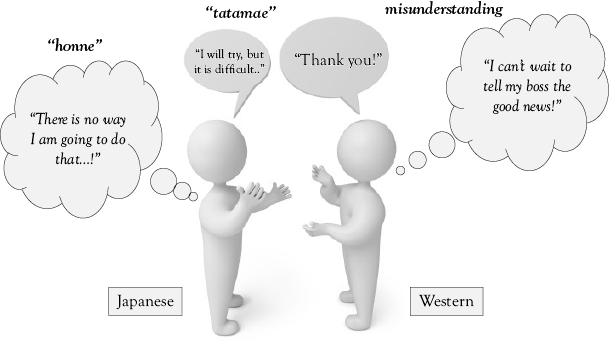

Rushing too quickly into a high-context project relationship is a common mistake made by first-time global project managers. There is also the possibility of misunderstanding when communication is attempted between a low-context project manager and a high-context stakeholder (or vice versa). An example from Japan helps to illustrate this. In the absence of clearly established norms within a new relationship, the low-context norms will naturally be assumed by the Japanese stakeholder. The assumption of low-context Japanese management cultural norms is that the harmony of an interaction must be safeguarded at all costs. This may mean that if the Japanese stakeholder does not agree with a proposed policy, direction, or offering, the stakeholder may not openly say so. Instead, the Japanese stakeholder may appear to agree when agreement was never intended. This relates to the principles of honne and tatamae. Honne is the underlying truth of the matter, whereas tatamae is the “face” put on a specific situation. Fellow Japanese nationals understand and interpret honne by observing facial expressions, tone of voice, and body language. However, Western nationals are not likely to understand this contextual channel of communication. Therefore, both parties are likely to separate with different understandings about what was agreed and what was not agreed to in the conversation (Figure 4.3).

Figure 4.3 Japanese–Western misunderstanding

This situation has additional implications when it comes to perspectives on project management and leadership. The Western, low-context tradition emphasizes the context of “integrity,” which is “to mean what is said and to say what is meant.” The Eastern, high-context view is “to mean what is communicated implicitly via the context, and to say what is most fitting in light of harmony preservation.” The high-context view works well within its own cultural context. However, when high-context individuals communicate in this manner to low-context cultures, the low-context stakeholder will likely view the result in terms of “being told a lie.” Likewise, when a low-context stakeholder communicates to a member of a high-context culture with presumption of “integrity,” the resulting direct and often blunt communication will usually be viewed as immature and a sign of weak leadership. When preparing to discuss policy, procedure, documentation, work orders, or processes, consider carefully which parties in the discussion are high versus low context in outlook. Understanding this will aid the global project manager in communicating the direction more effectively.

Process and Context

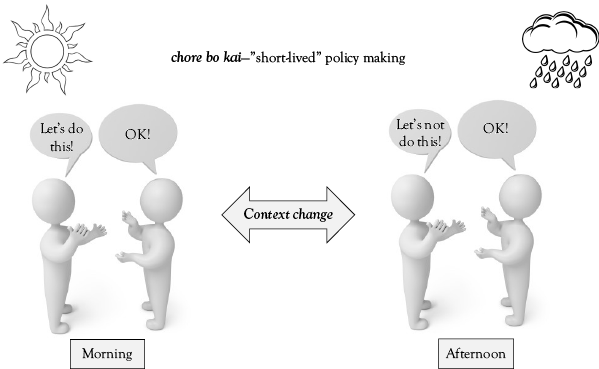

It is observed that formal, explicitly documented process as well as the concept of process maturity is a characteristic of low-context culture. A high-context work environment where relationships and cultural norms prevail is likely to rely primarily on implicitly communicated processes. Further, a more informal approach to getting things done that draws upon mutual relationship is commonly observed in high-context cultures. In addition to this, the constraints associated with the process may be observed to be constrictive and problematic given that the context in which business exists is always changing. After all, why be locked into “hard and fast rules” when the context doesn’t call for it? Japanese culture exhibits this in the concept of chore bo kai—the “short-lived” nature of making policy in the morning and proceeding to change it in the afternoon (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.4 Context-dependent decision making

This relationship between process management and high versus low context provides an additional rationale for management and coordination by the standardization of outputs. A high-context culture that uses implicit norms and strong relationships to get things done rather than black-and-white process documentation is difficult to assess from a distance. It is by far more straightforward to evaluate outputs of the processes using predetermined and pre-communicated acceptance criteria. Finally, it pays for global project managers to understand which teams will assume implicit norms and shared values (high context) versus those who do not and will likewise be more accepting of policy and process direction (low context).