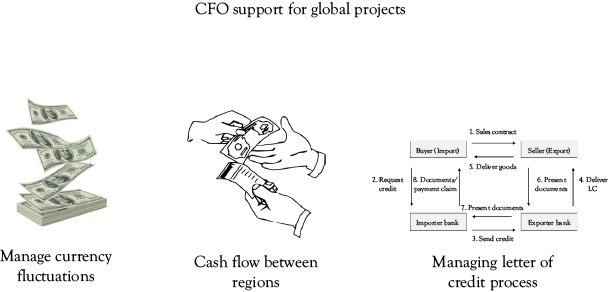

An experienced CFO (Chief Financial Officer) can be a big help in deciding how the project is to be funded when the work is carried out in many distributed geographical locations. Some basic questions to be asked include, “What is the source of funding in what currency will we pay for materials and labor and components?” Also, “What are the regulations associated with bringing in money and moving money out of (and between) different geographical locations?” Finally, the CFO will need to advise the project team about concerns such as currency fluctuations in countries in which the project team is working. For example, assume the global project manager managing a team that won a bid in a foreign country and the bid is for an information system that requires installation. The bid was one based upon an initial budget that included analysis of costs, but such a budget may not have included all eventualities of currency fluctuation. In the early stage of the project, therefore, it may be recommended to put a currency hedge in place to protect against fluctuations. Another important concern is obtaining payment from the client and ensuring that the client will pay for the products and services that the project provides. One way to do this is through the mechanism of “letter of credit” (LC) (Figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1 The letter of credit

The letter of credit is a financial instrument created between a customer in the geographically distant country along with the local bank of the client. The bank confirms that the client has the funds to pay for the deliverables. Further, the contractual terms are put in place such that when the project team meets its obligations for deliverables, the funding associated with the contractual terms are then released. The letter of credit therefore is a way of securing payment when it otherwise might be unclear whether the client has the means or if the client is likely to follow through with contractual fiduciary obligations.

Taxation

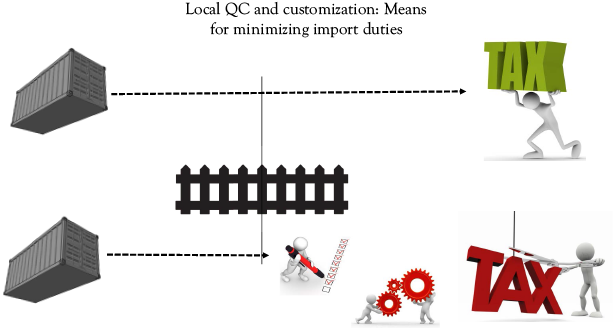

Another way the CFO can aid the project team is in providing advice on taxation. For example, a project that involves an installation in a foreign country and involves importing many pieces of equipment may be subject to significant import duties. This may require some creativity in order to be managed. Some Latin American countries, for example, have very high import duties on electronics products. However, such duties drop considerably when at least some work is done by local labor between the importing of the product and its destination to the local customer. It may be less expensive to import products and subsystems and have a local team test them, label them, and package them for the local market rather than import 100 percent finished goods (Figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2 Minimizing import duties

The cost of labor may be less than the cost of import duties. Another approach to addressing this challenge of import duties is to import within a more favorable country first. Consider as an example a project team based in China importing to the European Union (EU). Such a project team would experience high import duties importing finished goods into the EU. However, if subsystems are imported to a country with low local labor cost (e.g., the Czech Republic) and completed systems are manufactured at this interim operation, these in turn can be exported to the rest of the EU at much lower import duties than if the product came from China directly. As is the case of the Latin American example, this is a matter of comparing the costs of local labor versus the cost incurred by the import duties. In many cases the cost of local labor expended at some level of customization to produce finish systems of subsystems may be much less than import duties.

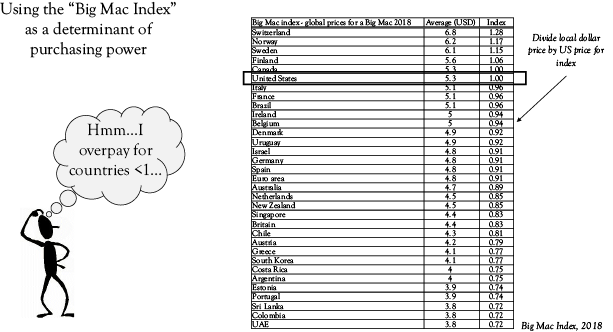

The Big Mac Index

How much does it really cost to live or to do business in a foreign country? One of the ways to answer this is to compare the value of currency of the home country to the country in which the project team seeks to do project business. The principle that applies in evaluating currency values in global projects is the concept of purchase price parity (PPP). Using PPP, it is possible to deduce to what extent currency is overvalued or undervalued by comparing the price of common goods in both countries and then comparing this against the exchange rate. Often this is done formally by comparing the price of the basket of commodities between two countries. However, the The Economist magazine has created a simple method to do this, which is both humorous as well as effective. To explain the approach of the The Economist, consider for example what might be found in a theoretical “basket of commodities” compared between countries. The comparison may include the cost of local labor, the cost to rent or buy property in which to do business, and local agricultural products such as grains, vegetables, dairy, and poultry, to name just a few. A simple way to compare such a bundle of commodities is to compare the price of the big Mac Hamburger from one country to another (Figure 10.3) (The Economist 2019).

Figure 10.3 The Big Mac Index

The Economist magazine does this and publishes a scale known as the big Mac index. The big Mac index compares price of Big Macs across many different countries and compares that to the currency exchange rate with the base currency, in this case the US dollar. When examining the prices of Big Macs around the world, it is easy to see which countries likely have overvalued versus undervalued currency.

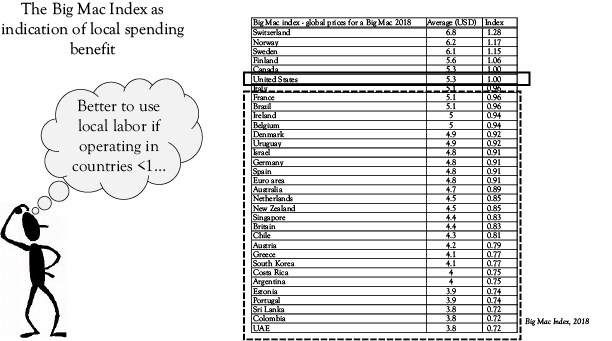

Responding to the Big Mac Index

As interesting is and as humorous as the big Mac index is, it begs the question, “What should global project managers do with this kind of information?” The degree to which a local currency is overvalued or undervalued goes a long way toward informing the project team where work should be done, labor should be hired, and facilities be established. As an example, if the home country currency is overvalued, the local country may be a preferred location for the team to develop deliverables for the project. The local country may also be the preferred location for hiring labor to carry out a major installation. Overvaluation in the home country shows that the home country currency could go much further in the geographically remote country than in the home country. If this is the case, it makes much more sense to hire local labor, lease local facilities, and do as much business as possible in the local currency (Figure 10.4).

Figure 10.4 Applying the Big Mac Index

If the reverse is true, for example, the geographically distant location has an overvalued currency compared to the home country, it may make more sense to minimize local hiring and send the project team members from the home country to live in the local country to compensate for the differences in currency valuation. A final consideration is to think about how the big Mac index has changed over time. If the project is expected to last for more than 12–18 months, it may be wise to understand the pattern of currency fluctuation over the past several years within that local country. Once the project team has established a strategy to manage valuation differences of currency between home country in the local country, it is best to avoid a major shift in strategy because of the sudden change in currency valuation. This has been known to happen in some countries. One example of this occurred several years ago in Venezuela. In 2010, there was a sudden 100 percent devaluation of the currency in Venezuela. Any project producing deliverables during this time would experience significant shock to the business plan if the project team is not prepared. This is an example of the financial risk that a project manager will need to keep in mind and think about carefully when assigning teams around the globe and making the decision between the degree to which the team uses labor, materials, and capital from the home country versus the geographically distant country.

Commercial Terms

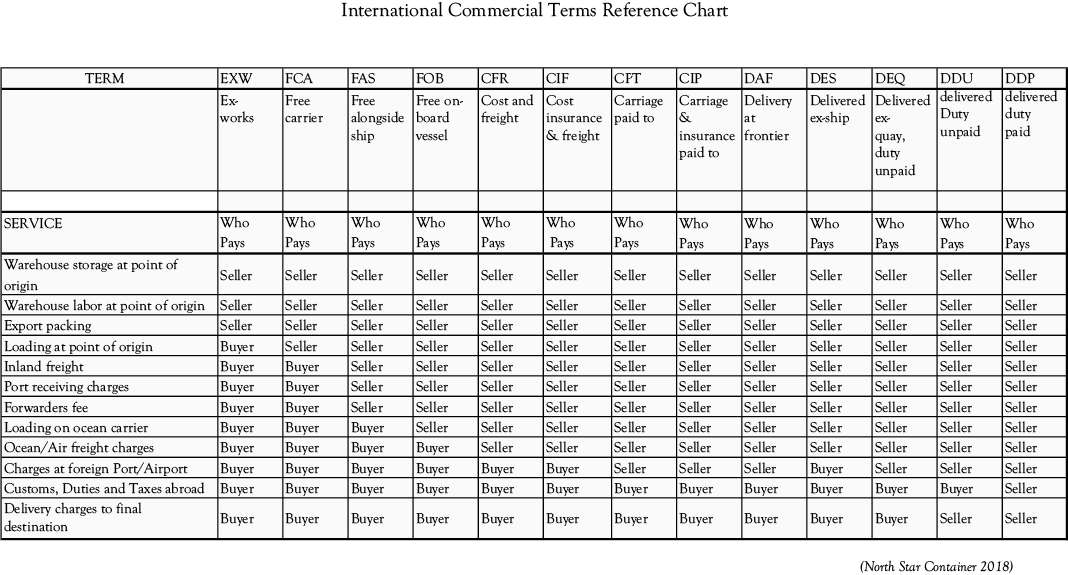

International commercial terms are provided in contracts in order to indicate specifically where transfer of title or ownership of a piece of property occurs. Assume, for example, a project team is managing a project in Europe and is shipping a major hardware component from a port in the United States such as New Jersey. Both parties in this transaction must know where transfer of title of the deliverables occur. If the terms include “FOB New Jersey” in the contract, this is a reference to “free on board,” which indicates that the transfer of title occurs when the equipment is placed on board the transport at the port from which it is shipping, in this case New Jersey. Prior to the equipment loaded onto the ship, the project team that produced the deliverables holds the title to the deliverables. Once the equipment is loaded on the ship however, the title is transferred to the client (if FOB commercial terms are so indicated). This means that in the case of a disaster where the ship sinks and the equipment is lost, it is not a loss to the project team. Once the title has transferred upon shipping, then payment according to contractual terms are now due from the client to the project team. It is incumbent upon the client to have insurance on the deliverables so that they are secure throughout the transport from, in this case, the port of New Jersey to the final destination in Europe. Global project managers must pay close attention to terms such as free on board. Another common international commercial term is “Ex-Factory” or “Ex-Works.” This indicates that title transfer of the deliverable occurs once it leaves the factory. If a project team is ordering component or subsystems as part of the integration a larger system, if, for example, the contract stipulates “Ex-Factory” or “Ex-Works,” then the project team must be aware that it is responsible for transporting the goods and that title to the goods is transferred to the project team once it left the factory. As a final note, FOB terms are quite common as EX works in X factory as the location of transfer of title is often so indicated on the contract (Figure 10.5) (Nscontainer.com 2019).

Figure 10.5 International commercial terms

For example, FOB Tokyo, FOB Munich, or Ex-Factory with reference to specific factory or ex-works with reference to a specific operation indicates the location at which the title is transferred. From there, the receiving party (the client, or the project team ordering components, materials, or equipment) takes ownership of the deliverable and it must ensure the safety of the components’ transport. Further, the receiving party must bear the cost from that FOB location to the ultimate destination. In contract negotiations, attention paid to contractual terms may make the difference between profit and loss. For example, if a subsystem ordered by a project team is manufactured in Tokyo, but the project team does not want the additional expense of insurance or trouble of transporting it from Tokyo, then a local FOB location could be secured as part of the contract. These are just a few examples of international commercial terms for which a global project team must be aware. Neglect of international commercial terms could be quite costly so it much be considered in the plan and in the execution of the global project plan.

Logistics and Delivery

In addition to the commercial terms in the contract for deliverables, global project teams are well advised to think through the logistics of shipping deliverables from one location to another. In major capital projects for example, it is important to evaluate if there is enough shipping and receiving infrastructure at the location where the project will be installed. Also, circumstances may call for the use of heavy equipment. However, heavy equipment may only be employed if the site can support it. The team must be able to answer further logistics-related questions such as, “Can the product being delivered be taken from ship loaded onto a train or truck and then delivered?” and “Could some portions of the deliverables be flown?” Also, “How difficult or expensive is it to move parts and equipment to the ultimate destination?”

There are locations that are difficult to reach by any means so as a recommendation the project team could consider employing a checklist to ensure that the team has thought through logistical difficulties for moving parts, equipment, and even people from one location to another. Another concern with logistics concerns the role of customs. How easy or difficult is it to get the parts or components and labor for shipping from one country to another? Does it require special intervention by local agents or legal professionals? How accurate does the paperwork need to be and what happens if there are errors in the customs paperwork? (Figure 10.6).

Figure 10.6 Logistics and customs

Logistics is an area of risk analysis where it pays to consider scenarios of what could possibly go wrong. Finally, there may be regulations on the type of equipment that can and cannot enter a country. Further, even if the equipment being used by the project meets such requirements, if it is close to the borderline of being a problem, it may remain in customs for an extended period for enhanced inspection. Also, there will be times when an important component or piece of software or piece of equipment or tools may need to be rapidly shipped to the global project destination to address an urgent concern. In such a case is it even possible to expedite such goods through local customs? What actions could the project team take if there are no means for expediting the entry of parts, components, tools, and equipment through local customs? Unfortunately, some project teams who have encountered such an urgent situation with little other recourse may attempt to bring parts, components, or tools into the country by themselves perhaps on a commercial flight. This is a dangerous practice as it could lead to fines, arrest, or even imprisonment. Always remember that project teams are the guests in other countries. Failure to follow the rules could end up with severe penalties. Throughout all PMBOK processes, there is an emphasis on “plan first, then do.” This is most important when it comes to thinking through how to move goods and supplies from the home country to the end destination and to navigate through the rocky shoals of local customs officers.