Project managers frequently communicate informally and perhaps very rapidly with team members in their own language in the home country. The day-to-day informal conversation back and forth between team members can lead to extensive use of informal and idiomatic expressions. This poses no problem between members of the same culture; however, when crossing cultures and communicating to non-native English speakers, the rapid use of informal conversational and idiomatic expressions could be a subject of much confusion. As an example, consider typical English expressions such as “hurry up,” “calm down,” “down in the dumps,” “hands down,” “keep your chin up,” or “catch up.” A native English speaker will immediately understand the intended meaning behind these idiomatic expressions. However, someone from another country who did not grow up speaking English may find such phrases confusing. For example, when the phrase “hurry up!” is expressed, it is not surprising to observe a non-native English speaker looking up. Or, when saying “calm down!” the term “calm” could be understood, but the term “down” may be unclear in this instance. Native English speakers understand that “down” does not really mean “down” in this case but is instead an idiomatic expression. As is the case with most idiomatic expressions however, it is one that does not clearly express the intended meaning to a non-native English speaker (Figure 9.1).

Figure 9.1 Avoid idiomatic expressions

What this suggests is that project managers working with team members in other countries should simplify their communication and as much as possible avoid specialized and idiomatic expressions. Instead, use the simplest possible way of expressing a thought at all times. A fellow English speaker, upon hearing a project manager speaking to a non-native English speaker in a very simple way, may think of what is being expressed as “baby talk.” If talking in a plain, simple, and direct manner helps communicate information clearly and succinctly, then it is recommended to use it. Keeping in mind the mathematical expression of the “least common denominator,” project managers should seek to be understood by that one person least able to understand English. This will naturally require a simplicity of expression without idiomatic expressions.

Deciphering Non-Native English Usage

The problem of communicating in a foreign country goes both ways. Native English speakers can confuse others by using idiomatic expressions, but on the other hand non-native English speakers can use what native speakers would consider to be “broken English.” Do not be surprised when unusual usage patterns arise from non-native English speakers in conversations. These include phrases that do not necessarily make sense as well as occasional profanity. A non-native speaker of English may use profanity without being aware of its meaning or the shock it may cause when the word is spoken. Project managers are encouraged to be understanding when interacting with non-native English speakers and consider that their facility with English language may be limited. Because of this, sometimes some rather surprising expressions may appear in the conversation. The same is true of writing e-mails or documents. Upon receiving an e-mail that doesn’t make sense or comes across as offensive, project managers are encouraged to take a deep breath and think about the possible intent behind the e-mail or message. It is advisable to pick up the phone or initiate a video conference and discuss the issue or hold a meeting with the individual who sent the e-mail prior to letting the situation become inflamed or result in unnecessary conflict (Figure 9.2).

Figure 9.2 Anticipating language problems

Finally remember that when broken English is heard or perhaps a T-shirt with some unusual English expression is observed, avoid the temptation to laugh or mock. Remember also that it is not uncommon for native English speakers to wear shirts or pieces of jewelry with Chinese characters while being unaware of their meaning. Such a character may mean something that is offensive to those who can understand it but not offensive at all to an English speaker who has no idea what the symbol could mean. Also, when it comes to exchanging information, do not neglect the high-context versus low-context consideration. Some information may be more appropriate to be handled in a face-to-face meeting rather than an e-mail or conference call. Some communication should not take place at all unless the relationship is first developed. For example, sending an electronic survey to several team members residing within a high-context country will typically not yield very many responses. Responding to a survey devoid of the relationship context creates uncertainty and sometimes confusion. It is essential for the communication plan of a global project therefore to map the choices of media to the category of messages and direction that it is sent back and forth. The plan should also take into account elements of cultural dimensions as well as the differentiation between high- and low-context communication.

Connectivity

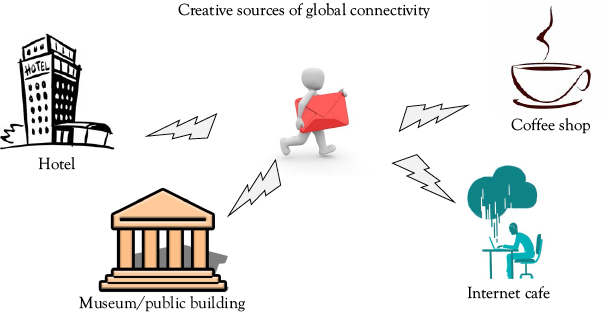

Communication in remote areas can only happen if there is appropriate media for sending and receiving information. The Internet is nearly ubiquitous, but it is important to keep in mind that some areas of the world lack Internet or lack the high-bandwidth Internet that is very common in developed countries. Project teams must consider this in advance and plan for how e-mail and transfer of files will take place in remote areas. For example, low-bandwidth Internet is enough for e-mails and there may be local telecommunications systems to satisfy the need for voice communication. However, there may be insufficient bandwidth to support teleconferencing or transferring of very large files (Figure 9.3).

Figure 9.3 Sources of global connectivity

It may be the case that the project team visits the client site to conduct an installation and discovers that the team needs a major software upgrade that can only be delivered through the Internet. What if this is a need that is foreseen but the connectivity at the local factory or job site is insufficient? It may be that in such a case the project team would need to return to the hotel if it is quite advanced in communication and has enough bandwidth capability, or perhaps go to a local restaurant, coffee shop, or Internet café. The key message for connectivity is to think ahead. Consider what action would need to be taken if the required bandwidth is not there and where are possible islands of bandwidth that the project team could take advantage of to get the job done when the need for bandwidth exists and the available options are few.

Nonverbal Communication

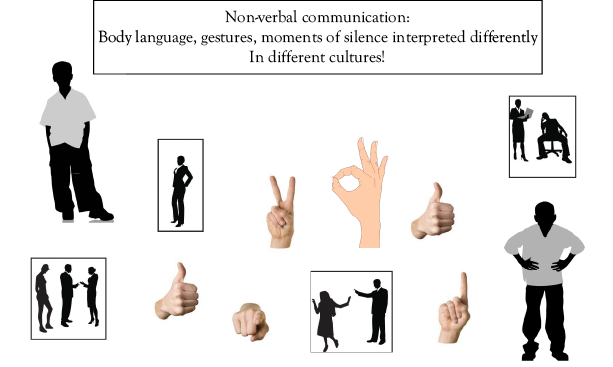

Differences in language and the complexity of expression that are often involved in the use of idiomatic expressions lead to a significant breakdown of communication. However, the spoken word is not the only communication channel used between project team members and stakeholders within other countries’ regions and cultures. Nonverbal communication is always involved in face-to-face and in video conference call settings. Nonverbal communication involves facial expressions, posture, gestures, and even the tone in which something is spoken. Global project team members must be attuned to nonverbal cues that they send intentionally or unintentionally as well as those received by parties from different cultures. For example, it is not uncommon to sit in a meeting with Japanese stakeholders and see one or two meeting members apparently dozing off in the meeting. However, if the name of that individual is addressed, that person will suddenly perk up and respond immediately. When this behavior is observed, it is not necessarily an example of sleep but rather an example of contemplation. Likewise, it is not uncommon to have long periods of silence in a conversation within a high-context culture (Figure 9.4).

Figure 9.4 Non verbal communication

Western project managers are often confronted with long periods of silence and may seek to fill it by talking. This is rarely a good idea as the project manager may say too much or send the wrong message to the other part. The silence should be appreciated and often it is useful to mirror the behavior of the stakeholder who is the party to the communication. Gestures are another potential minefield for face-to-face communication between different cultures. Hand gestures that may have an innocuous meaning in the Western world may be interpreted as demeaning, insulting, or even profane in some cultures. Such gestures are not limited to the hands but also perhaps the shrug of the shoulders or a display of the soles of the feet. Project managers embarking on projects in other countries and cultures should do research to understand which gestures are acceptable and which should be avoided. If possible, discuss the matter with a national or local from the country with which the project team is expected to do business and ask detailed questions. On the other side of this equation, it is important to avoid misinterpreting gestures, posture, or other nonverbal cues from the stakeholder from a different culture and take offense. For example, it is not uncommon in Asian countries to be in a conversation with another party and to observe the person holding his or her arms folded tightly across the chest. From a Western perspective, this might be interpreted as the person being resistant or adamant with respect to a point. Although this may be the inference taken, it may not mean that all in the other culture. It may simply be a relaxed position and therefore an indication of an expression of interest. In addition to being careful about posture, periods of silence, tone of voice, and gestures, don’t read too much into other nonverbal cues that may be misinterpreted as something negative when they are, in fact, not. A final aspect of nonverbal communication is eye contact. In many Western countries, eye contact is considered very important. It is a gesture of directness and often a symbol of integrity. This is not true in all cultures where having direct eye contact could be considered impolite. If an engaging in conversation with a stakeholder from another culture and limited eye contact is detected, this may be a cultural artifact rather than example of the individual attempting to mislead or to deceive as it may be interpreted in the West.

Mirroring

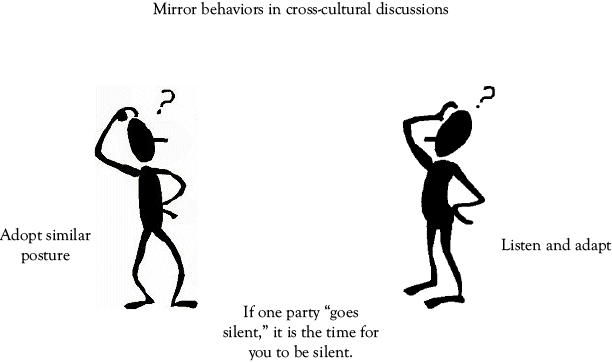

Project managers who have observed interviewing techniques, for example, in the context of a television crime drama, will often notice that the interrogator when asking questions of the witness may tend to mirror the behaviors of the witness. In this context, if the interviewee leans back in the chair so does the interviewer. If the interviewee puts his chin on his or her hand and leans forward so does the interviewer. Also, if the subject being interviewed pauses and does not speak for a while, the interviewer typically also does not talk and lets the silence pass. The approach of mirroring is a reasonable one for project managers in global teams communicating across cultures. This is especially true when interacting with stakeholders who are not native English speakers. It is best to be patient, remain quiet and reserved, and in the absence of being able to speak the language seek to behave in a manner that best represents the local culture. In fact, behaving similarly to others within that local culture may be preferred over attempting to speak the language (Figure 9.5).

Figure 9.5 Mirroring communication behaviors

For example, having a Westerner attempt to speak Chinese in the People’s Republic of China will likely catch a Chinese national off guard and may seem strange to the Chinese national at first. Further, it is highly likely that attempting such a maneuver will lead to mistakes, some of which may be embarrassing. This leaves project team members with the overall communication advice of mirroring local behaviors, remaining quiet calm and reserved, and avoid straying into unfamiliar areas. Take special care when attempting to speak an unfamiliar language. Language and culture is a very deep well. If the project team member has not grown up with the culture and is not fluent in the language from an early age, then the team member is only exposed to a drop in the bucket compared to an ocean of underlying know-how and meaning. It is unlikely that a project team member project manager will be able to fully tap into this cultural body of knowledge. It is therefore preferred to remain reserved, speak through an interpreter, or by using the native language of the project team including very simple basic terminology.

Negotiation

The natural give-and-take of negotiation is an important facet of any project. Negotiation is also part of life in global projects. The unique difficulties associated with negotiation in international projects is that different cultures have different approaches to the natural back-and-forth bargaining and discussion that occurs within a negotiation. High-context cultures require a period of getting to know one another prior to even beginning the commercial discussion that takes place in the negotiation context. Further, it is essential to expect that the other party to the negotiation may sit in silence for a few minutes after a proposal. As is the case in day-to-day conversations, Western team members inevitably attempt to fill periods of silence with talk and such unneeded talk may cause negotiations to become unraveled. Also, a period of silence may lead to multiple concessions that are unnecessary. What is necessary is to understand that different cultures may tend to respond to comments in a negotiation, an offer, or a counteroffer in ways that are unexpected (Figure 9.6).

Figure 9.6 Getting started in international negotiations

A significant difficulty faced by Western project managers in global projects is the fact that some cultures are not able to disagree or to say “no” in a direct fashion. Project managers from low-context countries who are more familiar with a more direct approach in communication may believe that the other party to the negotiation has agreed with something when, in fact, no agreement exists at all. Often the difficulty of obtaining a straight “yes or no” answer is related to the fact that no single individual may make the decision for the group within the context of a collectivist culture. In the case of a major decision, an individual within a collectivist culture may need to propose the idea, socialize it, hold several meetings about it, and continue to interact within the organization until a consensus position finally emerges. Upon the project manager hearing a quick “yes or no” within a project negotiation, it bears remembering that an individual response may in reality mean little until the entire group, which the individual represents, has had an opportunity to weigh in and achieve consensus. Above all, the additional variables encountered in negotiations in the global environment reinforce the dictum that “patience is a virtue.” An agreement that works for both sides is likely to take time to gel.

Common Goals in Global Negotiations

While significant differences exist on each side of the table between negotiating parties in global negotiations, it is important to understand what both sides are likely to have in common. Each party may be constrained by its cultural norms with respect to what is said as well how it is expressed. However, it is essential to remember that for both sides, negotiation is an exercise in trading. Trading between cultures is an activity that has existed from the dawn of time. With the perspective of trading in mind, global project teams can view project negotiations as a form of problem solving. Each side is at the negotiation table to fill a business need. Further, each side has access to resources that are valued less than the resources that each side seeks to fill. Negotiation is therefore an exercise in trading what is less needed for that which is most needed. When both sides of the table can achieve this, the negotiation is a success.

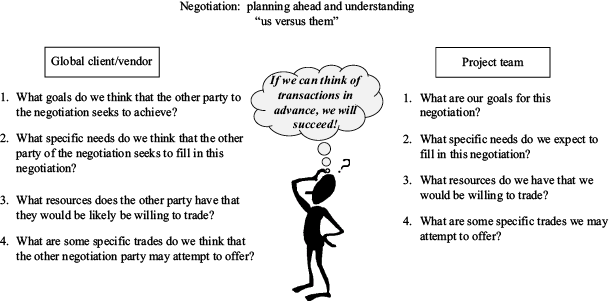

With the goals of the negotiation firmly in mind, the project team can prepare for the negotiation meeting by documenting answers to the following questions:

- What are the goals of the negotiation?

- What specific needs do we expect to fill in this negotiation?

- What resources do we have that we would be willing to trade?

- What are some specific trades we may attempt to offer?

Further, to prepare for the negotiation meeting, the project team should consider the same questions but from the perspective of the other negotiating party. For example:

- What goals does the other party of the negotiation seek to achieve?

- What specific needs does the other party of the negotiation seek to fill in this negotiation?

- What resources does the other party have that they would be likely be willing to trade?

- What are some specific trade-offs do we think that the other negotiation party may attempt to offer? (Figure 9.7).

Figure 9.7 Planning ahead in negotiation

The answers to each of the questions asked from both sides result in what could be viewed as a “negotiation plan.” Beginning a negotiation meeting with a negotiation plan in place can aid global project managers by helping them stay focused on the goals without getting distracted by significant differences in approach exhibited within cross-cultural negotiations.

Managing a Cross-Cultural Project Negotiation

The first step in managing a cross-cultural negotiation is to determine the location for the negotiation. Recall that in international travel it is often easier to travel west when attending an important international meeting scheduled the next morning following arrival at the distant geographical location. Therefore, when planning a negotiation with a global project stakeholder or supplier, if the team has the option to choose a location outside of the country, it is recommended that the team select a location that allows for the negotiating party to travel west. Traveling west helps the visiting team feel more refreshed and relaxed during the first morning. Conversely, the other negotiation partner who had to travel east faces the difficulty of waking up far earlier than her normal schedule would allow for.

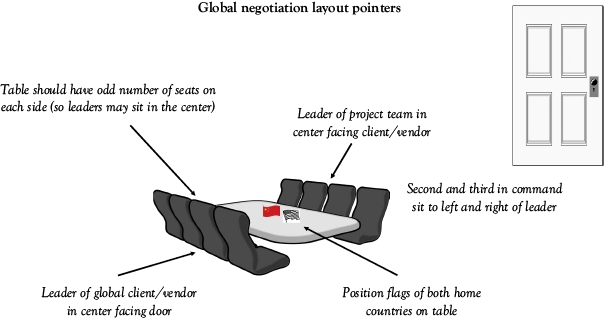

The next item involved in managing the negotiation is selecting the actual venue or room in which negotiations take place. Note that some cultures prefer table that is positioned in such a way that the person sitting faces the door as it opens. For example, it is common for dinner meetings in China to have a table so that host can sit and face the door. This may be something that those preparing for the meetings need to keep in mind. Consider also the seating arrangements at the table (Figure 9.8).

Figure 9.8 Global negotiation layout

While it is common in Western countries to have the head of the company sit at the end of a long board room table, it is more typical in Asian countries to have the leadership take the center of the table. Likewise, the next highest in rank sits at the left and right hand of the leader who is seated at the center of the table. This is an essential aspect of arranging the table and failure to arrange it appropriately will cause confusion and embarrassment, and it may be taken as an offence by the negotiating partner. As a courtesy, once table setting arrangements have been made, it may be beneficial to provide a seating arrangement layout map to negotiating counterparts for review and approval before finalizing seating arrangements.

Managing the Setting of the Negotiation

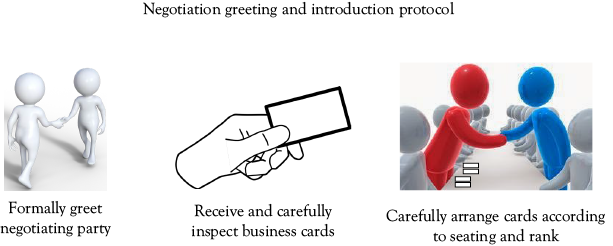

When the day arrives for the negotiation and both negotiating parties begin arriving, consider the fact that members of the other side of the table may be from a high-context culture or may be a mix of high- and low-context cultures. If this is the case, it is better to avoid negotiation prior to having some pre-meetings. An example of pre-meetings could include a dinner on the evening before the negotiations and possibly several meetings in advance in order to build that friendship. Given some context to the negotiating meeting has been established, when both parties arrive at the meeting room, it is common to present business cards to each other. Pay attention to the exchange of business cards, particularly in Asian countries. Changing business cards can be highly ceremonial and the card is often considered the extension of the individual who owns it. Therefore when a business card is received, accept the card with both hands and examine it carefully. Do not immediately place it in the pocket, but hold it and play close attention to it. It is considered polite to ask questions about the card, pronounce the name, and acknowledge the title. Likewise, when presenting a business card, present it with both hands as a gesture of respect to the other side. After initial greetings in the exchange of cards, when it is time for the project manager take the seat at the table, arrange the cards on the table, put them in order of rank, and make note of the cards and individuals. Acknowledge that it is recognized which card belongs to whom to as well as where is the corresponding person seated around the table. This is a gesture of respect (Figure 9.9).

Figure 9.9 Greeting and introductions in negotiation

Once both negotiating parties are seated, it is time for the negotiation discussions to begin. Since there may be a mix of people from high- and low-context cultures present, it is best not to start directly into a discussion of business. Instead talk about the weather, family members, sports, or other trivial matters to take a little time to warm up the meeting room. Perhaps introduce some light humor and get the conversation going. After adding this dash of informality to the process, gradually bring the topic around to the subject at hand. In the beginning stages of negotiation, it is best to talk in very general terms about what the goals are perhaps and understand what possible goals of the other side may be. Speak in general terms what it is that the team seeks to accomplish in this negotiation and what the project team may be willing to trade in return for it. Keep in mind though that the initial discussions are intended to be exploratory in nature. Eventually the conversation becomes more in-depth and serious. Details may begin to flow from the initial general exchange of information. Take care not to rush this process. It may be a good idea to bring in a white board, preferably one that prints out what has been captured on the board. Use this to capture key points for print out and review. These activities then eventually lead to proposals and then eventually to offers. The main principle is to be patient, to avoid talking during periods of silence, and to avoid revising proposals or offers during extended periods of silence.