CHAPTER 6

![]()

Programming with Objects

Chapters 2 through 5 dealt with the basic constructs of F# functional and imperative programming, and by now we trust you’re familiar with the foundational concepts and techniques of practical, small-scale F# programming. This chapter covers language constructs related to object programming.

Programming in F# tends to be less “object-oriented” than in other languages, since functional programming with values, functions, lists, tuples and other shaped data is enough to solve many programming problems. Objects are used as a means to an end rather than as the dominant paradigm.

The first part of this chapter focuses on object programming with concrete types. We assume some familiarity with the basic concepts of object-oriented programming, although you may notice that our discussion of objects deliberately deemphasizes techniques such as implementation inheritance. You’re then introduced to the notion of object interface types and some simple techniques to implement them. The chapter covers more advanced techniques to implement objects using function parameters, delegation, and implementation inheritance. Finally, it covers the related topics of modules (which are simple containers of functions and values) and extensions (in other words, how to add ad hoc dot-notation to existing modules and types). Chapter 7 covers the topic of encapsulation.

This chapter deemphasizes the use of .NET terminology for object types. However, all F# types are ultimately compiled as .NET types.

Getting Started with Objects and Members

One of the most important activities of object programming is defining concrete types equipped with dot-notation. A concrete type has fixed behavior: that is, it uses the same member implementations for each concrete value of the type.

You’ve already met many important concrete types, such as integers, lists, strings, and records (introduced in Chapter 3). It’s easy to add object members to concrete types. Listing 6-1 shows an example.

Listing 6-1. A Vector2D Record Type with Object Members

/// Two-dimensional vectors

type Vector2D =

{ DX : float; DY : float }

/// Get the length of the vector

member v.Length = sqrt(v.DX * v.DX + v.DY * v.DY)

/// Get a vector scaled by the given factor

member v.Scale(k) = { DX = k * v.DX; DY = k * v.DY }

/// Return a vector shifted by the given delta in the X coordinate

member v.ShiftX(x) = { v with DX = v.DX + x }

/// Return a vector shifted by the given delta in the Y coordinate

member v.ShiftY(y) = { v with DY = v.DY + y }

/// Return a vector shifted by the given distance in both coordinates

member v.ShiftXY(x,y) = { DX = v.DX + x; DY = v.DY + y }

/// Get the zero vector

static member Zero = { DX = 0.0; DY = 0.0 }

/// Return a constant vector along the X axis

static member ConstX(dx) = { DX = dx; DY = 0.0 }

/// Return a constant vector along the Y axis

static member ConstY(dy) = { DX = 0.0; DY = dy }

You can use the properties and methods of this type as follows:

> let v = { DX = 3.0; DY=4.0 };;

val v : Vector2D = {DX = 3.0; DY = 4.0;}

> v.Length;;

val it : float = 5.0

> v.Scale(2.0).Length;;

val it : float = 10.0

> Vector2D.ConstX(3.0);;

val it : Vector2D = {DX = 3.0; DY = 0.0}

As usual, it’s useful to look at inferred types to understand a type definition. Here are the inferred types for the Vector2D type definition of Listing 6-1.

type Vector2D =

{DX: float;

DY: float;}

with

member Scale : k:float -> Vector2D

member ShiftX : x:float -> Vector2D

member ShiftXY : x:float * y:float -> Vector2D

member ShiftY : y:float -> Vector2D

member Length : float

static member ConstX : dx:float -> Vector2D

static member ConstY : dy:float -> Vector2D

static member Zero : Vector2D

end

You can see that the Vector2D type contains the following:

Let’s look at the implementation of the Length property:

member v.Length = sqrt(v.DX * v.DX + v.DY * v.DY)

Here, the identifier v stands for the Vector2D value on which the property is being defined. In many other languages, this is called this or self, but in F# you can name this parameter as you see fit. The implementation of a property such as Length is executed each time the property is invoked; in other words, properties are syntactic sugar for method calls. For example, let’s repeat the earlier type definition with an additional property that adds a side effect:

member v.LengthWithSideEffect =

printfn "Computing!"

sqrt(v.DX * v.DX + v.DY * v.DY)

Each time you use this property, you see the side effect:

> let x = {DX = 3.0; DY = 4.0};;

val x : Vector2D = {DX = 3.0; DY = 4.0;}

> x.LengthWithSideEffect;;

Computing!

val it : float = 5.0

> x.LengthWithSideEffect;;

Computing!

val it : float = 5.0

The method members for a type look similar to the properties but also take arguments. For example, let’s look at the implementation of the ShiftX method member:

member v.ShiftX(x) = { v with DX = v.DX + x }

Here the object is v, and the argument is dx. The return result clones the input record value and adjusts the DX field to be v.DX+dx. Cloning records is described in Chapter 3. The ShiftXY method member takes two arguments:

member v.ShiftXY(x, y) = { DX = v.DX + x; DY = v.DY + y }

Like functions, method members can take arguments in either tupled or iterated form. For example, you could define ShiftXY as follows:

member v.ShiftXY x y = { DX = v.DX + x; DY = v.DY + y }

However, it’s conventional for methods to take their arguments in tupled form. This is partly because OO programming is strongly associated with the design patterns and guidelines of the .NET Framework, and arguments always appear as tupled when using .NET methods from F#.

Discriminated unions are also a form of concrete type. In this case, the shape of the data associated with a value is drawn from a finite, fixed set of choices. Discriminated unions can also be given members. For example:

/// A type of binary trees, generic in the type of values carried at nodes and tips

type Tree<'T> =

| Node of 'T * Tree<'T> * Tree<'T>

| Tip

/// Compute the number of values in the tree

member t.Size =

match t with

| Node(_, l, r) -> 1 + l.Size + r.Size

| Tip -> 0

SHOULD YOU USE MEMBERS OR FUNCTIONS?

Using Classes

Record and union types are symmetric: the values used to construct an object are the same as those stored in the object, which are a subset of those published by the object. This symmetry makes record and union types succinct and clear, and it helps give them other properties; for example, the F# compiler automatically derives generic equality, comparison, and hashing routines for these types.

However, more advanced object programming often needs to break these symmetries. For example, let’s say you want to precompute and store the length of a vector in each vector value. It’s clear you don’t want everyone who creates a vector to have to perform this computation for you. Instead, you precompute the length as part of the construction sequence for the type. You can’t do this using a record, except by using a helper function, so it’s convenient to switch to a more general notation for class types. Listing 6-2 shows the Vector2D example using a class type.

Listing 6-2. A Vector2D Type with Length Precomputation via a Class Type

type Vector2D(dx : float, dy : float) =

let len = sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy)

/// Get the X component of the vector

member v.DX = dx

/// Get the Y component of the vector

member v.DY = dy

/// Get the length of the vector

member v.Length = len

/// Return a vector scaled by the given factor

member v.Scale(k) = Vector2D(k * dx, k * dy)

/// Return a vector shifted by the given delta in the Y coordinate

member v.ShiftX(x) = Vector2D(dx = dx + x, dy = dy)

/// Return a vector shifted by the given delta in the Y coordinate

member v.ShiftY(y) = Vector2D(dx = dx, dy = dy + y)

/// Return a vector that is shifted by the given deltas in each coordinate

member v.ShiftXY(x, y) = Vector2D(dx = dx + x, dy = dy + y)

/// Get the zero vector

static member Zero = Vector2D(dx = 0.0, dy = 0.0)

/// Get a constant vector along the X axis of length one

static member OneX = Vector2D(dx = 1.0, dy = 0.0)

/// Get a constant vector along the Y axis of length one

static member OneY = Vector2D(dx = 0.0, dy = 1.0)

You can now use this type as follows:

> let v = Vector2D(3.0, 4.0);;

val v : Vector2D

> v.Length;;

val it : float = 5.0

> v.Scale(2.0).Length;;

val it : float = 10.0

Once again, it’s helpful to look at the inferred type signature for the Vector2D type definition of Listing 6-2:

type Vector2D =

class

new : dx:float * dy:float -> Vector2D

member Scale : k:float -> Vector2D

member ShiftX : x:float -> Vector2D

member ShiftXY : x:float * y:float -> Vector2D

member ShiftY : y:float -> Vector2D

member DX : float

member DY : float

member Length : float

static member OneX : Vector2D

static member OneY : Vector2D

static member Zero : Vector2D

end

The signature of the type is almost the same as that for Listing 6-1. The primary difference is in the construction syntax. Let’s look at what’s going on here. The first line says you’re defining a type Vector2D with a primary constructor. This is sometimes called an implicit constructor. The constructor takes two arguments, dx and dy. The variables dx and dy are in scope throughout the (nonstatic) members of the type definition.

The second line is part of the computation performed each time an object of this type is constructed:

let len = sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy)

Like the input values, the len value is in scope throughout the rest of the (nonstatic) members of the type. The next three lines publish both the input values and the computed length as properties:

member v.DX = dx

member v.DY = dy

member v.Length = len

The remaining lines implement the same methods and static properties as the original record type. The Scale method creates its result by calling the constructor for the type using the expression Vector2D(k * dx, k * dy). In this expression, arguments are specified by position.

Class types with primary constructors always have the following form:

type TypeName <type-arguments>optional arguments [ as ident ] optional =

[ inherit type [ as base ] optional ] optional

[ let-binding | let-rec bindings ] zero-or-more

[ do-statement ] zero-or-more

[ abstract-binding | member-binding | interface-implementation ] zero-or-more

Later sections cover inheritance, abstract bindings, and interface implementations.

The Vector2D in Listing 6-2 uses a construction sequence. Construction sequences can enforce object invariants. For example, the following defines a vector type that checks that its length is close to 1.0 and refuses to construct an instance of the value if not:

/// Vectors whose length is checked to be close to length one.

type UnitVector2D(dx,dy) =

let tolerance = 0.000001

let length = sqrt (dx * dx + dy * dy)

do if abs (length - 1.0) >= tolerance then failwith "not a unit vector";

member v.DX = dx

member v.DY = dy

new() = UnitVector2D (1.0,0.0)

This example shows something else: sometimes it’s convenient for a class to have multiple constructors. You do this by adding extra explicit constructors using a member named new. These must ultimately construct an instance of the object via the primary constructor. The inferred signature for this type contains two constructors:

type UnitVector2D =

class

new : unit -> UnitVector2D

new : dx:float * dy:float -> UnitVector2D

member DX : float

member DY : float

end

This represents a form of method overloading, covered in more detail in the “Adding Method Overloading” section later in this chapter.

Class types can also include static bindings. For example, this can be used to ensure only one vector object is allocated for the Zero and One properties of the vector type:

/// A class including some static bindings

type Vector2D(dx : float, dy : float) =

static let zero = Vector2D(0.0, 0.0)

static let onex = Vector2D(1.0, 0.0)

static let oney = Vector2D(0.0, 1.0)

/// Get the zero vector

static member Zero = zero

/// Get a constant vector along the X axis of length one

static member OneX = onex

/// Get a constant vector along the Y axis of length one

static member OneY = oney

Static bindings in classes are initialized once, along with other module and static bindings in the file. If the class type is generic, it’s initialized once per concrete type generic instantiation.

Adding Further Object Notation to Your Types

As we mentioned, one of the most useful aspects of object programming is the notational convenience of dot-notation. This extends to other kinds of notation, in particular expr.[expr] indexer notation, named arguments, optional arguments, operator overloading, and method overloading. The following sections cover how to define and use these notational conveniences.

Working with Indexer Properties

Like methods, properties can take arguments; these are called indexer properties. The most commonly defined indexer property is called Item, and the Item property on a value v is accessed via the special notation v.[i]. As the notation suggests, these properties are normally used to implement the lookup operation on collection types. The following example implements a sparse vector in terms of an underlying sorted dictionary:

open System.Collections.Generic

type SparseVector(items : seq<int * float>)=

let elems = new SortedDictionary<_,_>()

do items |> Seq.iter (fun (k, v) -> elems.Add(k, v))

/// This defines an indexer property

member t.Item

with get(idx) =

if elems.ContainsKey(idx) then elems.[idx]

else 0.0

You can define and use the indexer property as follows:

> let v = SparseVector [(3, 547.0)];;

val v : SparseVector

> v.[4];;

val it : float = 0.0

> v.[3];;

val it : float = 547.0

You can also use indexer properties as mutable setter properties with the syntax expr.[expr] <- expr. This is covered in the section “Defining Object Types with Mutable State.” Indexer properties can also take multiple arguments; for example, the indexer property for the F# Power Pack type Microsoft.FSharp.Math.Matrix<'T> takes two arguments. Chapter 10 describes this type.

Adding Overloaded Operators

Types can also include the definition of overloaded operators. Typically, you do this by defining static members with the same names as the relevant operators. Here is an example:

type Vector2DWithOperators(dx : float,dy : float) =

member x.DX = dx

member x.DY = dy

static member (+) (v1 : Vector2DWithOperators, v2 : Vector2DWithOperators) =

Vector2DWithOperators(v1.DX + v2.DX, v1.DY + v2.DY)

static member (-) (v1 : Vector2DWithOperators, v2 : Vector2DWithOperators) =

Vector2DWithOperators (v1.DX - v2.DX, v1.DY - v2.DY)

> let v1 = new Vector2DWithOperators (3.0, 4.0);;

val v1 : Vector2DWithOperators

> v1 + v1;;

val it : Vector2DWithOperators = {DX = 6.0; DY = 8.0;}

> v1 - v1;;

val it : Vector2DWithOperators = {DX = 6.0; DY = 8.0;}

If you add overloaded operators to your type, you may also have to customize how generic equality, hashing, and comparison are performed. In particular, the behavior of generic operators such as hash, <, >, <=, >=, compare, min, and max isn’t specified by defining new static members with these names, but rather by the techniques described in Chapter 9.

HOW DOES OPERATOR OVERLOADING WORK?

Using Named and Optional Arguments

The F# object programming constructs are designed largely for use in APIs for software components. Two useful mechanisms in APIs permit callers to name arguments and let API designers make certain arguments optional.

Named arguments are simple. For example, in Listing 6-2, the implementations of some methods specify arguments by name, as in the expression Vector2D(dx=dx+x, dy=dy). You can use named arguments with all dot-notation method calls. Code written using named arguments is often much more readable and maintainable than code relying on argument position. The rest of this book frequently uses named arguments.

You declare a member argument optional by prefixing the argument name with ?. Within a function implementation, an optional argument always has an option<_> type; for example, an optional argument of type int appears as a value of type option<int> within the function body. The value is None if no argument is supplied by the caller and Some(arg) if the argument arg is given by the caller. For example:

open System.Drawing

type LabelInfo(?text : string, ?font : Font) =

let text = defaultArg text ""

let font = match font with

| None -> new Font(FontFamily.GenericSansSerif, 12.0f)

| Some v -> v

member x.Text = text

member x.Font = font

/// Define a static method which creates an instance

static member Create(?text, ?font) = new LabelInfo(?text=text, ?font=font)

The inferred signature for this type shows how the optional arguments have become named arguments accepting option values:

type LabelInfo =

new : ?text:string * ?font:System.Drawing.Font -> LabelInfo

static member Create : ?text:string * ?font:System.Drawing.Font -> LabelInfo

member Font : System.Drawing.Font

member Text : string

You can now create LabelInfo values using several different techniques:

> LabelInfo (text="Hello World");;

val it : LabelInfo = LabelInfo {Font = [Font: Name=Microsoft Sans Serif, Size=12, …];

> LabelInfo("Goodbye Lenin");;

val it : LabelInfo = LabelInfo {Font = [Font: Name=Microsoft Sans Serif, Size=12 …];

> LabelInfo(font = new Font(FontFamily.GenericMonospace, 36.0f),

text = "Imagine");;

val it : LabelInfo = LabelInfo {Font = [Font: Name=Courier New, Size=36, …];

Optional arguments must always appear last in the set of arguments accepted by a method. They’re usually used as named arguments by callers. At the callsite, this is done using the syntax argument-name = argument-value. If the argument has type T option, then argument-value must have type T.

In the example, you see the static member Create which also takes optional arguments, the code for which is repeated below.

type LabelInfo … =

...

/// Define a static method which creates an instance

static member Create(?text, ?font) = new LabelInfo(?text = text, ?font = font)

This represents a common pattern when using optional arguments heavily within a framework implementation: one method taking optional arguments is defined in terms of another. The implementation of the Create method simply passes the optional arguments through to be optional arguments of the constructor. At the callsite, this is done using the syntax ?argument-name = argument-value. Note the extra question mark at the callsite! If the argument has type T option, then argument-value must have type T option as well.

The implementation of LabelInfo uses the F# library function defaultArg, which is a useful way to specify simple default values for optional arguments. Its type is as follows:

val defaultArg : 'T option -> 'T-> 'T

![]() Note The second argument given to the

Note The second argument given to the defaultArg function is evaluated before the function is called. This means you should take care that this argument isn’t expensive to compute and doesn’t need to be disposed. The previous example uses a match expression to specify the default for the font argument for this reason.

Adding Method Overloading

.NET APIs and other object frameworks frequently use a notational device called method overloading. This means a type can support multiple methods with the same name, and uses of methods are distinguished by name, number of arguments, and argument types. For example, the System.Console.WriteLine method of .NET has 19 overloads!

Method overloading is used relatively rarely in F#-authored classes, partly because optional arguments and mutable property setters tend to make it less necessary. However, method overloading is permitted in F#. First, methods can easily be overloaded by the number of arguments. For example, Listing 6-3 shows a concrete type representing an interval of numbers on the number line. It includes two methods called Span, one taking a pair of intervals and the other taking an arbitrary collection of intervals. The overloading is resolved according to argument count.

Listing 6-3. An Interval Type with Overloaded Methods

/// Interval(lo,hi) represents the range of numbers from lo to hi,

/// but not including either lo or hi.

type Interval(lo, hi) =

member r.Lo = lo

member r.Hi = hi

member r.IsEmpty = hi <= lo

member r.Contains v = lo < v && v < hi

static member Empty = Interval(0.0, 0.0)

/// Return the smallest interval that covers both the intervals

/// This method is overloaded.

static member Span (r1 : Interval, r2 : Interval) =

if r1.IsEmpty then r2 else

if r2.IsEmpty then r1 else

Interval(min r1.Lo r2.Lo, max r1.Hi r2.Hi)

/// Return the smallest interval that covers all the intervals

/// This method is overloaded.

static member Span(ranges : seq<Interval>) =

Seq.fold (fun r1 r2 -> Interval.Span(r1, r2)) Interval.Empty ranges

Second, multiple methods can also have the same number of arguments and be overloaded by type. One of the most common examples is providing multiple implementations of overloaded operators on the same type. The following example shows a Point type that supports two subtraction operations, one subtracting a Point from a Point to give a Vector and one subtracting a Vector from a Point to give a Point:

type Vector =

{ DX : float; DY : float }

member v.Length = sqrt( v.DX * v.DX + v.DY * v.DY)

type Point =

{ X : float; Y : float }

static member (-) (p1 : Point, p2 : Point) =

{ DX = p1.X - p2.X; DY = p1.Y - p2.Y }

static member (-) (p : Point, v : Vector) =

{ X = p.X - v.DX; Y = p.Y - v.DY }

Overloads must be unique by signature, and you should take care to make sure your overload set isn’t too ambiguous—the more overloads you use, the more type annotations users of your types will need to add.

Defining Object Types with Mutable State

All the types you’ve seen so far in this chapter have been immutable. For example, the values of the Vector2D types shown in Listing 6-1 and Listing 6-2 can’t be modified after they’re created. Sometimes you may need to define mutable objects, particularly because object programming is a generally useful technique for encapsulating mutable and evolving state. Listing 6-4 shows the definition of a mutable representation of a 2D vector.

Listing 6-4. An Object Type with State

type MutableVector2D(dx : float, dy : float) =

let mutable currDX = dx

let mutable currDY = dy

member vec.DX with get() = currDX and set v = currDX <- v

member vec.DY with get() = currDY and set v = currDY <- v

member vec.Length

with get () = sqrt (currDX * currDX + currDY * currDY)

and set len =

let theta = vec.Angle

currDX <- cos theta * len

currDY <- sin theta * len

member vec.Angle

with get () = atan2 currDY currDX

and set theta =

let len = vec.Length

currDX <- cos theta * len

currDY <- sin theta * len

The mutable state is held in two mutable local let bindings for currDX and currDY. It also exposes additional settable properties, Length and Angle, that interpret and adjust the underlying currDX/currDY values. Here is the inferred signature for the type:

type MutableVector2D =

class

new : dx:float * dy:float -> MutableVector2D

member Angle : float

member DX : float

member DY : float

member Length : float

member Angle : float with set

member DX : float with set

member DY : float with set

member Length : float with set

end

You can use this type as follows:

> let v = MutableVector2D(3.0, 4.0);;

val v : MutableVector2D

> (v.DX, v.DY);;

val it : float * float = (3.0, 4.0)

> (v.Length, v.Angle);;

val it : float * float = (5.0, 0.927295218)

> v.Angle <- System.Math.PI / 6.0;; // "30 degrees"

> (v.DX, v.DY);;

val it : float * float = (4.330127019, 2.5)

> (v.Length, v.Angle);;

val it : float * float = (5.0, 0.523598775)

Adjusting the Angle property rotates the vector while maintaining its overall length. This example uses the long syntax for properties, where you specify both set and get operations for the property.

If the type has an indexer (Item) property, then you write an indexed setter as follows:

open System.Collections.Generic

type IntegerMatrix(rows : int, cols : int)=

let elems = Array2D.zeroCreate<int> rows cols

/// This defines an indexer property with getter and setter

member t.Item

with get (idx1, idx2) = elems.[idx1, idx2]

and set (idx1, idx2) v = elems.[idx1, idx2] <- v

![]() Note Class types with a primary constructor are useful partly because they implicitly encapsulate internal functions and mutable state. This is because all the construction arguments and

Note Class types with a primary constructor are useful partly because they implicitly encapsulate internal functions and mutable state. This is because all the construction arguments and let bindings are private to the object instance being constructed. This is just one of the ways of encapsulating information in F# programming. Chapter 7 covers encapsulation more closely.

OBJECTS AND MUTATION

Using Optional Property Settings

Throughout this book, you’ve used a second technique to specify configuration parameters when creating objects: initial property settings for objects. For example, in Chapter 2, you used the following code:

open System.Windows.Forms

let form = new Form(Visible = true, TopMost = true, Text = "Welcome to F#")

The constructor for the System.Windows.Forms.Form class takes no arguments, so in this case the named arguments indicate set operations for the given properties. The code is shorthand for this:

open System.Windows.Forms

let form =

let tmp = new Form()

tmp.Visible <- true

tmp.TopMost <- true

tmp.Text <- "Welcome to F#"

tmp

The F# compiler interprets unused named arguments as calls that set properties of the returned object. This technique is widely used for mutable objects that evolve over time, such as graphical components, because it greatly reduces the number of optional arguments that need to be plumbed around.

Here’s how to define a version of the LabelInfo type used earlier that is configurable by optional property settings:

open System.Drawing

type LabelInfoWithPropertySetting() =

let mutable text = "" // the default

let mutable font = new Font(FontFamily.GenericSansSerif, 12.0f)

member x.Text with get() = text and set v = text <- v

member x.Font with get() = font and set v = font <- v

> LabelInfoWithPropertySetting(Text="Hello World");;

let form = new Form(Visible = true, TopMost = true, Text = "Welcome to F#")

The “Defining Object Types with Mutable State” section later in this chapter covers mutable objects in more detail.

Declaring Auto-Properties

When declaring properties, especially settable ones, a common pattern occurs where the property storage is defined, the initial value for the property is specified, and the member to allow external access to the property is defined. This has a more convenient syntactic declaration form called an auto-property. An auto-property declaration has the form member val id = expr followed by an optional with get,set if the property storage is mutable and a property setter should be exported. An example is shown below, defining the same type as above.

type LabelInfoWithPropertySetting() =

member val Name = "label"

member val Text = "" with get, set

member val Font = new Font(FontFamily.GenericSansSerif, 12.0f) with get, set

Note that the initializer for an auto-property is executed once per object, when the object is initialized. Auto-properties can also be static.

Getting Started with Object Interface Types

So far in this chapter, you’ve seen only how to define concrete object types. One of the key advances in both functional and object-oriented programming has been the move toward using abstract types for large portions of modern software. These values are typically accessed via interfaces, and you now look at defining new object interface types.

The notion of an object interface type can sound a little daunting at first, but the concept is actually simple; object interface types are ones whose member implementations can vary from value to value. As it happens, you’ve already met one important family of types whose implementations also vary from value to value: F# function types!

You’ve also already met some other important object interface types such as System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerable<'T> and System.IDisposable. .NET object interface types always begin with the letter I.

Object interface types are always implemented, and the type definition itself doesn’t specify how this is done. Listing 6-5 shows an object interface type IShape and a number of implementations of it. This section walks through the definitions in this code piece by piece, because they illustrate the key concepts behind object interface types and how they can be implemented.

Listing 6-5. An Object Interface Type IShape and Some Implementations

open System.Drawing

type IShape =

abstract Contains : Point -> bool

abstract BoundingBox : Rectangle

let circle (center : Point, radius : int) =

{ new IShape with

member x.Contains(p : Point) =

let dx = float32 (p.X - center.X)

let dy = float32 (p.Y - center.Y)

sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy) <= float32 radius

member x.BoundingBox =

Rectangle(

center.X - radius, center.Y - radius,

2 * radius + 1, 2 * radius + 1)}

let square (center : Point, side : int) =

{ new IShape with

member x.Contains(p : Point) =

let dx = p.X - center.X

let dy = p.Y - center.Y

abs(dx) < side / 2 && abs(dy) < side / 2

member x.BoundingBox =

Rectangle(center.X - side, center.Y - side, side * 2, side * 2)}

type MutableCircle() =

member val Center = Point(x = 0, y = 0) with get, set

member val Radius = 10 with get, set

member c.Perimeter = 2.0 * System.Math.PI * float c.Radius

interface IShape with

member c.Contains(p : Point) =

let dx = float32 (p.X - c.Center.X)

let dy = float32 (p.Y - c.Center.Y)

sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy) <= float32 c.Radius

member c.BoundingBox =

Rectangle(

c.Center.X - c.Radius, c.Center.Y - c.Radius,

2 * c.Radius + 1, 2 * c.Radius + 1)

Defining New Object Interface Types

The key definition in Listing 6-5 is the following (it also uses Rectangle and Point, two types from the System.Drawing namespace):

open System.Drawing

type IShape =

abstract Contains : Point -> bool

abstract BoundingBox : Rectangle

Here you use the keyword abstract to define the member signatures for this type, indicating that the implementation of the member may vary from value to value. Also note that IShape isn’t concrete; it’s neither a record nor a discriminated union or class type. It doesn’t have any constructors and doesn’t accept any arguments. This is how F# infers that it’s an object interface type.

Implementing Object Interface Types Using Object Expressions

The following code from Listing 6-5 implements the object interface type IShape using an object expression:

let circle(center : Point, radius : int) =

{ new IShape with

member x.Contains(p : Point) =

let dx = float32 (p.X - center.X)

let dy = float32 (p.Y - center.Y)

sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy) <= float32 radius

member x.BoundingBox =

Rectangle(

center.X - radius, center.Y - radius,

2 * radius + 1, 2 * radius + 1)}

The type of the function circle is as follows:

The construct in the braces, { new IShape with ... }, is the object expression. This is a new expression form that you haven’t encountered previously in this book, because it’s generally used only when implementing object interface types. An object expression must give implementations for all the members of an object interface type. The general form of this kind of expression is simple:

{ new Type optional-arguments with

member-definitions

optional-extra-interface-definitions }

The member definitions take the same form as members for type definitions described earlier in this chapter. The optional arguments are given only when object expressions inherit from a class type, and the optional interface definitions are used when implementing additional interfaces that are part of a hierarchy of object interface types.

You can use the function circle as follows:

> let bigCircle = circle(Point(0, 0), 100);;

val bigCircle : IShape

> bigCircle.BoundingBox;;

val it : Rectangle = {X=-100,Y=-100,Width=201,Height=201}

> bigCircle.Contains(Point(70, 70));;

val it : bool = true

> bigCircle.Contains(Point(71, 71));;

val it : bool = false

Listing 6-5 also contains another function square that gives a different implementation for IShape, also using an object expression:

> let smallSquare = square(Point(1, 1), 1);;

val smallSquare : IShape

> smallSquare.BoundingBox;;

val it : Rectangle = {X=0,Y=0,Width=2,Height=2}

> smallSquare.Contains(Point(0,0));;

val it : bool = false

![]() Note In object-oriented languages, implementing types in multiple ways is commonly called polymorphism, which you may call polymorphism of implementation. Polymorphism of this kind is present throughout F#, and not just with respect to the object constructs. In functional programming, the word polymorphism is used to mean generic type parameters. These are an orthogonal concept discussed in Chapters 2 and 5.

Note In object-oriented languages, implementing types in multiple ways is commonly called polymorphism, which you may call polymorphism of implementation. Polymorphism of this kind is present throughout F#, and not just with respect to the object constructs. In functional programming, the word polymorphism is used to mean generic type parameters. These are an orthogonal concept discussed in Chapters 2 and 5.

Implementing Object Interface Types Using Concrete Types

It’s common to have concrete types that both implement one or more object interface types and provide additional services of their own. Collections are a primary example, because they always implement IEnumerable<'T>. To give another example, in Listing 6-5 the type MutableCircle is defined as follows:

type MutableCircle() =

let radius = 0

member val Center = Point(x = 0, y = 0) with get, set

member val Radius = radius with get, set

member c.Perimeter = 2.0 * System.Math.PI * float radius

interface IShape with

member c.Contains(p : Point) =

let dx = float32 (p.X - c.Center.X)

let dy = float32 (p.Y - c.Center.Y)

sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy) <= float32 c.Radius

member c.BoundingBox =

Rectangle(

c.Center.X - c.Radius, c.Center.Y - c.Radius,

2 * c.Radius + 1, 2 * c.Radius + 1)

This type implements the IShape interface, which means MutableCircle is a subtype of IShape, but it also provides three properties—Center, Radius, and Perimeter—that are specific to the MutableCircle type, two of which are settable. The type has the following signature:

type MutableCircle =

interface IShape

new : unit -> MutableCircle

member Perimeter : float

member Center : Point with get,set

member Radius : int with get,set

You can now reveal the interface (through a type cast) and use its members. For example:

> let circle2 = MutableCircle();;

val circle2 : MutableCircle

> circle2.Radius;;

val it : int = 10

> (circle2 :> IShape).BoundingBox;;

val it : Rectangle = {X=-10,Y=-10,Width=21,Height=21}

Using Common Object Interface Types from the .NET Libraries

Like other constructs discussed in this chapter, object interface types are often encountered when using .NET libraries. Some object interface types such as IEnumerable<'T> (called seq<'T> in F# coding) are also used throughout F# programming. It’s a .NET convention to prefix the name of all object interface types with I. However, using object interface types is very common in F# object programming, so this convention isn’t always followed.

Here’s the essence of the definition of the System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerable<'T> type and the related type IEnumerator using F# notation:

type IEnumerator<'T> =

abstract Current : 'T

abstract MoveNext : unit -> bool

type IEnumerable<'T> =

abstract GetEnumerator : unit -> IEnumerator<'T>

The IEnumerable<'T> type is implemented by most concrete collection types. It can also be implemented by a sequence expression or by calling a library function such as Seq.unfold, which in turn uses an object expression as part of its implementation.

![]() Note The

Note The IEnumerator<'T> and IEnumerable<'T> interfaces are defined in a library component that is implemented using another .NET language. This section uses the corresponding F# syntax. In reality, IEnumerator<'T> also inherits from the nongeneric interface System.Collections.IEnumerator and the type System.IDisposable, and IEnumerable<'T> also inherits from the nongeneric interface System.Collections.IEnumerable. For clarity, we’ve ignored this. See the F# library documentation for full example implementations of these types.

Some other useful predefined F# and .NET object interface types are as follows:

System.IDisposable: Represents values that may own explicitly reclaimable resources.System.IComparableandSystem.IComparable<'T>: Represent values that can be compared to other values. F# generic comparison is implemented via these types, as you see in Chapter 9.Microsoft.FSharp.Control.IEvent: Represents mutable ports into which you can plug event listeners, or callbacks. This technique is described in Chapter 11. Some other entity is typically responsible for raising the event and thus calling all the listener callbacks. In F#, .NET events become values of this type or the related typeMicrosoft.FSharp.Control.IDelegateEvent, and the moduleMicrosoft.FSharp.Control.Eventcontains many useful functions for manipulating these values. You can open this module by usingopen Event.

Understanding Hierarchies of Object Interface Types

Object interface types can be arranged in hierarchies using interface inheritance. This provides a way to classify types. To create a hierarchy, you use the inherit keyword in an object interface type definition along with each parent object interface type. For example, the .NET Framework includes a hierarchical classification of collection types: ICollection<'T> extends IEnumerable<'T>. Here are the essential definitions of these types in F# syntax, with some minor details omitted:

type IEnumerable<'T> =

abstract GetEnumerator : unit -> IEnumerator<'T>

type ICollection<'T> =

inherit IEnumerable<'T>

abstract Count : int

abstract IsReadOnly : bool

abstract Add : 'T -> unit

abstract Clear : unit -> unit

abstract Contains : 'T -> bool

abstract CopyTo : 'T [] * int -> unit

abstract Remove : 'T -> unit

When you implement an interface that inherits from another interface, you must effectively implement both interfaces.

![]() Caution Although hierarchical modeling is useful, you must use it with care: poorly designed hierarchies often have to be abandoned late in the software development life cycle, leading to major disruptions. For many applications, it’s adequate to use existing classification hierarchies in conjunction with some new nonhierarchical interface types.

Caution Although hierarchical modeling is useful, you must use it with care: poorly designed hierarchies often have to be abandoned late in the software development life cycle, leading to major disruptions. For many applications, it’s adequate to use existing classification hierarchies in conjunction with some new nonhierarchical interface types.

More Techniques to Implement Objects

Objects can be difficult to implement from scratch; for example, a graphical user interface (GUI) component must respond to many different events, often in regular and predictable ways, and it would be tedious to have to recode all this behavior for each component. This makes it essential to support the process of creating partial implementations of objects, where the partial implementations can then be completed or customized. The following sections cover techniques to build partial implementations of objects.

Combining Object Expressions and Function Parameters

One of the easiest ways to build a partial implementation of an object is to qualify the implementation of the object by a number of function parameters that complete the implementation. For example, the following code defines an object interface type called ITextOutputSink, a partial implementation of that type called simpleOutputSink, and a function called simpleOutputSink that acts as a partial implementation of that type. The remainder of the implementation is provided by a function parameter called writeCharFunction:

/// An object interface type that consumes characters and strings

type ITextOutputSink =

/// When implemented, writes one Unicode character to the sink

abstract WriteChar : char -> unit

/// When implemented, writes one Unicode string to the sink

abstract WriteString : string -> unit

/// Returns an object that implements ITextOutputSink by using writeCharFunction

let simpleOutputSink writeCharFunction =

{ new ITextOutputSink with

member x.WriteChar(c) = writeCharFunction c

member x.WriteString(s) = s |> String.iter x.WriteChar }

This construction function uses function values to build an object of a given shape. Here the inferred type is as follows:

val simpleOutputSink : writeCharFunction:(char -> unit) -> ITextOutputSink

The following code instantiates the function parameter to output the characters to a particular System.Text.StringBuilder object, an imperative type for accumulating characters in a buffer before converting these to an immutable System.String value:

let stringBuilderOuputSink (buf : System.Text.StringBuilder ) =

simpleOutputSink (fun c -> buf.Append(c) |> ignore)

Here is an example that uses this function interactively:

> let buf = new System.Text.StringBuilder();;

val buf : StringBuilder =

> let c = stringBuilderOuputSink(buf);;

val c : ITextOutputSink

> ["Incy"; " "; "Wincy"; " "; "Spider"] |> List.iter c.WriteString;;

> buf.ToString();;

val it : string = "Incy Wincy Spider"

Object expressions must give definitions for all unimplemented abstract members and can’t add other members.

One powerful technique implements some or all abstract members in terms of function parameters. As you saw in Chapter 3, function parameters can represent a wide range of concepts. For example, here is a type CountingOutputSink that performs the same role as the earlier function simpleOutputSink, except that the number of characters written to the sink is recorded and published as a property:

/// A type which fully implements the ITextOutputSink object interface

type CountingOutputSink(writeCharFunction : char -> unit) =

let mutable count = 0

interface ITextOutputSink with

member x.WriteChar(c) = count <- count + 1; writeCharFunction(c)

member x.WriteString(s) = s |> String.iter (x :> ITextOutputSink).WriteChar

member x.Count = count

![]() Note Qualifying object implementations by function parameters can be seen as a simple form of the OO design pattern known as delegation, because parts of the implementation are delegated to the function values. Delegation is a powerful and compositional technique for reusing fragments of implementations and is commonly used in F# as a replacement for OO implementation inheritance.

Note Qualifying object implementations by function parameters can be seen as a simple form of the OO design pattern known as delegation, because parts of the implementation are delegated to the function values. Delegation is a powerful and compositional technique for reusing fragments of implementations and is commonly used in F# as a replacement for OO implementation inheritance.

Defining Partially Implemented Class Types

In this chapter, you’ve seen how to define concrete types, such as Vector2D in Listings 6-2 and 6-3, and you’ve seen how to define object interface types, such as IShape in Listing 6-5. Sometimes it’s useful to define types that are halfway between these types: partially concrete types. Partially implemented types are class types that also have abstract members, some of which may be unimplemented and some of which may have default implementations. For example, consider the following class:

/// A type whose members are partially implemented

[<AbstractClass>]

type TextOutputSink() =

abstract WriteChar : char -> unit

abstract WriteString : string -> unit

default x.WriteString s = s |> String.iter x.WriteChar

This class defines two abstract members, WriteChar and WriteString, but gives a default implementation for WriteString in terms of WriteChar. (In C# terminology, WriteString is virtual and WriteChar is abstract). Because WriteChar isn’t yet implemented, you can’t create an instance of this type directly; unlike other concrete types, partially implemented types still need to be implemented. One way to do this is to complete the implementation via an object expression. For example:

{ new TextOutputSink() with

member x.WriteChar c = System.Console.Write(c)}

Using Partially Implemented Types via Delegation

This section covers how you can use partially implemented types to build complete objects. One approach is to instantiate one or more partially implemented types to put together a complete concrete type. This is often done via delegation to an instantiation of the partially concrete type; for example, the following example creates a private, internal TextOutputSink object whose implementation of WriteChar counts the number of characters written through that object. You use this object to build the HtmlWriter object that publishes three methods specific to the process of writing a particular format:

/// A type which uses a TextOutputSink internally

type HtmlWriter() =

let mutable count = 0

let sink =

{ new TextOutputSink() with

member x.WriteChar c =

count <- count + 1;

System.Console.Write c }

member x.CharCount = count

member x.OpenTag(tagName) = sink.WriteString(sprintf "<%s>" tagName)

member x.CloseTag(tagName) = sink.WriteString(sprintf "</%s>" tagName)

member x.WriteString(s) = sink.WriteString(s)

Using Partially Implemented Types via Implementation Inheritance

Another technique to use partially implemented types is called implementation inheritance, which is widely used in OO languages despite being a somewhat awkward technique. Implementation inheritance tends to be much less significant in F# because it comes with major drawbacks:

- Implementation inheritance takes base objects and makes a new type that is more complex, by adding new members. This is against the spirit of functional programming, where the aim is to build simple, composable abstractions. Functional programming, object expressions, and delegation tend to provide good alternative techniques for defining, sharing, and combining implementation fragments.

- Implementation hierarchies tend to leak across API boundaries, revealing how objects are implemented rather than how they can be used and composed.

- Implementation hierarchies are often fragile in response to minor changes in program specification. There is pressure on developers to put too much functionality in base classes, anticipiating the needs of all derivations. There’s also pressure to go back and change the base class as new needs arise. This gives rise the the “fragile base class” problem, a major curse of object-oriented programming.

If implementation inheritance is used, you should in many cases consider making all implementing classes private or hiding all implementing classes behind a signature. For example, the Microsoft.FSharp.Collections.Seq module provides many implementations of the seq<'T> interface but exposes no implementation inheritance.

Nevertheless, hierarchies of classes are important in domains such as GUI programming, and the technique is used heavily by .NET libraries written in other .NET languages. For example, System.Windows.Forms.Control, System.Windows.Forms.UserControl, and System.Windows.Forms.RichTextBox are part of a hierarchy of visual GUI elements. Should you want to write new controls, then you must understand this implementation hierarchy and how to extend it. However, even in this domain, implementation inheritance is often less important than you may think, because these controls can often be configured in powerful and interesting ways by adding function callbacks to events associated with the controls.

Here is a simple example of applying the technique to instantiate and extend the partially implemented type TextOutputSink:

/// An implementation of TextOutputSink, counting the number of bytes written

type CountingOutputSinkByInheritance() =

inherit TextOutputSink()

let mutable count = 0

member sink.Count = count

default sink.WriteChar c =

count <- count + 1;

System.Console.Write c

The keywords override and default can be used interchangeably; both indicate that an implementation is being given for an abstract member. By convention, override is used when giving implementations for abstract members in inherited types that already have implementations, and default is used for implementations of abstract members that didn’t previously have implementations.

Implementations are also free to override and modify default implementations such as the implementation of WriteString provided by TextOutputSink. Here is an example:

{ new TextOutputSink() with

member sink.WriteChar c = System.Console.Write c

member sink.WriteString s = System.Console.Write s }

You can also build new partially implemented types by extending existing partially implemented types. The following example takes the TextOutputSink type from the previous section and adds two abstract members called WriteByte and WriteBytes, adds a default implementation for WriteBytes, adds an initial implementation for WriteChar, and overrides the implementation of WriteString to use WriteBytes. The implementations of WriteChar and WriteString use the .NET functionality to convert the Unicode characters and strings to bytes under System.Text.UTF8Encoding, documented in the .NET Framework class libraries:

open System.Text

/// A component to write bytes to an output sink

[<AbstractClass>]

type ByteOutputSink() =

inherit TextOutputSink()

/// When implemented, writes one byte to the sink

abstract WriteByte : byte -> unit

/// When implemented, writes multiple bytes to the sink

abstract WriteBytes : byte[] -> unit

default sink.WriteChar c = sink.WriteBytes(Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes [|c|])

override sink.WriteString s = sink.WriteBytes(Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes s)

default sink.WriteBytes b = b |> Array.iter sink.WriteByte

Combining Functional and Objects: Cleaning Up Resources

Many constructs in the System.IO namespace need to be closed after use, partly because they hold on to operating-system resources such as file handles. This is an example where objects are used to encapsulate and manage resource lifetime. In polished code, you use language constructs such as use val = expr to ensure that the resource is closed at the end of the lexical scope where a stream object is active. For example:

let myWriteStringToFile() =

use outp = File.CreateText("playlist.txt")

outp.WriteLine("Enchanted")

outp.WriteLine("Put your records on")

This is equivalent to the following:

let myWriteStringToFile () =

let outp = File.CreateText("playlist.txt")

try

outp.WriteLine("Enchanted")

outp.WriteLine("Put your records on")

finally

(outp :> System.IDisposable).Dispose()

Both forms ensure that the underlying stream is closed deterministically and the operating system resources are reclaimed when the lexical scope is exited. The longer form uses the :> operator to call Dispose, explained further in Chapter 5. This happens regardless of whether the scope is exited because of normal termination or because of an exception.

![]() Note: If you don’t use

Note: If you don’t use using or otherwise explicitly close the stream, the stream is closed when the stream object is finalized by the .NET garbage collector. It’s generally bad practice to rely on finalization to clean up resources this way, because finalization isn’t guaranteed to happen in a deterministic, timely fashion.

Resources and IDisposable

All programming involves the use of real resources on the host machine(s) and operating system. For example:

- Stack: Implicitly allocated and deallocated as functions are called

- Heap allocated memory: Used by all reference-typed objects

- File handles: Such as operating-system file handles represented by

System.IO.FileStreamobjects and its subtypes- Network connections: Such as operating system I/O completion ports represented by

System.Net.WebResponseand its subtypes- Threads: Such as operating-system threads represented by

System.Threading.Threadobjects and also worker threads in the .NET thread pool- Graphics objects: Such as drawing objects represented by various constructs under the

System.Drawingnamespace- Concurrency objects: Such as operating-system synchronization objects represented by

System.Threading.WaitHandleobjects and its subtypes

All resources are necessarily finite. In .NET programming, some resources such as memory are fully managed, in the sense that you almost never need to consider when to clean up memory. This is done automatically through a process called garbage collection. Chapter 18 looks at garbage collection in more detail. Other resources must be reclaimed and/or recycled.

When prototyping, you can generally assume that resources are unbounded, although it’s good practice when you’re using a resource to be aware of how much of the resource you’re using and roughly what your budget for the resource is. For example:

- On a modern 32-bit desktop machine, 10,000 tuple values occupy only a small fragment of a machine’s memory, roughly 160KB, but 10,000 open file handles is an extreme number and will stress the operating system. Ten thousand simultaneous web requests may stress your network administrator.

- In some cases, even memory should be explicitly and carefully reclaimed. For example, on a modern 64-bit machine, the largest single array you can allocate in a .NET 2.0 program is 2GB. If your machine has, say, 4GB of real memory, you may be able to have only a handful of these objects and should strongly consider moving to a regime in which you explicitly recycle these objects and think carefully before allocating them.

With the exception of stack and memory, all objects that own resources should be subtypes of the .NET type System.IDisposable. This is the primary way you can recognize primitive resources and objects that wrap resources. The System.IDisposable interface has a single method; in F# syntax, it can be defined as:

namespace System

type IDisposable =

abstract Dispose : unit -> unit

A simple approach to managing IDisposable objects is to give each resource a lifetime: that is, some well-defined portion of the program execution for which the object is active. This is even easier when the lifetime of a resource is lexically scoped, such as when a resource is allocated on entry to a function and deallocated on exit. In this case, the resource can be tied to the scope of a particular variable, and you can protect and dispose of a value that implements IDisposable by using a use binding instead of a let binding. For example, in the following code, three values implement IDisposable, all of which are bound using use:

/// Fetch a web page

let http (url : string) =

let req = System.Net.WebRequest.Create url

use resp = req.GetResponse()

use stream = resp.GetResponseStream()

use reader = new System.IO.StreamReader(stream)

let html = reader.ReadToEnd()

html

This is an improved version of the similar function you defined in Chapter 2, because it deterministically closes the network connections. In all three cases, the objects (a WebResponse, a Stream, and a StreamReader) are automatically closed and disposed at the end of an execution of the function.

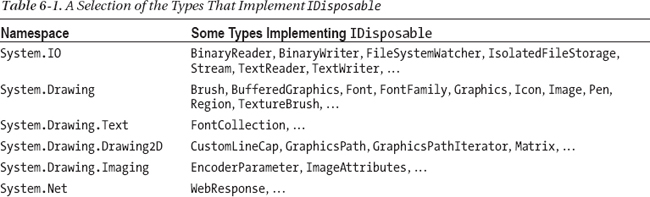

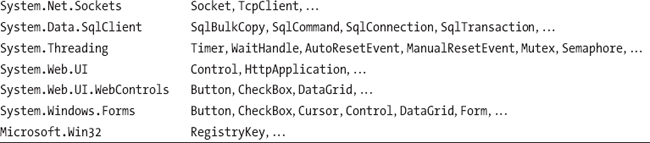

A number of important types implement IDisposable; Table 6-1 shows some of them. You can use tables such as this to chart the portions of the .NET Framework that reveal operating system functionality to .NET applications.

![]() Tip: A tool such as Visual Studio can help you determine when a type has implemented

Tip: A tool such as Visual Studio can help you determine when a type has implemented IDisposable. When you rest your mouse pointer over a value, you usually see this noted on the information displayed for a value.

WHEN WILL THE RUNTIME CLEAN UP FOR YOU?

Managing Resources with More Complex Lifetimes

Sometimes, the lifetime of a resource isn’t simple in the sense that it doesn’t follow a stack discipline. In these cases, you should almost always adopt one of two techniques:

- Design objects that can own one or more resources and that are responsible for cleaning them up. Make sure these objects implement

System.IDisposable.- Use control constructs that help you capture the kind of computation you’re performing. For example, when generating sequences of data (such as from a database connection), you should strongly consider using sequence expressions, discussed in Chapter 3. These may have internal

usebindings, and the resources are disposed when each sequence iteration finishes. Likewise, when using asynchronous I/O, it may be helpful to write your computation as an asynchronous workflow. Chapter 11 and the following sections provide examples.

Consider implementing theIDisposableinterface on objects and types in situations such as:- When you build an object that uses one or more

IDisposableobjects internally.- When you’re writing a wrapper for an operating-system resource or some resource allocated and managed in a native (C or C++) DLL. In this case, implement a finalizer by overriding the

Object.Finalizemethod.- When you implement the

System.Collections.Generic.IEnumerable<'T>(that is, sequence) interface on a collection. TheIEnumerableinterface isn’tIDisposable, but it must generateSystem.Collection.Generic.IEnumerator<'T>values, and this interface inherits fromIDisposable. For nearly all collection types, the disposal action returns without doing anything.

The following sections give some examples of these.

Cleaning Up Internal Objects

Listing 6-6 shows an example that implements an object that reads lines from a pair of text files, choosing the file at random at each line pull. You must implement the type IDisposable, because the object owns two internal System.IO.StreamReader objects, which are IDisposable. You also must explicitly check to see whether the object has already been disposed.

Listing 6-6. Implementing IDisposable to Clean Up Internal Objects

open System.IO

type LineChooser(fileName1, fileName2) =

let file1 = File.OpenText(fileName1)

let file2 = File.OpenText(fileName2)

let rnd = new System.Random()

let mutable disposed = false

let cleanup() =

if not disposed then

disposed <- true;

file1.Dispose();

file2.Dispose();

interface System.IDisposable with

member x.Dispose() = cleanup()

member obj.CloseAll() = cleanup()

member obj.GetLine() =

if not file1.EndOfStream &&

(file2.EndOfStream || rnd.Next() % 2 = 0) then file1.ReadLine()

elif not file2.EndOfStream then file2.ReadLine()

else raise (new EndOfStreamException())

You can now instantiate, use, and dispose of this object as follows:

> open System; open System.IO;;

> File.WriteAllLines("test1.txt", [|"Daisy, Daisy"; "Give me your hand oh do"|]);;

> File.WriteAllLines("test2.txt", [|"I'm a little teapot"; "Short and stout"|]);;

> let chooser = new LineChooser ("test1.txt", "test2.txt");;

val chooser : LineChooser

> chooser.GetLine();;

val it : string = "Daisy, Daisy"

> chooser.GetLine();;

val it : string = "I'm a little teapot"

> (chooser :> IDisposable).Dispose();;

> chooser.GetLine();;

System.ObjectDisposedException: Cannot read from a closed TextReader.

Disposal should leave an object in an unusable state, as shown in the last line of the previous example. It’s also common for objects to implement a member with a more intuitive name that does precisely the same thing as its implementation of IDisposable.Dispose, which is CloseAll in Listing 6-6.

Cleaning Up Unmanaged Objects

If you’re writing a component that explicitly wraps some kind of unmanaged resource, then implementing IDisposable is a little trickier. Listing 6-7 shows the pattern that is used for this cleanup. Here, you mimic an external resource via a data structure that generates fresh, reclaimable integer tickets. The idea is that each customer is given an integer ticket, but this is kept internal to the customer, and customers return their tickets to the pool when they leave (that is, are disposed).

Listing 6-7. Reclaiming Unmanaged Tickets with IDisposable

open System

type TicketGenerator() =

let mutable free = []

let mutable max = 0

member h.Alloc() =

match free with

| [] -> max <- max + 1; max

| h :: t -> free <- t; h

member h.Dealloc(n:int) =

printfn "returning ticket %d" n

free <- n :: free

let ticketGenerator = new TicketGenerator()

type Customer() =

let myTicket = ticketGenerator.Alloc()

let mutable disposed = false

let cleanup() =

if not disposed then

disposed <- true

ticketGenerator.Dealloc(myTicket)

member x.Ticket = myTicket

interface IDisposable with

member x.Dispose() = cleanup(); GC.SuppressFinalize(x)

override x.Finalize() = cleanup()

Note that you override the Object.Finalize method. This makes sure cleanup occurs if the object isn’t disposed but is still garbage-collected. If the object is explicitly disposed, you call GC.SuppressFinalize() to ensure that the object isn’t later finalized. The finalizer shouldn’t call the Dispose() of other managed objects, because they have their own finalizers if needed. The following example session generates some customers, and tickets used by some of the customers are automatically reclaimed as they exit their scopes:

> let bill = new Customer();;

val bill : Customer

> bill.Ticket;;

val it : int = 1

> begin

use joe = new Customer()

printfn "joe.Ticket = %d" joe.Ticket

end;;

joe.Ticket = 2

returning ticket 2

> begin

use jane = new Customer()

printfn "jane.Ticket = %d" jane.Ticket

end;;

jane.Ticket = 2

returning ticket 2

In the example, Joe and Jane get the same ticket. Joe’s ticket is returned at the end of the scope where the joe variable is declared because of the IDisposable cleanup implicit in the use binding.

Extending Existing Types and Modules

The final topic covered in this chapter is how you can define ad hoc dot-notation extensions to existing library types and modules. This technique is used rarely but can be invaluable in certain circumstances. For example, the following definition adds the member IsPrime to Int32.

module NumberTheoryExtensions =

let isPrime i =

let lim = int (sqrt (float i))

let rec check j =

j > lim || (i % j <> 0 && check (j + 1))

check 2

type System.Int32 with

member i.IsPrime = isPrime i

The IsPrime property is then available for use in conjunction with int32 values whenever the NumberTheoryExtensions module has been opened. (Note, F# extension members are very similar to C# extension methods). For example:

> open NumberTheoryExtensions;;

> (2 + 1).IsPrime;;

val it : bool = true

> (6093700 + 11).IsPrime;;

val it : bool = false

Type extensions can be given in any assembly, but priority is always given to the intrinsic members of a type when resolving dot-notation.

Modules can also be extended in a fashion. For example, say you think the List module is missing an obvious function such as List.pairwise to return a new list of adjacent pairs. You can extend the set of values accessed by the path List by defining a new module List:

module List =

let rec pairwise l =

match l with

| [] | [_] -> []

| h1 :: ((h2 :: _) as t) -> (h1, h2) :: pairwise t

> List.pairwise [1; 2; 3; 4];;

val it : (int * int) list = [(1,2); (2,3); (3,4)]

![]() Note Type extensions are a good technique for equipping simple type definitions with extra functionality. However, don’t fall into the trap of adding too much functionality to an existing type via this route. Instead, it’s often simpler to use additional modules and types. For example, the module

Note Type extensions are a good technique for equipping simple type definitions with extra functionality. However, don’t fall into the trap of adding too much functionality to an existing type via this route. Instead, it’s often simpler to use additional modules and types. For example, the module Microsoft.FSharp.Collections.List contains extra functionality associated with the F# list type.

USING MODULES AND TYPES TO ORGANIZE CODE

Working with F# Objects and .NET Types

This chapter has deemphasized the use of .NET terminology for object types, such as class and interface. However, all F# types are ultimately compiled as .NET types. Here is how they relate:

- Concrete types such as record types, discriminated unions, and class types are compiled as .NET classes.

- Object interface types are by default compiled as .NET interface types.

If you want, you can delimit class types using class/end:

type Vector2D(dx : float, dy : float) =

class

let len = sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy)

member v.DX = dx

member v.DY = dy

member v.Length = len

end

or you can use a Class attribute:

[<Class>]

type Vector2D(dx : float, dy : float) =

let len = sqrt(dx * dx + dy * dy)

member v.DX = dx

member v.DY = dy

member v.Length = len

You see this in F# code samples on the Web and in other books. However, we have found that this tends to make types harder to understand, so we’ve omitted class/end and Class attributes throughout this book. You can also delimit object interface types by interface/end:

type IShape =

interface

abstract Contains : Point -> bool

abstract BoundingBox : Rectangle

end

or you can use an attribute:

[<Interface>]

type IShape =

abstract Contains : Point -> bool

abstract BoundingBox : Rectangle

Again, we omit these attributes in this book.

Structs

It’s occasionally useful to direct the F# compiler to use a .NET struct (value type) representation for small, generally immutable objects. You can do this by adding a Struct attribute to a class type and adding type annotations to all arguments of the primary constructor:

[<Struct>]

type Vector2DStruct(dx : float, dy : float) =

member v.DX = dx

member v.DY = dy

member v.Length = sqrt (dx * dx + dy * dy)

Finally, you can also use a form that makes the values held in a struct explicit:

[<Struct>]

type Vector2DStructUsingExplicitVals =

val dx : float

val dy : float

member v.DX = v.dx

member v.DY = v.dy

member v.Length = sqrt (v.dx * v.dx + v.dy * v.dy)

Structs are often more efficient, but you should use them with care because the full contents of struct values are frequently copied. The performance characteristics of structs can also change depending on whether you’re running on a 32-bit or 64-bit machine.

Delegates

Occasionally, you need to define a new .NET delegate type in F#:

type ControlEventHandler = delegate of int -> bool

This is usually required only when using C code from F#, because some magic performed by the .NET Common Language Runtime lets you marshal a delegate value as a C function pointer. Chapter 18 looks at interoperating with C and COM. For example, here’s how you add a new handler to the Win32 Ctrl+C–handling API:

open System.Runtime.InteropServices

let ctrlSignal = ref false

[<DllImport("kernel32.dll")>]

extern void SetConsoleCtrlHandler(ControlEventHandler callback, bool add)

let ctrlEventHandler = new ControlEventHandler(fun i -> ctrlSignal := true; true)

SetConsoleCtrlHandler(ctrlEventHandler,true)

Enums

Occasionally, you need to define a new .NET enum type in F#. You do this using a notation similar to discriminated unions:

type Vowels =

| A = 1

| E = 5

| I = 9

| O = 15

| U = 21

This type is compiled as a .NET enum whose underlying bit representation is a simple integer. Likewise, you can define enums for other .NET primitive types such as byte, int64 and uint64.

Working with null Values

The keyword null is used in programming languages as a special, distinguished value of a type that represents an uninitialized value or some other kind of special condition. In general, null isn’t used in conjunction with types defined in F# code, although it’s common to simulate null with a value of the option type. For example:

> let parents = [("Adam", None); ("Cain", Some("Adam", "Eve"))];;

val parents : (string * (string * string) option) list = ...

Reference types defined in other .NET languages do support null, however; when using .NET APIs, you may have to explicitly pass null values to the API and also, where appropriate, test return values for null. The .NET Framework documentation specifies when null may be returned from an API. It’s recommended that you test for this condition using null value tests. For example:

match System.Environment.GetEnvironmentVariable("PATH") with

| null -> printf "the environment variable PATH is not defined

"

| res -> printf "the environment variable PATH is set to %s

" res

The following is a function that incorporates a pattern match with type tests and a null-value test:

let switchOnType (a : obj) =

match a with

| null -> printf "null!"

| :? System.Exception as e -> printf "An exception: %s!" e.Message

| :? System.Int32 as i -> printf "An integer: %d!" i

| :? System.DateTime as d -> printf "A date/time: %O!" d

| _ -> printf "Some other kind of object

"

There are other important sources of null values. For example, the semisafe function Array.zeroCreate creates an array whose values are initially null or, in the case of value types, an array each of whose entries is the zero bit pattern. This function is included with F# primarily because there is no other technique for initializing and creating the array values used as building blocks of larger, more sophisticated data structures, such as queues and hash tables. Of course, you must use this function with care, and in general you should hide the array behind an encapsulation boundary and be sure the values of the array aren’t referenced before they’re initialized.

![]() Note: Although F# generally enables you to code in a

Note: Although F# generally enables you to code in a null-free style, F# isn’t totally immune to the potential existence of null values: they can come from the .NET APIs, and it’s also possible to use Array.zeroCreate and other back-door techniques to generate null values for F# types. If necessary, APIs can check for this condition by first converting F# values to the obj type by calling box and then testing for null (see the F# Informal Language Specification for full details). In practice, this isn’t required by the vast majority of F# programs; for most purposes, the existence of null values can be ignored.

Summary

This chapter looked at the basic constructs of object-oriented programming in F#, including concrete object types, object notation, and object interface types and their implementations, as well as more advanced techniques to implement object interface types. You also saw how implementation inheritance is less important as an object implementation technique in F# than in other object-oriented languages and then learned how the F# object model relates to the .NET object model. The next chapter covers language constructs and practical techniques related to encapsulating, packaging, and deploying your code.