1 Herbert Zettl, Approaches to Building Screen Space and Vectors

Approaches to Building Screen Space

Our first approach to understanding how editing creates meaning is to set aside the usual narrative functions of editing – the story the film is trying to tell, the notion of coverage, the need to shape dialogue scenes – and simply consider the film image as a two-dimensional screen space, a combination of interacting visual elements enclosed by a frame. With his background in gestalt psychology and art theory, Rudolf Arnheim (1904–2007) laid the groundwork for this approach in the early period of classic film theory with his seminal text Film as art first published in 1933. There are few theorists more central to our understanding of how motion pictures work – indeed how the visual arts work – than Arnheim. He was a profound thinker and gifted writer who could explicate difficult concepts with brilliant clarity. After studying gestalt psychology with Max Wertheimer in Berlin in the 1920s, Arnheim spent most of his life applying its concepts to explain how visual perception works in art.

Gestalt psychology, Arnheim writes,

came about as an amendment to the traditional method of scientific analysis. The accepted way of analyzing complex phenomenon scientifically had been that of describing the parts and arriving at the whole by adding up the descriptions thus obtained. Recent developments in biology, psychology, and sociology had begun to suggest, however, that such a procedure could not do justice to phenomena that are field processes – entities made up of interacting forces.1

Gestalt psychology noticed that the laws governing the physical world are reflected in human visual perception, making it possible to coordinate and map mental functions with the physical world, and ultimately to see art as the expressive, intelligent translation of visual thinking into the creative potentials of a given media. As Arnheim puts it,

even the most elementary processes of vision do not produce mechanical recordings of the outer world but organize the sensory raw material according to principles of simplicity, regularity, and balance, which govern the receptor mechanism [the eyes and the brain structures that control the eyes]. This discovery of the gestalt school fitted the notion that the work of art, too, is not simply an imitation or selective duplication of reality but a translation of observed characteristics into the forms of a given medium.2

Writing in the early 1930s, Arheim agreed with a few early film theorists that the medium of film was not a mechanical recording of the world but rather reshaped reality using its unique potentials. As he put it, “Art begins where mechanical reproduction leaves off, where the conditions of reproduction serve in some way to mold the object.”3 In a brilliant turn of thinking, Arnheim argued that it is precisely the limitations of film – projection of solids onto a plane surface, reduction of depth, framing/limitation of the field of view, etc. – that supply film with its artistic means.

Arnheim lectured on the psychology of art at a number of American universities after World War II, including Sarah Lawrence College, Harvard University and the University of Michigan. Fellowships from the Guggenheim and Rockefeller foundations gave him time to research the application of gestalt theories to the visual arts. His major opus Art and visual perception: a psychology of the creative eye (1954) was followed by Visual thinking (1969), and his scholarly writing continued for decades. With a deep love of art in all its forms, a deep respect for artists, and a deep understanding of the psychology of visual perception and cognition, Rudolf Arnheim – who died in 2007 at the age of 103 – is a towering figure in advancing our understanding of how mind and art interact.

Arnheim’s work was influential in turning public opinion about value of motion pictures. Photography – regarded as a dry, mechanical method for realistically reproducing images – and motion pictures – with their reliance on melodramatic narratives that appealed to the masses – struggled during the early period of their history to be recognized as art forms with unique properties of expression. Against the claim that film is a mechanical medium that merely reproduces reality, Arnheim argued that what makes film an art is its unique formal qualities that make it unreal, or different from reality – its projection of three-dimensional solids on to a two-dimensional screen, its reduction of a sense of depth, the framing of the image, the absence of continuous time because of editing, etc. An often-quoted section of Arnheim’s Film as art argues that:

The effect of film is neither absolutely two-dimensional nor absolutely three-dimensional, but something between. Film pictures are at once plane and solid. . . film gives simultaneously the effect of an actual happening and of a picture. A result of the “pictureness” of film is, then, that a sequence of scenes that are diverse in time and space is not felt as arbitrary. One looks at them as calmly as one would at a collection of picture post cards. Just as it does not disturb us in the least to find different places and different moments in time registered in such pictures, so it does not seem awkward in a film. If at one moment we see a long shot of a woman at the back of a room, and the next we see a close up of her face, we simply feel that we have “turned over a page” and are looking at a fresh picture. If film photographs gave a very strong spatial impression, montage [editing] probably would be impossible. It is the partial unreality of the film picture that makes it possible.4

Thus, the world captured in film is translated by the lens from a three-dimensional space to a two-dimensional screen space, a flat, mediated representation of the world that simultaneously feels like “an actual happening.” According to Arnheim, it is this very trait of film – a mediated space that exhibits both “pictureness” and “actuality” – that makes editing possible.

This screen space presents the audience with a variety of changing visual forces, a rich two-dimensional stimulus set, a visual field that our brains habitually decode using the fundamental gestalt principles our perceptual systems have evolved like laws of grouping which include proximity, symmetry, similarity and closure.5 These characteristics that Arnheim first identified suggest a scheme that we can use to look at how cutting works. Think of a single edit not as a change of shot that might, for example, simply go from a long shot to a close up to cover a character’s reaction, but as one two-dimensional frame full of screen elements and screen forces that changes to another two-dimensional frame full of screen elements and screen forces. As the shot changes, the screen elements may or may not match, the screen forces at work may or may not continue. Thinking this way, in terms of screen space – using the framed, two-dimensional, visual elements that underlie the outgoing shot and comparing them to the same parameters of the incoming shot – turns out to be a valuable tool for evaluating many aspects of the basic question all editors face: does the cut work (or not), and if so why (or why not)? In other words, for the editor, the focus of the analysis becomes a comparison of abstract, visual forces that occur across the cut.

Debates about screen space in classical film theory continued through the 1960s and often revolved around the nature of the film image and of the film frame. Just as Arnheim felt that screen space was “something between,” the frame of the moving image itself was thought to have dual function. Specifically, classical film theorists raised this question: does the frame in motion pictures function primarily to formalize the elements within it or does it function more like a window, selecting what the viewer sees while simultaneously recognizing that action spills out beyond its edges?6

In the first case – the formalizing function of the frame – the director uses the rectangular shape of the frame to clarify and intensify the actions within in it. Here, the director uses the frame to create meaningful, arranged compositions within the two-dimensional screen space, allowing us to more easily experience things like triangular compositions where character positions form triangular shapes, often to reinforce underlying thematic concerns. In the famous scene from Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941) the young Charles Foster Kane, powerless to determine his future and soon to be sent away from his mother, is centered at the bottom of a triangular composition that features –as an inside joke perhaps – an actual triangle dinner bell placed deep in the center of the space (Figure 1.1). In such moments, the audience feels the formalizing approach of the director’s hand, carefully composing the scene to create meaning in purely visual terms.

Figure 1.1 The formalizing function of the frame in Citizen Kane. In this shot from Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941) the film frame functions more like the frame of a classical painting, creating clear diagonal and triangular patterns that reinforce underlying thematic concerns: here, the young Charlie Kane is at the center of a custody squabble over whether he will remain with his mother on the right and his father center, or be taken to the city to be raised by Mr. Thatcher on the left.

Source: Copyright 1941 RKO Radio Pictures.

In the second case – frame as window – the director selects an area of the world without tightly controlling what happens within the screen space, so that the action spills off screen, a style of direction that remains true to the realistic décor before the camera, minimizing the difference between the audience’s perception of the screen and normal perception, and forcing the audience to seek out areas of visual interest without the guiding hand of the director. Ridley Scott exploits this notion of “frame as window” in many shots within the opening battle scene of Gladiator (Scott, 2000), coupling it with underexposure, to force the audience to explore the frame (Figure 1.2).

This early theorizing about screen space and the dual nature of the frame was broadened, and carried into the contemporary arena of practical theorizing by Dr. Herbert Zettl. Zettl is a Professor Emeritus of Broadcasting and Electronic Communication Arts in the College of Creative Arts at San Francisco State University. He studied at Stanford University in the 1950s where he received bachelors and masters degrees. Early influences included the philosophy of Bauhaus design and gestalt psychology. The seminal work by Rudolf Arnheim, Art and visual perception: a psychology of the creative eye (1954), greatly influenced Zettl, who published a dissertation on the use of television in adult education in 1966, earning his doctorate from University of California, Berkeley.

A teacher-scholar for 50 years, Zettl was a very early advocate for the notion that television could be an art form, a visionary idea when his book Sight, sound, motion was first published in 1973. This text, revised and developed in the eight editions that followed, theorizes how moving images can not only be “read” to understand their underlying creative structures – a process long known to traditional aesthetics – but how new moving images can be conceived and “written” to communicate with maximum effectiveness. Fundamental concepts Zettl articulated like vectors, principal, secondary and tertiary motions, event intensity, etc. gave producers and scholars alike a new descriptive vocabulary for unpacking the underlying aesthetic forces that shape moving images. An advocate for the notion that the museum is not the sole province of art, Zettl argues that life and art are dependent, that aesthetic experiences are part of everyday life, and that all experience has the potential to be the raw material for art if it is structured effectively.

Figure 1.2 Frame as window in Gladiator. In this shot from Gladiator (Scott, 2000), the film frame functions more like a window, creating the sense of a real battle as the clashing armies chaotically spill outside the frame. Here, the rectangular frame structures the visual field less formally, forcing the audience to scan the frame to discover areas of significance.

Source: Copyright 2000 Dreamworks Pictures.

Sight, sound, motion also offers an insightful, creative guide to applied media aesthetics, which in the case of television, film and other audiovisual media, is the examination of the formal elements of media (like sound, lighting, camera angle, etc.) to understand how they interact, and how the viewer reacts to them.7 Zettl argues that, like writing where we learn parts of speech and vocabulary as essential prerequisites for creative writing, we need to study the fundamental image elements that function within the “aesthetic field” that the filmmaker manipulates in creating a film.8 While traditional aesthetics can be used for critical analysis of a completed work, Zettl advocates applied media aesthetics because it can be practiced when we analyze existing media and when we synthesize or create media at the production stage. For the editor, the most important elements Zettl identifies that we need to learn to structure are the forces within the two-dimensional field (Figure 1.3), and the four-dimensional field of time/motion.

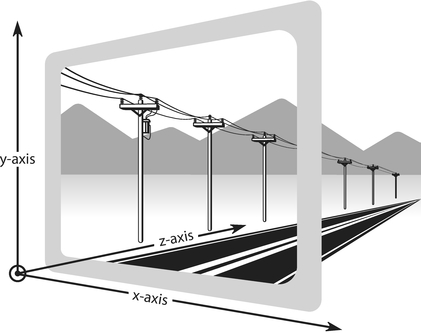

According to Zettl, the film frame gives us a field with three axes, following the Cartesian coordinate system of x-axis for the horizontal dimension, y-axis for the vertical dimension and z-axis for the line extending from the camera to the horizon. With this three-dimensional spatial framework established, Zettl can specify any number of dynamic forces within the frame space using the concept of a vector. Borrowing from the term in physics, Zettl says that “In media aesthetics [a vector is] a perceivable force with a direction and a magnitude.”9 He goes further to delineate three main types of vectors in film:

Figure 1.3 The x,y,z coordinate system applied to the film frame. The spatial coordinate system first developed by Rene Descartes in the seventeenth century has been usefully adapted by Herbert Zettl to describe the screen forces and primary motions that occur within a film frame.

Source: Illustration adapted from Zettl.

- 1) A graphic vector is one created by a line or screen elements arranged to suggest a line. Graphic vectors do not indicate a clear-cut direction, but they do have a prevailing tendency: they may be predominantly horizontal, vertical, rounded, elliptical, etc. So we recognize, for example, a horizontal graphic vector in the shot of a building (Figure 1.4) as positioned along the x-axis without knowing if it suggests a direction left or right. Here, the horizontal vector can be scanned by the audience either left to right – an easier process for cultures who read left to right – or right to left, with a bit more effort.

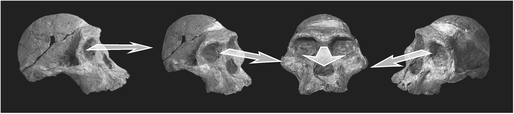

- 2) An index vector is one created by something that clearly points in a specific direction. The human face, a loud speaker, a pistol, a lens, an automobile – anything that points in a single direction – carries that directionality into the frame and creates an index vector (Figures 1.5 and 1.6).

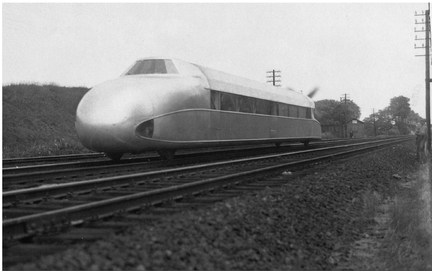

- 3) A motion vector is one created by something moving across the frame in a particular direction.10 A film of a train in motion (shown here as a still photograph) is an example of a motion vector. Using Zettl’s x, y, z coordinate system, we could describe the image more precisely as exhibiting a predominantly z-axis motion vector that moves principally right to left, along the shallow z-axis angle created by camera placement that allows the track to recede to the horizon mid-height at the right side of the frame (Figure 1.7).

Zettl develops the notion of vector further, pointing out that within each category of vector, there exist low magnitude and high magnitude instances. For example, one shot of the bridge can create a low magnitude and another a high magnitude graphic vector (Figures 1.8 and 1.9).

Similarly, motion vectors created by objects moving quickly across the frame are higher in magnitude than those created by slower moving objects.

We can also compare relative magnitude across categories: other things being equal, motion vectors are inherently higher in magnitude than index vectors, which are higher in magnitude than graphic vectors. In other words, elements that simply create line within the screen space will always be relatively less impactful, less dynamic than an index vector that has an unambiguous front/back orientation, or motion vectors that transit the screen space, entering, exiting, crossing horizontally or moving dynamically towards the camera. To summarize, while each category may exhibit low and high magnitude instances, when we compare vector magnitude:

motion vectors > index vectors > graphic vectors.

As editors, when we apply this scheme of screen vectors to existing films or to source footage, we begin to understand that the vector field – the mix of vectors exhibited by a moving image –can be enormously complex, and may vary based on the unit of analysis chosen. Are we analyzing

Figure 1.4 Horizontal graphic vector. This shot of the library at Immaculata University exhibits a predominantly horizontal graphic vector, that is stable and balanced, punctuated by a few vertical elements.

Source: Ruhrfisch / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA.

Figure 1.5 Index vector of a fire hydrant. A shot of a fire hydrant contains an index vector, a perceivable screen force in a particular direction.

Source: Dori / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

Figure 1.6 Index vectors: skull. This composite shot of a 2.1 million-year-old specimen Australopithecus africanus discovered in South Africa exhibits a range of index vectors.

Source: José Braga; Didier Descouens / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0. Arrows added.

Figure 1.7 Oblique z-axis “motion” vector. If this were a moving shot, the train pictured above would create a motion vector on an oblique z-axis moving left to right.

Source: Franz Jansen (†), Erkrath / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0.

a screen vector field within a single frame? Are we analyzing a screen vector field as it changes frame to frame? Are we analyzing a vector field within a single shot? Are we analyzing a vector field within a sequence?

Along with questions about the unit of analysis, discussions of screen space require us to verbalize impressions of very complex visual phenomena. The spatial and temporal complexities created within the film frame by a series of shot changes is easy for us to read visually, but often overwhelming when we try to reduce it to simple, descriptive terms. In the case of screen vectors, we tend to simplify descriptions of the vector field – the myriad vectors that may manifest in a shot – into a single, short hand description of the dominant vector within a shot.

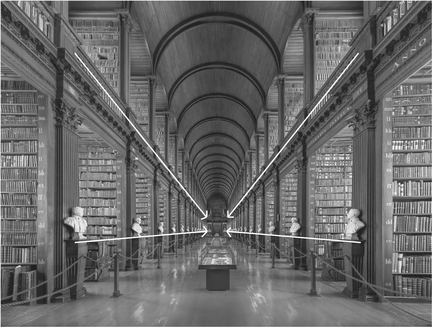

For example, there are many vertical and horizontal graphic elements in the shot of Old Library at Trinity College (Figure 1.10): the horizontal rows of books, the vertical pillars, the vertical stanchions holding the ropes and the vertical pedestals for the busts. But given the placement of the camera, the prominent central arch and upper railing, the dominant vector is the z-axis towards the center of the frame. We often simplify our description to “This image is a z-axis vector,” What we mean is that the dominant elements of the graphic vector field within a scene create a z-axis. So, at the level of a single frame, the vector field may contain a complex combination of one type of vector. Or, more likely, it will move beyond a single type of vector: the frame may simultaneously exhibit vertical graphic vectors and index vectors pointing in multiple z-axis directions. Moreover, if the unit of analysis moves from a single frame to a multiframe comparison, another type of vector is introduced: the motion vector of the main character may move left to right in the frame along the x-axis.

Figure 1.8 Low magnitude graphic vector: Brooklyn Bridge. Within each category of vector, there can be low magnitude . . .

Source: RMajouii / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 1.0.

Figure 1.9 High magnitude graphic vector: Brooklyn Bridge. . . .and high magnitude instances.

Source: Copyright (c) Postdif. via GNU Free Documentation License.

Here we begin to run into issues of complexity that can make analyzing vector fields across types of vectors and across a series of shots seem useless. Perhaps the most useful unit of analysis for the editor to return to ultimately is the last frame of the outgoing shot compared to the first frame of the incoming shot:11 specifically, what happens when the vector field of the outgoing shot changes to the vector field of the incoming shot? Does the general pattern of vectors continue in the incoming shot or is it discontinuous? When we edit for continuity, we try to maintain vectors that continue from shot to shot. In narrative filmmaking and in any film where we intend to keep the audience oriented spatially, Zettl argues that we need to follow a prescribed syntax of continuity editing, a classical pattern of select ing and sequencing images that maintains the spectator’s spatial orientation, allowing them to easily maintain a cognitive mental map that structures and unifies their reading of the on and off screen space given by the shots in a sequence.12 In the discussion that follows, the underlying assumption is that an editor would follow this syntax of continuity editing almost by default, as it is the general practice when we distill narrative events to tell stories, or more generally in any moving image text when we want to create a consistent, orderly spatial progression. Discontinuous approaches are more likely used for other purposes, including purely abstract visual sequences, and for instances of complexity editing, the use of shots – independent of whether or not they follow the conventions of continuity editing – to reveal the story and amplify the underlying emotion of a scene. 13

Graphic Vectors and Index Vectors: Continuity and Discontinuity

Figure 1.10 Dominant z-axis vector. The vector field in this shot contains vertical and horizontal elements, but given the placement of the camera, the prominent central arch and upper railing, the dominant vector is the z-axis towards the center of the frame. A shorthand description of the image would be, “This image is a z-axis vector,” meaning the dominant elements of the graphic vector field within a scene create a z-axis.

Source: David Iliff / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 3.0.

Consider the case of shots that do not contain motion, but do contain screen elements arranged in a line, like a shot of the open desert road extending to the horizon (Figure 1.11). This is a graphic vector with a prevailing z-axis orientation, but one that does not indicate a clear-cut direction, since it can be seen either as extending away from the camera or towards the camera. If the editor cuts from that image to another image of an open desert road extending to the horizon (Figure 1.12), the dominant z-axis graphic vector continues from outgoing to incoming shot.

As these images demonstrate, the more closely that vectors align from image to image, the smoother the cut.14 However, if we cut from the same outgoing shot (Figure 1.13) to a roadside sign in the desert landscape, the dominant z-axis graphic vector in the outgoing shot is replaced by the dominant horizontal, x-axis vector of the incoming shot (Figure 1.14), made prominent by the sign, the road and the mountains in the distance. Since the graphic vector field changes, a cut from Figure 1.13 to 1.14 exhibits what we can call discontinuous graphic vectors, even though the subject matter – the desert landscape – continues.

This designation is not to value continuous vectors above discontinuous vectors, as if “discontinuous” was somehow less useful: determining how the vector field changes from shot to shot may be only one of many considerations the editor faces when considering a shot change. Beyond graphic vector continuity/discontinuity, Zettl articulates three other cases in the image track where editing is concerned with vector fields: index vector continuity/discontinuity, motion vector continuity/discontinuity and the special case of continuity using z-axis vectors.

Since an index vector usually points unambiguously in a specific direction, a cut from a shot containing one index vector to another index vector either continues the general directionality of the outgoing shot or does not continue it. If the dominant index vector continues, the change in screen space feels “softer,” the cut smoother, while large changes in the dominant index vector are considered “harder” cuts. For example, if the editor cuts from an outgoing shot of a ship with a specific index vector (Figure 1.15) to an incoming shot of another ship that roughly continues that same index vector (Figure 1.16), that is considered a relatively smooth cut.

Conversely, a cut with the incoming image of the ship’s prow flopped left to right would generally be regarded as a harder cut (Figure 1.18). Again, this is not a value judgment: a harder cut may be just what the editor is seeking.

Because the human face at rest looks in a specific direction, it has an inherent index vector. The face is the most prominent image in narrative films, and so the face is central to creating meaning in film through dialogue and facial expression. In the film world, this facial index vector is commonly called eye-line, the direction of a character’s look in the frame. Index vectors or eye-lines guide the viewer to see what the character sees within the frame – on screen space – as well as what the character sees outside the frame – off screen space. As the shots within a scene oscillate between objective and subjective camera, taking the character’s position in point-of-view placements, or simply cutting to what the character is looking at, index vectors of the principal actors’ faces are the primary cues to the spectator for spatial orientation. To paraphrase Stephen Heath, the spectator reads a film on the basis of the camera’s view and the editor’s construction of those views into a flow of images. In Heath’s view, a film character becomes a “figure of the look. . . a kind of perspective within the [film’s] perspective system, regulating the world, orientating space, providing directions . . . for the spectator.”15 In short, the eye-lines of the characters orient the audience spatially.

Like Heath, Zettl believes that index vectors of the human face are key to building and stabilizing the viewer’s mental map, the viewer’s spatial orientation. 16 The index vector field of a shot can encompass index vectors that continue – a vector points in a direction and another vector points in the same direction; converge – a vector points towards another vector; or diverge – a vector points away from another vector. See Critical Commons, “Maltese Falcon: opening scene.”17 For example, in the opening of Maltese Falcon (John Huston, 1941) Ruth Wonderly (Mary Astor) comes to the office of Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) ostensibly to seek his help finding her missing sister.18 Huston establishes the two sitting opposite each other at Spade’s desk (Figure 1.19), then cuts in closer to an over-the-shoulder

Figure 1.11 Continuing graphic vector outgoing shot . . . If we cut from 1.11 to 1.12, the dominant graphic vector of the road leading to the horizon in the outgoing shot . . .

Source: Copyright (c) Nepenthes. via GNU Free Documentation License.

Figure 1.12 Incoming shot. . . . generally continues in the incoming shot. Since the graphic vector matches, a cut from a to b is continuous and smooth.

Source: William Warby / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY 2.0.

Figure 1.13 Discontinuous graphic vector outgoing shot. . . If we cut from 1.13 to 1.14, the dominant z-axis graphic vector of the road leading to the horizon in the outgoing shot . . .

Source: Copyright (c) Nepenthes. via GNU Free Documentation License.

Figure 1.14 Incoming shot. ...collides with the horizontal x-axis graphic vector of the incoming shot.

Source: Roger469 / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

Figure 1.15 Continuing index vector outgoing shot. . . If we cut from 1.15 to 1.16, the dominant index vector – the direction of the ship’s prow of the outgoing shot . . .

Source: Christian Ferrer / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 1.16 Incoming shot. . . . continues in the incoming shot, creating what most editors would regard as a “softer” cut. The incoming shot maintains the overall “gestalt” of the outgoing shot: the shot change does not ask the viewer to reorient the overall visual structure in processing the incoming image.

Source: IDS photos / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.0.

shot of Wonderly (Figure 1.20), so that her index vector (eye-line) in the outgoing two-shot continues in the incoming close up.

As with any continuity cut from a wider shot to a closer one, this is traditionally called a cut in. Its spatial clarity derives in part from the fact that it carries information that is redundant from the establishing shot. Its dramatic value in this opening scene is to concentrate the narrative exposition, since Wonderly recounts what brought her to Spade’s office: she is searching for her sister who has disappeared.

Figure 1.17 Discontinuous index vector outgoing shot. . . If we cut from 1.17 to 1.18, the dominant index vector – the direction of the ship’s prow of the outgoing shot . . .

Source: IDS photos / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 1.18 Incoming shot.. . .does not continue in the incoming shot, creating what most editors would regard as a “harder” cut, in that the incoming shot changes the overall directionality of the outgoing shot.

Source: IDS photos / Wikimedia Commons / CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 1.19 Continuing index vectors in a dialogue scene from Maltese Falcon. The last frame of the outgoing shot 1. . . In a dialogue scene between two people, the index vectors of the faces orient the viewer by continuing across the cut from the outgoing shot two shot . . .

Figure 1.20 First frame of the incoming shot 2. . . to the incoming over-the-shoulder shot.

Figure 1.21 The shot 3 reverses the angle. Huston’s next cut is to an over-the-shoulder shot where the converging index vectors of their faces, and particularly, their converging eye-lines, make the edits as spatially coherent as possible.

Figure 1.22 Shot-reverse shot: outgoing. Huston cuts shots from either end of the axis created by their converging eye-lines (and body positions) in an alternating pattern between the speaker . . .

Huston’s next cut is to an over-the-shoulder shot of Spade (Figure 1.21) that roughly matches the scale and graphic balance of the previous shot. In both over-the-shoulder shots, the converging index vectors of their faces, and particularly, their converging eye-lines, make the edits as spatially coherent as possible. This pattern – cutting from Figure 1.20 to Figure 1.21 – can be classified as a shot-reverse shot: shots from either end of the axis created by their converging eye-lines and body positions are cut in an alternating pattern between the speaker and the person spoken to. More typically, the shot-reverse shot pattern moves into close ups, and the two adjacent spaces shown are “knit together” by the converging eye-lines. Here, as the story Wonderly tells of searching for her sister gets more convoluted (Figure 1.22), Huston’s reverse close up of Spade shows his skepticism as he lights a cigarette (Figure 1.23).

This cutting pattern, a cinematic figure of style using alternating, converging close ups is ubiquitous in dialogue scenes, and began to appear around 1910. Bordwell notes this mechanism was unique to cinema: “The shot/reverse-shot device deserves to be called a stylistic invention [of cinema]. It wasn’ determined by the technology of the cinema, and I can find no plausible parallels in other nineteenth-century media, such as comics strips, paintings, or lantern slides.” 19 But at the same time, the parallels to human communication are obvious. Since personal communication where the speakers are directly facing each other is a universal human behavior, “shot/reverse shot is instantly recognizable across cultures and time periods.”20 By contrast, staging characters facing away from each other produces diverging index vectors, an atypical arrangement for conversation that suggests an unusual interpersonal dynamic. In a richly comedic scene from The Shop Around the Corner (Ernst Lubitsch, 1940) Alfred Kralik (James Stewart) is relentless in his quest to gain the attention of Klara Novak (Margaret Sullavan). While Lubitsch stages much of the dialogue in the usual converging index vectors, as Karlik returns to sit behind Klara at a restaurant (Figure 1.24), their index vectors initially diverge – but only briefly – as Stewart playfully tries to keep their conversation from ending. See Critical Commons, “The Shop Around the Corner: Converging and Diverging Index Vectors.”21

Figure 1.23 Shot-reverse shot: incoming. . . and the person spoken to. This unique figure of cinematic style is called shot-reverse shot, and began to appear around 1910.

Source: Copyright 1941 Warner Brothers.

Figure 1.24 Diverging index vectors. Staging characters facing away from each other produces diverging index vectors. In The Shop Around the Corner (Lubitsch, 1940) the index vectors of Alfred Kralik (James Stewart) and Klara Novak (Margaret Sullavan) initially diverge – but only briefly – as he playfully tries to keep their conversation going.

Source: Copyright 1940 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Clearly, staging dialogue with diverging index vectors can also suggest hostility or alienation between characters.

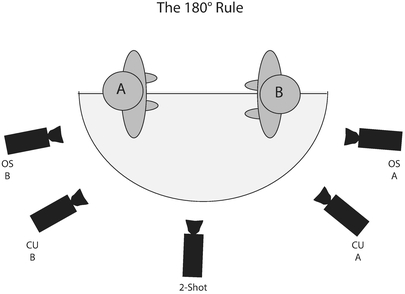

180° Rule: Continuity at the Production Stage

Once early films moved beyond full figure framing and tableaux staging, analytical editing became the dominant mode of the classical continuity style, and was firmly established around the world before 1920. Analytical editing is a style of cutting that first shows the scenic space in a wide, establishing shot to illustrate the relative positions of significant elements, and subsequently breaks down the action into closer shots, ensuring that the viewer is spatially oriented. Often, if a character changes position or crosses the space, a wide shot re-establishes the relative positions of the characters. (Herbert Zettl calls this the deductive approach; see p. 35 below.) At the production stage, the analytical style of editing was facilitated greatly by establishing an axis of action, an imaginary line between two characters facing each other, and always positioning the camera on one side of this line so that their eye-lines would converge in every shot. As Kristin Thompson has pointed out, the shooting environment in early studios often dictated this approach:

The introduction of the cut-in as a standard device and the resulting breakdown of a single scene into multiple shots brings up the question of screen direction (later to be called the “axis of action” or “180° rule”) . . . There was seldom any question of moving to the other side of the action. The standard painted sets had only a backdrop and perhaps two small segments of other walls at the sides. In order to keep the setting in the background of the closer shot, the camera had to stay on the same side of the characters. Since filmmakers usually did close-ups directly after the long shots, by simply carrying their cameras forward, problems seldom arose, even in exteriors done without sets.22

Figure 1.25 The 180° rule. Early in film history, directors realized that spatial coherence was easier to maintain at the editing stage if a primary axis of action was established and all of the shots for that scene are taken on the same side of that line. Using the master scene technique for a dialogue scene, five shots could typically provide safe coverage of a scene.

At the production stage, the mode of shooting to ensure that footage could be successfully cut in the analytical style became known as the 180° rule: in every scene where multiple shots of varying scope would be taken, a primary axis of action was established – an imaginary line created by converging index vectors of two people talking, or the motion vector of a ship moving across the water – and all of the shots for that scene are taken on the same side of that line (i.e., within the semicircle that inscribes 180° on one side of that axis.)

Directors quickly learned that the safest way to ensure that a scene would cut together was to establish an axis of action in a scene, and then shoot it using the master scene (or master shot) technique, which captures a piece of dramatic action in long shot then repeats all or part of the action in closer shots. The 180° rule coupled with the master scene approach virtually guarantees that the takes will match in screen directionality, an idea echoed by Hollywood director Ron Howard, who tells beginning directors, “If all else fails, shoot a master and shoot overs [over-the shoulder shots] and singles.”23 For example, if two actors have a dialogue scene (Figure 1.25), five “standard” shots of the action could be taken in which all (or part of) the scene was photographed:

- a two-shot (master shot) in a wide shot showing the two characters (often the entire scene)

- over-the-shoulder shot of character A (repeat all or part of the action)

- close up of character A (repeat all or part of the action)

- over-the-shoulder shot of character B (repeat all or part of the action)

- close up of character B (repeat all or part of the action).

If all of these shots are taken from the same side of the axis of action, the index vectors of the character’s faces will match from shot to shot. The worldwide acceptance of this approach is noted by David Bordwell,

Commercial storytelling cinema has long followed the conventions of analytical editing: master shot, followed by a two-shot or over-the-shoulder shots, followed by singles highlighting each participant in shot/reverse–shot fashion. In fact, seldom do we find in any art a style with such pervasive presence and 100-year longevity. These norms have provided easy, comprehensible ways for narrative action to be understood.24

Bordwell points out that increasing the pace of dialogue scenes in more recent films

has reinforced certain premises of the 180-degree staging system. When every shot is short, when establishing shots are brief or postponed or nonexistent, the eyelines and angles in a dialogue need to be even more unambiguous, and the axis of action is likely to be respected quite strictly. . . Still, the 1990s saw a slight tendency for the camera’s viewpoint to hop back and forth across the 180-degree line during dialogue scenes.25

Of course, crossing the 180° line makes the index vectors of the characters’ bodies and faces flip back and forth from shot to shot, and while establishing an axis was one of the few hard and fast rules of the studio system, many violations – intentional or otherwise – are scattered throughout film history. A few examples will suffice.

In The Getaway (Sam Peckinpah, 1972) an ex-con Carter “Doc” McCoy (Steve McQueen) and Carol McCoy (Ali MacGraw) launch a tenuous romantic relationship as they run from the law after a botched robbery. When they reunite at a train station, Carol asserts the power of her sexuality, acknowledging what Doc is angry about: that she did sleep with a man to obtain his release from prison, and that she can get him out of prison at any time because she can “screw every prison official in Texas if I want to.” The tension between love and sexuality is underlined when Peckinpah crosses the 180° line, reversing their position in the frame, as Carol asks “You’d do the same for me, Doc, wouldn’t you? I mean, if I got caught, wouldn’t you?” Here, the visual swapping of their positions highlights the sacrifice Carol has made and punctuates her demand for equality in their budding relationship. See Critical Commons, “A violation of the 180-degree rule.”26 A more prominent use of this “visual swapping” happens in the famous bathroom scene from The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980). Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) the newly-hired, mentally unstable caretaker of the Overlook Hotel confronts the ghost of Delbert Grady (Philip Stone) in the bathroom of the hotel bar, where Jack goes to clean up after he has spilled a drink on himself. See Critical Commons, “The Shining: Crossing the 180° Line.”27 Jack says he recognizes Mr. Grady from the newspapers as the former caretaker who chopped his wife and daughters to bits, and then blew his brains out. The film cuts very slowly back and forth across the axis of action as Grady first answers that he has no recollection of that (Figure 1.26), and then that Jack is the caretaker, and has always been the caretaker (Figure 1.27). Part of the impact that Kubrick derives from cutting across the 180° line in this scene comes from the highly symmetrical composition of every shot, using single point perspective where the orthogonal of both ceiling and floor converge on the two centered characters, framed in either a plan américain or wide shot taken with a short lens, before the scene ever cuts to a single.

The symmetrical, “visual swaps” collide as Kubrick cuts across the line, creating a visual metaphor linking Jack and Mr. Grady as unstable, socially isolated characters who are mysteriously drawn to the caretaker position at the Overlook Hotel.

Figure 1.26 Crossing the 180° line, outgoing shot . . . In The Shining, Kubrick cuts across the 180° line to create a visual metaphor linking Jack (Jack Nicholson) and Mr. Grady (Philip Stone) as socially isolated characters by flipping their position from shot . . .

Figure 1.27 Incoming shot . . . to shot.

Source: Copyright 1980 Warner Brothers.

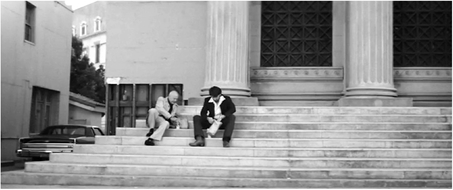

In the more recent Argo (Ben Affleck, 2012) a dialogue scene early in the film demonstrates a contemporary approach to shooting dialogue, a style that reflects a much looser adherence to the pervasive Hollywood norms attached to the 180° rule. The scene shows two men driving to get lunch, and sitting down to eat it: Tony Mendez (Ben Affleck), a CIA expert in exfiltration, and Lester Siegel (Alan Arkin), a Hollywood producer he hopes to work with to free the six American embassy officials who were captured when Iranian students stormed the U.S. Embassy in Teheran and took 60 people hostage in 1979. The establishing shot of their meal is a long shot of the granite steps as they open the bags of food (Figure 1.28), a shot the film does not return to. The traditional axis of action would be the line between them, and the 180° of space in front of them would inscribe the traditional arc where single shots of the actors are taken as three-quarter frontal close ups. Instead, the second shot is a “reverse” over-the-shoulder shot taken from “across the axis,” from behind them that shows a profile of Affleck (Figure 1.29) and the back of Arkin’s head. As they talk about their families, the shots continue in this fashion: shot-reverse shot using over-the-shoulder shots from behind them, where one subject’s shoulder is in the shot and the other character is in profile (Figure 1.30). The fourth shot of the sequence is a tight two-shot that re-establishes the space of their conversation from behind (Figure 1.31), and in a sense confirms that the 180° space behind them will remain the axis of action for the scene. See Critical Commons, “Argo: Continuing Motion Vector and Crossing the 180° Line.”28 Some of these staging choices may have been driven by the fact that camera placement would be easier behind them, and also that by shooting from behind them, the sequence creates a feeling for the space of the studio lot that they look out on to. This staging of the seated dialogue scene, shot from behind in over-the-shoulder shots or singles, has become a common and effective re-imagination of the more rigid approach dictated by strict adherence to 180° staging.

Figure 1.28 Establishing shot from Argo. In Argo, the establishing shot of Tony Mendez (Ben Affleck) and Lester Siegel (Alan Arkin) having lunch on a studio lot suggests a traditional line of action. . .

Figure 1.29 Over-the-shoulder shot from “across the axis”.. . that is immediately crossed by a “reverse” over-the-shoulder shot.

Figure 1.30 Over-the-shoulder shot from “across the axis”. The pattern of over-the-shoulder shots taken from “across the axis” continues . . .

Figure 1.31 Two-shot “re-establishes”.. . when a cut to a tight two-shot “re-establishes” the axis of action behind them, an effective re-imagination of the more rigid approach dictated by strict adherence to 180° staging.

Source: Copyright 2012 Warner Brothers.

Motion Vectors: Continuing, Converging

Like index vectors, objects in motion within the frame create a dominant vector of movement. And as with index vectors, an editor can look at a shot change to see how the motion vector of the outgoing shot relates to the motion vector of the incoming shot. As a shot changes, the dominant motion vector of the incoming shot can continue the motion vector of the outgoing shot, converge with the motion vector of the outgoing shot or diverge from the motion vector of the outgoing shot.

In Argo, a typical, “garden variety” motion vector that continues over the cut is found in the scene we just examined. As Tony Mendez drives off the studio lot seated in Lester Siegel’s golden Rolls Royce, Affleck cuts in closer, maintaining the motion vector across the cut, showing the two proceeding with their plan for developing the fake movie that will be their cover story. While the outgoing shot establishes the Burbank studio, the gate and the car (Figure 1.32), the closer incoming shot confirms the characters within (Figure 1.33). And given the high magnitude of the motion vector the first shot establishes, continuing that in the second – matching direction and speed – is crucial for maintaining the viewer’s orientation across the edit.

Figure 1.32 Continuing motion vector outgoing shot. . . The high magnitude of the motion vector from the outgoing shot . . .

Figure 1.33 Incoming shot.. . continues in the incoming – matching direction and speed – and confirming the characters within.

Source: Copyright 2012 Warner Brothers.

Like the shot-reverse shot that utilizes converging index vectors, converging motion vectors is a powerful method for knitting together cinematic space. A typical trope that uses converging motion vectors is the “romantic run” that intercuts shots of lovers running towards each other. In Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939), Melanie Hamilton (Olivia de Havilland) sees a returning soldier in the distance coming towards Tara plantation, and assuming he is hungry like the others who have happened by, starts to go inside to prepare some food for him. She slowly realizes it is her husband Ashley Wilkes (Leslie Howard), and begins to run towards him. After two wide shots – one that establishes Melanie coming off the porch of Tara and a second that establishes them both accelerating on the same path towards each other – dynamic, converging motion vectors are created with studio tracking shots set against rear screen projections, first of Melanie moving right to left (Figure 1.34), then Ashley left to right (Figure 1.35). See Critical Commons, “Gone with the Wind: Converging Motion Vectors.”29

Unlike a “last minutes rescue” where the converging shots would accelerate to build excitement, here the tracking shots alternate but do not accelerate: Melanie (:01 second, 14 frames), Ashley (:02 seconds, 6 frames), Melanie (:02 seconds, 6 frames). The sequence resolves with Ashley stepping

Figure 1.34 Converging motion vector outgoing shot. . . Converging motion vectors are created with studio tracking shots set against rear screen projections, first of Melanie Hamilton (Olivia de Havilland) running to meet . . .

Figure 1.35 Incoming shot. . . her husband Ashley Wilkes (Leslie Howard) returning from the war.

Source: Copyright 1939 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

into a wide shot, staged in a 3/4 profile, that Melanie enters to embrace him (:07 seconds, 10 frames). As she does, the camera dollies in closer signaling the resolution of their reunion.

Figure 1.36 Converging motion vector outgoing shot. . . Using a widescreen format, Wes Anderson frames wide shots with strict rectilinear staging that tracks and slowly converges right to left motion. . .

Figure 1.37 Incoming shot. . . with left to right motion.

Source: Copyright 2012 Focus Features.

Another quirky version of this figure of style, the “romantic convergence,” is found in Moonrise Kingdom (Wes Anderson, 2012) where Sam (Jared Gilman) and Suzy (Kara Hayward) decide to elope, and meet in a field to plot their escape. See Critical Commons, “Moonrise Kingdom: Converging Motion Vectors.”30 There’s no running here, just two twelve-year-olds hauling maps, canteens, binoculars, beef jerky and a trout fishing creel with a cat inside. Using a widescreen format, Anderson also frames wider shots with strict, self-conscious, rectilinear staging: balanced waist shots with converging index vectors and extensive “look space” give way to formal, full shots with slower tracking that only advance once the character moves (Figures 1.36 and 1.37). The pattern is the same as Gone with the Wind, but slower: Sam (:04 seconds, 3 frames), Suzy (:03 seconds, 18 frames), Sam (:04 seconds, 17 frames), resolving in Suzy’s final tracking shot where they converse at length, and then exit (:21 seconds, 15 frames). As Bordwell notes, formal, planimetric staging and deliberate, rectilinear camera moves “opens up the comic possibilities that Keaton recognized in such films as Neighbors and The General. A rigid perpendicular angle can endow action with an absurd geometry and a deadpan humor, qualities that Anderson has exploited freely.”31

A Special Case: Continuity with Z-axis Index Vectors and Z-axis Motion Vectors

Converging vectors move dynamically across the x-axis primarily, but images with strong z-axis orientation – potentially the most neutral orientation – offer the editor a special opportunity to cut with limited juxtaposition to the vector field of the shot that comes before or after it. Zettl argues that a typical image showing a dominant z-axis vector has zero directionality because it does not point to a screen edge and the off screen space beyond that edge, but rather straight ahead at the space “behind the camera.”32 So in a sequence with strong z-axis staging, spatial orientation for the viewer is not as pressing an issue. Typical examples would be a head-on close up of a human subject (a neutral, z-axis index vector), or a head-on shot of a vehicle moving towards or away from the camera (a neutral, z-axis motion vector).

In the opening of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (John Hughes, 1986), Ferris (Matthew Broderick) breaks the fourth wall by telling the audience how he plans to skip school. In a variety of shots, Ferris delivers his lines directly to camera – a neutral, z-axis index vector that dominates the composition. See Critical Commons, “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off: Z-axis staging for ‘zero directionality.’”33 Each cut that follows these neutral shots moves the story forward spatially and temporally, and the cuts are smoothed by the zero directionality of staging his lines into the camera. Notice that each shot following a z-axis shot begins with an “empty frame”: Ferris is not present in the incoming frame (or he is just entering the incoming frame), so matching the action of his body from shot-to-shot is not the issue (see further uses of the word “match” in Chapter 3, p.87).

The sequence opens with a few cuts that are on the z-axis, but not directly into the camera. Standing at a window, Ferris addresses the viewer directly and asks, “How could I possibly be expected to handle school on a day like this?” Then he looks up, into the distant sky above the camera, and a series of five quick cuts of the sky follow, shots from his point of view. This figure of style is often called a referential cut: a character looks towards a space outside the space of the frame, the shot holds for a few frames, then cuts to what the character is looking at. Later, Ferris is in the shower, complaining about a test he has that day on European socialism, staged in a medium close-up addressing the camera, creating a zero directionality vector field (Figure 1.38). Herbert Zettl argues that the neutrality of the outgoing shot “softens” the incoming shot, a closeup of a shower head pointing right to left that carries a high magnitude, x-axis index vector (Figure 1.39). Zero directionality throughout the monologue scene simplifies many of the issues of cutting to shots carrying vectors of higher magnitude.

Consider a romantic scene between two lovers. A classically edited scene might include the typical moment where the lovers gaze into each other’s eyes, directly addressing the camera and locating the viewer as the subject of the lovers’ gazes. Typically, z-axis close-ups read as continuing the converging index vectors of the two-shot. An awkward romantic kiss that plays on these classical conventions is found in Moonrise Kingdom. See Critical Commons, “Moonrise Kingdom: Converging Vectors, Crossing the 180° Line, Z-axis Vectors.”34 Sam and Suzy celebrate their freedom on the beach by playing records and dancing. The line of action established by shooting from the shoreline towards the lake creates converging index and motion vectors as they dance wildly, then move to embrace and dance closer, leading to a first kiss, and a first French kiss. Anderson crosses the line of action for a tight over-the-shoulder shot as Suzy pulls Sam close, the camera moves back and forth across the line as they trade lines about Sam’s awkward erection. The line crossing is temporarily “neutralized” by two tight, z-axis close ups.

Figure 1.38 Cutting from a “zero-directionality” z-axis outgoing shot . . . Ferris Bueller is in the shower addressing the camera, creating a z-axis, “zero directionality” vector field. Herbert Zettl argues that the neutrality of the outgoing shot . . .

Figure 1.39 to a x-axis incoming shot.. . .“softens” the cut to the incoming shot, a close up of a shower head with a strong x-axis index vector.

Source: Copyright 1986 Paramount.

In a play on the romantic gaze directly into camera, Sam asks Suzy to tilt her head before he kisses her (Figure 1.40), and in the next shot she complies (Figure 1.41). These z-axis shots easily read as continuing the converging index vectors of the outgoing over-the-shoulder shot of Suzy that came before (not pictured). Moreover, with zero directionality these two close ups cut smoothly with the next shot from “across the line” (i.e., from the lake towards shore) of their feet stepping closer together (Figure 1.42). Here again, Zettl’s claim that the neutrality of the outgoing screen vectors eases the cut to the higher magnitude x-axis shot of the feet seems correct. The scene closes with a two-shot of Sam touching Suzy’s breast –Suzy: “I think they’re going to grow more” – and a neutral cutaway to the portable record player that plays out the scene.

Figure 1.40 Cutting from a “zero-directionality” z-axis outgoing shot . . . Moonrise Kingdom: two tight z-axis close ups of Sam . . .

Figure 1.41 to a second z-axis shot. . . and Suzy signal their upcoming kiss. With “zero directionality” these two close ups cut smoothly . . .

Figure 1.42 to a shot with converging x-axis vectors. . . .with the next x-axis shot of their feet stepping closer together.

Source: Copyright 2012 Focus Features.

Again, z-axis shots – because of their neutrality, their zero directionality – are useful in other settings including, for example, chase sequences. See Critical Commons, “Lucy: Neutral Z-axis Vectors Cut Easily as Continuing.”35 In Lucy (Luc Besson, 2014), the protagonist Lucy (Scarlett Johansson) is a woman endowed with psychokinetic abilities after she unwillingly absorbs a powerful drug. Lucy, who has never driven a car before, commandeers the police car of Pierre Del Rio (Amr Waked) and races through the streets of Paris trying to rescue a person at the hospital. The police car leaves the street and drives onto the covered sidewalk. At the beginning of this sequence, a series of three travelling shots races along with the car from behind (Figure 1.43). Two of these travelling shots are from “eye-level” and one is from a higher angle. Intercut with these z-axis travelling shots is a series of shots – two-shots and singles of Lucy and the policeman from inside the car (high magnitude x-axis vector field shot), and tracking shots of the car taken from the street towards the covered walk (high magnitude x-axis tracking shots). Because the z-axis travelling shots are zero magnitude, when intercut with Lucy driving (Figure 1.44) – a high magnitude “right to left vector field” – or with the tracking shot – a high magnitude “left to right vector field” – the cuts easily read as continuing motion vectors, facilitating smooth cutting within the chase.

Figure 1.43 Cutting from a “zero-directionality” z-axis outgoing shot . . . A shot that follows the police car in Lucy is zero magnitude allowing it to be easily cut with . . .

Figure 1.44 to an incoming shot with a high magnitude x-axis vector field. Lucy (Scarlett Johansson) driving – a high magnitude “right to left vector field.”

Source: Copyright 2014 Universal Pictures.

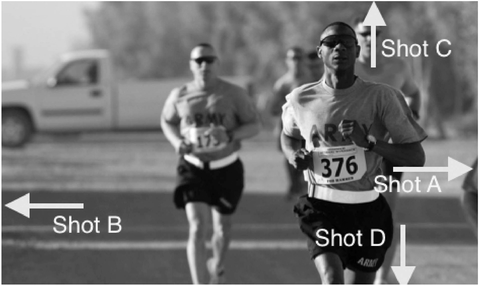

This method is typical for the chase sequence, where a neutral direction z-axis motion shot is used to ease the transition to a series of x-axis shots where the movements are right to left or left to right. Moreover, inserting a shot that initially has zero directionality but ends with a specific vector directionality can facilitate shifts in direction when cutting to shots that would otherwise reverse direction. In other words, if there are two shots – one left to right and one right to left – inserting a z-axis shot between them that transitions to a “right to left” motion solves the problem of reversing screen direction: it allows the editor to follow the directionality of the inserted cut. Theoretically, when shooting coverage for a chase scene, for example, it would be useful to gather z-axis shots towards the camera that cover all the potential screen directional changes (Figure 1.45), by having the character exit every off screen vector – essentially every frame edge – that the camera offers:

- Shot A: the character runs towards the camera and exits frame right.

- Shot B: the character runs towards the camera and exits frame left.

- Shot C: the character runs towards the camera leaping over a low camera placement.

- Shot D: the character runs towards the camera underneath a high camera placement.36

Figure 1.45 Four lines of movement from a z-axis shot.

Armed with this series of shots, an editor can use the z-axis neutrality to cover changes in the screen direction of subsequent shots, though in practice, A and B would be the most likely shots. Notice that the first two Shots A and B, while neutral at the beginning, offer the editor an opportunity to shift or pivot the directionality of the continuing motion vectors of a sequence: as the character exits, a non-neutral motion vector is created. A scene being assembled with a series of shots containing x-axis movements from right to left, and ending with a series of shots containing x-axis movements from left to right, can use Shot A above to soften the directionality shift and keep the audience oriented in space. In essence, using Shot A allows us cut to a neutral z-axis shot to “pause” the right to left series and then continue the directionality that Shot A ends with – a slight x-axis exit towards frame right – in the left to right shots that end the sequence. Shots C and D are even more neutral because they don’t end with an x-axis motion, but a y-axis exit either out of the top or bottom of the frame. These shots can also ease the transition to a different screen direction because they read as an even more neutral vector than Shots A (exit right) and B (exit left). In practice, they would more likely be cut with shots of the character moving away from camera on the z-axis, as in the editorial figure of speech called head-on, tail-away, where a character moves towards the camera until they fill the frame and the image goes soft then cuts to the same character moving away from the camera, to reveal what is “behind the camera” or to change to a new scene. For example, in Scarface (Brian De Palma, 1983) a musical montage depicts Tony Montana’s (Al Pacino) rise to incredible wealth. One cut shows Tony and his gang walking straight into the camera so that the frame is almost filled with his double-breasted coat and the lens begins to go dark. A soft-edged wipe to black crosses the frame from right to left, mimicking the shadow density of the outgoing shot, which is darkening from right to left as Tony almost touches the lens. The transition hangs in black for four frames, and then Tony moves away from the lens, in to the next scene (Tony is wearing a different coat) where the gang enters a newer, larger office for their expanding drug operations. Here the neutral z-axis motion directly into the camera provides a natural moment of soft focus, and a natural fade as the character approaches the camera and as he departs, allowing the creative match between the shots, and in this instance, creatively changing the scene to a different time and place. See Critical Commons, “Scarface: Z-axis Motion for a Head-on, Tail-away Edit.”37

Figure 1.46 Occurence at Owl Creek: Reverse dolly comes to a halt. As the camera reverse dollies with the condemned man staggering down a road, he stops and lifts his gaze upward, and then . . .

In Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge (Robert Enrico, 1962), a slightly different head-on, tail-away transition is used to advance the character “magically” forward as he approaches opening gates, a symbol of his return home and impending death. See Critical Commons, “Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge: Z-axis Staging for Head-on, Tail-away Edit.”38 Peyton Farquhar (Roger Jacquet) appears to escape his hanging on Owl Creek Bridge, and makes his way back through the woods to his homestead. As the the camera reverse dollies with Farquhar staggering down a road, he stops and lifts his gaze upwards (Figure 1.46). Pausing for a moment, a smile comes over his face and he proceeds forward until his shoulder almost covers the lens (Figure 1.47). This is a “head-on” movement that comes very close to the camera that is answered by a “tail-away” wide shot that marks a “magical” ellipsis (Figure 1.48): the man has advanced a few yards forward in the incoming, and is already stepping through gates that appear to have opened autonomously, magically granting his entrance. The use of neutral, z-axis staging in both shots facilitates spatial clarity and a smooth, elliptical cut through the gates that magically welcome him. This style of creative editing was part of the reason the French film won an award at Cannes and “Best Live Action Short Film” in the 1963 Academy Awards, before appearing on Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone in 1964.

Figure 1.47 A “head on” move to the camera in the outgoing shot . . . he proceeds forward until his shoulder almost covers the lens. This is a “head on” movement that comes very close to camera that is answered by...

Figure 1.48 cuts to the incoming shot. . . a “tail away” wide shot that marks a “magical” ellipsis: the man has advanced a few yards forward in the incoming shot.

Source: Copyright 1962 Film du Centaure.

Broader Views for Building Screen Space

Considering vectors that continue, converge and diverge is one of the fundamental approaches to thinking about how screen space is built. Considering how screen forces found in the outgoing shot relate to those found in the incoming shot can be a useful tool for evaluating what is happening across a specific cut. Taking a broader view, Zettl offers two more comprehensive schemas to understand the construction of a film or video: how it will be visualized – ways of looking – and how it will be structured – inductive versus deductive approaches. Zettl presents these ideas as questions for the director at the preproduction stage, and uses them to stimulate considerations about where the work will ultimately be presented, on anything from a small low definition display like a cell phone to a large movie screen. While these considerations are crucial for preproduction planning, they also offer the editor a practical tool to use when building screen space in postproduction. Clearly, an editor must take as a starting point the footage available. Yet, both of these approaches can be helpful as the editor assembles his or her drafts of the story, and works through the development of “what follows what” in building a sequence.

Ways of Looking: Looking at, Looking into, Creating an Event

Zettl argues that representing reality with moving images requires a basic decision in our visual approach when creating media. While noting that these approaches may overlap with one another, Zettl identifies the three approaches as follows:

Looking at an Event

If the event is to be presented on screen in order to clarify the viewer’s understanding of what is occurring, the camera’s view of the event follows closely the point of view of someone actually present and merely reports the main elements of the event as it unfolds. For a director at the production stage, and for the editor in postproduction, this approach would dictate the use of straightforward angles and naturally exposed images that are composed to allow the audience to clearly see the action at hand. In a staged dialogue scene between two people, shots that clearly establish the relative position of each speaker and straightforward images showing the speakers as alternates their dialogue back and forth would fit this style. In other words, event clarification guides the construction from shot to shot.39

Most television coverage of live sporting events – at least in their play by play presentation of the game – tend to merely look at the event, assuming an objective and neutral construction of the actions unfolding. In the realm of motion pictures, the observational documentary is considered a form that tries to objectively look at events unfolding before the camera. Known also as direct cinema or cinema vérité, in an observational documentary,

the focus of the film is usually on the details of everyday life, often in intimate settings. It can be thought of as the ‘fly on the wall’ type of approach. The final version of the film is not dominated by voice-over, and point of view is that of the characters in the film; there is no script. The viewer is looking in on and overhearing the people’s lived experiences.40

Utilizing the latest portable camera and sound equipment, Salesman (Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Charlotte Zwerin, 1968) looks at four salesmen as they travel in New England and Florida selling expensive Bibles door-to-door. The film’s opening scene shows Paul Brennan seated in a living room with a woman, making small talk and touting the features of the edition, as her child climbs all over and fiddles around on a nearby piano. The camera’s point of view places the viewer in the room, remains relatively objective throughout, showing the main events of their interaction. The event is delineated, not interpreted, with no significant attempt to highlight the psychological implications of the character’s interaction. See Critical Commons, “Salesman opening.”41

Looking into an Event

If an event is to be presented on screen in order to probe its psychological connotations, its underlying emotional tensions and unspoken implications, then its screen presentation must move beyond clarification and work to intensify the event. One of the primary tools used to intensify an event on screen is the use of closer shots of event details. Event “intensification” employs more overt stylistic elements that go beyond those found in classically edited Hollywood narratives to reveal unfolding character psychology.42 Here, in a staged dialogue scene like the one described above, a director might intensify the scene by including close shots of hand gestures, oblique angles of speakers and extreme close ups of eyes. If these moments are included in such a way that makes covering the dialogue almost a secondary concern, the audience begins to probe the subtext of the scene. Here, event intensification not event clarification guides the scene’s construction.

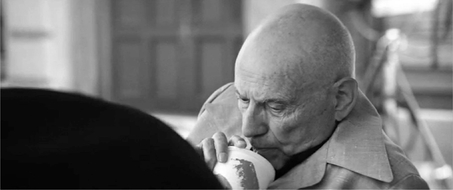

In The Passion of Joan of Arc (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1928), Joan of Arc (Renée Jeanne Falconetti) has fought the English, been captured and taken to Normandy to be tried for heresy by clerics loyal to the English. See Critical Commons, “The Passion of Joan of Arc: Looking into an Event.”43 Dreyer uses the iris as a framing device to enclose the tight close ups that are used almost exclusively throughout the scene. Alternating subjective, z-axis close ups from low and high angles, Dreyer skips the long shots that would clarify the spatial arrangement of the scene. When Joan says that “The English will be pushed out of France. . . ” Dreyer cuts energetically between pan shots and close ups of the interrogators, punctuating their troubled reactions. When she continues “ . . . except those who die here!” Dreyer goes so far as to stage a close up of an angry soldier on a swing, cutting so that his face pushes forward in a rage angrily towards the camera, not once, but twice (Figure 1.49).

Figure 1.49 The Passion of Joan of Arc: looking into an event. Dreyer stages a close up of an angry soldier on a swing, cutting so that his face pushes forward in a rage towards the camera twice.

Source: Copyright 1928 Société Générale des Films.

Next, a tracking shot increases the rhythm of the scene as the other clerics stir with agitation. Only towards the end of this sequence does a cleric dressed in dark robes rise and step into the same filmic space where Joan kneels, bringing accused and accuser together in the same space. By using close ups almost exclusively, Dreyer is able to show us to the burning eyes of a female zealot and the myriad facial types of powerful old men whose sneering looks and skeptical glances carry the emotional tension simmering within the scene. Examining this underlying tension is the thrust of Dreyer’s approach, a goal that moves beyond the simple clarification of plot events.

Creating an Event

If an event is captured with the aim of completely transforming it using the potentials of the medium, we create an event that is unique and exists only on the screen. When we create an event, postproduction processes are emphasized with the primary aim to form and shape the event using digital effects. The editor takes source footage and “turns up the art” to construct media-dependent images, visualizations that bear little resemblance to the real world. In narrative films, such visual effects might be used to represent anxiety, delirium or a psychotic state. In an abstract art film, these visual effects might be used to interrogate the formal potentials of the medium itself. In either case, event complexity, transforming the lens-captured event into one that is medium dependent and formally expressive guides the scene’s construction. (See also the discussion of creating a Lezginka event in Chapter 5, p. 173)

Figure 1.50 Persona: creating an event. Persona opens with a montage that is a reflexive meditation which is complex, signifying and a medium-dependent experience.

Source: Copyright 1966 AB Svensk Filmindustri.

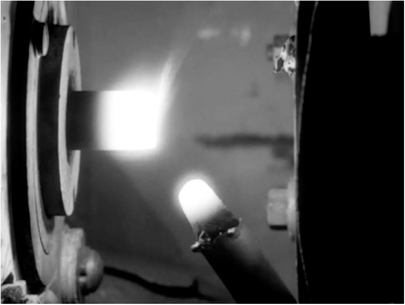

In Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966), the film opens with a montage that is a reflexive meditation on how film as a medium can address personal anguish and death, and how the spectator connects to the mediated world the film creates. See Critical Commons, “Persona: Creating an event.”44 Bergman opens with a shot of two carbon rods igniting in an arc lamp film projector (Figure 1.50), and proceeds to intercut other imagery showing the physicality of cinema: a whirring projector shutter, a piece of film spooling off a projector sprocket, the lens and the film plane of the projector showing a countdown leader moving through the gate. (As a joke Bergman even inserts a very brief shot of an erect penis in the montage that syncs with the two pop, a 1kHz tone that is one frame long and placed two seconds before the start of the program as part of the Academy leader system to ensure synchronization between sound and picture in film.) More film transport sprockets, the projector loop, as well as images from an early animated film follow. After a section of solid white, over-exposed film, the montage shows a trick film in miniature on the white field, before moving to more visceral images printed into the white frame: a close up of a tarantula then a series of shots of a sheep being slaughtered and eviscerated. The montage ends with close ups of a crucifixion: a hand twitches and bleeds as the hammer strikes the nail. Here, the aim is using the medium of film itself to completely transform the meaning of the captured images from their simple referents into a complex, signifying, medium-dependent experience, one that takes for its subject matter the nature of the medium itself. As Susan Sontag writes, “Persona is not just a representation of transactions between the two characters, Alma and Elizabeth, but a meditation on the film which is ‘about’ them. The most explicit vehicle for this meditation is the opening and closing sequence, in which Bergman tries to create that film as an object: a finite object, a made object, a fragile perishable object, and therefore existing in space as well as time.”45 With the growing accessibility of digital video effects, the arena for experimentation in image transformation has been greatly extended. Creating a compelling, mediated screen event – an event that exists solely through the exploration of the formal potentials of digital imagery – is becoming a practical editorial approach for expressing a character’s inner events or for transforming ordinary footage for purely experimental ends. Moreover, the three broad approaches Zettl identifies here for building screen space can guide the filmmaker in envisioning a sequence, providing a general direction for the creation, selection and manipulation of shots depending on what the aim of the scene is: presenting the event clearly, intensifying the event, or transforming the event into a complex mediated experience.

Inductive Versus Deductive Approaches to Building Screen Space

At the micro level, at the level of the shot, Zettl proposes that the vector field can be a useful analytical scheme for understanding the visual forces at play when building a sequence shot by shot by shot. At the macro level, Zettl also catalogs two more broad approaches to building screen space that sequences images based on scope of the shot, based on how framing structures the on screen and off screen space. Zettl notes that the question of building screen space comes into acute focus when we construct “openings,” when the filmmaker considers how to open a sequence, or how to open a film, and he identifies two approaches to the problem: deductive sequencing versus inductive sequencing. When an editor opens a scene with a long shot that establishes the locale, time of day, and relative positions of event details that closer shots will subsequently reveal, this approach is sequencing images deductively (also known as analytical editing). A typical opening sequence might proceed with a long shot of a forest, a medium shot of a tree branch swaying in the wind, a medium shot of a bird on the ground searching for food, followed by a close up of a bee buzzing around a flower. Deductive sequencing of images – where the spectator is given the establishing shot first – is the dominant Hollywood approach. This style of opening asks little of the viewer, since the sequence clearly communicates the broad space of the scene first, and reinforces that orientation shot by shot by shot. Scope of the shot is a central feature of this approach: the wide shot, held for enough screen time for the audience to scan the frame, allows a complete “mental map” of the space to register. As closer shots follow – shots that will almost always use continuing graphic, index or motion vector – spatial orientation is almost guaranteed.

In contrast, when an editor starts with the particulars of the scene using a series of close ups to show event details before showing a wider shot, this approach is sequencing images inductively (also know as constructive editing).46 A typical opening sequence might begin with a close up of a rusted shovel against a wall, followed by a close up of galvanized bucket lying on its side, followed by a close up of the flywheel on an aging pump before showing a wider shot of the interior of a dilapidated barn. The editor carefully selects event details that give the essence of the scene, impressions that the viewer will – consciously or unconsciously – begin to actively interrogate and, as the images unfold, construct into a larger meaning. Inductive sequencing is thought to more actively engage the viewer than deductive sequencing since, in the absence of the opening wide shot, the viewer will try to synthesize the wider space and the broader meaning that the close shots seem to point to.

Note that these two approaches can stand alone or be interwoven. The opening title sequence of Lawrence Kasdan’s The Big Chill (1983) uses an interesting mix of deductive and inductive approaches to image sequencing, in essence cutting back and forth between the two types of images as Marvin Gaye sings I Heard It Through the Grapevine in the film’s opening track and the film’s main titles are presented. See Critical Commons, “Deductive and Inductive Approaches to Image Sequencing in The Big Chill.”47