7 Dream and Ritual

Andrei Tarkovsky and Maya Deren

Andrei Tarkovsky and Maya Deren are two filmmakers from different eras who made significant contributions to the art of filmmaking, and who also wrote theoretical works about their film practice. Taking their own film work as a starting point, Tarkovsky and Deren theorize that one of the filmmaker’s primary functions is the control of time within the shot. Since every shot necessarily has a sense of time inherent within it, these filmmakers embrace the temporal command of the shot (and thus ultimately of the film) – what Tarkovsky called “time pressure” and what Deren described as “composition in time” – as a primary element of artistic control. In other words, these two filmmakers see the control of the internal rhythm of a film, the rhythm created within a shot by the movement of actors or objects or the camera itself as a significant area of creative control, rather than external rhythm, the rhythm created by editing and length of the shots. Since both artists are interested in the connection between film and inner mental states, perhaps it is no coincidence that their work foregrounds rhythm as a primary resource for building oneiric structures in film. The stream of spaces and the range of movement tempos constructed in the imaginary realm of dreams can be mimicked through careful control of movement within a shot. We will examine a key film from each artist, and locate that work within their theorizing to better understand the aesthetic choices needed to create a representation of “inner” reality, that is, a screen construction that is oneiric (literally, “relating to dreams”) and anti-realistic.

While both artists concentrate on internal rhythm, their overall approach to creating oneiric films is different. Tarkovsky tries to simply show life to the viewer by removing all expressive, poetic formalization from the image, since the film image observes the fact of life over time, organized in a pattern dictated by life itself and by its time laws.1 At first, this appears to be a contradiction: with his dedication to capturing concrete “facts” and their natural temporal flow, how can Tarkovsky create the inner reality of dreams? Thorsten Botz-Bornstein argues that, “Dreams are not produced by a process that attempts to stylize the reality of waking life into a reality of dreams but what really ‘makes’ the dream is the fact that reality and non-reality seem indistinguishable.”2 One of the primary characteristics of dreaming is that it is “experience unchained,” a flow of mental activity freed from any constraint as the controlling power of our will is released, and the mind is isolated from the outer world. In a dream state, the unity of our conscious life, its regularity and coherence is upended. Without the ability to reflect logically, elements in our dreams that are based in reality, and elements that are not based in reality, are equivalent. Our experience of each, no matter how strange or how ordinary, is the same. Film art in Tarkovsky’s view can only duplicate the dream through the raw power of the bare cinematic image. “Dream is the artistic phenomenon within which (as Tarkovsky says about Bresson) all expressiveness of the image has been eliminated and where only ‘life itself’ remains expressive.”3 For Tarkovsky, “life itself” will find expression in the film image as time pressure or internal rhythm.

By contrast, Maya Deren’s approach to film is poetic. In 1953, at a symposium on poetry and film, she described this mode as “a ‘vertical’ investigation of a situation, in that it probes the ramifications of the moment, and is concerned with its qualities and its depth, so that you have poetry concerned, in a sense, not with what is occurring but with what it feels like, for what it means.”4 While traditional drama is based on character centered causality, presenting well defined individuals struggling to attain specific goals, there are moments even in Shakespeare’s work – Hamlet, for example – of these vertical, poetic moments. Later in the same symposium, Deren points out that Hamlet’s soliloquy “To be or not to be,” stops the forward progression of the drama to explore his feelings on whether he would be better off dead. Deren’s vertical, poetic approach to filmmaking grew out of her graduate level study of poetry, and ultimately

Deren’s early interest in the use of ritual and myth in poetry became a guiding force in her creative work. The French symbolist school and T. S. Eliot were particular key influences. The symbolist effort to spiritualize language and Elliot’s mystical method, which transformed the architecture of modern poetry, influenced both the nature and form of her films . . . Because they embodied the element of a depersonalized individual within the dramatic whole, Deren later came to call the form of her films ritualistic. She vigorously endeavored to develop a new syntax or vocabulary of filmic images.5

In practical terms, this approach meant that choreographed movements before the camera are carefully controlled for pace and often repeated, character movement and the syntax of continuity editing are used to break free of the natural laws of movement we find in our waking life, and – perhaps most important – the reliance on filmmaking “tricks” in the style of the French film pioneer Georges Méliès try “to convince us that an alternative universe is ‘true.’ “Hence, for Deren, Méliès’s beloved camera “tricks” are not mere technological stunts but sacred devices for linking the “real” to the “unreal.”6 In short, Maya Deren’s creation of oneiric films is more overt than Andrei Tarkovsky’s, employing a more explicit use of formal, poetic devices to unlock inner reality. To paraphrase Thorsten Botz-Bornstein, in Deren’s films, we see dreams in the film; in Tarkovsky’s films, we cannot see dreams in the film because the film itself is a dream.7 A look at the life and work of these two artists will reveal how creative editing and the control of internal rhythm is the central arena for the exercise of their artistic vision.

Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky was born in 1932 in the village of Zavrazhye in Ivanovo Oblast, about 300 miles northwest of Moscow. His mother, Maria Ivanova Vishnyakova, graduated from the Maxim Gorky Literature Institute and worked as a proof-reader for a publisher. His father, Arseny Alexandrovich Tarkovsky, was a famous Ukrainian poet who left the marriage in 1937, when Andrei was five, an event that affected him deeply. During World War II, the family evacuated Moscow to live in the country with his maternal grandmother while his father went to fight in the army (and later returned as an amputee.) These childhood memories, and even a reconstruction of his grandmother’s country house in Yuryevets, reappear in his 1975 film Mirror, which we will examine below.

Tarkovsky studied at the Academy of Sciences, but dropped out to pursue a year-long research expedition to prospect for minerals near the river Kureikye in the remote snow forest north of Mongolia. He decided to study film, applied to V.G.I.K. the state-run Russian film school, and was accepted. Tarkovsky met Andrei Konchalovsky, an emerging screenwriter-director, with whom he would collaborate in his early career. At film school, the two collaborated on the short film The Steamroller and the Violin (1960), which earned Tarkovsky a degree and won the New York Student Film Festival in 1961. The next year, Tarkovsky picked up his first film project, Ivan’s Childhood (1962), a production that was dropped by another director, and the film went on to win the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1962.

In the postwar Stalin era, Soviet film production increased and a new generation of Soviet directors emerged, including Sergei Parajanov and Nikita Mikhalkov. Funded by the state, this new work tended to draw heavily on Russian culture, in part because that tended to be safe material, and in part because these directors, freed from the concern of box office receipts, sought artistic rather than commercial success. In the 1960s, young Russian directors pursued poetic/ artistic films and pushed the limits of state censorship. Tarkovsky’s second feature, Andrei Rublev, was shot in 1965 but quickly ran afoul of the state censors, since it dealt with the topic of artistic freedom under a repressive regime in fifteenth-century Russia. After many re-edits, a version of the film was shown in Venice in 1969, and a censored version was finally released in the Soviet Union in 1971. Tarkovsky’s struggles within the Soviet system were typical, but not as severe as those faced by other directors: Paranjanov’s Shadows of Our Forgotten Ancestors (1965), a story of star crossed lovers set in the rich, colorful Ukrainian culture of the Hutsuls, won him critical acclaim and an immediate hostile assault from the Soviet film industry whose tradition of socialist realism he had violated. Paranjanov was persona non grata in the Soviet film industry from 1965 until 1973, when he was sent to the Gulag for four years on charges of rape, homosexuality and bribery. In this atmosphere of fear and repression, Tarkovsky made Mirror in 1974, a dream-like reminiscence of his childhood. Soviet authorities regarded the film as highbrow art, due to its continuous, nonlinear structure. They sunk the film by limiting its distribution, so Tarkovsky began to pursue co-productions outside the Soviet Union. By 1982, he had completed a feature in Italy Nostalgia, with R.A.I., the Italian national television broadcaster, as the sole underwriter after Mosfilm pulled out of the project. He never returned to the U.S.S.R., and died of lung cancer in 1985 after completing The Sacrifice, a Swedish production that won him a grand jury prize at Cannes.

Tarkovsky and Time Pressure

The centerpiece of Tarkovsky’s written theory is known in English as Sculpting in Time, (literal translation from Russian: Imprinted Time) a term the director uses to describe his filmmaking style. In broad terms, Tarkovsky sees filmmaking as a unique art form, and denies, just as many film theorists do, that cinema’s aesthetic is a composite of other forms like the novel, or painting. Coming from the Soviet tradition, he nevertheless takes a position contrary to Eisenstein (and others) that montage is the primary formative element in cinema. Tarkovsky states directly that there is only one element that is the indispensible aesthetic characteristic of cinema:

The dominant, all-powerful factor of the film image is rhythm, expressing the course of time within the frame. . . One cannot conceive of a cinematic work with no sense of time passing through the shot, but one can easily imagine a film with no actors, music, décor or even editing. . . And I am convinced it is [internal] rhythm, not editing, as people tend to think, that is the main formative element of cinema.8

If this sounds remarkably close to the kind of cinema valorized by André Bazin, it is because, as we shall see, they both can be usefully seen in light of the philosophy of Henri Bergson. Bergson, as we mentioned in Chapter 6, sees time not as a succession of discrete events, but as a constant, unified state of heterogeneous flux that is often experienced by the individual as sped up or slowed down in contrast to conceptual time or time as delineated by a clock.

Not surprisingly, Tarkovsky rejects the idea of collision montage – two shots juxtaposed produce a new, third idea – as contrary to the inherent nature of cinema. And while every art form is “edited” in the sense that materials are selected, assembled and modified, the mere interplay of ideas driven by such “editing” is an unworthy goal for any film that aspires to be art. The traditional plotting of a narrative film Tarkovsky dismisses as nothing more than a “fussily correct way of linking events [that] usually involves arbitrarily forcing them into sequence in obedience to some abstract notion of order. And even when this is not so, even when the plot is governed by the characters, one finds that the links which hold it together rest on a facile interpretation of life’s complexities.”9 He also decries the clichés and crutches used since the silent period by directors who are unwilling to confront their material honestly. If two actions in a film are simultaneous, Tarkovsky says it is an immutable fact that they must be presented sequentially. Tarkovsky notes that some uses of parallel editing in the early period were driven by the lack of sound: he points to a scene from Earth (Dovzhenko, 1930) where the hero is shot, and as he collapses, the film cuts to a nearby field showing startled horses rearing their heads, before cutting back to the dead man. In the silent period, the cut to the horses was needed, because it carried the notion of a gunshot ringing out. With the advent of sound, such a shot is no longer needed, but gratuitous intercutting remains the norm in modern cinema:

You have someone falling into the water, and then in the next shot, as it were, “Masha looks on.” There is usually no need for this at all, such shots seem to be a hangover from the poetics of the silent movie. The convention dictated by necessity has turned into a preconception, a cliché.10

For Tarkovsky, cutting away from the primary action, here, the fall into the river, is a gratuitous relic, a custom that has crept into films where the director is unable to concentrate his vision sufficiently to see the facts before him. In contrast, in Tarkovsky’s method, the authentic film image juxtaposes

a person with an environment that is boundless, collating him with a countless number of people passing by close to him and far away, relating a person to the whole world: that is the meaning of cinema. . . The cinema image, then, is basically observation of life’s facts within time, organised according to the pattern of life itself, and observing its time laws. Observations are selective: we leave on the film only what is justified as integral to the image.11

As a director, Tarkovsky focuses on how that “time within the frame” is constructed: “The cinema image comes into being during the shooting, and exists within the frame. During shooting, therefore, I concentrate on the course of time in the frame, in order to reproduce it and record it. Editing brings together the shots which are already filled with time, and organizes the unified living structure inherent in the film; and the time that pulses through the blood vessels of the film, making it alive, is of varying rhythmic pressure.”12 Again, it is this “time pressure” or internal rhythm created by the director that is the pivotal factor controlling the rhythm of the film, not cutting rhythm. One of the primary methods Tarkovsky uses for revealing time pressure in a shot is by including nature in his mise-en-scène. Tarkovsky relies on life processes and natural phenomena, the texture of their fluctuation, to drive or bolster the internal rhythm of his work, no matter how constructed the setting.

Even though the fires, downpours and gust of wind are staged, re-shot or recreated there still remains the spontaneous element of “nature’s time” within the filmic time. Each of the natural events and elements – water, wind, fire, snow – have their own sustained rhythm. Tarkovsky uses these natural rhythms to express his own, that of his characters and the temporal shape of the film.13

Armed with this method – the control of time pressure within the shot – as the sine qua non of cinema, Tarkovsky proceeds to build a definition of editing around that:

Editing is ultimately no more than the ideal variant of the assembly of the shots, necessarily contained within the material that has been put onto the roll of film. Editing a picture correctly, competently, means allowing the separate scenes and shots to come together spontaneously, for in a sense they edit themselves; they join up according to their own intrinsic pattern. . . Time, imprinted in the frame, dictates that particular editing principle; and the pieces that “won’t edit” – that can’t be properly joined – are those which record a radically different kind of time. One cannot, for instance, put actual time together with conceptual time, any more than one can join water pipes of different diameter. The consistency of the time that runs through the shot, its intensity or “sloppiness,” could be called time-pressure: then editing can be seen as the assembly of the pieces on the basis of the time-pressure within them.14

For Tarkovsky, intercutting actual time – time as we experience it subjectively in one continuously unraveling present that produces an accumulating past, what Bergson calls duration (French: durée) – to conceptual time – clock time, artificially segmented time, time divided arbitrarily in to minutes, hours, days is impossible. For Tarkovsky, these two approaches can never be joined in a film. The central task for the filmmaker is maintaining consistent time pressure across shots, because time pressure is the natural, determining factor for their assembly.

Within his notion of “time pressure” resonates a deeper, philosophical understanding of the power of cinema. Tarkovsky argues that starting from the Lumière film Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1895) cinema gave man the technology to print and reprint time, to take an impression of time and the power to repeat that time over and over on a screen. Cinema gave man “a matrix [a mold] for actual time . . . Time, printed in its factual forms and manifestations: such is the supreme idea of cinema as an art.”15 Here Tarkovsky, like André Bazin, sees cinema’s ability to capture and “mummify” time as part of a fundamental human need to master and know the world, (see Chapter 6, p. 209). Tarkovsky argues that time imprinted in film is the essential reason that people frequent the cinema, not for stories, for stars or for entertainment. Normally, what a person goes to the movies for “is time; for time lost or spent or not yet had. He goes there for a living experience; for cinema like no other art, widens, enhances and concentrates a person’s experience – and not only enhances it but makes it longer, significantly longer.”16 For the modern audience, immersed in a mass culture of consumerism that is spiritually crippling, that creates barriers to engaging the deep questions about the meaning of our existence, artistic films will strive to concentrate the continuous time of human consciousness, thereby bring the audience closer to the truth.

Obsessed with this actual time, the time of human consciousness that cannot be paused, Tarkovsky offers us some cryptic glimpses of his understanding of that concept: “Time is necessary to man, so that, made flesh, he may be able to realize himself as a personality. . . Time is a state: the flame in which there lives the salamander of the human soul.”17 This rich metaphor associates salamanders with fire, because in Russian folklore salamanders were thought to be impervious to fire. In fact, salamanders are all poisonous to humans if ingested since they secrete toxins through their skins. They were nevertheless used to make “salamander brandy,” a drink supposed to have hallucinogenic or aphrodisiac properties that is created by immersing live salamanders in fermented fruit juice. Here, Tarkovsky conjures the almost mystical nature of actual time.

A key part of that mystery is human memory, accumulating as time moves forward. Tarkovsky writes, “Time and memory merge into each other: they are like the two sides of a medal. It is obvious enough that without Time, memory cannot exist either. But memory is something so complex that no list of all its attributes could define the totality of the impressions through which it affects us. Memory is a spiritual concept!”18 Like Bergson, Tarkovsky is suggesting that the subjective experience of time is participation in a constant flux that moves indivisibly between present and past. Clearly, the long take is one way cinema can represent the unfolding present with fidelity,

but a complete cinematic interpretation of Bergson’s duration would also include editing that links past/present, memory/perception, fantasy/reality, and dream-time/real-time. In short, inner and outer reality. Indivisibility can also be represented by a cutting and narrative style that does not call attention to these shifts in time and realms of reality (as they are not codified in consciousness) . . . Tarkovsky’s films require several viewings before one can make easy separations between the inner (mind) and outer (social/physical reality) world. This is what characterizes Tarkovsky’s narrative structure as durational.19

For Tarkovsky, then, the first aesthetic choice is the use of cutting that minimizes or masks temporal ellipses and avoids juxtaposition, a choice that moves his films closer to the uninterrupted living flux of actual time.

The moving camera is Tarkovsky’s second aesthetic choice for exploring duration, because, as many theorists have noted, the moving camera “temporalizes space:” that is, represented space loses its static homogeneity as the camera travels through it, much like a Cubist painting that tries to represent space from a number of different perspectives.20 A moving camera and the seamless editing of moving shots is Tarkovsky’s method to transport the viewer freely through a range of times, in the same way that we experience dreams, moving forward and unstoppable. Or as Donato Totaro puts it, “Our true inner self, our emotions, thoughts, and memories do not lie next to each other like shirts on a clothesline but flow into one another.”21 A few examples will indicate how these choices work in Tarkovsky’s Mirror. See Critical Commons, “The Mirror: Time Pressure and Découpage in Oneiric Cinema. Fire, Leaves, Shower.”22

The nonlinear narrative of Mirror (1975) captures the remembrances of a dying poet, Alexei, or Alyosha (Ignat Daniltsev). The character is loosely based on Tarkovsky’s father Arseny, and some of his poetry is included as voice over in the film. The film reveals key personal and historical moments from three time periods: the narrator’s childhood in the countryside before World War II, the war period and after the war in the 1960s or 1970s. The film includes biographical details of Tarkovsky’s life, such as the fact that his mother was a proofreader in a printing shop and that they were evacuated from Moscow to the surrounding countryside during the war. Part of Tarkovsky’s intentional blurring of these time periods is casting the same actress, Margarita Terekhova, as Alexei’s mother and wife.

An early scene in Mirror takes place before the war where Maria (Terekhova) has given breakfast to two children (Alexei’s siblings?), and she stares off camera, contemplating something, gently crying while a love poem is read in voice over. A commotion erupts outside of the dacha, with people shouting and a dog barking. Maria walks to see what is the confusion is, then calmly returns to tell the two children, “It’s a fire. Don’t shout.” The children rise and exit to see what is happening. After they exit, the camera pulls back slowly and a bottle falls off the table; auto kinetic objects are a running motif in the film. The camera pans left to reveal a mirror in which the two children can be seen standing at the screen door, out of focus, but with a blaze beyond them outside. As the camera racks the fire into focus, a young Alexei walks into frame, and the camera follows him outside to the porch. The camera continues to glide right, revealing a huge fire engulfing a barn. Rainwater pours off the porch roof in the foreground as a man in a hat and woman in a headscarf, their backs to the camera, look on impassively as the immense fire rages. The inference in the moment is that the woman is Maria – she just exited from this space – and this inference seems to be confirmed when Alexei, wearing the same shearling coat he had on inside the dacha, walks from the porch into the frame. The timing of his movement off the porch relative to where she stands seems to be about the right “temporal separation” of the two figures.

But the next cut shows Maria nearby – she doesn’t have a headscarf on, and she never did – standing relaxed with her arms crossed, looking frame right, the sound of the fire (or is it dripping water?) continuing outside the frame. She casually walks forward, and the camera follows, tracking her to a well where she stops to splash her face from the bucket, and then sits down on a wall surrounding the well. Spatially, this shot is difficult to integrate with earlier shots, since the earlier inference – even if it was in the moment, almost subliminal – was that Maria was standing closer to the fire in the previous shot. As Maria now sits calmly at the well, the camera is carefully framed so that no fire is shown: Tarkovsky is withholding the excitement of the fire from the audience. A man in boots and a hat calmly walks into frame and the camera slowly tilts up to reveal that the barn (the same barn?) is still burning intensely. But something is off: the spatial arrangement of the fences and the barn are different from the previous shot, adding to the scene’s spatial ambiguity.

As the man begins to run closer to the barn, the film cuts to the young Alexei sleeping in his bed. The typical inference from this juxtaposition is that the fire shown before is an “unmarked” dream sequence. But as the boy wakes and sits up in bed, Tarkovsky cuts to a black and white shot of beautiful underbrush, which, blown by a rising wind, ripples in slow motion as the camera tracks away, a typical strategy he uses to display “time pressure.” Shots of fields mysteriously blown by the wind are a running motif in the film and here break any narrative arc with pure movement. The next cut comes quickly, returning to Alexei in essentially the same position again sleeping, but this time in black and white. He wakes and sits up again, just as he did before, although it seems to be morning in the bedroom now. Alexei rises and tiptoes to the next room, and as he peers in through the door, an object (a cloth, a towel?) flies across the top of the doorway. The film cuts instantly to Alexei’s father, as he pours water in slow motion over a woman’s hair. The woman slowly rises, her face hidden by wet hair. She stands dripping, and the film cuts to a shot framed so closely to the outgoing shot that the woman “pops out” of frame as water cascades from the ceiling in slow motion. The camera holds the long shot as soaked plaster slowly breaks and falls to the floor. A cut to medium shot of the woman shows her walking and tousling her wet hair in slow motion. She lowers her arm, revealing it is Maria, as the camera pans from her to her reflection in to a mirror with water cascading down one edge. The pan continues to the left, where a well disguised cut in black carries the pan to another shot that comes to rest on an exterior doorway where Maria inexplicably enters from outside. As Maria steps forward towards a mirror, her reflection appears as an older woman (played by Tarkovsky’s mother Maria Vishnyakova) with a landscape seen through an arched window – or perhaps a landscape painting of the same –superimposed over it. The old woman/Maria walks forward and wipes haze from the mirror, and the scene cuts to a recurring shot of a hand that is at first glance appears to be on fire, but then is seen to be cupping a burning stick. (Tarkovsky next cuts to a room and a phone rings, a scene we will take up again shortly.)

Excluding the “hand-on-fire” shot (:03 seconds long) at the end, which is a recurring, interstitial, symbolic shot in the film, the average shot length of this sequence is:37 seconds. The shortest shot is of the plaster falling at:13 seconds, and the longest apparent shot is of Alexei walking outside to see the fire at:59 seconds (though there appears to be a very well disguised cut in this shot, it is unlikely to be seen on first viewing.) Two other shots are close to a minute long: the shot where Maria walks to a well and sits (:53 seconds) and the shot where Maria washes her hair (:52 seconds).

Throughout the scene, the interplay of these long takes with the flexible, “rubbery” time pressure within them seems slightly off-kilter. The relaxed stroll that Maria takes to sit down at the well and watch the barn burning, the slow motion hair washing and plaster falling (Figure 7.1), the slow, deliberate movement of the old woman towards her reflection at the end of the episode all feel emotionally slowed down, like movement retarded in space that is “thick” and restrictive. Vlada Petric sees this unease as part of a tradition in the Russian arts to highlight the subjective experience of the work:

The phenomenological signification of Tarkovsky’s oneiric vision rests on an interaction between the representational and the surreal: the viewer feels that something is “wrong” with the way things appear on the screen, but is incapable of detecting sufficient “proof” to discredit presented events on the basis of every day logic. As a result, the shot is “estranged” poetically in the best tradition of the famous Russian Formalist poets and Constructivist artists, who insisted that viewers always be aware of experiencing a work of art as a subjective transposition of reality.23

Figure 7.1 Mirror (Tarkovsky, 1975): slow motion. In Mirror, Alexei rises from his bed to discover his mother washing her hair – shot in slow motion. The shot is almost a minute long, and the interplay of the long take with the “rubbery” time pressure within is part of a strategy by Tarkovsky to render the scene slightly off kilter.

Source: Copyright 1975 Mosfilm.

This tension between Mirror’s representational and estranged elements is a way to ensure that a scene’s meaning is not predetermined for the viewer. In the shower scene, this ambiguity is reinforced at the end of the scene when Alexei’s mother is “transformed” from a young woman into an old woman by a cut on action as she moves towards a mirror. As she “wipes steam” from the mirror, nothing changes – her image remains in a sort of soft, “cobweb” reflection that will not “clarify.” Her hand appears solid and in crisp focus while her image is indistinct and enshrouded (Figure 7.2).

This extended moment is followed by a cut on idea, from her hand motion to the “flaming hand” shot that recurs throughout the film (Figure 7.3), a punctuation at the end of the dream that suggests a symbolism that Tarkovsky himself would deny. Tarkovsky says, “I had the greatest difficulty in explaining to people that there is no hidden, coded meaning in the film, nothing beyond the desire to tell the truth. Often my assurances provoked incredulity and even disappointment. Some people evidently wanted more: they needed arcane symbols, secret meanings.”24 Thematic ambiguity is central to Tarkovsky’s work, and is nowhere more apparent than Mirror. The viewer, forced to deal with narrative uncertainty and cutting that seems vaguely symbolic, finds in Mirror

Figure 7.2 Mirror (Tarkovsky, 1975): cut on idea from hand . . .

Figure 7.3 Mirror. . . .to a recurring interstitial shot of a hand .a cut on idea to the “flaming hand” shot that recurs throughout the film, a suggestion of symbolism that Tarkovsky consistently denies in his work.

Source: Copyright 1975 Mosfilm.

the same kind of slippery, disorganized meaning that we encounter with dreams after waking reflection.

As if to confirm this commitment to ambiguity, in the scene that follows the “flaming hand” shot, the phone rings. Alexei answers, though the film shows only camera movement through his apartment. He has a phone call (entirely off camera) with his mother. He tells his mother he just had a dream about her and asks two questions: when did his father leave them, and when did the barn catch on fire? She answers each time, “1935.” Alexei, having dreamed about the barn burning, wakes to associate that event with his father leaving. Somehow, in Alexei’s dream and in his memory, there is a kind of “subjective transposition” of these two events. Tarkovsky will only reveal that Alexei has made the transposition, without any hint as to its meaning.

In a second oneiric scene set during wartime, Alexei and his mother Maria return to a dacha that her stepfather previously owned to speak to the woman there about a private matter. See Critical Commons, “Mirror: Time Pressure and Découpage in Oneiric Cinema. Earrings, Cockerel, Bed.”25 Maria drops a small coin purse on the floor that she has brought with her, and a ring and a pair of blue stone earrings rolls on to the floor. Maria and the woman move to an adjacent room, and the boy has to wait in the living room while they speak privately. He stares at himself in a mirror. A close up of embers in the fire tilts up to a mirror propped in the fire whose hazy reflection shows a young boy. A hand closes a door very, very slowly, and the natural inference is that it is the woman closing the bedroom door so that she and Maria can converse in private. But when the door is finally pulled into its latch, the camera seems to have tracked left to reveal a young Maria nursing the infant Alexei by a fire. Here, Tarkovsky repeats a striking shot seen earlier of a hand that appears to be aflame – in actuality, the hand is simply in front of a flaming stick.

Alexei turns to see a kerosene lamp sputtering out, and close shots follow of his mother and the woman speaking (their lips move but there is no sound but dripping water). The woman tries on the blue earrings. Her headband, the earrings and the Rembrandt style lighting of the scene, strongly suggest the Vermeer painting “Girl with a Pearl Earring.” The lighting is very selective, so the spaces are very dark and indeterminate. The woman with the blue earrings circles Maria, and their conversation ends as she steps forward into the darkness, a hidden cut in black resolves to an incoming pan shot and rack focus back to the boy deep in thought. His mother and the woman emerge from the adjacent room, relight the lantern, and then go to see the woman’s angelic young baby, who sleeps on a drapery-covered bed. The baby awakens.

Maria moves to the kitchen with the woman with the blue earrings, and the subtext of the dialogue reveals that Maria has come a long way, trying to pawn the earrings. The woman asks Maria to slaughter a cockerel for dinner, since she is pregnant and even milking the cow makes her queasy. She brings the bird in, places it on a wooden chopping block, and hands Maria a sharp ax. Tarkovsky cuts to a close up of the woman, who waits for Maria to strike the bird. There is a squawk off camera and feathers float onto the woman. A cut back to Maria in close up shows her face, eyes down, lit from below eyelevel and shot from below eyelevel, in a classic, threatening horror film composition. She casts a sly glance off camera towards the woman, and the viewer slowly realizes that she is photographed in slow motion. Maria turns to address the camera (and the audience), with an enigmatic, disturbing look on her face. She holds that position for a full eight seconds (Figure 7.4). If the slow motion and underlighting are not enough to “estrange” this shot for the viewer, the hold and the cut that follows certainly do.

As the mother addresses the camera – and the viewer – for what seems like an eternity, the film cuts to a matched black and white shot of Alexei’s father, also addressing the camera (Figure 7.5).

Figure 7.4 Mirror (Tarkovsky, 1975): shifting modes of address, from looking at the audience to. . . In Mirror, an extended shot of the mother in slow motion addressing the camera at first feels like she is looking at the the audience, but as the film cuts to . . .

Figure 7.5. . .looking at the father in some other place and time.. . .a matched reverse shot of the father in black and white, Tarkovsky is recreating the shifting, disorganized time and space of dreams.

Source: Copyright 1975 Mosfilm.

Given that the camera placement is carefully matched – he is shot from slightly above eye-level and centered – the film strongly suggests she is staring at him, and that he is spatially proximate. Ultimately, the matched cut to black and white marks a sudden shift – she is not looking “at us,” the viewers, but “at him” in the future or the past, or “at him” in a dream. Here again, Tarkovsky is playing with the kind of disorganized time and space that we encounter with dreams, to the same end: he is thwarting any attempt to impose a narrative logic on his more pointed cuts. The scene ends as the father holds, and then turns in slow motion, stroking the hand of a reclining woman, telling her not to fret. The camera tracks right revealing that Maria is the reclining person he is touching, and when the camera pulls back, that she is floating above the bed, speaking to him as if in a dream, “Don’t be so surprised I love you.” A white dove flits momentarily across the upper right corner of the screen, and the scene ends.

Mirror’s mise-en-scène moves effortlessly between the present and the past, shifting freely from remembered past to living present, from imagined world to real world. Long takes, the assembly of those takes, and the precise control of time pressure within his films allows Tarkovsky to emulate the subjective, organic flux of actual time. And in the process, the flux created by Tarkovsky in Mirror reconstructs “the lives of people whom I love dearly and knew well. I wanted to tell the story of the pain suffered by one man because he feels he cannot repay his family for all they have given him. He feels he hasn’t loved them enough, and this idea torments him and will not let him be.”26

Tarkovsky has an almost fanatical faith in the power of cinema to give people the living flux of time because cinema is not stars, nor entertainment, nor stories. Only by remaining true to actual time, undivided time, time lived subjectively, can the filmmaker give the audience a concentrated experience of life. And so it follows that the essence of a director’s work boils down to the English title chosen for his book, Sculpting in time.

Just as a sculptor takes a lump of marble, and, inwardly conscious of the features of his finished piece, removes everything that is not part of it – so the film-maker, from a “lump of time” made up of an enormous, solid cluster of living facts, discards what ever he does not need, leaving only what is to be an element of the finished film, what will prove to be integral to the cinematic image.27

Maya Deren

Maya Deren was born Eleanora Derenkowsky in 1917 in Kiev, Russia and emigrated to the United States in 1922 with her father, Solomon Derenkowsky, a psychologist, and her mother Marie Fiedler to escape the anti-Semitic pogroms of the period. Her father shortened the family name to Deren when they arrived in Syracuse, New York, and he quickly learned English and took medical classes at Syracuse University. He passed his American medical exams within two years of coming to America, and became the staff psychiatrist at the State Institute for the Feeble-Minded in Syracuse. A prolific writer from an early age, Eleanora moved with her mother to Geneva, Switzerland to study at the League of Nations International School from 1930 to 1933, and entered Syracuse University at age 16. She married the socialist organizer Gregory Bardacke at age 18, moved to New York City and divorced him three years later. Deren earned a degree in literature from New York University, and later a master’s degree from Smith College at age 21. Her thesis was entitled The influence of the French Symbolist School on Anglo-American poetry (1939).

After moving to Greenwich Village, Maya worked as a freelance photographer and then as a manager and publicist for the choreographer Katherine Dunham. Dunham was studying Caribbean dance and culture, and had recently completed her own master’s thesis in anthropology on the Haitian dance using 16mm film to capture dances and some of the ceremonies for her research. The work with Dunham kindled Deren’s life long interest in Haitian rituals and the Haitian religion Voudoun, a uniquely Caribbean synthesis of West African cosmology and polytheism with European Catholicism. Beginning in the late 1940s, Deren travelled four times to Haiti to document Mardi Gras, drumming, dance and Voudoun ceremonies, from which she produced numerous articles for magazines, a record album entitled “Voices of Haiti” and a book, Divine horsemen: the living Gods of Haiti. At the end of a tour with the Dunham troupe, Deren stopped in Los Angeles for several months, and met Alexandr Hackenschmied (later Hammid), a still photographer and accomplished motion picture cameraman from Czechoslovakia who became her second husband a few months later in 1942. Hammid would collaborate with Deren on perhaps her most famous film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), during which time Deren also adopted the pet name Hammid used for her – “Maya.” He would go on to make numerous documentary films including To Be Alive for the 1964 New York World’s Fair, a film that won him an Academy award for Best Documentary Short. The couple were married from 1942 to 1947, and their collaboration fed Deren’s interest in filmmaking, trained her in camera and editing techniques, and guided her emerging vocation as an independent filmmaker.

From 1943 to 1948, in an extraordinary burst of inspiration, Deren made five films that are among the most significant experimental films made in the United States. Her body of work is characterized by creative use of the camera to enliven space through the power of movement, and the transformation of time and space through imaginative editing. Deren used the cut on action to continue motion across discontinuous spaces, as well as jump cutting, slow motion, multiple exposure and super imposition to transform the viewer’s ingrained notions of time (duration) into films of dream-like, stream of consciousness. Her films also became the basis for her independent distribution business, Maya Deren Films. She rented her films to museums, schools and film societies around the world, covering all of the tasks associated with the enterprise: Deren handled the shipping and billing, wrote the brochure copy, printed the promotional stills and even the program notes to accompany the films, such as this one written in the third person from 1950:

As a finished product, Maya Deren’s films – with their haunting poetic images, their unorthodox filmic concept and techniques – are in themselves quite extraordinary. But even more extraordinary, perhaps, is the fact that Maya Deren is all things to her films – writer, producer, director, actress, light man, editor, and distributor. Moreover, since such non-commercial films, like any other art form, do not provide substantial remuneration, she has extended her versatility even further and has gained a considerable reputation as a still photographer, lecturer and writer, not only on films but on a variety of subjects including cats, ethnic dance, etc. Lately she has become known particularly as an authority on Haitian dance, music and mythology.28

As Renata Jackson points out, the claim of being a one-woman show is an exaggeration, since all of her films excluding her last one, Meditation on Violence (1948) were made with the contributions of Hammid and Hella Hyman, and her distribution business was often manned by friends when she was travelling.29 But the singularity of vision and the determination to make films in the absence of “substantial remuneration,” was part and parcel of her bohemian lifestyle and self-made career as an independent film artist.

Like Eisenstein, Maya Deren was a filmmaker and a film theorist. She wrote extensively for journals and popular magazines, and produced a book length treatise, An anagram of ideas on art, form and film published in 1946 that has been generally overlooked as a serious work of film theory. The book validates the foundations of Deren’s creative work, and explores the full range of her ideas including “classical form, the essential properties of film in movement and temporality that lead Deren to explore the intersections of film and dance, her opposition to documentary film, ‘vertical’ versus ‘horizontal’ structure, the idea of art as ritual, and the moral imperative underlying artistic production.”30 Deren’s theorizing was a clarion call for a new kind of cinema, and ran parallel to Eisenstein’s

in their insistence on the grounding of this cinema in a solid basis of theory, in their reference to other disciplines and forms of artistic practice. Of major importance as well was their grounding in theatrical (and choreographic) movement and gesture, their adventurous forays into other cultures, their interest in ritual, and the manner in which their production is crowned by ambitious and uncompleted ethnographic projects – Eisenstein’s in Mexico, Deren’s in Haiti.31

Later in her life, Deren was critical of Hollywood’s economic, artistic and political dominance of the cinema, and particularly of the narrow mode of production that limited the creative exploration of forms other than narrative. Deren once told an interviewer, “I make my pictures for what Hollywood spends on lipstick,”32 a statement that summarizes how marginalized she felt as an experimental filmmaker during her lifetime. To expand film’s potential and oppose the dominance of Hollywood, Deren urged emerging film artists to abandon narrative, and to embrace dream, ritual, myth and magic: “Instead of trying to invent a plot that moves, use the movement of wind, or water, children, people, elevators, balls, etc. as a poem might celebrate these. And use your freedom to experiment with visual ideas; your mistakes will not get you fired.”33 Maya Deren died suddenly at age 44 in 1961 from a brain hemorrhage. A look at her first and perhaps most powerful film, Meshes of the Afternoon, will illustrate her exploration of space and time to create oneiric, ritual structures in film.

Maya Deren and Meshes of the Afternoon

The first collaboration of Maya Deren and Czech cinematographer Alexandr Hammid, Meshes of the Afternoon, is one of the most widely seen and historically significant experimental films of the twentieth century, a film that was influential in the emergence of American avant-garde film in the 1960s. While Meshes clearly deals with a dream or trance state, and its overall form is circular and oneiric, Deren was unequivocal in disavowing its connection to the larger surrealist movement, with its emphasis on signification through chance juxtaposition. For years, she rejected as excessive the numerous Freudian, psycho-sexual interpretations of Meshes, and for a time, stopped showing the film because she thought it was being analyzed in these terms well beyond her intent. In 1959, 16 years after it was created, she added an “impersonal” score to the film, written by her third husband Teiji Ito. Deren was hoping to

reinforce the depersonalized character of Meshes and save it from “the rapacious analysis” under which it had suffered since 1943. . . But while the presence of Oriental instruments does provide an interesting contrast to the film’s west coast milieu. . . Teiji Ito’s score cannot “off-set” the intersection between the represented actions or objects in our understanding of them through a Freudian paradigm: the vaginal connotation of the flower and the woman’s placement of it on her lap; the phallic connotations of the knife and the key; the visual connections made between the lover and the figure in black; figure in black as a symbol of death; the association between sex and death.34

While these Freudian overtones are hard to deny, Deren’s intent to thwart any narrative arc driven by character is clear. The female figure is shown initially only as a shadow, and at points where traditional cutting would show her face – notably, a shot of her feet crossing the threshold of the house and coming to a stop would ordinarily be followed by a close up of that person – there is none.

The female figure’s face is not shown (excluding an extreme close up of her eye) until over four minutes of the film have elapsed. Subjective, P.O.V. camera movements “looking throughout the house” are not “answered” with reverse shots of the person whose P.O.V. is represented. Further, the introduction of a second figure that is masked continues Deren’s intentional “disembodiment” of character. For all its Freudian symbols, Meshes tends to neutralize any tendency from the audience to identify with character, so the circular, repeated, choreographed route of the female figure dominates: the ritual of this journey is, in the end, about all the “character development” viewers are left with.

Meshes opens with a mannequin’s hand descending from the top of the frame to deposit a flower on a sidewalk that climbs up a hill. The film shows the shadow of a female figure picking up the flower, turning to her left into an opening in a stucco wall, climbing some steps and struggling to get a key to open the door. The establishment of this opening space – the rising sidewalk, the steps that lead off of it and the door close by – is clear, and classically constructed cinematically. It will recur four more times in the film, three as the female figure turns from the sidewalk to enter the door, and once at the end when the male figure does the same. The female figure enters the house. Subjective camera movement carries her to the kitchen table, where a knife resting half way through a loaf of bread falls auto kinetically to the table. The camera then moves on to a telephone lying off the hook on the stairs, and up the stairs to an empty bedroom where a phonograph plays. There is a moment of spatial disorientation when, without re-establishing the female figure’s position, her hand abruptly enters the frame to stop a phonograph record. A whip pan moves away from the phonograph, and a hidden cut within the pan takes the subjective camera downstairs. See Critical Commons, “Meshes of the Afternoon: Female Figure Dreams.”35

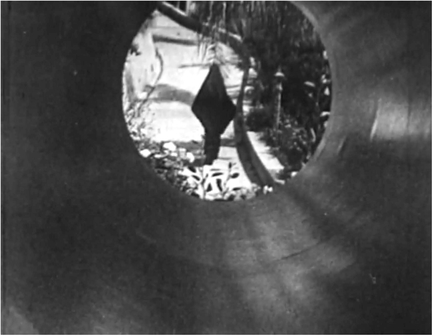

The female figure falls asleep on a stuffed chair by the window. For all of Meshes’ creative, experimental construction, Deren reverts to another classical cinematic figure of style here by using traditional, repeated markers for the dream sequence, altered with simple effects. The beginning of the dream is marked by four cuts: an extreme close up of her eye (cut to) the sidewalk seen out the window as a veil or thin gauze descends over the lens (cut back to) the extreme close up of her eye as a veil or thin gauze descends over the lens (cut back to) the sidewalk seen out the window, as the camera pulls back into a tunnel-like pipe and a hooded figure enters the frame (Figure 7.6). Here, the low-tech effects created in front of the lens became a prototype that many experimental filmmakers would follow, an effective “hands-on” gesture that transforms the dominant editing forms of Hollywood cinema for personal expression.

The next scene returns to the sidewalk as the figure in black turns to reveal a “mirror face,” and then continues up the hill. The film crosscuts back and forth between the female figure’s shadow running up the hill in real time, and the figure in black ascending the hill in slow motion, with two cleverly disguised cuts within whip pans creating a seamless transition between the two camera frame rates. A panning shot of the female figure’s feet again reveals the earlier geography of the steps that open in the stucco wall, and the female figure climbs the steps and re-enters the house. A kind of ritual is emerging: the female figure can pursue the figure in black up the hill only so far before turning away to return to the house. By masking the figure, Deren attempts to “depersonalize” one of the central characters, and move Meshes away from a film of strictly personal expression, an idea she associates with the romantic notion of the artist, struggling to express his own personal preoccupations. Deren mistrusts this romantic ideal, writing in Anagram,

Accustomed as we are to the idea of a work of art as an “expression” of the artist, it is perhaps difficult to imagine what other possible function it could perform. But once the question is posed, the deep recesses of our cultural memory release the procession of indistinct figures wearing the masks of Africa, or the Orient, the hoods of the chorus, or the innocence of the child virgin. . . the face is always concealed, or veiled by stylization – moving in formal patterns of ritual and destiny. And we recognize that an artist might, conceivably, create beyond and outside all the personal compulsions of individual distress. . . it becomes important to discover how and why man renounced the mask and started to move towards the feverish narcissism which today crowds the book-stores, the galleries, and the stage.36

Figure 7.6 Meshes of the Afternoon (Deren, 1943). In Meshes of the Afternoon, Maya Deren signals the beginning of a dream state by a low-tech effect created in front of the lens: the camera dollies back inside a metal pipe.

Source: DVD copyright 2002 Mystic Fire Video.

While Deren wrote very little about ritual in her theory, she sees the use of masked figures and un-individuated, almost Jungian archetypes as part of her strategy to broaden the reading of her films beyond the narrow Freudian interpretations that so often greeted her work.

Moreover, the creative camera work and deft editing of this scene exemplifies Deren’s poetics of cinema, as expressed in Anagram, that creative filmmaking involves both the camera – as a tool of discovery – and editing – a tool of invention. Filmmaking is an

instrument composed of two separate but interdependent parts, which flank the artist on either side. Between him and reality stands the camera. . . with its variable lenses, speeds, emulsions, etc. On the other side is the strip of film which must be subjected to the mechanisms and processes of editing (a relating of all the separate images), before a motion picture comes into existence. The camera provides the elements of the form, and, although it does not always do so, can either discover them or create them, or discover and create them simultaneously. Upon the mechanics and processes of “editing” falls the burden of relating all of these elements into a dynamic whole.37

In this scene, the use of the sidewalk and steps as a circular, ritual landscape, the subjective camera moves and the extreme close up of the eye rely on the camera’s ability to discover. The use of gauze over the lens, the tunnel shot and the use of slow motion rely on the camera’s ability to create. The tight structuring of an editing “figure of style” to cue the viewer to the dream state, the invisible cuts within footage to shots of different frame rates and the repeated action of turning away from the ascending sidewalk to the stairs rely on editing’s ability to invent a dynamic structure from the elements the cam era provides. See Critical Commons, “Meshes of the Afternoon: Female Figure Tumbles.”38

As the female figure returns up the steps to the door, the camera shows her face for the first time. She again sees the knife, and ascends to the bedroom through a veil to find the phone off the hook lying on the bed. Pulling back the bed covers reveals the knife again, a moment punctuated by an extreme close up of her distorted reflection moving across the blade. The force of that moment seems to propel the female figure backwards across the veil she entered through. A series of seven spatially disorienting jump cuts in the stairwell follow, cuts that capture her dream-like “tumble down the rabbit hole” until she emerges through an archway. In a subjective shot from that position, she scans the room, returning to the chair by the window, where she sees herself sleeping once again. The circular structure, the ritual procession/return of the female figure to the chair is another part of a strategy of “depersonalization” of the central figures in Deren’s films. “The ritualized form treats the human being not as the source of the dramatic action, but as a somewhat depersonalized element in a dramatic whole. The intent of such depersonalization is not the destruction of the individual; on the contrary, it enlarges him beyond the personal dimension and frees him from the specializations and confines of personality.”39 A remarkable cut on action takes the female figure “flying” forward from the high arch to a moving shot of her hand “landing” at the phonograph, returning her to the ground level of the house, ending a sequence with a travelling camera that creatively mimics the dream-like feeling of tumbling and floating through space.

The next section of Meshes uses low-tech, creative filmmaking techniques that echo, in many ways, the early work of the French stage illusionist turned “trick-film” maker, Georges Méliès (1861–1938). These effects center on doubling the female figure within the same frame, the use of the stop-motion substitution effect, and the eye-line match or referential cut to create the impression that the female figure is looking at herself. In this “third round” of the journey through the house, the female figure will witness herself in multiple, dream-like paths that bring her into a face-to-face confrontation with herself. The sequence opens with the female figure rising from the phonograph, and as she stands up, she turns into a profile shot, a startling moment that reveals the female figure doubled in the frame, a duplication that suggests her active, “dreaming spirit” is rising from her body, still sleeping in the chair. An in-camera split screen creates the effect, which was a trick known from still photography and adopted in the earliest days of cinematography by filmmakers like Méliès. The image is created by locking down the camera, making note of the starting frame, masking one side of the frame while exposing the other, rewinding to the start and reversing the mask to expose the portion of the frame that was masked off in the first pass.

In the next four shots, the female figure standing at the window is intercut with point of view shots from the window: the female figure touches the window and looks down (cut to), a subjective shot from the window, the hooded figure carries a flower and moves up the sidewalk and she runs after him (cut to), the female figure is still touching the window, her eye-line following the action below (cut to), the hooded figure moves up the sidewalk and she hurries to follow him, coming once again to the steps where she turns away, back towards the house. In a tight close up, the female figure pulls a key from her mouth, a surreal, “sleight of hand” that is simultaneously a “visible utterance” of entry and passage. The film cuts to the female figure entering the door, and the third round of her journey up the stairs – this time rocked by earthquake-like movements of the stairs – takes her again to the bedroom, where the hooded figure lays the flower on the pillow See Critical Commons, “Meshes of the Afternoon: Female Figure ‘Pops’ In/Out and Multiplies.”40 As she looks on, the hooded figure pops out of the frame using a Méliès-style stop-motion effect, setting off a series of 11 stop-motion-like jump cuts that “animate” the female figure down the stairs and back up again. In the next series of shots, which presumably are upstairs, the female figure eyes the knife in close up, and when she looks off out of frame, the camera tilts up to reveal that she is once again by the chair at the window, looking at herself asleep. Deren, writing about her early work, notes that this kind of uncanny movement creates the feeling of a dream state. “[T]he central character of these films moved in a universe which was not governed by the material, geographical laws of here and there as distant places mutually accessible only by considerable travel. Rather, he moved in a world of imagination in which, as in our day or night-dreams, a person is first one place and then another without traveling between.”41

As the female figure returns again to the window, the fourth round of pursuing the hooded figure up the sidewalk ends as it has before: with another turn to the steps, another key pulled from her mouth, which is immediately transformed by stop-motion substitution into a knife. This time, as the female figure enters the house, she carries a knife, only to find two more versions of herself seated at the table (Figure 7.7), where the bread was seen earlier. Lucy Fischer notes that this “multiplication” of the filmmaker is also an early trick film technique used by Méliès who once played seven different people in the same shot in The One-Man Band (1900). Fischer continues, “That Deren’s films and writings would be informed by a sense of magic should come as no surprise to us. Born Eleanora, she changed her name to Maya, in honor of the Hindu goddess of sorcery. Beyond that, Deren’s poetry and theoretical musings on art and cinema were laden with references to prestidigitation.”42

Figure 7.7 Meshes of the Afternoon (Deren, 1943). Deren uses an early trick film technique to multiply the female figure within the frame for a game of “drawing straws.” In this way, Meshes is closer to the screen magic of the pioneer filmmaker Georges Méliès, trying to persuade us that the dream/ ritual before our eyes is real.

Source: DVD copyright 2002 Mystic Fire Video.

Filmic prestidigitation is precisely what follows. With three versions of the female figure around the table, a game of “drawing straws” commences. Placing the knife on the table, it is instantly transformed into a key by stop-motion substitution. The key is picked up from the table, shown to the other players, only to be “popped” back into place on the table by stop-motion substitution. The spatial relations here are quite explicit, with traditional matched eye-lines in the two-shot and in the single of the female figure who entered the house, indicating it is now the latter’s turn to play. Reaching for the key, she turns her hand over to reveal that her palm is black, and a quick stop motion substitution transforms the key back into a knife. The two female figures react in shock, a whip pan disguising the cut between their two positions.

The female figure rises, holding the knife, now with her eyes obscured by silver orbs. A matched cut on the action of her standing uses creative geography to take her outside, and five matched profile shots of her feet walking show her advancing ominously towards the sleeping figure on the chair by the window. The cuts make the foreground action read as temporally continuous, but spatially, each shot is different. In a 1955 letter to James Card of the George Eastman House, Deren wrote about this remarkable sequence,

There is a very, very short sequence in that film [Meshes] – right after the three images of the girl sit around the table and draw the key until it comes up knife –when the girl with the knife rises from the table to go towards the self which is sleeping in the chair. As a girl with a knife rises there is a close-up of her foot as she begins striding. The first step is in sand (with suggestion of sea behind), the second stride (cut in) is in grass, the third is on pavement, and the fourth is on the rug, and then the camera cuts up to her head with the hand with the knife descending towards the sleeping girl. What I meant when I planned that four [sic] stride sequence was that you have to come a long way – from the very beginning of time – to kill yourself, like the first life emerging from the primeval waters. Those four strides, in my intention, span all time. . . That one short sequence always rang a bell, a buzzer in my head . . . And so [I] came to the world where the identity of movement spans and transcends all time and space. . . here is continuity, as it were, holding its own in a volatile universe. . . that movement, or energy is more important, or powerful than space or matter – that, in fact, it creates matter – seemed to me to be marvelous, like an illumination that I wanted to just stop and celebrate.43

Here, the creative geography of matched action, the deliberate, trance-like walk across the flux of discontinuous space lends an allegorizing quality to the female figure’s journey of aggression. The spatial/temporal transformations continue as the female figure appears to be lowering the phallic knife into the sleeping woman’s mouth, which jolts her awake, her eyes wide in an extreme close up, as a shadow passes over her face. A close up of a man withdrawing from her follows, from her point of view, as if he had just kissed her.

From this point forward, the man replaces the hooded figure, leading the female figure upstairs to the bedroom, putting the phone back on the hook, placing the flower on the bed. The female figure lies on the bed, her head on the pillow next to the flower, and the man caresses her and moves towards her. The flower magically “pops” into a knife. An extreme close up shows her eye glancing towards it and as they hold the moment of confrontation, she strikes and his image shatters like a mirror, revealing the ocean behind. The journey up the sidewalk now resumes for a final time, only this time with the man striding up the steps to the door, picking up the flower, turning the key to find the female figure in the chair slashed and bloodied, surrounded by the broken shards of a mirror. This is the circular ritual brought to its final conclusion.

After Meshes, Deren maintained “the function of film, like that of other art forms, was to create experience – in this case, a semi-psychological reality.”44 But as Renata Jackson points out, Deren’s theorizing about her later work shifted: she began to see the proper goal for cinematic art as the manipulation of space/time through purely filmic means, rather than methods that look to literature or drama. By the time she wrote her theoretical treatise Anagram, her special focus on spatial/temporal manipulation had not diminished, but was supplemented with an additional admonition: the overall form of art films should be ritualistic.

In other words, although the film artist must take advantage of the medium’s special ability to creatively manipulate movement, these space-time manipulations must not be used to make a film form solely for the purpose of self-expression; rather, like the shaman or artist in “primitive society,” the film artist must engage in a more selfless goal of creating depersonalized art objects whose design and function, like that of ritual forms, is to assist others in comprehending their contemporary social conditions.45

While such prescriptive generalities ignore the overlapping possibilities of other forms, and while Deren herself never wrote extensively about the implications of ritual in film, the circular structure and trance like movements in Meshes render the female figure as a sort of “spiritual automaton,” moving in a measured, ritualistic way towards the destruction of the self. And Deren’s deep interest in continuity editing “holding its own in a volatile universe” would eventually bring her in the early 1950s “to call all her films ‘choreographies for camera,’ ‘chamber films,’ or ‘cine-poems,’ while emphasizing the medium’s ability to manipulate the temporal dimension above all else.”46 Deren writes that the cinema’s specific power comes from being

a time-form. . . more closely related to music and dance than it is to any of the spatial forms, [e.g., architecture] the plastic forms [e.g, sculpture, but here also, painting or photography that represents of solid objects with three-dimensional effects]. Now it’s been thought that because you see it on a two dimensional surface which is approximately the size and shape of the canvas. . . that it is somehow in the area of the plastic arts. This is not true, because it is not the way anything is at a given moment that is important in film, it is what it is doing, how it is becoming; in other words, it is the composition over time, rather than within space, which is important.47

Deren is arguing here that film is essentially a time art, experienced like music or dance each time as a recreation, as it becomes, rather than a series of dimensional, pictorial compositions within a frame.

Conclusion

The nontraditional narratives of Andrei Tarkovsky and the experimental work of Maya Deren use internal rhythm and editing in different ways to open up the “inner sphere” of human life. Compared simply as examples of cutting, Mirror and Meshes of the Afternoon are more alike than they seem at first glance. Tarkovsky and Deren share at least two common cutting techniques: cuts that disguise the shot change by cutting within a camera move that is matched on the outgoing and incoming shot and cuts that “pop” objects and people out of frame. But Tarkovsky would likely object to some of Deren’s overt uses of the stop-motion substitution technique, including the locked down camera sequence that “animates” her up and down the stairs. He would also oppose some of the unconcealed editing techniques where Deren aims for a predetermined effect, like the stride sequence in Meshes that match cuts the female figure wearing reflective glasses stepping into five different spaces to visualize the internal journey towards suicide. As Tarkovsky once wrote, “Never try to convey your idea to the audience – it is a thankless and senseless task. Show them life, and they’ll find within themselves the means to assess and appreciate it.”48

Compared simply as examples of internal rhythm, both Tarkovsky and Deren carefully control character movement and use slow motion as a way to mimic the fluctuating rhythms of duration, or time as we experience it. Both use camera movement to follow action in lieu of cutting, repeated movement motifs and the dream like effect created by slow motion cinematography. With its low tech, poetic approach, multiple imagery and ties to dance and ritual, Meshes is closer to the screen magic of Georges Méliès, trying to persuade us that the dream/ritual before our eyes is real, while Tarkovsky’s Mirror works to continually blur the distinction between reality and non-reality through a restrained editing style that avoids analytical cutting.

Notice that many of the issues we examine in this chapter lead us to the next chapter, since they fall under the broad concept of pacing which Karen Pearlman defines as “a felt experience of movement created by the rates and amounts of movement in a single shot and by the rates and amounts of movement across the series of edited shots. . . Pacing is the manipulation of pace for the purpose of shaping the spectators’ sensations of fast and slow. The word “pacing,” like the word “timing,” is used to refer to three distinct operations: the rate of cutting, the rate of concentration of movement or change in shots and sequences, and the rate of movement or events over the course of the whole film.”49 For Tarkovsky, the singular focus he gives to “the rate of concentration of movement” within a shot becomes the point of convergence in an editing process where shots join up naturally according to the intrinsic movement patterns they contain.

For Deren, the focus on pace is less central because it is only part of a choreography before the camera that will be augmented with low tech special effects, with screen magic using the stop-motion substitution effect, and with continuity editing that energizes and destabilizes space to generate extraordinary movement. Cinematic pace, for these two filmmakers, is one way to unlock the inner reality of human life. But as we will see in the next chapter, it is also a primary area for emotional and narrative control in the editing of more traditional narratives.

Notes

1 Andrey Tarkovsky and Kitty Hunter-Blair, Sculpting in time: reflections on the cinema (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986), 68.

2 Thorsten Botz-Bornstein, Films and dreams: Tarkovsky, Bergman, Sokurov, Kubrick, and Wong Karwai (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, Rowman & Littlefield, 2008), xi.

3 Ibid., 15.

4 Maya Deren, “Poetry and Film: A Symposium,” in Film Culture Reader, edited by P. Adams Sitney (New York: Praeger, 1970), 171.

5 Moira Sullivan, “Maya Deren’s Ethnographic Representation of Ritual and Myth in Haiti,” in Bill Nichols and Maya Deren, Maya Deren and the American avant-garde (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001), 208.

6 Lucy Fischer, “The Eye for Magic: Maya and Méliès,” in Bill Nichols and Maya Deren, Maya Deren and the American avant-garde (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001), 202.

7 Thorsten Botz-Bornstein, Films and dreams: Tarkovsky, Bergman, Sokurov, Kubrick, and Wong KarWai (Lanham MD: Lexington Books, 2008), 23.

8 Ibid., 113 and 119.

9 Ibid., 20.

10 Ibid., 70.

11 Ibid., 66 and 68.

12 Ibid., 114.

13 Donato Totaro, “Time and the Film Aesthetics of Andrei Tarkovsky,” Canadian Journal of Film Studies 2(2) (1992): 23.

14 Andrey Tarkovsky and Kitty Hunter-Blair, Sculpting in time: reflections on the cinema (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986), 116–117.

15 Ibid., 63.

16 Ibid., 63.

17 Ibid., 57.

18 Ibid., 57.

19 Donato Totaro, “Time and the Film Aesthetics of Andrei Tarkovsky,” Canadian Journal of Film Studies 2(2) (1992): 26, my emphasis.

20 Ibid., 22.

21 Ibid., 25.

22 The clip, “The Mirror: Time Pressure and Découpage In Oneiric Cinema. Fire, Leaves, Shower” is on Critical Commons at http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/m_friers/clips/the-mirror-time-pressure-and-decoupage-in-oneric.

23 Vlada Petric, “Tarkovsky’s Dream Imagery,” Film Quarterly 43(2) (1989): 32, doi:10.2307/1212806.

24 Andrey Tarkovsky and Kitty Hunter-Blair, Sculpting in time: reflections on the cinema (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986), 133.

25 The clip, “Mirror: Time pressure and Découpage in Oneiric Cinema. Earrings, Cockerel, Bed.” is on Critical Commons at http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/m_friers/clips/mirror-time-pressure-and-decoupagein-oneric.

26 Andrey Tarkovsky and Kitty Hunter-Blair, Sculpting in time: reflections on the cinema (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986),133.

27 Ibid., 63. The Russian title of Tarkovsky’s book, “Запечатлённое время”, is literally translated as “imprinted” or “depicted” time.

28 Maya Deren in Renata Jackson, The modernist poetics and experimental film practice of Maya Deren (Lewiston, NY: E. Mellen Press, 2002), 36.

29 Ibid., 37.

30 Richard Allen in ibid., 36.

31 Annette Michelson, “Poetics and Savage Thought: About Anagram,” in Bill Nichols and Maya Deren, Maya Deren and the American avant-garde (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001), 27.

32 Maya Deren, quoted in Douglas Gilbert, “Pioneer in New Film Art Makes Camera Part of Her Pictures,” New York World Telegram, April 17, 1946.

33 Maya Deren, “Amateur Versus Professional”, Film Culture 39 (1965): 45–46.

34 Renata Jackson, The modernist poetics and experimental film practice of Maya Deren (Lewiston, NY: E. Mellen Press, 2002), 202.

35 The clip, “Meshes of the Afternoon: Female Figure Dreams,” is on Critical Commons at http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/m_friers/clips/meshes-of-the-afternoon-female-figure-dreams/.

36 Maya Deren, An anagram of ideas on art, form and film, reprinted as end matter in Maya Deren and the American avant-garde, Bill Nichols and Maya Deren (Berkeley,CA: University of California Press, 2001), 18.

37 Ibid., 46.

38 The clip, “Meshes of the Afternoon: Female Figure Tumbles” is on Critical Commons at http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/m_friers/clips/meshes-of-the-afternoon-female-figure-tumbles/.

39 Ibid., 20.

40 The clip, “Meshes of the Afternoon: Female Figure ‘Pops’ In/Out and Multiplies,” is on Critical Commons at http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/m_friers/clips/meshes-of-the-afternoon-female-figure-pops-in-out.

41 Sarah Keller, Maya Deren: incomplete control (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 107.

42 Lucy Fischer, “The Eye for Magic: Maya and Méliès,” in Bill Nichols and Maya Deren, Maya Deren and the American avant-garde, (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001), 186.

43 “Untitled,” Maya Deren to James Card, April 19, 1955, in Essential Deren: collected writings on film, edited by Bruce R. McPherson (Kingston, NY: Docutext, 2005), 191. Note that Deren is not accurately describing the sequence: there are two shots near the ocean at the beginning rather than one, for a total of five matched shots.

44 Maya Deren, An anagram of ideas on art, form and film, reprinted as end matter in Maya Deren and the American avant-garde, Bill Nichols and Maya Deren (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001), 5, my emphasis.

45 Maya Deren in Renata Jackson, “The Modernist Poetics of Maya Deren,” in Bill Nichols and Maya Deren, Maya Deren and the American avant-garde (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001), 49.

46 Ibid., 51.

47 Ibid., 51.

48 Andrey Tarkovsky and Kitty Hunter-Blair, Sculpting in time: reflections on the cinema (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986),158.

49 Karen Pearlman, Cutting rhythms: shaping the film edit (New York: Focal, 2015), 47.