8 Rhythmic and Graphic Editing

An introductory text on film aesthetics argues that creative editing “offers the filmmaker four basic areas of choice and control:

- graphic relations between shot A and shot B

- rhythmic relations between shot A and shot B

- spatial relations between shot A and shot B

- temporal relations between shot A and shot B.”1

These four areas are universally available in the editing process, regardless of the genre. An experimental film might be constructed graphically, so that the edits are chosen solely on whether there is, say for example, the form of a circle present in each outgoing and incoming frame. Or that same film might be structured overall as a temporal reversal, so that the edits are chosen based solely on whether the incoming shot occurred before the outgoing shot. At the same time, these areas of control rarely exist “in a vacuum” as distinct categories: as editors, we might consider how a cut alters the spatial relationship of two shots, but that does not mean that other relationships – say, the graphic or purely pictorial parameters of the two cease to exist. Often, the editor merely is choosing which of these four to privilege at the cut or in the sequence. As we have seen, this phenomenon is what Eisenstein refers to as the emergence of the “dominant” in a sequence, and in classical Hollywood, the dominant was clarity in spatial and temporal relations between shots. As we saw in Chapter 3, that demand for clarity diminished in the 1960s: Walter Murch’s “Six Rules for the Ideal Cut” place those at the very bottom of his considerations for a cut after Emotion, Story, Rhythm and Eye-trace (or Eye-guiding) (See Chapter 3, p. 87.) Nevertheless, spatial and temporal concerns remain paramount in most editing decisions, a simple acknowledgement of the central aesthetic foundations of the medium. The noted art theorist Erwin Panofsky once described the unique potential of motion pictures as the ‘dynamization of space’ and the ‘spatialization of time’.2 In other words, inherent in the film medium is the ability to dynamically transport the viewer anywhere by a cut to another location, and the ability to depict the space before the camera over time (i.e., every shot necessarily reveals a sense of time inherent within it.)

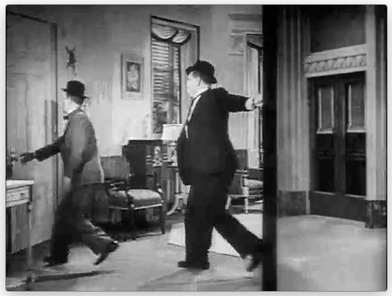

Because continuity editing is the dominant style of editing in narrative filmmaking, we tend to forget that it is a creative choice. We have seen the influence of continuity editing throughout this book in establishing what is known as the “zero point of cinematic style,” the “default mode” of editing. Continuity editing in the fiction film is a precise approach to mise-en-scène and cinematography that takes a series of discontinuous shots, and cloaks their discontinuity in a system of cutting that renders them “continuous.” Michael Betancourt acknowledges the long-standing maxim that editing simply mirrors the process of sequential photography that creates motion pictures in the first place:

The interruption of continuous motion that the edit inherently is results in a dramatic shift in space and perspective on the screen. Each image appears as an entire replacement of what was onscreen previously. The relationship between individual shots emerges within the minds of the audience: every shot is singular, the degree of its disruption simply being an exaggeration of the underlying sequential nature of images in a motion picture. Where normally only small differences appear, resulting in motion, with sufficiently large differences the changes become a change of shots.3

The “transparency” of classical film editing organizes shots into a larger structure that keeps the spatial/temporal/causal relationships clear throughout the course of a film. The general “invisibility” of continuity editing is supported by research finding that viewers have difficulty recalling the particulars of a film’s editing, and instead recall events in the film as one continuous progression.4 In many ways, this centrality of continuity editing has shaped our examination of all the theories examined here: it is the foundation, the normative “field” against which other “figures,” other approaches stand in relief.

The rules governing this style of editing are well codified, but more difficult to master than one might think: one need only watch amateur films to see the myriad ways in which the continuity system can be poorly executed. The system’s main rules are well known: the 180° rule for shooting coverage, the 30° rule for moving the camera between takes and cutting on action to facilitate smooth transitions from shot to shot. Continuity editing is frequently “analytical” meaning it smoothly cycles from establishing shots – providing the audience with the locale, time of day, relative position of the characters – through a series of closer shots that use continuing graphic, index or motion vectors to keep the audience spatially oriented. Continuity editing often returns to the establishing shot to “reestablish” the larger space as a character crosses or exits, uses cutaways to cover mismatches in action, and relies on transitions like dissolves and fades to signal temporal relations between shots and scenes, etc. But it is important to notice that while spatial and temporal concerns often prevail in continuity editing, rhythmic and graphic concerns remain, albeit as considerations that are generally less dominant. For example, regardless of the spatial and temporal relations between shot A and shot B, they will not cut seamlessly if the internal rhythm (what Tarkovsky calls “time pressure”) is mismatched in the two shots. Or if the basic graphic parameters of the two shots are mismatched – one of the shots is severely underexposed or mismatched in color balance – the cut cannot be seamless. (This, at the most basic level, is one meaning of the term “graphic match,” though the term “color correction” is more commonly used to describe how mismatched shots are “smoothed” against each other.) So when editing that makes temporal and spatial coherence the accepted goal is the “zero point” of style, it is not surprising that editing styles that move beyond that stand out as exceptional for their creativity and their expressivity. They also tend to be fertile ground for analysis, since they often expose assumptions about how the continuity editing system works at large. With that in mind, we will shift focus in this chapter from spatial and temporal questions to understanding the rhythmic and graphic possibilities of editing, primarily as these potentials are used in narrative filmmaking.

Rhythmic Relations in Editing

Pacing was identified early on in the history of motion pictures as an element that distinguishes a good silent picture from a bad one. D.W. Griffith once wrote,

[Pace] is a part of the pulse of life itself, and, being common to all human consciousness, its insistent beat has the curious power to seduce and sway the emotions, as the rhythmic tread of marching troops sways a suspended bridge. When the pace of a picture weds the pace of an audience, the results are astonishing.5

We identified three aspects of pace in the last chapter: “the rate of cutting, the rate of concentration of movement or change in shots and sequences, and the rate of movement or events over the course of the whole film.”6 In this chapter, we will focus on the first two, rather than the latter – analyzing the pace of entire feature films – and our purpose will be to understand some of the basic aspects of filmic rhythm and graphic relations in narrative films. Two caveats are worth noting here. The film theorist Jacques Aumont notes that the ear, not the eye, is our most accurate sense organ for determining rhythm. Unlike the perception of musical rhythm to which the ear is very precisely tuned, the eye is not adept at perceiving duration, so Aumont argues that rhythm in film is a combination of temporal and plastic rhythm, which are quite distinct.7 Plastic rhythm is characteristic of visual arts where repeated objects or shapes recur in a regular arrangement. We will examine some film scenes that foreground plastic rhythm below. And while the limitations of the visual system in determining duration may be significant, Karen Pearlman argues that we have intuitive access to rhythm:

I propose an editor learns where and when to cut to make a rhythm from two sources: one is the rhythms of the world that are experienced by an editor, and the other is the rhythms of the body that experiences them. . . The universe is rhythmic at a physical, material level. Seasons, tides, days, months, years and the movement of the stars are all examples of universal rhythms, and our survival depends on us oscillating with these rhythms and functioning as part of the rhythmic environment. Waking/sleeping, eating/digesting, working/resting and inhaling/exhaling are just some of living beings’ ways of following the rhythms of the world.8

Pearlman goes on to say that editors use their innate “kinesthetic empathy” or “corporeal imagination” to read the rhythm in rushes, and their own bodies to write filmic rhythm, in the same way that a musician’s body participates in the transmission of musical rhythm, “the rhythm of the material passes through the rhythms of the editor on the way to being formed.”9 “Reading” the rhythm of a shot we are intuitively deciphering internal rhythm; “writing” the rhythm of the edit by cutting, we are creating the external rhythm of a sequence, a scene, an entire film.

Early on, the French critic Léon Moussinac distinguished between diegetic elements that control rhythm and those created by the timing of the cuts, and the concept was expanded upon by the theorist Jean Mitry who first coined the terms internal rhythm and external rhythm.10 Mitry was a French film theorist and filmmaker who co-founded France’s first film society in 1925. A significant figure in the development of French cinema, Mitry directed and edited cutting edge films like Le Rideau Cramoisi (Astruc, 1953) and his own Pacific 231 in 1949. Mitry was highly influential as a film historian and film theorist, publishing his seminal The aesthetics and psychology of cinema, an extensive two-volume work in 1963 that systematically examined forms and structures that had been previously identified and debated by other theorists. Dudley Andrew points out that of all the classical film theorists only Eisenstein exceeds Mitry “in time and energy spent in editing rooms.”11 As a film practitioner, theorist, and historian, Mitry became a member of the inaugural faculty of L’Institut des hautes études cinématographiques, the national French film school when it opened in 1945 and later taught film studies at the University of Montreal.

Mitry endorses the notion that rhythm, or “perceived periodicity,” is tied to the two psychophysiological cadences of life – our heart-beat and our breathing – that establish:

- the concept of musical measure – the normal resting human heartbeat is 80 beats per minute

- the concept of “fast versus slow rhythm” – one faster or slower than normal resting heartbeat

- the rhythmic concepts of “tension, release, and rest” – the rhythmic pattern of breathing.12

Mitry says that only music can create pure rhythm, a system of strong and weak melodic or harmonic beats, while rhythm in literature, employing words, is less pure but attainable. For example, poetry creates a pattern of stresses on words within lines and measures of verse based on a preexisting pattern imposed by the form, as in this famous poem by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow:

Tell me not, in mournful numbers,

Life is but an empty dream!

For the soul is dead that slumbers,

And things are not what they seem.

Film rhythm, however, is more like rhythmic prose. Mitry argues film rhythm is linear, “It is the rhythm of narrative, whose continuous flow never repeats itself. . . it is the free and ‘continuous’ rhythm of rhythmic prose, never imposing a metric system on its cyclical forms but rather allowing its own requirements to dictate its terms of reference.”13 In contrast to the poetry above, consider the rhythm of prose in this line from the opening of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses, in which the character Gibreel is thrown from an exploding plane,

Gibreel, the tuneless soloist, had been cavorting in moonlight as he sang his impromptu gazal, swimming in air, butterfly-stroke, bunching himself into a ball, spreadeagling himself against the almost-infinity of the almost-dawn, adopting heraldic postures, rampant, couchant, pitting levity against gravity.14

In this instance, there is not an external, abstract form determining how the rhythm of the passage unfolds, but rather an unfolding rhythm continuously moving through the text. Given that film automatically captures time unfolding in a certain space, the existence of film rhythm seems indisputable: Mitry notes that there are film genres that “quite consciously involve the use of a specific rhythm. Clearly, a psychological film does not have the same rhythm as, say, an epic; it would be foolish to think otherwise.”15 Moreover, narrative filmic rhythm is “not produced, as in music, by rhythmic form but by events being followed through in the sequence. It is time experienced by characters objectively presented to us, not a sequence of time formulated and conditioned by pure rhythm.”16 The shots themselves, Theo Van Leeuwen notes, provide potential cutting points: “[F]ilm editors [do not] impose their rhythm on images, the images and sounds impose their rhythms on the editors, restrict them as to where and how the film can be cut.”17

Mitry points out that editors of narrative film are generally trying to determine the “life of the shot,” to use a familiar term. He says their aim is to create shot durations

proportional to the interest and signification of the content. It is this interest and it alone which can and must determine the shot-relationships, calculated in terms of the impression of duration which they produce and not by virtue of the metric length. . . [I]t is only a posteriori, i.e., at the editing-stage with the image on the editing-bench, that we can judge it at all accurately. . . In other words, film rhythm is never an abstract structure controlled by formal laws or principles applicable to all kinds of film but, on the contrary, a structure rigorously determined by the content.18

With Mitry in mind, we will use the term internal rhythm to mean “the rate of concentration of movement or change in a shot,” a term that encompasses character movement as well as any aspect of mise-en-scène that contributes to the perception of that change. Under that expansive term, we can also apply Herbert Zettl’s nomenclature describing timing and principal motions on the screen for greater precision. Describing event motion relative to the camera, Zettl uses the term primary motion that “always occurs in front of the camera, such as the movement of performers, cars, or a cat escaping a dog.”19 Zettl defines secondary motion as “camera motion, such as the pan, tilt, pedestal, boom, dolly, truck, and arc. Secondary motion includes the zoom, although only the lens elements, rather than the camera itself, move; aesthetically, we nevertheless perceive the zoom as camera induced motion.”20 Zettl argues that a director’s first concern should be with primary motion and camera placement that is best placed to capture that natural flow. Zettl points out that camera movement is independent from whatever action is happening in front of the camera and therefore, if used incorrectly, can bring attention to itself, rather than reinforce the intended effect of a sequence. “Nevertheless, secondary motion fulfills several important functions: to follow action, to reveal action, to reveal landscape, to relate events, and to induce action.”21

We will use Herbert Zettl’s term tertiary motion as the equivalent to external rhythm. External rhythm is sequence motion or dynamism, “the movement and the rhythm induced by shot changes by using a cut, dissolve, fade, wipe, or any other transition device to switch from one shot to shot.”22 Zettl acknowledges that external rhythm of a sequence is primarily determined by the simple rate of cutting within a sequence, how slowly or quickly the cuts follow one another. But what he wants us to recognize is that, at the most abstract level, the change from one vector field to another vector field as the shot changes has its own visual energy, an energy that can be different depending on whether the change is a cut, a dissolve, a wipe or a fade. Given this fact, “Transition devices and the length of shots determine the basic beat and contribute to the rhythm of the sequences and the overall pace of the show.”23 We will examine this idea further below.

Music: Internal or External Rhythm?

Finally, there is often some debate about how to classify sound elements under this scheme. Should music used to drive the cutting rhythm of a scene be classified as internal or an external element of rhythm? A simple resolution is to let the answer hinge on whether the sound element is diegetic or non-diegetic: that is, whether the sound source emanates (or appears to emanate) from the story space or whether it is “outside the story space.” For example, if a piano is being played in a scene, and it is part of establishing the rhythm of a scene, it is an element of internal rhythm, while a musical theme is added to a scene in postproduction is an element of external rhythm.

And here we should pause to note the obvious: the range of aesthetic factors driving the rhythm of a single shot change – much less of a sequence – is vast. For the editor – and for our analysis here – it is often difficult to isolate what the determining factor for a rhythmic cut is, as that factor is part of a complex of aesthetic factors in each shot. Or as Van Leeuwen describes the process from the editor’s perspective, “As there may be (and usually is) more than one profilmic rhythm, editors are faced with the problem of synchronizing the various profilmic rhythms – at least insofar as these have not been recorded simultaneously [i.e., if the shots are captured sequentially rather than with multiple cameras] and synchronously [i.e., if, for example, the dialog is looped], or been postsynchronized, as music often is. To do so, the editor chooses one of the profilmic rhythms, as an initiating rhythm and subordinates to this rhythm the other profilmic rhythms.”24 In short, when we analyze film rhythm here, we will simplify. But thinking through the myriad aesthetic forces that are at work within “filmic rhythm” will help you as an editor: you should emerge with some sense of the range of factors involved and with some tools to evaluate how rhythm is brought to bear in editing.

External Rhythm: Cutting Rhythm and the Decrease in Average Shot Length

We have already seen the leisurely external rhythm that results when a filmmaker relies on the long take championed by André Bazin in Chapter 6, and when Andrei Tarkovsky makes the “time pressure” of a shot the pivotal factor controlling overall rhythm in Chapter 7. On the other end of the “cutting spectrum,” we have seen how the new Hollywood style identified by Bordwell as intensified continuity results in faster cutting in Chapter 4. The average shot length for a Hollywood feature film was between:08 and:11 seconds in the 1930s, and five decades later, that number had dropped to between:05 and:08 seconds in the 1980s. Looking at a film like Almost Famous (Crowe, 2000) with an average shot length of just 3.9 seconds, David Bordwell argues that faster dialogue scenes must be responsible for the shorter shot length and that “Today’s editors tend to cut at every line, sometimes in the middle of a line, and they insert more reaction shots than we would find in movies from the classic studio years.”25

That may account for the accelerated cutting of the romantic comedy genre, but some of the acceleration in average shot lengths can also be attributed to covering the sheer progression of physical movement that unfolds in action movies. These films use extremely short shot durations to increase audience impact, while trying to maintain a level of narrative clarity, or clarity of action. When covering action, Dziga Vertov’s concept of documentary editing may be the most apt: “To edit: to wrest, through the camera, whatever is most typical, most useful from life; to organize the film pieces wrested from life into a meaningful rhythmic visual order, a meaningful visual phrase, an essence of ‘I see.’”26

In cutting an action scene, the question for the editor often is what will give the audience that essence of “I see”? In this regard, Karen Pearlman talks about three kinds of “movement” that unfold across any scene. First, there is physical movement in a scene – the editor focuses on actor movement, its arc, its acceleration, its velocity, its flux, etc. – by which the viewer experiences “kinesthetic empathy” (what Eisenstein termed the “motor imitative response”). Secondly, there is emotional movement in a scene where an editor might focus less on physical movement than on emphasizing the “dance of emotions” across a scene. (Pearlman admits that is a subtle difference, since emotion will often emerge from a movement pattern.) Finally, there is the movement of events across a scene, which includes things like the revelation of new information (significant or insignificant), the change of a direction in the pursuit of a goal, the reversal of a character’s objective, etc.27

To thrill audiences with the sheer kinesis that escapist films offer, action scenes staging a race, a fight, a rescue, a chase, etc., often focus on the first factor: physical movement. The editor works to enhance internal rhythm of the action covered in the source footage through fast paced, nonstop cutting. The dystopian action-thriller-chase Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller, 2015), a film that brought the director’s wife Margaret Sixel the Oscar for Best Editing in 2016, provides a wealth of examples of editing for physical action. Miller wanted the film to be comprehensible without dialogue, saying

Hitchcock had one of my favorite sayings about cinema: he said, “I want to make movies where they don’t have to read the subtitles in Japan.” And these chase films are like that. You want to be able to have clear syntax and for people to be able to read the film as if it were a silent movie.”28

Fury Road was extensively storyboarded to facilitate the roughly 2,700 cuts in the film. The cutting rhythm of the film is very fast. The Cinemetrics website tallied the first half hour of the film at 665 shots at an average shot length of 2.6, and a mean shot length of 1.7 seconds.29 John Searle, ASC, the cinematographer for the film, said that Miller, knowing the cutting would be fast, was adamant that the center of interest for every shot be placed in the center of the screen, so that

your eye won’t have to shift on an anamorphic frame, won’t have to shift to find the next subject when you’ve got 1.8 seconds of time to do that . . . All we would hear all the time was George saying “Put the cross hairs on her [Charlize Theron’s] nose” . . . The camera had to be in the center. He was very disciplined that way. Everything had to be in the center.30

Halfway through the film, Imperator Furiosa (Charlize Theron) negotiates with a biker gang, offering gasoline for safe passage through a canyon. See Critical Commons, “External Rhythm: Mad Max Fury Road, Quick Cuts.”31 The bikers believe her to be alone, but one of the women in Furiosa’s party, hiding in the gasoline tanker, begins to moan because she is in labor. Sensing that the standoff is about to go downhill, Furiosa leaps in to action to escape the canyon. This scene continues for sometime, but for the sake of brevity, we will look at the first:30 seconds of this sequence. It contains 27 shots, and the longest shot – at 54 frames or 2.25 seconds – is a wide shot of a single motorcyclist charging down the hill to attack the tanker. The shortest shots are both seven frames in length – a duration of roughly 1/3 of a second. One of these shots shows the motorcyclist sliding from frame left under the tanker and the other shows Furiosa looking down at her feet dangling through a hole in the tanker floor, after that same motorcyclist has grabbed her legs (though he’s not visible in this shot.) The average shot length here is thus 26 frames, or slightly over one second.

The first shot of action shows Furiosa diving over the trailer hitch, and the next shot continues that action as she rolls onto the ground on the other side of the trailer. The match is smooth, carried in part by the attack in the soundtrack of machine gun fire, which begins in the outgoing shot but syncs to her roll into the incoming shot with three bullet hits that kick up small clouds of dust. Centering in both shots is clear as she dives (outgoing) and particularly as the dust clouds erupt kinetically (incoming) precisely on the spot that she hits as she rolls. As she stops and turns to scramble aboard the tanker, which begins to roll out of the canyon, the action of the truck begins to dominate the primary motion vector: this is the first of a series of three shots moving left to right, that will be followed by a z-axis neutral close up of Max Rockatansky (Tom Hardy) driving the truck away. A high angle long shot from the other side of the canyon reverses the screen direction. From this point forward, with the tanker at the bottom of the canyon, and gunfire and motorcycles harassing “The War Rig” tanker from both sides, screen direction will shift quickly (yet appropriately) with an occasional neutral shot to soften the shifts. At durations of roughly:01 second, these reversals hardly “read” as screen direction reversals. And even at that extreme pace, the continuity cutting of the physical action is well matched and flows naturally throughout.

Once the motorcyclist has grabbed her legs, seen from under the truck, six neutral, z-axis shots follow, either from inside or from under the long tanker. The cutting here is quick and covers Furiosa’s struggle to kick free of the biker (Figure 8.1). The shot transitions from interior to exterior are very clean, because the primary motion vector is z-axis, and the action centered. The shots show Furiosa’s shock at being grabbed and then three kicks that break her free: one from inside the tanker, the next from the front undercarriage and the last from the rear undercarriage that show the motorcyclist sliding into the camera. This last moment of the biker rolling into the camera cuts seamlessly with the final shot – 22 frames long – that shows the fate of the motorcyclist, crushed under the armored wheels of the tanker. This explosive montage of struggle and death is the essence of action cutting: a clear string of six “cause-and-effect” shots in seven seconds that end “punctuated” with an easily readable moment of finality. While the pace of the cutting rhythm is blazing, Miller’s focus never leaves continuity of action.

And yet, fast cutting need not converge on the continuity of physical action. The climatic fight scene between Sugar Ray Robinson (Johnny Barnes) and Jake LaMotta (Robert DeNiro) in Raging Bull (Scorsese, 1980) uses quick cutting to synthesize the brutality of boxing with little regard for continuity. The scene was meticulously shot and edited using the collision montage techniques pioneered by Eisenstein. Longtime collaborator Thelma Schoonmaker won the Oscar for Best Editing on the film, a task that took six months rather than the seven weeks that was scheduled. Schoonmaker credits the preproduction of director Scorsese for her award: “I felt that my award was his because I know that I won it for the fight sequences, and the fight sequences are as brilliant as they are because of the way Marty thought them out. I helped him put it together, but it was not my editing skills that made the film look so good.”32 Todd Berliner argues that the film, shot by cinematographer Michael Chapman, was “grueling to plan, shoot, and edit, partly because it violates the logic of Hollywood’s filming and editing conventions which offer filmmakers a ready-made, time-tested blueprint for keeping spatial relations coherent, for comfortably orienting spectators, and for maintaining a consistent flow of narrative information. . . Raging Bull offers an aesthetically exciting alternative to Hollywood’s narrative efficiency and visual coherence.”33 Berliner points to Scorsese’s application of Eisenstein’s collision montage in some of the violent boxing scenes to underscore not just the physical movement of the scene, but Jake LaMotta’s subjective experience of that brutality. Continuity takes a back seat to the emotional/intellectual effect created by editing for visual/ kinetic conflict. Scorsese creates the experience of Jake’s whipping through collision editing, beyond what would be possible with conventional continuity that covers the scene’s physical movement.

Figure 8.1 Rapid cutting for physical movement in Mad Max: Fury Road (Miller, 2015). This dystopian chase film has an average shot length of 2.1 seconds. In order to make the rapid editing in the film comprehensible, Miller insisted that the primary action be consistently centered in the frame, as in this shot of Furiosa (Charlize Theron).

Source: Copyright 2015 Warner Bros. Pictures.

As LaMotta’s life is crumbling around him, he takes on Robinson on February 14, 1951, in a legendary battle that was later known as “The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre.” The scene opens in the final, savage 13th round, and after a minute, the two challengers face each other exhausted, with LaMotta on the ropes taunting Sugar Ray to continue. Internal and external rhythms slow as the scene cuts to Robinson, centered in the arena lights, breathing heavily. Scorsese uses a dolly zoom – a dolly back as the camera zooms in – coupled with a fade to near silence in the soundtrack to temporarily arrest the progression of “clock time,” to move the emotional tone of the moment into the uninterrupted flux of slowed, subjective time, a shift marked by a shot nearly:12 seconds in duration. The caesura continues in the reverse shot: a slow motion, push in of almost:09 seconds with LaMotta still on the ropes, standing almost dazed, as smoke swirls behind him. He appears almost Christ-like, seeming to accept the punishment that must come.

In the next shot –:02 seconds, 13 frames long – internal and external rhythm begin to accelerate. The soundtrack goes from eerie silence to a deafening roar, as Robinson, and the “sound space” around him advances to thrash LaMotta. Robinson moves forward to strike as the camera zooms in on his taut face, centering his predatory eyes, while his fists remain oddly quiet by his side. A punishing upper cut is shown in the next close up – technically, mismatched continuity – but a satisfying “energy release” that fulfills Sugar Ray’s forward, aggressive surge in the outgoing shot. From this point forward, Berliner notes, creating the subjective experience of LaMotta through collision montage dominates over continuity concerns, as mismatched action, jump cuts and nine violations of the 180° rule are obviated by the speed and intensity of colliding shots:

Scorsese packs into twenty-six seconds of screen time a sequence of thirty-five discordant shots that break fundamental rules of continuity editing in order to convey a subjective impression of La Motta’s [sic] brutal experience in the ring. As Robinson pummels La Motta, who is too tired even to defend himself, shots of the challenger’s punches combine in a barrage of inconsistent images. . . As the sequence progresses from shot to shot, the camera angles and framing do not follow customary editing patterns. Indeed, the combination of shots seems almost random.34

There are seldom slight changes in angle on the physical action; rather, the shots change dramatically from one side of LaMotta to the other side (Figure 8.2), from high to low angle placements, moving erratically to close ups of disparate material. See Critical Commons, “External Rhythm: Raging Bull, Quick Cuts, Collision Montage.”35 Berliner focuses on seven shots in the sequence to demonstrate just how far Scorsese goes to make the fight montage collide:

Shot one: Low-angle extreme close-up of the front of Robinson’s face. [22 frames]

Shot two: High-angle shot of La Motta’s head and his left arm on the ropes. [25 frames]

Shot three: Close-up tracking down from La Motta’s trunks to his bloody legs. [25 frames]

Shot four: Close-up of La Motta’s face being punched. [18 frames]

Shot five: Extreme low-angle shot of Robinson’s face. [9 frames]

Shot six: Extreme close-up of the left [sic] side of La Motta’s face, slightly low-angle, as a glove hits his head. [23 frames]

Shot seven: Bird’s-eye shot of Robinson’s head and face. [27 frames]36

Figure 8.2 Rapid cutting for the collision montage in Raging Bull (Scorsese, 1980). Collision montage – editing for visual/kinetic conflict – is used by Scorsese not primarily to show the physical movement in this scene, but Jake LaMotta’s (Robert DeNiro) subjective experience of that brutality.

Source: Copyright 1980 United Artists.

All of the conflict emerging from the juxtaposition of these close ups is augmented by irregular bursts of “flashbulbs from the press cameramen”, bright illumination that sometimes blows the exposure of the entire frame to a white flash. The flashing increases the internal rhythm of the scene through the irregular pulse it creates, while the cutting rhythm is very fast – the longest shot is 27 frames and the shortest is 9 frames, with an average shot length of just 21 frames. Berliner concludes that, unlike Eisenstein’s use of collision montage,37 which builds visual metaphors through the non-diegetic insert (i.e., Kerensky + peacock = Kerensky is vain), Raging Bull remains in the extant space of the boxing ring, using agitated editing to convey LaMotta’s inner experience of violence. This places the scene more in the company of non-traditional representations of the subjective experience of violence like the shower scene from Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) than Eisenstein’s efforts to “seize the spectator” with an edit that signifies a larger meaning.

Factors that Control Internal Rhythm

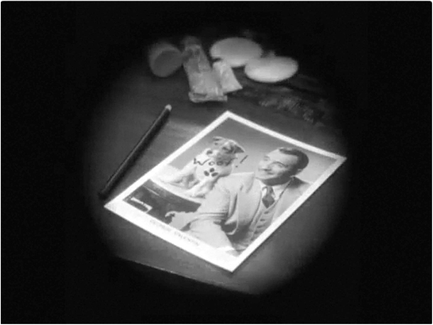

Figure 8.3 Internal rhythm: character movement in Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941). With little cutting, this two-minute scene shows the ability of Orson Welles to control its internal rhythm through character movement by regulating his anger in a meaningful trajectory.

Source: Copyright 1941 RKO Radio Pictures.

As we said earlier, internal rhythm is controlled by elements within the shot, mainly the movement of objects and people (primary motion). While any aspect of the mise-en-scène – not merely sets, props, costumes, but also camera or lens movement (secondary motion) and other elements like focal length, camera placement, and lighting – can make significant contributions to internal rhythm, we will begin by looking at primary motion, the movements of objects and people, movements that can be further classified by their tempo direction and pattern of the movement on the screen.38 To understand how primary motion controls internal rhythm, we can begin by looking at a scene from Citizen Kane that has very little cutting: the scene where Kane demolishes Susan’s bedroom after she leaves Xanadu. This scene demonstrates the importance of tempo. See Critical Commons, “Citizen Kane: Internal Rhythm, Movement of People and Objects and Composition (Repeated Forms).”39

Internal Rhythm: Tempo of the Action

Kane stands in the doorway of the Susan’s bedroom and, and as she leaves, he is clearly overcome with emotion, and turns back into the bedroom. The room is quiet. Kane walks stiffly to the bed and fumbles to place some of the clothes Susan has left behind into a suitcase. His anger is evident as he grapples with the latch. He turns abruptly and throws the suitcase (Figure 8.3). His blood begins to boil. The camera remains low and wide to show his full figure as he throws another suitcase and pulls the bedspread to the floor. The camera cuts closer as he proceeds to destroy the room in earnest, the sound level rising as he rips a bed canopy from the wall, and moves deeper into the room to smash a lamp with the sweep of one arm. From this point, Kane’s movements become more erratic, and the level and tempo of the soundtrack increase, growing denser and more chaotic. Welles holds his upper body in check, creating a contrast between the awkward, stiff movements of the elder Kane, and the expanding destruction around him. As Kane staggers through the wreckage of the room, tossing over a dresser and a chair, a match cut to a low angle shot brings the action close, and Kane looms in the foreground. He wrenches a small shelf of bric-a-brac from the wall and tosses it aside as his focus turns elsewhere. The pace is rising as he attacks another shelf, and the soundtrack is fierce with the clatter of books hitting the ground. He finds a bottle in his hand, and pauses to glance at it. He hurls it against the far wall, the singular crash marking a momentary pause. Kane lurches for a mirror and rips it from the wall. Fatigued, he stumbles against an overturned chair and circles back towards the camera, gasping for breath.

Now the pace is slowing, and the soundtrack returning to normal levels, as Kane comes close to the camera. He sends a final group of perfume bottles crashing to the ground, and pulls up short in a tight framing that shows only his hands and the bottom of his suit jacket. There is a moment of pause and dead silence. The camera tilts slightly as Kane carefully picks up a glass globe and moves towards the door, brushing an overturned nightstand out of his way. His outburst concluded, there is a welcome caesura: Kane pauses and looks down at the globe, and the film cuts to a close up of the snow filled globe seen at the beginning of the film and later on Susan’s dresser in the “love nest.” “Rosebud,” he whispers, and the camera tilts up to reveal the broken Kane staring into the middle distance, his eyes glistening with tears. To recap, the internal rhythm to this point has chaotic forward propulsion that steadily builds across most of the scene, broken only by moments of Kane staggering to the next section of the room he is intent on destroying. Once his anger is spent, however, the rapid deceleration in his pace is punctuated by only a few destructive bursts that tail off in to silence and this single word of dialogue.

From the point that Kane turns to destroy the room, the action plays out in four wide shots that run:46 seconds,:19 seconds;:07 seconds and:45 seconds. As an example of pacing controlled by character action, this two-minute scene shows the remarkable ability of Orson Welles to regulate the “time pressure” of his anger in a meaningful trajectory. The scene concludes as a slow dirge that brings Kane out of the bedroom into the halls of Xanadu. His household staff stand by silently, their inertia marking their emotional distance from him. Kane presses forward down the hall, condemned to loneliness, the figure of a “dead man walking.” As he passes an arched hall of mirrors, the stiff, “mechanical trance” of his broken walk is the primary motion controlling internal rhythm. But repeated in an infinity of mirrors, the multiplication of this action adds its own plastic rhythm to conclude the scene. We will address other examples of plastic or compositional rhythm later in this chapter (see p. 290 below).

Internal Rhythm: Pattern of Movement and Lens Usage

Another key parameter for the control of internal rhythm is the pattern of movement within the frame. As we noted in Chapter 1, Arnheim described the motion picture as something between two-dimensional and three-dimensional, a medium which has “simultaneously the effect of an actual happening and of a picture.”40 When we look at “pattern of movement” as a part of a scene’s internal rhythm, we try to focus on how action and composition produce the “pictureness” or two-dimensional composition in a frame. Again, this is “plastic rhythm” resulting “from the organization of the frame’s surface content or its division in terms of lighting intensities, colors, or any other compositional factors. Such plasticity in the image follows from classic issues dealt with by such theorists of twentieth-century painting as Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky.”41 Like any complex phenomenon, “pattern of movement” in a film is hard to describe in words, not only because words like “flowing” or “balanced” or “staggered” or “chaotic” are broad terms, but also because in every shot, other factors interact to facilitate the pattern, notably lens usage, camera placement, lighting and color. Concrete examples here will illustrate how a pattern of movement influences internal rhythm, and the comparison of two scenes of men marching from the work of Stanley Kubrick will be our starting point.

See Critical Commons, “Internal Rhythm: Barry Lyndon, Pattern of Movement, Marching Comparison.”42

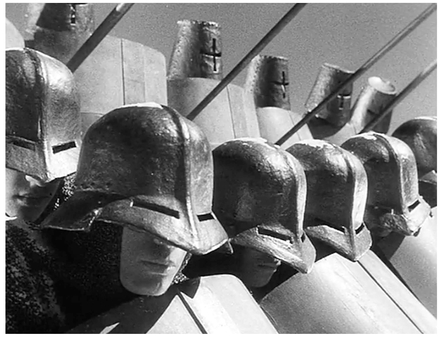

In Barry Lyndon (Kubrick, 1975), one of the early scenes of the film shows a British army company led by John Quin (Leonard Rossiter) parading for the people of Bradytown in Ireland, as they prepare for war against French invaders. The scene opens with a classically composed wide shot of the company standing to attention in a field with no real sense of the surrounding space: in this instance, the men are arranged as a long, flat, red “graphic area” that fills the lower third of the frame. They face head on to the camera as two flags flap in the breeze, the composition flattened by the use of a long lens. As Captain Quin orders the company to forward march, the fife and drum corps begins to play “The British Grenadiers.” The lines of men are straight and their bayonetted muskets are all properly aligned, and their marching is precisely coordinated. They all start off in unison on their left foot, standard procedure that is initiated after the preparatory command “Company . . . ” and the command of execution, “Forward march!”

A slow zoom out –:20 seconds of a:47 second long shot – accompanies their march forward revealing the assembled townspeople in the foreground, and fields in the middle ground and a mountain in the distance. The soldiers are now considerably smaller in the frame as the camera zooms out, but they continue as a single unit, marching towards the camera in tight formation. With aerial perspective from the haze in the valley flattening the composition, the scene ends as a stable, balanced, symmetrical arrangement, the internal rhythm of the marching slowed since the formation occupies a smaller portion of the frame. In this shot, the zoom is useful as a device to literally “open the scene” and reveal the townspeople present. Zoom outs are a common aesthetic device in Barry Lyndon: 36 appear in the film, including six of the first eleven scenes in the film that each begin with a long zoom out.43 In addition, this is the first of a number of marching scenes that will appear in the film. The stable primary motion created by the march itself, augmented by the slow zoom out, and the balanced composition that ends the shot, gives a feeling of quaint patriotism, particularly in comparison to some of the later marching scenes where the soldiers calmly advance into withering, deadly fire from the enemy. Overall, the opening rhythm here is lively and stable.

Later in the scene, the company marches right to left across the screen in perfect formation, with the camera trailing behind them in a slight pan to the right. The closer placement and horizontal movement in the frame is more dynamic, but controlled and even, still following the cadence of the original shot. Two closer shots introduce Quin, and show Barry (Ryan O’Neal) looking on enviously with his cousin Nora (Gay Hamilton). The scene closes as it opened, with a return to the opening wide shot as the soldiers raise their muskets and fire a salute, startling the crowd and their horses. The regularity and bright energy of this marching scene will stand in contrast to ones that come later.

Thinking that he has killed Captain Quin in a duel, Barry escapes to join the army. He fights in battle, and ultimately deserts the British army by stealing a courier’s uniform and horse. Barry is exposed as a fraud and forced to join the Prussian army. Later in the film, a four-shot sequence shows the dissipation of the Prussian army at the end of the Seven Years’ War, and links that decline to the moral fall of the protagonist. The internal rhythm established in this scene is more rambling and loose, and the lens usage here plays a more important role in flattening the movements of the army into a visual pattern covering the screen (Figure 8.4).

The sequence uses foot soldiers that are staged marching carelessly towards the camera in three telephoto shots and one wide-angle shot. In the first shot, Barry is centered in an uncoordinated platoon of soldiers who loosely march towards the camera. The action is staged with Barry centered in the bottom third of the frame, the platoon walking roughly in time with the march of a fife and drum corps that accompanies the scene. The soldiers move down a slightly sloped field, and the telephoto lens used flattens the perspective of the shot so that the army is spread across the frame, with a few rows in the back in slightly soft focus. The lines are ragged and irregular. The soldiers do not coordinate the alternate hand forward as they step. Their muskets are held at a variety of angles, particularly Barry’s which is sloping towards his right shoulder, making it one of the more visibly “out of formation.”

Figure 8.4 Internal rhythm: pattern of movement and lens usage in Barry Lyndon (1975). A shot’s “pattern of movement” can control internal rhythm by arranging the two-dimensional composition in a frame. The pattern established in this scene is rambling and loose. The telephoto lens usage here plays an important role in flattening the movements of the army into a visual pattern covering the screen.

Source: Copyright 1975 Warner Bros.

The fife and drum song continues, and in a second wide shot, the musicians lead the platoon as it snakes down a hillside. Here, their movement is no longer directly along the z-axis towards the camera, but rather, off axis, so that the platoon is seen almost like a river of men flowing down the hill, with a camera placed “on the river bank”. Given that the shot is wide, the platoon’s movements are no longer “spread” across the screen. Consequently, the effect is as if they are moving in a formation that is tighter than the previous shot.

The third shot returns to a long lens with the action directly towards the camera, but this time the framing is wider than the first shot. The wider scope reveals roughly 10 rows of soldiers marching, their lines extending deep towards the horizon. Here, two flapping flags and an officer who leads on his horse breaks the offhand formation of the lines while overlapping rows of soldiers fill the spaces in between. With the flattened perspective of the lens, the mass of men fills the frame and seems to oscillate forward at a pace that loosely follows the drum corps. The scene closes with a telephoto shot that singles out Barry using selective focus, as the ragged procession continues to shamble towards the camera. Here again, the telephoto lens slows the primary motion of the shot since its inherent aesthetic retards z-axis motion towards (or away from) the camera. The disorder of this scene visually encapsulates how the war has worn down and commandeered the lives of the impoverished Prussian soldiers, particularly in comparison to the polished, but untested, vigor of Quin’s regiment seen earlier. Pattern of movement and internal rhythm make the comparison clear.

Another exceptional example of the telephoto lens effect on internal rhythm is found in an airport scene in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (Alfredson, 2011). See Critical Commons, “Internal Rhythm: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, Telephoto Lens Slows Motion Towards the Camera.”44 A retired British intelligence officer George Smiley (Gary Oldman) is trying to get Toby Esterhase (David Dencik) to reveal the location of a safe house where Soviet spies are meeting with a British agent. Smiley threatens to send Esterhase back to Hungary, where he would be treated as a traitor. At the airport, Esterhase and Smiley are talking on the tarmac, when suddenly in the distance a plane drops into the frame and lands on the runway behind them. The plane represents an immediate threat to Esterhase, and as the plane taxies forward, he tries to explain his way out of being sent back.

The approach of the plane is acutely slowed and the space of the runway “flattened” so much so that it almost appears as if they are standing in front of a digital projection of a plane. Esterhase is unnerved by the plane’s approach, whose arrested movement seems ominous and dream-like (Figure 8.5). This visual “spell” is broken at the end of the shot as the plane finally pulls close enough to come into focus, turns slightly and brakes while killing its engines. Smiley’s dialogue punctuates that moment in rhythm by finishing Esterhase’s thought: “Operation Witchcraft. Yes, I know,” and the shot ends with a cut to the next shot. Esterhase pleads for his freedom, but ultimately gives up the address of the safe house. The scene was reportedly shot with an extremely long, 2000mm lens.

One final example will illustrate how patterns of movement and lens usage can work together to control internal rhythm. In Aguirre: Wrath of God (Herzog, 1972), the Spanish soldier Lope de Aguirre (Klaus Kinski) leads a group of conquistadors down the Amazon River in a mad search for the legendary city of gold, El Dorado. After enduring months of treacherous slogging through the jungle with European armor, guns and canons wholly unfit for the jungle, the decimated party builds a raft to float down the Amazon. By the end of the film, all of the party except Aguirre has died from starvation, disease or from the arrows that constantly strike them from unseen natives on the banks. See Critical Commons, “Internal Rhythm: Aguirre, Character Movement, Wide Angle Lens.”45

The sequence opens as Aguirre cradles his daughter, killed by an arrow. He surveys what is left of the raft, now overrun by monkeys. In a voice over peppered throughout the scene, Aguirre’s metal illness and megalomania is fully revealed. His raft is slowly sinking, but he is thinking grandiose thoughts that he narrates intermittently across the entire scene:

When we reach the sea, we’ll build a bigger ship, and sail north in it to take Trinidad from the Spanish crown. Then we’ll sail on and take Mexico away from Cortés. What great treachery that will be! Then we shall control all of New Spain and will produce history as others produce plays. I, the Wrath of God, will marry my own daughter, and with her I’ll found the purest dynasty the earth has ever seen.

Figure 8.5 Internal rhythm: telephoto lens in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (Alfredson, 2011). In this shot, the internal rhythm of the primary motion – the plane approaching down the runway – is slowed by an extremely long telephoto lens.

Source: Copyright 2011 Focus Features.

Throughout, the wide angle lens is used for practical reasons – it is easier to maintain focus and framing when hand-holding a camera – as well as aesthetic ones – its great depth of field and distorted perspective allow Herzog to push in unnervingly close to Kinski, whose unstable stance and piercing gaze carry the authentic look of insanity (Figure 8.6).

A number of shots in this sequence are particularly telling of Aguirre’s lunacy. As he stands defiant in the center of the raft, a handheld, wide angle shot pushes so close to his face that the proxemics of the shot become intimate, uncomfortably close, and time seems to slow as the shot holds for:15 seconds. Proxemics in film refers to the effects of spatial relations between camera and subject on the kinetic and emotional impact of a scene.

As the camera sways slightly with the rocking of the raft, Kinski stands upright and intractable, the intensity of his madness written in his eyes. (Apropos Murch’s blink theory, notice that Kinski does not blink in this shot.) Here, character movement is absolutely minimal, so the camera’s instability and wide lens’ power to slightly distort his face and maintain close focus amplify what little primary motion is present to an acute level: there is an energy present in Aguirre that projects into the space. Interviewed once about The Great Ecstasy of Woodcarver Steiner (Herzog, 1974) Herzog commented on his use of the handheld camera versus the tripod:

I want the camera to breathe and be physically present . . . A tripod always corresponds to an inhuman position, it’s fixed . . . So the camera should always be steady as if it were on a tripod, and yet the cameraman actually moves closer to the subject . . . It’s another kind of internal involvement, another form of access.46

A second shot that exemplifies internal rhythm well is a: 53-second wide shot in which Aguirre walks in his armor, helmet, sword and leather boots across the sinking raft. The footing is clearly treacherous, but Aguirre’s gait has the air of a mad man, staggering in an angular walk and kneeling to come face to face with a group of monkeys cowering on the corner of the raft. In stark contrast to his grandiose scheme to conquer New Spain, he is literally “lording it over the monkeys.” The pattern of chaos created as the monkeys scurry across the raft, leaping in fear from log to log and scrambling over one of the dead crewmembers suggests that maybe even they understand that Aguirre is unhinged. At the end of this shot there is a jump cut to Aguirre staggering forward to catch his balance against a canon.

Figure 8.6 Internal rhythm: wide angle lens in Aguirre: Wrath of God (Herzog, 1972). With character movement minimal in this shot, the wide lens’ power to slightly distort Aguirre’s (Klaus Kinski) face, coupled with the camera’s instability, amplify what little primary motion is present to an acute level: the intensity of the conquistador’s madness is palpable.

Source: Copyright 1972 Werner Herzog Filmproduktion.

That cut is part of a strategy of hard cutting across the scene so that the external rhythm reinforces the edgy internal rhythm that is unfolding across the raft. Shot in cinéma vérité style, the coverage lends itself to elliptical cutting, and jump cuts propel Aguirre forward in the scene, while cuts to the monkeys roving across the raft serve as the “objective correlative:” they are forcible images of his deterioration. If we consider only the progression of Aguirre’s placement in scene, the elliptical cutting moves him from cradling his daughter to a close up in the center of the raft looking over his right shoulder, to a circling close shot looking over his left shoulder, to the long shot just described where he staggers along the edge of the raft, to the canon, to the final tracking shot over his shoulder where he corners a group of monkeys. Spatially, Aguirre ranges erratically across the raft, via a weaving camera that follows him and via the jump cuts that render his movements even more volatile.

In the last shot particularly, the wide-angle lens brings the viewer into Aguirre’s madness by dynamically spatializing his walk. As he moves past a flag, the camera crosses very close on the other side, sweeping it across the foreground and energizing it with distorted perspective. As he moves under a wooden tent pole, the camera ducks under with him, as if the viewer is prowling behind. At the close of this careening shot, the camera pushes in for a climatic moment: Aguirre grips a small monkey who writhes and screams in fear. He declares aloud, “I am the Wrath of God. Who else is with me?” Then, in an inspired moment where Kinski truly inhabits his character, he casually tosses the monkey into the river. Herzog says of the film’s ending, “it isn’t so much a happy ending as an exact one, a suitable ending – there is no deeper meaning in it. As for the monkeys on the raft at the end of Aguirre, that was the only way to end the film, the only way to get an appropriate ending.”47

Internal Rhythm: Camera Placement

Beyond character movement and lens usage, the placement and movement of the camera itself can contribute to the internal rhythm of a shot. Again, the range of potential choices here is vast, but a few examples can illustrate the underlying rhythmic principles an editor must be aware of in constructing a scene. Camera placements that are at the eye level of the actor are considered normative, and elevations above or below this placement frequently connote power or lack of it. As Herbert Zettl notes,

Physical elevation has strong psychological implications. It immediately distinguishes between inferior and superior, leader and follower, and those who have power and authority and those who do not. Phrases like the order came from above, moving up in the world, looking up to and down on . . . all are manifestations of [this] strong association.48

Moreover, traditional screen aesthetic holds that camera elevation has an effect on internal rhythm: a high angle shot tends to slow or diminish internal rhythm, while a low angle shot tends to accentuate internal rhythm. See Critical Commons, “Internal Rhythm: Citizen Kane, Low Angle Increases Internal Rhythm.”49

Low angle camera placements are used throughout Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941), and the film was notable for showing the ceilings of its set – made from stretched muslin – a rarity for a Hollywood studio production of its era. In the film, the political boss Jim Gettys (Ray Collins) uses Kane’s affair with Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore) to destroy Kane’s chance to be elected governor and end corruption in the state. In the morning following Kane’s loss, Jedediah Leland (Joseph Cotten) comes to the campaign headquarters drunk and angry that Kane has failed his family, his friends and electorate of the state. Character movement in the scene is minimal, and the pacing of the dialogue is even, save for those moments when Leland presses Kane to let him go to work on the newspaper Chicago, the first crack in their solid friendship. Neither actor is heroic in this scene, so the choice of the low angle, wide shot to “elevate” them, to “look up to them” is not a thematic concern.

What does emerge from the low camera placement is a kind of smoldering anger, a tension that builds as they circle each other. Leland dresses Kane down for his failure to really love anyone, but Kane is unwilling to acknowledge and accept his failures. The low placement helps carry the threat implied in their body language and dialogue that this encounter might spill over into hostility and even violence. The scene begins to pivot when Jedediah’s criticism of Kane becomes more pointed (Figure 8.7). He finally says, “You don’t care about anything except you.” Now Kane retreats toward a nearby table, and the low placement reveals a reminder of his failure – a “Kane for Governor” banner on a ceiling beam – and renders his crossing of the room dynamic and charged with emotion in a way that an eye level placement could not. The staging, the use of ceilings and the low placement playing against the traditional “elevation” of the character energize Kane’s movements so that they read more like “caged animal” than “hero.”

Jedediah continues his attack, and the shot changes to another low angle wide shot as he walks forward, marching into Kane’s personal space to ask for a transfer to Chicago. Now both men loom in the foreground as they struggle over the issue, and as it becomes clear that Jedediah will resign if he’s not granted a transfer, Kane relents and says he can go. But as Kane pours himself a drink, he tries one more time to convince Jed to stay, only to be interrupted, “Will Saturday after next be alright [for me to leave]?” The low placement continues to energize the internal rhythm of their dialogue and their movements as the stare each other down, the hostility and disappointment between them palpable. Kane closes the scene with a toast: “To love on my terms, that’s the only terms anybody ever knows – his own.” Throughout, the visual dynamism of the low placement has enlivened the emotionally charged exchange between the two old friends.

Figure 8.7 Internal rhythm: low angle placement in Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941). With character movement minimal, the low placement in this scene helps to energize the internal rhythm of the dialogue and movements of Kane (Orson Welles) and Jedediah Leland (Joseph Cotten) as they stare each other down.

Source: Copyright 1941 RKO Radio Pictures.

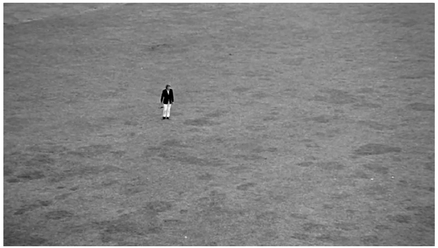

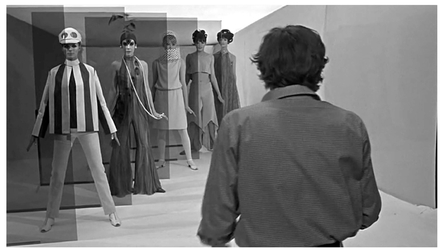

An altogether different use of camera placement crowns the ending of the 1960s classic film, Blowup (Antonioni, 1966). Here, the central character Thomas (David Hemmings), a swinging London fashion photographer, returns to a park where he believes he has photographed a murder. Antonioni’s film expresses deep reservations about a “mod” world in which the photographer is so distracted by the surfaces of the world he inhabits that he lacks the moral gumption to actually deal with what he believes to be the death of another human being. At the same time, Antonioni asks the audience to address questions about whether what the photographer sees may or may not be true. Those two ideas dovetail effortlessly in the closing sequence of the film. See Critical Commons, “Internal Rhythm: Blowup, High Angle Camera Placement Decreases Internal Rhythm.”50

The photographer wakes up at sunrise in a house where he partied all night long, and returns to the park alone, having failed to convince anyone of what he thinks he has seen. He finds nothing to prove there was a murder, and is leaving the park when a troupe of anarchic mimes arrive in the park and begin to “play tennis” in pantomime. The photographer looks on as the “match” progresses, and is slowly drawn into the “game,” as one of the mimes appears to hit the tennis ball over the fence and out of the court. The camera tracks the illusory “ball” as it rolls to a stop, and the female tennis mime gestures for the photographer for help retrieving it. As the troupe looks on silently, he trots over to retrieve the “ball.” Setting his camera on the grass, he “hefts” the imaginary ball and runs towards camera, “heaving” it back onto the court. Here, the camera holds him in a medium close-up for:36 seconds, while the sounds of a tennis ball being volleyed back and forth are slowly sneaked underneath the shot. In a remarkable moment, the photographer’s eyes begin to follow the “ball” until he pauses, and seems to be thinking back over what has transpired.

The film then cuts to an extremely high angle wide shot (Figure 8.8), a framing that not only trivializes the main character and all he represents, but that also reduces his movements to a slow crawl as he walks idly back to pick up his camera. He then walks to the center of the frame and pauses, swinging his camera slightly by his side. With this placement, the film’s momentum gradually winds down. The high angle shot brings down the curtain on his moment of contemplation and serves as a visual marker that slows his actions. An instant later, Antonioni dissolves to the same framing without the photographer, essentially erasing him from the film in a moment of overt directorial control, and triggering the appearance of the end credits. Roger Ebert summarizes the ending of the film this way:

What remains is a hypnotic conjuring act, in which a character is awakened briefly from a deep sleep of bored alienation and then drifts away again. This is the arc of the film. Not “Swinging London.” Not existential mystery. Not the parallels between what Hemmings does with his photos and what Antonioni does with Hemmings. But simply the observations that we are happy when we are doing what we do well, and unhappy seeking pleasure elsewhere.51

Figure 8.8 Internal rhythm: high angle placement in Blowup (Antonioni, 1966). In the last moments of the film, Antonioni cuts to an extremely high angle wide shot of the main character Thomas (David Hemmings), a vapid fashion photographer of the mod scene in London. The framing reduces his movements to a slow crawl as the film’s momentum winds down.

A similar effect where the high angle shot slows the primary motion of many actors can be seen throughout the climactic battle scene in Spartacus (Kubrick, 1960), a Roman epic that Kubrick was brought on to direct after Anthony Mann was fired early in the production. The film was shot in an ultra-widescreen Super 70 Technirama format, a horizontal 35mm format for blow up to 70mm that is similar to VistaVision. The wide, high definition image was used to capture large panoramic scenes, including one battle scene with 8,000 Spanish soldiers playing the Roman army. In the scene, the opposing forces occupy opposite sides of a valley. Spartacus (Kirk Douglas) and his rag tag army of rebellious gladiators face a much larger force of disciplined Roman legions lead by Crassus (Laurence Olivier). Spartacus’ army holds the high ground while the legions organize their formations in the valley, preparing for the assault. See Critical Commons, “Internal Rhythm: Spartacus, High Angle Camera Placement Decreases Internal Rhythm.”52

Shots of the legions marching into position are captured in extreme wide shots from a high angle position, while the long shots showing the concerned reactions of the rows of soldiers in each army are much closer, and often below eye level. The sheer magnitude of the Roman legions is impressive, and once they move to mid-valley and pause, the camera’s point of view remains with the gladiators as the legions approach. Pre-battle maneuvering was a common Roman legion tactic as commanders prepared for an impending clash. The tempo of the legion’s choreographed formations moving into position – shot from an aloof angle that scales their forward march into sweeping formations – is slowed by the high camera placement, allowing the patterns to play out in very long, leisurely takes. As the tension of the impending battle builds, a line of Roman soldiers moves into a forward line, while the legions in the rear close ranks into a tighter formation. A high angle side shot brings the two armies to a face off from opposite sides of the frame, while the sound of thousands of shields being raised in unison creates a thunderous noise. As the legions begin their charge, Spartacus, in a series of closer shots, orders flaming logs rolled down the hills to halt the Roman attack (Figure 8.9).

But Kubrick stays with the high angle wide shot as the battle begins to turn, the blazing logs breaking the Roman ranks as the gladiators’ counterattack commences. For the opening of this battle, the high angle wide shot is a choice that reveals the scale and pattern of the maneuvering legions, a choice that will be fully evident in the 70mm widescreen distribution for which it is intended. Moreover, the high angle shot slows the pace of the ponderous pre-battle, providing contrast to the aggressive, close combat to follow. Kubrick will move the camera closer and lower as the battle plays out, but even here will often stay above the fray so that the sheer scale of the production is written across the big screen.

Figure 8.9 Internal rhythm: high angle placement in Spartacus (Kubrick, 1960). In Spartacus, the tempo of the Roman legion’s formations moving into position is slowed by the high camera placement, allowing the patterns to play out in very long takes, even in a series of closer shots where flaming logs are rolled down the hills to halt the Roman attack.

Source: Copyright 1960 Universal International.

Internal Rhythm: Scope of the Shot

Classic screen theory holds that the scope of the shot can affect the perceived duration of a shot. Jean Mitry acknowledges that hard-and-fast rules about the relationship between the scope of a shot and perceived duration are suspect because of the large possible number of variables involved. Nonetheless, he claims that, in general, “the more dynamic the content and the wider the framing, the shorter the shot appears; the more static the content and narrower the framing, the longer the shot appears.”53 If we first consider “movement energy” in the frame, it seems obvious that – given two shots of the same scale – shot A of a moving scene or high dynamism action will appear shorter than shot B of a static scene or low dynamism action. Further, if any given action C is framed as a wide shot, if feels shorter (duration) than if C is framed in close up, since the viewer often has the need to visually scan the frame in a long shot. As the viewer interacts with information distributed across the frame, the time it takes to completely survey and absorb the image can feel abbreviated by the cut. Conversely, if action C is framed closer, it can feel longer since the viewer has “nowhere else to look.” Or to put it another way, closer shots concentrate and enhance dynamism or internal rhythm, and so they generally need less screen time than wide shots.

Zettl expands this idea further by noting that a close up usually carries the same impact as if we are close to an actual subject. In other words, the close up replicates the same proxemics as actually being close. Zettl says, “Long shots and close-ups differ not only in how big objects appear on screen (graphic mass relative to the screen borders) but also on how close they seem to us, the viewers. Close-ups seem physically and psychologically closer to us than long shots.”54

We can see this principle at work in shots at the opposite end of the shot scale from those we looked at in Spartacus. The “Life Lessons” segment of the short film anthology New York Stories (Martin Scorcese, Francis Ford Coppola, Woody Allen, 1989) provides a compelling example. Here, the extreme close up adds energy and increases internal rhythm by narrowing and concentrating the field of view. In the film, the painter Lionel Dobie (Nick Nolte) struggles to complete a number of large works for a show that is opening soon, while struggling to keep his young assistant Paulette (Rosanna Arquette), with whom he shares a loft, in an exploitive relationship. As Lionel struggles for inspiration, he is sexually distracted by the presence of Paulette, who has decided to leave him. See Critical Commons, “Internal Rhythm: ‘Life Lessons,’ Close up and Color Usage.”55

Lionel finally quits procrastinating and gets down to painting. He puts in a cassette of the 1960s blues classic “Politician” by Cream. Director Martin Scorsese opens the scene energetically with a series of tracking shots, but the camera quickly moves in close, as Lionel sees a nude photograph on an art magazine strewn on the floor and seems to take that as a momentary inspiration. What follows is a:30 second sequence of eleven extreme close ups of oil paint squeezed from a tube or swirled onto the canvas, intercut with two extreme close ups of Lionel engrossed in the creative process as he contemplates his next brush stroke. The shot length is short, with an average shot length of 2.5 seconds, so the external cutting rhythm contributes to the burst of creative energy that is expressed in the sequence. But the pinpoint framing of the extreme close-up contributes equally to the aesthetic energy of the scene by heightening the internal rhythm of brush strokes pushing paint into visceral shapes (Figure 8.10).

The paint colors are vibrant, and the kinetic process as Lionel works the material on the canvas is magnified by the narrow field of view, which is only slightly larger than the painter’s hand (Figure 8.10). The framing brings a haptic intensity to the moist textures and fluid physicality of the oil paint as it squirts onto the palette and swirls in broad curves across the canvas, one layer smothering another. The framing also ensures that the motion vectors of Lionel’s aggressive brush across the canvas are essentially mapped “stroke for stroke” across the film screen, an intensification of the brush’s primary motion that communicates the essential qualities of Lionel’s active technique.

Figure 8.10 Internal rhythm: the close up in “Life Lessons” (Scorsese, 1989). The close framing in this sequence ensures that the motion vectors of Lionel Dobie’s (Nick Nolte) hand, aggressively painting his canvas, are essentially mapped “stroke for stroke” across the film screen, an intensification of the brush’s primary motion.

Source: Copyright 1989 Buena Vista Pictures.

Internal Rhythm: Camera Movement

Conventional aesthetics assumes that a moving camera increases internal rhythm more than a static camera. This dynamic “boost” is partly because the move overcomes the limitations of the camera’s fixed aspect ratio – a tilt can show the height of a towering tree, a pan can show the sweep of a river – and partly because the gradual revelation of the profilmic material over time is more dynamic than a fixed shot. Here again, the work of Stanley Kubrick provides many examples of moving camera, particularly the reverse dolly shot that he used extensively. In Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick, 1957) Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas) is leading a regiment engaged in vicious trench warfare in France, while his superior, the ambitious General Mireau (George Macready) tries to engineer a battlefield victory no matter what the cost. Mireau leaves his palatial office and comes to the trenches to fire up the troops for their impending charge “over the top” into “no man’s land.” This is the viewer’s first introduction to the realm of trench warfare, and most of the scene is captured in a single:90 second reverse dolly shot that will match its movements to those of the General. The tempo of both character and camera movement here is deliberate and unhurried, with pauses to converse with the troops. See Critical Commons, “Internal Rhythm: Paths of Glory, Reverse Dolly.”56

Mireau, living in the comfort of a rear echelon, has been largely removed from the reality of the trenches. The scene opens with a wounded man carried away from the camera as Mireau approaches with his aide-de-camp. The general strides confidently and offers breezy salutes to the enlisted men, his crisp uniform and cape at oddly out of place in a dirty trench that is lined with irregular wooden bulwarks. He stops three times to make awkward chat with his foot soldiers, playing up to each with the line, “Ready to kill more Germans, soldier?” The tracking shot pauses for each interlude as the general dispenses platitudes freely. But when he stops to tell a soldier that a rifle “is a soldier’s best friend, you be good to it and it will be good to you,” an exploding shell in the background ironically undercuts the small talk (Figure 8.11).

The general continues his inspection, the camera leading his confident stride through the long trench, and revealing the impressive scale of the battle preparations. He comes to group of soldiers in a fire bay and the steady rhythm of his review comes to an abrupt end, as the camera track pauses for the final time. His question, “Ready to kill more Germans, soldier?” is met with an awkward, extended silence from a soldier who is unresponsive. As the general tries to learn what the problem is, Kubrick turns to traditional coverage for the dialogue scene that follows, and medium close ups of the soldier show his empty stare as he talks vacantly about his wife back home. Appeals from his buddies that he is suffering from “shell shock” (the World War I name for “posttraumatic stress disorder”) are dismissed. “I beg your pardon, Sergeant, there is no such thing as shell shock,” the general counters. The soldier quickly breaks down in fear that he will never see his wife again. The general promptly slaps him and orders him dismissed from the regiment, “I won’t have my brave men contaminated by him.” The scene ends with a tracking shot that follows the general away from the men as his aide-de-camp ironically congratulates Mireau on his decisive action: “You know general, I’m convinced that these tours of yours have an incalculable effect on the morale of these men.”

Figure 8.11 Internal rhythm: reverse dolly in Paths of Glory (Kubrick, 1957). The tempo of both character and camera movement in this long take is deliberate and unhurried, with pauses as General Mireau (George Macready) stops to converse with the troops. The ebb and flow between movement and conversation is adeptly captured by the reverse dolly which simply takes its cue from the pattern of Mireau’s movements.

Source: Copyright 1957 United Artists.

Throughout this scene, there is ebb and flow between movement and conversation, a rise and fall that the reverse dolly is uniquely adept at capturing, simply by taking its cue from the pattern of Mireau’s movements. The unfolding architecture, the scale of the space and the feel of the trench can best be communicated by actually moving through it, not cutting the space into a series of shots. And for the viewer, the rhythm of that “discovery” is controlled completely by the pace and pattern of Mireau’s movements, underscored in the track by a single, crisp military snare drum that evenly punctuates his stroll, and resolves in a drum roll as he pauses. As we noted above, because that sound is non-diegetic – external to the story space – it is ordinarily classified as part of the external rhythm of the scene. We will examine other external rhythm devices below.

Wes Anderson is another filmmaker who uses a range of camera movements throughout his films, in conjunction with very formal compositions and traditional editing structures. In Moonrise Kingdom (Wes Anderson, 2012), he captures the routines of the Khaki Scouts at summer camp with orderly camera moves, impeccably staged military spaces, and exquisitely framed compositions. In the film, Sam (Jared Gilman) resigns from the Khaki Scouts, and runs away with Suzy (Kara Hayward). They are nerdy, innocent adolescents, and they retreat to a secluded island cove that they name Moonrise Kingdom. Eventually, they decide to see if Cousin Ben (Jason Schwartzman) who works at Fort Lebanon, a Khaki scout camp nearby, will marry them. See Critical Commons, “Internal Rhythm: Moonrise Kingdom, Layered Composition in a Tracking Shot.”57