6 Realism and André Bazin

André Bazin, French film critic, co-founder of Cahiers du cinéma in 1951, and “the sound film’s master-thinker and the first to register the effervescence of the cinematic modernism that began to come to prominence during his professional life,” wrote roughly 2,600 articles in the 15 years (1943–1958) he wrote exclusively about cinema. That only 52 of these articles – 26 in English translation – form the basis of what most people know of his ideas has not diminished his stature in the field of film theory, even as scholars have recently tried to expand our understanding of what forms the basis of his theorizing.1

With only a small portion of his writing widely available, Bazin is nevertheless considered one of the most important figures in the history of film theory, second only in the early period to, perhaps, Eisenstein. One reason for this is the emergence of what David Bordwell has called “The Basic Story.” Most early histories of film style tell a similar story, that film became an art form only by casting off its inherent ability to record an event, and embracing its ability to create an event using the resources that are uniquely available to it. Recounted with each new advance in motion picture style – the artificial arrangement of scenes by Georges Méliès, the presentation of simultaneously occurring events by Edwin S. Porter, the perfection of film syntax through flashback and fades by D. W. Griffith, etc. – the history of these stylistic achievements is seen as a step-by-step movement away from the camera capacity to record and towards the emergence of cinema as a unique, creative art form.2

Simultaneously, what Bordwell calls the “Standard Version” of film’s stylistic history was also emerging. In this account, not only was film style moving away from merely recording, this evolution was exposing the innate artistic potentials of the medium.3 Initially, the argument for film as an independent art form, uncovering its intrinsic capacities to create, centered around the potentials of the image – framing, the projection of solids on to a plane surface, the reduction of depth in film, lighting, the monochrome quality of the image, etc. – the fundamental ways in which the medium differed from reality. Film theorist Rudolf Arnheim led this approach. Subsequent theorists (led by Sergei Eisenstein) focused on the potentials of montage – the ability of film to create meaning and affect through juxtaposition of images – as the grounds for demonstrating that film was a new form of art unique from all of the other traditional arts. Given that these intellectuals were bent on promoting cinema as a new art form, the plastics of the image and/or the resources of montage were soon seen to be the essential aesthetic elements unique and specific to cinema. And yet,

From today’s standpoint, such definitions and defenses of the seventh art look decidedly forced. In particular, the idea of medium–specificity has not aged well. It seems unlikely that any medium harbors the sort of aesthetic essence that silent film aficionados ascribed to cinema. There’re too many counterexamples – indisputably good or historically significant films that do not manifest the theorist’s candidate for the essence of cinema.”4

Nevertheless, the formalist theorists – loosely grouped around advocates of the plastics of the image or the resources of montage – would hold sway throughout the silent period, until a dialectical program arose, finding new value in cinema’s faithful representation of the world, and sensing a decline in the use of “montage,” in the sense of abstract, conceptual montage pioneered by the Russians. For even though Russian filmmaking was realistic in its use of non-actors and locations, its use of montage was the height of formal manipulation, since it produced new meanings from simple juxtaposition. This new group of theorists emerged in France and centered around Cahiers. They were led by André Bazin, advocating that “cinema’s artistic possibilities lay exactly in that domain which the silent-cinema adherents despised: representational fidelity.”5 Of course, this new approach, la nouvelle critique, did not reject editing completely. They recognized that in the sound era, traditional découpage had earned its place – unambitious but with time-tested, predictable results:

After 10 years of talking pictures, [Hollywood’s] technicians brought to perfection the most economical and transparent technique possible. The film was made of a series of sequences in plan américan [knees up framing], with some camera movement and a constant play of shot and reverse-shot. . . The movements of the camera were utilized in very precise framings: tracking shot to give the impression of depth, the pan shot to give a sense of breadth.6

Having examined the formalist theories of montage advanced by Sergei Eisenstein, we now consider how theories of realism address editing, in particular how André Bazin thought and wrote about editing as a creative technique in cinema. Writing at a time when cinema was not universally recognized as an art form, these two theorists were at the center of the historical debate whether the realist style or the formalist style of filmmaking is closest to the intrinsic aesthetic capacity of the medium, and fulfills its highest purpose. Here it is useful to simply examine Bazin’s ideas on editing without addressing those larger questions, recognizing that the search for essential characteristics of the film medium is a fruitless search given its diversity of forms. Bazin’s insights about how découpage shapes meaning in film, and particularly how the choice not to cut – i.e., the use of long takes in film – returns the camera to its primary function as a device that records space in the world automatically are original and inventive. “He was without question the most important and intelligent voice to have pleaded for the film theory and a film tradition based on a belief in the naked power of the mechanically recorded image rather than on the learned power of artistic control over such images.”7

Early Life, Philosophical Influences and Ciné Clubs

Bazin’s work as a film theorist was shaped by his early study and struggle as a person deeply engaged in a search for the meaning of his life. Bazin was the son of a bank clerk and lived in La Rochelle, on the Atlantic coast of France in a simple home beside a stream. He loved books, animals and nature, and from his earliest years he collected rocks, bones, feathers, small plants, lizards and turtles. “Reptiles fascinated him most of all because, despite a lifetime of study, he could never quite imagine how they experienced the world. He would watch them for hours and even imitate them, trying to feel what they felt, see what they saw. This genius for sympathetic imagination was the secret of his critical power; for a man prepared to invade the consciousness of an iguana, the consciousness of Buñuel is not an impossible problem.”8

After he graduated from high school, he took an entrance test to attend a teachers’ college – the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Saint-Cloud – that was ranked as one of the best in the public system, and he spent three years there on a scholarship, hoping to begin a career in education within a system steeped in positivism, a philosophy that rejected anything other than assertions subjected to logical or mathematical proof. France has traditionally maintained one of the most highly centralized, rigid and hierarchical education systems in the world. Bazin felt immediately alienated by the rigid educational goals of Saint-Cloud and fell under the influence of Henri Bergson, the famous French philosopher of the early twentieth century:

Against the dominant positivism [Bergson] invoked higher science, one that would encompass the experience of nature, not merely the facts of nature. He thereby gathered to him certain factions of the scientific community, the greater portion of the artistic community, and a strain of theologians, all of whom were looking for a philosophical vocabulary capable of describing man in an animated and evolving universe.9

Bergson argued that there are three methods of experiencing the world: raw perception, rational thought and intuition. Perception provides us the most basic sense data about the world. Reasoning allows us to organize those perceptions into coherent patterns. Intuition is more transcendent, allowing human beings to return to the experience of the thing itself. When we pick out a single bird song from a cacophony of birds singing in a meadow, we don’t analyze the individual notes and construct the singular song through rational thought, we simply catch the bird’s melody by intuition, a form of thinking beyond logic that allows us to grasp meanings from a world in constant flux. Bergson would provide a basis for Bazin’s film theory because Bazin shared his respect for the unity of universe in flux, and thus, from the outset, saw the shot and analytical editing as less revealing than the greatest films for which “there remains henceforth only the question of framing the fleeting crystallization of the reality of whose environing presence one is ceaselessly aware.”10

Bazin served for a while in the French army, but with the Nazi takeover of France in May–June, 1940, Bazin sank into a deep despair, and he spoke openly about the failure of French institutions like the clergy and the press who made accommodations towards Nazi rulers. He returned to St. Cloud to take his examinations to enter a teaching career, but found that he could barely tolerate the hypocrisy he found there under the occupation. “He saw French education as a wasteful and debilitating institution that rewarded blind adherence to red tape and ‘tradition.’ ”11 Since St. Cloud turned out school administrators, Bazin saw this intransigence throughout the institution. Bazin passed his written exam, but failed his oral exam because, in his nervousness, his tendency to stutter rendered him almost unable to speak. Bazin also suspected his blunt criticism of St. Cloud did not help, and though the examiners were split and encouraged him to try again, in the next few years, Bazin would question deeply the French educational system, while turning his course towards the informal companionship he found in organizations of public intellectuals, in writing for highbrow journals and daily newspapers, and seeking his own definition of the value of his life.

During the war, following the “youth fad” in Germany, groups of young people were organized in Vichy France under the Jeunes du Maréchal, a kind of right wing, anti-communist, nationalist youth group. At the Sorbonne, an opposition movement arose to organize groups of youths with credible left wing credentials into four “houses” – one for arts, letters, law and science – to maintain cultural activity in the face of the occupation. Bazin was among the first recruited and made the Maison des Lettres his refuge for the next few years. With no official coursework, he lived in a dormitory at the university with the sole purpose of organizing cultural events and study groups in theatre, urban architecture, the modern novel, and popular entertainments like the circus. A fellow student posted a notice for help starting a cinema study group, and Bazin’s path forward in film was launched.

It would be a daunting journey. As Dudley Andrew points out, the contempt for motion pictures at the Sorbonne extended into the culture at large:

It is difficult for us in our age to feel the depth of contempt in which cinema was generally held in the period. There had been a flowering of ciné-clubs in the late twenties and early thirties in France, but by the time of the invasion there were literally no ciné-clubs or any serious journals devoted to the art. Once the sound film came into use, most intellectuals placed the cinema beside the circus as a popular art not warranting reflection. The cult of star and the dominance of Hollywood in the thirties solidify this view.12

Bazin’s efforts were further hampered by the technology itself. It is difficult in the age of the internet to recall how hard it was to find film prints and a projector to screen films. With traditional cinemas under the censorship of the Nazis, Bazin would travel around Paris to camera shops looking for interesting 8mm prints – the amateur format – that he would show to groups of 25 or 30, and lead a discussion with whoever would stay afterwards. Alain Resnais became a supporter, and a useful one, since he had already made a few experimental films, had a 9.5mm projector and prints of interesting films by Buster Keaton, Fritz Lang and others that Bazin had not seen. After the screenings at venues around Paris, Bazin would dominate the discussions, taking each new film as a point of departure for an inquiry in to shot selection, lighting, staging, etc. This was a passionate, life changing endeavor for the young man, barely 25 years old, who had transformed himself in to a bohemian film critic: “Bazin had entered the Maison des Lettres with an interest in cinema scarcely greater than his interest in anything else: animals, literature, philosophy; but the end of 1943, film has become a passion which never left him.”13 That same year, he wrote his first published works, telling his readers of his desire to teach them everything about cinema, to become a kind of school for the spectator, to demystify how films are made, to explicate their aesthetics, to uncover their economics, psychology, and sociology.14 As he read and studied more about philosophy and film, he continued to forge new outlets for his writing in journals and the popular press, which had largely ignored serious criticism of motion pictures. It was a fortuitous moment, because the postwar world would be different, with a different concept of what motion pictures could be, and Bazin’s work would help identify and legitimize the foundations of this emerging art.

Theorizing Film

By 1945, Bazin had written one of his seminal works, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” Bazin’s first principle is that there is in man the desire to reproduce the world in a perfect, life like manner, to literally “embalm time,” to conquer death by a complete representation of the world, of the subject, that would be timeless. This desire, which he compares to man’s desire to fly, is integral to all of human culture. For example, Egyptian mummies “by providing a defense against the passage of time [satisfied] a basic psychological need in man, for death is but the victory of time.”15 Similarly, man’s efforts at faithful reproduction in painting – perspective painting in the Renaissance that created the illusion of depth, and the Baroque era’s pursuit of the representation of motion – are seen by Bazin as ill conceived attempts to combine spiritual expression with a complete imitation of the external world. According to Bazin, “Perspective was the original sin of Western painting,”16 because it is pseudo realism, a painterly deception. Continuing the metaphor, Bazin saw photography and cinematography as “redeemers” because their essence is the realism that man constantly seeks; these new media have freed painting from its preoccupation with reproduction, satisfying the need of the mass audience for “realism” and allowing modernist painters to move on to other issues.

Whereas realism in painting is always suspect because the hand of the artist intercedes between the object and its reproduction, photography produced a radically new psychology of the image. Photographs have a credibility lacking in other methods of making pictures:

We are forced to accept as real the existence of the object reproduced, actually re-presented, set before us, that is to say, in time and space. . . For the first time, between the originating object and its reproduction there intervenes only the instrumentality of a nonliving agent. For the first time, the image of the world is formed automatically, without the creative intervention of man. . . All the arts are based on the presence of man, only photography derives an advantage from his absence. Photography affects us like a phenomenon in nature, like a flower or a snowflake.”17

In order to reinforce this idea of “transference of reality” from the object to the photograph, Bazin constructs metaphors in his writings that try to get at this puzzling connection, comparing the photograph/object to fingerprint/finger, in that both share a common being that permits their existence.18 Elsewhere he compares photography to a mold, in that it takes an impression in light from the object photographed.19 The photograph has an almost mystical connection to the object it captures, like the veil of Veronica20 or the shroud of Turin.21 Like each of these examples, there is a direct linkage between photograph and object that confers on the image an immediate realism. The photograph frees the object from its spatial and temporal bounds because of this ontological linkage: “No matter how fuzzy, distorted, or discolored, no matter how lacking in documentary value the image may be, it shares, by virtue of the very process of its becoming, the being of the model of which it is the reproduction; it is the model.”22

These metaphors also hint at the giveness of photography’s objectivity, a factor that may account for the human fascination with photographs, in combination with the overwhelming level of visual detail they capture. But since photography can only capture a single moment, for Bazin it is feeble when compared to cinema, which can take a mold of an object and an imprint of its duration.23 In short, “the cinema is objectivity in time.”24

For Bazin, the camera’s automatic recording of reality makes its objectivity axiomatic. As Eric Rohmer wrote in tribute to Bazin immediately after his passing, “Each essay and indeed the whole work itself fits perfectly into the pattern of the mathematical demonstration. Without any doubt, the whole body of Bazin’s work it’s based on one central idea, affirmation of the objectivity of the cinema in the same way as all geometry is centered on the properties of the straight line.”25 In practical terms, Bazin was consistent, but his method of theorizing was never as broad and as systematic as mathematics, because his ideas grew from the articles on contemporary cinema he wrote about ceaselessly for in the popular/intellectual press. Though he wrote a short book on Orson Welles, a collection of short essays on Chaplin, and was working on a book about Jean Renoir when he died of leukemia at age 40, his work was mostly in essay form where he would watch a film, try to experience it objectively without preconceived notions, and then write about the fundamental issues that the film suggested to him. As Andrew puts it, “Bazin begins with the most particular facts available, the film before his eyes, through a process of logical and imaginative reflection, he arrives at a general theory.”26 This approach is consistent with the contemporary movement in French thinking driven by the magazine Esprit, and the writer Emmanuel Mounier known as personalism, that locates the human person as the ontological and epistemological starting point of philosophical reflection. Bazin’s immersion in the thinking of Mounier – as well as the existentialist writings of Sartre, Marcel and Merleau-Ponty – ties together his objectivity axiom and his theorizing. Bazin sees ambiguity as an essential attribute of reality, not a limitation of our ability to perceive what is real. He sees in external reality a “mysterious otherness:”

Mournier taught that this otherness, while inexhaustible, can be known in part by the properly trained person. Such training produces a self-effacing listener, whose senses, mind, and soul are focused on the physical world, waiting for it to make itself known little by little. . . [For] existentialists reality is not a situation available to experience but an “emerging something” which the mind essentially participates in and which can only be said to exist only in experience.27

Fundamentally, Bazin’s theory rests first on the idea that no occurrence in the world has an a priori meaning – the world in flux is simply that, nothing more, and a flower blooming is not a sign that there is a supernatural being watching over the universe. Secondly, it rests on the notion that “The cinema’s ontological vocation is the reproduction of reality by respecting this essential characteristic [i.e., the ambiguity of reality] as much as possible. The cinema, therefore, must produce, or strive to produce, representations endowed with as much ambiguity as exist in reality itself.”28

This notion of “experiencing ambiguity in reality” is central to two films Bazin champions for their realist style:: “The two most significant events in this evolution [towards realism] in the history of the cinema since 1940 are Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) and Paisà [Rossellini, 1946].”29 Welles was the actor/director/radio producer and enfant terrible who came to Hollywood from New York’s Mercury Theatre. Welles had gained immense notoriety with the live broadcast on October 29, 1938 of the H. G. Wells classic War of the Worlds, which caused widespread panic when many listeners were convinced that Martians were invading the U.S.

Rossellini was one of the early giants in the Italian neorealism30 movement, a body of work that emerged in postwar Italy that rejected the well-made studio film for “found stories” of common people that would provide thematic credibility with audiences experiencing the deep-rooted social problems laid bare by the devastation of World War II. Shot in the streets for visual authenticity, often with non actors, neorealist films routinely examined the simple struggle to survive with scenes of the poor and the lower classes going about the mundane activities of their daily lives. Rossellini grew up in a cinema – his father opened the first movie theater in Rome – and he worked early in his career as a sound engineer. Why did these directors hold such a special place for Bazin?

Dudley Andrews suggests that they were, in many ways, simply kindred spirits. In Bazin’s view, reality is the result of an active perceiver and his encounter with a field of phenomena. Cinema, as an apparatus that engages the world, is an instrument with a parallel function, and Bazin’s theorizing is, in large part, simply preparing us for what cinema can reveal to us about the world. In spite of their differences in style, Bazin found purpose and pleasure in trying to account for the incredible emotion he felt seeing Paisan (Rossellini, 1940) and Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941).

Welles and Rossellini share an attitude toward filmmaking that makes it more of an exploration than a creation. . . These films marked out for [Bazin] the spectrum of his interests, for Paisa examined a political reality which was even then struggling to come into existence while Citizen Kane explored more abstractly man’s position in time and space. . . both attempt, in different ways, to record and preserve the complexity of our encounters with the world.31

In “From Citizen Kane to Farrebique,” Bazin compares the film styles of both Welles and Rossellini with the yardstick of continuity editing (découpage classique or the Institutional Mode of Representation), where shot changes duplicate the changes in attention of the observer so seamlessly that the viewer rarely notices that the event has been fragmented. While Bazin does not deny that traditional découpage has earned its place in cinema, he argues that what makes the technique possible is the inherent realism of the film image:

Under the cover of the congenital realism of the cinematographic image, a complete system of abstraction has been fraudulently introduced. One believes limits have been set by breaking up the events according to a sort of anatomy natural to the action: in fact, one has subordinated wholeness of reality to the “sense” of the action. One has transformed nature into a series of “signs.”32

In other words, as the director’s sense of the action at the shooting stage dictates what camera placements and framings are selected, reality is made to serve a prior logic, rendering the shots as simple signs, bearers of meaning other than what they mean in themselves.

Bazin on Rossellini and Paisan

Bazin moves directly to contrast this kind of traditional découpage with the work of Rossellini in Paisà (aka Paisan Rossellini, 1946). No longer are shots signs, because Rossellini camerawork – though selective – respects the “ambiguity in reality,” so prized by Bazin: “The unit of cinematic narrative in Paisà is not the ‘shot,’ an abstract view of a reality which is being analyzed, but the ‘fact.’ A fragment of concrete reality in itself multiple and full of ambiguity, whose meaning emerges only after the fact, thanks to other imposed facts between which the mind establishes certain relationships.”33 Three key concepts are expressed here. First, Bazin acknowledges that, even in the realist style, the director selects reality by use of the camera. Second, Bazin recognizes that the director will arrange (impose) these selections with others. Finally, if the director respects the factual integrity of the shot by capturing a fragment of reality that is multiple and ambiguous, then the viewer’s mind will establish certain relationships – in other places Bazin calls these correspondences after the poet Baudelaire34 – so that a kind of meaning will emerge a posteriori from the scene. In this way, Bazin attempts to distinguish the realist approach to filmic construction – a recording – from traditional découpage – a telling.

Bazin argues that the neorealist approach in Paisà is unique, first, in its episodic structure, which links six stories that occur as Italy is being liberated by the Allies. The film opens with the invasion of Sicily, but after that, there is no indication of the temporal relationships between the short stories which cover an American soldier and a local girl who are killed in a castle by the sea, a street kid from Naples who sells the clothes of a drunk African American soldier, etc. See Critical Commons, “Ellipsis in Paisan: ‘Like Stone to Stone Crossing a River’ – André Bazin.”35 Bazin sketches in broad strokes a poignant sequence from the final installment,

1) A small group of Italian partisans and Allied soldiers have been given a supply of food by family of fisher folks living in an isolated farmhouse in the heart of the marshlands of the Po delta. Having been handed a basket of eels, they take off. Some while later, a German patrol discovers this, and executes the inhabitants of the farm. 2) An American officer and a partisan are wandering at twilight in the marshes. There’s a burst of gunfire in the distance. From a highly elliptical conversation we gather that the Germans have shot the fisherman. 3) The dead bodies of the men and women lie stretched out in front of the little farmhouse. In the twilight, the half-naked baby cries endlessly.36

Bazin acknowledges that Rossellini has left enormous ellipses in these events. (And in fact, in describing the scene, Bazin omits a scene where soldiers light flares to attract an Allied plane that is trying to rescue a OSS officer, which is a central premise for the story.) Bazin reminds us that it is common for directors to use ellipses, and in traditional découpage, these omissions will ordinarily allow the easy, seamless movement from cause to effect. But Bazin claims Rossellini’s ellipses are different, creating a film whose events drive the story not like a sprocket and bicycle chain, but in a fashion much looser: “The mind has to leap from one event to the other as one leaps from stone to stone in crossing a river. It may happen that one’s foot hesitates between two rocks, or that one misses one’s footing and slips. The mind does likewise [with this film].”37

Here is another of Bazin’s enduring metaphors, the idea that the realist film asks more of the viewer. Just as one must find one’s own path in crossing a river stone by stone, so the realist film asks the viewer to make their own connections between the “stones,” the narrative events that are present in the film. By honoring the ambiguity inherent in the events, the realist filmmaker challenges the viewer to link the narrative events in a process that may move forward in fits and starts, that may cause one to hesitate, to occasionally “slip.” This metaphor is so integral to Bazin’s thinking that it is worth considering an expanded version he wrote later. Classical art (and classical film) is a form of “bridge” constructed with “bricks” – basic units of meaning pre-formed to fit together into a structure. By contrast, neorealist films are made with facts, “rocks scattered in a ford” whose meaning is not pre-determined. These rocks are not affected by the mind that connects them to lead across a river, and yet,

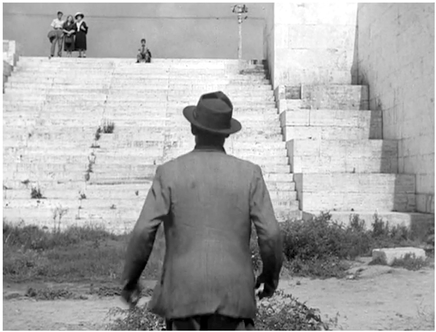

Figure 6.1 Paisan (Rossellini, 1946). André Bazin argues that Rossellini’s editing in Paisan creates “an intelligible succession of events,” but asks more of the viewer. Just as one must find one’s own path in crossing a river stone by stone, the realist film asks the viewer to make their own connection between the “stones,” the narrative events that are present in the film. Here, the crying baby standing with the dead bodies of his parents is a “fact” that forces us to make narrative connections.

Source: Copyright 1946 Arthur Mayer & Joseph Burstyn.

If the service which they have rendered is the same as that of the bridge, it is because I have brought my share of ingenuity to bear on their chance arrangement; I have added the motion which, though it alters neither their nature nor their appearance, gives them a provisional meaning and utility. In the same way, the neorealist film has a meaning, but it is a posteriori, to the extent that it permits our awareness to move from one fact to another, from one fragment of reality to the next, whereas in the classical artistic composition the meaning is established a priori: the house is already there in the brick.38

So the conventional filmmaker uses “bricks,” shots shaped for a predetermined usage or meaning, and strings them together one after another, and découpage constructs the house, the narrative of the film, much like Pudovkin’s “links in a chain” seen in Chapter 5. Likewise, stones mesh together seamlessly to form a bridge. What matters in both cases is that they fit together to build the structure. But the realist filmmaker uses shots that are unaltered in nature and appearance and “scattered in a ford” like mere rocks found in a river crossing. These rocks are objective facts that will never be affected or altered, simply used to create a provisional meaning assembled by the viewer.

Returning to Paisà, Bazin finds authenticity in the fact that in shot 2, distant gunfire is the basis for the partisans’ deduction that the farmers are dead: it is a sound they would know well. Bazin finds particular significance in the final shots of the baby (Figure 6.1), because the baby exhibits “presence,” and the camera does not analyze that fact in a predetermined way. How the farmer died will never be known, but the baby remains a real presence, a fact that seems to exist independent of how the viewer uses the baby to imaginatively construct the story.39 The baby is a haunting presence that lingers, no doubt. But for contemporary audiences, the realism in Paisan is a mixed bag. The performers are almost exclusively non-actors and the amateur acting is overt and flat in places. Despite its remarkable feeling for real places and the cultural milieu, overt underscoring tries to smooth its disjointed structure in places, and truncated resolutions of the episodes often feel forced. Bazin himself concedes, “Unfortunately the demon of melodrama that Italian film makers seem incapable of exorcising takes over every so often, thus imposing a dramatic necessity on strictly foreseeable events.”40

Yet, we can understand Bazin’s admiration for its unique, personal approach to the work and for the potent mirror it held up to the problems of postwar Europe. He also respected Rossellini greatly, because this film marked a seminal convergence in Bazin’s career that would affect him deeply:

[A] sense of the harmony between art and life, between France and Italy, between philosophy and politics overwhelmed Bazin one evening late in 1946 in Paris, when he arranged for the French premier of Paisà. Rossellini drove up from Rome with the film and. . . The crowded audience of workers, intellectuals, former resistance fighters and prisoners of war saw what was for Bazin perhaps the most important and revolutionary film ever made.41

Bazin spoke afterward, and though he was initially overcome with emotion, he rallied the audience as he explained his reaction to the film, creating one of those electric moments that shapes in some small way the course of film history. He continued to speak about the film for days afterwards, and wrote a wonderful essay about the film a month later. Rossellini was forever grateful that Bazin had situated the film so that it would be widely appreciated in France. And Bazin was not alone in recognizing the film. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised the film as extraordinary, “the antithesis of the classic story film. . . a milestone in the expressiveness of the screen . . . a film to be seen – and seen again.”42

While it remains difficult for us today to appreciate the contemporary response that Paisan generated, the special critical approach of André Bazin, who took every film on its own terms and appreciated each for its own values, is clearly at work here. In a wider context, perhaps we find here the budding concepts of le caméra-stylo and la politique des auteurs that would emerge in a few years and form a central concern of Cahiers du Cinéma when the magazine launched in 1951. Le caméra-stylo means literally “camera-pen,” the concept advanced by film critic and director Alexander Astruc in 1948 that film directors should use their cameras like writers use their pens, as an instrument of individual expression. Astruc saw cinema moving away from its roots as spectacle and literary adaptation. Now the film artist can “express his thoughts, however abstract they maybe, or translate his obsessions exactly as he does in the contemporary essay or novel. This is why I would like to call this new age of cinema the age of the ‘caméra-stylo.’ ” 43 Central to this position was Astruc’s belief that there is no longer any need to maintain the traditional division of labor where the director merely stages a scene from the script. Rather, directing – in the hands of certain directors – becomes an authentic act of writing.

Six years later, François Truffaut would write his contentious article, “A Certain Tendency of the French Cinéma,” which would fix the term la politique des auteurs (literally “a policy of authors,” translated in English as the autuer theory) which argues that certain directors deserve to be called the author of their films, because their vision drives the artistic control of the film. So rather than viewing filmmaking as an art form created by a collection of artists, the Cahiers critics – not only Truffaut, but Godard, Rivette and Chabrol – began to advocate for pivotal directors, known and unknown, as auteurs, which in the simplest application of the critical-theoretical term, describes a filmmaker whose body of work exhibits personal vision and stylistic consistency. In this context – a culture of film criticism advocating for a revitalization of the cinema with a provocative doctrine championing the work of auteurs, particularly American auteurs – Bazin continued to argue against putting the filmmaker above the work, against putting the individual director above his more “botanical” view that saw these “auteurs as distinctive flowers produced by complex organism and nourished by a very special soil, the ideology of American society.”44 More interested in classifying films in genres, we can still see in Bazin’s elevation of Rossellini (as well as Welles and Renoir) the roots of auteurism, an admiration not simply for the realistic style of the work, but also for the consistency and the integrity that often required the artist to break out of the system which constrained their work. For contemporary audiences, Paisan seems an odd film to place on par with Citizen Kane, because the plodding dialogue and the overly lush music tends to undercut the drama inherent in the locations of the partisan struggle. But given the revolutionary aesthetic Rossellini discovers to create Paisan, the realism so deeply rooted in contemporary postwar Italy, Bazin’s early recognition of its international significance is justified.

Bazin on De Sica and Bicycle Thieves

Vittorio De Sica (1901–1974) was born into poverty in Sora, Italy and became a stage actor in the early 1920s. With his wife Giuditta Rissone, De Sica founded a theatre company a decade later and performed mostly comedic fare with significant directors like Luchino Visconti.

His meeting with Cesare Zavattini, one of the most prolific Italian screenwriters who penned over 80 screenplays in his lifetime, marked the beginning of a very productive collaboration. Together they created Shoeshine (1946) and Bicycle Thieves (1948) both of which won Academy awards. When Bicycle Thieves was released, Bazin was already speculating whether neorealism had a future, but he found in this film all of the compelling elements of the movement: a motion picture filmed entirely in the streets, with no studio shots, using players with no previous acting experience, and a plot that was partly improvisational. De Sica spent many months auditioning and casting the film in order to find players with “natural nobility, that purity of countenance and bearing that the common people have.”45 He found two remarkable novice performers: the factory worker Lamberto Maggiorani, who plays the father struggling to feed his family Antonio Ricci, and Enzo Staiola, a seven-year-old who plays his son Bruno.

Bicycle Thieves does not have the constructed plot of a traditional motion picture, but rather grows from a truly “ . . . insignificant, even a banal incident: a workman spends a whole day looking in vain in the streets of Rome for the bicycle someone has stolen from him.” 46

The man has as new job hanging movie flyers and without his bike, he will lose his job. Late in the day, after hours of fruitless wandering, he tries to steal a bicycle. Caught by the police but released, he feels shame at having stooped to the level of the thief. Unlike the classic Hollywood film, where the psychologically well-defined protagonist is center stage, here the focus in on the socioeconomic obstacles that confront the father, hurdles foregrounded by placing him in a very difficult economic situation. Bazin argues that Bicycle Thieves does not cheat reality, but treats each narrative in the event in a way that respects its natural occurrence:

In the middle of the chase the little boy suddenly needs to piss. So he does. The downpour forces the father and son to shelter in a carriageway, so like them we have to forgo the chase and wait till the storm is over. The events are not necessarily signs of something, of a truth of which we are to be convinced; they all carry their own weight, their complete uniqueness, that ambiguity which characterizes any fact.47

De Sica’s style is neutral, without pointed close ups to tell the audience what to think about next. He retains the “phenomenological integrity” of his scenes by clear camera placement, by reframing rather than cutting, and by using tracking shots extensively, in a range of framings. See Critical Commons, “Bicycle Thieves: Neorealism and Camera Movement, the Tilt.”48 Early in the film, the workman goes to the pawnshop with his wife to retrieve his bike so that he can take his new job as a poster hanger. The wife pawns the bed linens that were part of her dowry in order to pay to get the bike out of hock. As she negotiates with the pawnbroker through a window in a translucent glass divider, the husband inserts himself into the window to ask for more money. His naturalistic appearance into the conversation creates a “shot change” from a single shot to a “two-shot” that respects the space of the scene, emphasizing their shared interest, the barrier between them and the stereotypical world of the pawnbroker, playing on the tribulations of the working poor. The man shows them a touch of mercy, granting them an extra 500 lira.

As the husband waits to redeem his bicycle, he sees the clerk take the bed linens to the back of the store. At first, it appears that the clerk will place them with other linens that occupy a couple of rows of shelves. But the clerk begins to climb to the shelving and the wide shot tilts up to follow him, revealing that there are actually six immense shelves holding hundreds of pawned linens, the slow tilt up revealing in this small corner of Rome, the immensity of the economic misery facing the Italian working class (Figure 6.2).

By shooting in gritty streets that are not the scenes we typically associate with Rome, De Sica creates a natural, flow of life quality to the search for the bicycle: the locations are ordinary Rome, not extraordinary Rome. Throughout the film, the workman’s son Bruno stays close by his father’s heels, helping him look through the markets where they think the bicycle might have been “chopped” and sold for parts. Bazin finds this pairing to be pivotal in the film. The boy adds a personal, ethical dimension to the story, which otherwise would have been only a sociological study. The boy provides accompaniment or counterpoint to his father’s purposeful gate, and De Sica “wanted to play off the striding gate of the man against the short trotting steps of the child, the harmony of this discord being for him of capital importance for the understanding of the film as a whole.”49

The position of Bruno as they walk is telling, an emotional barometer of the state of their feelings towards each other. At one point, they are caught in a downpour and Bruno sticks close as they search helter-skelter through the chaos of a market place that is folding up, as vendors and buyers seek shelter. The rain drenches them. Father and son look to each other for some kind of guidance as the camera tilts between them: should they continue or surrender to the rain? Ultimately they give up and take cover, Bruno falling on the curb as they race for cover. As Bruno wipes the grime off of himself furiously, his father is oblivious, asking, “What happened?” Bruno gestures to the curb and answers indignantly, with that certain Italian flair, “I fell!” The father hands him his handkerchief to wipe with and touches the boy’s head tenderly. Seven Austrian clerics then rush in for cover from the rain, surrounding the father, prattling in German and pinning Bruno against the wall (Figure 6.03). Bruno is in no mood to be respectful, and he quickly shoves the clergyman out of his space.

Figure 6.2 Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948): camera movement instead of cutting. In Bicycle Thieves, De Sica uses camera movement to reframe action rather than cut, often to make a point. At the pawn shop, a wide shot tilts up to follow the clerk climbing a ladder, revealing that there are actually hundreds of pawned linens, the slow tilt revealing the immensity of the economic misery facing the Italian working class.

Source: Copyright 1948 Ente Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche.

As the rain shower ends, the scene ends and the clerics go on about their business. Bazin writes that these “events are not necessarily signs of something, of a truth of which we are to be convinced; they all carry their own weight, their complete uniqueness, that ambiguity which characterizes any fact. So if you do not have the eyes to see, you’re free to attribute what happens to bad luck or chance.”50 Bazin, on the other hand, sees correspondences, a kind of meaning that grows a posteriori from the downpour scene, because it is “another stone in the river,” part and parcel of a society that is unhelpful in the face of the man’s personal tragedy, the uncaring world that he has met at every turn. “On that score, the most successful scene is that in the storm under the porch when a flock of Austrian seminarians crowd around the worker and his son. We have no valid reason to blame them for chattering so much and still less for talking German. But it would be difficult to create a more objectively anti-clerical scene.”51

Later in the film, the pair follow an old man into a church that ministers to street people, because they think he can give them information about the stolen bike. The old man gives them the slip, and they rush out of the back of the church frantic to find him. See Critical Commons, “Bicycle Thieves: Bruno’s Spatial Relation to his Father after he is Hit.”52 Bruno remains close, as the camera tracks with them, but his hopes are fading. Bruno blames his father for letting the old man escape, and his father slaps him in the face in frustration and anger. There is a long moment of sorrowful contemplation, played out in alternating medium close ups, as they both let that transgression sink in, and then De Sica cuts wide as Bruno moves away from his father crying, with the camera tracking their separation. Bruno latches onto a tree, half defiant, half afraid, and says his father will have to go on alone. As Bruno relents and they begin to move on, the argument continues in single tracking shots with Bruno threatening the ultimate consequence: “I’m going to tell Mama what happened when we get home.” The sequence ends with father and son physically separated as the camera tracks with them (Figure 6.4), a telling moment according to Bazin, “Whether the child is ahead, behind, alongside – or when, sulking after having had his ears boxed, he is dawdling behind in the gesture of revenge – what he is doing is never without meaning. On the contrary it is the phenomenology of the script.”53 The sequence ends as the father tells Bruno to go wait on a nearby bridge.

Figure 6.3 Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948): correspondences. Bazin sees correspondences, a kind of meaning that grows a posteriori from the downpour scene when a flock of Austrian seminarians surround the worker and his son. “We have no valid reason to blame them for chattering so much and still less for talking German. But it would be difficult to create a more objectively anticlerical scene.”

Source: Copyright 1948 Ente Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche.

The father continues searching up and down along the river. He hears someone cry for help back towards the bridge where he left Bruno. A commotion ensues, people running towards the river, shouting that a boy is drowning in the river. Panicked, the father races back to the bridge – he thinks his boy has fallen in – and waits pensively as people in a boat pull two swimmers from the river. He breathes a sigh of relief that the person they drag to shore is not his son, then turns to see the tiny Bruno standing at the top of an immense stairway (Figure 6.5). The low camera placement and wide scope make the boy seem somehow more fragile, more precious in the eyes of the worried father, and he races up the steps to be reunited with his son.

As they walk off – united again as a family – the father tells the boy to put his jacket back on before he catches a chill. In these two street scenes that flow effortlessly forward as the day of searching progresses, De Sica has moved the viewer through the pair’s frustration, the transgression of the slap, the shame and recrimination that bubbles up in its wake, the raw panic of the father who fears for his child’s life, and their ultimate reunion. De Sica’s découpage, while conventional in some respects, is always fluid and respectful of the spatial arrangement of these moments between the pair, careful to render the boy’s position an emotional and moral indicator naturally embedded in the story, like river stones for those who can discover the connections. For Bazin, the boy’s actions are simple, but the ethical correspondences he embodies are part of the particulars presented:

Figure 6.4 Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948): tracking shot and relative position. De Sica used the tracking shot showing the relative position of Bruno searching with his father as an emotional barometer of the state of their feelings towards each other.

Source: Copyright 1948 Ente Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche.

In fact, the boy’s part is confined to trotting along beside his father. But he is the intimate witness of the tragedy, its private chorus. It is supremely clever to have virtually eliminated the role of the wife in order to give flesh and blood to the private character of the tragedy in the person of the child.54

This role of witness culminates at the end of the film, when the workman’s desperation to find his bicycle intensifies. His emotional barometer is, again, the boy, and the father’s despair registers as indifference to his son’s safety. See Critical Commons, “Bicycle Thieves: Bruno’s Spatial Relation to his Father as the Film Ends.”55 As the father crosses a yet another street downcast, the boy tags far behind, dodging one car, before another one skids to avoid hitting him. They round a corner to see a soccer stadium and the boy sits down on the curb, exhausted from the search. For roughly the next three minutes, the boy anchors the corner where the father will sway back and forth in a kind of soul searching dance, struggling to decide whether or not he will steal a bike in order to feed his family. De Sica’s staging here is brilliant, and alternates between chest high wide shots of the workman pacing back and forth between the stadium and the unlocked bike standing near a doorway behind him, and point of view long shots of both ends of that line of action: at one end, a lone policeman strolling among a sea of bicycles parked for the soccer match and at the other, a lone bicycle sitting unattended leaning against a doorway. For a moment, the father hesitates and returns to sit with Bruno on the curb. His anguish is magnified as the camera pushes in, literally moving through a team of bicycle racers that flash by in front of him.

Figure 6.5 Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948): staging in depth. Panicked that his boy has fallen in the river, the father turns and De Sica uses the wide scope and low placement of the camera to make the boy seem somehow more fragile in the eyes of the worried father.

Source: Copyright 1948 Ente Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche.

When he rises and looks towards the stadium, the camera slowly pans across a river of people leaving the stadium. He paces again away from the stadium and as the camera tracks around the corner with him, the sidewalk clears revealing the lone bicycle still standing by the doorway (Figure 6.6).

He paces back towards the stadium, and a sea of soccer fans remove their bicycles from a rack and begin to set off for home. The workman takes off his hat, and returns once more to the lone bicycle, this time gripping the hair on the back of his head, distraught, but knowing what he has to do. He gives Bruno some money, sends him off to catch the streetcar, and tells him where to wait for him. Bruno hesitates and the father drives him away, the camera tracking around the corner again to reveal the lone bike. The father circles the lone bicycle tentatively, then pounces on it, only to be immediately spotted by the owner who shouts, “Thief! Stop him! Thief!” alerting passersby in the street who give chase.

The chase is short lived. The workman races around the corner on the stolen bike, followed closely by a band of men giving chase. The chase continues around the block, returning to the same corner where he started from, and De Sica cuts to Bruno, who missed the streetcar, looking on intensely, and as the camera tracks closely around him, it reveals the moment of realization that his father is a thief. A scuffle ensues as the father is caught, and a policeman summoned. The camera alternates between close shots of the fearful Bruno, waist high in a sea of angry men, tugging at this father’s coat and shouting “Papa!” and shots of the irate crowd above him pelting with slaps to the back of his head and to his face. The business of the angry crowd continues: as a street car pushes to pass, they drag the workman to the sidewalk, and Bruno is left to pick up his father’s hat, dust it off and walk behind him. De Sica gives us the boy’s face in a medium tracking shot that registers the boy’s slow, sorrowful walk. The boy is now a tearful accomplice, walking and dusting the hat, a trace of his father’s former dignity (Figure 6.7).

Figure 6.6 Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948): staging in depth. As the father agonizes about stealing a bike, De Sica’s staging alternates between wide shots of the workman pacing back and forth in a kind of soul searching dance.

Source: Copyright 1948 Ente Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche.

The angry crowd continues to constrain the father, but the bike’s owner, seeing the boy walking up to look on, ultimately decides not to press charges. As the men push the humiliated workman off on his way, warning him not to return, De Sica returns to his faithful tracking shot to end the film. Ten tracking shots follow to end the film, showing the faces of the boy and his father, overcome by events, and walking in the crowds surrounding them, and culminating in a moment where the father bursts into tears. Bruno takes his hand, one of their closest moments in the entire film, and they simply walk, together in their own thoughts (Figure 6.8). The final wide shot is static, traditional and summative: the pair walks away from the camera surrounded by a sea of strangers moving the same direction, facing an uncertain future, down a street that stretches deep into the city.

Here, Bazin’s summary of the film’s closing theme is typically concise and insightful. The father’s humiliation in the street has been witnessed by his son, and their relationship is changed forever.

Up to that moment the man has been like a god to his son; their relations come under the heading of admiration. By his action the father has now compromised them. The tears they shed as they walk side by side, arms swinging, signify their despair over a paradise lost. But the son returns to a father who has fallen from grace. He will love him henceforth as a human being, shame and all. The hand that slips into his is neither a symbol of forgiveness nor of a childish act of consolation. It is rather the most solemn gesture that could ever market relations between a father and his son: one that makes them equals.56

Figure 6.7 Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948): medium tracking shot. De Sica places Bruno’s face in a medium tracking shot that reveals the boy walking and dusting off his father’s hat, a tearful accomplice to his shameful theft.

Source: Copyright 1948 Ente Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche.

Bazin on Welles and Citizen Kane

As the auteur theory took center cage at Cahiers du Cinèma, Bazin was sympathetic but remained skeptical of the romantic notion that a film springs from the single mind of the director, and leery of all the attention given to American filmmakers. Orson Welles was different in Bazin’s eyes, however, because he was new to Hollywood, very young, edgy and creating truly innovative work. Many of his innovations grew out of his experience in radio, which gave Welles a lot of practice grappling with a particular problem: fitting stories into a rigid running time, a fundamental problem also faced by the filmmaker. With Kane, Francois Truffaut notes, Welles placed

. . . three pints of liquid in a two-pint bottle. . . In many films, the expositional scenes are too long, the “privileged” scenes too short, which winds up equalizing everything and leads to rhythmic monotony. . . Welles benefited from his experience as a radio storyteller, for he must have had to learn to differentiate sharply between expositional scenes (reduced to flashes of four to eight seconds) and genuine emotional scenes of three to four minutes. . . Thanks to this quasi-musical conception of dialogue, Citizen Kane “breathes” differently from most films.57

Figure 6.8 Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, 1948): medium tracking shot. De Sica returns to his faithful tracking shot to end the film, culminating in a moment where the father bursts into tears. Bruno takes his hand. Bazin writes, “The son returns to a father who has fallen from grace. He will love him henceforth as a human being, shame and all.”

Source: Copyright 1948 Ente Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche.

Welles’ radio experience provided him a clear understanding of pace and momentum, a trait Bazin would recognize and celebrate.

When Citizen Kane opened in Paris in July 1946 after a five-year delay because American films were banned during the Nazi occupation, Bazin was only 28 years old and had only been a film critic for two years. But the film forged a soulful connection between the two young men, because Bazin started his first book four years later in 1950 devoted to the work of Welles. Bazin acknowledges Kane as a story with a challenging structure and multiple points of view. And while these are not new innovations for the medium, it is the comprehensive application of these techniques throughout the story that Bazin finds original. The film’s most important technical innovation is, of course, deep focus – the use of a wide angle lens at an aperture that allows the area from the immediate foreground to the deepest background in the framing to remain in focus. Gregg Toland, the cameraman for Kane, had recently won an Academy award for cinematography on Wuthering Heights (Wyler, 1939), and had worked with the Mitchell camera company on their new, self-blimped (noise dampening) BNC camera.

Toland came in early on the production, and, in addition to deep focus, the film broke ground in a number of other ways including “ . . . long takes; the avoidance of conventional intercutting through such devices as multiplane compositions and camera movement; lighting that produces a high-contrast tonality; UFA-style expressionism in certain scenes; low angle camera setups made possible by muslin ceilings on the sets; and an array of striking visual devices, such as composite dissolves, extreme depth of field effects, and shooting directly into the lights.”58

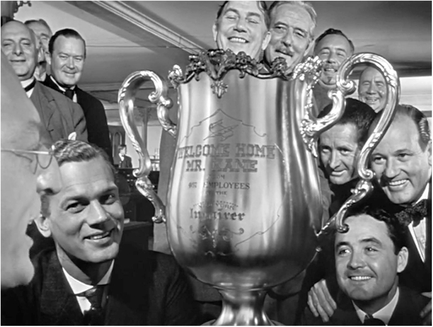

Toland credits coated lenses, faster film stocks (exposure index of 100 daylight) and arc lighting on floor stands for the look of the film, allowing him to shoot with a 24mm lens that when stopped down to f/11 or f/16 was essentially a “universal focus” lens. Deep focus was used throughout to simplify the coverage and capture “découpage in depth.” One such shot that Toland found remarkable was a close up of Mr. Bernstein (Everett H. Sloane)

. . .reading the inscription on a loving-cup [Figure 6.09]. Ordinarily, such a scene would be shown by intercutting the close-up of the man reading the inscription with an insert of the inscription itself, thereafter cutting back again to the close-up. As we shot it, the whole thing was compressed into a single composition. The man’s head filled one side of the frame; the loving-cup, the other. In this instance, the head was less than 16 inches from the camera while the cup was necessarily at arm’s length – a distance of several feet. . . Also, beyond this foreground were a group of men from 12 to 18 feet focal distance. These men are equally sharp.59

Toland said his collaboration on the film was aimed at fulfilling Welles’ instinctive grasp of the power of the camera to convey drama without words, for systematically breaking new ground using mise-en-scène and camerawork to tell a story without cutting.

Figure 6.9 Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941): deep focus. André Bazin greatly admired the work of Orson Welles, particularly the deep focus cinematography of Gregg Toland in Citizen Kane (1941). Toland singles out this shot as one of the deepest focus shots he created, with the focus carrying from Mr. Bernstein’s face (frame left) about 16” from the camera, to the loving cup at “arm’s length,” to the men in the deep background 12 to 18 feet away.

Source: Copyright 1941 RKO Radio Pictures.

Citizen Kane is by no means a conventional, run-of-the-mill movie. Its key-note is realism. As we worked together over the script and the final, pre-production planning, both Welles and I felt. . . the picture should be brought to the screen in such a way that the audience would feel it was looking at reality, rather than merely at a movie.

Closely interrelated with this concept were two perplexing cinetechnical problems. In the first place, the settings for this production were designed to play a definite role in the picture – one as vital as any player’s characterization. They were more than mere backgrounds: they helped trace the rise and fall of the central character.

Secondly – but by no means of secondary importance – was Welles’ concept of the visual flow the picture. He instinctively grasped a point which many other far more experienced directors and producers never comprehend: that the scenes and sequences should float together so smoothly that the audience would not be conscious of the mechanics of picture-making. . .

Therefore from the moment the production began to take shape in script form, everything was planned with reference to what the camera could bring to the eyes of the audience. Direct cuts, we felt were something that should be avoided whenever possible. Instead, we try to plan the action so that the camera could pan or dolly from one angle to another whenever this type of treatment was desirable. In other scenes, we preplanned our angles and compositions so that action which ordinarily would be shown in direct cuts be shown in a single, longer scene – often one in which important action might take place simultaneously in widely-separated points in extreme foreground and background.60

For Bazin, Kane marked an intelligent step forward in film realism, and he felt the impact of these techniques on the viewer was revolutionary. Rejecting analytical editing for camerawork that presents the entire dramatic field with equal clarity, the viewer is “forced to discern, as in a sort of parallelepiped of reality with the screen as its cross-section, the dramatic spectrum proper to the scene.”61 Bazin is returning here to the notion of the screen as a “window,” a cross-section that reveals a space beyond. Bazin calls this space “parallelepiped” – a prism shaped from six parallelograms – to capture the feeling of the three-dimensional space represented in the image that “extends beyond” the cross-section/widow/screen as a kind of three-dimensional “spatial box” captured by the lens, of which the cross-section/widow/screen is one “face.”

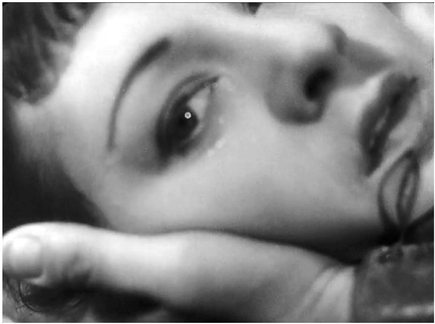

For Bazin, Susan Alexander’s (Dorothy Comingore) suicide attempt in Citizen Kane is a key scene that illustrates the congenital realism between the film image and the object reproduced, as well as the ability of a single shot to incorporate the principles of analytical editing. See Critical Commons, “Citizen Kane: Susan’s suicide as découpage in depth.”62 Bazin focuses not only on the staging in depth of the shot (Figure 6.10), but also the sound usage:

The screen opens on Susan’s bedroom seen from behind the night table. In close-up, wedged against the camera, is an enormous glass, taking up almost a quarter of the image, along with a little spoon and an open medicine bottle. The glass almost entirely conceals Susan’s bed, enclosed in a shadowy zone from which only a faint sound of labored breathing escapes, like that of a drugged sleeper. The bedroom is empty; far away in the background of this private desert is the door, rendered even more distant by the lens’ false perspectives, and, behind the door a knocking. Without having seen anything but a glass and heard two noises, on two different sound planes, we have immediately grasped the situation: Susan has locked herself in her room to try to kill herself; Kane is trying to get in. The scene’s dramatic structure is basically founded on the distinction between the two sound planes: Susan’s breathing, and from behind the door her husband’s knocking. A tension is established between these two poles, which are kept a distance from each other by the deep focus. Now the knocks become louder; Kane is trying to force the door with his shoulder; he succeeds. We see him appear, tiny, framed in the doorway, and then rush towards us. This spark has been ignited between the two dramatic poles of the image. The scene is over.63

Figure 6.10 Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941): in camera double exposure. Bazin praised this deep focus scene from Kane where Susan attempts suicide, but the shot is not made with traditional “deep focus” techniques but actually made as a special effects shot created in camera. We can see that this scene is “faked” because the focus is split – foreground and background in sharp focus, but the middleground in soft focus, which is not possible with a single take where the depth of field would be continuous from near to far.

The shot is impactful, as the audience actively struggles at first to decode the image, then begins to synthesize the meaning between the “two dramatic poles” as it unfolds. Bazin argues that the real revolution in this type of sequence shot is that is asks the viewer to actively participate in creating the meaning of the scene, to distinguish “the implicit relations, which the découpage no longer displays on the screen like the pieces of a dismantled engine.”64

However, in this scene, it turns out that Bazin’s faith in the ontological relationship of the image to reality is somewhat misguided, because the shot is not made with traditional “deep focus” but actually made as a special effects shot created in camera.

The process is not complicated, but is risky in the sense that the final effect cannot be previewed (since it is shot with a film camera) and if the effect is not properly aligned in the camera, it will have to be reshot. First, the camera is locked in place so that it is immobilized and the starting footage mark noted. Then the foreground composition – water glass and pills – is photographed first, with the focus set close, the foreground lit and background in total darkness. Then, with the lens capped, the film is run backwards to the starting position, and the lighting reversed: the foreground is left in total darkness and the background lit. With the focus reset to the deep background, the scene is re-photographed with Susan breathing deeply and Kane breaking down the door. What tells the audience that this scene is “faked” is that the focus is split – foreground and background in sharp focus, but the middleground is in soft focus, which is not possible with a single take where the depth of field would be continuous from near to far.65

For the time period, Bazin’s mistake is understandable since the film image was infrequently manipulated to this degree, and when it was, the effect was often visible, even without the technology for repeatedly viewing and studying a shot or a sequence. Though special effects imagery had existed since the early days of photography, and the digital tools for photo realistic image manipulation that simulates reality were decades in the future, most of the contemporary image compositing techniques like matte painting and miniature projection that Bazin might have encountered did not efface the means of their production very well. In short, trick shots in Bazin’s day were fairly obvious. But Kane was innovative for its day because of its extensive use the optical printer developed by Linwood Dunn at RKO, a device he eventually patented and sold in Hollywood under the Acme-Dunn brand of optical printers. In the hands of Dunn, the printer allowed very precise image compositing, with the caveat that more complicated shots required duplicating the footage in steps that built up grain and contrast, depending on the number of duplications required. Toland was resistant to new technology, which explains why he created the suicide shot in camera. Other “deep focus” shots were created optically: Raymond (Paul Stewart) looking at Kane in the distance moments after Susan Alexander has left him for good at Xanadu. Here the foreground is a prop door with Raymond looking through, the middle ground is a matte painting with Kane’s reflection rendered on the floor, and the image of Kane a miniature printed into that composition (Figure 6.11). This shot was created because Welles and Toland liked the feeling of depth that an earlier shot of Bernstein standing in a distant doorway had created, but there was no set built for the Xanadu shot; Dunn’s optical printer work solved the problem.66

Figure 6.11 Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941): miniature projection. Kane was innovative for its day because of its extensive use of the optical printer developed by Linwood Dunn. This “deep focus” shot was created optically: the foreground is a prop door, the middle ground is a matte painting with Kane’s reflection on the floor, and the image of Kane a miniature projection printed into that composition.

Source: Copyright 1941 RKO Radio Pictures.

It is a solution that Bazin might have praised, had he known about it, because in another instance he did praise the creation of spaces specifically for the camera. For The Grand Illusion (1937), French director Jean Renoir had moveable, partial sets built on location in the courtyard of a real barracks, rather than move into the studio, so that he could stage scenes with actors “inside” while the camera captured soldiers training through the set’s “window” in the background. Bazin writes, “It is through such techniques that Renoir attempts to portray realistically the relations between men and the world in which they find themselves.”67

A few observations about the suicide scene may clarify how it qualifies or does not quality as a counterexample to the realism of a deep focus shot. First, if we consider camera tricks or optical printing as a kind of “pseudorealism” on par with perspective in painting, we can try to unpack how Bazin would think about this shot, had he known how it was created. Bazin’s criticism of perspective as a form of pseudorealism in image creation is a question of balance: he chides those works of art that aim for the mere pseudorealism of faithful reproduction over the symbolic expression of a spiritual reality.68 Thus, to the extent that the suicide image aims at symbolic (or thematic) expression, its pseudorealism can be accepted: in so far as the image serves to express the depths of Susan’s despair at her domination by Kane, and the ego needs of Kane himself, its constructed nature can still be valued. This is consistent with what we know about Bazin’s theorizing, since he was more practical than pure, and saw deep focus as an important, not exclusive, aesthetic value that could interact with other value cinematic resources like lighting, editing and sound. For example, he accepted the more flamboyant moments in the film – Hollywood montage (Susan’s career montage) and flaunted temporal ellipsis (the breakfast scene) – because in his view, deep focus gives these moments a point of reference: “It is only an increased realism of the image that can support the abstraction of montage.”69 If the film is grounded in realism, then other methods are allowed.

Second, Bazin’s concern that perspective is pseudorealism addresses painting and drawing, where the technique is visible. Perspective in painting is a deceit that fools the eye, a construct that “will never have the irrational power of the photograph to bear away our faith. . . The fact that a human hand intervened [in a painting] cast a shadow of doubt over the image.”70 Presumably, all of these shortcomings of pseudo realistic perspective are erased if the viewer is unaware that a human hand intervened. One need only look at contemporary hyperrealism in painting and drawing, techniques that make the images indistinguishable from photographs, to understand that there is no “shadow of doubt” cast over these images: one is either fooled into thinking they are photographic images and accepts them as indexically linked to the reality they portray, or one is in on the ruse and marvels at how the artist has mimicked the aesthetic of the photograph. Similarly, Susan’s suicide is either regarded as indexically linked to the event or marveled at as a cinematic trick that mimics deep focus. This argument is underscored by Michael Betancourt in Beyond Spatial Montage, when he writes

Contra Bazin, it is not a presumed ontological relationship preserved by the long take but rather the appearance of such that is the significant element allowing the long take to seemingly present “reality” on screen beyond spatial montage. . . The aesthetic demand that Bazin makes is. . . one grounded in the belief that what appears on screen should be indexically linked to what would be visible if it were not cinema but actuality that was on view. It is not a denial of the constructed nature of cinema but a demand that cinema not appear to be constructed.71

In short, Bazin does not prohibit us from drawing on our experience with deep focus shots to engage the illusion created by Toland in the suicide shot. Given that it will never be as self evident as shot-reverse shot, and that it balances the pseudo-realism of the in camera composite shot with the thematic, symbolic needs of the scene, its semblance of deep focus is sufficient to transfer “reality” to it, and thus it is valued under Bazin’s theory. And besides, it was good enough to fool Bazin’s own eyes.

Bazin on Welles and The Magnificent Ambersons

Welles’ next film after Kane was The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles, 1942) a film based on the Pulitzer-prize winning novel by Booth Tarkington that Welles had previous adapted to radio. Bazin argues that, even though Gregg Toland’s “rugged frankness” was replaced by cinematographer Stanley Cortez’s “sophisticated elegance” on Ambersons, the foundational principles of both films – deep focus that holds the actors within the mise-en-scène, coupled with long takes that allow the dramatic flow of a scene to be an undivided unit – are maintained.72 A critical scene Bazin cites that demonstrates this foundational principle is a kitchen conversation between George (Tim Holt) and his aunt Fanny (Agnes Morehead).

The intricacies of the family ties in Ambersons are many, but in this scene, the privileged son George has just returned from a trip to Europe with his recently widowed mother, Isabel (Dolores Costello). George is trying to prevent his mother’s childhood flame, Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten), who has moved back to town after a 20-year absence, from proposing to her. Isabel’s spinster sister Fanny has secretly been in love with Eugene for decades, so she has been feeling anxious, hoping that the rekindled romance between her sister Isabel and Eugene will fail. See Critical Commons, “Magnificent Ambersons: Kitchen Scene as Découpage In Depth.”73 In the scene, George comes on a stormy night into the kitchen, where his Aunt Fanny has made him strawberry shortcake. George is aware that Fanny has feelings for Eugene, but Fanny tries to feign indifference while she tries to find out if Eugene accompanied them to Europe. The pretext drags out for a while until she finds out that he did not go to Europe, but did travel back from the East coast with them on the train. If that were not bad enough, Uncle Jack (Ray Collins), who has just wandered in on the discussion, begins to taunt her that Eugene is “dressing up more lately” and she should “ . . . be a little encouraging when a prized bachelor begins to tell you by his haberdashery what he wants you to think about him.” George continues to devour shortcake, and joins in the teasing, saying he would not be surprised if Eugene would soon be asking him for Fanny’s hand in marriage. Fanny finally bursts into tears and runs from the room, as they plead that they were “only teasing.”

Bazin points out that the strawberry shortcake is the “pretext action,” while finding out about Eugene, Fanny’s obsession is the “real action” underlying the scene. He compares Welles’s approach – filming the entire scene in a single four and a half minute long take, using deep focus – to the traditional Hollywood continuity approach.

Treated in the classic matter, this scene would have been cut into a number of separate shots, in order to enable us to distinguish clearly between the real and the apparent action. The few words that reveal Fanny’s feelings would have been underlined by a close-up, which would also have allowed us to appreciate Agnes Morehead’s performance at that precise moment. In short, the dramatic continuity would have been the exact opposite of the weighty objectivity Welles imposes in order to bring us with maximum effect to Fannie’s final breakdown. . . The slightest camera movement, or a close-up to cue us in on the scene’s evolution, would have broken this heavy spell which forces us to participate intimately in the action. . . It is obvious that this shot was the only one that allows the action to be set in such relief. If one wished to play each moment on the unity of the scene’s significance, and construct the action not on a logical analysis of the relations between the characters and their surroundings, but on the physical perception of these relations as dramatic forces, to make us present at their evolution right up to the moment when the entire scene explodes beneath this accumulated pressure, it was essential for the borders of the screen to be able to reveal the scene’s totality.74

After Fanny’s outburst, the scene continues for another full minute, with the reverberations of the outburst still echoing in the darkened kitchen. The men feel some remorse, but try to shift the blame for their cruelty back on her. George sees the situation in monetary terms: “It’s getting so you can’t joke with her about anything anymore. It all began when we found out that father’s estate was all washed up and he didn’t leave anything. I thought she’d feel better when we turned over the insurance to her.” Uncle Fred’s remorse rings equally false, patriarchal, and desolate as he delivers his final lines with his eyes wistfully in the middle distance: “I think maybe we’ve been teasing her about the wrong things. Fanny hasn’t got much in her life. You know George, being an aunt isn’t the great career it sometimes seems to be. I really don’t know much of anything Fanny has got. Except her feeling about Eugene.” The melancholy end of this scene is punctuated with a fade.