5 Eisenstein and Montage

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein (1898–1948) was the only son of a Jewish architect from Riga, and a mother who came from a well to do merchant family that was Russian Orthodox. The boy’s early family life was troubled by the authoritarian rule of his father, and he moved with his mother to St. Petersburg in 1905. His father joined them there in 1910, and his mother moved to Paris shortly thereafter, leaving Sergei in the care of his father. Eisenstein tried to follow in his father’s footsteps, studying civil engineering, but the 1917 Russian Revolution cut short his studies. He was drafted and sent to the front, and in 1918 he joined the Red Army while his father was allied with the White Guard, the anti-communist forces. An avid artist, Eisenstein drew continuously throughout his life, and his longstanding interest in the circus led him to a unit in the army that would stage plays and skits on the battlefront.

Mustered out of the army in 1920, he studied Japanese for a while before abandoning formal education for the Proletkult Central Workers Theatre. While working in this avant-garde theatre, Eisenstein studied under Vsevolod Meyerhold, a director of innovative, experimental drama, and an immensely influential figure in modern theatre. One of Eisenstein’s early works was a production of the play Gas Masks, staged in the Moscow Gasworks using the working turbines and catwalks of the complex as the setting for the action. In 1924, he suggested to Proletkult that they make a seven-part film series of agitation-propaganda films to glorify the revolution, and he launched into direction of his first feature, Strike with very little film experience but with the help of Edward Tisse, a military newsreel cameraman who would become his lifelong collaborator and cinematographer. Strike examined the steps leading to the political awakening of a factory, using broadly drawn characters and masses of workers to enact a heroic uprising that ends with an extreme close up of a pair of eyes glaring at the audience coupled with the title, “Proletarians, remember!”

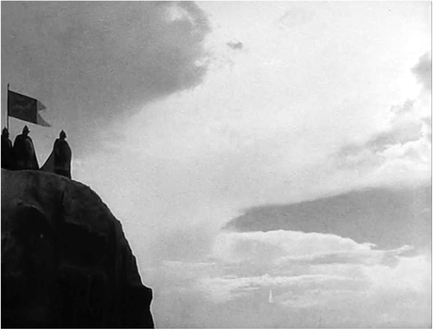

The next year, 1925, Eisenstein completed Battleship Potemkin, a remarkable, internationally recognized film, that was both celebrated and sharply contested in Germany, France, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. The film brought unprecedented profits for the Soviet film industry, and its reach extended as far as Hollywood where the powerful producer David O. Selznick declared it “unquestionably one of the greatest motion pictures of all time” and encouraged MGM to hire the director.1 Eisenstein was only 27 years old at the time, and Potemkin was a sensation, bringing the revolutionary fervor of his stage work to cinema, along with mass spectacle, intense screen violence never before seen, and a radically different style of editing. Along with the film, Eisenstein began to create a new theory of montage that explained how cinema could agitate the masses into political consciousness.

With only two films to his credit, Eisenstein was now world famous, at the center of Soviet filmmaking, and engaged in a community of young, emerging film artists, who worked in the state owned film industry bent on expanding the message of the Russian Revolution to mobilize mass action. In the vortex of revolutionary changes in social, political and artistic expression, Eisenstein would struggle his entire life to create imaginative works in a film, and to theorize their construction, while negotiating the prevailing political winds of a state enterprise operating under Soviet dictatorship. Theorizing about practical methods for creating impactful films was central to Eisenstein’s creative practice: he was as influential as a film theorist as he was a filmmaker. He was profoundly affected by Constructivism, a modern art movement that embraced abstraction, rejected the past, and sought to pare the work down to its essential elements. Constructivism advocated the creation of art that had the quality of factura, meaning the surface of the object should demonstrate how it had been made. In theatre, this meant that a creation for the stage should make its methods of production explicit. Constructivism was part of a larger trend in Soviet culture as a whole toward “techné-centered thought. Techné is Aristotle’s term for the unity of theory and practice within skilled activity.”2 In his view, the craftsperson should seek to master not only techniques, but also the standardized knowledge underlying them. Likewise, Soviet filmmakers, in the spirit of the times, sought to fully explore and understand the creative means available to them. Given Eisenstein’s international prominence, he was at the center of that enterprise, and both his creative film work and his dogged pursuit of the theoretical principles underlying them led to groundbreaking innovations in cinema.

At the same time, Eisenstein was largely a self-taught artist, a ravenous reader, and a prolific writer. His written work is wide open, overwrought and telegraphic, leaping from one topic to the next. His writing reflects a commitment to conflict and montage as much as his films do, and he tries to impress the reader with the connections he makes to other art forms and other cultures (i.e., music, kabuki theatre, haiku, etc.). Eisenstein is constantly remodeling old concepts and inventing new ones, “which are themselves transformed or ‘outgrown.’ Eisenstein himself rather aptly dubbed this aspect of his work a ‘theoretical self-service cafeteria.’”3 And while his theories explain film phenomena on the macro and the micro scale in intuitive and descriptive ways that perhaps only an accomplished film artist could, they often do not bear the weight of close scrutiny. His terminology is often vague or left undefined, and its use is undisciplined, so the reader is often left to ponder what exactly Eisenstein is referring to. In other instances, like Eisenstein’s famous chart of “vertical montage” in Alexander Nevsky (see p. 191), scholars have dismissed his theories as “heavy artillery to shoot sparrows.”4 His work has resisted neat unification, and he has been called “an unsystematic autodidact, a modern Leonardo da Vinci, a materialist in the grips of mysticism and conversely a Mystic in the grip of materialism, A neo-formalist, a semiotician, compliant propagandist, and an artist driven by an unresolved Oedipal complex.”5 To understand the editing theory of Sergei Eisenstein, and the work that engenders it, we will first look to the theories of his Russian contemporaries for context, clarify a few meanings of the word “montage,” examine Eisenstein’s early theories on how montage works to “seize the spectator,” and finally review the typology of montage that he proposed for understanding how editing functions in cinema.

Eisenstein's Contemporaries

Like Eisenstein, the most prominent filmmakers in the emerging Soviet cinema were very young: when Potemkin was released in 1925, three of the most significant were Dzia Vertov at 29, Lev Kuleshov, only 26 and Vsevolod Pudovkin who was 32. And while the left avant-garde was never a particularly unified movement,

the new Soviet Cinema offered the welcome spectacle of an art of the machine age belatedly shaking off its early subservience to nineteenth-century popular entertainment values. . . Cinema as a new mode of vision, a new means of social representation, a new definition of popular art, embodying new relations of production and consumption – all these aspirations found confirmation in the films and declarations of Eisenstein, Pudovkin and Vertov.6

If we focus for a moment on three of Eisenstein’s contemporaries – Vertov, Kuleshov and Pudovkin – we can better understand how Soviet cinema of the 1920s was a remarkable attempt to transform a popular art form, rapidly consolidating in Hollywood, into “a new mode of vision.”

Dziga Vertov (1896–1954)

Born David Abelevich Kaufman into a Jewish family in Poland in 1896, he changed his name into the more Russian Denis Arkadievich, and ultimately into “Dziga Vertov,” an avant-garde moniker that loosely translates from Ukranian as “spinning top” or “spinning gypsy.” In spring 1918 Vertov joined the Moscow Cinema Committee, and worked as a cameraman on weekly newsreels designed to highlight the achievements of the Soviet government. By 1919, he met Elizaveta Svilova, who worked with the Moscow committee as an editor. Svilova was willing to edit his films to include the innovations he was seeking, and within a short time they were married. She edited every film he made from that point forward. The couple pursued a new newsreel series, Cine-Pravda (literally, Cine-Truth) with the help of Vertov’s brother Mikhail Kaufman. Vertov quickly discovered the power of nonfiction motion picture propaganda to awaken the masses. This approach was consistent with the politics of the age in which Bolshevik journalism placed the newspaper at the center of motivating the masses. Lenin wrote: “A newspaper is not only a collective propagandist and a collective agitator, it is also a collective organizer.”7 Falling under many of the same influences as Eisenstein and Kuleshov, Vertov explored the formalist techniques consistent with the experimental milieu in which he came of age – slow motion, fast motion, double exposure, freeze frame, canted angles, superimposition, comparison by cutting, fastening the camera to cars and trains for tracking shots etc. – anything that would increase the impact of nonfiction motion pictures on Soviet audiences. While he condemned the study of aesthetics, he was writing provocative manifestoes about the power of the Kino-eye, the more perfect vision of the motion picture camera,

more perfect than the human eye, for the exploration of the chaos of visual phenomena that fill space. The kino-eye lives and moves in time and space; it gathers and records impressions in a manner wholly different from that of the human eye. . . Until now, we have violated the movie camera and forced it to copy the work of our eye. And the better the copy, the better the shooting was thought to be. Starting today we are liberating the camera and making it work in the opposite direction – away from copying.8

Vertov aimed to capture “film truth” by organizing elements of reality into films that reveal a deeper truth unseen by the human eye. His greatest works combine un-staged footage ingeniously, with tremendous rhetorical force, distilling “the sensibilities of newspaper column and Futurist poem into nonfiction feature films of incredible power and sophistication.”9 Vertov’s body of work had significant impact on the development of realism and nonfiction films during the 1920s, and his most famous feature film, The Man with a Movie Camera (1929) exhibits the creative genius of Svilova’s editing, particularly in the accelerated editing sequence that ends the film. See Critical Commons, “Editing Rhythm in The Man with a Movie Camera.”10

Vertov’s work continued to influence the documentary into the 1960s. His goal of revealing the truth underlying brute reality with improvisational camerawork greatly influenced the emergence of cinéma vérité, led by the French anthropologist Jean Rouch, and the direct cinema movement of Albert and David Maysles, Richard Leacock and D. A. Pennebaker in the United States.

Lev Kuleshov (1899–1970)

In a career that spanned 50 years, Lev Kuleshov (1899–1970) was a groundbreaking director, film theorist, and professor at V.G.I.K. one of the oldest film schools in the world, established in Moscow in 1919.11 The feature films of Lev Kuleshov are rarely seen in the West, but many of Russia’s most prominent directors trained under him, including Pudovkin, Eisenstein, Kalatozov and Parajanov. In his earliest writing about cinema he argued for a new, heroic style of filmmaking to replace the stultifying work coming from the budding Russian film industry. Kuleshov began to write and experiment with problems of acting and shot sequencing, and he sought to reduce film to its most basic material element, arriving at editing as the formal element specific to cinema. Though he directed 19 silent and sound feature films, many of which were nuanced psychological dramas, and wrote several significant books on filmmaking, he is known for his experiments in editing, particularly for what has become known as the “Kuleshov effect.”

Working with only rudimentary resources – some of his editing experiments were shot in 1921 on 90 meters (roughly 3.5 minutes) of 35mm film12 – Kuleshov began

to consider whether, under the powerful influence of montage, the spectator perceives an intentionally created Gestalt in which the relationship of shot to shot overrides the finer aspects of any actor’s performance. The famous “Kuleshov effect” with the Russian actor Mozhukin [also know as Ivan Mosjoukine] affirmed the speculation. Having found a long take in close up of Mozhukin’s expressionlessly neutral face, Kuleshov intercut it with various shots, the exact content of which he himself forgot in later years – shots, according to Pudovkin, of a bowl of steaming soup, a woman in a coffin, and a child playing with a toy bear – and projected these to an audience which marveled at the sensitivity of the actor’s range.13

Pudovkin went on to say that the audience “raved about the acting. . . the heavy pensiveness of his mood over the forgotten soup, . . . the deep sorrow with which he looked on the dead child, . . . the lust with which he observed the woman. But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same.”14 Although the film does not survive intact, the impact of this experiment has been pervasive, suggesting that juxtaposition is a powerful creator of meaning. It has been studied and written about in countless texts, including a 1964 CBS television interview with Alfred Hitchcock. See Critical Commons, “A Talk with Hitchcock (1964) – Hitchcock Explains the Kuleshov Effect” and a reconstruction of the film The Kuleshov Effect.15

Beyond this experiment, Kuleshov is also remembered for experiments in “artificial landscapes” (now commonly called creative geography) in which a sequence containing shots of actors walking in disparate areas of Moscow ends with a two shot of them converging, an early demonstration that motion vectors in film (to use Herbert Zettl’s terminology) are key to building and stabilizing the viewer’s spatial orientation, (see Chapter 1, p. 24). Creative geography is further demonstrated in a Kuleshov sequence of actors walking up steps of a Moscow landmark, conjoined with a stock shot of the White House in Washington, D.C., creating a unique, unified screen space from distinct real spaces. In another instance, Kuleshov synthesized a film of a woman moving by cutting together shots of the feet, heads and hands of different women. Kuleshov went on to publish three significant books of film theory and practice, and, despite coming under attack in the Stalin era, was appointed in 1944 to Head of the All-Russian Institute of Cinematography (V.G.I.K.), received the nation’s highest award, the Order of Lenin in 1967, and continued to lecture on filmmaking until very late in his life.

Vsevolod I. Pudovkin (1893–1953)

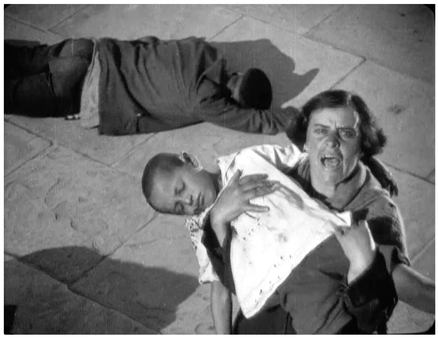

An engineering student in Moscow, Pudovkin served in the artillery during World War I. He was captured by the Germans, spent three years in prison, was released and returned to the city in 1918. He entered V.G.I.K. in 1920 and studied under Kuleshov, leaving in 1923 to join Kuleshov’s Experimental Laboratory. One of his first successful features, Mother (1926) was drawn from the Maxim Gorky novel, and became a classic film of the Russian silent period.

Set in the Russian Revolution of 1905, a vast movement of peasant unrest, worker’s strikes and mutinies in the armed forces, The Mother (Vera Baranovskaya) is caught between The Father (Aleksandr Chistyakov) and The Son (Nikolai Batalov) who are on opposite sides of a factory strike. After The Father is killed in the strike, The Mother’s actions inadvertently send her son to prison. With her political consciousness transformed, she joins a march to free the strikers, who, learning of the approaching march, plan to escape. The Son is shot during the escape, and at the end of the film, The Mother is trampled to death by the Tsarist cavalry.

Pudovkin believed that a central problem for the film artist is to find a way to reveal emotions visually. He writes,

The scenario-writer must bear always in mind the fact that every sentence that he writes will have to appear plastically upon the screen in some visible form. Consequently, it is not the words he writes that are important, but the externally expressed plastic images that he describes in these words.16

Plastic material is perhaps more commonly known as the objective correlative, a term coined in 1922 by T. S. Eliot who argues that “The only way of expressing emotion in the form of art is by finding an objective correlative; in other words, a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion.”17 Pudovkin argues that incorporating plastic material in film allows the actors to tone down their performances, to underplay what would be more broadly rendered on the stage because the director, through montage, is able to associate the actor’s performance with powerful, expressive imagery that will help carry the scene.

After The Father is killed early in Mother, Pudovkin creates a long, somber evening scene of The Mother “sitting with the dead,” as her husband lies in on a bier in their home. See Critical Commons, “Mother (Pudovkin, 1926) The Objective Correlative: Water Dripping.”18 The pace of the cutting is very slow and methodical, and the movements of the actors are subdued, and almost motionless. The sequence proceeds as follows:

- A somber two shot in the family home of the mother, sitting in grief adjacent to the deceased father who is lying on a bier. The mother sits stoically. (:07 seconds)

- Cut to a medium close up of a pan of water from a Russian “rukomoynik,” a kind of functional, industrial wall-mounted sink. The water drips slowly into the basin, creating a slow, metronomic beat. (:07 seconds)

- Cut to a medium close up of the mother, eyes distant, expressionless, staring straight into the camera. (:04 seconds)

- Cut to the medium shot of the father motionless on his bier. (:04 seconds)

- Cut to the medium close up (shot 2) of a slow drip into pan of water. (:07 seconds)

- Cut to a long shot, the son opens the door and enters. (:05 seconds)

- Cut to the somber two shot (shot 1) of mother by the bier. (:04 seconds)

- Cut to long shot of the son at door (shot 6), he stares while the door continues to slowly swing open behind him. (:08 seconds)

- Cut to the medium shot of the father (shot 4) motionless on his bier. (:03 seconds)

- Cut to the medium close up (shot 3) of the mother expressionless, staring straight into the camera. (:03 seconds)

- Cut to long shot of the son at door (shot 6), he stares and drops his hands to his side. (:05 seconds)

- Cut to the medium close up (shot 3) of the mother expressionless, staring straight into the camera. (:03 seconds)

- Cut to long shot of the son at door (shot 6), he crosses without taking his eyes off his parents, and sits slowly on the bed. (:07 seconds)

- Cut to the medium close up (shot 2) of a slow drip into pan of water. (:07 seconds)

- Cut to the medium close up (shot 3) of the mother expressionless, staring straight into the camera. (:03 seconds)

- Cut to long shot of the son on the bed (shot 6) and he finally speaks. (:03 seconds)

- Title card: “Who killed him?”

The Mother answers that one of his friends, a trouble making striker, killed his father, and Pudovkin returns for one more round of close ups, this time with tears in The Mother’s eyes, followed by the water dripping, before closing on The Father dead on the bier.

The shot selection, acting, and cutting here are all very restrained. The shot selection consists of five shots that are virtually static, except for The Son who slowly sits on the bed. The establishing two shot of Mother and deceased Father is used to open the scene, and to re-establish when The Son enters. At the bier, there are close ups of the expressionless Mother (shown seven times) and the motionless Father (shown four times, including the closing shot). At the door there is a long shot of The Son entering, staring, then sitting, and asking who killed his father (shown six times). Also at the door is a close up of the water dripping from the rukomoynik into the basin (shown four times).

The cycling of these shots is tactful, and the cutting rhythm is tranquil and detached. At the core of the scene is the repeated stasis of mother and father, widow and corpse, intercut with the dripping water that continues to mark the slow, inevitable passage of time, like the grains of sand through an hourglass. Visually, the dripping water is a precise choice for the objective correlative, suggesting at once, the monotony of a ticking clock, the loss of vital essence, the relentless forward motion of time, and the mother’s tears, which conclude the scene.19 The fusion of these elements synthesizes a feeling of grief, “the Hour of Lead,”20 to use a line from the famous Emily Dickenson poem.

Pudovkin returns to the use of plastic material throughout the film, creating plastic synthesis through montage:

[In] Mother, I try to affect the spectators, not by the psychological performances of an actor, but by plastic synthesis through editing. The son sits in prison. Suddenly, passed in to him surreptitiously, he receives a note that next day he is to be set free. The problem was the expression, filmically, of his joy. The photographing of a face lighting up with joy would have been flat and void of effect. I show, therefore, the nervous play of his hands and a big close-up of the lower half of his face, the corners of the smile. The shots I cut in with other and varied material – shots of a brook, swollen with the rapid flow of spring, of the play of sunlight broken on the water, birds splashing in the village pond, and finally a laughing child. By the junction of these components our expression of “prisoner’s joy” takes shape.21

See Critical Commons, “Mother (Pudovkin, 1926) The Objective Correlative: Spring.”22

Pudovkin Versus Eisenstein

Beyond his use of plastic material, it is instructive to compare Pudovkin’s concept of montage to Eisenstein’s. Like Kuleshov, Pudovkin sees editing as linkage, shots joined like links in the chain, a construction assembled “Screw by screw, brick by brick.”23 Eisenstein counters that this notion of editing is only a diluted version of the real source of editing’s power, conflict. In 1929, Eisenstein wrote a critique of Pudovkin’s view,

Before me lies a crumpled yellowing sheet of paper.

On it there is a mysterious note:

“Series – P” and “Collision – E.”

This is a material trace of the heated battle on the subject of montage between E (myself) and P (Pudovkin) six months ago.

We have already got into a habit: at regular intervals he comes to see me late at night and, behind closed doors, we wrangle over matters of principle.

So it is in this instance. A graduate of the Kuleshov school, he zealously defends the concept of montage as a series of fragments. In a chain. ‘Bricks.’ Bricks that expound an idea serially.

I opposed him with my view of montage as a collision, my view that the collision of two factors give rise to an idea.24

Eisenstein casts Pudovkin as a traditional director, whose use of montage remains grounded in Hollywood editing practices, particularly those gleaned from the films of D. W. Griffith, who was greatly admired by the Soviet filmmakers. Eisenstein sees Pudovkin’s films as conventionally rendered stories. While not as precisely driven by the character-centered causality that gives Hollywood films a more tightly focused narrative, they do present ordinary people, swept along by the movement of the masses, transformed by the impact of the revolutionary events around them. Not surprisingly, Pudovkin argues for the “invisible observer” model of film editing; that is, the cuts in a film mimic the shifts in attention of an ideal observer who controls the flow of narrative information. So a close-up shot mimics our visual fixation on details, and by this shifting focus, the director controls the “psychological guidance” of the viewer.

By contrast, in The Cinema of Eisenstein, David Bordwell gives a thorough account of the plotless cinema advanced by the more radical film artist Eisenstein, a style that

- rejects the notion of plot as a series of consequences developing from the actions of an individual

- favors perceptual and emotional shock over stringent realism

- depicts the “mass protagonist,” not the individual, as the creator of historic change, and so . . .

- unifies the film using acts and longer sequences that structure the stages of mass action

- creates motifs of significant objects and graphic patterns to develop complex, unifying thematic associations

- cultivates overlapping editing to create an agitated rhythm, and to replay key events

- employs typage, Eisenstein’s innovative portrayal of character through the external features of physiognomy, dress and behavior to indicate religion, region of origin, and class, particularly in the grotesque attributes of the bourgeois

- paints the broad sweep of history using associative parallels. Where Pudovkin kept these parallels within the diegesis (e.g., the militants’ march in Mother is compared with the ice thawing on a nearby river), Eisenstein moves beyond that to quasi-diegetic or non-diegetic parallels. (See intellectual montage below, p. 186.) Typically, non-diegetic material will be photographed against a black background in close up, providing “a kind of abstract commentary on the action, making the viewer aware of an intervening narration that can interrupt the action and point of thematic or pictorial associations.”25

So while both Pudovkin and Eisenstein hope to propagandize the proletariat, Pudovkin is clearly more traditional in film style and form, providing the customary “psychological guidance” for the viewer through editing, while Eisenstein is more inventive, relentlessly bent upon pushing the artistic capabilities of the medium. Pudovkin’s human scale stories are more conventional, while Eisenstein’s strive for a vibrant new filmic art that can glorify the monumental heroics of the masses.

Likewise, Pudovkin’s theoretical writings do not aim as high as Eisenstein’s. Pudovkin wrote two practical handbooks for makers: Film technique (1929) and Film acting (1933). Since they are exclusively grounded in the practice of making films, his accounts of how editing works draw heavily on what was known from the routines and practices of the day. Ordinary editing – what Pudovkin called “Structural Editing” – is the result of taking the shooting script and atomizing it: at the production stage, the filmmaker breaks the script down first into scenes, then into sequences, then into shots, and photographs that material. The resulting footage is assembled to reflect “the guidance of the attention of the spectator to different elements of the developing action in succession. . . [This] is, in general, characteristic of the film. It is the basic method.”26 (Note that découpage articulates the same concept. See p. 58.)

Beyond this basic method, Pudovkin described as early as 1926 a group of five elements of editing under the heading “Editing as an Instrument of Impression (Relational Editing).” He argues that these five are the primary “special editing methods having as their aim the impression of the spectator.”27 Again, the basic editing method is structural or constructive; relational editing is a subset of those methods that has special power to create impressions or associations in the viewer. Some of these five are more coherent and specific than others, but overall appear to be more committed to crosscutting than Eisenstein’s conception of montage is to creating metaphor or collision. In other words, his typology remains within a coherent scenario of integrated characters, whose temporal and spatial relationships are clearly indicated. Pudovkin never seems to be willing to push very far beyond the coherent diegesis, even with these “special editing methods” which he differentiates as follows:

Contrast

In practice, this method seems to be nothing more than crosscutting between opposing images. Pudovkin writes,

Suppose it be our task to tell of the miserable situation of a starving man; the story will impress the more vividly if associated with mention of the senseless gluttony of a well-to-do man. On just such a simple contrast relation is based the corresponding editing method. On the screen the impression of this contrast is yet increased, for it is possible not only to relate the starving sequence to the gluttony sequence, but also to relate separate scenes and even separate shots of scenes to one another, thus, as it were, forcing the spectator to compare the two actions all the time, one strengthening the other. The editing of contrast is one of the most effective, but also one of the commonest and most standardised of methods, and so care should be taken not to overdo it.28

The thrust here is to place opposites against each other in a sequence, but unlike the idea-associative collision montage or intellectual montage (see below p. 186) where the forward motion of an action on screen is stopped by radially colliding visuals, Pudovkin here is calling for a kind of pointed crosscutting – “to relate separate scenes and even separate shots of scenes to one another” – not the radical departure Eisenstein seeks.

Parallelism

Pudovkin uses the term parallelism, but it is not clear that his intended meaning for the word is the standard usage of film studies. The example he gives is a sequence in which

a working man, one of the leaders of a strike, is condemned to death; the execution is fixed for 5 a.m. The sequence is edited thus: a factory-owner, employer of the condemned man, is leaving a restaurant drunk, he looks at his wrist-watch: 4 o’clock. The accused is shown – he is being made ready to be led out. Again the manufacturer, he rings a door-bell to ask the time: 4:30. The prison wagon drives along the street under heavy guard. The maid who opens the door – the wife of the condemned – is subjected to a sudden senseless assault. The drunken factory-owner snores on a bed, his leg with trouser-end upturned, his hand hanging down with wristwatch visible, the hands of the watch crawl slowly to 5 o’clock. The workman is being hanged. In this instance two thematically unconnected incidents develop in parallel by means of the watch that tells of the approaching execution. The watch on the wrist of the callous brute, as it were connects him with the chief protagonist of the approaching tragic denouement, thus ever present in the consciousness of the spectator.29

Pudovkin’s parallelism seems like a combination of motif (the clock/time motif), crosscutting (simultaneous actions) and contrast editing (worker vs. factory owner). Traditional usage, according to Kristen Thompson, defines crosscutting as “editing which moves between simultaneous events in widely separated locales. ‘Parallel editing’ differs in that the two events intercut are not simultaneous” and if the time relationship is unclear, the device could be either.30

Symbolism

What Pudovkin calls “symbolism” is more commonly called idea associative comparison montage or visual metaphor. (See below, p. 158.) Writing of Eisenstein’s Strike (1925) Pudovkin says, “just as a butcher fells a bull with the swing of a pole-axe, so cruelly and in cold blood, were shot down the workers. This method is especially interesting because, by means of editing, it introduces an abstract concept into the consciousness of the spectator without use of a title.”31 The strikers are slaughtered cattle, and juxtaposition creates this “symbol” or visual metaphor.

Simultaneity

Known in American films since 1910, Pudovkin is referring to what is commonly known as crosscutting, when two simultaneous actions that are spatially distant are intercut. (See crosscutting, Chapter 2, p. 75.) Pudovkin writes that this ubiquitous device is aimed at suspense:

The whole aim of this method is to create in the spectator a maximum tension of excitement by the constant forcing of a question, such as, in this case: Will they be in time? –will they be in time? The method is a purely emotional one, and nowadays overdone almost to the point of boredom, but it cannot be denied that of all the methods of constructing the end hitherto devised it is the most effective.32

Leit-motif (reiteration of theme)

The German leitmotiv literally means “leading motif” or “guiding motif,” and was first used to describe Wagner’s association of short, distinctive musical phrases with a particular character, ideas, or situations in his operas. Here, Pudvokin simply means repetition for emphasis of theme, and gives this example: “In an anti-religious scenario that aimed at exposing the cruelty and hypocrisy of the Church in employ of the Tsarist regime, the same shot was several times repeated: a church-bell slowly ringing and, superimposed on it, the title: ‘The sound of bells sends into the world a message of patience and love.’ This piece appeared whenever the scenarist desired to emphasise the stupidity of patience, or the hypocrisy of the love thus preached.”33 Clearly, since Pudovkin is writing in the silent era, a leit-motif need not use sound or a super imposed title, though a musical accompaniment to a silent exhibition in a theatre may have used bells. Pudovkin is merely pointing to repetition as a way to reinforce meaning: the leit-motif could be audio or video.

Though Pudovkin’s film work is of secondary importance to Eisenstein’s, and indeed has been called “the work of a blackboard theoretician. . . [who] used images in an invariably dull way – the photographed storyboard,”34 he had a significant impact in the Soviet film industry. As a director of 27 films, as a screenwriter, actor, author of early books on film theory and as a film teacher at V.G.I.K., Pudovkin played a very important role in the development of Russian cinema. Eisenstein would always outshine Pudovkin, particularly in the West. Eisenstein’s films were more innovative in their editing, more sensational in their violent clashes, more energizing in their nervous rhythm, and more heroic in scale than Pudovkin’s work. We will survey Eisenstein’s key contributions to Russian cinema after we first clarify a number of distinct meanings for the word “montage.”

What is "Montage"?

Montage is a word that is frequently used to describe a range of filmic phenomena without ever specifying systematically all its uses. Montage in the broad sense describes a series of short shots that compress time, space, or narrative information, but it actually has several distinct meanings. Its association with Eisenstein is often condensed – too simply – into two words: “collision montage,” whereby the juxtaposition of two shots that oppose each other on formal parameters or on the content of their images are cut against each other to create a new meaning not contained in the respective shots: shot A + shot B = new meaning C.

The association of collision montage with Eisenstein is not surprising. He consistently maintained that the mind functions dialectically, in the Hegelian sense, that the contradiction between opposing ideas (thesis versus antithesis) is resolved by a higher truth, synthesis. He argued that conflict was the basis of all art, and never failed to see montage in other cultures. For example, he saw montage as a guiding principle in the construction of “Japanese hieroglyphics in which two independent ideographic characters (‘shots’) are juxtaposed and explode into a concept. Thus:

- Eye + Water = Crying

- Door + Ear = Eavesdropping

- Child + Mouth = Screaming

- Mouth + Dog = Barking

- Mouth = Bird = Singing35

He also found montage in Japanese haiku, where short sense perceptions are juxtaposed, and synthesized into a new meaning, as in this example:

- A lonely crow

- On a leafless bough

- One autumn eve.

As Dudley Andrew notes, “The collision of attractions from line to line produces the unified psychological effect which is the hallmark of haiku and montage.”36 But there are at least six usages for the word “montage,” of which collision montage is just one, and it is worth clarifying some of those usages before we proceed.

Six Usages of the Word "Montage"

1. Montage = Editing

In many contexts, “montage” simply means “editing.” The French word “montage” means literally “a mounting,” “an assembly,” as in “mounting an engine,” and the English screen credit “Editor” has the French equivalent “le monteur/la monteuse.” This usage, editing as “mounting” is relevant to Eisenstein’s theory because he saw editing as the process whereby the simple assembly of shots, the “mounting” of the film shot by shot through editing, is a form of engineering, specifically “psycho engineering” whereby the assembled shots will create moments of raw stimulation, triggering basic emotions in the viewer that, over time, develop into larger themes.

2. Sequential Analytical Montage

Herbert Zettl defines this kind of montage as one that will “condense an event into key developmental elements and present these elements in their original cause-effect sequence.”37 While adhering to the ordinary forward progression of time, this type of montage routinely implies its central event or idea rather than show it explicitly. A car crash scene that intercuts the shots of two approaching cars without showing them hit, but includes the aftermath is one example given by Zettl for this type of montage. Eisenstein used this technique in Strike (1925). When Cossacks attack the workers in their living quarters, they drop a baby from a balcony. The horrifying montage ends with the baby lying on the ground, rather than showing the baby hit the ground. (Figure 5.1). See Critical Commons, “Kinds of Montage: Analytical Sequential Montage in Strike.”38

3. The Hollywood Montage

Figure 5.1 Sequential Analytical Montage in Strike. When Cossacks attack the workers in their living quarters in Strike, they drop a baby from a balcony. The horrifying montage ends with the baby lying on the ground, rather than showing the baby hit the ground. Herbert Zettl identifies this as an analytical sequential montage in which the main event is implied.

Source: Copyright 1925 Sovkino.

This familiar subset of the Sequential Analytical Montage, where key elements of the narrative are compressed, often uses traditional markers of time passing like dissolves, but also tropes like newspaper headlines. In Heaven Can Wait (Lubitsch, 1943) the aging socialite, Henry Van Cleve (Don Ameche), is lamenting growing older, and a humorous montage of birthdays passing, shown in cakes, candles, a telegram and an endless stream of birthday neckties summarizes the theme that getting older is not all that much fun. See Critical Commons, “Kinds of Montage: Hollywood Montage in Heaven Can Wait.”39

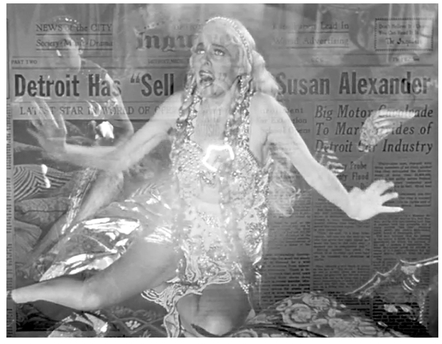

Another classic example of the Hollywood montage comes from Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941) where Susan’s disastrous opera career and her descent into an attempt at suicide is summarized with newspaper headlines and a flashing stage lamp that ultimately flickers out as the soundtrack winds down to a halt (Figure 5.2). Doug Travers at RKO created the montage. See Critical Commons, “Kinds of Montage: Hollywood Montage in Citizen Kane.”40

4. Sectional Analytical Montage

Figure 5.2 Hollywood montage in Citizen Kane. Susan Alexander’s disastrous opera career and her descent into a suicide attempt is summarized with a series of newspaper headlines, shots of her performance and a flashing stage lamp.

Source: Copyright 1941 RKO Radio Pictures.

Herbert Zettl uses this term for a montage that shows the various sections of an event and explores the complexity of a particular moment. Rather than showing cause and effect, a sectional analytic montage temporarily stops the progression of a screen event and explores an isolated point in time from various viewpoints.41 We can imagine such a montage in a film that halts the progress of the narrative to bring out the emotional content of a scene. Imagine two lovers strolling a sidewalk. In one case, we could interrupt story progression to create a montage that illustrates “Manhattan, 5:00 pm, late autumn as winter approaches.” In another case, with another shot of two lovers strolling on a sidewalk, we could interrupt story progression to create a montage that illustrates “Paris, 5:00 pm, early spring, as winter fades.” We can imagine the kinds of images that would be expressive in each case, and how the cutting of these images would impact the emotional tone of the lover’s interaction. (And it is worth noting that Zettl argues that a multiscreen presentation of this kind of imagery would be, by definition, a sectional analytical montage because the event details are presented simultaneously rather than sequentially.)

Another form of sectional analytical montage is one that portrays “subjective time” by temporarily arresting event progression to examine a specific moment. In Sam Peckipah’s The Wild Bunch (1969), Pike Bishop (William Holden) and his men try to force General Mapache to release one of their gang, Angel (Jaime Sánchez), who is barely alive after being tortured. When the general cuts his throat, the men gun Mapache down almost by instinct, in front of hundreds of his men. At that point, “time stops,” as they assess the hopelessness of their situation (Figure 5.3). Peckinpah stops the scene for roughly 30 seconds as the men react, looking at each other and the Mexican soldiers, taking in their situation and finally acknowledging their commitment and dedication to one another before the hopeless blood bath to come. See Critical Commons, “The Wild Bunch: Final Shootout,” for a sectional analytical montage near the beginning.42

5. Idea-Associative Comparison

This type of montage uses successive shots that appose similar themes in different events, so that the thematically related events reinforce each other.43 Here, by placing shots (or in Eisenstein’s terminology “fragments”) that are related thematically side by side, the viewer contemplates the similarity, and synthesizes a tertium quid, literally a “third thing,” that is not contained in either shot. The classic example for this case is from Eisenstein’s October: Ten Days that Shook the World (1928). Alexander Kerensky (Vladimir Popov), a member of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, is the Minster of Justice in the provisional government from the Winter Palace of Czar Nicholas II, who has been overthrown and executed with all his family. Kerensky is seeking democratic reforms but signs an order reinstating the death penalty for army deserters. In a segment that leads with the title card “A ‘Royal’ Democrat,” Eisenstein places shots of Kerensky in his formal dress uniform with leather boots and gloves (Figure 5.4) against a shot (“fragment”) of the mechanical peacock44 unfurling his feathers (Figure 5.5), suggesting that he is vain and strutting like a peacock, and corrupted by the power he has ascended to.

Figure 5.3 Sectional Analytical Montage in The Wild Bunch. In Peckipah’s The Wild Bunch, “time stops,” as members of the gang – outgunned in a standoff with the Mexican army – assess the hopelessness of their situation. Peckinpah stops the scene for roughly 30 seconds as the men react.

Source: Copyright 1969 Warner Bros.-Seven Arts.

Figure 5.4 October: idea associative comparison, Kerensky vs. peacock. Eisenstein intercuts shots of Alexander Kerensk, leader of the provisional government who occupies the former Czar Nicholas’ palace, against a shot of a mechanical peacock unfurling his feathers, suggesting that he is vain and corrupted by power.

Source: Copyright 1926 Goskino.

Figure 5.5 October: idea associative comparison, Kerensky vs. peacock.

Source: Copyright 1926 Goskino.

See Critical Commons, “Kinds of Montage: Idea Associative Comparison, Kerensky vs. Peacock”45

Another famous comparison montage from Eisenstein is found in Strike (1925) that intercuts non-diegetic shots (“fragments”) (i.e., images that are outside the story space of the film) of a bull being slaughtered with shots (“fragments”) of soldiers killing striking factory workers. The visual metaphor – the strikers are cattle and the soldiers are butchers – is clear and effective, and continues the animal motif that runs throughout the film: each of the spies for the police shown earlier is tagged visually as Fox, Owl, Bulldog or Monkey. See Critical Commons, “Visual Metaphor in Strike.”46 Notice that because the footage of the bull is non-diegetic and viscerally violent it is tempting to classify this as a idea-associative collision montage rather than idea associative comparison, but the fact that we can describe its meaning as “the strikers are cattle led to the slaughter” points to the comparison rather than the collision of these two.

6. Idea-Associative, Collision Montage

In a collision montage, two opposing events express or reinforce a basic idea or feeling.47 Here again, there is a tertium quid, a third something, generated from the placing the two events next to each other. But in this case the juxtaposition creates conflict, not comparison, and consequently tends to intensify the moment even more than a comparison montage. Given that it is an overtly rhetorical device, the collision montage has the potential to be impactful or alienating to an audience.

More than any other usage of the word “montage,” it is this “collision” usage that we associate with Eisenstein. In part, this association grows from the fame Eisenstein achieved with the editing of the Odessa steps sequence from Battleship Potemkin, probably the most famous sequence in film history, and a masterful piece of editing the likes of which had not been seen when the film premiered in 1925. Certainly the notion of “collision” corresponds to “intellectual montage,” a term from Eisenstein’s typology of montage that we will deal with more fully below. For now, we can point to the closing of the steps sequence as an example of collision montage. See Critical Commons, “Battleship Potemkin (1925) Odessa Steps,” to view the four closing shots.48

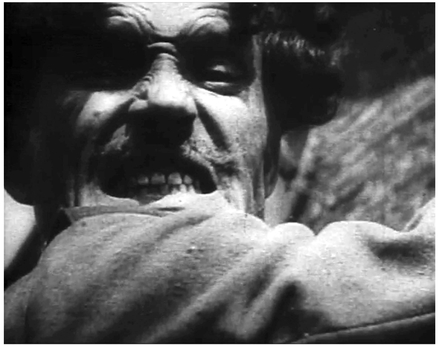

In the final four shots49, Eisenstein synthesizes the idea of “horrific, violent repression.” Starting from the final shot of the baby carriage beginning to flip over at the end of its journey down the steps (Figure 5.6), Eisenstein cuts to repeated actions of a Cossack slashing downward towards the camera, first in a medium close up (Figure 5.7), then in a tight close up (Figure 5.8) where he grimaces ferociously. Spatially, it is unclear where he is standing, and if he is slashing at the baby, since nothing in the sequence has shown their relative positions. The next shot – the school mistress with smashed pince-nez screaming with blood dripping down her face – only adds to horror and the spatial ambiguity: was she shot or was she slashed?

The explosive energy these four shots impart can be described in a number of ways, all of which demonstrate the difficulty in putting a highly kinetic image sequence into words, but also suggesting the range of formal parameters (attractions) embedded in the shot that potentially collide in the four shot sequence;

High angle shot (carriage tips), low angle shot (Cossack starts to strike), low angle shot (Cossack slashes once, and begins to slash again), head-on shot (woman with pince-nez is frozen in horror).

Objective medium shot (carriage tips), subjective shot (Cossack starts to strike towards us), subjective shot (Cossack slashes towards camera and begins to slash towards us again), objective medium shot (woman with pince-nez is frozen in horror).

Incomplete action (carriage tips), incomplete action (Cossack starts to slash), complete /incomplete action (Cossack slashes once, and begins to slash again), resolution (woman with pince-nez is frozen in horror).

Figure 5.6 Idea-associative, collision montage. In the final four shots of the Odessa steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin, Eisenstein synthesizes the idea of “horrific, violent repression.” Starting from the final shot of the baby carriage . . .

Source: Copyright 1925 Goskino.

Figure 5.7. . .Eisenstein cuts to overlapping action of a Cossack slashing downward towards the camera, first in a medium close up . . .

Source: Copyright 1925 Goskino.

Figure 5.8. . .then in a tight close up.

Source: Copyright 1925 Goskino.

Figure 5.9 Battleship Potemkin: the sequence ends with a tight close up of the woman in the pince-nez frozen in bloody horror.

Source: Copyright 1925 Goskino.

Forward energy down the stairs that does not resolve (carriage tips), forward energy down towards camera that does not resolve (Cossack starts to slash), forward energy down towards camera that resolves then does not resolve (Cossack slashes once, and begins to slash again), effect (woman with pince-nez is frozen in horror).

Regardless of how we try to account for the impact of the colliding attractions in each shot, their effect is palpable. They are clear evidence of Eisenstein’s artistry, and the correctness of his theorizing: his intuition that collision montage can be a visceral stimulus towards the “psycho engineering” is obvious here.

One final question: What about audio? We have not accounted for the interaction of audio and video in the categories above, and audio is a powerful element to juxtapose within a montage sequence. Zettl says that often audio can work as a montage element in a way that is effective but less glaring than a visual element, since both kinds of analytical montage – sectional and sequential – and ideas-associative montage – collision and comparison – emerge when the sequence is juxtaposed with a specific track.50 Zettl gives as an example of comparison idea-associative A/V montage a long shot of a sports car moving through tight turns juxtaposed with the sound of a jet engine of a fighter plane, which only hints at the potentials of audio in montage. Today, with advances in Dolby noise reduction and surround sound, the wide-ranging creative possibilities of audio as a crucial, combustive element in montage are unquestioned. But for Eisenstein, a famous filmmaker with Potemkin to his credit and his first sound film still 13 years ahead, the issue of how to integrate audio into his theory of montage is not a pressing one. More acute is the issue of how he will conceptualize montage, how he will catalog its formal potentials and account for its substantive impact on the viewer. His theorizing will progress in the silent period even though his filmmaking flounders politically, but ultimately he will return to the sound film as a creative and theoretical problem much later in his life.

Eisenstein's Early Theorizing: The Attraction and Seizing the Spectator

Eisenstein’s early theorizing about montage grew out of his work in theatre, which began when he served in the Red Army. In 1918, as the civil war in Russia deepened, he began painting posters for agit-prop trains that were presented as simple plays with broadly drawn political characters representing good and evil. “Agitation-propaganda” trains were units of the army that spread the Bolshevik message across the vast expanse of Russia. Since much of the population was illiterate, the trains travelled to remote regions without electricity to propagandize the peasantry. Mustered out of the army in 1920, Eisenstein joined the Proletkult movement in Moscow, an experimental artistic group dedicated to advancing a new working class aesthetic in the arts.

In 1921, Eisenstein came under the tutelage of Vsevolod Meyerhold, the leading Russian director of avant-garde theatre, who became a primary influence in the development of the young man’s aesthetics. “Eisenstein’s belief in controlling the spectator through the performer’s bodily virtuosity; his emphasis on pantomime; his interest in Asian theater, the circus and the grotesque; even his 1930s attempt to create a curriculum in which film directors would undergo stringent physical and cultural training – all were initiated by the association with Meyerhold.”51 The central tenet that Eisenstein drew from his mentor was grounded in an acting style Meyerhold pioneered, biomechanics, that replaced studied gesture and overwrought language with an emphasis on automatic reflexive motions that arise naturally in the actor. Under Meyerhold, Eisenstein came to believe that the stage director’s goal is to be a “psycho engineer.” Using biomechanics, the director strings together freestanding moments of peak action that reflexively deliver the desired shock to the audience’s nervous system. By jolting the audience, the play will begin to turn their thinking toward the revolution. This belief in the power of art to motivate through reflex action drew not only on work of Meyerhold, but also on the contemporary experiments of Ivan Pavlov, the influential Russian psychologist who was demonstrating the power of classical conditioning by, among other things, training dogs in his lab to salivate to the ringing of a bell.

Beginning with the play Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man that he co-produced with Sergei Tretyakov in 1923, Eisenstein sought to bring the spectator to revolutionary action. Eisenstein, rejecting the “dramatic illusion” of traditional theatre, transformed the original play into a revue, with remarkable, circus-like moments of acrobatics, tight rope walking, and feats of agility. He even created a short film to include in the production. He described his new method in a short article, “Montage of Attractions.”

Theatre’s basic material derives from the audience: the molding of the audience in a desired direction. . . An attraction (in our diagnosis of theatre) is any aggressive aspect of the theatre, i.e. any element of it that subjects the audience to emotional or psychological influence. . . These shocks provide the only opportunity of perceiving the ideological aspect of what is being shown, the final ideological conclusion.52

For Eisenstein, the attraction is a way to dismantle the tradition of naturalism in theatre by focusing on the power of an independent moment of maximum performance, a “unit of impression,” in Tom Gunning’s words.53 The attraction prompts a direct response: an audience member sits in the physical presence of an actor, and the actor’s actions stimulate reactions in the primitive brain through a motor-imitative response in the audience. The motor-imitative response might arise as follows: the actor raises his fist on stage to strike another actor, and the audience experiences a primitive, reflexive mental response, an “inner recoiling” from that action.

For Eisenstein, biomechanical acting and the motor-imitative response it triggers in the audience opens up a new range of possibilities for stage and screen:

Thanks to such a construction of stage movement, there is no more need for an actor’s emotional experiencing of type, image, character, feeling, situation, since, as a result of expressive movement by the actor, the emotion experiencing is transferred where it belongs, specifically to the auditorium. . . It is precisely expressive movement, built on an organically correct foundation, that is solely capable of invoking this emotion in the spectator, who in turn reflexively repeats in weakened form the entire system of actors movements; as a result of the produced movements, the spectator’s incipient muscular tensions are released in the desired emotion.54

Later, applied to film, this acting style will often reveal a flaw: the “realistic, ritualistically repeated and abstracted behavior on the part of the actors and participants who tend to become walking concepts . . . typage figures.”55

Although there are two distinct periods in which Eisenstein theorizes about film’s potential – his writings from the 1920s during the early silent period, and his revision of those ideas in the 1930s and 1940s – his notion of the “attraction” is carried into his filmmaking and into his theorizing with few modifications. In 1924, barely a year after his original statement on theatre, Eisenstein pens an article “The Montage of Film Attractions.” Though he never defined the term concisely, in broad terms, the attraction for Eisenstein centered on both a visually expressive moment and the immediate shock effect on the viewer of seeing violent or frightful or surprising action represented (in film or theatre). Jacques Aumont points out that the ingredients that remain central to both are the attraction’s autonomy, and its visual impact, and its rejection of the need to express theme through traditional character action within a scene:

The attraction in cinema as well as elsewhere, thus supposes, first, a strong degree of autonomy (which will be expressed, in terms of montage, by the requirement of the high degree of heterogeneity) and, second, a visually striking existence (a requirement of effectiveness, as we shall see, but also a desire to be ‘anti-literary’ that was characteristic of the entire period) . . . Thus in cinema, the concept of attraction. . . will be what is opposed to any static ‘reflection’ of events.56

If the purpose of revolutionary art is to mold the spectator to the desired (political) end, then any striking aspect of theatre or film can serve as the attraction, as the “fist,” that will deliver violent shocks to the audience and conquer their inflexible beliefs. The word choice here – “fist” – is calculated. Dziga Vertov’s belief in the “Kino-eye,” the power of the “film machine” to reveal the world in a way unique to that device, is transformed by Eisenstein who famously wrote, “I don’t believe in the kinoeye, I believe in kino-fist.”57 And while Eisenstein’s use of the attraction is political, notice that it is not excluded from entertainment cinema, where it has a long history. The attraction, common in early silent film spectacle, lives on, though tamed by narrative in entertainment cinema: “The Hollywood advertising policy of enumerating the features of a film, each emblazoned with the command ‘See!’ shows this primal power of the attraction running beneath the armature of narrative regulation. . Clearly in some sense recent spectacle cinema has re-affirmed its roots in stimulus and carnival rides, in what might be called the Spielberg-Lucas-Coppola cinema of effects.”58

Beyond the central role of the “attraction,” “conflict” is the other key concept for Eisenstein in the 1920s, based on the prevailing philosophy of “dialectical materialism,” developed in the writing of Marx and Engels. Dialectical materialism is “the Marxian interpretation of reality that views matter as the sole subject of change and all change as the product of a constant conflict between opposites arising from the internal contradictions inherent in all events, ideas, and movements.”59 Adopted as the official Soviet philosophy under Stalin, historical events are seen as resulting from the conflict of opposing ideologies, a series of contradictions that give rise to new social orders. Eisenstein, writing in 1929, argues that conflict permeates film art, starting with the lowest physiological basis for the perception of movement in the viewer, because persistence of vision is conflict:

In the realm of art this dialectical principle of the dynamic is embodied in

Conflict

as the essential basic principle of the existence of every work of art and every form. . . in my view montage is not an idea composed of successive shots stuck together but an idea that DERIVES from the collision between two shots that are independent of one another. . . We know that the phenomenon of movement in film resides in the fact that still pictures of a moved body blend into movement when they’re shown in quick succession one after the other.60

In short, conflict drives the low-order, primitive brain function that allows the viewer to see movement in the projected image because persistence of vision collides sequential project frames on top of each other. Eisenstein goes on to distinguish his concept of montage from Pudovkin’s using the same model, a way to distinguish his broad approach to storytelling from the traditional approach of Pudovkin. Pudovkin’s sequential elements arrayed next to one another become Pudovkin’s shots as links in a chain. Eisenstein’s sequential elements arrayed on top of one another become Eisenstein’s shots as bundles of attractions in conflict.

Conflict, then, becomes the overriding principle in Eisenstein’s theory and later in “Film Attractions,” he argues that Pudovkin’s films use the “epic” principle of narration through a series of the hero’s great achievements arrayed next to each other, versus Eisenstein’s films that use the “dramatic” principle of narration through a collision of vivid contrasts. At this higher level of conflict, executive-level brain functions allow the viewer to synthesize new ideas from conflicting opposites. Thus, conflict is indispensable to a range of mental activities used to process film art: it is essential to both “bottom up” (sensation of movement) processes and “top down” (cognition) processes, essential to the viewer at both ends of the mental spectrum.

Given this plausible theoretical model, a central question for Eisenstein the filmmaker is more practical: “How can a conflict in the film form be used for a higher purpose, as the ‘Kino-fist’ to lead the viewer to the Marxist world view?” His first answer is “A Tentative Film Syntax,” one of two taxonomies he constructed in 1929. “Tentative” is the operant word – this is mental doodling, a piece of writing that reads like it was jotted down on a napkin, that might be just as accurately titled “Some Early Thoughts About How Montage Works on the Viewer.” Nevertheless, “Syntax” is consistent with his early theorizing: it is hierarchical and it reflects the Pavlovian milieu of his silent film work. Stripped to its basic form, the hierarchy of possible shot arrangements follows a hypothesized hierarchy of mental functions in the viewer, namely perception, emotion, and cognition. Drawing from Eisenstein’s “syntax,” we can try to summarize his thinking about the impact of conflict/montage on a viewer’s mental processes. (For clarity, Eisenstein’s writing is in italics.)

A Tentative Film Syntax61

I. Each moving piece of montage in its own right. With this cryptic line, Eisenstein reiterates that, at the lowest level, the counterpoint between two frames of film, the finest grained conflict possible – frame against frame – is what creates movement in cinema.

II. Artificially produced representation of movement. Eisenstein says that the following examples show primitive-psychological cases – using only the optical superimposition of movement.

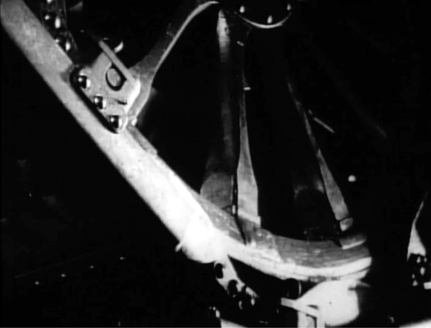

A. Logical. . . Montage: repetition of a machine-gun firing by cross-cutting the relevant details of the firing. At the level of the shot, we can mimic the creation of movement by inter-cutting short shots of relevant details. In October: Ten Days that Shook the World, Eisenstein intercuts shots of a machine gun (Figure 5.10) and shots of a machine gunner (Figure 5.11) in two frame shots that collide on a number of parameters including exposure or grey scale value and graphic mass.

The effect is a logical sensation of machine gun-like motion, recognized (or should we say felt) at the level of primitive-psychological perception. See Critical Commons, “October: Artificial Representation of Movement, Logical – Machine Gun.”62

B. Alogical. . . This device used for symbolic pictorial expression [in] Potemkin. The marble lion leaps up surrounded by the thunder of Potemkin’s guns firing in protest against the bloodbath Odessa steps. The effect was achieved because the length of the middle piece was correctly calculated. Super imposition on the first piece [Figure 5.12] produced the first jump. Time for the second position [Figure 5.13] to sink in. Superposition of the third position [Figure 5.14] on the second – the second jump. Finally the lion is standing. Struck by the effect of these three simple shots, Eisenstein wants to highlight both its psychological and intellectual forces. The lion rising is an overt, artificial representation of movement that works on a number of levels in the brain. From still shots of sculpture, it stimulates primitive brain functions to create motion. It also triggers psychological effects that Bordwell sees as multifaceted. “As literal filmic ‘animation,’ it snaps the spectator to attention. More specifically, the shots have an auditory effect. In whipping a snoozing lion into a roar, the editing synesthetically evokes the tumult of the barrage [seen in the previous shots].” 63 And clearly the lion sequence is also a metaphor: the revolution is waking even the sleeping stones. Or as Eisenstein puts it, “The jumping lions entered one’s perception as a turn of speech — ‘The stones roared.’”64

See Critical Commons, “Battleship Potemkin: Artificial Representation of Movement, Alogical.”65

III. The case of emotional combinations not merely of the visible elements of the pieces but principally of the chains of psychological association. Associational montage. . . As a means of sharpening (heightening) a situation emotionally. . . EMOTIONAL DYNAMISATION. The shooting down of the workers is cut in such a way that the massacre is intercut with the slaughter of a cow. (Difference in material. But the slaughter is employed as an appropriate association.) This produces a powerful emotional intensification of the scene.

Figure 5.10 From The Dramaturgy of Film Form (aka The Dialectical Approach to Film Form) (1929): Artificially produced representation of movement, logical. Just as the conflict between two frames of film – frame against frame – creates movement in cinema, Eisenstein argues that the conflict of short shots in montage can create artificial movement that arises logically. In October: Ten Days that Shook the World, Eisenstein intercuts shots of a machine gun . . .

Figure 5.11. . .with shots of a machine gunner in two frame shots that collide on a number of parameters including exposure or grey scale value and graphic mass.

Source: Copyright 1925 Goskino.

Figure 5.12 Artificially produced representation of movement, alogical: lion 1. Eisenstein claims the famous lion montage at the end of the Odessa steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin is a case of an artificially produced representation of movement, that is alogical. The first shot . . .

Figure 5.13. . .is super imposed upon by the second shot in conflict. Eisenstein claims a key to the impact here is that the length of the middle piece was correctly calculated, giving it time to sink in. . .

Figure 5.14. . .before the third shot of the lion leaping up is super imposed upon the second. Here the editing synesthetically evokes the tumult of the ship’s barrage . . . ”The stones roared.”

Source: Copyright 1925 Goskino.

Though it works through “primitive-psychological perception” – all perception of motion does – associative montage also functions at a higher level of mental activity to sharpen what the viewer feels. Attractions juxtaposed through montage create “chains of psychological associations” that startle and rouse the spectator to strong emotions, a further step in seizing the political consciousness of the viewer. See Critical Commons, “Visual Metaphor in Strike”.46

IV. The emancipation of closed action from its conditioning by time and space. The first attempts at this form made in the Ten Days film.

Example 1. (Ten Days)

A trench packed with soldiers [Figure 5.15] seems to be crushed by the weight of an enormous cannonball [sic: mechanized gun] descending on the whole thing [Figure 5.16]. Thesis brought to expression. In material terms, the effect is achieved through the apparently chance intercutting between an independently existing trench and a metal object with a similarly military character. In reality they have absolutely no spatial relationship with one another.

Reflecting on ways his silent films have worked to “seize the spectator,” Eisenstein notes that the traditional, rigid adherence to “closed action” – the diegesis contained by time and space, the traditional story space created through analytical editing – is limiting. Here, with the spatial relationship between the two shots unspecified, the thesis of the juxtaposition is made explicit, using images that function more like language: the capitalist war machine oppresses the working class. Eisenstein argues further that unlike theatre, where a murder scene would be shown in continuous time and space (in the stage space before the audience) and affect the audience like an item of information, a single shot in film is not the reality of the theatre space, but a concrete image that has the potential to evoke associations. Given this power, cinema should become discursive, moving beyond the methods of theatre towards the methods of language, which can give rise to new ideas by factual description.66

Here, using non-diegetic material entering apparently by chance – the “cannonball” (a mechanized gun) that has not been located in the diegesis – Eisenstein can make a thesis statement, a tertium quid, using visually concrete images to express new ideas, just like language. The false eye-line match created by the soldier looking up (Figure 5.15) contributes to the third meaning by explicitly thwarting the viewer’s expectation that the two are spatially connected. In the context of the film, where we have just seen early successes of the February Revolution and war weary Russian and German infantry exchanging food in friendly conversation, the mechanized gun descending (Figure 5.16) literally represents the “war machine” that continues to repress and crush the masses. The “war machine” in this instance is the provisional government, which the film has just shown honoring its commitment to the Allies rather than sue for peace. See “October: Ten Days that Shook the World, Cannon Lowers.”67

“A Tentative Film Syntax” is based on a broad underlying model of montage that rests on a hierarchical view of the viewer’s mind, a mind to be moved by embedded attractions from perception to emotion to cognition. Or as Eisenstein wrote, “From image to emotion, from emotion to thesis.”68 It builds on the notion that the very perception of motion in film dictates involuntary, “from the bottom up” processing (i.e., we can’t will ourselves to see a film as individual frames). And since biomechanics drives the motor-imitative response (i.e., we reflexively repeat an actor’s movement without conscious thought), “primitive-psychological perception” must be the foundation for the impact of montage. Eisenstein believes that when the director has transposed his theme into a set of attractions with a predetermined goal, the resulting pressures on the audience’s psyche will “arouse us” and “infect us” with emotion.69 At the highest level, the filmmaker can trigger cognition when he emancipates “closed action from its conditioning by time and space”; that is, when it uses quasi-diegetic or non-diegetic attractions within shots more like a language to communicate abstract ideas to the viewer.

Figure 5.15 “The emancipation of closed action from it’s conditioning by time and space”. Eisenstein argues that a montage using the non-diegetic insert (inserting a shot that is spatially unrelated) can release the associations of the concrete film images to create meaning more like the way language works. Here shots of soldiers in a trench who come under artillery fire . . .

Figure 5.16. . .are intercut with shots of a mechanized gun descending which literally represents the “war machine” that continues to repress and crush the masses.

Source: Copyright 1927 Sovkino.

But what precisely happens to the spectator confronted with these overtly discontinuous shots? Why and how do quasi-diegetic and non-diegetic shots create more abstract meanings? In the second typol ogy of montage that Eisenstein creates in 1929, “Methods of Montage,” he offers “a richer taxonomy of formal options. Instead of postulating a conflict between equal forces within the shot, Eisenstein proposes that every cut juxtaposes two shots on the basis of some salient feature, the dominant.”70 For Eisenstein, this is a carefully chosen word. “The dominant” obviously relates to music – the dominant chord in a diatonic scale – but as Bordwell points out, the idea also reflects Eisenstein’s continuing interest in physiology, to areas of the brain that “‘dominate’ a given behavior. More proximately, the term had also emerged in Russian formalist literary theory. . . the dominant as ‘the preeminence of one group of elements and the resulting deformation of other elements.’”71 The dominant is a factor in a sequence that is capable of working from the bottom up, and when it emerges, other attractions within the shot recede (and, as we shall see below, become “overtones”). Eisenstein writes,

Orthodox montage is montage on the dominant. I.e., the combination of shots according to their dominating indications. Montage according to tempo. Montage according to the chief tendency within the frame. Montage according to the length (continuance) of the shots, and so on.72

Eisenstein argues that a canonical montage would be cut “according to the foreground” or the “dominating indications.” That is, look at what two shots placed side by side are indicating to you as their most potent visual potentials – graphic, planar, volumetric, spatial, tempo or light values – in order to release emotion and meaning in the viewer. A reasonable suggestion, but should those “foreground properties” be edited in a way that places them in conflict or in harmony or somewhere in between? Should the cut juxtapose graphic contrasts that are large or minor? Should the sequence move from shots of slow tempo action into shots that are slightly more rapid or suddenly swift? Not surprisingly given that the range of potential “foreground properties” is very large, Eisenstein points out it could be any of these: “This circumstance embraces all intensity levels of montage juxtaposition-all impulses: From a complete opposition of the dominants, i.e., a sharply contrasting construction, to a scarcely noticeable ‘modulation’ from shot to shot.”73 Moreover, as the dominant emerges from a sequence, it may fluctuate from shot to shot – a series of shots might relate to one another in terms of their bright ness or value, but later shots in the sequence might relate to one another in terms of tempo – it is not “invariably stable.” And he goes on to give this concrete example:

If we have even a sequence of montage pieces:

A gray old man,

A gray old woman,

A white horse,

A snow-covered roof,

we are still far from certain whether this sequence is working towards a dominating indication of “old age” or of “whiteness.”

Such a sequence of shots might proceed for some time before we finally discover that guiding-shot which immediately “christens” the whole sequence in one “direction” or another. That is why it is advisable to place this identifying shot as near as possible to the beginning of the sequence (in an “orthodox” construction). Sometimes it even becomes necessary to do this with a sub-title.74

Clearly, Eisenstein is seeing an edited sequence as a dynamic system, and the notion of a “guiding shot” placed at the beginning of the sequence that “christens” a sequence is a powerful one: in the irreversible flow of moving images, earlier images obviously shape the perception of later ones, but here Eisenstein, always the mystic, is arguing for a shot that “baptizes the sequence to its community” or “christens the ship,” both naming it and dedicating it to its purpose. If the christening shot can’t be found, a title card (or later in the sound era, a line of dialogue, a sound effect or a musical element) may be necessary to identify the dominant.

Given that every shot is a plethora of potential attractions, when the dominant drives the editing of a sequence, the others must recede and become secondary. Rather than disregard these secondary properties, Eisenstein wants to account for their impact, however modest, by introducing the notion of overtone. In sound, every musical instrument’s middle A is 440hz, but the difference between the sound of a violin or cello comes from its timbre, or tone color, which is determined by the number and relative loudness of it overtones (harmonics). Rather than write off the potential for secondary stimulants in a frame to create meaning, Eisenstein maintains that even these secondary “overtones” can play a vibrant part in the impact of a sequence.

Equipped with these two notions, Eisenstein offers a second typology, “Methods of Montage,” to articulate the possibilities of montage. This time, the typology will not address effects on the viewer, but rather, montage techniques available in the film itself that follow the hierarchical Perception-Emotion-Cognition model. (Eisenstein’s writings in italics):

Methods of Montage75

1. Metric Montage

The fundamental criterion for this construction is the absolute lengths of the pieces. The pieces are joined together according to their lengths, in a formula-scheme corresponding to a measure of music. Realization is in the repetition of these “measures.”