4 David Bordwell, the Narrative Functions of Continuity Editing and Intensified Continuity

In Chapters 1–3, we looked at several schema for analyzing how editing works: Herbert Zettl’s notion of how screen vectors construct screen space, inductive versus deductive sequencing of images, Burch’s matrix describing 15 ways that a shot change can represent space and time changes, and the useful rules that Dmytryk and Murch offer about how eye movements and blinks can smooth the cutting across a shot. These are all basically “micro” conceptual approaches to understanding editing. They offer frameworks for understanding cutting at the level of the shot change.

David Bordwell takes a broader, “macro” approach that is useful for editors because it allows us to zoom in and out, from “micro” to the “macro” approach when looking at a longer narrative. It asks us to take a wider view of the story being assembled, giving special attention to how the editor controls the presentation of narrative events across the entire film as it unfolds, and how that unfolding presentation shapes the viewer’s construction of the film’s narrative. The “unfolding” of a film that an editor creates for the spectator is key:

In watching a film, the spectator submits to a programmed temporal form. Under normal viewing circumstances, the film absolutely controls the order, frequency, and duration of the presentation of events. You cannot skip a dull spot or linger over a rich one, jump back to an earlier passage or start at the end of the film and work your way forward. Because of this a narrative film works quite directly on the limits of the spectator’s perceptual cognitive abilities.1

Analyzing how a film’s cues us to construct a story is the objective of Bordwell’s book Narration in the fiction film, an early, influential work that gave a cognitive explanation of how films make meaning. His account of how films tell stories leads Bordwell to examine two broad aspects of the process, “Narration and Time” (chapter 6) and “Narration and Space” (chapter 7). As we have seen, Noël Burch views editing as the articulation of temporal and spatial relationships, and he looks to the cut to schematize those relationships. Bordwell takes this idea further by asking how these temporal/spatial cues are central to the viewer’s construction of a story. Armed with a broad schematic notion of how narration works, Bordwell proceeds to classify modes of narration that have emerged historically, and to give a credible account of how they tell stories including Classical Narration: The Hollywood Example (chapter 9), Art–Cinema Narration (chapter 10), Historical-Materialist narration: The Soviet Example (chapter 11), Parametric Narration (chapter 12), Goddard and Narration (chapter 13). But for our purposes, Bordwell’s account of narration’s relation to time and space is the most relevant to understanding editing in broad terms.

Bordwell looks at how the film parcels out pieces of narrative information – narrative “events” – by giving them an order, a duration and a frequency. Fundamentally, this is what editors do with the time/space fragments (i.e., shots) gathered at the shooting stage: the editor decides the order of the presentation of shots, the editor decides the duration or length of shots, and the editor decides whether or not parts of the narrative need to be repeated, and if so, how many times. With this formulation, Bordwell has distilled the essence of what editors do every day: they decide the order, frequency and duration of the audiovisual material they have. And though Bordwell’s focus is on how the editor parcels out narrative events within a narrative feature, the same principles apply to documentary editing or editing a:30 spot for a car maker. Editors decide what to show the audience first, second, third, etc. They decide the duration of each of those items. They decide which, if any, of the parts of the presentation bear repeating. And just to clarify, we are not excluding here the audio channels of a film: it is understood that our editorial decisions include what order we present sound elements to the audience, how long these elements are, and whether or not they are repeated. First, let’s lay some groundwork for understanding Bordwell’s theories, and then return to questions of order, frequency and duration in a moment.

Neoformalism Versus Interpretation: Building on Russian Formalism

David Bordwell is an American film theorist and historian who has authored a number of significant books in film studies. In 1985, he authored Narration in the fiction film and co-authored The classical Hollywood cinema: film style and mode of production to 1960, written in collaboration with Janet Staiger and his wife, Kristin Thompson. The latter book was very influential in film studies because of its innovative methodology: rather than write exclusively about films from the Hollywood canon, the authors selected 100 Hollywood films using an unbiased sampling procedure that ensured the author’s personal preferences were excluded from the process. Each film was then viewed shot-by-shot and logged for shot changes, shot durations, setting, lighting, camera movement, etc., producing a unique data set for the description of style, economics and technology of the classical Hollywood cinema. A professor at University of Wisconsin-Madison, Bordwell has gone on to write more than 15 books, including the introductory textbooks Film art (1979) and Film history (1994). His work has been influential and widely cited in contemporary film studies.

To explain how narration – the process of storytelling – works in fiction films, Bordwell takes a neoformalist approach, with a particular focus on the mental activities of the viewer who is “reading” the film unfolding before her. Neoformalism builds on the work of Russian formalists, an influential school of literary critics who used a “scientific” approach to identify the set of distinct properties that are specific to poetic construction and the properties of literature that are distinct from other forms of human activity. Bringing this approach to the analysis of film moves the consideration of editing from a single shot change into a larger arena, one that analyzes how films use the unique devices of the medium to tell stories. Bordwell believes this focus on how the audience mentally assembles a film narrative as the film unfolds is more useful than approaches that focus on interpreting a film. Interpreting a film means uncovering meanings that are implicit (i.e., “theme”) or symptomatic (i.e., “repressed” or “involuntary”). Often these methods of interpretation use a film or films to substantiate a larger, existing theory – a Grand Theory – such as Lacanian psychoanalysis. Bordwell outlines this kind of interpretative process in broad strokes as follows:

For example, the psychoanalytic critic posits a semantic field (e.g., male/female, or self/ other, or sadism/masochism) with associated concepts (e.g., the deployment of power around sexual difference); concentrates on textual cues that can bear the weight of the semantic differentiae (e.g., narrative roles, the act of looking); traces a drama of semantic transformation (e.g., through condensation and displacement the subject finds identity in the Symbolic); and deploys a rhetoric that seeks to gain the reader’s assent to the interpretation’s conclusions (e.g., a rhetoric of demystification).2

In contrast, neoformalism examines how the filmic text is constructed to trigger cognitive processes in the viewer to assemble a story. Bordwell argues that this sort of “mid-level theorizing” – i.e., close readings of specific film texts to understand how they cue the audience to construct a story without referencing a larger field like psychoanalysis – is a more useful approach than interpretation. This approach is grounded in Bordwell’s overarching notion of poetics, any

inquiry into the fundamental principles by which a work in any representational medium is constructed. . . [that] studies the finished work as the result of a process of construction – a process which includes a craft component (e.g., rules of thumb), the more general principles according to which the work is composed, and its functions, effects, and uses.”3

Story Construction

It is also grounded in Bordwell’s understanding of how the viewer behaves watching a film. Bordwell believes that a film viewer is active, reading cues in the film text and using prior knowledge, understanding of film conventions, the structure of the canonic story (e.g., to construct a coherent narrative using cause-and-effect). He devotes an entire chapter in his book Narration in the fiction film to describing how the viewer interacts with the film text unfolding on the screen. He summarizes his ideas in a short paragraph near the end of that chapter that is one of the clearest accounts of the mental activity of a movie viewer written.

To sum up: In our culture, the perceiver of a narrative film comes armed and active to the task. She or he takes as a central goal the carving out of an intelligible story. To do this, the perceiver applies narrative schemata [e.g., existing models of narrative that they bring to the viewing] which define narrative events and unify them by principles of causality, time, and space. Prototypical story components [e.g., in Bonnie and Clyde, “lovers,” “bank robbery,” “small southern town”] and the structural schema of the “canonical story” [e.g., introduction, complication, rising action, climax, denouement, coda] assist in this effort to organize the material presented. In the course of constructing the story the perceiver uses schemata and incoming cues to make assumptions, draw inferences about the current story events, and frame and test hypotheses about prior and upcoming events [e.g., did character X kill character Y, will character A marry character B?]4

Bordwell defines narrative as “a chain of events in cause-effect relationship occurring in time and space,”5 and a key question becomes “How does a film cue us to select relevant story information – ‘narrative events’ – and connect those events by cause and effect?” Notice that some, but not all, of the events in a narrative are explicitly presented in a film (or a novel, etc.). What we routinely call plot is the explicitly presented events that unfold in a film.

Films normally cue the viewer to make narrative inferences as they construct the story. These are not the moment-to-moment, non-conscious “from the bottom up” judgments that take sensory stimuli from a film and make inferences to create precepts: that is a car, it is night time, that is a burglar, etc. Rather, narrative inferences are conscious, “from the top down” judgments involving cognitive operations utilizing background knowledge, expectations, etc. Certainly, to create the narrative, the viewer makes inferences about the explicitly presented events (the plot). But also, when information is omitted, the viewer makes inferences about events not shown: a man and woman kiss goodnight by the woman’s apartment door, cut to the man and woman the next morning lying in bed, and we infer they have slept together. Films encourage “us to indulge in inferential elaboration,” writes Bordwell. “What is the product of that process? Basically, what we call the story.”6 Story then can be used to describe the larger unit that a film cues us to construct: it includes all the explicitly presented events (i.e., the plot) plus all the events we infer from the plot. Notice that in everyday usage, plot and story are often used interchangeably, but here we will use them distinctly: plot is what is shown, and story is all that plus the events not shown but inferred.

Bordwell finds it useful to label these different notions using the terms from Russian formalist narratology: roughly plot is syuzhet, the arrangement of events in the narrative text and story is “fabula, the story’s state of affairs and events.”7 He adds two final elements to complete his definition of narration: nondiegetic information and film style. The opening of The Maltese Falcon (Huston, 1941) contains a long, scrolling title that follows the film’s opening credits. It reads in part:

In 1539 the Knight Templars of Malta paid tribute to Charles V of Spain, by sending him a Golden Falcon encrusted from beak to claw with rarest jewels – but pirates seized the galley carrying this priceless token and the fate of the Maltese Falcon remains a mystery to this day.

Is this plot or story? It is doing the work of the plot – explicitly telling us part of the story – but not by giving us that information from within the story space of the film (i.e., it is not showing us Sam Spade in his office in California, interacting with the other characters, etc.) In other words, it is narrative information that is non-diegetic, or “outside the story space.” It is part of the text of the film as it unfolds but not, strictly speaking, plot. See Critical Commons, “Maltese Falcon: Opening Scene.”8

Film style is defined as “a recognizable group of conventions used by filmmakers to add visual appeal, meaning, or depth to their work.”9 Film style encompasses every aspect of a film: the filmmaker’s attitude towards the film’s concept, mise-en-scène, cinematography, lighting, sound usage and editing. Consider these two possible film versions of the tale of Jack and the Beanstalk. One opens in a traditional long shot as Mother opens her cabinet to find it bare, with Jack sitting nearby at a table with an empty plate, looking forlorn. The film cuts in closer, showing analytically the hunger and despair on Jack’s face. This first version goes on to tell the story chronologically: Jack takes the cow to town, is hoodwinked in to selling it for a few beans, returns home where his mother gets angry at him, etc. Another version of Jack’s story opens in a series of hand held camera shots from an extremely high angle, looking down over Jack’s shoulder at his house as he climbs furiously down the bean stalk shouting “Mom, Mom. . . get the ax! The giant is after me!” This second version will flashback at some point to fill us in on how Jack got into this predicament. Do these two distinct film plots tell the same story? Certainly the audience is cued to construct the same story, even though each presents its narrative events in a different order, and despite their different cinematic styles. The second version not only re-orders the syuzhet’s presentation of narrative events by opening with a climatic moment, it also chooses a kinetic camera/editing style that aims to position Jack immediately as the story’s protagonist caught in a precarious life or death struggle, hounded by a giant who is not far behind him. “Narration has to include matters of film style,” says Bordwell. “As we watch, in real time, online so to speak, we take the event as the narration presents it. Visual and auditory techniques are rendering the event for us, already organizing and slanting it in a certain way.”10 Elements of a film’s style – how the film deploys composition, camera placement, camera movement, lens usage, lighting, sound design and particularly editing – is a very significant part of communicating and organizing its narrative cues. As Bordwell notes, outside of any filmic elements that can be ascribed to excess,11 style in the classic Hollywood narrative always serves the narrative, and Hollywood style has highly regular attributes. In the abstract, a cinematographer can choose from a wide range of lighting styles, and one is as likely to choose one as another. But when shooting comedy, high key lighting – overall bright lighting that minimizes shadows and shadow density – is a much more likely choice, since that style of lighting functions within the comedy genre as a highly codified marker that the film is intended to be humorous. High key lighting is part of Hollywood’s “invisible style,” but only when used in a comedic film: the same choice in a murder mystery would not be nearly as “invisible.”12

Editing is no different here, with highly codified methods of articulating space (e.g., matched over-the shoulder shots for dialogue) and marking temporality (e.g., a dissolve marks the passage of time.) Editing in the classic Hollywood film will speak openly to the audience about space and time, orienting them in space by regularly returning to long shots that show the location and the arrangement of the characters, and orienting them in time with markers like fades to indicate the beginning and ends of scenes, etc. Clearly, editing is a particularly important element of Hollywood style because, for one thing, it controls the order of the presentation of narrative events in the film, and understanding the order of narrative events is critical to understanding a story, since causes must precede effects.

Here’s an example that Bordwell gives to demonstrate why cause and effect are key to understanding a narrative. Compare the two cases in Table 4.1. Case A is not a narrative, but in Case B,

We can connect the events spatially: The man is in the office, then in his bed; the mirror is in the bathroom; the phone is somewhere else in his home. More important, we can understand that the three events are part of a series of causes and effects. The argument with the boss causes the sleeplessness and the broken mirror. A phone call from the boss resolves the conflict; the narrative ends. In this example, time is also important. The sleepless night occurs before the breaking of the mirror, which in turn occurs before the phone call; all of the action runs from one day to the following morning. The narrative develops from an initial situation of conflict between employee and boss, through a series of events caused by the conflict, to the resolution of the conflict.13

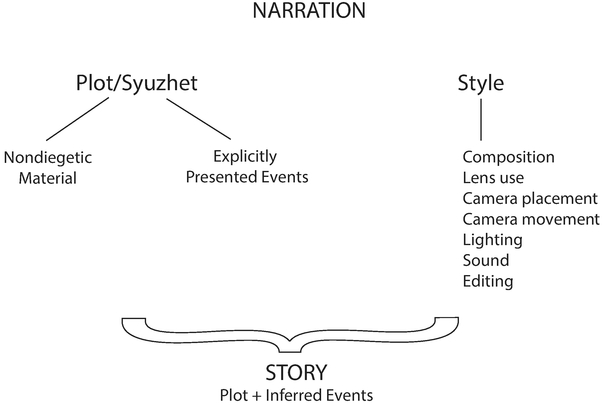

To sum up, Bordwell says: “I take narration to be the process by which the film prompts the viewer to construct the ongoing fabula on the basis of syuzhet organization and stylistic patterning. . . Narration is more than an armory of devices; it becomes our access, moment by moment, to the unfolding story. A narrative is like a building, which we can’t grasp all at once but must experience in time.”14 Or if we wanted to construct a visual model of how filmic narration looks it might look like Figure 4.1.

Editing and Canonic Hollywood Narration

After World War II, Hollywood films came to dominate world cinema, not only in number of films produced but also size of their audience. The unique voice of national cinemas in Europe, Latin America, Africa and Asia was difficult to maintain under the postwar, worldwide marketing

Table 4.1 How cause and effect are essential to the narrative

| CASE A | CASE B |

|---|---|

| A man tosses and turns, unable to sleep. | A man has a fight with his boss. That night he tosses and turns, unable to sleep. |

| A mirror breaks. | In the morning, he is so angry he smashes his bathroom mirror. |

| A telephone rings. | A telephone rings. His boss has called to apologize. |

Figure 4.1 The process of film narration. Bordwell proposes two systems that interact when a film tells us a story. First, there is plot – the unfolding narrative events presented by the film, the “programmed temporal form” that the spectator submits to – and second, the film’s style – the visual and aural techniques the filmmaker chooses – that shape and slant that form.

of Hollywood films, so much so that “at times Hollywood appears to be. . . no longer a national cinema but the cinema.”15 This dominance also extended to style: the cinematic devices and mode of narration that emerged in Hollywood became the dominant mode of cinematic storytelling around the world. Embodied in Hollywood studio filmmaking from roughly 1917 to 1960, this classic Hollywood style is marked by narrative logic and clear methods of delineating cinematic space and cinematic time, where all of the elements of style are used in service of the story.

Storytelling is a ubiquitous human activity: “Our conversations, our work, and our pastimes are steeped in stories. Go to the doctor and try to tell your symptoms without reciting a little tale about how they emerged.”16 Consequently, we are familiar with the classic devices and the standard structures of storytelling. “Once upon a time. . . ” cues us that what follows is likely a fairy tale. Classic narratives often follow a familiar pattern, beginning with an undisturbed stage, followed by a disturbance, an ensuing struggle, the elimination of the disturbance and a return to undisturbed stage. (Another way this overarching story structure is typically described is: introduction, complication, rising action, climax, denouement, coda.)

Hollywood films typically enact this narrative structure, Bordwell says, by presenting psychologically delineated characters struggling to solve well-defined problems or achieve specific ends. As the characters struggle in the narrative, they clash with others or with outer forces, and the film ends with a clear victory or defeat, a definitive answer to whether or not the characters have achieved their goals. So in the Hollywood film, it is the character, differentiated by evident traits, which becomes the primary causal force in the narrative. In similar fashion, one purpose the star system serves is to give an actor an approximate character prototype that can be adapted to a particular role. “The most ‘specified’ character is usually the protagonist, who becomes the principal causal agent, the target of any narrational restriction, and the chief object of audience identification.”17

And how does editing figure within classical narration? First, classic Hollywood editing fosters identification with the protagonist through the selection of shots that display his or her characteristic traits, that give him or her visual prominence in the film (i.e., more close ups, more screen time), and that positions the audience to see what the character sees (i.e., more shots explicitly or implicitly from his or her point of view.) Second, editing is the primary tool for structuring the narrative arc, in both “macro” terms (over the entire film) and in “micro” terms (within scenes). On the macro level, the plot will be broken into segments, whose boundaries are marked by a standard cinematic marker like a fade, a dissolve, overlapping audio or a return to the opening shot of the segment. Segmentation creates scenes of character action or a montage. Here, editing is critical to segmentation, visually specifying the beginning and end of a scene and marking out for the audience the “correct dosage” of story information that the filmmaker deems they can handle.

On the micro level, setting aside “Hollywood montage” sequences that condense and summarize causal developments before transitioning to a new scene, the classical Hollywood scene of character action follows phases much like the overarching narrative, beginning with an exposition, where establishing shots orient the audience to time of day, location and relative position of the characters. In the middle of the scene, closer analytical shots cover the dialogue coherently, showing characters working towards their goals and revealing character states of mind. Foregrounding the narrative through editing ranges from basic techniques – mixing the dialogue with music and sound effects for maximum audibility – to highly creative ones – revealing subtle aspects of a character’s facial expression and body language through careful selection and sequencing. For example, the choice, duration and sequencing of reaction shots is critical in dialogue editing, as it foregrounds states of mind that the dialogue may not address directly i.e., character A believes that character B is lying). And within a scene, the classically edited scene will control the release of new story information so that earlier story developments are closed off, and new lines open up, driving the narrative into the next scene. Classical editing is critical in this process as well, structuring a satisfying conclusion of a scene and simultaneously pointing where the action is headed in the next.18

Bordwell notes that while the “doubling” of characters or other narrative parallels may emerge, cueing the audience to uncover pertinent aspects of cause and effect in the story dominates in classical cinema. “Causality also motivates temporal principles of organization: the syuzhet represents the order, frequency and duration of fabula events in ways which bring out salient causal relations.”19 For an editor, this is a concise but revealing statement. Bordwell is focused here on a specific paradigm – “editing for causality” – in Hollywood cinema, but this statement reveals a broader axiomatic truth about all editing. If we set aside Hollywood’s emphasis on causality, the same notion applies fundamentally to all films, including documentary or experimental films: editing is the absolute control over the order of shots, the frequency of shots and the duration of shots.

When we examined Burch’s 15 possible spatial and temporal articulations, we looked at classically constructed temporal reversals or flashbacks, and temporal ellipses or flashforwards (see Chapter 2). Bordwell’s take on these phenomena looks not so much at how time and space change at the cut, but more broadly on the story constructing activities that time and space manipulations create: to reiterate, the syuzhet (the plot unfolding as the film progresses), absolutely controls the order, frequency and duration of fabula (story) events that the filmmaker wants to use to cue the spectator to construct a story. Consequently, we will first focus on temporal organization (order) and its relation to story construction, and examine some unique uses of temporal organization that Bordwell’s approach makes apparent. We will next examine how editing presents the frequency of narrative events in Hollywood cinema. Finally, we will look at how editing manipulates the duration of narrative events. Though classic Hollywood cinema dates from roughly 1917 to 1960, it will be more revealing in some instances to look at narrative films beyond these boundaries, films that are generally in the style of Hollywood films – they use continuity editing – but they also are pushing editing techniques in new directions that show how temporal and spatial organization in film can be expanded beyond the classical mode.

The Temporal Order of Narrative Events

As we noted above, the temporal order of narrative events is critical to understanding a story, largely because causes must precede effects. As we mentally construct the film’s fabula, we infer the story order from the order the syuzhet provides us. Bordwell notes that the syuzhet can present fabula events 1) simultanesouly or successively and 2) in linear order, or in a way that juggles their order through flashback or flashforward, yielding four possible relationships between the two:

| Fabula | Syuzhet |

|---|---|

| A simultaneous events | simultaneous presentation |

| B successive events | simultaneous presentation |

| C simultaneous events | successive presentation |

| D successive events | successive presentation.20 |

Case A: Simultaneous Events, Simultaneous Presentation

André Bazin, the French film theorist who is the subject of Chapter 6, argued that whenever the crux of a scene required the simultaneous presentation of two (or more) actions or elements, editing is ruled out.21 Using deep space composition or off screen sound or split screen, the filmmaker can present simultaneous events simultaneously to the viewer. Obviously, deep space composition is a directorial choice, not an editorial one. The use of off screen sound can be either a directorial choice at the shooting stage, or an editorial choice created in post. A split screen edit is primarily an editorial choice in postproduction, though scenes may be photographed with that goal in mind. Two good examples of the directorial approach to presenting simultaneous events simultaneously to the viewer are found in Hollywood films of the same year: Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941) and How Green Was My Valley (Ford, 1941). Both films exploit the spatial potentials of filmmaking to enhance story construction. While the deep focus cinematography of Gregg Toland on Citizen Kane is widely known today, the contemporaneous work of Arthur Miller on How Green Was My Valley, which won the Oscar that year, is not as widely recognized. Like Toland, Miller was interested in exploring deep focus cinematography:

I was never a soft-focus man. I like the focus very hard. I liked crisp, sharp, solid images. As deep as I could carry the focus, I’d carry it, well before “Citizen Kane.”22

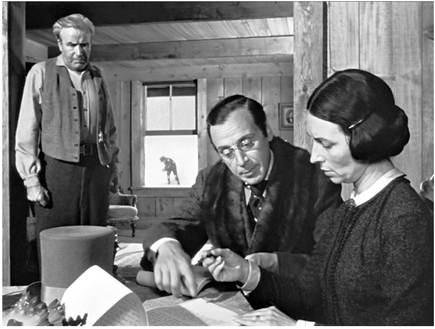

A crucial scene that launches Kane is the scene from Kane’s rural childhood told from Thatcher’s perspective. See Critical Commons, “Deep Focus Cinematography in Citizen Kane 2.”23 Kane plays in the snow outside the window, as Thatcher negotiates with his parents to take the young Kane to the city to raise him. Kane’s energetic play outside the window is in stark contrast to the somber transaction taking place inside, and the simultaneous presentation of both events elegantly comments on the unbound potential of youth and the promise of urban life, versus the economic and cultural boundaries of his aging parents (Figure 4.2).

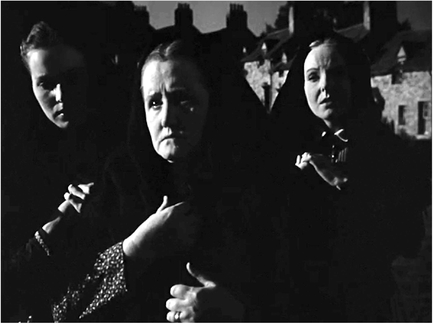

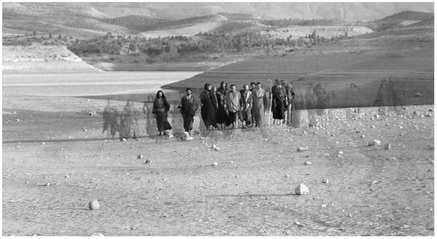

That same year, Miller used deep space and off screen sound in How Green Was My Valley for similar ends. The tension between family ties, tradition and a dying way of life versus the need for money and the economic promise of America is shown by the simultaneous presentation of two narrative events. In the film, a town of Welsh miners is split over a bitter strike called at the mine when the owner lowers wages. The Morgans, a family whose father and sons all work in the mine, mirror this split when the father sides with the owner. When the strike ends, the town and the family are reconciled, but it is clear that the industrial economy beyond their little valley will not support the mine for much longer. The town is destined to decline and two Morgan boys decide to seek a better future in America. A letter arrives asking that the miners’ choir – formed from the Welshmen who love to sing as they walk to and from work – perform before Queen Victoria at Windsor castle. See Critical Commons, “Deep Space and Off-screen Sound in How Green Was My Valley.”24 As the choir rehearses that night, the father leads the men in a prayer of thanks to God as their father and Queen as their mother. The choir sings “God Save the Queen,” the British national anthem, and the camera cuts to a shot of three women – the Morgan mother, her daughter and daughter-in-law – looking on with tears glistening in their eyes. The camera then tracks right to an empty street, the two Morgan boys enter frame, and the camera holds: they walk quickly up the darkened street, off to seek their fortune in America as the choir concludes the anthem with a resounding “God save our Queen” (Figures 4.3, 4.4).

Figure 4.2 Simultaneous presentation of narrative events in Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941). The deep focus style employed in Citizen Kane allows the simultaneous presentation of simultaneous narrative events: the energetic play of the young Kane outside the window contrasted with the somber transaction taking place inside, where Kane’s parents are signing the papers for him to be taken to the city by Mr. Thatcher.

Source: Copyright 1941 RKO Radio Pictures.

Here, the tracking camera seems at first unmotivated. But the move links the two spaces and their underlying connotations: Ford simultaneously presents the older society, the choir, Welsh women dressed as if in mourning, tied to religious tradition, the monarchy and a dying economy, and the tracking shot reveals the younger generation walking briskly off on a new quest for a new life in America.

These scenes from Kane and How Green Was My Valley are both examples of Case A, simultaneous events, simultaneous presentation. Such scenes might seem trivial material for analysis: aren’t there thousands of films that simultaneously show two narrative events within a single

Figure 4.3 Simultaneous presentation of narrative events in How Green Was My Valley (Ford, 1941). In How Green Was My Valley Ford uses a tracking camera to move from a view of the Morgan women . . .

Figure 4.4 to the Morgan boys who are leaving for America. According to French film theorist Jean Mitry, deep focus, movement in the frame and camera movement become points where the filmmaker’s arrangement of visual material can create a “montage effect,” with or without out cutting. Here the juxtaposition is between the old way of life of the miners and the promise of a new life abroad.

Source: Copyright 1941 20th Century Fox.

frame? Is every use of a sound bridge a candidate for close analysis under Bordwell’s scheme? Probably not, unless we are systematically cataloging a film’s temporal relations, methodically thinking through the moment-to-moment relationships of syuzhet presentation (and ultimately how these moments cue fabula construction). On the other hand, these two scenes stand out as vivid examples of simultaneity because of the juxtaposition of two opposing forces within the same frame. Jean Mitry, a French film editor turned film theorist, wrote about this phenomenon in his monumental book, Esthétique and Psycologie du cinéma (1963–1965). In an attempt to synthesize a middle ground between the earlier Soviet montage theorists like Eisenstein and the realist theorists like fellow Frenchman André Bazin, Mitry took a phenomenological approach to theorizing how film worked by asking what are the fundamental, unchanging elements of the subjective experience of watching a film? He argued that montage is not merely an effect that arises through editing. Rather, deep focus, movement in the frame and camera movement become points where the filmmaker’s arrangement of the profilmic material can create in the viewer a montage effect, with or without out cutting. In fact, Mitry argued that the montage effect was one of four defining, invariant underlying structures of all filmic phenomena, regardless of cinematic style, historical period, genre, etc.25 Here, deep focus and a camera move provide simultaneous presentation for a collision montage effect, using Mitry’s term, and otherwise they might go unnoticed.

Beyond the potential of the camera to create simultaneous presentations of narrative events, “split screen” – a term that describes the composting of two or more images into a single film frame – is a postproduction technique that is frequently used to do the same thing. We have seen this method emerge in motion pictures as early as 1907, in Edwin S. Porter’s College Chums (see Chapter 2, p. 54), a style chosen in that instance which references the earlier mode of production seen in lantern slides. Other early uses of split screen are found in more experimental work: Man with a Movie Camera (Vertov, 1929) and Ballet Mècanique (Léger and Murphy, 1924) are notable examples. Split screen editing in narrative films has been relatively rare, initially because of the relative difficulty of producing the effect in film in an optical printer, where the two images would have to be printed onto the same strip of film. As the technique has become technically easier in the domain of live television and the digital postproduction world, its use in television newscasts, television commercials and title sequences has become widespread. Michael Betancourt argues in Beyond spatial montage: windowing, or the cinematic displacement of time, motion and space, that split screen editing is actually part of a bigger phenomenon called windowing,

not exclusively or only a matter of editing but of the visual organization of materials within the frame. Since the 1980s there have been several competing terms used for this same morphology: collage, mosaic-screen, spatial montage, split screen, temporal image mosaic, and, less commonly, parallelism (video art) and windowing (digital art). All identify the presentation of multiple images (shots) simultaneously on screen, all juxtaposed in a fashion that has direct parallels in both graphic design and comics.26

The graphic nature of split screen production was featured in a 17 screen film created by Ray and Charles Eames for IBM at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York City, ushering in its use in a number of Hollywood films in the 1960s. After seeing the IBM exhibition, John Frankenheimer shot Grand Prix in 1966 using Super Panavision 70mm, over a five-month period on actual racing tracks in Europe, using 21 racing cars, a specially adapted camera car and a small helicopter with the newly developed Tyler camera mount. The film used multiscreen editing techniques in a number of sequences in the film. It also won three Oscars for technical achievements and was one of the ten highest grossing films of 1966, further popularizing multiscreen editing techniques, a trend that continued in films like The Thomas Crown Affair (Jewison, 1968), Woodstock (Wadleigh, 1970), Airport (Seaton, 1970) and The Andromeda Strain (Wise, 1971).

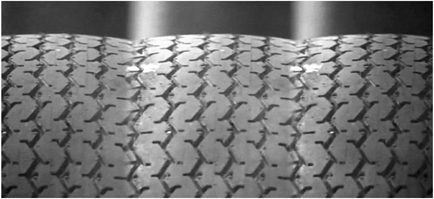

Grand Prix’s opening title sequence by Saul Bass includes a range of shots where a single shot is printed multiple times – not an instance of Case A, simultaneous events, simultaneously presented (there is only one event) – but rather, the creation of a graphic grid of a single moment in time that is repeated spatially across the screen. For example, in one shot, a spare racing tire is rolled towards the camera and stops. By vertically carving the screen into a triptych, Bass takes the vertical graphic element of the tire and spatially multiplies it into an imposing triptych of tire and tread (Figure 4.5).

Later in the same sequence, the graphic repetition of an identical shot of a mechanic tightening a spark plug wrench (Figure 4.6) is repeated, first printed in a 2 × 2 array – a four panel shot – then a 4 × 4 array – a 16 panel shot – and ultimately in an 8 × 8 array – a 64 panel shot (Figure 4.7) that suggests all the racing teams are performing the same mundane tasks as the start of the race approaches. See Critical Commons, “Opening title sequence for John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix.”

Betancourt calls this “single image displacement,”27 where the editor transforms

a singular image to create a pattern of identical elements typically composed in a grid. . [T]he spatial repeating of the single shot creates a continuous field of imagery that acts to emphasize the graphic character of the image rather than the uniqueness of visual contents. Juxtaposed imagery is secondary to the continuous pattern formed.28

The graphic character of these spatial multiplications – the four panel shot, 16 panel shot and 64 panel shot – is further emphasized because all the multi-panel shots move forward in time using a single, long duration take of the turning wrench. So there is a perfect temporal match as each panel shot multiplies, emphasizing the graphic pattern established.

Later in the film, a race in the Netherlands is punctuated with a four panel split screen that shows the four main characters – Jean-Pierre Sarti (Yves Montand), a French racer, Pete Aron (James Garner), an American driving for an upcoming Japanese company, Scott Stoddard (Brian Bedford), a British driver who is recovering from a crash, and Nino Barlini (Antonio Sabàto), an Italian racer – racing in medium shots. The simultaneous presentation of their intense concentration, as they wrestle with the cars’ steering over uneven ground, emphasizes the physical demands of the sport. Here, the four panel shot (Figure 4.8) is also a structuring device: the film returns to the four panel shot three separate times and then each quadrant is expanded to fill the screen, giving three drivers a short sequence that shows their struggle in the Dutch national race, as first Barlini spins out, then Stoddard nurses his sore knee in the cockpit, and Sarti breaks an accelerator cable. Using the four panels becomes a way to reiterate that the main characters are still in the race, simultaneously focused, and facing similar difficulties at every turn.29 See Critical Commons, “Montage of split screen driving sequences from John Frankenheimer’s Grand Prix”.

A more recent use of split screen opens Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream (2000). Sara Goldfarb’s son Harry is a drug addict and comes to steal his mother’s television set. See Critical Commons, “Split-screen in the Opening of Requiem for a Dream.”30 As Sara (Ellen Burstyn) hides in the closet, Harry (Jared Leto) becomes increasingly angry with her and Aranofsky uses a split screen to simultaneously present both the interior of the living room closet (and occasionally Sara’s subjective point of view of the living room through a hole in the closet door) and Harry’s rampage in the living room as he works to steal the television set she has chained to the radiator to keep him from stealing (Figure 4.9).

Part of Aronofsky’s strategy here is to replace traditional “objective” camera placements with ones that are more subjective, rendering the isolation and alienation of the main characters who suffer from addiction, particularly Sara’s descent into psychosis. By simultaneously presenting the mother’s fear – her dark, confined entrapment shown in close up and in claustrophobic subjective shots through a matte shot of the door’s “keyhole” – and the son’s rage – his maniacal pacing back

Figure 4.5 Tire triptych in Grand Prix. In Grand Prix, Saul Bass takes the vertical graphic element of the tire and multiplies it into a triptych.

Source: Copyright 1966 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Figure 4.6 Grand Prix: Single image displacement . . . A shot of mechanic tightening a spark plug wrench .

Source: Copyright 1966 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Figure 4.7 creates a pattern of identical elements composed in a grid.. . is repeated as a four panel shot, a sixteen panel shot, and ultimately this sixty-four panel shot.

Source: Copyright 1966 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Figure 4.8 Grand Prix: Four panel shot as a structuring device. Returning to the four panel shot becomes a marker of the beginning of sequences that show each driver’s individual struggle to win the race.

Source: Copyright 1966 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Figure 4.9 Splitscreen in Requiem for a Dream. By simultaneously presenting the mother’s fear and the son’s rage, director Daniel Aronofsky makes their estrangement and isolation visually explicit as addiction takes over both their lives in Requiem for a Dream.

Source: Copyright 2000 Artisan Entertainment.

and forth, berating his mother for hiding the key to the television – the split screen in Requiem makes concrete their estrangement and isolation. Addiction is taking over both their lives – only later will we learn of Sara’s developing addiction to weight loss pills. In addition, the split screen simultaneously presents both “cause” – the depth of Harry’s addiction as he steals the television (or more accurately, steals again, or why would she have chained it?) and “effect” – a mother’s fear of her own son, meekly enabling his addiction by turning over the key. On screen are two contrasting states of being that are starkly opposed to our traditional image of mother and child, with the divided screen graphically emphasizing the split between them. Later, when both are addicted we can see this split screen opening as both a split between them and a side by side comparison of their condition.

Like the camera track in How Green Was My Valley, it is this pointed aesthetic choice, the split screen that cues the audience to the implicit meaning of the scene, a meaning beyond what an ordinary edit of the scene might create. Betancourt recognizes this effect when he says that the combination must be seen by the audience as an assembly:

Juxtaposition depends on the recognition that the collection of imagery appearing on screen is not the autonomous action of a long take “recording” actions in front of the camera but rather a con sciously chosen – designed – product of human activity. Where the autonomous action of the cam era is treated as a “given,” producing imagery that is continuous, in contrast, juxtaposed imagery is already selected and assembled; juxtaposition is not understood as an autonomous product.31

Here, Aronovsky’s overt aesthetic choice of the split screen manifests his intent within the opening scene, launching the narrative that he says, “is not about heroin or about drugs. . . The Harry-Tyrone-Marion story is a very traditional heroin story. But putting it side by side with the Sara story, we suddenly say, ‘Oh, my God, what is a drug?’ ”32

Case B: Successive Events, Simultaneous Presentation

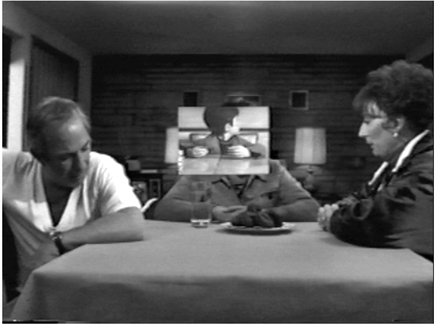

Presenting narrative events from different time frames simultaneously is rare in cinema, and usually requires motivation through a technical device such as replaying a recorded video event or character subjectivity such as an imagined memory. In David Lynch’s Lost Highway (Lynch, 1997) the motif of video replay comes early in the film, as a series of VHS video tapes are left on the door step of Fred Madison (Bill Pullman), a Los Angeles saxophonist who gigs at clubs and suspects that his wife Renée (Patricia Arquette) might be having an affair. See Critical Commons, “Lost Highway: Second Video Replay.”33 The first tape that arrives shows only a black and white long shot of the exterior of the house, and a cut in to a zoom shot of their door. Renée dismisses it as something that must have come from a real estate agent. The second tape, however, arrives the morning after Fred and Renée have had sex, and Fred has recounted a disturbing dream he had in which a figure he was in bed with turned out to be an old man, not Renée. They sit down to watch the tape, and it opens with the same long shot and cut in to their door. At first they think it is the same tape, but as it continues with a grainy fisheye view of the inside of their apartment, the camera moves through the living room, down the hall, and into their bedroom showing them sleeping at a previous time. The reaction shots of Fred and Renée observing the tape get closer, ending with extreme close ups of them cut against the final shot of the video tape playing on the television, framed so tightly that the screen is merely moving pixels, barely readable. The tape ends in static. The subjective shot of the camera walking into their bedroom, simultaneously presented with their reactions in extreme close up, positions them as intruders into the sanctity of their most private space, an eerie kind of “stalking by proxy” that would not be possible to present without the videotape’s ability to offset time.

Another instance of Case B: successive events, simultaneous presentation is found in the independent film Buffalo ’66 (Vincent Gallo, 1998). See Critical Commons, “Buffalo ’66: Successive Events, Simultaneous Presentation.”34 In the film, Billy Brown (Vincent Gallo), just released from prison for a crime he did not commit, kidnaps a girl and forces her to return to his mom and dad’s house posing as his wife. With the Buffalo Bills football game droning on in the background, they have an extended scene at the dining table that shows how dysfunctional the family is. At one point, Billy’s mother brings him chocolate donuts for a snack, and Billy does a slow burn while reminding his mom that he is allergic to chocolate and pointing out that his own mother is unaware of this. In some ways, the scene is a “recounted enactment” (discussed further below) where his telling of his childhood allergy leads to a flashback: we eventually see him as a child, eating chocolate donuts with a swollen face. But here, the unconventional methods used to render the simultaneous presentation of the successive events makes the reversal a “flaunted temporal reversal” that is extremely overt. The incoming shot of Billy as a child is rendered as a center wipe, entering the screen “from Billy’s head” (Figure 4.10), until it almost fills the screen, while the outgoing shot is held underneath until it fades out at the same point. The incoming shot of the young Billy eating chocolate is ultimately held as a freeze frame, while the adult Billy continues to berate his mother for not remembering her own son’s allergy. The entire scene, which never really leaves the “audio present” of the adult Billy berating his mom, takes:16 seconds, long enough that what we would ordinarily call a transition, here is more accurately called a pointed simultaneous presentation of successive narrative events. The difficulty of presenting successive events simultaneously in motion picture is suggested by this weirdly rendered scene, where the transition is in an important sense the scene, and the outgoing audio never really leaves the present. No wonder that this arrangement of narrative events is rare.

Figure 4.10 Buf falo ’66: successive events, simultaneous presentation. The difficulty of presenting successive events simultaneously is suggested by this weirdly rendered scene, where the transition is the scene.

Source: Copyright 1998 Lionsgate Films.

Case C: Simultaneous Events, Successive Presentation

Case C – commonly called crosscutting or parallel action – represents one of the first narrational strategies employed by early filmmakers, and is common. With two lines of action happening simultaneously, crosscutting offers the editor an easy way to show the course of both actions by spreading them out one after the other in the syuzhet: cut from Jones doing “x,” to Smith doing “y,” and continue this until the actions are concluded.35

We have looked before at classic crosscutting from The Godfather (see Chapter 2, p. 75), where the baptism of Michael’s nephew is cross cut with the executions of his Mafia rivals across town. There, we classified that arrangement of space and time under Noël Burch’s scheme, Case 11 Spatially Discontinuous Radical, Temporally Continuous. Rather than present narrative events in the same frame, simultaneity is presented as the editor moves back and forth between more or less distant locations, as time moves forward more or less linearly.

I say “more or less” because this common notion of crosscutting glosses over some of the spatial-temporal nuances that also arise when crosscutting. Crosscutting has been used from the early days of cinema for the “last minute rescue,” a cinematic figure of style attributed to D. W. Griffith. In this use, the victim under attack – e.g., the victim tied to the railroad track – is being rescued by a distant hero – e.g., the hero in the nearby town – who must hurry to the victim’s aid, so the initial cutting is, in fact, Spatially Discontinuous Radical, Temporally Continuous. But ultimately, as the hero arrives at the scene of the rescue, the spatial relationship moves inevitably closer: the shots necessarily become Spatially Discontinuous Proximate, Temporally Continuous as the hero approaches, and eventually, Spatially Continuous, Temporally Continuous as the hero physically saves the victim by untying them from the track. Similarly, time in the “last minute rescue” is “more or less” linear: it does move inexorably forward, but traditionally editors extended or shortened either side of the “threat” side of the equation or the “rescue” side of the cutting equation to maximize the tension of the scene.

Bordwell makes note of this phenomenon discussing crosscutting in Christopher Nolan’s Inception (2010):

One thing that has long struck me about classical crosscutting is that in one line of action time is accelerated, while in another it slows down. The villains are inches away from breaking into the cabin/ the hero is miles away/ the villains are almost inside/ the hero is just arriving. . I wonder if Nolan noticed this aspect of the crosscutting convention and built it into his plot, supplying motivation. . . by stipulating that different dream levels have different rates of change.36

Indeed, Inception is a science fiction thriller whose main character Dominick Cobb (Leonardo diCaprio) leads a team of “extractors” to create four levels of nested dreams to implant subconsciously in the mind of the son and heir of a giant energy conglomerate, Robert Fischer (Cillian Murphy), the idea being that the conglomerate should be dissolved. See Critical Commons, “Inception: Montage of Ariadne Awakening.”37 Here, Bordwell finds parallels with Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), an early “nested narrative,” that Inception mimics, providing a puzzle film structure that appeals to Nolan, a director of intricate, innovative narratives like Memento (2000). To help viewers stay oriented, Nolan visually differentiates each dream level – rainy L.A. streetscape, an understated hotel, a snowy mountain fortress and the mixed urban landscape of limbo – and gives each dream level its own clock speed, with time in the lower levels passing more slowly than “real time,” an idea announced early in the film by showing a second hand on Cobb’s watch accelerating before cutting from the dream level he’s currently inhabiting to the real world “above.” Nesting the stories within dream levels gives Nolan many opportunities for bravura cross cutting:

What Nolan has done is created four distinct subplots, each with its own goal, obstacles, and deadline. Moreover, all the deadlines have to synchronize; this is the device of the kick, which ejects a team member from a dream layer. With so many levels, we need a cascade of kicks. . .. The last forty-five minutes of the film become an extended exercise in crosscutting. As each plotline is added to the mix, Nolan can flash among them, building eventually to four alternating strands – with additional crosscutting within each strand (in the hotel, Cobb at the bar/ Saito and Eames in the elevator/ Arthur and Ariadne in the lobby). Each level has its own clock, with duration stretched the farther down you go.38

In the climax of the film, the van holding the team of extractors in dream level one drives off a bridge – the intended “kick” to be synchronized with “kicks” at other levels – that will wake the dreamers at every level. In every subsequent shot in dream level one, the van’s descent to the water is shown in extreme slow motion, and structurally, from the point it breaks through the bridge’s guardrail until it hits the water, roughly 27 minutes of screen time elapses. The van’s actions “above” are crosscut with actions in levels “below,” beginning with a cut from breaking through the guardrail to an avalanche triggered in the snowy mountain level (Figures 4.11 and 4.12)

Like Coppola’s baptism scene, where the anointing of the baby synchronizes with the killing of Michael’s rivals across town, this first cut from the van suggests the power of distant actions, a smaller scale impact at one level having a large scale impact at a lower level. And like the baptism scene, where the baptism in the church carries metaphorically into the other strands of action where a “baptism of blood” is inaugurating Michael into the Mafia, Nolan’s cross cut here emphasizes the mystical, ineffable connections across the dream world “strands” because this cut is also a cut on an idea – van cascading over the bridge cut to the snow cascading down the mountain.

The audacious crosscutting between dream levels culminates as the van slowly hits the water, and the dreamers are extracted from each level. Nolan uses a series of loosely matched shots of Ariadne (Ellen Page) distributed across a montage of the dream worlds imploding, showing her waking in each level (Figures 4.13, 4.14, 4.15, 4.16).

Figure 4.11 Cross cutting in Inception: outgoing shot. Actions in the dream levels “above” are crosscut with actions in levels “below,” like this cut from the van breaking through the guardrail to . . .

Figure 4.12 Cross cutting in Inception: incoming shot. . . .an avalanche triggered in the snowy mountain level.

Source: Copyright 2010 Warner Bros. Pictures.

Figure 4.13 Nested narrative montage: the “kick” cross cut across dream levels. A series of loosely matched shots of Ariadne (Ellen Page) mark the moments she awakens at the limbo level and . . .

Figure 4.14 at the snow level and . . .

Figure 4.15 at the hotel level and . . .

Figure 4.16 at the van level.

Source: Copyright 2010 Warner Bros. Pictures.

Bordwell concludes that the problem with these kinds of innovative narrative structures,

is how to fill in the plotlines. Let me suggest a general principle, at least for storytelling aimed at a broad audience: The more complex your macrostructure is, the simpler your microstructure should be.. . [Nolan] recruits the conventions of science fiction, heist movies, Bond intrigues, and team-mission plots like The Guns of Navarone to make the scene-by-scene progression of the plot comprehensible. The iterated chases and fights keep us grounded too.39

Crosscutting between levels becomes the “macro structuring” technique that knits the four dream levels together.

Another hybrid method of crosscutting commonly used by editors mixes cases of A and C – simultaneous and successive presentation of narrative events – into a single sequence. How is this done? Typically mixing Case A and Case C simply means overlapping sound (simultaneous presentation) from two locations that are crosscut (successive presentation). See Critical Commons, “Midnight Cowboy: Opening Sound Bridges.”40 The opening of Midnight Cowboy (Schlesinger, 1969) offers just such a case as Joe Buck (Jon Voight) dresses to leave his job as dishwasher in a small Texas town for New York City. Joe sings a traditional cowboy ballad “Git Along Little Doggies” in the shower and dresses before the mirror, when a line of off screen sound from a female voice intrudes: “Where’s that Joe Buck?” (Case A, j-cut. For an explanation of j-cuts and l-cuts, see Glossary.) The film then cross cuts to a diner where Joe is expected to show up for work: a fellow dishwasher in a waist shot, surrounded by stacks of dirty dishes, reiterates, “Where’s that Joe Buck?” (Case C). As the film cross cuts back to a close up of Joe removing a new cowboy hat from a box, the off screen sound from another male voice continues the pattern: “Where’s that Joe Buck?” (Case A, l-cut.) As he places the hat on his head, the female voice returns, “Where is that Joe Buck?” (Case A, j-cut), then cross cuts the woman in a medium close up, looking through the kitchen pass-through stacked with dirty dishes saying “Where is that Joe Buck? Look at this crap” (Case C). A quick cross cut back to Joe as he continues to dress seems to answer the question as he sneers rhetorically, “Yeah, where is that Joe Buck?” (Case C). The scene continues in this pattern, alternating off screen sound with cross cut shots. It concludes with the restaurant owner delivering an ultimatum straight into camera, “You are due here at 4 o’clock,” cut to Joe (Case C), also looking straight into the camera, who seems to reply directly to him, “You know what you can do with them dishes. And if you ain’t man enough to do it for yourself, I’d be happy to oblige” (Case C). Here, as the lines of dialogue delivered directly to camera are cut back and forth, the point is to create the false sensation that they are speaking to each other in person, i.e., the two shots are masquerading as “temporally continuous, spatially discontinuous proximate” to use Burch’s nomenclature.

Case D: Successive Events, Successive Presentation

If narrative events are in no way simultaneous – neither simultaneous in the fabula or syuzhet – Bordwell says they represent Case D: Successive events, Successive presentation. Notice that “successive” in this instance means “following another without interruption,” but not “following another without interruption in some predetermined order.” Bordwell spells this out clearly when he distinguishes the fabula, chronological by its very nature, from the syuzhet that can be chronological or not. While ordinarily presenting “fabula successivity” as “syuzhet successivity” (as opposed to simultaneity), the syuzhet routinely takes the liberty of reordering the presentation of events, notably through flashbacks.41 We have examined how Burch’s 3 × 5 matrix deals with these temporal manipulations at the micro level, that is, at the level of the cut. (See Chapter 2, p. 59). Flashforward, as we noted in Chapter 2, is relatively rare in classical cinema, as it is difficult to motivate realistically, because we expect the syuzhet to match the irreversible forward motion of time. Consequently, the “flashforward tends to be highly self conscious and ambiguously communicative. This is doubtless why classical narrative cinema has made no use of it and why the art cinema, with its emphasis on authorial intrusion, employs it so often.”42

Regarding the flashback, Bordwell makes a further distinction that Burch does not. Because Bordwell’s approach seeks to explain the macro process of filmic narration he wants us to recognize that a flashback can be either recounted or enacted: in other words, when a character communicates prior fabula events by speech or writing or video recording, etc., that is a recounting, but when prior fabula events are presented as if they were occurring in the moment, that is enactment.43 Such a distinction is needed, Bordwell argues, because films can show prior events or tell prior events, and it’s common for film characters to discuss prior fabula events in dialogue.44

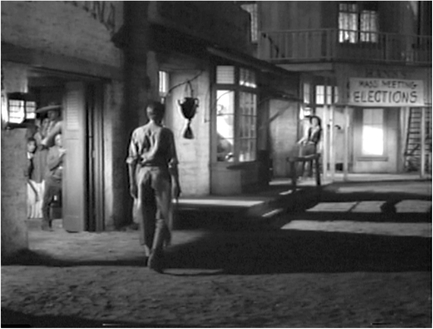

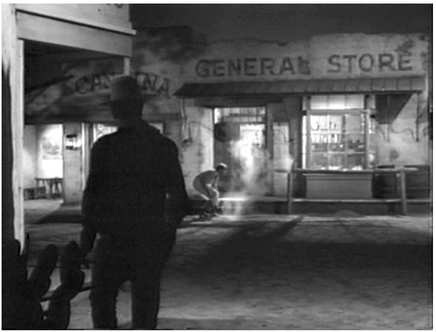

A particular hybrid form of the flashback in film that uses both methods is the recounted enactment, where a character begins telling an earlier narrative event, and the film cuts back to show that event.45 The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (Ford, 1962) contains a vivid example of the conventional Hollywood style of this form. Ransom “Ranse” Stoddard (James Stewart), a lawyer raised and educated in the East, comes to Shinbone in the Western territories, to set up a law office. He competes with the rancher Tom Doniphon (John Wayne) for the attention of Hallie (Vera Miles), and ultimately brings law and order to the town by shooting a local thug who terrorizes the town – Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin) – or so he thinks (Figure 4.17). See Critical Commons, “Flash Back: The Original Scene in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance that Later Replays as a Recounted Enactment.”46 The first version of the shooting scene becomes the basis for comparison to the enactment that comes in a flashback later as Doniphon recounts the event, and Ford cuts to show it from his point of view.

At the convention to establish statehood, Stoddard is under consideration as the territory’s delegate to Washington, but storms out after he decides he’s unfit, given that his current fame is based on the fact that he killed a well known bad guy. See Critical Commons, “Flash Back: Recounted Enactment in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.”47 Doniphon takes Stoddard aside and tells him, “You talk too much. Think too much. Besides, you didn’t kill Liberty Valance. . . Think back Pilgrim [Stoddard]. Valance came out of the saloon. You were walking toward him when he fired his first shot. Remember?” (Figure 4.18) The camera pushes in on these last two lines, and when a plume of smoke exhaled from Doniphon’s cigarette fills the screen, the scene defocuses (a postproduction optical printer effect), while swirling strings fill the soundtrack and the film dips to black.

The film flashes back, cutting from black screen to the black image of Doniphan’s back filling the camera frame. As he steps forward, the earlier action of Stoddard confronting Liberty Valance in the street is replaying, but shown now from Doniphon’s point of view where he stands in a darkened alley to the side of the confrontation (Figure 4.19).

Doniphon’s ranch hand Pompey (Woody Strode) tosses him a rifle as Valance taunts Stoddard and prepares to kill him. “This time, right between the eyes,” says Valance, cocking his pistol. As Stoddard fires wildly with his pistol, Doniphon fires his rifle from the alley, killing Valance, who stumbles out into the street. The flashback formally “bookends” its opening as Doniphon walks into camera, causing the screen to return to black, while a fade in returns us to the two men talking.

John Ford presents the shooting of Liberty Valance twice in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. It’s only when Doniphon takes Stoddard aside late in the film and tells him that he didn’t kill Valance that the “true” presentation of killing unfolds – the second version – where Doniphon shoots him from the alley nearby.48 As Bordwell points out, the Hollywood film can justify such replays when they bring to light new information, but without an authentic impetus in the story, the film’s narration becomes unrestricted and self-conscious, repeating portions of the syuzhet at will.49 It is a testament to the drive for narrative clarity in Hollywood films that the recounted enactment in Liberty Valance is marked by a push in, defocus, a string motif in the soundtrack, and a fade to black so that the viewer will clearly understand the flashback to follow. This convention of clearly marking flashbacks is such a common cinematic figure of style in classic Hollywood films that it is spoofed in Wayne’s World (Penelope Spheeris, 1992) when Wayne and Garth make wavy motions with their hands, and sing a silly trilling song as the film offers two alternate endings to the film. See Critical Commons, “Wayne’s World: Spoofing a Marked Temporal Reversal”50 The first alternate ending is identified by Garth as “the Scooby Doo ending,” a reference to the television cartoon franchise, because they unmask a character in that version, an action typical of the cartoon (Figure 4.20).

Figure 4.17 Shooting Liberty Valance: version 1. Ranse Stoddard (James Stewart) kills a local thug who terrorizes the town – Liberty Valance (Lee Marvin) – or so he thinks. The first version of the event is shown from Stoddard’s point of view.

Source: Copyright 1962 Paramount Pictures.

Figure 4.18 Shooting Liberty Valance: version 2, recounted enactment. A hybrid form of flashback is the recounted enactment, where a character begins telling an earlier narrative event . . .

Figure 4.19 Shooting Liberty Valance: new point of view.. . .and the film dissolves back in time to show that event. Here, the second version of the event is shown from Tom Doniphon’s (John Wayne) point of view.

Source: Copyright 1962 Paramount Pictures.

Figure 4.20 Wayne’s World: flashback spoof. The Hollywood convention of clearly marking flashbacks is spoofed when Wayne (Mike Myers) and Garth (Dana Carvey) make wavy motions with their hands to indicate a flashback.

Source: Copyright 1992 Paramount Pictures.

Narrative Functions of Manipulating Temporal Order

As we noted earlier, Bordwell’s theorizing about narration in fiction films takes the macro approach. He argues that, as the viewer interacts with the film text unfolding on the screen, temporal order is one of the primary ways to cue important story building activities in the viewer. These temporal manipulations in the syuzhet have significant effects on the viewer’s construction of the narrative because

- Adherence to fabula order concentrates the viewer’s thinking on upcoming events.

- Adherence to fabula order favors the primacy effect, a demonstrated psychological tendency for items presented first in a series to be remembered better or to be more influential than those presented later in the series. Meir Steinberg borrowed this term to describe how early knowledge created by the story forms an initial “frame of reference to which subsequent information [is] subordinated as far as possible.”51

- Reordering fabula events is the most common method of creating gaps in the narrative. Gaps are untold portions of the fabula: they are important to the process of narration because they maintain viewer interest, either by leaving out unnecessary narrative events or by focusing the viewers’ attention on what information is missing. Gaps in the story pointedly invite the viewer to frame expectations about upcoming story events.52

We will return to gaps below when we discuss temporal compression.

The Frequency of Narrative Events

Just as Bordwell lays out four possible cases for order of narrative events in fabula and syuzhet, he lays out a similar grid for all the possible cases of frequency of narrative events in fabula and syuzhet, using the “recounted/enactment” distinction we just looked at. He first notes that “The viewer presumes that fabula events are unique occurrences, but each one can be represented in the syuzhet any number of times. For convenience let us say that the syuzhet can represent fabula events once (1), more than once (1+), or not at all (0).” 53 Bordwell specifies further that a fabula event can be represented in two ways: by enacting it or by recounting is. Let’s get the simplest case out of the way first: when a film neither enacts nor recounts a narrative event (the “0” case) it relies solely on the viewer to infer it as we saw above: a man and woman kiss goodnight by the woman’s apartment door, cut to the man and woman the next morning lying in bed, and we infer they have had sex together. At a more mundane level, this is the ubiquitous case of elided events we noted in Chapter 2, where uninteresting events are not shown: a man talking on his cell phone says, “I’ll see you at the airport,” hangs up, and walks out his house. Cut to same man standing in an airline ticket line talking to his wife. If an event that has causal significance to the fabula occurred on the drive to the airport, it would ordinarily be recounted or enacted.

How does the syuzhet represent a fabula event once – the “1” case? One way is by enacting it once, a case exemplified by virtually all of pre-1908 cinema. Silent films enact every significant fabula event: nothing is left to infer. Kristin Thompson points out that “In the early films, there is virtually no difference between story events and the way they are presented in the plot. We seldom learn of any event we have not seen. . . In the primitive film, we seem often to have stumbled on characters we know little about, and we witness their actions out of context.”54 Likewise, representing a fabula event once by recounting it once is also common: a character explains their current behavior by telling of a prior event, thereby inscribing it to the syuzhet in a single instance.

How does the syuzhet represent a fabula event more than once – the “1+” case? This is infrequent in cinema, but we can think of examples where the multiple enactment of a fabula event is useful for thematic development and/or narrative development. In October: Ten Days that Shook the World (Eisenstein, 1928), Eisenstein presents the fall of the statue of Czar Alexander III twice, once in reverse, without any character recounting the event, a much more symbolic use of the shot, a striking visual figure of style.55 (We will discuss October’s use of intellectual montage in Chapter 5.) Multiple enactments can even be the foundation of a story, as in the film Groundhog Day (Ramis, 1993) where meteorologist Phil Connors (Bill Murray) finds himself in a time loop, reliving the eponymous event in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania.

Representing a fabula event more than once by recounting seems counterintuitive at first glance, but is actually common in classically narrated films, particularly in expository sequences. In the opening scene of The Maltese Falcon (Huston, 1941), for example, the private investigator Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) meets a prospective client Ruth Wonderly (Mary Astor) in his office, and she tells him that she is in San Francisco searching for her sister who she believes is with a man named Thursby. When Spade’s partner Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan) enters the office later in the scene, Spade gets him up to speed by recounting Wonderly’s tale of her search for her sister, a way for the syuzhet to concentrate and reinforce the narrative’s opening complication. See Critical Commons, “Maltese Falcon: Opening scene.”56 Instances where a film enacts an event once, and recounts it once or more than once are also common: an action seen in a film is often the topic of discussion among the characters. In La La Land (Chazelle, 2016) Mia (Emma Stone), an aspiring actress, writes and performs a one woman show. The show is an on-going topic of discussion with her love interest Sebastian (Ryan Gosling), a jazz pianist, both before and after its production, a form of repetition central to the plot since it ultimately becomes the event that launches her successful career.

Another interesting case of recounting and enacting more than once is the murder of Parnell “Stacks” Edwards (Samuel L. Jackson) in Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990). See “Goodfellas: Multiple Enactment, Single Recounting in the Murder of ‘Stacks.’ ”57 Stacks is part of the team that robs a Lufthansa shipment at John F. Kennedy International Airport, stealing $6 million, and his job is to get rid of the truck used in the heist. Instead he gets stoned, goes to his girlfriend’s house and the police find the truck. Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) and Frankie Carbone (Frank Sivero) are sent to kill Stacks. They bang on his door, wake him and enter his apartment. Tommy sends Frankie to make coffee, and makes small talk with Stacks, circling behind him, as he pulls on his clothes. Standing outside the frame, Tommy raises an immense automatic pistol with a silencer attached into foreground and fires, scattering Stacks’ brains across his bed in a moment of shocking violence. As the shooting continues, the film cuts to Frankie who comes into the bedroom doorway holding the coffee pot to see what has happened. They leave in a hurry, with Tommy first asking Frankie “Come on, make that coffee to go,” and then chiding him, “It’s a joke. A joke. Put the fucking pot down. We ain’t going to take the coffee.”

The film cuts to black as they close the door, and using staging that echoes Tom Doniphon’s stepping into frame in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (see Figure 4.18, p. 120), Tommy steps away from the lens (a “tail-away” shot), moving into frame. As he turns and begins to fire more shots in slow motion, (Figure 4.21) Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), the film’s narrator says in voice over, “Stacks was always crazy. Instead of getting rid of the truck like he was supposed to, he got stoned, went to his girlfriend’s, and by the time he woke up, the cops had found the truck. It was all over the television. They even said they came up with prints off the wheel. It was just a matter of time before they got to Stacks.” This last line falls over a high angle shot of Stacks’ bloody corpse lying on the floor next to his blood-splattered bed.

Figure 4.21 Goodfellas: multiple enactment, single recounting in the murder of “Stacks”. By avoiding the conventional Hollywood “flashback markers” and using slow motion, the frequency of the narrative event dominates in this immediate replay of Tommy (Joe Pesci) shooting Stacks (Samuel L. Jackson), like a football play that is dissected by a sports announcer.

Source: Copyright 1990 Warner Bros.

Clearly, the cut back to the slow motion shot of Tommy firing his gun is a flashback. And in Burch’s terms could be described as Case 7 Spatially Discontinuous Proximate (cut from the shot showing Stacks’ apartment door to Tommy entering frame in Stacks’ bedroom), Temporal Reversal Measureable (cut from the moment they leave the apartment to an event that happened seconds earlier). But the use of slow motion and a low camera angle, coupled with Henry Hill’s voice over and a 1960s do-wop love song added to the track, gives the viewer an immediate replay of the shooting, almost like a football play that is dissected by a sports announcer. The murder, abrupt and without warning, still “hangs in the air” as Tommy and Frankie leave the apartment, joking about “coffee to go.” The cognitive dissonance the murder creates in the viewer – Stacks is part of the heist team and Stacks is murdered by the team – is brilliantly resolved by the “slo-mo replay.” Bypassing the conventional Hollywood “flashback markers,” and not motivated by a character’s subjective memory, Goodfellas immediately replays the shooting, the slow motion rendering Tommy’s actions “formalized” and menacing like an avenging angel. Adding a somber voice over 14 seconds later into the flashback via the narrator Henry Hill, sets up the replay as more of an enacted recounting than a recounted enactment, and the murder is shown the second time in a new context, rather than motivated by the traditional, subjective, character memory.

The Duration of Narrative Events

Because pacing and rhythm are central to editing moving images, determining the duration of narrative events is a critical function of the editor. The editor asks of every shot, whether literally or intuitively, “What is the life of this shot?” i.e., how long can/should the film hold this shot? Questions of duration are critical to story comprehension, since under normal conditions, the viewer has no control of how long the narration takes to unfold. The editor’s choices regarding duration can challenge fabula formation with rapid, concentrated story information, discourage it by proceeding so slowly that the viewer loses interest, or encourage it with narration that proceeds at a pace that is “just right:” the viewer is engaged but neither bored nor overly challenged. Bordwell identifies three parameters of duration:

- the duration of the fabula or the overarching story

- the duration of the syuzhet or plot shown in the film

- the screen duration or “running time.”

Using this guide, the durations for Citizen Kane (Welles, 1941) sort out like this,

- fabula duration: from Kane as a boy of seven or eight playing in the snow in Colorado until a few days after his death when the reporters give up looking for the meaning of “Rosebud”

- syuzhet duration: the stretches of time – some from his lifetime, some after his death – that are actually dramatized in the film

- screen duration: 119 minutes.