Chapter 5

Digging Deeper into Your Ancestors’ Lives

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Using vital-records sources on the Internet

Using vital-records sources on the Internet

![]() Locating immigration databases

Locating immigration databases

![]() Assessing online land records

Assessing online land records

![]() Finding electronic military records

Finding electronic military records

![]() Searching tax-record sources

Searching tax-record sources

![]() Researching court records

Researching court records

As we all know, governments love paper. Sometimes it seems that government workers can’t do anything without a form. Luckily for genealogists, governments have been this way for many years — otherwise, it might be next to impossible to conduct family history research. In fact, the number of useful government records available online has exploded in the past decade. Not only have government entities been placing records and indexes online, but private companies have put great effort into digitizing and indexing government records for online use.

In this chapter, we show you what kinds of records are available and describe some of the major projects that you can use as keys for unlocking government treasure chests of genealogical information.

These Records Are Vital

It seems that some kind of government record accompanies every major event in our lives. One is generated when we are born, another when we get married (as well as get divorced), another when we have a child, and still another when we pass on. Vital records is the collective name for records of these events. Traditionally, these records have been kept at the local level — in the county, parish, or in some cases, the town where the event occurred. However, over time, some state-level government agencies began making an effort to collect and centralize the holdings of vital records.

Reading vital records

Vital records are among the first sets of primary sources typically used by genealogists (for more on primary sources, see Chapter 1). These records contain key and usually reliable information because they were produced near the time that the event occurred, and a witness to the event provided the information. (Outside the United States, vital records are often called civil registrations.) Four common types of vital records are birth records, marriage records, divorce records, and death records.

Birth records

Birth records are good primary sources for verifying the date of birth, birthplace, and names of an individual’s parents. Depending on the information requirements for a particular birth certificate, you may also discover the birthplace of the parents, their ages, occupations, addresses at the time of the birth, whether the mother had given birth previously, date of marriage of the parents, and the names and ages of any previous children.

Marriage records

Marriage records come in several forms. Early marriage records may include the following:

- Marriage bonds: Financial guarantees that a marriage was going to take place

- Marriage banns: Proclamations of the intent to marry someone in front of a church congregation

- Marriage licenses: Documents granting permission to marry

- Marriage records or certificates: Documents certifying the union of two people

These records usually contain the groom’s name, the bride’s name, and the location of the ceremony. They may also contain occupation information, birthplaces of the bride and groom, parents’ names and birthplaces, names of witnesses, and information on previous marriages.

Divorce records

One type of vital record that may be easy to overlook is a divorce decree. Later generations may not be aware that an early ancestor was divorced, and the records recounting the event can be difficult to find. However, divorce records can be valuable. They contain many important facts, including the age of the petitioners, birthplace, address, occupations, names and ages of children, property, and the grounds for the divorce.

Death records

Death records are excellent resources for verifying the date of death but are less reliable for other data elements such as birth date and birthplace because people who were not witnesses to the birth often supply that information. However, information on the death record can point you in the right direction for records to verify other events. More recent death records include the name of the individual, place of death, residence, parents’ names, spouse’s name, occupation, and cause of death. Early death records may contain only the date of death, cause, and residence.

Gauging vitals online

Historically, researchers were required to contact the county, parish, or town clerk to receive a copy of a vital record. This meant either traveling to the location where the record was housed or ordering the record through the mail. With the advent of online research, most sites covering vital records are geared toward providing addresses of repositories, rather than information on the vital records of particular individuals. The reason for this is the traditional sensitivity of vital records — and the reluctance of repositories to place vital records online due to identity theft and privacy concerns.

A few years ago, the number of resources containing information about specific vital records, including indexes and digitized records, began to greatly increase. Today, the vast majority of resources are indexes to vital records, but digitized records are starting to appear more frequently.

To get a better idea of how to search for vital records, we will try to locate records to fill in the missing information on William Henry Abell that we began researching in Chapter 2.

The best source to verify your research is a copy of the actual vital record. Digitization of vital records has boomed over the past few years. Initially, archives that house vital records were reluctant to digitize them due to privacy concerns. However, as more and more requests came in for vital records, these archives have allowed companies to place those records that fall outside the provisions of the privacy act online. If you can’t find a copy of the vital record online, then the next best thing is an index that can point you to where the record is located. Then you can request a copy of the record.

There are a few strategies for finding vital record information online. You can use a search engine, a comprehensive genealogical index, or a Wiki page with links to online vital records resources.

We know from our research in Chapter 2 that William Henry Abell’s obituary stated that he died on 7 September 1955 in Hodgenville, Kentucky at the age of 82. To prove that the information in the obituary is true, we want to locate his death certificate — that might also provide more information than what was in the obituary.

We start with a quick trip to a search engine.

-

Go to the search engine Google (

www.google.com) and type the search term Kentucky death records and click the Google Search button.You might prefer to use a different state name, depending on whether your ancestor was from Kentucky or somewhere else. The results page appears with links to several vital records sites.

-

Click the Kentucky, Death Records, 1852–1963 — Ancestry.com link.

We chose this link because William’s death was in 1955 and the description of the site indicated original records. The resulting screen includes a search form requesting information.

-

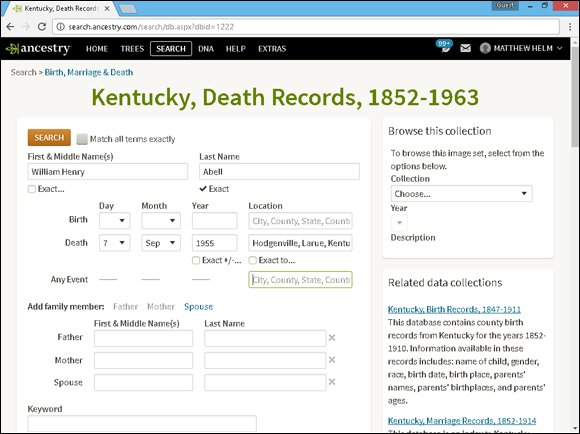

Type William Henry in the First & Middle Name(s) field and Abell in the Last Name field, enter 7 Sep 1955 and Hodgenville, Kentucky in the Death field, and then click the Search button; see Figure 5-1.

Again, you might want to substitute your own ancestors’ names. If so, your results will vary a bit. A table containing three search results is displayed. The top result contains a record for William H. Abell with a birth dated of 17 January 1873 and a death date of 07 September 1955 in Larue, Kentucky.

-

Click the icon on the far right of the row in the View Images column.

A page appears with subscription information. If you already have a subscription, you can log in to your account at the upper-right corner of the screen. If not, you have to follow the prompts to get a free 14-day trial. We fill in the login information and click the Sign In button. After the login, the page displays the image of the death record.

-

After the image pops up, click the Zoom In button to see the image more clearly.

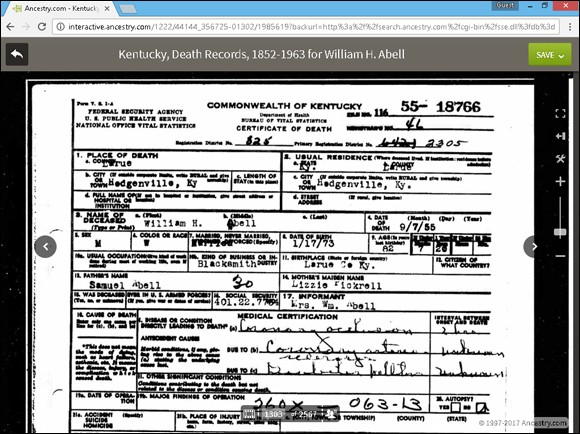

Figure 5-2 shows the image of the death record.

FIGURE 5-1: The search form for the Kentucky Death Records collection at Ancestry.com.

FIGURE 5-2: Image recording the death of William Henry Abell.

You can find a number of vital records and civil registration resources at the Ancestry.com and MyHeritage (www.myheritage.com) subscription sites. The free site FamilySearch.org also contains several collections.

If you’ve had only a little luck finding a digitized vital record or index (or you need a record that falls within the range of the privacy act), your next step might be to visit a general information site. If you’re looking for information on how to order vital records in the U.S., you can choose among a few sites. Several commercial sites have addresses for vital records repositories. Unfortunately, some of them are full of advertisements for subscription sites, making it difficult to determine which links will lead you to useful information and what is going to lead you to a third-party site that wants to make a sale.

One site that contains useful information without the advertisements is the Where to Write for Vital Records page on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention site (www.cdc.gov/nchs/w2w.htm). To locate information, simply click a state and you see a table listing details on how to order records from state-level repositories.

Investigating Immigration and Naturalization Records

You may have heard the old stories about your great-great-grandparents who left their homeland in search of a more prosperous life. Some of these stories may include details about where they were born and how they arrived at their new home. Although these are interesting and often entertaining stories, as a family historian, you want to verify this information with documentation.

Often the document you’re looking for is an immigration or naturalization record. Immigration records are documents that show when a person moved to a particular country to reside. They include passenger lists and port-entry records for ships, and border-crossing papers for land entry into a country. Naturalization records are documents showing that a person became a citizen of a country without being born in that country. Sometimes an immigrant will reside in a country without becoming a naturalized citizen, and you can find paperwork on him or her, too. You can look for alien registration paperwork and visas. A visa is a document permitting a noncitizen to live or travel in a country.

Immigration and naturalization documents can prove challenging to find, especially if you don’t know where to begin looking. Unless you have some evidence in your attic or have a reliable family account of the immigration, you may need a record or something else to point you in the right direction. Census records are useful. (For more information about census records, see Chapter 4.) Depending on the year your ancestors immigrated, census records may contain the location of birth and tell you the year of immigration and the year of naturalization of your immigrant ancestor.

Emigration records — documents that reflect when a person moved out of a particular country to take up residence elsewhere — are also useful to researchers. You find these records in the country your ancestor left. They can often help when you can’t find immigration or naturalization records in the new country.

Although locating immigration, emigration, and naturalization records online has been challenging in the past, it’s a growing field and more is available than ever. Common types of records that genealogists use to locate immigrants — passenger lists, immigration papers, and emigration records — have increased in availability on the Internet over the past decade and will likely continue to increase in numbers. A good starting point for determining an ancestor’s homeland is to look at census records. (Again, for more information about census records, see Chapter 4.) Because a great deal of early immigration and naturalization processing occurred at the local level, census records may give you an indication of where to look for immigration records.

Some examples of online records, indexes, and databases include the following:

- McLean County Circuit Clerk: McLean County, Illinois, Immigration Records (

www.mcleancountyil.gov/index.aspx?NID=161) - MayflowerHistory.com: Mayflower Passenger List (

http://mayflowerhistory.com/mayflower-passenger-list/) - Iron Range Research Center: 1918 Minnesota Alien Registration Records (

www.ironrangeresearchcenter.org)

Although the number of websites offering immigration and naturalization records has grown substantially, it’s still kind of hit and miss whether you’ll find an independent site that has what you need. You’re more likely to have success at one of the major subscription sites, like Ancestry.com or MyHeritage.

Ancestry.com’s Immigration and Travel records include over 500 collections sorted into passenger lists, crew lists, border crossings and passports, citizenship and naturalization, immigration and emigration books, and ship pictures and descriptions.

MyHeritage (www.myheritage.com) also hosts records under their Immigration and Travel collection. These include passenger lists, citizenship and naturalization, immigration and emigration, and immigration documents. You can find the search form for this collection at https://www.myheritage.com/research/category-4000/immigration-travel?formId=immigration-norels&formMode=&action=showForm.

FamilySearch.org contains over 190 databases within their Migration and Naturalization collection. These include both domestic and foreign immigration record sets. For a list of available databases, see https://familysearch.org/search/collection/list/?page=1&recordType=Migration.

Passenger lists

One type of immigration record that you can find on the Web is passenger lists. Passenger lists are manifests of who traveled on a particular ship. You can use passenger lists not only to see who immigrated on a particular ship, but you can also see citizens of the U.S. who were merely traveling by ship (perhaps coming back from vacation in Europe).

A source for passenger lists is the Immigrant Ships Transcribers Guild passenger-list transcription project (www.immigrantships.net). Currently, the guild has transcribed more than 17,000 passenger manifests. The passenger lists are organized by date, ship’s name, port of departure, port of arrival, passenger’s surname, and captain’s name. You can also search the site to find the person or ship that interests you. Other pages containing links to passenger lists include:

- Rootsweb.com Passenger Lists:

http://userdb.rootsweb.ancestry.com/passenger/ - Castle Garden (the precursor to Ellis Island):

www.castlegarden.org - Famine Irish Passenger Record Data File:

http://aad.archives.gov/aad/fielded-search.jsp?dt=180&tf=F&cat=SB302&bc=sb,sl - Ship Passenger List Index for New Netherland:

www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~nycoloni/nnimmdex.html - Boston Passenger Manifests (1848–1891):

www.sec.state.ma.us/arc/arcsrch/PassengerManifestSearchContents.html - Maine Passenger Lists:

www.mainegenealogy.net/passenger_search.asp - Partial Transcription of Inward Slave Manifests:

www.afrigeneas.com/slavedata/manifests.html - Maritime Heritage Project: San Francisco:

www.maritimeheritage.org/passengers/index.html - Galveston Immigration Database:

www.galvestonhistory.org/attractions/maritime-heritage/galveston-immigration-database

If you know (or even suspect) that your family came through Ellis Island, one of your first stops should be the Ellis Island Foundation site. The site contains a collection of 25 million passengers, along with ship manifests and images of certain ships.

To illustrate how the Ellis Island Foundation site works, look for Harry Houdini, who passed through the port a few times. Use these steps to search for Harry Houdini and see the results:

-

Go to the Ellis Island site at

www.libertyellisfoundation.org.The search box is located just under the main header.

-

Type the passenger’s name in the search boxes and click Find Passenger.

You should see a results box with the name of the passenger, residence (if stated), arrival year, and some links to the passenger record, ship manifest, and the ship’s image (if available).

For our example, we type Harry in the Passenger’s First Name field, and Houdini in the Passenger’s Last Name field. When we click Start Search, we get a list of three results — entries for travel in 1911, 1914, and 1920.

-

Click the ship manifest link for the 1920 record.

When you click the link to see the ship manifest, the Ellis Island site advises that you must be a registered user.

-

If you’re already a member, follow the prompts to sign in, and then go to Step 6. If you’re not yet a member, click the Create a Free Account link and go to Step 5.

Registration is free and takes only a few minutes.

-

Complete the online membership registration form, then click Continue.

You must provide your first name, last name, email address, password (which has very specific requirements), country, postal code, security question/answer, click the checkbox for the terms and conditions, and enter the captcha code (letter and number combination).

-

Review the information about this manifest.

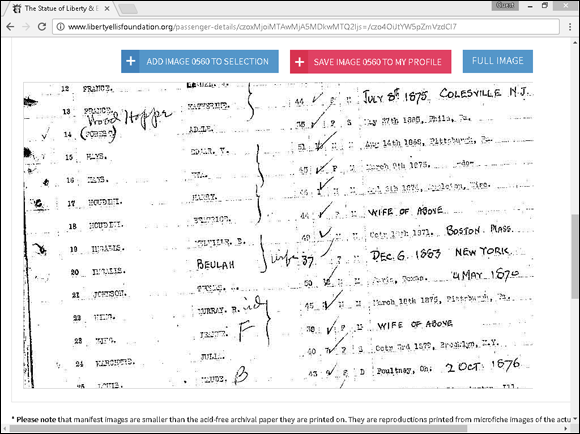

Figure 5-3 shows the manifest for the ship Imperator that sailed from Southampton on July 3, 1920 and arrived on July 11, 1920. If you scroll through the manifest online, you can see that Harry was traveling with his wife.

FIGURE 5-3: Harry Houdini’s entry in a passenger list at the Ellis Island site.

Naturalization records

The road to citizenship was paved with paper, which is a good thing for researchers. On the Fold3 site (www.fold3.com), you can find naturalization records housed in the National Archives online. Figure 5-4 shows a naturalization record from Fold3.

FIGURE 5-4: A naturalization petition at Fold3.

Fold3 has more than 7.6 million naturalization records that you can search or browse by location and last name. Some of the collections include

- Naturalization Petitions for the Southern District of California, 1887–1940

- Records of the U.S. Circuit Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, New Orleans Division: Petitions, 1838–1861

- Petitions and Records of Naturalizations of the U.S. District and Circuit Courts of the District of Massachusetts, 1906–1929

- Naturalization Petitions of the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland, 1906–1930

- Naturalization Petitions for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 1795–1930

- Naturalization Petitions of the U.S. Circuit and District Courts for the Middle District of Pennsylvania, 1906–1930

- Naturalization Petitions of the U.S. District Court, 1820–1930, and Circuit Court, 1820–1911, for the Western District of Pennsylvania

- Index to Naturalizations of World War I Soldiers, 1918

For more about Fold3 and all its records, flip back to Chapter 3.

You can also find some database indexes of naturalizations online. Here are some examples:

- Arkansas: Arkansas Naturalization Records Index, 1809–1906, at

www.naturalizationrecords.com/usa/ar_natrecind-a.shtml - California: Index to Naturalization Records in Sonoma County, California, 1841–1906, at

www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~cascgs/nat.htm - California: Index to Naturalization Records in Sonoma County, California, Volume II, 1906–1930, at

www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~cascgs/nat2.htm - Colorado: Colorado State Archives Naturalization Records at

www.colorado.gov/pacific/archives/naturalization-records - Delaware: Naturalization Records Database at

http://archives.delaware.gov/collections/natrlzndb/nat-index.shtml - Indiana: Archives and Records Administration’s Naturalization Index at

www.in.gov/serv/iara_naturalization - Missouri: Naturalization Records, 1816–1955, at

https://s1.sos.mo.gov/records/archives/archivesdb/naturalization - New York: Italian Genealogical Group page on New York and New Jersey Naturlizations at

www.italiangen.org/records-search/naturalizations.php - North Dakota: North Dakota Naturalization Records Index at

https://library.ndsu.edu/db/naturalization - Ohio: Miami County Naturalization Papers, 1860–1872, at

www.thetroyhistoricalsociety.org/m-county/natural.htm - Pennsylvania: Centre County Naturalization Records, 1802–1929, (includes images of the records) at

http://co.centre.pa.us/centreco/hrip/natrecs/default.asp - Washington: Digital Archives at

www.digitalarchives.wa.gov/default.aspx

Land Ho! Researching Land Records

In the past, an individual’s success was often measured by the ownership of land. The more land your ancestors possessed, the more powerful and wealthy they were. This concept encouraged people to migrate to new countries in the quest to obtain land.

In addition to giving you information about the property your ancestor owned, land records may tell you where your ancestor lived before purchasing the land, the spouse’s name, and the names of children, grandchildren, parents, or siblings. To use land records effectively, however, you need to have a general idea of where your ancestors lived and possess a little background information on the history of the areas in which they lived. Land records are especially useful for tracking the migration of families in the U.S. before the 1790 census.

Most land records are maintained at the local level — in the town, county, or parish where the property was located. Getting a foundation in the history of land records before conducting a lot of research is a good idea because the practices of land transfers differed by location and time period. A good place to begin your research is at the Land Record Reference page at www.directlinesoftware.com/landref.htm. This page contains links to articles on patents and grants, bounty lands, the Homestead Act, property description methods, and how land transactions were conducted. For a more general treatment of land records, see “Land Records,” by Sandra Hargreaves Luebking, in The Source: A Guidebook to American Genealogy, Third Edition, edited by Loretto Dennis Szucs and Luebking (https://www.ancestry.com/wiki/index.php?title=Overview_of_Land_Records).

Surveying land lovers in the U.S.

Land resources are among the most plentiful sources of information on your ancestors in the U.S. Although a census would have occurred only once every ten years on average, land transactions may have taken place multiple times during that decade, depending on how much land your ancestor possessed. These records don’t always contain a great deal of demographic information, but they do place your ancestor in a time and location, and sometimes in a historical context as well. For example, you may discover that your ancestors were granted military bounty lands. This discovery may tell you where and when your ancestors acquired the land, as well as what war they fought in. You may also find out how litigious your ancestors were by the number of lawsuits they filed or had filed against them as a result of land claims.

Your ancestors may have received land in the early U.S. in several ways. Knowing more about the ways in which people acquired land historically can aid you in your research.

Your ancestor may have purchased land or received a grant of land in the public domain — often called bounty lands — in exchange for military service or some other service for the country. Either way, the process probably started when your ancestor petitioned (or submitted an application) for the land. Your ancestor may have also laid claim to the land, rather than petitioning for it.

If the application was approved, your ancestor was given a warrant — a certificate that allowed him or her to receive an amount of land. (Sometimes a warrant was called a right.) After your ancestor presented the warrant to a land office, an individual was appointed to make a survey — a detailed drawing and legal description of the boundaries — of the land. The land office then recorded your ancestor’s name and information from the survey into a tract book (a book describing the lots within a township or other geographic area) and on a plat map (a map of lots within a tract).

After the land was recorded in the tract book, your ancestors may have been required to meet certain conditions, such as living on the land for a certain period of time or making payments on the land. After they met the requirements, they were eligible for a patent — a document that conveyed title of the land to the new owner.

If your ancestors received bounty lands in the U.S., you might be in luck. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM), General Land Office Records (https://glorecords.blm.gov/default.aspx) holds more than 5 million federal land title records issued between 1820 and the present, and images of survey plats and field notes from 1810.

Follow these steps to search the records on this site:

- Go to the Official Federal Land Records site (

https://glorecords.blm.gov/default.aspx). -

In the green bar at the top of the page, click Search Documents.

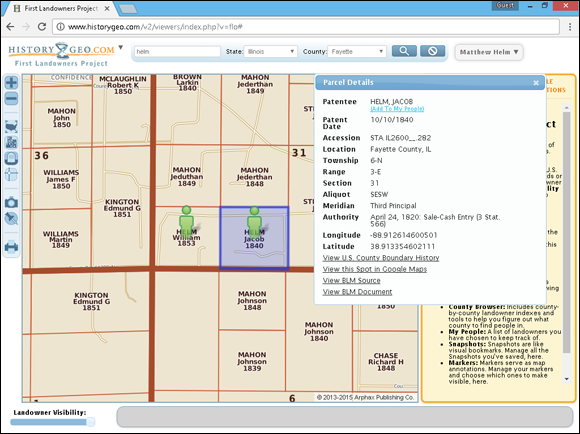

This brings you to a search form that you can fill out to search all of the contents at the BLM site. Matthew’s interest, for example, is in finding land that one of his ancestors, Jacob Helm, owned in Illinois.

-

Click the Search Documents by Type tab on the top of the form.

The other tabs are Search Document by Location and Search Documents by Identifier.

-

Click Patents on the left side of the form.

The other options are Surveys, LSR (Land Status Records), and CDI (Control Document Index).

-

In the Locations section of the form, use the drop-down list to select a state and, if desired, a county.

For our example, we select Illinois for the State field, and use the default Any County in the County field.

-

In the Names section of the form, type a last name and first name in the appropriate fields.

We type Helm in the Last Name field and Jacob in the First Name field.

-

If you have other criteria for your search that fits in the Land Description or Miscellaneous sections, you can enter it now.

For our example, we don’t know much else than the state and name, so we don’t provide any other search criteria.

-

Click the Search Patents button at the bottom of the form.

The results list generates.

-

Scroll through the results and choose one that looks promising. If you want to go directly to the image of the document, click the Image icon. But if you want additional information about the record, click the Accession link.

We want as much information about the record as possible, so we click the Accession link for the single result for Jacob Helm in Illinois. This opens a page with three tabs: Patent Details, Patent Image, and Related Documents.

-

The view defaults to the Patent Details tab. Review the information provided.

Depending on the specific record, this detailed entry provides information such as name on the patent, the land office involved, mineral rights, military rank, document numbers, survey data, and a land description.

-

Click the Patent Image tab to view a digitized copy of the patent.

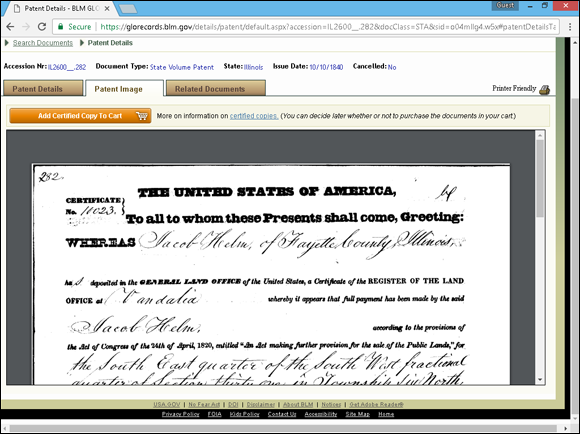

You can view the document as a PDF within the frame. We can then save the copy of the document on your computer. Figure 5-5 shows the patent for Jacob Helm.

-

If you’re interested in learning about your ancestor’s neighbors, click the Related Documents tab.

A list of other documents with the same land description — township, range, and section — generates. You can use this list to see who your ancestor’s neighbors were and learn more about them.

FIGURE 5-5: The land patent for Jacob Helm at the General Land Office site.

For secondary land transactions (those made after the original grant of land), you probably need to contact the recorder of deeds for the county in which the land was held. Several online sites contain indexes to land transactions in the U.S. Some of these are free, and other broader collections require a subscription. The easiest way to find these sites is to consult a comprehensive genealogical index site and look under the appropriate geographical area. In a land index, you’re likely to encounter the name of the purchaser or warrantee, the name of the buyer (if applicable), the location of the land, the number of acres, and the date of the land transfer. In some cases, you may see the residence of the person who acquired the land.

Here are some websites with information on land records:

- Legal Land Descriptions in the USA:

http://illinois.outfitters.com/genealogy/land/ - Alabama: Land Records at

http://sos.alabama.gov/government-records/land-records - Arkansas: Land Records at

http://searches.rootsweb.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/arkland/arkland.pl - California: Early Sonoma County, California, Land Grants, 1846–1850, at

www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~cascgs/intro.htm - Illinois: Illinois Public Domain Land Tract Sales at

www.ilsos.gov/isa/landsrch.jsp - Indiana: Land Records at the State Archives at

www.in.gov/iara/2585.htm - Louisiana: Office of State Lands at

www.doa.la.gov/Pages/osl/Index.aspx - Maryland: Land Records in Maryland at

http://guide.mdsa.net/pages/viewer.aspx?page=mdlandrecords - New York: Ulster County Deed Books 1, 2 & 3 Index at

http://archives.co.ulster.ny.us/deedsearchscreen.htm - North Carolina: Alamance County Land Grant Recipients at

www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~ncacgs/ala_nc_land_grants.html - Ohio: Introduction to Ohio Land History at

www.directlinesoftware.com/ohio.htm - Oregon: Oregon State Archives Land Records at

http://sos.oregon.gov/archives/Pages/records/aids-land.aspx - Texas: Texas General Land Office Archives at

www.glo.texas.gov/ - Wisconsin: Wisconsin Public Land Survey Records: Original Field Notes and Plat Maps at

http://digicoll.library.wisc.edu/SurveyNotes

In addition to the methods we mention in this section, you may want to check out geography-related resources, such as The USGenWeb Project (www.usgenweb.org) or the WorldGenWeb Project (www.worldgenweb.org). These sites organize their resources by location (country, state, county, or all three, depending on which you use). Of course, if your attempts to find land records and information through comprehensive sites and geography-related sites don’t prove as fruitful as you’d like, you can always turn to a search engine such Google (www.google.com).

Using HistoryGeo.com to map your ancestor’s land

HistoryGeo.com is a subscription site that focuses on land records. It contains two collections. The First Landowners Project allows users to see more than 9 million landowners’ names and information on one master map. The project covers 21 states. The antique maps collection contains over 4000 maps and atlases.

The First Landowners Project enables you to search by surname the original owners of public lands in the U.S. You can also restrict the search by state and county, if desired. In examining this site, we search for Matthew’s ancestor, Jacob Helm, in Illinois. The results contain numerous Helms, but we know Jacob lived in Fayette County, so we home in on him and his brother rather quickly; see Figure 5-6. Then, by clicking the green person icon, we see details about the land parcel and even connect to an image of the original Bureau of Land Management document.

FIGURE 5-6: The First Landowners Project map showing Jacob Helm’s land and the Parcel Details for that land.

In addition to being able to see information about the piece of land, you can add markers on the map to indicate events in your ancestors’ lives, save people to your list of favorites, and plot migration patterns for multiple ancestors or families at a time.

Marching to a Different Drummer: Searching for Military Records

Although your ancestors may not have marched to a different drummer, at least one of them probably kept pace with a military beat at some point. Military records contain a variety of information. The major types of records that you’re likely to find are service, pension, and bounty land records. Draft or conscription records may also surface in your exploration.

Service records chronicle the military career of an individual. They often contain details about where your ancestors lived, when they enlisted or were drafted (or conscripted, enrolled for compulsory service), their ages, their discharge dates, and in some instances, their birthplaces and occupations. You may also find pay records (including muster records that state when your ancestors had to report to military units) and notes on any injuries that they sustained while serving in the military. You can use these records to determine the unit in which your ancestor served and the time periods of their service.

This information can lead you to pension records that can contain significant genealogical information because of the level of detail required to prove service to receive a pension. Service records can give you an appreciation of your ancestor’s place within history — especially the dates and places where your ancestor fought or served as a member of the armed forces.

Pensions were often granted to veterans who were disabled or who demonstrated financial need after service in a particular war or campaign; widows or orphans of veterans also may have received benefits. These records are valuable because, to receive pensions, your ancestors had to prove that they served in the military. Proof entailed a discharge certificate or the sworn testimony of the veteran and witnesses. Pieces of information that you can find in pension records include your ancestor’s rank, period of service, unit, residence at the time of the pension application, age, marriage date, spouse’s name, names of children, and the nature of the veteran’s financial need or disability. If a widow submitted a pension application, you may also find records verifying her marriage to the veteran and death records (depending on when the veteran ancestor died).

Bounty lands were lands granted by the government in exchange for military service that occurred between 1775 and 1855. Wars covered during this period include the American Revolution, War of 1812, Old Indian Wars, and the Mexican Wars. To receive bounty lands, soldiers were required to file an application. These applications often contain information useful to genealogical researchers.

If you’re new to researching U.S. military records, take a look at the Research in Military Records page at the National Archives site (www.archives.gov/research/military/index.html). It contains information on the types of military records held by the archives, how you can use them in your research, and information on records for specific wars. Also, for the historical context of the time period that your ancestor served, see the U.S. Army Center of Military History Research Material page at www.history.army.mil/html/bookshelves/resmat/index.html. This site contains links to chapters from American Military History, which covers military actions from the Colonial period through the war on terrorism.

The largest collections for military records are currently housed in subscription sites. Here we give you a quick rundown on what several subscription sites have within their collections.

Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com) partnered with the National Archives to place digitized images of microfilm (held by the archives) online. As a result, most of the military records on Fold3 are federal. Here are some examples of available record sets:

- Navy Casualty Reports, 1776–1941

- Service Records of Volunteers, 1784–1811

- Revolutionary War Service and Imprisonment Cards

- War of 1812 Pension Files

- War of 1812 Society Applications

- Letters Received by the Adjutant General, 1822–1860

- Mexican War Service Records

- Civil War and Later Veterans Pension Index

- Confederate Amnesty Papers

- Spanish-American War Service Record Index

- Confidential Correspondence of the Navy, 1919–1927

- Foreign Burial of American War Dead

- Naturalization Index — WWI Soldiers

- Military Intelligence Division — Negro Subversion

- Missing Air Crew Reports, WWII

- WWII War Diaries

- Korean War Casualties

- Vietnam Service Awards

- Navy Cruise Books, 1918–2009

Ancestry.com (www.ancestry.com) has more than 1,200 collections of military records. Its collections include records for servicemen from the U.S. and several other countries. These military collections include

- World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918

- Sons of the American Revolution Membership Applications, 1889–1970

- U.S. Revolutionary War Miscellaneous Records (Manuscript File), 1775–1790s

- U.S. Civil War Soldiers, 1861–1865

- Confederate Service Records, 1861–1865

- Civil War Prisoner of War Records, 1861–1865

- U.S. Colored Troops Military Service Records, 1863–1865

- U.S. Marine Corps Muster Rolls, 1798–1958

- World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918

- U.S. World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938–1946

- British Army WWI Service Records, 1914–1920

- British Army WWI Medal Rolls Index Cards, 1914–1920

- British Army WWI Pension Records, 1914–1920

- Germany & Austria Directories of Military and Marine Officers, 1500–1939

- Canada War Graves Registers (Circumstances of Casualty), 1914–1948

- Canada Loyalist Claims, 1776–1835

- New Zealand Army WWII Nominal Rolls, 1939–1948

At WorldVitalRecords.com (http://worldvitalrecords.com), you can find over 1,500 military collections, including:

- List of Officials, Civil, Military, and Ecclesiastical of Connecticut Colony, 1636–1677

- Spanish American War Volunteers — Colorado

- Korean War Casualties

- Army Casualties 1956–2003

- Muster Rolls of the Soldiers of the War of 1812: Detached from the Militia of North Carolina in 1812 and 1814

And, if the big military collections don’t quite meet your needs, here is a sampling of the different records that are available on free sites:

- Muster Rolls and Other Records of Service of Maryland Troops in the American Revolution:

www.msa.md.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000018/html/index.html - Illinois Black Hawk War Veterans Database:

www.cyberdriveillinois.com/departments/archives/databases/blkhawk.html - South Carolina Records of Confederate Veterans 1909–1973:

www.archivesindex.sc.gov - National World War II Memorial Registry:

www.wwiimemorial.com/Registry/Default.aspx

Another set of valuable resources for researching an ancestor that participated in a war is information provided by a lineage society. Some examples include:

- Daughters of the American Revolution (

www.dar.org) - Sons of the American Revolution (

www.sar.org) - Society of the Cincinnati (

www.societyofthecincinnati.org) - United Empire Loyalists’ Association of Canada (

www.uelac.org) - National Society United States Daughters of 1812 (

www.usdaughters1812.org) - Daughters of Union Veterans of the Civil War (

www.duvcw.org) - Sons of Confederate Veterans (

www.scv.org)

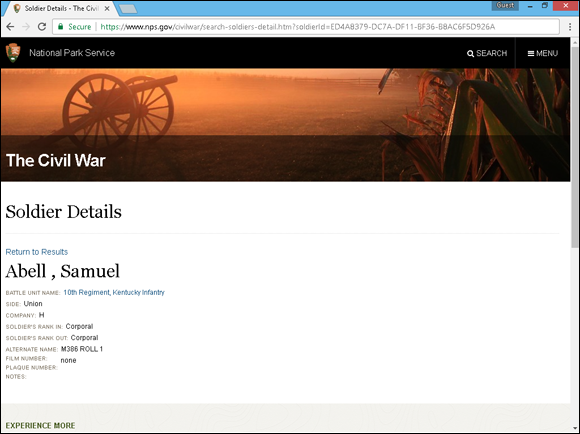

One collection of military records at a free site is the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System (CWSS). The CWSS site (https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm) is a joint project of the National Park Service, the Genealogical Society of Utah, and the Federation of Genealogical Societies. The site contains an index of more than 6.3 million soldier records of both Union and Confederate soldiers. Also available at the site are regimental histories and descriptions of 384 battles.

Follow these steps to search the records on this site:

-

Point your browser to the Civil War Soldier and Sailors System (

https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/soldiers-and-sailors-database.htm).On the page are boxes with links to Soldiers, Sailors, Regiments, Cemeteries, Battles, Prisoners, Medals of Honor, and Monuments.

-

Click the appropriate box for the person you’re looking for.

We’re looking for a soldier who served, so we click the Soldier box.

-

Type the name of the soldier or sailor in the appropriate field and click Search.

If you know additional details, you can select the side on which your ancestor fought, the state they were from, and rank. We typed Abell in the Last Name field, Samuel in the First Name field, Kentucky in the By State field, and Union in the By side field. Two search results appeared with that information.

-

Review your results and click the name of the soldier or sailor to see the Detailed Soldier Record.

The soldier details show that Samuel served in Company H, 10th Regiment, Kentucky Infantry; see Figure 5-7. He entered and left the service as a corporal. His information is located on National Archives series M386 microfilm, roll 1.

FIGURE 5-7: Detailed soldier record from the Civil War Soldiers and Sailors System.

Taxation with Notation

Some of the oldest records available for research are tax records — including property and inheritance records. Although some local governments have placed tax records online, these records are usually very recent documents rather than historical tax records. Most early tax records you encounter were likely collected locally (that is, at the county level). However, many local tax records have since been turned over to state or county archives — some of which now make tax records available on microfilm, as do Family History Centers. (If you have a Family History Center in your area, you may be able to save yourself a trip, call, or letter to the state archives — check with the Family History Center to see whether it keeps copies of tax records for the area in which you’re interested.) And a few maintainers of tax records — including archives and Family History Centers — are starting to make information about their holdings available online. Generally, either indexes or transcriptions of these microfilm records are what you find online. Another source for tax information are newspapers. Localities sometimes published tax assessment information in newspapers annually. We’ll look at online sources for newspapers later in this chapter.

Additionally, both Ancestry.com and FamilySearch have some tax records available through their sites. We explore how to use both of these sites in Chapter 3.

Here are just a few examples of the types of resources that you can find pertaining to tax records:

- Tax List: 1790 and1800 County Tax Lists of Virginia at

www.binnsgenealogy.com/VirginiaTaxListCensuses - Tax List: Territory of Colorado Tax Assessment Lists, 1862–1866, at

http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/ref/collection/p16079coll15/id/1976 - Land and Poll Tax: Benton County, Tennessee 1836 Land and Poll Tax List at

www.tngenweb.org/benton/databas2.htm

If you’re locating records in the U.S., try USGenWeb for the state or county. Here’s what to do:

- Go to the USGenWeb site (

www.usgenweb.org). -

Click a state in the map at the top of the page.

We click the Pennsylvania link because we’re looking for tax records in Lancaster County.

As a shortcut, you can always get to any USGenWeb state page by substituting the two-letter state code for the ‘us’ in

As a shortcut, you can always get to any USGenWeb state page by substituting the two-letter state code for the ‘us’ in www.usgenweb.org. For example, for Pennsylvania, you could typewww.pagenweb.org. -

From the USGenWeb state page (for the state that you choose), find a link to the county in which you’re interested.

On the Pennsylvania Counties page, we click the Pensylvania Counties menu item and then the Lancaster link to get to the Lancaster County GenWeb site.

-

Scroll through the main page for the state you’ve selected and click any tax-related links that look promising.

We clicked the link for Proprietary and State Tax Lists of the County of Lancaster for the Years 1771, 1772, 1773, 1779, and 1782; edited by William Henry Egle, M.D. (1898) under the Documents section.

The state and county websites in the USGenWeb Project vary immensely. Some have more information available than the Pennsylvania and Lancaster County pages, while others have less. The amount of information that’s available at a particular USGenWeb site affects the number of links you have to click through to find what you’re looking for. Don’t be afraid to take a little time to explore and become familiar with the sites for the states and counties in which your ancestors lived.

Trial and Error at the Courthouse

Do you have an ancestor who was on the wrong side of the law? If so, you may find some colorful information at the courthouse in the civil and criminal court records. Even if you don’t have an ancestor with a law-breaking past, you can find valuable genealogical records at your local courthouse, given that even upstanding citizens may have civil records on file or may have been called as witnesses. Typical records you can find there include land deeds, birth and death certificates, divorce decrees, wills and probate records, tax records, and some military records (provided the ancestors who were veterans deposited their records locally).

Court cases and trials aren’t just a phenomenon of today’s world. Your ancestor may have participated in the judicial system as a plaintiff, defendant, or witness. Some court records can provide a glimpse into the character of your ancestors — whether they were frequently on trial for misbehavior or called as character witnesses. You can also find a lot of information on your ancestors if they were involved in land disputes — a common problem in some areas where land transferred hands often. Again, your ancestor may not have been directly involved in a dispute but may have been called as a witness. Another type of court record that may involve your ancestor is a probate case. Often, members of families contested wills or were called upon as executors or witnesses, and the resulting file of testimonies and rulings can be found in a probate record. Court records may also reflect appointments of ancestors to positions of public trust such as sheriff, inspector of tobacco, and justice of the peace.

Finding court records online can be tricky. They can be found using a subscription database service or a general search engine, such as Bing (www.bing.com). Note, however, that good data can also be tucked away inside free databases that are not indexed by search engines. In this case, you will have to search on a general term such as Berks County wills or Berks County court records. Here is an example:

-

Go to the Bing search engine site (

www.bing.com).The search box is near the top of the page.

-

Type your search terms in the search box and click the Search icon (magnifying glass) or press Enter.

The results page is displayed. We type Berks County wills and received 89,700 results. Please note that this number changes often as new sites are added to the database. If the number of results you get is too large to reasonably sort through, you can narrow your search with additional terms, such as specific years or town names.

-

Click a link that looks relevant to your search.

We select the link to the Berks County Register of Wills at

www.co.berks.pa.us/rwills/site/default.asp. This site contains a database where you can search more than 1 million records covering a variety of areas, including birth, death, marriage, and estate.

Here are some sites to give you an idea of court records that you can find online:

- Missouri’s Judicial Records:

https://s1.sos.mo.gov/records/archives/archivesdb/judicialrecords/ - Atlantic County Library System’s Historic Resources Digitized Wills:

www.atlanticlibrary.org/historical_resources - Earl K. Long Library, The University of New Orleans Historical Archives of the Supreme Court of Louisiana:

http://libweb.uno.edu/jspui/handle/123456789/1 - The Proceedings of the Old Bailey: London’s Central Criminal Court, 1674 to 1913:

www.oldbaileyonline.org

Getting the News on Your Ancestors

A friend of ours has a great story — morbid as it is — that illustrates the usefulness of newspapers in family history research. He was looking through newspapers for an obituary about one of his great-uncles. He knew when his great-uncle died but couldn’t find mention of it in the obituary section of the newspaper. As he set the newspaper down (probably in despair), he glanced at the front page — only to find a graphic description of how a local man had been killed in a freak elevator accident. And guess who that local man was? That’s right! He was our friend’s great-uncle. The newspaper not only confirmed for him that his great-uncle lived in that city but also gave our friend a lot more information than he ever expected.

Although newspapers are helpful only if your ancestors did something newsworthy — but you’d be surprised at what was considered newsworthy in the past. Your ancestor didn’t necessarily have to be a politician or a criminal to get his or her picture and story in the paper. Just like today, obituaries, birth and marriage announcements, public records of land transactions, advertisements, and gossip sections were all relatively common in newspapers of the past.

Historical newspapers are now finding their way online. Most of these sites contain just partial collections of newspapers, but they may just have the issue that contains information on your ancestor. The following are some of the larger national collections:

- Chronicling America (

http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov), a free searchable site containing newspapers from 1789 to 1924 - GenealogyBank (

www.genealogybank.com), a subscription site containing over 7,000 newspapers - Google News Newspapers (

http://news.google.com/newspapers), a free collection of newspapers from the United States and Canada - NewspaperArchive.com (

http://newspaperarchive.com), a subscription site with titles from the United States, Canada, Europe, Africa, and Asia. - Newspapers.com (

www.newspapers.com), a subscription site containing digitized copies of over 4,900 newspapers from the United States - Papers Past (

http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz), two million pages of New Zealand newspapers from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries - Trove (

http://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper), a free site from the National Library of Australia that has digitized over 205 million pages of newspapers

There are also some state collections, such as the following:

- Arizona Memory Project,

http://adnp.azlibrary.gov - California Digital Newspaper Collection,

http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc - Historic Oregon Newspapers,

http://oregonnews.uoregon.edu - Library of Virginia,

http://virginiachronicle.com - Missouri Digital Newspaper Project,

http://shsmo.org/newspaper/mdnp - New York Heritage Digital Collections,

https://www.nyheritage.org/newspapers - North Carolina Newspaper Digitization Project,

http://exhibits.archives.ncdcr.gov/newspaper/ - Utah Digital Newspapers,

http://digitalnewspapers.org - Washington Historic Newspapers,

https://www.sos.wa.gov/library/newspapers/newspapers.aspx

There is even a search engine that you can use to find items in digitized newspapers around the world. Elephind.com (www.elephind.com) indexes over 3,000 newspaper titles from Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, and the United States.

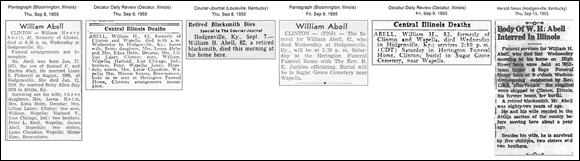

Obituaries can be a key tool for family historians to understand the sequence of events of an ancestor’s life. However, it is important to validate the information contained within the obituary and to search for multiple sources for obituaries, in case one was printed in a newspaper in a town the person formally lived in. A good illustration of this is William Henry Abell.

While William Henry Abell died in Hodgenville, Kentucky in 1955, he was buried in Illinois. And he spent a good deal of time living in Illinois prior to his death. He also had a lot of family members still living in Illinois at the time of his death. To see if there were obituaries and funeral notices in Illinois newspapers, we searched the subscription newspaper archive, Newspapers.com.

-

Go to the Newspapers.com website (

www.newspapers.com).If you don’t have a subscription to the site, you can click on the Try 7 Days Free offer and fill out the appropriate information. If you do have a subscription, you can log in using the Sign-In link on the right side of the menu bar.

-

In the search field, type a name and a year of death and click the Search button.

We typed William Abell and September 1955. The results page had 71 matches. We can narrow down the results by altering the date range on the calendar or by selecting a state from the left column.

-

Select a state from the map to narrow the results.

We were interested in Illinois, so we clicked on that state. The results page showed 15 results.

In our case, there were five results that pertained to William Henry Abell — two from the Pantagraph in Bloomington, Illinois; two from the Decatur Daily Review; and one from the Decatur Herald (duplicate of the Decatur Daily Review entry — one is printed in the morning and one in the afternoon). We also changed the state from Illinois to Kentucky and found an additional obituary in the Louisville, Kentucky. Reading carefully, we saw that each entry said different things and may have been written by different people. As a comparison, we also added an obituary copied from microfilm of the Herald News from Hodgenville, Kentucky. Figure 5-8 shows the differences.

FIGURE 5-8: Six items in five different newspapers for William Henry Abell.

Note that each item contains different information and the Decatur Daily Review item from 9 September 1955 misspelled Hodgensville as Hidgenville. The Pantagraph and Decatur Daily Review also mention that the time of death was 6:30 am. The death certificate states that he died at 7:30 am. Although at first glance it might seem to be a discrepancy between the obituary and death certificate, they do match because Hodgenville is on Eastern time and his death at 7:30 Eastern time would have been 6:30 Central time (the time in Decatur and Bloomington, Illinois). The Herald News item appeared a week later and contained a few more details about where William Henry Abell lived while he was in LaRue County, Kentucky.

Sometimes, instead of a birth certificate, you may find another record in the family’s possession that verifies the existence of the birth record. For example, instead of having a certified copy of a birth certificate, Matthew’s grandmother had a Certificate of Record of Birth. This certificate attests to the fact that the county has a birth record and notes its location. These certificates were used primarily before photocopiers became commonplace, and it became easier to get a certified copy of the original record. If you encounter a Certificate of Record of Birth, be sure to do further research and find the actual birth record. Sometimes the information on the Certificate of Record of Birth was copied incorrectly or there may be further information in the birth record that is not reflected on the Certificate.

Sometimes, instead of a birth certificate, you may find another record in the family’s possession that verifies the existence of the birth record. For example, instead of having a certified copy of a birth certificate, Matthew’s grandmother had a Certificate of Record of Birth. This certificate attests to the fact that the county has a birth record and notes its location. These certificates were used primarily before photocopiers became commonplace, and it became easier to get a certified copy of the original record. If you encounter a Certificate of Record of Birth, be sure to do further research and find the actual birth record. Sometimes the information on the Certificate of Record of Birth was copied incorrectly or there may be further information in the birth record that is not reflected on the Certificate.