Chapter 6

Mapping the Past

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Identifying where your ancestors lived

Identifying where your ancestors lived

![]() Locating places on maps and in history

Locating places on maps and in history

![]() Using maps in your research

Using maps in your research

![]() Getting information from local sources

Getting information from local sources

Say you dig up an old letter addressed to your great-great-great-grandfather in Winchester, Virginia. But where is Winchester? What was the town like? Where exactly did he live in the town? What was life like when he lived there? To answer these questions, you need to go a little further than just retrieving documents — you need to look at the life of your ancestor within the context of where he lived.

Geography played a major role in the lives of our ancestors. It often determined where they lived, worked, and migrated. (Early settlers typically migrated to lands that were similar to their home state or country.) It can also play a major role in how you research your ancestor. Concentrating on where your ancestor lived can point you to area-specific record sets or offer clues about where to research next.

A number of tools and technologies can assist you in meeting your research goals. These tools include geographic information system applications, geocoding, and geographic applications specific to genealogy. In this chapter, we look at several ways to use geographical resources to provide a boost to your family history research, and to answer some outstanding questions we have about William Henry Abell’s family along the way.

For example, we show how we can use geographic-based resources to shed light on why William Henry Abell’s wife, Lizzie (Pickerell) Abell, died young, where it happened, and what he was doing between his wife’s death and his marriage to Betty a decade later.

Are We There Yet? Researching Where “There” Was to Your Ancestors

What did “there” mean for your ancestors? You have to answer this question to know where to look for genealogical information. These days, a family that lives in the same general area for more than two or three generations is rare. If you’re a member of such a family, you may be in luck when it comes to researching. However, if you come from a family that moved around at least every few generations (or a family whose members did not all remain in the same location), you may be in for a challenge.

How do you find out where your ancestors lived? In this section, we look at several resources you can use to establish locations: using known records, interviewing relatives, consulting gazetteers, looking at maps, using GPS devices, and charting locations by using geographical software.

Using documents that you already possess

When you attempt to locate your ancestors geographically, start by using any copies of records or online data that you or someone else has already collected. Read through all those photocopies and original documents from the attic and printouts from online sites — those details can help you determine places to look for additional information about your ancestors. Pay particular attention to any material that provides definite whereabouts during a specific time period. You can use these details as a springboard for your geographical search.

One of William Henry Abell’s obituaries mentions that Lizzie (Pickerell) Abell died on 12 January 1918, but it doesn’t mention where. It appears from the obituary that William Henry Abell was a widower from 1918, until he married Betty Allen in July 1929 in Attilla, Kentucky.

Sifting through the census records that we collected (see Table 4-1 in Chapter 4 for the contents of the Abell census records), we see that William Henry Abell, Lizzie, and four children lived on a rented farm in Tremont Township, Tazewell County, Illinois, in 1910. In 1920, William Henry Abell lived as a wage worker on a farm in Waynesville Township, DeWitt County, Illinois, with his five children. Because the obituary mentioned that Lizzie died in 1918, we could hypothesize that Lizzie died in one of these two counties. Incidentally, Tremont Township is in the central part of Tazewell County and Waynesville Township is in the upper-west corner of De Witt County. The distance between the two principal towns within the townships (Tremont and Waynesville) is about 40 miles. One county lies in between — McLean County.

We can use these details to launch our search through geographic sites to find some insight on the life of William Henry Abell.

Where is Llandrindod, anyway?

At some point during your research, you’re bound to run across something that says an ancestor lived in or was associated with a particular town or county, but your resource contains no details of where that place was — no state or province or other identifiers. How do you find out where that place was located?

A gazetteer, or geographical dictionary, provides information about places. By looking up the name of the town, county, or some other kind of place, you can narrow your search for your ancestor. The gazetteer identifies every place by name and provides varying information (depending on the gazetteer) about each. Typically, gazetteers provide at least the name of the principal region where the place is located. Many contemporary gazetteers available online also provide the latitude and longitude of the place.

By adding the information you get from the online gazetteer to the other pieces of your puzzle, you can reduce the list of places with the same name to just those you think are plausible for your ancestors. By pinpointing the location of a place, you can look for more records to prove whether your ancestors really lived there and even visit the location to get pictures of burial plots or old properties.

For research in the United States, a first stop is the U.S. Geological Survey’s Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) website. The GNIS site contains information on more than two million places within the United States and its territories (the site also includes data for Antarctica).

-

Start your web browser and head to the U.S. Geological Survey’s Geographic Names Information System (GNIS):

http://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublicThis page contains the search form for the United States and its territories, as shown in Figure 6-1.

-

Enter any information that you have, tabbing or clicking to move between fields.

We’re looking for the cemetery in Illinois where we believe William Henry Abell is buried. Remember that we found the name of a cemetery in funeral notice mentioned in the previous section, so we entered Sugar Grove in the Feature Name field and selected Illinois from the state drop-down list. To target your search, you can select a Feature Class to the right of the Feature Name field. In our case, we selected Cemetery as the feature class.

If you’re not sure what a particular field asks for but you think you may want to enter something in it, click the title of the field for an explanation.

If you’re not sure what a particular field asks for but you think you may want to enter something in it, click the title of the field for an explanation. -

When you’re finished, click Send Query.

The search results page appears with nine matches for Sugar Grove Cemetery. Of those results, one Sugar Grove Cemetery is located in De Witt County, Illinois. De Witt County is located between Macon County (where Decatur is located) and McLean County (where Bloomington is located) and Wapella is located in De Witt County (matching the location mentioned in the newspaper articles). The cemetery is located at latitude of 40 degrees, 16 minutes, 5 seconds north and longitude of 88 degrees, 56 minutes, 20 seconds west and is found on the Heyworth map. Next, we can use an online map to plot the longitude and latitude to see the actual location of the cemetery.

FIGURE 6-1: Use the query form to search for places in the United States.

-

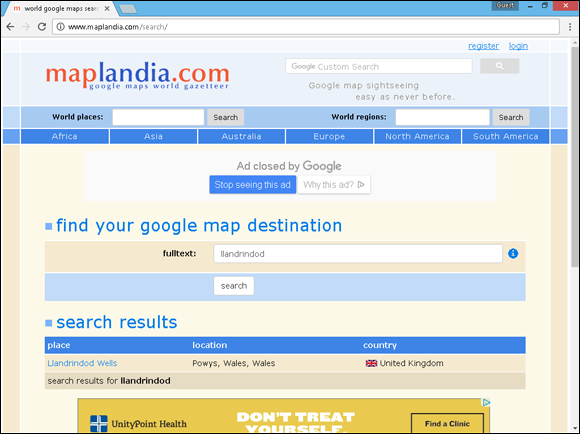

Using your web browser, go to Maplandia.com at

www.maplandia.com.You see the welcome page, which has search fields to look for locations by place-name or region.

-

In the World Places field, type the name of the place you’re trying to locate.

If you’re trying to identify an entire region, you may prefer to use the World Regions field instead.

We entered the Llandrindod place-name.

-

Click Search.

Figure 6-2 shows the results of the search. The only result for our example was a place called Llandrindod Wells in Powys, Wales, in the United Kingdom. Clicking the result takes us to a page that contains the longitude and latitude of Llandrindod Wells and a map of the town.

FIGURE 6-2: Results for a search on Llandrindod at Maplandia.com.

Following are some gazetteer sites for you to check out. You can use some for worldwide searches; others are country specific:

This site has a worldwide focus.

-

Directory of Cities, Towns, and Regions in Belgium

-

Canada’s Geographical Names

-

China Historical GIS

-

Gazetteer of Australia Place Name Search

-

Gazetteer for Scotland

-

Gazetteer of British Place Names

-

GENUKI Gazetteer

www.genuki.org.uk/big/GazetteerThe gazetteer covers England, Ireland, Wales, Scotland, and the Isle of Man.

-

German Historic Gazetteer

-

Institut Géographique National (in French)

-

IreAtlas Townland Data Base (Ireland)

-

Metatopos.org (in Dutch)

-

Land Information New Zealand ( LINZ )

www.linz.govt.nz/regulatory/place-names/find-place-name/new-zealand-gazetteer-place-names -

KNAB, the Place Names Database of EKI (in Estonian and English)

-

Registro Nacional de Informacion Geografica (in Spanish)

-

Kartverk (in Norwegian)

-

Swedish Gazetteer

-

GPS Data Team: Coordinate Finder

Most online gazetteers are organized on a national level and provide information about all the places (towns, cities, counties, landmarks, and so on) within that country. However, you find some exceptions. Some unique gazetteers list information about places within one state or province. One such example is the Kentucky Atlas and Gazetteer (www.kyatlas.com), which has information only about places within — you guessed it — Kentucky.

There’s No Place like Home: Using Local Resources

A time will come (possibly early in your research) when you need information that’s maintained on a local level — like, say, a copy of a record stored in a local courthouse, confirmation that an ancestor is buried in a particular cemetery, or just a photo of the old homestead. How can you find and get what you need?

Finding the needed record is relatively easy if you live in or near the county where the information is maintained — you decide what you need, find out where it’s stored, and then go get a copy. Getting locally held information isn’t quite as easy, however, if you live in another county, state, or country. Although you can determine what information you need and where it may be stored, finding out whether the information is truly kept where you think it is and then getting a copy is another thing. Of course, if this situation weren’t such a common occurrence for genealogists, you could just make a vacation out of it — travel to the location to finish researching there and get the copy you need while sightseeing along the way. But unfortunately, needing records from distant places is a common occurrence, and most of us can’t afford to pack our bags and hit the road every time we need a record or item from a faraway place — which is why it’s nice to know that resources are available to help.

A lot of resources are available to help you locate local documents and obtain copies, such as these:

- Geographic-specific websites

- Local genealogical and historical societies

- Libraries with research services

- Individuals who are willing to do lookups in public records

- Directories and newspapers

- Localizing searches

Some resources are free, but others may charge you a fee for their time, and still others will bill you only for copying or other direct costs.

Geographic-specific websites

Geographic-specific websites are pages that contain information only about a particular town, county, state, country, or other locality. They typically provide information about local resources, such as genealogical and historical societies, government agencies and courthouses, cemeteries, and civic organizations. Some sites have local histories and biographies of prominent residents online. Often they list and have links to other web pages with resources for the area. Sometimes they even have a place where you can post queries (or questions) about the area or families from there in the hope that someone who reads your query will have some answers for you.

You can find several good examples of general geographic-specific websites:

- The USGenWeb Project (

www.usgenweb.org) conveys information about the United States. The USGenWeb Project is an all-volunteer, online effort to provide a central genealogical resource for information (records and reference materials) pertaining to counties within each state. - GENUKI: UK + Ireland Genealogy (

www.genuki.org.uk) is an online reference site that contains primary historical and genealogical information in the United Kingdom and Ireland. It links to sites containing indexes, transcriptions, or digitized images of actual records. All the information is categorized by locality — by country, then county, then parish. - National Library of Australia (

www.nla.gov.au/research-guides/family-history/other-australasian-resources) has a listing of all sorts of state and territory resources in Australia, including archives, libraries, societies, and cemeteries. It also has links directly to indexes and records at some local levels. - WhatWasThere (

www.whatwasthere.com) is a site that ties historical photographs to Google Maps so that you can see how a specific location appeared in the past. - The WorldGenWeb Project (

www.worldgenweb.org) attempts the same type of undertaking as USGenWeb, only on a global scale.

We typed in the search term Illinois death records in Google (for more on searching Google, see Chapter 7). The first result (that wasn’t a paid advertisement) was for the Illinois Death Certificates, 1916–1950 Index, hosted by the Illinois Secretary of State (https://www.cyberdriveillinois.com/departments/archives/databases/idphdeathindex.html). As Lizzie died in 1918, she should be covered by the database. We searched the database in the following manner:

-

Point your web browser to

https://www.cyberdriveillinois.com/departments/archives/databases/idphdeathindex.html.The Illinois Death Certificates, 1916–1950 web page appears.

-

Click the Search button.

The search page appears.

-

Enter the appropriate search criteria and click Submit.

We entered Abell in the Last Name of Decedent, Lizzie in First Name of Decedent, and chose STATEWIDE in the Select County box.

Figure 6-3 shows that Lizzie Abell died on 12 January 1919 in Funks Grove Township, McLean County, Illinois.

FIGURE 6-3: Index information for Lizzie Abell.

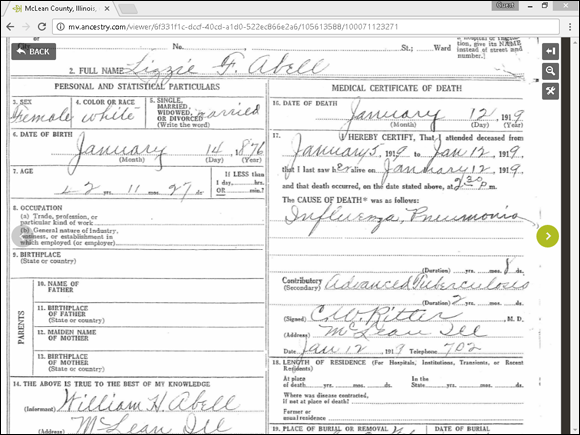

Now we had an inconsistency to resolve. The obituary said she died on 12 January 1918 and the index says she died on 12 January 1919. Only the death certificate (the primary source) could resolve it. Unfortunately, death certificates for the state of Illinois are not online. We had to get the certificate from another source.

Libraries and archives

Often, the holdings in local libraries and archives can be of great value to you — even if you can’t physically visit the library or archive to do your research. You can simply go online to determine whether that repository has the book or document you need. (Most libraries and archives have web pages with their card catalogs or another listing of their holdings.) After seeing whether the repository has what you need, you can contact it to borrow the book or document (if it participates in an interlibrary loan program) or to get a copy of what you need. (Most libraries and archives have services to copy information for people at a minimal cost.)

Figure 6-4, shows the copy of the death certificate from the county clerk. Lizzie F. Abell died of influenza and pneumonia after being sick for eight days on 12 January 1919. Contributing to her demise was advanced tuberculosis, which she suffered with for two years.

FIGURE 6-4: Lizzie Abell’s (Pickerell) death certificate.

From the record, we learned two things — the obituary for William Henry Abell (see Chapter 5 for more on the obituaries) was incorrect about her death date and she was a victim of the Spanish flu pandemic that affected thousands of Americans in 1918 and early 1919.

Pulling the obituary

While the death certificate has some facts, we wanted more context to the Abell family’s life. A good source for that context can often be an obituary. Newspapers can be a treasure trove of geographic-specific information. Not only do they contain obituaries, but they contain news articles that you can use to develop a picture of the world in which your ancestors lived.

After we determined the actual death date, we searched for an obituary for Lizzie Pickerell at Newspapers.com. We used the search terms lizzie abell Illinois 1919 in the Newspapers.com search mechanism and received two results. The first result was Lizzie’s obituary in the Bloomington, Illinois, Pantagraph (see Figure 6-5).

FIGURE 6-5: Lizzie Abell’s (Pickerell) obituary at Newspapers.com.

The obituary contained nice details to help us fill in some gaps. The Abells had moved to Wapella, Illinois, in October 1898, about a month after William Henry Abell married Lizzie Pickerell. In March 1918, they moved to the Lee Longworth farm, three miles east of the town of McLean (where Lizzie died). With the details of the obituary, we can look for resources to approximate where they lived on a map.

Genealogical and historical societies

Most genealogical and historical societies exist on a local level and attempt to preserve documents and history for the area in which they are located. Genealogical societies also have another purpose — to help their members research their ancestors whether they lived in the local area or elsewhere. (Granted, some surname-based genealogical societies, and even a few virtual societies, are exceptions because they aren’t specific to one place.) Although historical societies usually don’t have a stated purpose of aiding their members in genealogical research, they are helpful to genealogists anyway. Often, if you don’t live in the area from which you need a record or information, you can contact a local genealogical or historical society to get help. Help varies from lookup services in books and documents the society maintains in its library to volunteers who locate and obtain copies of records for you. Before you contact a local genealogical or historical society for help, be sure you know the services it offers.

Many local genealogical and historical societies have web pages that identify exactly which services they offer to members and nonmembers online. To find a society in an area you’re researching, try a search in a search engine, such as the following:

McLean County Illinois society genealogy OR historical

Or, you can find an index of genealogical and historical societies — such as the FamilySearch United States Societies page (https://familysearch.org/wiki/en/United_States_Societies) or the Federation of Genealogical Societies directory (www.fgs.org/cstm_societyHall.php).

In our case, we were able to locate the McLean County Museum of History, which houses an archive and the library for the local genealogical society. A directory in that library provided our next piece of valuable information.

Looking at local directories

If you have a general idea of where your family lived at a particular time but no conclusive proof or if you just want to fill in the gaps between censuses, city and county directories may help. Directories can help you confirm whether your ancestors indeed lived in an area and, in some cases, they can provide even more information than you expect.

Like today’s telephone books, the directories of yesteryear contained basic information about people who lived in a geographic location, whether the areas were towns, cities, districts, or counties. At a minimum, the directory identified the head of the household and the location of the house. Some directories also included the names and ages of everyone in the household and occupations of any members of the household who were employed.

When looking for a city directory, you can consult a subscription genealogy site, such as Ancestry.com, or look for other sources at the City Directories of the United States of America at www.uscitydirectories.com. The intent of this site is to identify repositories of city directories online and offline and to guide you to them.

Other sites can lead you to directories for particular geographic areas too. Don’s List contains links to directories of a number of states at www.donslist.net/PGHLookups/Dir1Win.shtml. You can find a list of city directories available on microfilm at the Library of Congress for nearly 700 American towns and states through the U.S. City Directories on Microfilm in the Microform Reading Room web page (www.loc.gov/rr/microform/uscity). If you’re looking for city directories for England and Wales, look at the Historical Directories site (http://cdm16445.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/p16445coll4). The site contains digitized directories from 1760s to 1910s. You can also often find lists of city directories on the websites of local and state libraries.

Some individuals have posted city directories in their areas. An example of this is the Fredericksburg, Virginia, City Directory 1938 page at http://resources.umwhisp.org/Fredericksburg/1938directory.htm.

For some digitized city directories consult the Internet Archive site at www.archive.org and type “city directories” in the search field for a list of available directories.

Because William Henry Abell was a tenant farmer (meaning he rented the land rather than owning it), it is sometimes difficult to find records showing where he lived (outside of a census year). In this case, we needed to find where he lived in 1918–1919. Because we knew from the death certificate and Lizzie’s obituary that they were living in McLean County, we took a trip to the McLean County Museum of History to see if there were resources that could help.

In the museum’s library, we found a directory of all farmers for McLean County dated 1917. Not the exact year we needed, but close enough. Lizzie’s death certificate said that she died in Funks Grove Township and her obituary mentioned that the Abells lived three miles east of the town of McLean on the Lee Longworth farm. We needed to find an entry in Funks Grove Township for Lee Longworth. Sure enough, in the directory there was an entry for Lester Lee Longworth (with his wife Blanche and son Lyle) who lived on a farm along McLean Route 2. They were tenant farmers on 400 acres belonging to the Wheeler Brothers, located in Section 8 and 9 South in Funks Grove Township. Figure 6-6 shows the entry in the directory found online at the Hathi Trust website (www.hathitrust.org).

FIGURE 6-6: Farmer’s Review Farm Directory at the Hathi Trust site.

Professional researchers

If we had not been able to find additional information at the McLean County Museum of History ourselves, we might have enlisted the help of others — one option would have been to engage a professional researcher. Professional researchers are people who research your genealogy — or certain family lines — for a fee. If you’re looking for someone to do all the research necessary to put together a complete family history, some do so. If you’re just looking for records in a specific area to substantiate claims in your genealogy, professional researchers can usually locate the records for you and get you copies. Their services, rates, experience, and reputations vary, so be careful when selecting a professional researcher to help you. Look for someone who has quite a bit of experience in the area in which you need help. Asking for references or a list of satisfied customers isn’t out of the question. (That way, you know who you’re dealing with before you send the researcher money.) To find a researcher in a particular location, you can do a search by geographic specialty on the Association of Professional Genealogists website at www.apgen.org/directory/search.html?type=geo_specialty&new_search=true.

For an introduction on hiring a professional researcher see the FamilySearch Wiki entry at https://familysearch.org/wiki/en/Hiring_a_Professional_Researcher. Another place to look for help is the genealogyDOTcoach site at https://genealogy.coach. If you just need a boost to your research, you can pay for small amounts of time of a researcher from this website.

Localizing your search

To find a lot of detail about a specific area and what it was like during a specific timeframe, local histories are the answer. Local histories often contain information about when and how a place was settled and may have biographical information on earlier settlers or the principal people within the community who sponsored the creation of the history.

Online local histories can be tucked away in geographically specific websites, historical society pages, library sites, and web-based bookstores. You can also find a few sites that feature local histories:

- Ancestry.com (

www.ancestry.com) features several thousand works in its Stories, Memories, and Histories collection. - A collection of Canadian local histories is available at Our Roots/Nos Racines (

www.ourroots.ca). - You can search by location and find a growing collection of local histories on Google Books (

http://books.google.com). - FamilySearch Family History Books collection (

https://books.familysearch.org) contains over 325,000 genealogy and family history publications including local histories digitized from 12 libraries. - The Internet Archive (

http://archive.org) contains digitized versions of thousands of local histories. (See Figure 6-7.) - The digital library at Hathi Trust (

www.hathitrust.org) contains a vast collection of local histories.

FIGURE 6-7: A local history at the Internet Archive.

To get more details on what was going on in McLean County during the early twentieth century, we read the History of McLean County Illinois published in 1924. The book covered items such as local agriculture (William Henry Abell was a farmer), industrial development, churches, and schools within the county.

Gaining historical perspective

We’ve mentioned a few times that family history isn’t just about names and dates but also about gaining an appreciation of the historical context your ancestors lived within — the things going on in the country or locality they lived in — and how that context might have affected the choices in their lives. One site that attempts to help you sort that out is HistoryLines at https://historylines.com. HistoryLines helps you create a sketch of your ancestor’s life based upon the time and location that they lived within. Try the following:

-

Point your web browser to

https://historylines.com.The HistoryLines web page appears.

- Click the Get Started button and complete the sign up process.

-

Enter information on the form about an ancestor.

We entered Lizzie F. in the first name field; Pickerell in last name; 14 January 1876 in birth date; LaRue, Kentucky, United States in birth place (the field may automatically populate a location while you type); 12 January 1919 in death date; Funks Grove, McLean, Illinois, United States in death place; and selected the Female checkbox. You can also opt to import a GEDCOM file or import from a FamilySearch account.

-

Click the Start a Story button.

The historical sketch appears as seen in Figure 6-8.

FIGURE 6-8: Historical sketch produced at HistoryLines.

You can further personalize the sketch by entering your own text and adding photographs.

If we had not discovered the death certificate already, the sketch that we produced may have provided a clue as to what happened to Lizzie. Near the bottom of the sketch it mentions that the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 had a profound effect on the population — killing more than 650,000 Americans.

Mapping Your Ancestor’s Way

After you determine where a place is located, it’s time to dig out the maps. Maps can be an invaluable resource in your genealogical research. Not only do maps help you track your ancestors’ locations at various points in their lives, but they also enhance your published genealogy by illustrating some of your findings.

Different types of online sites have maps that may be useful in your genealogical research.

-

Historical maps: Several websites contain scanned or digitized images of historic maps. In a lot of cases, you can download or print copies of these maps. Such sites include the following:

- David Rumsey Map Collection:

www.davidrumsey.com - Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin:

www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/index.html - Map Collections of the Library of Congress:

www.loc.gov/maps/collections/

You can also find local collections of maps at several university and historical society sites. Here are a few examples:

- Cartography: Historical Maps of New Jersey (Rutgers University):

http://mapmaker.rutgers.edu/MAPS.html - Historical Maps Online (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign):

http://imagesearchnew.library.illinois.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/maps - Massachusetts Maps (The Massachusetts Historical Society):

www.masshist.org/online/massmaps

- David Rumsey Map Collection:

- Digitized historical atlases: In addition to map sites, individuals have scanned portions or the entire contents of atlases, particularly those from the nineteenth century. Examples include the following:

- Countrywide atlases: Atlas of Historical County Boundaries at

http://publications.newberry.org/ahcbp/. - County atlases: The 1904 Maps from the New Century Atlas of Cayuga County, New York

www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~nycayuga/maps/1904/and Historic Map Works atwww.historicmapworks.com. - Specialty atlases: An occupational example is the 1948 U.S. Railroad Atlas at

http://trains.rockycrater.org/pfmsig/atlas.php.

- Countrywide atlases: Atlas of Historical County Boundaries at

-

Interactive map sites: A few sites have interactive maps that you can use to find and zoom in on areas. When you have the view you want of the location, you can print a copy of the map to keep with your genealogical records. Here are some examples:

- Google Maps:

https://www.google.com/maps/ - MapQuest:

https://www.mapquest.com/ - Bing Maps:

https://www.bing.com/maps - National Geographic MapMachine:

http://maps.nationalgeographic.com/maps - The U.K. Street Map Page:

www.streetmap.co.uk

Interactive maps are especially helpful when you’re trying to pinpoint the location of a cemetery or town you plan to visit for your genealogical research, but they’re limited in their historical helpfulness because they typically offer only current information about places.

- Google Maps:

Fortunately, there was a plat map made in 1914. The McLean County Museum of history had a copy and it is found on line at the Library of Congress Map site. We found it by putting 1914 McLean County Illinois plat map into the Google search field, which returned the Library of Congress Map site results at https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4103mm.gct00184/?sp=34. We looked toward the bottom of the plat map of Funks Grove Township (as the Sections were 8 and 9 South) and found the two sections. As seen in Figure 6-9, at the very southern edge of the township sections, on the De Witt county border, was a tract of 400 acres belonging to M.C. W. Wheeler (aka, the Wheeler Brothers).

FIGURE 6-9: A 1914 plat map from the Library of Congress website.

Zeroing in

We’ve looked at a few types of maps, but the real promise of mapping technology is the ability to use different maps together to see the whole picture of where your ancestors lived. One of the ways of doing this is by using mapping layers.

Some government agencies and private firms make geographic information systems (GIS) data available on their websites. This data often has a base map and then a variety of layers showing different information that can be placed on top of it. If you want to make your own maps and layers, a good example of mapping layers is the Google Earth technology. Google Earth (www.google.com/earth/index.html) is a downloadable program that combines Google searches with geographic information. Enter a place-name or a longitude and latitude coordinate, and the system maps it for you. Then you can add more map layers to see other information about that particular place.

Several websites make layers that are specifically made to work with Google Earth. For example, you can download historical county boundary data for use on Google Earth (through KMZ files) from the Atlas of Historical County Boundaries maintained by the Newberry Library (http://publications.newberry.org/ahcbp/downloads/united_states.html). With these files you can see what current geographic features might have been in a county in the past.

-

Point your web browser to the McLean County Regional Planning Commission page at

http://mcgis.org/department/?structureid=3.The Online Mapping page appears.

-

In the left column, click on the Historic link.

The link is located under the In This Section menu about two-thirds of the way down the list of links. The McGIS application appears with a default map. In our case, the default map was from 1856 — too early for our search.

-

Click the I Want To button in the top-left corner of the page.

A drop-down menu appears.

-

Select Change Visible Map Layers from the menu.

A set of layers appears in the left column.

-

In the left column, deselect the Historic_1856 layer and select the Imagery_2014 layer.

A satellite map of McLean County from 2014 appears. We’ll use this as our base layer because it is the most current map and because it shows us things as they appear today (well, close enough, anyway).

-

Click the Historic_1914 layer in the left column.

The familiar plat map of 1914 is overlaid on top of the 2014 satellite map.

-

Click on the Plus button near the I Want To button to zoom in on the map.

We zoomed into the map and then clicked on the map to pull the map up until we saw the bottom of Funks Grove Township.

-

Locate the appropriate sections and then move the slider to make the historic layer more transparent.

The slider is located to the right of the Historic_1914 label. Dragging the slider to the left lightens the layer. You should be able to see detail of the satellite map with the outline of the plat map.

-

Click the Transportation layer in the left column to see current roads.

With the transportation layer on (in Figure 6-10), we can see which roads to take to get to the actual property.

FIGURE 6-10: Layered map of William Henry Abell’s residence in 1919.

Although interactive maps are good for getting a general idea of the location of a place, more specific maps are sometimes necessary for feature types such as creeks or ridges. Topographic maps are an especially good set to use for these purposes; they contain not only place-names but also information on features of the terrain (such as watercourses, elevation, vegetation density, and, yes, even cemeteries). At the National Geographic site, you can view a variety of maps, including topographical maps.

To view a topographic map at the National Geographic, follow these steps:

-

Direct your browser to

http://www.natgeomaps.com/trail-maps/pdf-quads.A map of the United States appears near the bottom of the page.

-

In the search box near the middle of the page (on the map of the United States) set the drop-down box to pdf_topo and type in the map name.

We typed Funks Grove and clicked the Search button. The map zooms into the selected area and a map thumbnail appears.

-

Click the map thumbnail to see the map.

A topographic map appears for McLean, Illinois. There are four areas marked on the map that we can zoom into.

-

We chose to zoom into section 4 and clicked on the small circle with the number 4 in it.

The topographic map appears on the screen. We zoomed into the map to get a better look at the terrain, as shown in Figure 6-11.

FIGURE 6-11: A topographical map of the land where William Henry Abell lived.

Crossing the line

Just as maps help you track your ancestors’ movements and where they lived, they can also help you track when your ancestors didn’t really move. Boundaries for towns, districts, and even states have changed over time. Additionally, towns and counties sometimes change names. Knowing whether your ancestors really moved or just appeared to move because a boundary or town name changed is important when you try to locate records for them.

To determine whether a town or county changed names at some point, check a gazetteer or historical text on the area. (Gazetteers are discussed earlier in this chapter, in the “Where is Llandrindod, anyway?” section.) Finding boundary changes can be a little more challenging, but resources are available to help you. For example, historical atlases illustrate land and boundary changes. You can also use online sites that have maps for the same areas over time, and a few sites deal specifically with boundary changes in particular locations. Here are a few examples:

- Atlas of Historical County Boundaries:

http://publications.newberry.org/ahcbp - The Counties of England, Wales, and Scotland Prior to the 1974 Boundary Changes:

www.genuki.org.uk/big/Britain.html

You can also use software designed to show boundary changes over time. Programs like these can help you find places that have disappeared altogether:

- The Centennial Historical Atlas tracks boundary changes in Europe and the Middle East. Its website is

www.clockwk.com. - AniMap Plus tracks boundary changes in the United States. Its website is

www.goldbug.com/AniMap.html.

The following is a quick walkthrough using the Atlas of Historical County Boundaries to see how some counties have changed over time:

-

Point your web browser to

http://publications.newberry.org/ahcbp.The homepage for the atlas appears. You can choose to look at data at a national level or the county level. Continuing with the earlier example, we are interested in finding more information about De Witt County, Illinois.

-

Click the state that interests you.

We clicked on Illinois. A page appears with links to view an interactive map, an index of counties, a chronology of state and county boundaries, individual county chronologies, a bibliography, historical commentary, and downloadable geographic information system (GIS) files.

-

Click the View Interactive Map heading.

A map of the state appears. You can use the toolbar on the left side of the screen to zoom in or out of the map, measure distances, create a query, and print the map.

-

Under Select Map Date (in the upper-right corner of the screen), type in the date that interests you.

We typed in Feb 26 1845.

-

Click the Refresh Map button.

The county boundaries change based upon the date that you entered.

-

Use the Zoom In button on the toolbar to see the county boundaries more clearly.

The county boundaries change based upon the date that you entered.

Also, there are a few online resources that can display the movements of your ancestors based upon the contents of your genealogy application or FamilySearch Online Tree, such as Ancestral Atlas (www.ancestralatlas.com) and RootsMapper (https://rootsmapper.com).

Positioning your family: Using global positioning systems

After discovering the location of the final resting place of great-great-great-grandpa, you just might get the notion to travel to the cemetery. Now, finding the cemetery on the map is one thing, but often finding the cemetery on the ground is a completely different thing. That is where global positioning systems come into play.

A Global Positioning System (GPS) is a device that uses satellites to determine the exact location of the user. The technology is sophisticated, but in simple terms, satellites send out radio signals that are collected by the GPS receiver — the device that you use to determine your location. The receiver then calculates the distances between the satellites and the receiver to determine your location. Receivers can come in many forms, ranging from vehicle-mounted receivers to those that fit inside of your smartphone.

While on research trips, we use GPS receivers not only to locate a particular place but also to document the location of a specific object within that place. For example, when we visit a cemetery, we take GPS readings of the gravesites of ancestors and then enter those readings into our genealogical databases. That way, if the marker is ever destroyed, we still have a way to locate the grave. As a final step, we take that information and plot the specific location of the sites on a map, using geographical information systems software. (See the following section for more details on geographical information systems.)

There are several smartphone apps that you can use for GPS readings. For example, although not made specifically for genealogy, the iPhone app MotionX-GPS (gps.motionx.com) contains a variety of tools that are useful for the genealogist in the field. It can show your position on the street, topographic maps, and satellite maps. You can also set the application to track your movements and set waypoints as you go. The application even has a built-in compass and the capability to take a picture and automatically associate it with a latitude and longitude.

Plotting against the family

Although finding the location where your ancestors lived on a map is interesting, it’s even more exciting to create maps specific to your family history. One way genealogists produce their own maps is by plotting land records: They take the legal description of the land from a record and place it into land-plotting software, which then creates a map showing the land boundaries. A couple of programs for plotting boundaries are DeedMapper, by Direct Line Software (www.directlinesoftware.com/deedmapper_42), and Metes and Bounds, by Sandy Knoll Software (www.tabberer.com/sandyknoll/more/metesandbounds/metes.html). For an online way to plot a boundary, see Plat Plotter at http://platplotter.appspot.com. And a subscription site called HistoryGeo.com has lands already plotted and searchable for original landowners of public states. For more information on HistoryGeo.com, refer to Chapter 5. You can also find a number of commercial plotting programs by using a search engine such as Google (www.google.com).

Another way to create custom maps is through geographical information systems (GIS) software. GIS software allows you to create maps based on layers of information. For example, you may start with a map that is just an outline of a county. Then you might add a second layer that shows the township sections of the county as they were originally platted. A third layer might show the location of your ancestor’s homestead based on the legal description of a land record. A fourth layer might show watercourses or other terrain features within the area. The resulting map can give you a great appreciation of the environment in which your ancestor lived.

To begin using GIS resources, you first must acquire a GIS data viewer. This software comes in many forms, including free software and commercial packages. One popular piece of free software is ArcReader, which is available on the ESRI site at www.esri.com/software/arcgis/arcreader/download.html. Then you download (or create) geographical data to use with the viewer. A number of sites contain data, both free and commercial. Starting points for finding data include ArcGIS Online (www.arcgis.com/home), GIS Data Depot (http://data.geocomm.com), and the geospatial portion of Data.gov (http://catalog.data.gov/dataset?metadata_type=geospatial). For an example of using GIS in genealogy, see the article GIS and Genealogy at esri (www.esri.com/esri-news/arcuser/spring-2014/gis-and-genealogy).

You can also use maps from other sources and integrate them into a GIS map. When visiting cemeteries, we like to use GIS resources to generate an aerial photograph of the cemetery and plot the location of the grave markers on it. When we get back home, we use the aerial photograph as the base template and then overlay the grave locations on it electronically to show their exact positions.

For example, when grave hunting for the Sugar Grove Cemetery (discussed earlier in the chapter), we generated an aerial view of the area at Bing.com (www.bing.com/maps). In the search field, we entered the place-name (Bucks Road, Wapella, Illinois) and then clicked on the search icon. When the map appeared, we clicked on the drop-down in the upper-right corner and changed the view from road to Aerial.

Figure 6-12 shows the photograph at its maximum zoom. The cemetery is just to the left of the circle with the address under it. (It’s bordered on the north by Bucks Road and on the west by a plowed field.) This view of the cemetery helps a lot when we try to find it on the ground.

FIGURE 6-12: An aerial map at Bing.com.

From the map, we know that the cemetery is right off the road, among farms, and a house sits directly across from it (although we have to keep in mind that the aerial photograph may have been taken long ago — some things might have changed since then).

After plotting the gravestone locations based on GPS readings at the cemetery, we can store that picture in our genealogical database so that it’s easy to find gravestones at that cemetery should we (or anyone else) want to visit it in the future.

Wrapping It Up (with a Surprise)

Just to cover all our bases, we decided to do a search on marriages just to be sure there were no surprises about William Henry Abell. We typed Kentucky marriage index into Google and the first result was the Kentucky Marriages, 1785–1979 index at FamilySearch.org. A search of the database yielded one result — the marriage to Lizzie F. Pickerell. Interestingly, the marriage to Betty mentioned in the obituary as occurring in Kentucky in 1929 did not show in the results.

We checked the Illinois, County Marriages, 1810–1940 index at FamilySearch.org to see if the marriage to Betty occurred in Illinois. The search didn’t show a marriage to Betty — however, a surprise was lurking. The first result was a marriage of William Henry Abell to Cora Shehan Young in De Witt County, Illinois on 11 February 1922. The father of William Henry Abell was listed as Samuel Abell and mother as Martha S. Beard. Both parents were correct from our sources on William Henry Abell. We ordered the marriage license and marriage record from the Illinois Regional Archives and behold William Henry Abell was married to Cora during the period between Lizzie’s death and the marriage to Betty — a fact not mentioned by the family in his obituary (see Figure 6-13).

FIGURE 6-13: William Henry Abell and Cora Young’s marriage license.

For example, Matthew’s great-grandfather, William Henry Abell, is buried in Sugar Grove Cemetery near Wapella, according to funeral announcements in two local newspapers (for more on these newspaper items, refer to

For example, Matthew’s great-grandfather, William Henry Abell, is buried in Sugar Grove Cemetery near Wapella, according to funeral announcements in two local newspapers (for more on these newspaper items, refer to