Chapter 5. Maintaining the Test-Driven Cycle

Every day you may make progress. Every step may be fruitful. Yet there will stretch out before you an ever-lengthening, ever-ascending, ever-improving path. You know you will never get to the end of the journey. But this, so far from discouraging, only adds to the joy and glory of the climb.

—Winston Churchill

Introduction

Once we’ve kick-started the TDD process, we need to keep it running smoothly. In this chapter we’ll show how a TDD process runs once started. The rest of the book explores in some detail how we ensure it runs smoothly—how we write tests as we build the system, how we use tests to get early feedback on internal and external quality issues, and how we ensure that the tests continue to support change and do not become an obstacle to further development.

Start Each Feature with an Acceptance Test

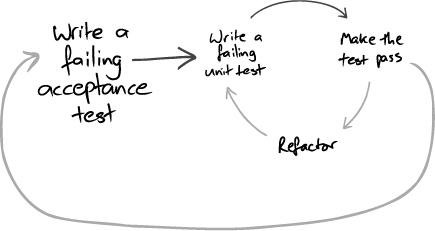

As we described in Chapter 1, we start work on a new feature by writing failing acceptance tests that demonstrate that the system does not yet have the feature we’re about to write and track our progress towards completion of the feature (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Each TDD cycle starts with a failing acceptance test

We write the acceptance test using only terminology from the application’s domain, not from the underlying technologies (such as databases or web servers). This helps us understand what the system should do, without tying us to any of our initial assumptions about the implementation or complicating the test with technological details. This also shields our acceptance test suite from changes to the system’s technical infrastructure. For example, if a third-party organization changes the protocol used by their services from FTP and binary files to web services and XML, we should not have to rework the tests for the system’s application logic.

We find that writing such a test before coding makes us clarify what we want to achieve. The precision of expressing requirements in a form that can be automatically checked helps us uncover implicit assumptions. The failing tests keep us focused on implementing the limited set of features they describe, improving our chances of delivering them. More subtly, starting with tests makes us look at the system from the users’ point of view, understanding what they need it to do rather than speculating about features from the implementers’ point of view.

Unit tests, on the other hand, exercise objects, or small clusters of objects, in isolation. They’re important to help us design classes and give us confidence that they work, but they don’t say anything about whether they work together with the rest of the system. Acceptance tests both test the integration of unit-tested objects and push the project forwards.

Separate Tests That Measure Progress from Those That Catch Regressions

When we write acceptance tests to describe a new feature, we expect them to fail until that feature has been implemented; new acceptance tests describe work yet to be done. The activity of turning acceptance tests from red to green gives the team a measure of the progress it’s making. A regular cycle of passing acceptance tests is the engine that drives the nested project feedback loops we described in “Feedback Is the Fundamental Tool” (page 4). Once passing, the acceptance tests now represent completed features and should not fail again. A failure means that there’s been a regression, that we’ve broken our existing code.

We organize our test suites to reflect the different roles that the tests fulfill. Unit and integration tests support the development team, should run quickly, and should always pass. Acceptance tests for completed features catch regressions and should always pass, although they might take longer to run. New acceptance tests represent work in progress and will not pass until a feature is ready.

If requirements change, we must move any affected acceptance tests out of the regression suite back into the in-progress suite, edit them to reflect the new requirements, and change the system to make them pass again.

Start Testing with the Simplest Success Case

Where do we start when we have to write a new class or feature? It’s tempting to start with degenerate or failure cases because they’re often easier. That’s a common interpretation of the XP maxim to do “the simplest thing that could possibly work” [Beck02], but simple should not be interpreted as simplistic. Degenerate cases don’t add much to the value of the system and, more importantly, don’t give us enough feedback about the validity of our ideas. Incidentally, we also find that focusing on the failure cases at the beginning of a feature is bad for morale—if we only work on error handling it feels like we’re not achieving anything.

We prefer to start by testing the simplest success case. Once that’s working, we’ll have a better idea of the real structure of the solution and can prioritize between handling any possible failures we noticed along the way and further success cases. Of course, a feature isn’t complete until it’s robust. This isn’t an excuse not to bother with failure handling—but we can choose when we want to implement first.

We find it useful to keep a notepad or index cards by the keyboard to jot down failure cases, refactorings, and other technical tasks that need to be addressed. This allows us to stay focused on the task at hand without dropping detail. The feature is finished only when we’ve crossed off everything on the list—either we’ve done each task or decided that we don’t need to.

Write the Test That You’d Want to Read

We want each test to be as clear as possible an expression of the behavior to be performed by the system or object. While writing the test, we ignore the fact that the test won’t run, or even compile, and just concentrate on its text; we act as if the supporting code to let us run the test already exists.

When the test reads well, we then build up the infrastructure to support the test. We know we’ve implemented enough of the supporting code when the test fails in the way we’d expect, with a clear error message describing what needs to be done. Only then do we start writing the code to make the test pass. We look further at making tests readable in Chapter 21.

Watch the Test Fail

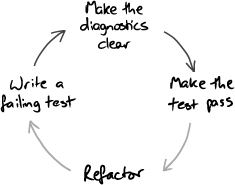

We always watch the test fail before writing the code to make it pass, and check the diagnostic message. If the test fails in a way we didn’t expect, we know we’ve misunderstood something or the code is incomplete, so we fix that. When we get the “right” failure, we check that the diagnostics are helpful. If the failure description isn’t clear, someone (probably us) will have to struggle when the code breaks in a few weeks’ time. We adjust the test code and rerun the tests until the error messages guide us to the problem with the code (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2 Improving the diagnostics as part of the TDD cycle

As we write the production code, we keep running the test to see our progress and to check the error diagnostics as the system is built up behind the test. Where necessary, we extend or modify the support code to ensure the error messages are always clear and relevant.

There’s more than one reason for insisting on checking the error messages. First, it checks our assumptions about the code we’re working on—sometimes we’re wrong. Second, more subtly, we find that our emphasis on (or, perhaps, mania for) expressing our intentions is fundamental for developing reliable, maintainable systems—and for us that includes tests and failure messages. Taking the trouble to generate a useful diagnostic helps us clarify what the test, and therefore the code, is supposed to do. We look at error diagnostics and how to improve them in Chapter 23.

Develop from the Inputs to the Outputs

We start developing a feature by considering the events coming into the system that will trigger the new behavior. The end-to-end tests for the feature will simulate these events arriving. At the boundaries of our system, we will need to write one or more objects to handle these events. As we do so, we discover that these objects need supporting services from the rest of the system to perform their responsibilities. We write more objects to implement these services, and discover what services these new objects need in turn.

In this way, we work our way through the system: from the objects that receive external events, through the intermediate layers, to the central domain model, and then on to other boundary objects that generate an externally visible response. That might mean accepting some text and a mouse click and looking for a record in a database, or receiving a message in a queue and looking for a file on a server.

It’s tempting to start by unit-testing new domain model objects and then trying to hook them into the rest of the application. It seems easier at the start—we feel we’re making rapid progress working on the domain model when we don’t have to make it fit into anything—but we’re more likely to get bitten by integration problems later. We’ll have wasted time building unnecessary or incorrect functionality, because we weren’t receiving the right kind of feedback when we were working on it.

Unit-Test Behavior, Not Methods

We’ve learned the hard way that just writing lots of tests, even when it produces high test coverage, does not guarantee a codebase that’s easy to work with. Many developers who adopt TDD find their early tests hard to understand when they revisit them later, and one common mistake is thinking about testing methods. A test called testBidAccepted() tells us what it does, but not what it’s for.

We do better when we focus on the features that the object under test should provide, each of which may require collaboration with its neighbors and calling more than one of its methods. We need to know how to use the class to achieve a goal, not how to exercise all the paths through its code.

It helps to choose test names that describe how the object behaves in the scenario being tested. We look at this in more detail in “Test Names Describe Features” (page 248).

Listen to the Tests

When writing unit and integration tests, we stay alert for areas of the code that are difficult to test. When we find a feature that’s difficult to test, we don’t just ask ourselves how to test it, but also why is it difficult to test.

Our experience is that, when code is difficult to test, the most likely cause is that our design needs improving. The same structure that makes the code difficult to test now will make it difficult to change in the future. By the time that future comes around, a change will be more difficult still because we’ll have forgotten what we were thinking when we wrote the code. For a successful system, it might even be a completely different team that will have to live with the consequences of our decisions.

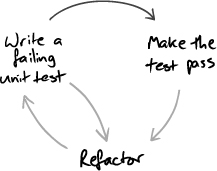

Our response is to regard the process of writing tests as a valuable early warning of potential maintenance problems and to use those hints to fix a problem while it’s still fresh. As Figure 5.3 shows, if we’re finding it hard to write the next failing test, we look again at the design of the production code and often refactor it before moving on.

Figure 5.3 Difficulties writing tests may suggest a need to fix production code

This is an example of how our maxim—“Expect Unexpected Changes”—guides development. If we keep up the quality of the system by refactoring when we see a weakness in the design, we will be able to make it respond to whatever changes turn up. The alternative is the usual “software rot” where the code decays until the team just cannot respond to the needs of its customers. We’ll return to this topic in Chapter 20.

Tuning the Cycle

There’s a balance between exhaustively testing execution paths and testing integration. If we test at too large a grain, the combinatorial explosion of trying all the possible paths through the code will bring development to a halt. Worse, some of those paths, such as throwing obscure exceptions, will be impractical to test from that level. On the other hand, if we test at too fine a grain—just at the class level, for example—the testing will be easier but we’ll miss problems that arise from objects not working together.

How much unit testing should we do, using mock objects to break external dependencies, and how much integration testing? We don’t think there’s a single answer to this question. It depends too much on the context of the team and its environment. The best we can get from the testing part of TDD (which is a lot) is the confidence that we can change the code without breaking it: Fear kills progress. The trick is to make sure that the confidence is justified.

So, we regularly reflect on how well TDD is working for us, identify any weaknesses, and adapt our testing strategy. Fiddly bits of logic might need more unit testing (or, alternatively, simplification); unhandled exceptions might need more integration-level testing; and, unexpected system failures will need more investigation and, possibly, more testing throughout.