Chapter 8. Building on Third-Party Code

Programming today is all about doing science on the parts you have to work with.

—Gerald Jay Sussman

Introduction

We’ve shown how we pull a system’s design into existence: discovering what our objects need and writing interfaces and further objects to meet those needs. This process works well for new functionality. At some point, however, our design will come up against a need that is best met by third-party code: standard APIs, open source libraries, or vendor products. The critical point about third-party code is that we don’t control it, so we cannot use our process to guide its design. Instead, we must focus on the integration between our design and the external code.

In integration, we have an abstraction to implement, discovered while we developed the rest of the feature. With the third-party API pushing back at our design, we must find the best balance between elegance and practical use of someone else’s ideas. We must check that we are using the third-party API correctly, and adjust our abstraction to fit if we find that our assumptions are incorrect.

Only Mock Types That You Own

Don’t Mock Types You Can’t Change

When we use third-party code we often do not have a deep understanding of how it works. Even if we have the source available, we rarely have time to read it thoroughly enough to explore all its quirks. We can read its documentation, which is often incomplete or incorrect. The software may also have bugs that we will need to work around. So, although we know how we want our abstraction to behave, we don’t know if it really does so until we test it in combination with the third-party code.

We also prefer not to change third-party code, even when we have the sources. It’s usually too much trouble to apply private patches every time there’s a new version. If we can’t change an API, then we can’t respond to any design feedback we get from writing unit tests that touch it. Whatever alarm bells the unit tests might be ringing about the awkwardness of an external API, we have to live with it as it stands.

This means that providing mock implementations of third-party types is of limited use when unit-testing the objects that call them. We find that tests that mock external libraries often need to be complex to get the code into the right state for the functionality we need to exercise. The mess in such tests is telling us that the design isn’t right but, instead of fixing the problem by improving the code, we have to carry the extra complexity in both code and test.

A second risk is that we have to be sure that the behavior we stub or mock matches what the external library will actually do. How difficult this is depends on the quality of the library—whether it’s specified (and implemented) well enough for us to be certain that our unit tests are valid. Even if we get it right once, we have to make sure that the tests remain valid when we upgrade the libraries.

Write an Adapter Layer

If we don’t want to mock an external API, how can we test the code that drives it? We will have used TDD to design interfaces for the services our objects need—which will be defined in terms of our objects’ domain, not the external library.

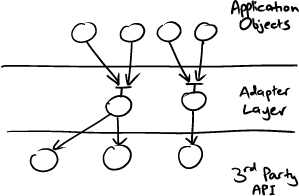

We write a layer of adapter objects (as described in [Gamma94]) that uses the third-party API to implement these interfaces, as in Figure 8.1. We keep this layer as thin as possible, to minimize the amount of potentially brittle and hard-to-test code. We test these adapters with focused integration tests to confirm our understanding of how the third-party API works. There will be relatively few integration tests compared to the number of unit tests, so they should not get in the way of the build even if they’re not as fast as the in-memory unit tests.

Figure 8.1 Mockable adapters to third-party objects

Following this approach consistently produces a set of interfaces that define the relationship between our application and the rest of the world in our application’s terms and discourages low-level technical concepts from leaking into the application domain model. In Chapter 25, we discuss a common example where abstractions in the application’s domain model are implemented using a persistence API.

There are some exceptions where mocking third-party libraries can be helpful. We might use mocks to simulate behavior that is hard to trigger with the real library, such as throwing exceptions. Similarly, we might use mocks to test a sequence of calls, for example making sure that a transaction is rolled back if there’s a failure. There should not be many tests like this in a test suite.

This pattern does not apply to value types because, of course, we don’t need to mock them. We still, however, have to make design decisions about how much to use third-party value types in our code. They might be so fundamental that we just use them directly. Often, however, we want to follow the same principles of isolation as for third-party services, and translate between value types appropriate to the application domain and to the external domain.

Mock Application Objects in Integration Tests

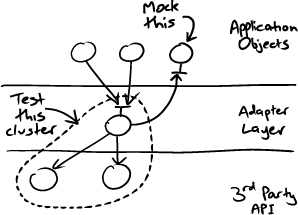

As described above, adapter objects are passive, reacting to calls from our code. Sometimes, adapter objects must call back to objects from the application. Event-based libraries, for example, usually expect the client to provide a callback object to be notified when an event happens. In this case, the application code will give the adapter its own event callback (defined in terms of the application domain). The adapter will then pass an adapter callback to the external library to receive external events and translate them for the application callback.

In these cases, we do use mock objects when testing objects that integrate with third-party code—but only to mock the callback interfaces defined in the application, to verify that the adapter translates events between domains correctly (Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2 Using mock objects in integration tests

Multithreading adds more complication to integration tests. For example, third-party libraries may start background threads to deliver events to the application code, so synchronization is a vital aspect of the design effort of adapter layers; we discuss this further in Chapter 26.