CHAPTER 11

Build, Dismantle, Repeat

“I give the talkies six months more.”

—CHARLIE CHAPLIN, 1931*

A defining critical characteristic for leaders in the Age of Complexity is being able to guide their organizations through the inevitable waves of change. Do new things, and stop doing the things you’ve always done. Sounds simple, but it’s surprisingly hard to do. The business that can do both at the same time is a rare beast. The dynamic has a name: creative destruction, a term coined by Austrian-American economist Joseph Schumpeter to describe the transient nature of competitive advantage. This cycle, as we’ve argued in this book, is accelerating.

Some companies respond to creative destruction by hunkering down behind Castle Walls. They’ve fallen victim to Siren #4. They like being where they are and don’t want anything to change.

Companies may invest heavily in innovation (“adding the new”) or in operational excellence (“optimizing the current state”). But the required counterpart (“taking out the old”), in the form of complexity reduction, tends to be neglected. Why? There are many possible reasons:

![]() The drag of complexity isn’t quantified—companies don’t know how much it is really costing them to “continue the old.”

The drag of complexity isn’t quantified—companies don’t know how much it is really costing them to “continue the old.”

![]() All their attention is on the “new” because it is more interesting than the old.

All their attention is on the “new” because it is more interesting than the old.

![]() The impacts of complexity affect an entire system; the costs therefore don’t fall onto any one person’s lap.

The impacts of complexity affect an entire system; the costs therefore don’t fall onto any one person’s lap.

![]() Established businesses are often power centers, which can create a preservation bias.

Established businesses are often power centers, which can create a preservation bias.

Also, creative destruction has rarely been practiced as a management discipline. While most executives have heard of creative destruction, few have grappled with the practical changes required in mindset and practices in order to surf these waves of transient advantage. What makes sense at the intellectual level can feel very different when you’re living inside it.

The story of how Andy Grove and Gordon Moore shepherded Intel out of a dying market (memory chips) and into a new market (microprocessors) is well known. But the arduous process by which they stopped doing the things they’d always done is worth reflecting upon. In fact, even armed with the correct insight about the future of the market, Grove and his team met resistance in the form of Intel’s “religious dogmas,”1 both of which centered on the importance of memory chips as the backbone of their organization. And Grove himself—known as a bold, decisive leader—admits he was emotionally conflicted about the nature of the change:

To be completely honest about it, as I started to discuss the possibility of getting out of the memory chip business with some of my associates, I had a hard time getting the words out of my mouth without equivocation. It was just too difficult a thing to say. Intel equaled memories in all of our minds. How could we give up our identity? How could we exist as a company that was not in the memory business? It was close to being inconceivable.2

Even if you are not called upon to execute such bet-the-company pivots, it is likely you will find yourself required to exit out of certain markets and businesses and redeploy resources to areas of higher value.

Of course, it doesn’t have to be a wrenching, traumatic experience. Certainly, this is sometimes the necessary medicine when there is a sudden unexpected market shift, or a new competitor makes a surprise entry. But in a transient-advantage world, the onus should be on building capabilities for ongoing weeding and pruning, versus bringing in the bulldozers and earthmovers. In fact, there is evidence that top-performing growth companies tend to do just that. Academic Rita Gunther McGrath recalls that her research assistants, in gathering data on these top-performing companies, found very little evidence of sudden, wrenching exits. Instead, they “seemed to have a knack for integrating their old technologies into new waves.”

So to help you achieve this, we’ll introduce four strategies in this chapter that can help you embrace creative destruction:

![]() Make space through ongoing vigorous pruning.

Make space through ongoing vigorous pruning.

![]() Anchor on customer needs, not assets.

Anchor on customer needs, not assets.

![]() Rethink your business definition.

Rethink your business definition.

![]() Give new ideas room to thrive.

Give new ideas room to thrive.

Make Space Through Ongoing Vigorous Pruning

If companies build a capability for ongoing pruning of their portfolio and a constant monitoring of their market position, they can avoid having to make traumatic exits from a market or segment. But it requires discipline and accurate insights into where value is being created in their business—often a critical gap.

For example, consider one of our clients, “ToolCo,” a major professional tool manufacturer, which had gone through several SKU rationalization exercises in the past. Its efforts targeted removal of the bottom 5 percent of low-volume products, disturbing normal operations, and did not achieve the desired cost reduction benefits because the company did not understand the sources of its profitability.

Our analysis showed that 99 percent of ToolCo’s sales came from just 35 percent of its SKUs, and that most of the low-volume SKUs were unprofitable at the gross margin level. Furthermore, ToolCo’s growth plans required a significant increase in manufacturing capacity and a significant investment in CAPEX.

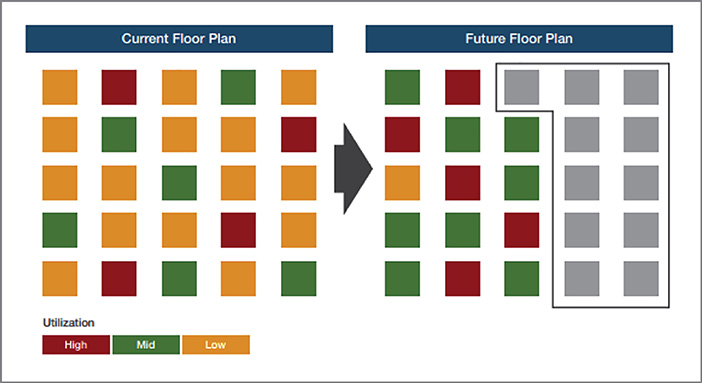

From our complexity analysis, we saw that ToolCo’s low-volume products were consistently undercosted, as high-volume products were disproportionately absorbing the majority of overhead costs. A deeper pruning of its portfolio allowed ToolCo to concentrate its manufacturing in fewer production lines with higher utilization, increasing plant and staff productivity. Plant CAPEX for machinery and floor space was also avoided by redeploying underutilized assets to make room for growth.

The benefits: a 45 percent increase in capacity with minimal investment, and 15 percent EBITDA lift, at just one of its manufacturing plants, with similar results elsewhere in its business. The results of its subsequent changes are shown in Figure 11.1.

FIGURE 11.1: Pruning for Growth. By removing the majority of the low-volume, undercosted products, ToolCo created the capability to grow its other products (or new products) by 45 percent through asset redeployment and floor space utilization of the manufacturing cells.

Anchor on Customers, Not Assets

The word assets has a positive connotation. In a previous age, asset accumulation was a competitive advantage, available to only the biggest companies. Having lots of physical assets presented an insurmountable barrier to entry for any new entrant trying to compete against you. You’ll recall the example of Samuel Insull, who established Chicago Edison’s fortunes by building larger power stations than anyone else and then acquiring competitors to gain further economies of scale.

But in the Age of Complexity, assets can act as anchors, inhibiting change or contorting the future opportunity to fit the current asset footprint. The accumulation of assets can also create an environment where we are more likely to make strategic mistakes. Leaders get trapped in the mindset of a former age, and see assets as a differentiator, as something their organization has that others don’t, and therefore an “advantage.” As a result, they may extend a bias toward strategies that leverage existing assets.

As we have discussed earlier in this book, companies are now able to get access to assets without ownership: for example, on-demand computing through Amazon Web Services, or on-demand manufacturing through network orchestration. Access without ownership enables a faster, more flexible response to market conditions, as the time it would take to shed assets injects delay in decision making and execution. To illustrate the point, consider the time, effort, and deliberation involved in selling and moving to a new house, not a small undertaking. Now compare that to the task of switching hotels.

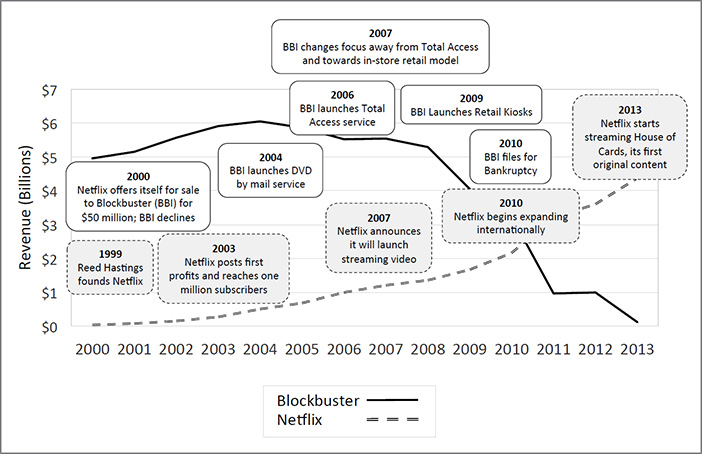

It is difficult to imagine now, but when now-defunct Blockbuster launched its own DVD-by-mail service in 2004, many saw the news as the beginning of the end for then-rival Netflix.

“Blockbuster’s move poses a potentially serious threat to Netflix,” wrote the Wall Street Journal.3 Though Netflix was originally viewed as a niche business—Blockbuster passed on snapping it up for $50 million in 2000—the DVD-by-mail model grew to represent a threat to the Blockbuster’s business. Netflix had pioneered the business model, but Blockbuster enjoyed many advantages. It had a bigger brand and 5,500 locations. Netflix had grown its business to 1.5 million subscribers, but that was dwarfed by Blockbuster’s 48 million accounts.4 So when Blockbuster announced it was getting into the DVD-by-mail game, many assumed it would crush the upstart Netflix.

As we all know, things didn’t quite work out that way. Just six years later, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy, and by 2014 its remaining U.S. stores were shuttered. Netflix meanwhile has gone on to become a $6.7 billion video streaming giant. (See Figure 11.2.)

FIGURE 11.2: The Changing Fortunes of Blockbuster and Netflix

What happened in those intervening years? Blockbuster was led first by John Antioco (CEO from 1997 to 2007) and then Jim Keyes (CEO from 2007 to 2011). Both were well regarded in retail circles as effective leaders with strong track records. And the business was alert to the impending dawn of video-on-demand. Antioco came to recognize the threat from DVD-by-mail and streaming and launched an integrated program called Total Access (also doing away with the troublesome late fees!). But another way of looking at the issue is that Netflix had one business to focus on (video distribution), and Blockbuster had two (video distribution and retail). At one point, video distribution happened via Blockbuster’s retail stores. When that stopped being the case, the retailer essentially had two separate businesses on its hands, with arguably limited synergy.

According to Vijay Govindarajan, a professor at Dartmouth’s Tuck School of Business: “Blockbuster’s cardinal sin . . . was maintaining its commitment to a vast retail network, even when that was no longer the way movie renters wanted to shop.”5

In other words, Blockbuster made strategic decisions based on the assets it had (the retail stores) rather than customer needs.

Rethink Your Business Definition

Were there strategic options that would have improved Blockbuster’s chances?

As access to digital TV shows and films is becoming ubiquitous, it is notable how Amazon and Netflix are producing their own proprietary content as a source of differentiation—a not unthinkable path for Blockbuster had it moved away from its store network to a streaming-only strategy.

Of course, it’s very easy to judge after the fact. As we’ve said in this book, strategies are inexact. But the clearer your view of the situation—and the more you’re aware of the types of traps before you—the better your chances of getting it right. Certainly if Blockbuster had defined its business around the notion of movie experts versus retail or video distribution, it might have come up with different strategies.

Business definition underpins successful strategy. It can not only lead to a more nimble strategic response, but also significantly reduce the sense of trauma that comes with change.

Consider the case of Eastman Kodak, an American icon that filed bankruptcy in 2012 in the wake of the rise of digital cameras and built-in smartphone cameras. At the same time, its chief competitor, Fujifilm, diversified and grew despite the migration to digital technologies. The difference in outcomes can be traced to their adaptability.

Both companies saw that change was coming. Larry Matteson, a former Kodak executive, recalls writing a report in 1979 detailing how different parts of the market would switch from film to digital, starting with government reconnaissance, then professional photography, and finally the mass market, all by 2010 (as reported in the Economist).6

Interestingly, there was a vast difference in how the two firms digested that information. At Kodak, there was “complete and utter denial,” according to one source.7 Steven Sasson, the Kodak engineer who invented the first digital camera in the 1970s, remembers management’s dismay at his feat: “My prototype was big as a toaster, but the technical people loved it. But it was filmless photography, so management’s reaction was, ‘that’s cute—but don’t tell anyone about it.’ ”8

From a margin perspective, the reaction was rational: film was the cash cow, and the longer you could extend its run, the better. But the end of the run was also predictable.

Both firms eventually awoke to the threat. Kodak decided to stick close to home, betting its future on digital imaging (which was more challenging from a profit perspective, and further challenged with the advent of smartphones). Fujifilm, in contrast, took a different path. It adjusted to a new business definition based on its existing pockets of expertise—such as nanotechnology, photosensitive materials, and chemicals—rather than specific products. For example, the company discovered it could exploit its chemical expertise for other markets such as drugs, LCD displays, and cosmetics. (Its knowledge of collagen, which keeps photos from fading due to its antioxidant qualities, was a springboard for an anti-agingskincare product line called Astalift.)

That is not to say that Fujifilm’s transition was painless. “Both Fujifilm and Kodak knew the digital age was surging towards us,” said Fujifilm CEO Shigetaka Komori. “The question was, what to do about it.” Indeed, as part of the restructuring, Fujifilm shut plants and announced layoffs. All told, the restructuring led to the loss of 10,000 jobs and a total charge of ¥350 billion ($3.3 billion).

“The most decisive factor was how drastically we were able to transform our businesses when digitalization occurred,” Komori said.9 When the boat is sinking, he said, no one complains too loudly. Nonetheless, by stretching its business definition away from imaging, Fujifilm was able to map out a path forward that was economically viable while leveraging its existing capabilities.

Give New Ideas Room to Thrive

Disengaging from legacy lines of business is only half the battle. You need new ideas. Ironically, it is not uncommon for emerging businesses to be crowded out by parts of the business that have historically provided the lion’s share of revenue, or to be yanked before they have had a chance to find their feet.

In this regard, startups have a big advantage over larger firms. In the latter, if a new venture is not a hit out of the gate, there is a lot of pressure to abandon the project or let it linger and just move on. Startups, on the other hand, have to succeed, and if the first iteration doesn’t work, their natural instinct is to reinvent and reconfigure until something works. You’ll hear many refer to this as a pivot. This is in stark contrast to many large corporations.

Entrepreneurs are not focused on avoiding the stigma of failure; they are focused on making their business work. To that end, it is not uncommon for startups to spend a lot of time going down blind alleys before finally finding the path to success. Yelp began life as an automated system for e-mailing recommendation requests to friends, a proposition that fell flat. Only when the site allowed users to post reviews about local businesses—an idea that seemed like an interesting feature but hardly a growth engine—did things take off.

In The Lean Startup, Eric Ries discusses what he calls an “overriding challenge” in developing a successful product: “deciding when to pivot and when to persevere.” Many very valuable ideas, businesses, and products have only found their way after: (1) a pivot, which may include switching to a different customer segment, application, channel, etc., and (2) perseverance in spite of a significant setback.

Microsoft experienced this firsthand with its much criticized—then much praised—Surface tablet. It developed its first versions of the Surface tablet in total secrecy using conventional product design and development methodology. It was an interesting concept that failed due to poor execution, both on product features and requirements and technical aspects of product development. The result: a $900 million write-down!

A CNNMoney article explained that “Microsoft didn’t want to tip off its competitors, so it holed the team away in a secret lab and even gave it a meaningless codename, ‘WDS.’ Customers were never asked for feedback—and it showed.”10 Secrecy kept Microsoft from continually engaging with its customers to ensure refinement of the broad convergence concepts that everyone found so appealing. “It was ginormous, essentially eliminating any advantage of being a tablet.” Microsoft has since turned its development methodology completely around and moved to a rapid prototyping model that allows continuous customer engagement during product development. The result, the Surface Pro 3, has been a big success.

“When you look at that writedown and that moment, it was, of course, humbling,” said Panos Panay, head of surface computing. “But Microsoft has been so amazing and not once wavering on its commitment to making amazing products. Not once.”

Microsoft has the resources to stand behind Surface, but nonetheless its continued doubling down on the product until the company got it right is noteworthy. (That’s nonetheless an expensive way to get it right! Did Microsoft forget the lesson from Chapter 10—know when you’re experimenting and when you’re not?) Startups don’t have a billion dollars to burn. Ries suggests reframing the term runway, a term entrepreneurs use to describe the time they have remaining to achieve success before they run out of money. He says:

The true measure of runway is how many pivots a startup has left: the number of opportunities it has to make a fundamental change to its business strategy. Measuring runway through the lens of pivots rather than that of time suggests another way to extend that runway: get to each pivot faster.

What are the implications for large multinational businesses? A primary lesson is that even the best ideas don’t come out of the box perfect. They need nurturing and a lot of testing and reworking until they become hits. So don’t let an initial setback define the ultimate success or failure of a new growth initiative.

Second, ensure that pivots are part of your vocabulary and that of your business. Big companies are naturally burdened with less agility than startups (more layers of decision making, more budgetary controls, more voices in the room). Like a giant ship, they have a slow turn radius. But just as premature abandonment is nonproductive, so too is blind perseverance—automatic pilot that carries you off the edge of the cliff despite the emergence of new information that suggests a course correction is needed. Pivots are part of the discovery process. A good question to ask, therefore, at the beginning of the project is, how many pivots can we afford? That way the topic is at least on the table.*

Evaluating Your Vulnerability

In the examples given in this chapter, none of the changes were like a thunderbolt from a clear blue sky. Blockbuster saw Netflix on the horizon; Kodak and Fujifilm were both aware of the technology changes and what they could mean for their existing businesses. Of course, that is not always the case. A number of businesses, including music distribution and satellite navigation devices, have been upended in rather rapid and dramatic fashion by the arrival of smartphones. But many times, the changes come gradually, or as Andy Grove puts it, “instead of coming in with a bang, approach on little cat feet.”11

The key is, does your organization have the right mindset to observe the changes and subsequently take action?

Frequently, what stops organizations from doing just that are the mental models that deafen them to these subtle changes, or discourage them from taking action. High Castle Walls! So how susceptible are you to ignoring a grave threat?

Consider to what degree the following statements describe the business. The more your business thinking sounds like this, the more vulnerable you are:12

![]() We do resource allocation by business unit, and usually start with last year’s number and adjust accordingly. Resource allocation is one of the best ways as a leader to ensure your business is moving in sync with the market, and to control expansions and manage exits. That is why it is usually a mistake to decentralize resource allocation—as few managers will ask for less budget each year.13 The money becomes hostage to the business unit instead of being smartly reallocated to growth areas. It also underscores the need to do zero-based resource allocation (starting with a clean sheet of paper) versus making it a purely budgetary process (which often starts with last year’s budget, followed by a negotiation for a percentage increase).

We do resource allocation by business unit, and usually start with last year’s number and adjust accordingly. Resource allocation is one of the best ways as a leader to ensure your business is moving in sync with the market, and to control expansions and manage exits. That is why it is usually a mistake to decentralize resource allocation—as few managers will ask for less budget each year.13 The money becomes hostage to the business unit instead of being smartly reallocated to growth areas. It also underscores the need to do zero-based resource allocation (starting with a clean sheet of paper) versus making it a purely budgetary process (which often starts with last year’s budget, followed by a negotiation for a percentage increase).

![]() Before we pursue new opportunities, we ensure that they won’t cannibalize key products or key areas of existing business. It is understandable to be concerned about new competition for your top-selling products and services—even if the competition comes from your own organization. But either you cannibalize your product line, or someone else will. When Amazon launched Marketplace—where third parties could offer used books in direct competition with Amazon’s own listing—there were immediate protests from publishers saying it would undermine sales of new books and from inside Amazon itself, where category managers were now doubly challenged in meeting sales numbers. But Bezos saw this as offering more choices for customers. “Jeff was super clear from the beginning,” said Neil Roseman (a former VP of engineering at Amazon, quoted in The Everything Store). “If somebody else can sell it cheaper than us, we should let them and figure out how they are able to do it.”14

Before we pursue new opportunities, we ensure that they won’t cannibalize key products or key areas of existing business. It is understandable to be concerned about new competition for your top-selling products and services—even if the competition comes from your own organization. But either you cannibalize your product line, or someone else will. When Amazon launched Marketplace—where third parties could offer used books in direct competition with Amazon’s own listing—there were immediate protests from publishers saying it would undermine sales of new books and from inside Amazon itself, where category managers were now doubly challenged in meeting sales numbers. But Bezos saw this as offering more choices for customers. “Jeff was super clear from the beginning,” said Neil Roseman (a former VP of engineering at Amazon, quoted in The Everything Store). “If somebody else can sell it cheaper than us, we should let them and figure out how they are able to do it.”14

![]() Our channel partners are our top priority; we won’t pursue anything that creates channel conflict. Channel conflict has always been a creeping issue for companies working through intermediaries to consumers (such as consumer goods companies distributing through retailers). The challenge: how to keep these intermediaries happy while being attentive to the end consumer, who now has many direct options and unprecedented access to price comparison given the rise of e-commerce and aggressive competitors like Amazon. The activity of “managing” channel conflict represents a source of delay and inefficiency that upstart competitors can exploit with sharp, direct appeals to your consumers.

Our channel partners are our top priority; we won’t pursue anything that creates channel conflict. Channel conflict has always been a creeping issue for companies working through intermediaries to consumers (such as consumer goods companies distributing through retailers). The challenge: how to keep these intermediaries happy while being attentive to the end consumer, who now has many direct options and unprecedented access to price comparison given the rise of e-commerce and aggressive competitors like Amazon. The activity of “managing” channel conflict represents a source of delay and inefficiency that upstart competitors can exploit with sharp, direct appeals to your consumers.

![]() At the end of the day, what matters is incremental revenue. An incremental sale can be good or bad: bad if it creates more complexity and the costs outweigh the revenue; bad if it’s at odds with long-term customer value. When Jim Keyes reintroduced late fees at Blockbuster, he cited the significant profit contribution it represented. But it was one more nail in Blockbuster’s coffin.

At the end of the day, what matters is incremental revenue. An incremental sale can be good or bad: bad if it creates more complexity and the costs outweigh the revenue; bad if it’s at odds with long-term customer value. When Jim Keyes reintroduced late fees at Blockbuster, he cited the significant profit contribution it represented. But it was one more nail in Blockbuster’s coffin.

![]() Our sense of history and corporate legacy strongly influences our strategic decisions. A sense of pride in the accomplishments and legacy of a business is intrinsically a positive, unless it hinders our ability to match the pace of change in the market or takes us further from what customers want. At the end of the day, customers didn’t care about Kodak’s legacy, only Kodak did.

Our sense of history and corporate legacy strongly influences our strategic decisions. A sense of pride in the accomplishments and legacy of a business is intrinsically a positive, unless it hinders our ability to match the pace of change in the market or takes us further from what customers want. At the end of the day, customers didn’t care about Kodak’s legacy, only Kodak did.

If the above statements reflect your organization, then your risk is high. Raise the red flag about these practices. Be vigilant to how they may disguise or downplay disruptive threats.

Your New Starting Point: Plan for a World of Fleeting Advantage

In The End of Competitive Advantage, McGrath writes that within companies that master the cycle of Build, Dismantle, Repeat, “Exits are seen as intelligent and failures as potential harbingers of useful insight.” Moreover, she says, companies develop a rhythm for moving from one area to another, in line with a life cycle. This contrasts with the vast majority of organizations that possess a “presumption of stability,” which she says creates all the wrong reflexes:

It allows for inertia and power to build up along the lines of an existing business model. It allows people to fall into routines and habits of mind. It creates the conditions for turf wars and organizational rigidity. It inhibits innovation. It tends to foster the denial reaction rather than proactive design of a strategic next step. And yet “change management” is seen as an other-than-normal activity, requiring special attention, training and resources.15

In the Age of Complexity, this orientation has to be switched 180 degrees. Presume that you will always have only a transient advantage with whatever you create. Switch the questions that you’re asking as a leader. Instead of “How will we deal with the unexpected?” ask “What can we do so we are always ready for the unexpected?” Instead of “how can we conserve our assets?” or “How can we avoid trauma?” ask, “How can we be positioned to reconfigure easily?”

The bottom line is that markets outperform companies for a very simple reason: they do not yearn for stability and continuity. They are unencumbered by a sense of history, existing relationships, or fear of cannibalizing themselves, elements that can make companies vulnerable to disruption. So, what’s a leader to do? Put the assumption of discontinuity at the center of your strategy-making process, watch out for Castle Walls, and orient your processes and decision making to the reality of transient advantage.

CALL TO ACTION

CALL TO ACTION

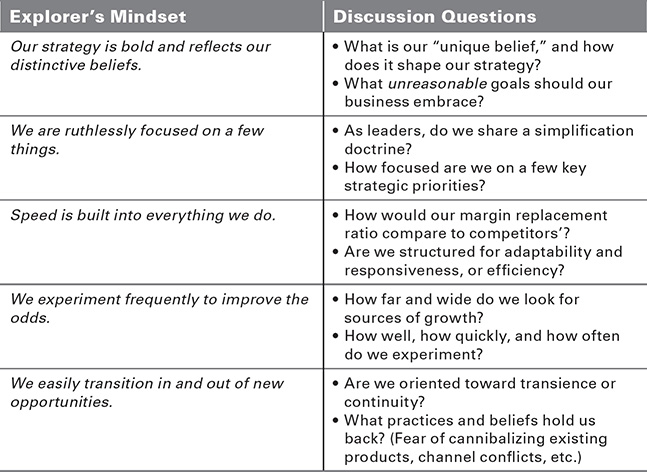

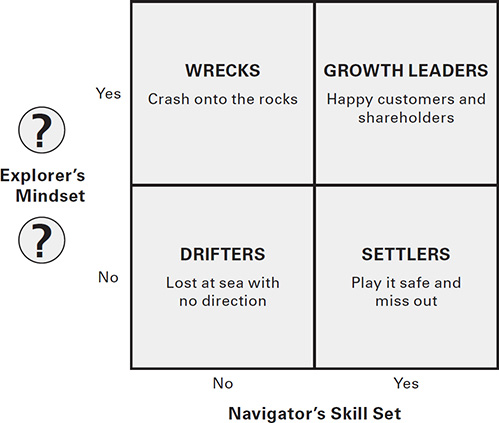

Assess Your Explorer’s Mindset

Opportunity:

We have defined the key components of the Explorer’s Mindset—the mental models that frame how companies approach the pursuit of growth and tend to govern subsequent behaviors. In other words, your culture. Assessing how well your organization reflects the Explorer’s Mindset can reveal potential areas of opportunity and is the first step to building a more assertive growth culture.

Key questions for discussion:

Areas to investigate:

![]() Based on your discussion, and additional review and analysis, plot where you sit on the Explorer’s Mindset axis (see figure).

Based on your discussion, and additional review and analysis, plot where you sit on the Explorer’s Mindset axis (see figure).

![]() Estimate where competitors may be positioned relative to you.

Estimate where competitors may be positioned relative to you.

![]() Identify key areas of focus for targeted improvement.

Identify key areas of focus for targeted improvement.

* The Jazz Singer, the first talking picture, was released four years earlier in 1927, and its success launched a wave of productions in the new format. Despite this trend, Chaplin’s City Lights, a silent picture and reputedly his favorite, was released in 1931 and was nonetheless a commercial and critical success. One journalist wrote, “Nobody in the world but Charlie Chaplin could have done it. He is the only person that has that peculiar something called ‘audience appeal’ in sufficient quality to defy the popular penchant for movies that talk.” It is notable that while Chaplin vehemently resisted the notion that “talkies” were here to stay, he was alone among silent movie stars to find success in the new format. His critique was that it was a narrowing versus expanding art form. He wrote in the Times (as reported in The New Yorker) that “The silent picture, first of all, is a universal means of expression. Talking pictures necessarily have a limited field, they are held down to the particular tongues of particular races.”

* Pivot, Persevere—Kill? In Chapter 10, in discussing how experiments can help develop new growth opportunities, we recommend that you “suspend what’s not working.” But here we are suggesting that you give good ideas a chance, through pivots and persevering. How to reconcile the two? It is not always a straightforward answer. But a couple of principles can help: (1) Know when you are experimenting and when you are not. If it’s the latter, then that implies that you have already developed some market or technical insight that you are betting on, which may warrant continued investment; (2) Be clear about your organizational constraints and capacity, and how many bets you can support. Steve Jobs implies that he might have tried to salvage the Newton if Apple wasn’t in such dire straits. The biggest resource constraint is likely your best people. You’ll have to pick your bets. So if this is outside the future focus of the business, then it may warrant suspension. These are hard choices, but lack of focus will delay development and dilute efforts.