CHAPTER 2

The Age of Complexity

“The historian of science may be tempted to claim that when paradigms change, the world itself changes with them. . . . It is rather as if the professional community had been suddenly transported to another planet where familiar objects are seen in a different light and are joined by unfamiliar ones as well.”

—THOMAS S. KUHN, THE STRUCTURE OF SCIENTIFIC RESOLUTIONS

As labels go, the Age of Complexity may be an understatement. In 2009, we described an example of how choice had exploded in the marketplace:

The consumer packaged goods companies, as suppliers to these retailers, have kept apace, launching a volley of new products: new versions of Oreo cookies, an aisle of potato chips, hundreds of types of toothpaste. The retailers, the consumer goods companies, and their suppliers have all rightly rushed to meet consumer demand, but not without considerable adjustment.1

. . . and the unintended impacts on businesses:

Think about the impact of all that change on the supply chain that “grew up” over many years getting cans of soup from the supplier to the shelf-edge. That same supply chain now has also to support flat-screen TVs . . . now extend across multiple countries . . . now support different format stores, and on and on. . . .

Chances are your business has gone through similar changes. Your business has stretched and grown to meet a decade of growth but has left in its wake an enormous burden of complexity costs.

In the last seven years, things have gotten more complex, not less! Mobile platforms—another channel—were then just emerging. There are now ever more ways to engage with consumers via social media. And the regulatory environment has become more stringent, cumbersome, and confusing, not less so. Whatever your measure, most would agree that our world has become much more complex.

And this increase has been across different dimensions. A lot of the issues that we see companies deal with today fit into the realm of what we call process-organizational complexity. For example, the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program was supposed to save us money. The concept seemed straightforward: by developing one aircraft (albeit in three versions) for the Air Force, Marine Corps, and Navy, as well as many allied nations, development costs would be spread across larger numbers, gaining scale and achieving cost savings.

But a December 2013 Rand Corporation report produced for the U.S. Air Force dismissed the anticipated joint program savings. Amazingly, the report concluded that “the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program will cost more than three single-service programs would have done.”2

The study found that the higher cost-growth rate of joint programs more than offsets their expected savings. According to the study, an ideal two-service program, by doubling the number of aircraft produced, would deliver a maximum savings of 13 percent in unit production costs and 20 percent in overall procurement costs (assuming production costs are four times R&D costs). But in practice these “theoretical savings were more than offset by the greater cost increase rates observed in practice” for joint programs, “making the joint program more costly for both parties.”*

By not anticipating the impact of increased organizational complexity—the massive coordination required across not just the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps, but also across 16 nations—the attempt to reduce one type of rather apparent complexity (the number of different types of aircraft) backfired to lead to a significant increase in a much more insidious type of complexity. Not only is the aircraft more complex itself, but the burgeoning organizational and process complexity has led to significantly higher costs for the overall program.†

Complexity and Growth

So in this context of burgeoning consumer options, the challenge is twofold for companies: simplify to grow, and grow with scale. The Complexity Cube highlights how complexity drives non-value-add cost into organizations. No less real are the impacts of complexity on growth. In fact, complexity impedes growth in many ways:

![]() Impaired service levels. Product and process complexity lead to issues around service, such as poor on-time delivery, quality, or customer service.

Impaired service levels. Product and process complexity lead to issues around service, such as poor on-time delivery, quality, or customer service.

![]() Slowing innovation. A large number of products (or initiatives) actually clog up the development pipeline, slowing time-to-market.

Slowing innovation. A large number of products (or initiatives) actually clog up the development pipeline, slowing time-to-market.

![]() Customer confusion. In the face of higher levels of choice, customers struggle to make purchase decisions and the sales channel is less able to provide support.

Customer confusion. In the face of higher levels of choice, customers struggle to make purchase decisions and the sales channel is less able to provide support.

![]() Higher costs, leading to less margin for reinvestment or higher prices. Complexity costs creep in and working capital goes up, putting pressure on the business.

Higher costs, leading to less margin for reinvestment or higher prices. Complexity costs creep in and working capital goes up, putting pressure on the business.

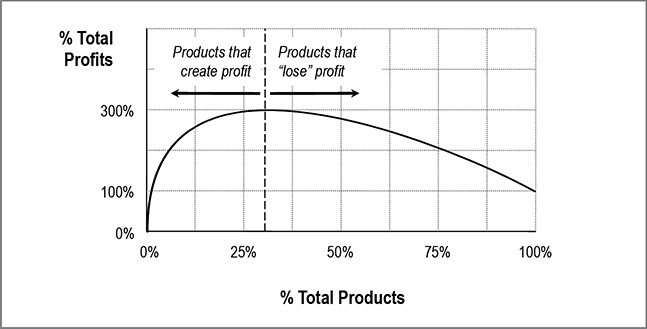

![]() Profit concentration, and risk. Complexity breeds cross-subsidizations, often massive ones, that mask the real creators of value in your company.

Profit concentration, and risk. Complexity breeds cross-subsidizations, often massive ones, that mask the real creators of value in your company.

As the above starts to indicate, complexity has many direct and indirect impacts on your ability to grow. It can quietly but devastatingly consume resources that would be better deployed elsewhere. It can increase your cost base, undermining your ability to fund growth. Not surprisingly, costs and growth are inextricably linked, and that means complexity and growth are too.

Complexity Gains Status

A growing number of CEOs are recognizing the significant challenge that complexity represents. Andy Beal, number 42 on the Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans and chairman and CEO of Beal Bank, one of largest and most successful privately owned financial institutions in the United States, says, “Complexity increases costs and risk of failure. It is a cancer that eats away at efficiency and profitability.”4 And the central topic at the 2013 Global Peter Drucker Forum was managing complexity.

![]() In a recent survey of 1,500 business leaders, complexity was cited as the most significant issue facing leaders today.5

In a recent survey of 1,500 business leaders, complexity was cited as the most significant issue facing leaders today.5

![]() Nearly 80 percent of CEOs in a second survey said they expect higher levels of complexity over the next five years, yet far fewer said they felt prepared.6

Nearly 80 percent of CEOs in a second survey said they expect higher levels of complexity over the next five years, yet far fewer said they felt prepared.6

![]() In a third survey, out of 1,400 global CEOs, nearly 80 percent of CEOs said they have made reducing unnecessary complexity a personal priority.7

In a third survey, out of 1,400 global CEOs, nearly 80 percent of CEOs said they have made reducing unnecessary complexity a personal priority.7

Academics are also recognizing this challenge. In 2008 the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business launched its Center for Complexity in Business. Similarly, in 2011, Suffolk University’s Sawyer Business School launched its Center for Business Complexity and Global Leadership.

But we are not academics. Our insights come from years in the field actually helping clients across numerous industries attack critical cross-functional and systemic issues in their businesses, and one thing is clear to us: complexity isn’t just the latest management fad. This is because complexity isn’t just another tool, or discipline, but the fundamental challenge itself—not just an issue for management to contend with, but one that exacerbates all other management challenges. How did it get this way?

To answer this question it will be helpful to first gain some historical perspective, to view today’s unique challenge within its larger historical context. There are strong undercurrents that have led us to this moment. To successfully navigate the Age of Complexity, it will be very helpful for you to see these currents, and to those we now turn.

The Preindustrial Age

Consider for a moment the world before the Industrial Age, before the advent of factories, steam power, electric utilities, fossil fuels, and the power, mobility, and efficiency that they allow. This was not that long ago. You just need to go back about 200 years, relatively recent in historical terms.

Consider not just what the preindustrial world was, but what it was like to live and work in that world (for many of us, it is difficult to think of life without the Internet, much less the steam engine). For almost everyone it was a hard, backbreaking world. Maury Klein, in his book The Power Makers, provides a vivid description:

Human existence had always been an unrelenting struggle against nature, pitting limited sources of energy against a seemingly endless series of tasks. In early America most people lived on farms that had taken them years to wrench from the wilderness. The farmer had to first clear his land of dense forest by girdling trees, chopping them, pulling up their stumps, and then cutting up the wood for use in building a home and outbuildings as well as for fuel. Rocks and boulders had to be pried up and hauled away to make a fence or simply dumped. . . .

Once a field was cleared, the new farmer could begin his real work. For tools he had a hoe, a plow, and a scythe—staples that would remain in use until the mid-1800s. With a horse or ox as his helper, the farmer spent an exhausting day pushing against the soil to plow maybe an acre. Then he spent the season planting his crop, cultivating it, and finally harvesting it and preparing it for storage. Afterward some crops had to be ground or milled, often by pounding the grain with a mallet. . . .

For his pains the farmer got a simple meal of meat and cornbread washed down with homemade cider or milk if the family had a cow. All of it had to be prepared in tedious rituals: the animals slaughtered, butchered, and salted; the apples picked, dumped into a press, and squeezed. Water had to be hauled in a bucket from a stream or well. The family wore the simplest of garments made from wool or flax. The women of the house toiled for hours spinning, weaving, and cutting clothes for their family, using thread made by twisting short fibers together. Through the long winter months the numbing process of spinning and weaving went on seemingly without end.

Life in the one-room house revolved around the fireplace, which provided heat for warmth and cooking. . . . Feeding the fireplace became one of the most laborious chores of all. A farmer had to cut down an acre of trees to supply enough fuel for a year, and every year the trees were farther away from him. The wood had to be chopped and split to fit the fireplace, hauled to the house, and stacked. Kindling had to be gathered and stored. By one estimate a farmer spent a third of his time during the year doing the chores that provided fuel for the house—and over time the supply around him dwindled rapidly.8

The defining characteristic of the preindustrial world was that work was done through muscle power, whether that of man or beast. In this world, efficiency was driven by the strength or speed of the individual working unit, and this only varied within a narrow biological range from person to person, or from animal to animal.

Relying on muscle power meant that costs therefore were largely variable, meaning that they were proportional to volume of work. For example, 10 horses could do 10 times the work of one horse, but also cost 10 times as much. Hence, the preindustrial world was a variable cost world (see Figure 2.2). This meant that larger companies did not necessarily have significant cost advantages over smaller ones, as there were no significant economies of scale to be had (exceptions existed, of course, but these were largely political and not industrial in nature).

Then the world changed. It began with the Industrial Revolution, a transformation the level of which the world has rarely seen, perhaps akin to the discovery of fire millennia before.*

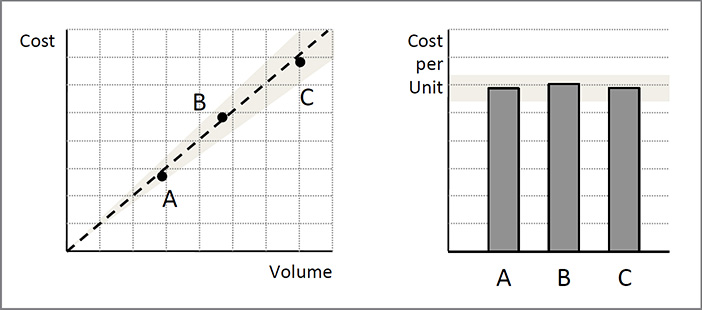

FIGURE 2.2: Cost Curve in the Preindustrial Age. In the Preindustrial Age costs were largely variable, rising in proportion to volume, as shown in the chart on the left. Three companies (A, B, and C) of very different volumes are shown. The chart on the right shows the unit cost for each of these same companies, which only vary within a narrow range despite the relative size differences of these companies (shaded area shown on each chart).

The Industrial Age

The Industrial Age brought with it a level of change that touched almost every aspect of daily life. “Industrialization was not some master plan to remove workers from their century-old tasks. Instead it was a complete reengineering of life based on the ability to provide daily staples at much lower costs” (emphasis added).9

In a relatively short period of time, the steam engine, electricity, and fossil fuels provided significant new sources of power, which offered a whole new world of possibilities. “All the achievements of humanity down to about the eighteenth century were constrained by the inability to find more efficient ways to do things beyond the capacity of muscle and tools that, however ingenious, still required muscle to operate them.”10

The world was finally released from the confining limits of muscle power. Steam, electricity, and fossil fuels enabled new machines and massing of production in the factory. In the factories, massing of production, interchangeable parts, and later the assembly line combined to create ever greater economies of scale. Larger volumes meant more repetitive tasks, which meant greater worker productivity. Larger machines were physically more efficient than smaller ones. Greater productivity and efficiency meant lower prices, which drove greater demand and even larger volumes. Increasing volumes meant ever larger factories, even more powerful machines, and even greater efficiency. Power and production combined in a virtuous cycle that rapidly changed Europe and America.

The key takeaway is that the Industrial Age story was one dominated by fixed costs. Significant fixed-cost investment was required to build ever larger factories and machines, but greater volumes meant greater ability to spread those costs (fixed cost leverage). The result: cost no longer rose proportionately with volume, but improved with volume (see Figure 2.3).

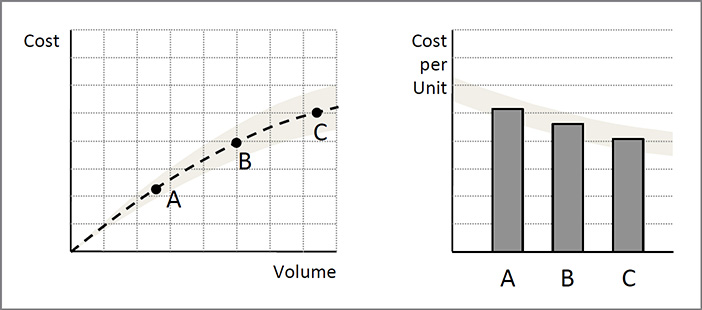

FIGURE 2.3: Cost Curve in the Industrial Age. In the Industrial Age, with economies of scale, costs did not rise as fast as volume, as shown in the chart on the left; three companies (A, B, and C) of very different volumes are shown. Unit cost therefore dropped as volumes grew, as shown in the right-hand chart. Productivity differences were driven by volume more than by differences in the skill of individual workers, as was the case in the Preindustrial Age. Larger companies therefore were naturally more cost competitive than smaller ones.

This was a dramatic and fundamental change. With economies of scale, larger companies now had significant cost advantages over smaller ones! Bigger was now better, and companies such as U.S. Steel, Standard Oil, Westinghouse, and GE raced to be the biggest. This was the story of the Industrial Age.

But the Industrial Age didn’t just shape our world, it shaped how we think. America in particular came “of age” during this era, and the dynamics it brought forth (economies of scale, bigger is better, and so on) were stamped on our psyche. We continue to see the world through this lens, and it is hard to change our wiring. The world has evolved, but our thinking has not kept up.

The Industrial Age did not just stamp itself on how Americans think, but people throughout the West, throughout where the Industrial Revolution spread, and more recently the East, where the Industrial Revolution has played out all over again. (China, in particular, has just experienced its own Industrial Revolution at an incredibly accelerated rate, compressing about 100 years into just a decade.)

The Postindustrial Age—“The Age of Complexity”

We have seen that the world before the Industrial Revolution was dominated by variable costs, with all the limitations that brought. Then in the Industrial Age, fixed-cost leverage became so significant that it became dominant over all else. Strangely, in a way, this simplified things. In the Preindustrial Age, winning depended on nuances. In the Industrial Age, however, winning primarily came down to size. It took initiative, of course, but the first to be the biggest tended to become much bigger.

To understand the Industrial Age, you just have to understand fixed and variable costs. Larger companies were simply more cost efficient than smaller ones, creating a virtuous cycle that reduced prices, accelerated volumes, and carried some companies to amazing heights.

Today, however, we see industry after industry where the largest company is not the most cost efficient, and often quite the opposite. What has changed is that the world has become fantastically more complex—more products, more segments, more channels, more regulations, more sophisticated technology, more complicated processes and organizations, and more sophisticated and demanding customers. This has added to the mix a third category of cost: complexity costs.

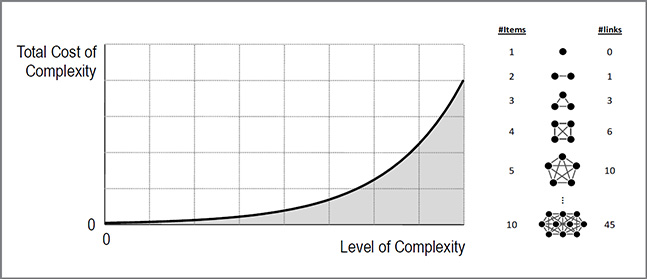

The most important characteristic of complexity costs is that they grow geometrically with complexity. When you double the level of complexity, you more than double the cost of that complexity. Lee Coulter, former SVP of Kraft Foods’ global shared services group, calls complexity a “cube function.” He says, “If I have 10 applications, I may be able to manage them all. If I have 100 applications, managing them is not simply 10 times the complexity—it’s more like 30 times the complexity.”

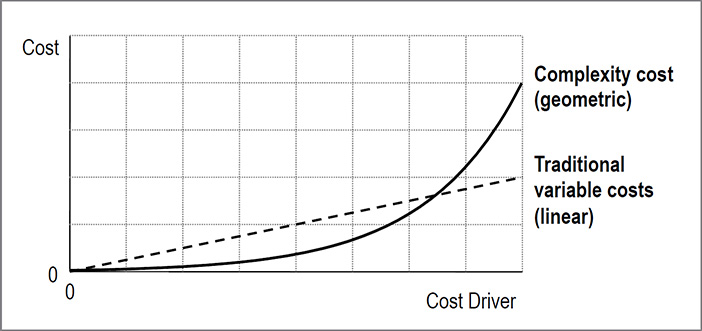

The exponential nature of complexity costs is what makes them so different, and much more insidious and difficult to manage, than the other types of cost (see Figure 2.4). Traditional variable costs are rather linear—costs tend to rise proportionally with volume. With a linear cost, the unit cost is simply the slope of the line ($/volume), making it very easy to think in terms of unit costs.

FIGURE 2.4: Complexity Costs vs. Traditional Variable Costs. The cost of complexity to a company doesn’t grow proportionally with the level of complexity in the company; it grows geometrically or exponentially with the level of complexity. The unit cost of complexity therefore grows as more complexity is added. Traditional variable costs, on the other hand, tend to grow proportionally with volume; and the unit cost remains roughly constant as volume is added.

But with complexity the dynamic is very different: The unit cost of complexity depends on the overall level of complexity (the slope of the line is no longer constant, but changes along the curve), making it much more difficult to think in terms of unit cost. The unit cost of complexity depends on how much complexity has come before it. It also means that the cost of today’s complexity tomorrow will depend on how much more complexity you add.

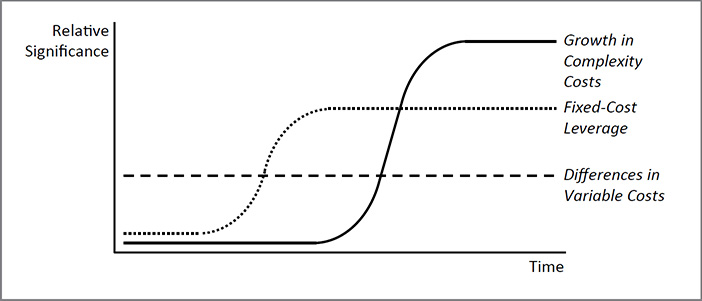

Just as fixed costs dominated the Industrial Age, and variable costs the age before that, complexity costs dominate our current age (see Figure 2.5). This is more difficult to get your head around than a simple fixed/variable view of the world, but it is nonetheless our reality today. Failure to recognize the three types of cost can lead to potentially devastating outcomes.

FIGURE 2.5: Three Types of Cost. There are three types of cost: variable (i.e., proportional with volume), fixed, and complexity costs. They have each always existed, but the relative importance of each has changed significantly over history. In the Preindustrial Age, fixed cost leverage was small, and there was relatively little complexity, leaving differences in variable costs, which were small, to determine companies’ cost structures. In the Industrial Age, fixed cost leverage and resulting economies of scale were the largest determinants of a company’s cost structure. In the Postindustrial Age, with the dramatic rise of complexity, complexity costs tend to be the top driver of a company’s cost structure.

Periods of history can be defined by their dominant characteristics. In each age we discussed, the dynamics themselves were not new, but the relative importance among them certainly was, with significant impact on how companies would compete.

The Preindustrial Age, the Industrial Age, and the Age of Complexity were each very different. Viewed over the span of history, however, the Industrial Age was truly an exception, a remarkably unique and relatively brief period unlike any before or since. Because of its tremendous impact on our world it has stamped itself on how we think—but nonetheless it was an exception.

For a relatively short period of time, a unique combination of technological, political, social, and financial forces came together to launch a self-perpetuating cycle of lower costs and greater consumption (sure, we can still find this trend at work today, certainly in areas such as genomic sequencing and data storage, but these are remarkable stories, not the dominant story of this age). We were freed for the first time on a broad scale from the stifling constraint of muscle power; we enjoyed powerful new forms of energy; social changes released significant amounts of human capital; and financial capital followed suit to lubricate the machine of this new world. Yet the complexity that would ultimately result had not yet arrived. For a brief moment in time, the world had scale, but not complexity. But complexity has arrived, and the world has changed, yet our minds are still stuck in that brief period of time.

Complexity not only affects cost structures, but also how companies compete, which means how they innovate and grow. Yet many companies continue to use outmoded paradigms and frameworks not suited to the present age—akin to navigating dangerous waters with an outdated chart. The tragedy is that despite the best efforts, many companies crash on the rocks.

Just as economy of scale had such a pronounced impact in the Industrial Age, the Complexity Cost Curve, with its exponential growth, has a substantial impact on companies today. It explains why many companies’ cost structures have grown faster than their top line, and it goes to the heart of how complexity is eroding a company’s ability to grow: complexity sucks up resources that can and should be better focused on higher-growth opportunities.

The complexity curve isn’t new, it has always existed, but 50 years ago companies were still on the flat left-hand side of the curve so it could reasonably be ignored. Today however, companies are on the much steeper right-hand side of the curve. This is the new dynamic, the defining dynamic of our time. The Industrial Age was all about economies of scale. The Age of Complexity has brought complexity costs. And these two curves are in a tug of war, with huge implications on both your cost structure and your ability to grow.

* According to Defense News (April 18, 2016), the 60-year estimate to keep F-35s flying until 2070 is now $1.124 trillion.

† It is ironic that it was Kelly Johnson, founder of Lockheed’s famous Skunk Works, who was the leader in understanding the impact of organizational complexity on aircraft development. It is tempting to consider what Johnson would make of the JSF program. One of his 14 rules of management was that “the number of people having any connection with the project must be restricted in an almost vicious manner.” It seems that out of the best intentions the JSF program has gone the other way, and highlights the challenge of complexity and the importance of determining where to build scale.

* Historians debate the precise dates for the beginning and end of the Industrial Revolution, but it was generally between 1760 and 1830.