CHAPTER 4

The Sirens of Growth

“To the Sirens first shalt thou come, who bewitch all men, whosoever shall come to them. . . . Whoso draws nigh them unwittingly and hears the sound of the Sirens’ voice, never doth he see wife or babes stand by him on his return . . . but the Sirens enchant him with their clear song, sitting in the meadow, and all about is a great heap of bones of men.”

—HOMER, THE ODYSSEY1

As a quick refresher on Greek mythology, the Sirens were the enchanting yet dangerous creatures that seduced sailors with beautiful songs, luring them to their deaths as they crashed on rocky shores. In business, we see a similar dynamic: certain growth strategies come to the fore and lure business leaders onto treacherous paths. These strategies seem attractive at the outset, only to lead to destructive outcomes.

As you read the following pages, consider to what degree these Sirens are at the core of your growth strategy, and to what degree they may they be leading you astray. The next chapter discusses ways to resist the Sirens.

Siren #1: The Expanding Portfolio

![]() Customers like variety, so the broader the portfolio the better. That is the mindset behind this Siren. In a world where customers seek choice, companies are responding by offering more options: different sizes, colors, service packages, and so on. Line extensions, for example, offer predictable incremental revenue because customers are already familiar with the earlier version of the product.

Customers like variety, so the broader the portfolio the better. That is the mindset behind this Siren. In a world where customers seek choice, companies are responding by offering more options: different sizes, colors, service packages, and so on. Line extensions, for example, offer predictable incremental revenue because customers are already familiar with the earlier version of the product.

For many, proliferation and ever-expanding portfolios have become a business norm. Retailers press consumer packaged goods manufacturers for distinctive packaging, sizing, and branding to create “difference” against competitors. Consumer goods companies deliver an incremental new product (different flavor, packaging, platform, and so on) to try to drive top-line results.

This is a powerful Siren, with a rational underpinning: the more you segment demand, the more specifically you can match differing customer tastes, and thus the more you’ll spur growth.

It sounds reasonable, but is it true? Research suggests that for most situations the answer is no. Rather, it is true up to a complexity threshold, the point beyond which product variety actually impairs sales performance. For example, in a study entitled “Too Much of a Good Thing,” researchers looked at three years of data from 108 distribution centers of a major soft drink bottler to understand the impact of product variety on sales. The authors looked at the positive and negative impacts of variety and the relationship to sales rates. They conclude: “Product variety initially leads to increases in sales, as increased product variety appeals to variety-seeking consumers. However, the increases in sales are at a diminishing rate due to cannibalization as variety increases.”2

Once variety reaches a certain optimal level, the negative impacts on fill rates and operations, as well as inherent product cannibalization, outweigh the positive benefits. “Thus, an increase in product variety actually reduces sales performance beyond this optimal level” [emphasis ours].

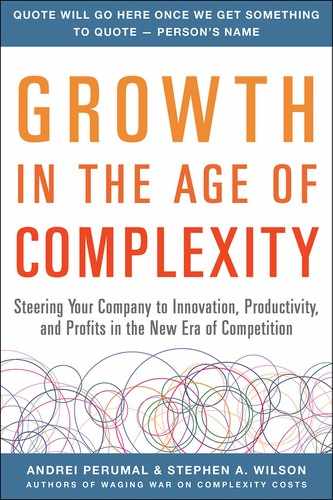

Fifty years ago, most organizations had far smaller portfolios, and were therefore a safe distance from this complexity threshold. During that era, the benefits of expanding the portfolio outweighed the costs. But unfortunately many companies today are well beyond this point (Figure 4.1).

FIGURE 4.1: The Complexity Threshold

There are other organizational impacts to consider as well. Consider a VP of sales contending with hundreds of segments and 200,000 products. Strong product knowledge? Not a chance! An easy buying process for your customers? Very unlikely. Good salespeople will pare down what they pitch to a more manageable breadth. But when every salesperson does this—sampling a different subset of the portfolio—the result is that you carry all the cost of the variety but get none of the benefits. (We call this the buffet effect, similar to how you sample certain dishes in the buffet line.) It also effectively delegates portfolio strategy down to the sales force. Thus, proliferating portfolios often take hold in the absence of well-defined customer or product-level strategy.

In our work with industrial companies, it is striking how similar their stories are: a company built around a single engineering innovation that yielded decades of solid growth by responding to specific customer requests, also creating a nice barrier to entry against newcomers who could not compete across such a broad range of items. Then came a moment of crises: falling sales, increasing costs. What changed? Well, being all things to all people is no longer a viable strategy. Customers now have greater choice and greater visibility to pricing, creating a very different buying mindset: What does this company do uniquely well? That is what I’ll pay for.

Proliferation is a difficult habit to break, for a very good reason: it worked in the past. One-stop shopping! Everything the customer needs! Companies that allowed proliferation in their portfolios often accrued some additional sales. That fed into sales targets, bonus plans, and a general sense of accomplishment. But what is less visible is the cannibalization of existing sales and the introduction of the additional costs of complexity. The bias is toward what companies can easily see and measure, so they happily keep on proliferating, cannibalizing existing sales, and increasing their costs. But that way madness lies!

Rubbermaid, the well-known maker of many kitchen items, befell such a fate after a spate of proliferation led to its stumbling and eventual purchase by Newell in late 1998. It was a fall from grace described by Fortune as the turning of a “purebred into a howling mutt almost overnight.”3 In fact, rapid portfolio expansion was central to Rubbermaid’s strategy: “Our objective is to bury competitors with such a profusion of products that they can’t copy us,” said then-CEO Wolfgang Schmitt.4 Unfortunately, it wasn’t just the competitors who were buried! As its product line grew to 5,000 SKUs, Rubbermaid’s ability to meet customer expectations deteriorated. “They’ve been such lousy shippers. Not on time, terrible fill rates, and their products cost too much,” reported one retailer.5 Couple this poor performance with additional growth initiatives, ambitious overseas expansion projects, and a severe spike in raw material costs, and the result was the decline of a company that had enjoyed a sterling reputation for almost 80 years.

As Rubbermaid learned, the Siren of the Expanding Portfolio can lead to near-annihilation. Fortunately, such tales of complete disaster are thankfully rare, but the impacts of this Siren are nonetheless crippling to growth, with the resulting complexity impairing critical service levels, confusing customers, and dissipating limited growth resources across an unfocused portfolio.

At what point does more become less? To what degree are the often hidden impacts of unrestrained portfolio expansion undermining expected benefits and more broadly your growth objectives? In today’s increasingly crowded marketplace, how does a strategy of continuously expanding the portfolio of products and services support the goals of differentiation and market leadership?

What Makes Us Susceptible to the Expanding Portfolio Siren?

Contributing mindsets:

![]() More is better than less.

More is better than less.

![]() Whatever the customer asks for.

Whatever the customer asks for.

![]() Let’s see what sticks.

Let’s see what sticks.

Contributing conditions:

![]() Heavy focus on contribution margin—incorrectly assumes that an expanding portfolio has no impact on selling, general, and administrative expenses (SG&A)*

Heavy focus on contribution margin—incorrectly assumes that an expanding portfolio has no impact on selling, general, and administrative expenses (SG&A)*

![]() Revenue rather than profits as basis for sales force compensation

Revenue rather than profits as basis for sales force compensation

![]() Lack of strategic focus and customer segmentation

Lack of strategic focus and customer segmentation

![]() Siloed organizational structure

Siloed organizational structure

Siren #2: The Greener Pasture

![]() How many of us, glancing through the Wall Street Journal in the morning, have momentarily wished that we were operating in a different industry—one in which the profits are richer, the growth curve is steeper, or where the competition is (we believe) less fierce than in our own? Or conversely, when business is good, who resists the temptation to consider a neighboring market with a sense of invincibility? We think, We are doing well here; we can do well over there!

How many of us, glancing through the Wall Street Journal in the morning, have momentarily wished that we were operating in a different industry—one in which the profits are richer, the growth curve is steeper, or where the competition is (we believe) less fierce than in our own? Or conversely, when business is good, who resists the temptation to consider a neighboring market with a sense of invincibility? We think, We are doing well here; we can do well over there!

In both cases, the temptation is to move outside our core markets. Indeed, what better way to drive additional growth and top-line sales than by leveraging current capabilities across a new market, a new product segment, or identifying and capturing an adjacency opportunity? As market competition at home intensifies, new markets appear to be “blue ocean” opportunities—areas that are less crowded with players and therefore offer a better chance for market leadership. Going outside a core market may also represent the logical expansion of a territory: if you have the leading position at home, why not easily capture new areas abroad?

Unfortunately, great success in one arena is rarely a guarantee of success elsewhere. Only one athlete has been an All-Star in two major American sports.6 The stacked odds do little to discourage companies, however, particularly when the issue is corporate growth. When faced with a static market, it is often necessary to look outside. Given the challenges frequently experienced on home turf, companies are tempted to think that a new arena will be friendlier.

Thus, the second Siren is the Greener Pasture: the temptation to stray away from core markets and segments into new areas that appear to be more easily or just as winnable—yet ultimately yield dilution and complexity. There is no shortage of businesses that with lots of energy reached beyond their current market only to retrench years later. Best Buy launched in the United Kingdom only to retreat. U.K. grocer Tesco, going the other direction, fared no better with its U.S. venture.

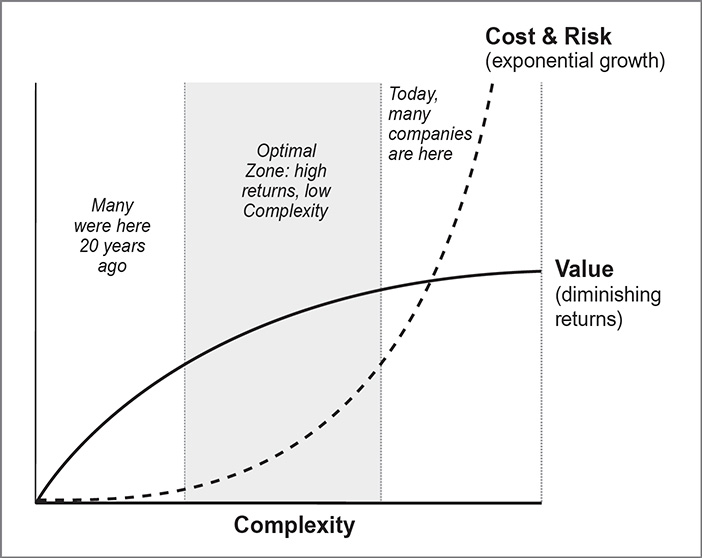

Another case in point: banana producer Chiquita took on a lot of complexity as it looked to new markets. In fact, over a period of 10 years, it lived through a cycle of expansion into new markets, followed by quick retrenchment to the core businesses in the face of poor results.

Under the leadership of CEO Fernando Aguirre, Chiquita expanded its business aggressively into new ventures, including fruit chips, fruit smoothies in Europe, and additional business lines. At the core of this decision was a “grass is greener” moment: looking over at the world of consumer packaged goods and seeing a business better insulated against the commodity cycle. But this diversification strategy, beginning in 2004, required significant R&D, infrastructure, and consumer marketing investment, which diverted funds from the core business, reducing core competitiveness. It also, according to Chiquita, resulted in the business ignoring the private-label salad business and other opportunities in the core.7 In sum, its diversification strategy, born of a desire to seek out some defense against the commodity cycle of bananas, instead yielded complexity and impaired financial results. Revenues slipped from $3.4 billion in 2009 to $3.0 billion in 2012. Earnings fell from $219 million to just $70 million (Figure 4.2).

FIGURE 4.2: Chiquita Share Price and EPS Performance, 2004–2014

Source: Stock and Index Prices and EPS AS REPORTED: Datastream (provided by Thomson Reuters), as at 24 November 2014; EPS figures are absolute figures for the period in which the date falls i.e. EPS at 1 May 2013 = Full Year 2013 EPS

In 2012, Chiquita’s directors decided to replace Aguirre “due to dissatisfaction over the company’s lengthy earnings decline.”8 Aguirre’s successor, Ed Lonergan, formerly with Gillette and Diversey, was brought in to reverse the decline and restore focus on the company’s core business, bananas and salads.9 The company has since exited noncore businesses, including grapes and pineapples, and returned the cost structure to a more sustainable level (targeting SG&A, marketing, and value chain costs) as part of a strategic transformation to focus on core business profit growth.

What happened to Chiquita illustrates why this Siren is so seductive. Executives may overestimate the potential market opportunity or underestimate competitive response to a new entry. Frequently, companies do not foresee how new ventures will impact the existing business with the onslaught of increased complexity. But perhaps the most common reason is a lack of understanding or information as to whether the company has the right skills, structures, and assets to win in the new market—or what has made the company successful in its core market in the first place.

In Chapter 1, we introduced the example of Ames Department Stores, which in the 1970s was a competitor to Walmart, but launched a series of acquisitions, new ventures, and deviation from its formerly successful formula serving rural markets. The result: the company eventually fell into bankruptcy, while Walmart went on to successfully and persistently execute its rural strategy.10

One could say that while Ames (in the 1970s) had to work hard to overreach, the task nowadays is mind-bogglingly easy. Capital is cheap, enabling the pursuit of acquisitions. The globalization of markets leads us to focus more on the similarities than differences in overseas markets, encouraging geographic expansion. And convergence is leading many organizations to question the boundaries of their industry. So expanding beyond the core is increasingly feasible—and enticing.

What Makes Us Susceptible to the Greener Pasture Siren?

Contributing mindsets:

![]() We won at home; we will do great over there, too.

We won at home; we will do great over there, too.

![]() This is a natural growth adjacency for us.

This is a natural growth adjacency for us.

![]() Competition is less tough elsewhere.

Competition is less tough elsewhere.

Contributing conditions:

![]() Top-line focus

Top-line focus

![]() Pursuing M&A for market diversification

Pursuing M&A for market diversification

![]() Unclear strategy; fuzzy definition of “where we play” and “how we play”

Unclear strategy; fuzzy definition of “where we play” and “how we play”

![]() Global ambitions

Global ambitions

Siren #3: The Smash Hit

“I don’t think this (failure) is an option. We really have to deliver the product that they expect.”

—BLACKBERRY CEO THORSTEN HEINS AT LAUNCH OF THE BLACKBERRY 10 MOBILE OS12

“The assumption we work to is that every week [that a new phone is in the market], we lose one percent of price.”

—SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS CEO DR. OH-HYUN KWON13

![]() A smash hit, a blockbuster, a knockout! Magic words to any company, whether you happen to be developing new drugs or producing summer movies. But while everyone welcomes the notion of outsized success in response to its offerings, it is dangerous to build a business strategy around winning the lottery.

A smash hit, a blockbuster, a knockout! Magic words to any company, whether you happen to be developing new drugs or producing summer movies. But while everyone welcomes the notion of outsized success in response to its offerings, it is dangerous to build a business strategy around winning the lottery.

But some do. Perhaps worse, some find themselves in a position where only a blockbuster will suffice. Discussing the recall of Merck’s painkiller drug Vioxx, following the emergence of data that indicated it elevated the risk of heart attack and stroke, Jim Collins said, “My point is not to argue that Merck’s leaders were villains seeking profits at the expense of patient lives or, conversely, that they were heroes who courageously removed a hugely profitable product without anyone requiring that they do so. Nor is my point that Merck made a mistake by pursuing a blockbuster. . . . My point, rather, is that Merck committed itself to attaining such huge growth that Vioxx had to be a blockbuster.”14

The problem is clear. In a world where sustainable differentiation is increasingly rare, most companies are operating in a “horse race” where advantage goes to the company that can stay a nose-length ahead. If you frame success around your ability to land a Smash Hit, and if you corral your activities to improve your odds of doing so, you may neglect other more core activities—the very processes and assets critical for repeatedly finding differentiation.

Those who bet the farm on a singular smash hit frequently find themselves exposed to rapid commoditization (while they fish for a big hit), disconnected from customers (as an ivory tower mentality takes over), and flat-footed (while other competitors embrace the drumbeat of commoditization and focus on improving their speed to market). It can also lead to an almost indiscriminate lack of focus—roll the dice in hopes of one success—conjuring up the Siren of the Expanding Portfolio.

Many fashion retailers, particularly those dubbed “fast fashion” who rapidly bring new designs to stores, have long recognized the futility of chasing a Smash Hit. What matters today is speed to market, the ability to win customer preference, and the capabilities to repeat this time after time. But even in fashion, where the pace has been relentless, the pace is accelerating. The norm used to be that retailers worked to a two-season calendar. Now the focus is on rapid customer feedback and the ability to react to it almost instantaneously. Global retailer Inditex, with many brands including Zara, develops 12,000 different designs each year, 80 percent of which are produced in response to data collected in-store, and none of it driven by a seasonal basis; rather, designs are produced 12 months of the year.15

Accelerating life cycles are not the sole domain of this one industry. The pace of commoditization is increasing across myriad industries, due to many macro forces, such as increased consumer power and the growth in online commerce, new competition in the form of nontraditional market entrants, and the “flat world” effects of globalization. In the past, one big hit could secure a nice annuity. In 1978, Sony introduced its first Walkman, a portable audiocassette player, which gained popularity and widespread use through the 1980s and 1990s, only facing technological obsolescence with competition from CDs (still long before the iPod).16 Today, a 20-year run would be unfathomable, as reflected in Dr. Kwon’s assumption (at Samsung Electronics) that “every week . . . we lose one percent of price.”

One could argue that today, many more companies need to learn from fast fashion and embrace the notion of the “horse race” marketplace. Very few of us have fully acknowledged the leap in skills, mindsets, and structures required to compete in faster life cycle environments. The Smash Hit still holds great allure; but its ability to provide sustaining advantage has been diminished, requiring a shift to a different way of operating.

What Makes Us Susceptible to the Smash Hit Siren?

Contributing mindsets:

![]() A single thing will determine our success; let’s roll the dice.

A single thing will determine our success; let’s roll the dice.

![]() Bet the farm; this has to succeed.

Bet the farm; this has to succeed.

![]() If we can just find a differentiated product.

If we can just find a differentiated product.

Contributing conditions:

![]() Business legacy, launched around a successful product

Business legacy, launched around a successful product

![]() Internal focus—lack of focus on customers

Internal focus—lack of focus on customers

![]() Lack of strategic clarity

Lack of strategic clarity

![]() External pressures, creating go-for-broke mentality

External pressures, creating go-for-broke mentality

Siren #4. The Castle Walls

![]() The Middle Ages was a period of warfare-driven innovation. For every fortification enhancement designed to keep the castle impenetrable, invaders were thinking up new ways of breaching it or laying siege. By the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the stone castle had become a feature of the European landscape, with its accumulated innovations: the drawbridge and moat, the battlements, towers, and most notably, high and thick stone walls. This was the “Age of Castles.”17 But by the early fifteenth century, changes were afoot in military strategy and the norm shifted to construction of lower walls.

The Middle Ages was a period of warfare-driven innovation. For every fortification enhancement designed to keep the castle impenetrable, invaders were thinking up new ways of breaching it or laying siege. By the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the stone castle had become a feature of the European landscape, with its accumulated innovations: the drawbridge and moat, the battlements, towers, and most notably, high and thick stone walls. This was the “Age of Castles.”17 But by the early fifteenth century, changes were afoot in military strategy and the norm shifted to construction of lower walls.

To understand why, it is helpful to understand why walls moved higher in the first place. It was partly the advent of the trebuchet—a type of catapult—and the frequent use of tunneling to destroy castle foundations that led to higher and thicker castle walls in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. But once another innovation appeared—the cannon—the walls no longer offered a defense. Niccolo Machiavelli wrote, “There is no wall, whatever its thickness that artillery will not destroy in only a few days.”18 Moreover, high walls imposed vulnerability, as the big walls made generous targets. Frequently, attackers would attack the base of the walls, causing them to collapse on themselves. In addition, given that high walls were generally thinner at the top, there was no place to mount a cannon, and artillery mounted high was less effective than artillery placed at a lower level. So it was not just that the high castle walls were no longer a good defense against the new technology; the high walls were also a barrier to using that technology offensively.

The analogy extends to companies today. “The list of once-storied organizations that are either gone or are no longer relevant is a long one,” says Rita Gunther McGrath in The End of Competitive Advantage. “Their downfall is a predictable outcome of practices that are designed around the concept of sustainable competitive advantage. The fundamental problem is that deeply ingrained structures and systems designed to extract maximum value from a competitive advantage become a liability when the environment requires instead the capacity to surf through waves of short-lived opportunities.”

The dynamic of creative destruction is not new, but the challenge in the Age of Complexity is that the pace of it is accelerating dramatically. According to a recent BCG study, businesses are moving through their life cycles twice as quickly as they did 30 years ago.19 Moreover, this trend was observed across sectors, and neither scale nor experience provided protection. If companies ambled toward reinventing themselves in the past (including deconstructing what were formerly sources of advantage), they’d better be sprinting today. Even at the best of times, this is an uncomfortable process if you are in the middle of it: How many BU heads will ask for less funding for next year because they see diminished market prospects?

Hence, the power of this Siren is rooted in a powerful dynamic: human behavior. “A preference for equilibrium and stability means that many shifts in the marketplace are met by business leaders denying these shifts mean anything negative for them,” says McGrath. True, it may be unfair (or at least too easy) to point to these scenarios in hindsight. But the question remains: Who of us is not operating in an industry that is vulnerable to disruption? And how are we each ensuring that normal behavioral tendencies—Optimism bias! Preference for equilibrium!—don’t leave us flat-footed. This includes management consulting! In his Harvard Business Review article “Consulting on the Edge of Disruption,” Clayton Christensen and his coauthors describe how “the consultants we spoke with who rejected the notion of disruption in their industry . . . pointed to the purported impermeability of their brands and reputations. They claimed that too many things could never be commoditized in consulting.” And he went on: “We are familiar with these objections—and not at all swayed by them. If our long study of disruption has led us to any universal conclusion, it is that every industry will eventually face it.”20

What Makes Us Susceptible to the Castle Walls Siren?

Contributing mindsets:

![]() We like where we are, it has served us well.

We like where we are, it has served us well.

![]() Declining margins are a short-term blip.

Declining margins are a short-term blip.

![]() Customers want quality, not a low-priced knockoff.

Customers want quality, not a low-priced knockoff.

Contributing conditions:

![]() Strategic focus on sustaining barriers to entry in your market

Strategic focus on sustaining barriers to entry in your market

![]() Lack of experimentation and customer focus

Lack of experimentation and customer focus

![]() Tolerance for margin erosion

Tolerance for margin erosion

The Need for a New Mental Model

The Sirens are archetypes, the four most common growth traps we see companies succumbing to. In a complex world, we must rely increasingly on mental models and rules of thumb to help us execute against our strategies and wade through a sea of data. We already operate with such rules of thumb, but unfortunately many are out of date, and are rooted in a simpler world: all revenue is good revenue; more is better than less, and so on. So an updating of these rules is necessary: we need a different frame of reference, and a new mindset, for a more complex world. Absent this, we fall prey to the Siren Song.

* Our view is that tactical decisions should be made with a contribution margin focus, and strategic decisions with an operating profit focus. Portfolio decisions are strategic in nature.