CHAPTER 10

Improve the Odds

“There are two ways to get fired from Harrah’s: stealing from the company, or failing to include a proper control group in your business experiment.”1

—GARY LOVEMAN, HARRAH’S ENTERTAINMENT CEO

The very first Siren we discussed in Chapter 4 was the Expanding Portfolio. This Siren may be one of the most attractive because it promises success while staying close to home. It is the potent combination of two thoughts that creates the pull: (1) most new products fail, and (2) a slightly different version of a successful existing product is likely to sell at least something.

These statements ignore the fact that incremental line extensions may also cannibalize existing sales and such moves are unlikely to launch you into another echelon of growth. But the thought of “some” success while staying inside a protected harbor is a powerful allure.

Boldness, as we’ve discussed, is the antidote to this. But betting the farm is rarely a good strategy in business or at the casino, as it limits your time at the table. So the real question you should be asking is, How can I improve the odds of discovering rich new sources of growth?

The answer lies in a mindset and accompanying set of behaviors that can help bridge the gap from yesterday’s more linear world to today’s world in which a high degree of interconnectedness makes predicting winners incredibly difficult. It boils down to three behaviors:

1. Cast a wider net for sources of growth.

2. Focus on inventing new business models, not just products and services.

3. Use experimentation to rapidly find more winners.

Element #1: Cast a Wider Net for Sources of Growth

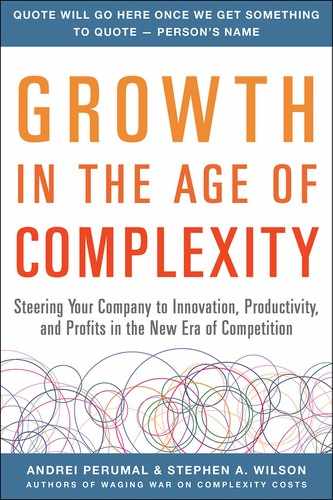

In an environment where there is relative stability and predictability, continuing to tap the same sources for new ideas may well suffice. As captured in Figure 10.1, companies may look inside their industry, using classic stage-gate new product development processes and gathering intelligence about what competitors are doing. They also look outside, exploring adjacent industries or acquisitions where there may be synergy.

FIGURE 10.1: Sources of Growth Ideas (Stable Environment)

All of these traditional approaches still play an important role, particularly in high-dollar capital projects, where the outcomes are more predictable at the outset and where risk-management is critical. Under these circumstances, a stage-gate process manages risks and ensures that what emerges is a functioning solution.

However, the complexity of today’s market is challenging the relative value of traditional approaches, the linear structures or “simple platforms” that have traditionally generated new growth ideas. We are entering what Google’s lead economist Hal Varian calls a period of combinatorial innovation:

If you look historically, you’ll find periods in history where there would be the availability of different component parts that innovators could combine or recombine to create new inventions. In the 1800s, it was interchangeable parts. In 1920, it was electronics. In the 1970s, it was integrated circuits. Now what we see is a period where you have Internet components, where you have software, protocols, languages, and capabilities to combine these component parts in ways that create totally new innovations.2

The opportunity for combinatorial innovation is open to all industries, not just computing. Clearly the advances in computing power, in combination with the technology of your industry, offer tantalizing opportunities if you allow them to propagate. Once upon a time, a company needed to be well established before it could gain access to economical large-scale computing power. Now the playing field has been leveled with operations like Amazon Web Services, which reportedly adds—every day!—physical server capacity equivalent to the amount needed to support Amazon.com when it was a $7 billion annual revenue company, scale that enables startups to access computing power on demand. Such shifts in landscape mean that many existing businesses are vulnerable to disruption. Think of Square in the payment processing industry, Uber in transportation, and Netflix in entertainment content development and distribution. In a combinatorial world, two trends emerge:

![]() Completely new competitors appear, potentially posing existential threats.

Completely new competitors appear, potentially posing existential threats.

![]() The innovation that spurs step-change growth is more likely to come from outside your traditional competitor set than from within it.

The innovation that spurs step-change growth is more likely to come from outside your traditional competitor set than from within it.

To increase your odds of finding new sources of growth, therefore, you need to cast a wider net in your search for new ideas. Challenge yourself: Does innovation only come from the NPD process or from the engineer working on the front line? From asking customers through interviews and surveys or from watching how they actually use your product? From within your industry or from outside?

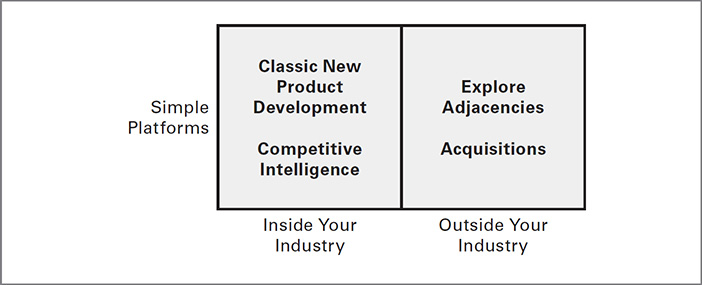

Even within your industry, there are ways to tap into new ideas you might otherwise have overlooked. And there are relatively simple things you can do to reach beyond your own boundaries. These methods are summarized in the top of Figure 10.2 and discussed below.

FIGURE 10.2: Sources of Growth Ideas (Complex Environment)

Architect the Culture

Frequently seen as ethereal rather than something that be engineered, culture is often approached passively instead of proactively. Culture isn’t neutral, you are on one side of the fence or the other, and it isn’t ethereal. While culture involves values and beliefs, it is difficult to measure those. A more practical definition of culture, one that can be more directly measured, is that culture is the collection of organizational practices, norms, and behaviors that define one group as distinct from another.

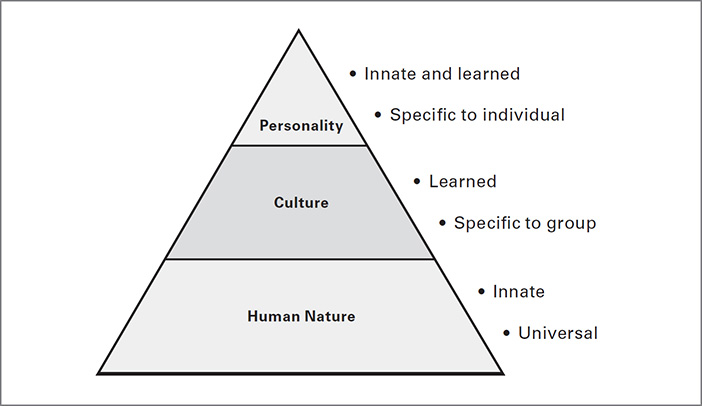

Culture fits right between personality and human nature, as shown in Figure 10.3. Personality is specific to the individual, and is both innate and learned. Human nature, on the other hand, is universal and innate. Culture differs from both personality and human nature in that it’s entirely learned and specific to a group. That group is your company. The very best organizations in every industry are very deliberate about their culture. They take an active role in managing their culture to keep it healthy, and they design and build their desired culture into the company.

FIGURE 10.3: Culture Sits Between Personality and Human Nature

Source: Hofstede, Hofstede, and Minkov, Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, third ed., 2010

A key test for your culture “blueprint” is to assess to what degree do the organizational practices and behaviors support or erode tapping new sources of growth—that is, will your current culture help or hinder your efforts in the top two quadrants in Figure 10.2?

Google’s Eric Schmidt describes an early experience that illustrates the power of culture to drive innovation. In May 2002, Larry Page discovered that many ads that popped up on a Google search were completely unrelated to the search theme. Instead of calling the person responsible or convening a meeting, he printed out the pages of poor-quality results, highlighted the offending ads, and posted the pages on a bulletin board. He then “wrote THESE ADS SUCK in big letters across the top. Then he went home.”

A group of engineers (none of whom were even on the ads team) saw Page’s note, agreed with his succinct analysis of the ads, and went to work on the issue over the weekend. By the following Monday, they sent out an e-mail that “included a detailed analysis of why the problem was occurring, described the solution, included a link to a prototype implementation of the solution the five had coded over the weekend, and provided sample results that demonstrated how the new prototype was an improvement over the then-current system.”3 The gist of their insight—that ads should be placed based on relevancy—became the basis for Google’s AdWords, a multibillion-dollar business.

To begin architecting culture, leaders need to understand how to change behaviors. What we believe drives how we behave, but it is very hard to move culture by first focusing on changing beliefs in order to drive behaviors. But it is possible to do the reverse: focus on consequences (which can be positive or negative) to drive behaviors, which ultimately start to change beliefs. Action begets belief more than the other way around.

Get Ideas in Front of Customers

Software developers have embraced Agile development practices because of hard-earned lessons: customers are notoriously unreliable at telling you what they think they would like, and the best way to get useful information is to put an actual product in their hands to see what they actually like.

While rapid customer engagement has now become a fixture of software development, it is equally important in other areas. Luckily, it is increasingly feasible as rapid prototyping tools such as 3D printing (or “additive manufacturing”) gain prominence. This approach has come a long way from its roots, and today, can handle materials ranging from titanium to human cartilage.”4

Don’t think that rapid prototyping is restricted to physical products, either. With a little bit of creativity (and perhaps some software support), you can create mock experiences where customers can see what new services would be like.

In both cases, the basic technique involves offering different configurations of a product or service to different sets of customers in order to gather feedback on preferences. This both reduces risk in the new product launch and accelerates the time to market.

Hire In and Partner

Says Rita Gunter McGrath in The End of Competitive Advantage: “In a situation replete with complexity and unpredictability, one never knows where the next important idea will emerge. If the senior team is very homogenous, it limits the amount of mental territory that they can cover.”

If new ideas are more likely to appear outside your industry than within it, then you need to find ways to bring novel ideas into your company. You can do that by increasing the diversity in the background and experience of the people you hire or by partnering with companies who have creative or technological resources that your organization lacks.

For example, much was made of Apple’s hires in preparation for the launch of the Apple Watch. The CEO of fashion house Yves Saint Laurent joined Apple in 2013, and Apple stores have been seeking retail candidates with “a fashion or luxury background.”5 But even before then, with the appointment of Angela Ahrendts from fashion retailer Burberry to head Apple Retail, the signals were clear that Apple saw an impending fusion of fashion and technology with the advent of wearable technology, and was gearing up.

If companies think of themselves as an island rather than part of an ecosystem (through partnerships whether formal or informal), it can be very hard to drive innovation and new ideas. John Geraci clarified the issue when he described his experience as director of new products at the New York Times from 2013 to 2015. His job was to lead a team in the creation, launch, and development of a new, revenue-driving product that would help restore growth to the company’s bottom line. In a 2016 Harvard Business Review article, Geraci wrote that “it was big, heady stuff” but also “a resounding failure.”6

In Geraci’s first year, the NYT focused on finding entrepreneurial employees, bringing in the right DNA. In the second year, when it became apparent that the new products were not going to hit their targets, the paper shifted its focus and created a special executive board that was supposed to implement a venture capitalist mindset to evaluate new initiatives. But this too didn’t work. Why? Because there wasn’t enough infusion of outside thinking. Geraci describes the NYT as an “organism” with a “wholly internal engine.” For example, NYT employees stay in for lunch and meetings because their “network is inside the building.”

Geraci says this internally focused business model worked for our predecessors. “But in today’s world, it doesn’t. Companies with the organism mindset are too slow to adapt to survive in the modern world. The world around them changes, recombines, evolves, and they are stuck with their same old DNA, their same old problems, their same old (failed) attempts at solutions.”

The alternative is what he calls an ecosystem mindset, where organizations realize they are part of a wider ecosystem. He has seen this mindset in almost all startups but no larger companies. The goal, then, is to make better connections with your ecosystem. How? Geraci’s advice: “Open the doors. Let the light stream in. Get out of the building. Interact. Not just the strategy team, not just the CEO, but everyone. The new value is not inside, it’s out there, at the edges of the network” [emphasis ours].

Publish the Problem

In a period of combinatorial innovation, you are accepting that new ideas for old problems may come from unexpected places. But that only happens when people know what the problem is you’re trying to solve. In the words attributed to Sun Microsystems cofounder Bill Joy, “No matter who you are, most of the smartest people work for someone else.” Two external options involve leveraging the crowd:

![]() Crowdsourcing means publishing a description of the problem in forums available to a large number of people. This technique gives you the chance to tap into a vast network of talent and ideas, but is most applicable for consumer products since that by definition is the makeup of the crowd. However, the underlying notion of crowdsourcing—sharing your problems with strangers—remains uncomfortable for most managers. In a Harvard Business Review article on the topic, the author commented that “Pushing problems out to a vast group of strangers seems risky and even unnatural, particularly to organizations built on internal innovation.” Which is why “Despite a growing list of success stories, only a few companies use crowds effectively—or much at all.”7

Crowdsourcing means publishing a description of the problem in forums available to a large number of people. This technique gives you the chance to tap into a vast network of talent and ideas, but is most applicable for consumer products since that by definition is the makeup of the crowd. However, the underlying notion of crowdsourcing—sharing your problems with strangers—remains uncomfortable for most managers. In a Harvard Business Review article on the topic, the author commented that “Pushing problems out to a vast group of strangers seems risky and even unnatural, particularly to organizations built on internal innovation.” Which is why “Despite a growing list of success stories, only a few companies use crowds effectively—or much at all.”7

![]() Crowd contests—where you offer an incentive or prize for the best option submitted for solving a challenge—are a different beast than crowdsourcing. They tend to attract well-funded teams that can afford to pursue moon-shot ideas. They actually have a long history (e.g., the Longitude Prize, as discussed in Chapter 6). But today’s technology means that crowd contests are both viable and often the preferred option,8 particularly for issues where you don’t know which approach or technology will offer the best solution. And while not suited for every challenge, and bringing with it its own management challenges, the crowd that competes in a contest brings a quantity and diversity of minds that simply cannot be matched internally.

Crowd contests—where you offer an incentive or prize for the best option submitted for solving a challenge—are a different beast than crowdsourcing. They tend to attract well-funded teams that can afford to pursue moon-shot ideas. They actually have a long history (e.g., the Longitude Prize, as discussed in Chapter 6). But today’s technology means that crowd contests are both viable and often the preferred option,8 particularly for issues where you don’t know which approach or technology will offer the best solution. And while not suited for every challenge, and bringing with it its own management challenges, the crowd that competes in a contest brings a quantity and diversity of minds that simply cannot be matched internally.

Element #2: Invent New Business Models, Not Just Products or Services

In the past decade, companies have focused so much on improving their ability to churn out new products and services that it can be disconcerting to think that sources of new growth lie elsewhere. Many companies see continual product introduction as a key driver of business success, and some, such as 3M, make it a priority and key metric. (3M tracks this through its New Product Vitality Index, which measures the percentage of revenue in any one year coming from products created in the last five years; 3M NPVI tops 30 percent.)9

All this activity, however, perhaps obscures the fact that launching exciting new products is rarely enough to sustain margins, especially since the price advantage of new products is quickly eroded by copycats. Apple is probably the best-known example of the alternative. The company continues to build momentum, despite the rapid general commoditization of smartphone features because Apple didn’t just invent a new suite of products, it invented a new business model. This disruptive business model has changed, among other things, how music is sold and consumed (for example, single tracks vs. entire albums), how photos are taken, and how people connect with the world.

A disruptive business model is simply an integrated set of processes and resources to create value for a customer in new and unique ways. Clayton Christensen suggests this means focusing on areas where barriers prevented people from getting particular jobs done—insufficient wealth, access, skill, or time—and there is higher potential for such disruption in industries “where companies focus on products or customer segments, which leads them to refine existing products more and more, increasing commoditization over time.”10

Looking at new business models is a much-discussed but underutilized lever for innovation, and one that can open up new growth opportunities. In a recent survey, “breakthrough innovators” were nearly twice as likely to innovate new business models as other “strong” innovators.11

Zipcar is an example of a disruptive business model, pioneering the concept of car sharing. The company, leveraging phone-enabled technology for reservations and digital keycard systems to unlock cars, solved a specific challenge for the untapped market of young urban consumers: access to automobiles without the headaches and cost of ownership. Zipcar’s approach offers a counterpoint to the traditional rental car companies—focusing on different customers (young urbanites or “Zipsters” versus business travelers), leveraging technology for convenience (access to cars via iPhones and keycards versus rental car counters), offering more granular units of consumption (you can rent by the hour versus 24-hour increments), and with different inventory (Toyota Prius and MINI Cooper versus Chevrolet Malibu and Toyota Corolla). Ultimately it changed the rental car industry. Avis acquired Zipcar in 2013 and rivals Enterprise and Hertz are following similar strategies.

Element #3: Use Experimentation to More Rapidly Find Winners

According to Harrah’s CEO Gary Loveman, there exists a “romantic appreciation for instinct.”

He said, “What I found in our industry was that the institutionalization of instinct was a source of many of its problems” [emphasis ours].13 In other words, gut instinct is not a very effective guide to portfolio expansion opportunities in the Age of Complexity.

The best way to correct instinctual bias is through testing and experimentation. If the “romantic appreciation” endures, it does so more as a source of comfort than a source of utility. The sea of combinatorial possibilities is so vast that predicting the big winners in advance is close to impossible. Thus if we accept the notion that a greater portion of future revenues will come from new rather than incumbent businesses, and recognize that we are prone to viewing new businesses with rose-tinted glasses (that is, unreliably), then it is critical to inject data and testing into the mix. Don’t just look in the mirror, step on the scale. That means building a system for learning and testing: an experimentation machine.

Becoming an Experimentation Machine

Intuit co-founder and chairman Scott Cook sees experimentation less as a choice than as a requirement in order to adapt to the new environment. Cook tells how he always assumed that as a company grew, the quality of decision making would improve. But at Intuit, he says, he noticed it wasn’t improving. He began to worry: “Are some of the things we’re doing unknowable? Is it not possible to predict consumer behavior?”

His personal epiphany about testing came in response to studying and comparing Toyota, Yahoo, and Google. He discovered, for example, that Toyota operates as a “massive series of experiments” throughout the organizational hierarchy. He also talked to Yahoo employees, who told him that Google beat them by running 3,000 to 5,000 experiments a year, trying new things “at a ferocious rate.” The Yahoo-ians told him, “They just outran us. We tried management . . . but we didn’t have that experimentation engine.”

This led Cook to make Intuit into a “testing” culture. Testing cultures have a number of benefits:

![]() You can make better decisions because you’re looking at real consumers and real outcomes, not just theory.

You can make better decisions because you’re looking at real consumers and real outcomes, not just theory.

![]() It neutralizes hierarchy, which means that you enable your most junior people to test their best ideas, and provides a means to avoid having majority rule crush creativity.

It neutralizes hierarchy, which means that you enable your most junior people to test their best ideas, and provides a means to avoid having majority rule crush creativity.

![]() You get surprised more often. As Cook writes, “You only get a surprise when you are trying something and the result is different than you expected, so the sooner you run the experiment, the sooner you are likely to find a surprise, and the surprise is the market speaking to you, telling you something you didn’t know. Several of our businesses here came out of surprises.”

You get surprised more often. As Cook writes, “You only get a surprise when you are trying something and the result is different than you expected, so the sooner you run the experiment, the sooner you are likely to find a surprise, and the surprise is the market speaking to you, telling you something you didn’t know. Several of our businesses here came out of surprises.”

Bart Becht, who ran multinational consumer goods company Reckitt Benckiser for many years, believed in using testing to nurture ideas where people demonstrated ownership and excitement, even if the idea went against the grain.

As an example, he cited a huge internal debate over the merits of a product called Air Wick Freshmatic, which automatically releases freshener into the air on a schedule. The idea originated when one of the Korean brand managers saw a new kind of dispenser in stores there and believed it held some promise for Reckitt Benckiser. So he brought the idea to a meeting at headquarters. According to Becht there was strong disagreement over whether and where (meaning in what markets) such a product could work. The argument against the idea was that it was a completely new type of product for the company and would require new manufacturing facilities.

However, two people saw potential and were willing to fight for it, which was sufficient for Becht to approve testing (on a small scale). Testing launched in the United Kingdom, was a huge hit, and by the end of the year the product was in more than 30 countries.

All of which is to say that the first prerequisite for building an experimentation machine inside your business is an experimentation mindset: a recognition that senior management doesn’t have a monopoly on good ideas, that it is increasingly hard to predict customer behavior, and that testing can both be a source of surprises and a correction to bias.

To do this right, here are some key factors to consider:

![]() Know when you’re experimenting and when you’re not. If you mistake an experiment for a business launch, you may invest too much or go too long before pulling the plug. In The Science of Success, Charles Koch, CEO of Koch Industries, writes that its businesses have certainly suffered “when we forgot we were experimenting and made bets as if we knew what we were doing.” He describes the company’s decision in the early 1970s to plunge heavily into the trading of petroleum and tankers. It was an experiment, but the company didn’t treat it that way. The result? “When the Arab oil cutback hit in 1973 and 1974, we were caught with positions beyond our capability to handle, leaving us with large losses. That was certainly a great learning experience, but I’m not sure I could stand that much learning again.”

Know when you’re experimenting and when you’re not. If you mistake an experiment for a business launch, you may invest too much or go too long before pulling the plug. In The Science of Success, Charles Koch, CEO of Koch Industries, writes that its businesses have certainly suffered “when we forgot we were experimenting and made bets as if we knew what we were doing.” He describes the company’s decision in the early 1970s to plunge heavily into the trading of petroleum and tankers. It was an experiment, but the company didn’t treat it that way. The result? “When the Arab oil cutback hit in 1973 and 1974, we were caught with positions beyond our capability to handle, leaving us with large losses. That was certainly a great learning experience, but I’m not sure I could stand that much learning again.”

![]() Use the experiment to improve your “assumption-to-knowledge” ratio. Academics Rita Gunther McGrath and Ian MacMillan make the point in their book Discovery-Driven Growth that confirmation bias can undermine new businesses, saying it “leads people to embrace new information that reinforces (confirms) their existing assumptions and to reject information that challenges them. Not so bad in an existing business, where your initial assumptions have a good shot at being on the right track, but dangerous in a new business where you’re not yet clear on what you are doing.” The way we think and make assessments is much more likely to be rooted in the dynamics of our incumbent businesses, while our future depends upon an accurate assessment of the new. If we are trying to improve our assumption-to-knowledge ratio, it is important before we start to state our assumptions. When organizations don’t state their assumptions in advance, they run into two problems: assumptions become converted into facts in people’s minds, and organizations don’t learn as much as they could.

Use the experiment to improve your “assumption-to-knowledge” ratio. Academics Rita Gunther McGrath and Ian MacMillan make the point in their book Discovery-Driven Growth that confirmation bias can undermine new businesses, saying it “leads people to embrace new information that reinforces (confirms) their existing assumptions and to reject information that challenges them. Not so bad in an existing business, where your initial assumptions have a good shot at being on the right track, but dangerous in a new business where you’re not yet clear on what you are doing.” The way we think and make assessments is much more likely to be rooted in the dynamics of our incumbent businesses, while our future depends upon an accurate assessment of the new. If we are trying to improve our assumption-to-knowledge ratio, it is important before we start to state our assumptions. When organizations don’t state their assumptions in advance, they run into two problems: assumptions become converted into facts in people’s minds, and organizations don’t learn as much as they could.

![]() Set up metrics to help constantly refine your experimentation capabilities. Think of it as a key metric for the Age of Complexity: the number of “at bats” you have, the number of times you get to test, tinker, and engage with customers. As Amazon’s Jeff Bezos believes, if you double the number of experiments, you double your chances of discovering new innovations. Google’s Schmidt is even more specific: “Our goal is to have more at-bats per unit of time and effort than anyone else in the world.” Part of the rationale for this is that while experimentation is more likely to get you to new customer-relevant ideas faster than ivory tower planning, the odds are still low. That is, you need to do a lot of experiments. Therefore it becomes a numbers game. Which is why companies like Google, Intuit, and Amazon talk in terms of efficiency metrics and work to improve the processes and systems of testing in terms of speed, cost, and rate of learning.

Set up metrics to help constantly refine your experimentation capabilities. Think of it as a key metric for the Age of Complexity: the number of “at bats” you have, the number of times you get to test, tinker, and engage with customers. As Amazon’s Jeff Bezos believes, if you double the number of experiments, you double your chances of discovering new innovations. Google’s Schmidt is even more specific: “Our goal is to have more at-bats per unit of time and effort than anyone else in the world.” Part of the rationale for this is that while experimentation is more likely to get you to new customer-relevant ideas faster than ivory tower planning, the odds are still low. That is, you need to do a lot of experiments. Therefore it becomes a numbers game. Which is why companies like Google, Intuit, and Amazon talk in terms of efficiency metrics and work to improve the processes and systems of testing in terms of speed, cost, and rate of learning.

![]() Suspend what’s not working. Tied to “at bats” but worthy of focus in its own right, the Achilles heel of many experiments is that they linger too long. Everybody loves to start things, but nobody likes to stop things. We become disinterested and disconnected from things that aren’t working. Corporate incentives tend to discourage the declaration of failures. Or, we remain overly optimistic that, given a bit more time and another round of funding, this experiment or venture will turn around. The failure to stop what isn’t working has to change. As evidence: One of Steve Jobs’ first actions when he rejoined Apple in 1997 was to kill the Newton, an early personal digital assistant. He writes that by shutting it down, he freed up engineers who could then work on new mobile devices.14

Suspend what’s not working. Tied to “at bats” but worthy of focus in its own right, the Achilles heel of many experiments is that they linger too long. Everybody loves to start things, but nobody likes to stop things. We become disinterested and disconnected from things that aren’t working. Corporate incentives tend to discourage the declaration of failures. Or, we remain overly optimistic that, given a bit more time and another round of funding, this experiment or venture will turn around. The failure to stop what isn’t working has to change. As evidence: One of Steve Jobs’ first actions when he rejoined Apple in 1997 was to kill the Newton, an early personal digital assistant. He writes that by shutting it down, he freed up engineers who could then work on new mobile devices.14

The side benefit of developing this discipline is the spotlight it puts on the differences between operating the current business and developing the new business, and as a result a more realistic view emerges of what it will take to succeed with the new business.

Making Yourself Less Vulnerable to Attack

Two key challenges define ideation and innovation in today’s world. This chapter has been about the first challenge: improving the odds of finding the next big idea. This requires new mindsets and structures so you can quickly and easily find and take advantage of the ideas no matter where they originate. This focus, by definition, anchors organizations in the reality of customer feedback and helps ward off internal bias. It leads you toward an experimentation mindset, which usually creates greater clarity of vision. Companies operating with a focus on discovery and experimentation “realize sooner that their core positions are facing the threat of erosion,” say McGrath and MacMillan.16

The other key challenge—making sufficient room in an organization for new ideas and dismantling the old—is the focus of our next chapter.