CHAPTER 6

Explorers and Navigators

“Fear and discomfort are an essential part of strategy making.”

—ROGER L. MARTIN

With some notable exceptions, few executives would comfortably embrace the title of Explorer.*

For one, the word exploration still conjures up romantic notions and legendary figures from the nineteenth century and earlier, which may seem distant from today’s everyday realities. Secondly, even a light dusting of these same figures reveals deeply flawed individuals who, while driven to extraordinary achievements, would not today be held up as model citizens. For example, Henry Morton Stanley, of “Dr. Livingstone, I presume” fame, was at one time associated with King Leopold II’s brutal Congolese empire,1 and considered by some to be the inspiration for Marlow, the complex protagonist in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.2 Indeed, what motivated these individuals was a mixed bag, ranging from the conquistador’s search for the “cities of gold” to the more enlightened thirst for knowledge personified by James Cook, who in three epic voyages discovered more of the earth’s surface than any other man.3

These are different times today, to be sure, but if you can make the mental leap from one context to another, we think there’s no better term for distilling some of the critical qualities at the heart of leadership in a complex world: willingness to lead despite incomplete information, boldness, determined focus, and adaptability.

Moreover, we like the term explorer as it conveys a certain level of natural risk—one cannot discover new lands without taking chances—thereby putting a bright light on some of the harder truths that can get obscured over time about achieving profitable growth in a large organization. It is not a straightforward process, and there are no guarantees. Rather, it requires an explorer’s sense of boldness and ambition, guided by strong navigational skills, to stay off the rocks.

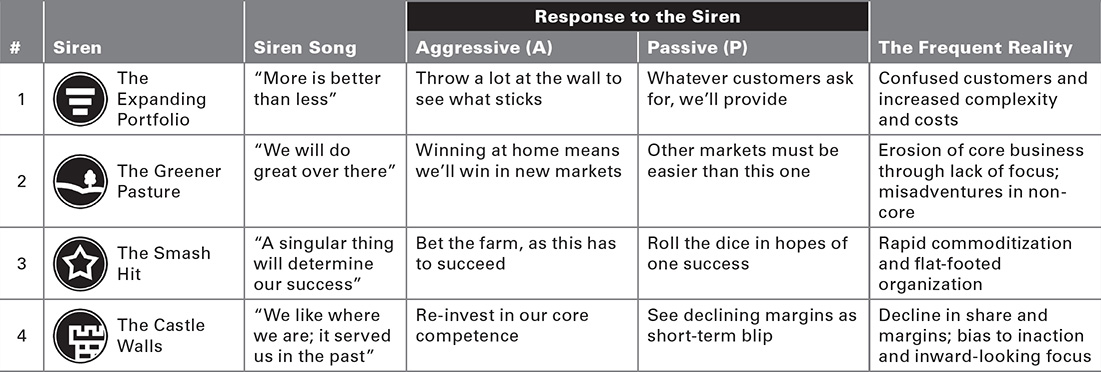

Lack of navigational skills is evident in many of the Sirens stories from Chapter 4. Consider the story of Rubbermaid, where the strategy was clear, as shown by CEO Schmitt’s statement, “Our objective is to bury competitors with such a profusion of products that they can’t copy us.”4 But what was lacking was an understanding of the impact of proliferation on service levels and cost structure.

Before the discovery of a practical means for determining longitude, successful exploration was frequently a happy accident, the result of good luck, despite great seamanship and the best charts available. The lack of a reliable means of navigation led to many shipwrecks and the loss of life in the process. In fact, when the British government passed the Longitude Act of 1714, laying out a prize for anyone who could come up with a “Practicable and Useful” method for determining longitude at sea, it was largely in response to a disaster in 1707 off the Isles of Scilly in which four homebound British warships under the command of Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell became lost in the fog, disoriented, and believed themselves to be off the northwest coast of France. In fact, the ships were sailing just off the Isles of Scilly on the southwest tip of England. The ships crashed and sank, killing 2,000 sailors. It was also a reflection of the current belief that whichever nation could crack the code of determining longitude would control the seas and become the dominant economic global power.5

Before John Harrison’s clock-based method for determining longitude became commonplace, sailors used crude navigational techniques such as “dead reckoning” to assess longitude. “The captain would throw a log overboard and observe how quickly the ship receded from this temporary guidepost.”6 Not surprisingly, they frequently missed their mark, missing land entirely and spending more time at sea. More time at sea with no fresh fruit meant scurvy, a dreadful and deadly disease caused by vitamin C deficiency. Forced to navigate by latitude alone, most followed well-trafficked routes, or hugged coastlines where they could. The resulting traffic jam left ships vulnerable to piracy.

Piracy, scurvy, shipwrecks: thankfully not issues usually on a CEO’s agenda! But these were considered the cost of doing business as a merchant ship in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, before better navigational tools changed the game, a parallel with the opportunity companies have today in building new capabilities for finding scale and profitable growth.

The Explorer’s Mindset

Scurvy may be long gone, but the challenges facing leaders are no less daunting.

In an interview with the Guardian newspaper,7 Unilever CEO Paul Polman said, “These are very difficult times; it’s very uncertain going forward. You get currencies that go up and down 20 percent, you get markets that shift very rapidly. So you need to have people who can feel comfortable dealing with a VUCA world—volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous.”

Even putting aside the considerable uncertainties in markets, leaders face many new challenges in their day-to-day activities:

1. Excessive demands on time and focus. With increased complexity, even the most disciplined leaders and organizations are struggling to find sufficient time and management bandwidth to deal effectively with everything on their plate. Productivity is impaired by the multiple “mental changeovers” of multitasking required on a daily basis.

2. An overwhelming (nonlinear) increase in data availability, coupled with an increasing need to make decisions on 80 percent (or less) of the information. As the pace of data creation increases—for example, it is estimated that Walmart collects multiple petabytes8 of data every hour on its customer transactions9—so does the responsibility to make productive use of it. But that requires new strategies and capabilities that are often lacking, creating new management challenges. Moreover, it can lead to a false supposition that all decisions can be definitively addressed through detailed analytics. For many strategic decisions, data can help increase the odds, but at some point represents simply hesitation. It is a great paradox that just as the amount of information increases, so does the need to make decisions with an 80 percent confidence level (or lower) as the importance for earlier decisions increases.

3. Given the above, a greater difficulty separating out truly critical from just important. A competitor launches a new product category; operational issues arise; a strategy colleague proposes a further expansion overseas; every week detailed reports land on your desk: Where do you focus your time? It is not uncommon for leaders to be inundated with information, ideas, and requests. Schedules are frequently booked up two months in advance. Given this level of absorption by the business, it can be increasingly difficult to retain perspective, to pull up to understand what is truly critical to the business.10

These are new dynamics that have significantly complicated the leader’s task over the last decade. As a result, some companies are losing sight of the elements that propelled them forward in the beginning: a deep focus on the customer, a compelling vision and offer, and willingness to adapt and learn.

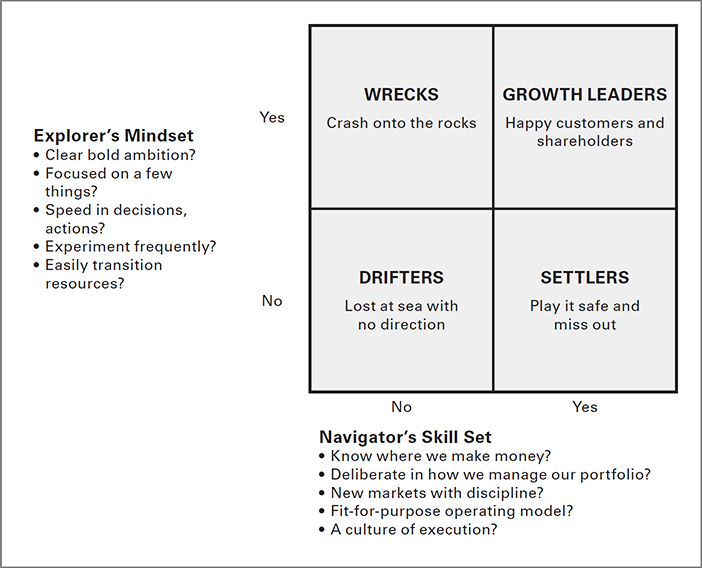

The antidote to these challenges is the right leadership outlook that can help restore focus on serving the customer and finding a source of differentiation. In our work with clients, we have identified five key leadership components that separate those who are able to cut through complexity and find growth from those who tend to drift in its current. We’ve captured the Explorer’s Mindset in the five statements below. Read through them and think about how true they are for your organization.

EXPLORER’S MINDSET

1. Our strategy is bold and reflects our distinctive beliefs.

2. We are ruthlessly focused on a few things.

3. Speed is built into everything we do.

4. We experiment frequently to improve the odds.

5. We easily transition in and out of new opportunities, products, and markets and shift around resources correspondingly.

How did you do? If you shared these with colleagues, would there be strong agreement, or would an energetic discussion ensue? What matters is not precision, but rather frankness in your assessment of how your organization stacks up against these statements. (A client once told us that they were a “reality-based organization,” an aspiration we’d endorse.) If these statements do not describe your current organization, don’t worry. In Part III of the book, you’ll find ideas and resources to help you close the gap.

The Navigator’s Skill Set

The second dimension is what we call the Navigator’s Skill Set: the set of new capabilities critical to navigating our new complex environment. In some cases, these are skills such as New Market Entry that require some adaptation to account for today’s conditions. In other cases, we identify new capabilities (such as Square-Root Costing) to accurately understand where you’re making money in your organization. We’ve captured below the five skills that comprise the Navigator’s Skill Set. Once again, read through and consider how close your organization reflects the statements:

NAVIGATOR’S SKILLSET

1. We know where we really make money.

2. We are deliberate in how we manage our portfolio.

3. We approach new markets and targets with discipline.

4. Our operating model is fit-for-purpose.

5. We execute efficiently and consistently.

Again, how did you do? Which represent the biggest gaps? In Part IV, we will discuss ways to bolster each of these.

To underscore the importance of these capabilities, consider what happens if an organization has a strong Explorer’s Mindset yet is deficient in the Navigator’s Skill Set. When Ron Johnson came in as new CEO of JC Penney in the fall of 2011, the move was widely lauded as just what the ailing department store chain needed. Johnson had a stellar track record and was considered one of the most accomplished merchandisers and retailers of his time. In the 1990s, he orchestrated the transformation of Target into a modern retailer.11 He then went on to collaborate with Steve Jobs on the creation of the Apple Store, introducing defining elements such as the Genius Bar, and in the process building what was to become the company’s primary point of connecting with customers, as well as developing Apple into the most profitable retailer in the United States.12 So when he joined JC Penney, he was viewed as something of a savior. Certainly, the retail chain needed something of a miracle. It had suffered years of underperformance, with a tired, dowdy image and cluttered stores:

While Johnson spent several months deliberating J.C. Penney’s transformation, the executive team toured company stores and warehouses, finding dusty, excess inventory and crowded, outdated sales floors. They also criticized the inefficiency of J.C. Penney’s corporate headquarters in Plano: according to one report, during January 2012, a staff of 4,800 watched 5 million YouTube videos during work hours. [Incoming COO Michael] Kramer recalled how he felt about the company’s culture when he first joined: “I hated the company culture. It was pathetic.”13

Just 17 months later, Johnson was fired by the board. He had indeed taken bold action. “Penney’s had been run into a ditch when he took it over. But, rather than getting it back on the road, he’s essentially set it on fire,” said Mark Cohen, a former CEO of Sears Canada.14 The bold action had alienated its core customers, and shareholders witnessed a catastrophic drop in share price. It is too easy to armchair-diagnose the situation after the fact. But even at the time, many saw his key transformational initiatives as being risky:

The new pricing strategy is ambitious—and risky. Customers have been trained by Penney’s and others to hold out for massive discounts. In the era of online shopping, few have the inclination to visit a store with a faded brand like J.C. Penney’s. Johnson knows all of that and seems to relish the challenge.15

In fact, much of the value he brought to JC Penney would have been enhanced by the disciplines inherent in the Navigator’s Skill Set: His focus on instinct and experience was helpful in setting a vision, but leveraging the data on what shoppers wanted would have focused this. His disregard for testing was something he picked up from Steve Jobs, and perhaps an asset in the context of creating a new entity such as the Apple Store, but catastrophic in this case, as he refused to test the impact of a new pricing strategy. His vision for the stores was distinct, but the operating model for the build-out of custom shops was rife with complexity: with unique fixtures and merchandise, with different footprints within thousands of stores, with construction by different contractor teams, the odds were always stacked against this being accomplished in a cost-effective manner. A consideration of scale would have been helpful. And his general lack of feel for JC Penney’s core customers was the unintended consequence of a desire by Johnson and the board to broaden the appeal to include a younger demographic, but ended up, as Johnson later admitted, insulting the core customer.16

Identify Your Starting Point

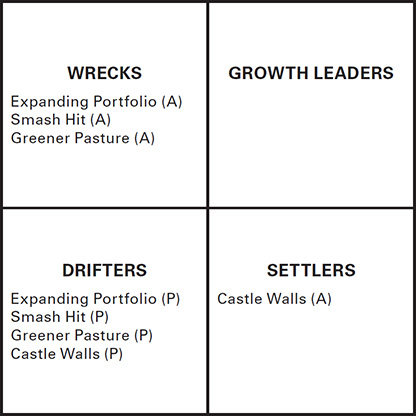

Thus far we have shared 10 statements. The degree to which you recognize your organization in them—or do not—may indicate the degree to which you are vulnerable to the Sirens, and will start to illuminate the shifts required, either in mindset or capability, in order to find growth in a complex world. This is summarized on the two-by-two chart in Figure 6.1, the Explorer-Navigator Matrix. Every CEO, COO, and corporate leader needs to determine their starting point, where their company sits in the matrix. If you are still not sure, here are profiles for each quadrant:

FIGURE 6.1: The Explorer-Navigator Matrix

![]() Drifters. These companies lack both the bold leadership of Explorers and the solid executional strengths of Navigators. Because they lack clear strategic direction, Drifters are stuck with lackluster operational and innovation capabilities. They therefore drift in the marketplace and suffer market share loss and profit erosion. This year doesn’t look much different for them than last year. These companies are often defined by slow decision making, organizational inertia, and silos, as individual leaders vie for fiefdoms in different parts of the business. How quickly they decline will depend on the strengths and speed of their competition. If your business is drifting, then you will need to embark on a journey that pulls on elements described in both Parts III and IV, defining your level of ambition and focus, and shoring up capabilities to execute on this.

Drifters. These companies lack both the bold leadership of Explorers and the solid executional strengths of Navigators. Because they lack clear strategic direction, Drifters are stuck with lackluster operational and innovation capabilities. They therefore drift in the marketplace and suffer market share loss and profit erosion. This year doesn’t look much different for them than last year. These companies are often defined by slow decision making, organizational inertia, and silos, as individual leaders vie for fiefdoms in different parts of the business. How quickly they decline will depend on the strengths and speed of their competition. If your business is drifting, then you will need to embark on a journey that pulls on elements described in both Parts III and IV, defining your level of ambition and focus, and shoring up capabilities to execute on this.

![]() Settlers. These organizations lack the boldness of Explorers and so rely completely on their Navigation skills. They function efficiently but are late to the party. With many strong operational and financial capabilities, these companies may even describe their strategy as that of a “fast follower.” But that can lead to a tendency to diffuse energy over too many initiatives, become reactive and avoid making true strategic trade-offs. As life cycles shorten, Settlers become more vulnerable. If you fall into this category, the opportunity is in injecting true strategic direction and focus to marshal resources to a point of market leadership (as discussed in Part III).

Settlers. These organizations lack the boldness of Explorers and so rely completely on their Navigation skills. They function efficiently but are late to the party. With many strong operational and financial capabilities, these companies may even describe their strategy as that of a “fast follower.” But that can lead to a tendency to diffuse energy over too many initiatives, become reactive and avoid making true strategic trade-offs. As life cycles shorten, Settlers become more vulnerable. If you fall into this category, the opportunity is in injecting true strategic direction and focus to marshal resources to a point of market leadership (as discussed in Part III).

![]() Wrecks. This is what happens to Explorers who lack Navigator skills! Often energized by a bold strategy (and one frequently driven by individual conviction), companies in this quadrant are nonetheless vulnerable to giant missteps and may crash on the rocks. Absent organizational discipline and a focus on the drivers of customer value, these organizations may convert boldness to ill-fated acquisitions, market expansions, or discontinuous strategies. If your business is trending this way, then you will gain enormous value from adding the disciplines described in Part IV: in essence, ensuring that your current levels of ambition and energy yield outcomes that your customers actually value, that they will pay for, and that you can deliver.

Wrecks. This is what happens to Explorers who lack Navigator skills! Often energized by a bold strategy (and one frequently driven by individual conviction), companies in this quadrant are nonetheless vulnerable to giant missteps and may crash on the rocks. Absent organizational discipline and a focus on the drivers of customer value, these organizations may convert boldness to ill-fated acquisitions, market expansions, or discontinuous strategies. If your business is trending this way, then you will gain enormous value from adding the disciplines described in Part IV: in essence, ensuring that your current levels of ambition and energy yield outcomes that your customers actually value, that they will pay for, and that you can deliver.

![]() Growth Leaders. Companies in this quadrant combine the strengths of Explorers and Navigators. They focus resources on areas where there is a good chance of winning and creating scale in their businesses. Growth Leaders have a clear and bold strategy that stretches the business and, in so doing, provides a sense of mission and urgency. These organizations are characterized by coherence and deliberateness. They have a culture of execution, discipline in market expansion, and an informed view of how and where they make money.

Growth Leaders. Companies in this quadrant combine the strengths of Explorers and Navigators. They focus resources on areas where there is a good chance of winning and creating scale in their businesses. Growth Leaders have a clear and bold strategy that stretches the business and, in so doing, provides a sense of mission and urgency. These organizations are characterized by coherence and deliberateness. They have a culture of execution, discipline in market expansion, and an informed view of how and where they make money.

Become a Growth Leader—Again!

As you consider which quadrant best describes your current situation—and assuming you’re among the many who can relate to Drifters, Settlers, or Wrecks—you may wonder, How did we get here?

The fact is, many organizations are launched on the back of innovative products that addressed customers’ needs in new and different ways, or similarly disrupted the markets, and yielded great financial success. In other words, most began as Growth Leaders, albeit at a much smaller revenue base, before the quest for growth ultimately undermined that which made them successful in the first place. This is helpful to understand as a motivator, as the goal is much more around rediscovering something that once defined you, rather than finding greatness for the first time.

When a company loses focus—often in the pursuit of growth and scale—it tends to drift. Corporate leaders, who previously were primarily focused on serving the customers, now find their calendars brimful with meetings on operational issues, firefighting, and people issues. It’s a central irony that a lot of the challenges we are highlighting in this book arise in the name of serving the customer (more choice, more options, and so on), yet one of the biggest side-effects is often a loss of customer focus.

Therefore, in order to regain status as a Growth Leader, it is the leader’s job in particular to recapture and embody the qualities that underpin the Explorer’s Mindset—boldness, focus, speed, experimentation, and reinvention—as doing so will return the business to an external customer focus. It is critical to assess frankly your organizational capabilities (Navigator’s Skill Set), as absent an accurate audit, a business is likely to fall further prey to the Sirens.

The rest of this book is designed to help you reinvigorate the mindset and skill set required to close your gaps, as a counterpoint to the slow atrophy and internal focus that can creep into large businesses over time. We wish you fair winds and following seas!

CALL TO ACTION

CALL TO ACTION

Assess Your Strategy and Set a Course

Opportunity:

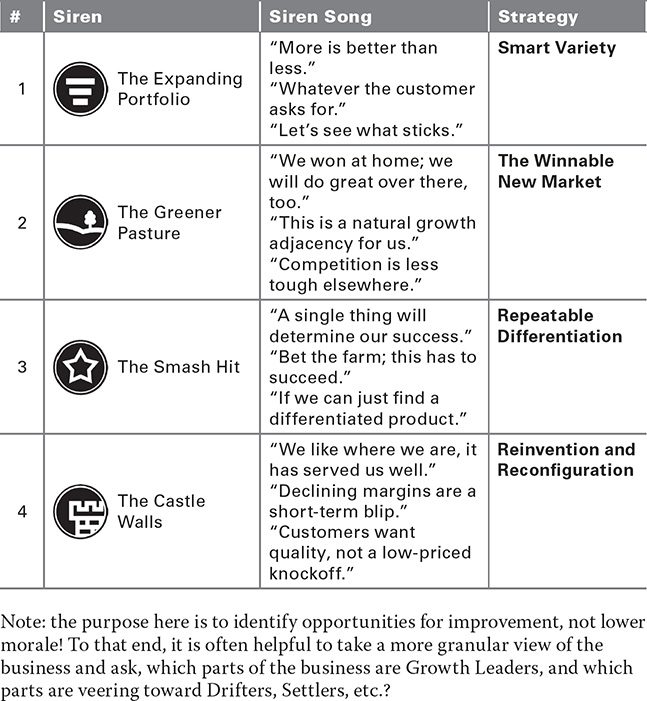

You have now met the Sirens, and seen how some organizations adapt their strategies and build organizational capabilities to resist the Siren Song and achieve profitable growth. What dangers do you see? Which Sirens do you see as potentially steering you off track? The first step is to assess your strategy to ensure your business is not in danger of being lured in by a Siren Song.

Key questions for discussion:

![]() Which Siren(s) is your business susceptible to?

Which Siren(s) is your business susceptible to?

![]() What are the implications for your business if you fall prey to the Siren(s)?

What are the implications for your business if you fall prey to the Siren(s)?

![]() How can you adapt your current path to resist the Siren Song?

How can you adapt your current path to resist the Siren Song?

Areas to investigate:

![]() Assess your strategy to identify which, if any, Sirens are present.

Assess your strategy to identify which, if any, Sirens are present.

![]() Assess what it would take to navigate to a better outcome, e.g., Smart Variety vs. the Expanding Portfolio.

Assess what it would take to navigate to a better outcome, e.g., Smart Variety vs. the Expanding Portfolio.

![]() Based on initial review of the Explorer’s Mindset and Navigator’s Skill Set, assess whether you most closely resemble a Growth Leader, a Drifter, a Settler, or a Wreck.1

Based on initial review of the Explorer’s Mindset and Navigator’s Skill Set, assess whether you most closely resemble a Growth Leader, a Drifter, a Settler, or a Wreck.1

![]() Based on this, identify priorities for further analysis and improvement.

Based on this, identify priorities for further analysis and improvement.

* Messrs. Bezos, Branson, and Musk come to mind: each pursuing a space venture (Blue Origin, Virgin Galactic, and SpaceX, respectively).