CHAPTER 6

Have a Productive Conversation

You’re now ready to have a constructive discussion. Your goal is to work with your counterpart to better understand “the underlying causes of the problem and what you can do to solve it together,” says Jeanne Brett.

First, frame the discussion so that you and your counterpart start off on the right foot. Then there are three things you’ll do simultaneously as the conversation flows: Manage your emotions, listen well, and be heard.

When you sit down with your counterpart, don’t be overly wedded to the information you’ve gathered in advance. Be flexible. “You don’t want to be so prepared that you anticipate a particular reaction and you’re not able to take in what’s actually happening,” says Amy Jen Su. If you see the behavior you expected, then label it (in your head) and continue to observe. But allow yourself to be surprised, too. The same goes for cultural norms. “Knowing something about your colleague’s culture gives you hypotheses to test. But just because you have an East Asian at the table doesn’t mean he will be indirect,” says Brett.

Frame the Conversation

Your first few sentences can make or break the rest of the discussion. Set the conversation up for success by establishing common ground between you and your counterpart, labeling the type of conflict you’re having, asking your counterpart for advice, laying out ground rules, and focusing on the future. Here’s more on how to do that.

Focus on common ground

“Too often we end up framing a conflict as who’s right or who’s wrong,” Linda Hill says. Instead of trying to understand what’s really happening in a disagreement, we advocate for our position. Hill admits that it’s normal to be defensive and even to blame the other person, but implying “You’re wrong” will make matters worse. Instead, state what you agree on. In chapter 4, when you identified the type of conflict you’re having, you noted where there was common ground, and in chapter 5, you identified where your goals might overlap. Put those commonalities out there as a way to connect. “We both want to make sure our patients get the best care possible” or “We agree that the new email system should integrate with our existing IT systems” or “We both want our department to get adequate funding.”

If you weren’t able to pinpoint something that you both agreed on beforehand or you’re not sure you know what your counterpart’s goal is, the easiest way to find out is to ask, says Jonathan Hughes, “although sometimes people need help crystallizing their goals.” Explain what’s important to you and then ask, “Is there any overlap with what you care about? Or do you have another goal?” Asking questions like these sets a collaborative tone.

Label the type of conflict

Acknowledge the type of conflict you’re having—relationship, task, process, or status—and check with your counterpart that he sees it the same way. “It seems as if the crux of our disagreement is about where to launch the product first. Do you agree?” You may also want to reassure him that you value your relationship. This will convey to him that your point of contention is not a personal one. Say something like, “I really respect you and how you run your department. This is not about our relationship, but about how our two teams will work together on this project.”

If your conflict covers several different types, as many do, name each one in turn so that they’re all out on the table. Hughes suggests you say something along these lines: It feels like we agree on the same goal here—to bring in revenue from this new product as soon as possible. [Establishing common ground on task] Our conflict seems to be more about how we do it—the timing of how quickly we roll out this product and whether we roll it out in target markets first. [Labeling the process conflict] In addition to that disagreement over the means, it seems—and I could be wrong about this—you feel some frustration with me about how I’ve approached this. [Naming the relationship conflict] I want to put that all on the table because success is going to depend on us working together.

Ask for advice

Research by Katie Liljenquist at Brigham Young University’s Department of Organizational Leadership and Strategy and Adam Galinsky, the chair of the Management Department at the Columbia Business School, has shown that asking for advice makes you appear more warm, humble, and cooperative—all of which can go a long way in resolving a conflict. “Being asked for advice is inherently flattering because it’s an implicit endorsement of our opinions, values, and expertise. Furthermore, it works equally well up and down the hierarchy—subordinates are delighted and empowered by requests for their insights, and superiors appreciate the deference to their authority and experience,” say Liljenquist and Galinsky. Of course, any goodwill garnered by this tactic will swiftly be undone if you ignore your counterpart’s suggestions. Incorporate at least some small part of what she advises into your approach.

There are two other benefits to framing a conflict as a request for advice, according to Liljenquist and Galinsky. First, you nudge your counterpart to see things from your perspective. “The last time someone came to you for advice, most likely, you engaged in an instinctive mental exercise: You tried to put yourself in the other person’s shoes and imagine the world through his eyes,” they explain. The second benefit is that an adversary-turned-advisor may well become a champion for your cause. “When someone offers you advice, it represents an investment of his time and energy. Your request empowers your advisor to make good on his recommendations and become an advocate,” they say.

Set up ground rules

The conversation will go more smoothly if you agree on a code of conduct. At a minimum, suggest no interrupting, no yelling, and no personal attacks. This is especially important for conflict seekers, who may see no problem in raising their voices. Acknowledge that you both may need to take a break at some point. Then ask what other rules are important to your counterpart. If you’re concerned your colleague won’t abide by the rules, write them down on a piece of paper to keep in front of you or on a whiteboard if you’re in a conference room. If your counterpart begins to raise his voice, for example, you can nod toward the written rules and offer a gentle reminder. “We said we weren’t going to yell. Can you lower your voice?” These rules may also be helpful if you need to change the tone of the conversation later on (see “Change the tenor of the conversation” later in the chapter).

Focus on the future

It’s tempting to rehash everything that’s happened up to this point. But it’s generally not helpful to go over every detail or to focus too heavily on the past. “You can’t resolve a battle over a problem that has already happened, but you can set a course going forward,” says Judith White. Focus the discussion on solving the problem and moving on. You can start by saying “I know a lot has gone on between us. If it’s OK with you, I’d like to talk about what we both might do to make sure this project gets completed on budget and how we can better work together in the future.” If your counterpart starts to harp on the past, don’t chastise her for it. Instead, refocus the conversation by saying something like “I hear you. How can we make sure that doesn’t happen again?”

Each of these steps will establish the right tone for your conversation: that you and your counterpart are in it together and you need to reach a resolution that works for both of you.

Manage Your Emotions—and Theirs

Conflict can bring up all sorts of negative emotions for seekers and avoiders alike. Recognize the emotion, but don’t let it stop you from having the conversation. To watch your own reaction while also recognizing your counterpart’s feelings, understand why conflict can feel so bad. Remain calm, acknowledge and label your feelings, and allow for venting. Let’s take a closer look at how to manage emotions and clear the way for a productive discussion.

Understand why you’re so uncomfortable

In the middle of a tough conversation, it can be difficult to take a deep breath and think rationally about what to do next. This is because you’re fighting your body’s natural reaction, says psychiatry professor John Ratey. Your brain experiences conflict, particularly relationship conflict, as a threat: I disagree with you. You haven’t done your job. I don’t like what you just said. You’re wrong. I hate you.

Leadership expert Annie McKee suggests that conflict makes us feel bad because it means we’re going to have to give something up—our point of view, the way we’re used to doing something, or maybe even power. That threat triggers your sympathetic nervous system. As a result, your heart rate and breathing rate spike, your muscles tighten, the blood in your body moves away from your organs. “Some people feel their stomach tense as acid moves into it,” says Ratey.

Depending on the perceived size and intensity of the threat, you may then move into fight-or-flight mode. “When you’re panicking, feeling crushed or overwhelmed, the body’s response is to be aggressive—punch or push back—or to run away and hide,” says Ratey. “This is when you’re in it full-time and the discomfort goes all over your body. It’s like seeing a bunch of snakes or spiders in front of you.” When your brain perceives danger like this, it can be difficult to make rational decisions, which is precisely what you need to do in a difficult conversation. Luckily, it’s possible to interrupt this physical response and restore calm in your body.

Remain calm

There are several things you can do to keep your cool during a conversation or to calm yourself down if you’ve gotten worked up. For conflict seekers, it’s especially important to keep your temper in check. For avoiders, these tactics will help keep you from retreating from the conversation.

- Take a deep breath. Notice the sensation of air coming in and out of your lungs. Feel it pass through your nostrils or down the back of your throat. This will take your attention off the physical signs of panic and keep you centered.

- Focus on your body. “Standing up and walking around may activate the thinking part of your brain,” says Ratey, and keep you from exploding. If you and your counterpart are seated at a table, instead of leaping to your feet, you can say, “I feel like I need to stretch some. Mind if I walk around a bit?” If that doesn’t feel comfortable, do small things like crossing two fingers or placing your feet firmly on the ground and noticing what the floor feels like on the bottom of your shoes.

- Look around the room. Become more aware of the space between you and your counterpart, suggests Jen Su. Notice the color of the walls or any artwork hanging there. Watch the hands of the clock move. “Pay attention to the whole room,” she says. “This will help you realize that there’s more space in the room than you’re currently allowing.”

- Say a mantra. Jen Su also recommends repeating a phrase to yourself to remind you to stay calm. Some of her clients have found “Go to neutral” to be a helpful prompt. You can also try “This isn’t about me,” “This will pass,” or “This is about the business.”

- Take a break. You may need to excuse yourself for a moment—get a cup of coffee or a glass of water, go to the bathroom, or take a brief stroll around the office. If you agreed up front that this might happen, you can say, “I think I need that break now. OK if we come back in five minutes?” If pushing pause wasn’t on your list of ground rules, you can still make the request: “I’m sorry to interrupt you, but I’d love to get a cup of coffee before we continue. Can I get you something while I’m up?”

Acknowledge and label your feelings

When you’re feeling emotional, “the attention you give your thoughts and feelings crowds your mind; there’s no room to examine them,” says Susan David. To get distance from the feeling, label it. “Just as you call a spade a spade, call a thought a thought and an emotion an emotion,” says David. He is so wrong about that and it’s making me mad becomes I’m having the thought that my coworker is wrong, and I’m feeling anger. Labeling like this allows you to see your thoughts and feelings for what they are: “transient sources of data that may or may not prove helpful.” When you put that space between these emotions and you, it’s easier to let them go—and not bury them or let them explode.

Allow for venting

You’re probably not the only one who’s upset. When your counterpart expresses anger or frustration, don’t stop him. Let him vent as much as possible and remain calm while this is happening. Seekers may naturally do this, while you may have to draw an avoider out. If you took the time to air your own feelings with someone else (as discussed at the end of the previous chapter), you’ll understand the importance of giving your counterpart this space. That’s not to say it’s easy. Brett explains:

It’s hard not to yell back when you’re being attacked, but that’s not going to help. To remain calm while your colleague is venting and perhaps even hurling a few insults, visualize your coworker’s words going over your shoulder, not hitting you in the chest. Don’t act aloof; it’s important to indicate that you’re listening. But if you don’t feed your counterpart’s negative emotion with your own, it’s likely he or she will wind down. Without the fuel of your equally strong reaction, he or she will run out of steam.

Don’t interrupt the venting or interject your own commentary. “Hold back and let your counterpart say his or her piece. You don’t have to agree with it, but listen,” Hill says. While you’re doing this, you might be completely quiet or you might indicate you’re listening by using phrases such as “I get that” or “I understand.” Avoid saying anything that assigns feeling or blame, such as “Calm down” or “What you need to understand is . . .” This can be an explosive trigger for a conflict seeker. If you can tolerate the venting, without judging, you’ll soon be able to guide the conversation to a more productive place. Refocus the conversation on the substance of the conflict by saying “I’m glad I got to hear how this has affected you. What do you think we should do next?” This will begin to draw out potential solutions so that you can move toward a resolution.

Listen Well

“If you listen to what the other person is saying, you’re more likely to address the right issues and the conversation always ends up being better,” says Jean-François Manzoni. Hear your counterpart out and ask questions. Here are tips for doing that.

Hear your coworker out

Even if you think you already understand your co worker’s point of view—and you’ve put yourself in her shoes ahead of time—hear what she has to say. This is especially important if you aren’t sure of what the other person sees as the root of the conflict. Acknowledge that you don’t know, and ask. This shows your counterpart “that you care,” Manzoni says. “Express your interest in understanding how the other person feels” and “take time to process the other person’s words and tone,” he adds. Be considerate and show compassion by validating what she’s saying with phrases such as “I get it” or “I hear you.” According to Jeff Weiss, this requires that you “stop figuring out your next line” and actively listen. Your coworker’s explanation of his side may uncover an important piece of information that leads to a resolution. For example, if he says he’s just trying to keep his boss happy, you can help him craft a resolution that addresses his boss’s concerns.

Ask thoughtful questions

It’s better to ask questions than to make statements; questions demonstrate your receptiveness to a genuine dialogue. This is when you bring in the questions you crafted in the previous chapter to unearth your counterpart’s viewpoint and test your hypotheses (see the sidebar “Questions to Draw Out Your Counterpart’s Perspective”). Once you’ve had a chance to hear her thoughts, Hill suggests you paraphrase and ask, “I think you said X. Did I get that right?”

QUESTIONS TO DRAW OUT YOUR COUNTERPART’S PERSPECTIVE

- What about this situation is most troubling to you?

- What’s most important to you?

- Can you tell me about the assumptions you’ve made here?

- Can you help me understand your thinking here?

- What makes you say that?

- Can you tell me more about that?

- What leads you to believe that?

- How does this relate to your other concerns?

- What would it take for us to be able to move forward? How do we get there?

- What would you like to see happen?

- What does a resolution look like for you?

- What ideas do you have that would meet both our needs?

- If this was completely in your control, how would you handle it?

Don’t just take what she says at face value. This is especially important for a conflict avoider, who may not tell you all that she’s thinking. Ask what her viewpoint looks like in action. For example, says team expert Liane Davey, “If you are concerned about a proposed course of action, ask your teammates to think through the impact of implementing their plan. ‘OK, we’re contemplating launching this product only to our U.S. customers. How is that going to land with our two big customers in Latin America?’ This is less aggressive than saying ‘Our Latin American customers will be angry.’” She adds: “Anytime you can demonstrate that you’re open to ideas and curious about the right approach, it will open up the discussion.”

Hill suggests you also get to the underlying reason for the initiative, policy, or approach that you’re disagreeing with. You’ve already labeled the conflict as relationship, task, process, and/or status, but return to those categories in your questions to give your counterpart the opportunity to share her view. How do you see the goal differently? Why do you think you’re the best person to lead the team?

Figure out why your counterpart thinks his idea is a reasonable proposal. Say something like, “Sam, I want to understand what we’re trying to accomplish with this initiative. Can you go back and explain the reasoning behind it?” Get Sam to talk more about what he wants to achieve and why. It’s not enough to know that he wants the project to be done in six months. You need to know why that’s important to him. Is it because he made a promise to his boss? Is it because the team that’s dedicated to the project needs to be freed up to take on an important client initiative? These are his underlying interests, and they’ll help you later when you’re trying to craft a resolution that incorporates his viewpoint (see chapter 7, “Get to a Resolution and Make a Plan”).

You can return to the notion of asking for advice here. Perhaps you genuinely don’t understand something, or you’re shocked by something your counterpart has said. Davey suggests that you be mildly self-deprecating and own the misunderstanding. “If something is really surprising to you (you can’t believe anyone would propose anything so crazy), say so. ‘I think I’m missing something here. Tell me how this will address our sales gap for Q1.’ This will encourage the person to restate his perspective and give you time to understand it.”

Respectfully listening to and acknowledging your counterpart’s viewpoint sets the stage for you to share your side of the conflict. If he feels heard, he’s more likely to hear you out as well.

Be Heard

When it’s time to share your story, allow your counterpart to understand your perspective in a genuine way. “Letting down your guard and letting the other person in may help her understand your point of view,” says Mark Gerzon, author of Leading Through Conflict: How Successful Leaders Transform Differences into Opportunities. Help your coworker see where you’re coming from by speaking from your own perspective, thinking before you talk, and watching body language (yours and hers) for clues that the conversation may be going off the rails.

Own your perspective

If you feel mistreated, you may be tempted to launch into your account of the events: “I want to talk about how horribly you treated me in that meeting.” But that’s unlikely to go over well.

Instead, treat your opinion like what it is: your opinion. Start sentences with “I,” not “you.” Say “I’m annoyed that this project is six months behind schedule,” rather than “You’ve missed every deadline we’ve set.” This will help the other person see your perspective and understand that you’re not trying to blame him.

With a relationship conflict, explain exactly what is bothering you and follow up by identifying what you hope will happen. You might say, “I appreciate your ideas, but I’m finding it hard to hear them because throughout this process, I’ve felt as if you didn’t respect my ideas. That’s my perception. I’m not saying that it’s your intention. I’d like to clear the air so that we can continue to work together to make the project a success.”

Dorie Clark, author of Reinventing You: Define Your Brand, Imagine Your Future, says that you should admit blame when appropriate. “It’s easy to demonize your colleague. But you’re almost certainly contributing to the dynamic in some way, as well,” Clark says. To get anywhere, you have to understand—and acknowledge—your role in the situation. Admitting your faults will help set a tone of accountability for both of you, and your counter part is more likely to own up to her missteps as well. If she doesn’t, and instead seizes on your confession and harps on it—“That’s exactly why we’re in this mess”—let it go. See it as part of the venting process described earlier.

Pay attention to your words

Sometimes, regardless of your good intentions, what you say can further upset your counterpart and make the issue worse. Other times you might say the exact thing that helps the person go from boiling mad to cool as a cucumber. See the sidebar “Phrases to Make Sure You’ve Heard.” There are some basic rules you can follow to keep from pushing your counterpart’s buttons. Of course you should avoid name-calling and finger-pointing. Focus on your perspective, as discussed above, avoiding sentences that start with “you” and could be misinterpreted as accusations. Your language should be “simple, clear, direct, and neutral,” says Holly Weeks. Don’t apologize for your feelings, either. The worst thing you can do “is to ask your counterpart to have sympathy for you,” she says. Don’t say things like “I feel so bad about saying this” or “This is really hard for me to do,” because it takes the focus away from the problem and toward your own neediness. While this can be hard, especially for conflict avoiders, this language can make your counterpart feel obligated to focus on making you feel better before moving on.

PHRASES TO MAKE SURE YOU’RE HEARD

- “Here’s what I’m thinking.”

- “My perspective is based on the following assumptions . . .”

- “I came to this conclusion because . . .”

- “I’d love to hear your reaction to what I just said.”

- “Do you see any flaws in my reasoning?”

- “Do you see the situation differently?”

Davey provides two additional rules when it comes to what you say:

- Say “and,” not “but.” “When you need to disagree with someone, express your contrary opinion as an ‘and.’ It’s not necessary for someone else to be wrong for you to be right,” she says. When you’re surprised to hear something your counterpart has said, don’t interject with a “But that’s not right!” Just add your perspective. Davey suggests something like this: “You think we need to leave room in the budget for a customer event, and I’m concerned that we need that money for employee training. What are our options?” This will engage your colleague in problem solving, which is inherently collaborative instead of combative.

- Use hypotheticals. Being contradicted doesn’t feel very good, so don’t try to tit-for-tat your counterpart, countering each of his arguments. Instead, says Davey, use hypothetical situations to get him imagining. “Imagining is the opposite of defending, so it gets the brain out of a rut,” she says. She offers this example: “I hear your concern about getting the right salespeople to pull off this campaign. If we could get the right people . . . what could the campaign look like?”

Watch your body language—and your counterpart’s

The words coming out of your mouth should match what you’re saying with your body. Watch your facial expression and what you do with your arms, legs, and entire body. A lot of people unconsciously convey nonverbal messages. Are you slumping your shoulders? Rolling your eyes? Fidgeting with your pen?

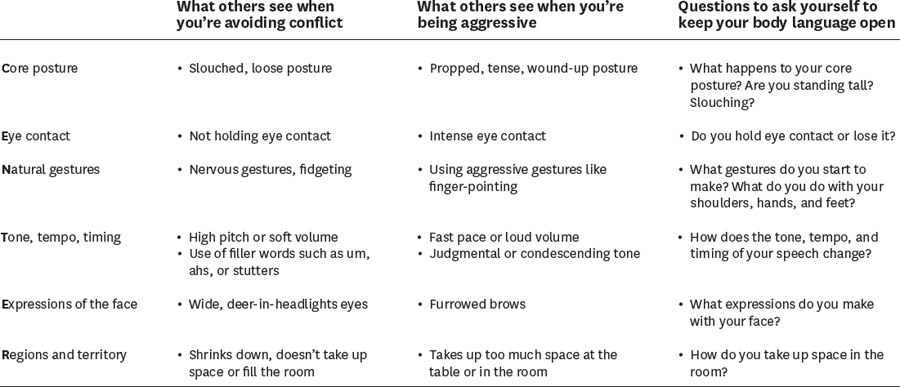

Increase your awareness of the energy you give off. In Amy Jen Su and Muriel Maignan Wilkins’s book, Own the Room, they offer six places where nonverbal messages are communicated through body language: your posture; eye contact; the natural gestures you make typically with your hands; the tone, tempo, and timing of your voice; your facial expressions; and how you occupy the space around you (see table 6-1).

Through each of those points, you signal to others what you’re thinking and feeling. Jen Su and Maignan Wilkins use the acronym CENTER to help people remember these six cue points. Table 6-1 shows different signals you might be sending depending on whether you’re in an aggressive, conflict-seeking mode or a more passive, conflict-avoidant mode. Reviewing the table and considering the questions will help you maintain body language that’s as open as the language you’re using.

During your conversation, pay attention to each of these areas and take stock of the overall impression you’re giving. Do the same for your counterpart. Watch what she’s conveying through her body language. Again, her nonverbal cues may be sending a different message than what she’s articulating. If that’s the case, or if you’re noticing any body language, ask about it. For example, you might say, “I hear you saying that you’re fine with this approach, but it looks as if maybe you still have some concerns. Is that right? Should we talk those through?”

Change the tenor of the conversation

Sometimes, despite your best intentions and all of the time you put into preparing for the conversation, things veer off course. You can’t demand that your counterpart hold the discussion exactly the way you want.

If things get heated, don’t panic. Take a deep breath, mentally pop out of the conversation as if you’re a fly on the wall, and objectively look at what’s happening. You might even describe to yourself (in your head) what’s happening: “He keeps returning to the fact that I yelled at his team yesterday.” “When I try to move the conversation away from what’s gone wrong to what we can do going forward, he keeps shifting it back.” “Every time I bring up the sales numbers, he raises his voice.”

Manage your body language during a conflict

Source: Adapted from Amy Jen Su and Muriel Maignan Wilkins, Own the Room: Discover Your Signature Voice to Master Your Leadership Presence (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2013).

Then state what you’re observing in a calm tone. “It looks as if whenever the sale numbers come up, you raise your voice.” Suggest a different approach: “If we put our heads together, we could probably come up with a way to move past this. Do you have any ideas?”

“Stepping back and explicitly negotiating over the process itself can be a powerful game-changing move,” says Weiss. If it seems as if you’ve entered into a power struggle in which you’re no longer discussing the substance of your conflict but battling over who is right, step back and either return to your questions above or talk about what’s not working. Say, “We seem to be getting locked into our positions. Could we return to our goals and see if we can brainstorm together some new ideas that might meet both our objectives?” See the sidebar “Phrases That Productively Move the Conversation Along.” Returning your counterpart to his original goal may be enough to get the conversation back on track.

PHRASES THAT PRODUCTIVELY MOVE THE CONVERSATION ALONG

- “You may be right, but I’d like to understand more.”

- “I have a completely different perspective, but clearly you think this is unfair, so how can we fix this?”

- “Can you help me make the connection between this and the other issues we’re talking about?”

- “I’d like to give my reaction to what you’ve said so far and see what you think.”

- “I’m sensing there are some intense emotions about this. When you said ‘X,’ I had the impression you were feeling ‘Y.’ If so, I’d like to understand what upset you. Is there something I’ve said or done?”

- “This may be more my perception than yours, but when you said ‘X,’ I felt . . .”

- “Is there anything I can say or do that might convince you to consider other options here?”

When to Bring in a Third Party

There are times, however, when you’re getting nowhere with your counterpart and, even when you follow the principles above, you’re still not able to have a productive discussion. Some problems are too entrenched, complicated, or emotional to sort out between two people. Or your counterpart is too inflexible or unable to hear your side, insisting that it’s her way or the highway.

The main indicator you may need outside help, says White, is when it seems as if your counterpart is perpetuating the conflict rather than trying to solve it. “She may be alternatively conciliatory and antagonistic. Every time you seem to be making progress, she walks back from the tentative agreement and accuses you of not negotiating in good faith,” she explains.

This is not a failure. “Someone who is not involved in the conflict may be able to provide vital perspective for both parties,” says Gerzon. Ideally, you’ll both agree that a third party is necessary before going with this option. But if you can’t reach agreement on anything else, this might be difficult. In these cases, you may have to ask someone else to get involved without your counterpart’s permission.

Who you bring in will depend on the nature of the conflict. Choose someone whom you both trust and can rely on to understand the issues but also brings an outside perspective. It might be one or both of your bosses. “For example,” says Ben Dattner, “if roles are poorly defined, a boss might help clarify who is responsible for what.” If the conflict is over how people are rewarded, you might turn to HR or a union representative. Dattner shares another example: “If incentives reward individual rather than team performance, HR can be called in to help better align incentives with organizational goals.”

When you’ve exhausted all your internal options, or if there is no one to appeal to, you might need a trained mediator to help.

In the process of having a productive discussion with your counterpart—expressing your point of view and listening to hers—a resolution may naturally arise. It may be that there was a misunderstanding and now it’s cleared up. Or perhaps after hearing your colleague out, you realize you do agree with how she’s approaching the project. Or as you talk through what her goals are, you stumble upon a solution that would work well for both of you.

If this doesn’t happen organically, you’ll have to more consciously work toward a resolution that meets both your and your counterpart’s goals.