Cryptography

Introduction

Cryptography is everywhere these days, from hashed passwords to encrypted mail, to Internet Protocol Security (IPSec) virtual private networks (VPNs) and even encrypted filesystems. Security is the reason why people opt to encrypt data, and if you want your data to remain secure you’d best know a bit about how cryptography works. This chapter certainly can’t teach you how to become a professional cryptographer—that takes years of study and practice—but you will learn how most of the cryptography you will come in contact with functions (without all the complicated math, of course).

We’ll examine some of the history of cryptography and then look closely at a few of the most common algorithms, including Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), the recently announced new cryptography standard for the U.S. government. We’ll learn how key exchanges and public key cryptography came into play, and how to use them. I’ll show you how almost all cryptography is at least theoretically vulnerable to brute force attacks.

Naturally, once we’ve covered the background we’ll look at how cryptography can be broken, from cracking passwords to man-in-the-middle-type attacks. We’ll also look at how other attacks based on poor implementation of strong cryptography can reduce your security level to zero. Finally, we’ll examine how weak attempts to hide information using outdated cryptography can easily be broken.

Understanding Cryptography Concepts

What does the word crypto mean? It has its origins in the Greek word kruptos, which means hidden. Thus, the objective of cryptography is to hide information so that only the intended recipient(s) can “unhide” it. In crypto terms, the hiding of information is called encryption, and when the information is unhidden, it is called decryption. A cipher is used to accomplish the encryption and decryption. Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines cipher as “a method of transforming a text in order to conceal its meaning.” The information that is being hidden is called plaintext; once it has been encrypted, it is called ciphertext. The ciphertext is transported, secure from prying eyes, to the intended recipient(s), where it is decrypted back into plaintext.

History

According to Fred Cohen, the history of cryptography has been documented back to over 4000 years ago, where it was first allegedly used in Egypt. Julius Caesar even used his own cryptography called Caesar’s Cipher. Basically, Caesar’s Cipher rotated the letters of the alphabet to the right by three. For example, S moves to V and E moves to H. By today’s standards the Caesar Cipher is extremely simplistic, but it served Julius just fine in his day. If you are interested in knowing more about the history of cryptography, the following site is a great place to start: www.all.net/books/ip/Chap2-1.html.

In fact, ROT13 (rotate 13), which is similar to Caesar’s Cipher, is still in use today. It is not used to keep secrets from people, but more to avoid offending people when sending jokes, spoiling the answers to puzzles, and things along those lines. If such things occur when someone decodes the message, then the responsibility lies on them and not the sender. For example, Mr. G. may find the following example offensive to him if he was to decode it, but as it is shown it offends no one:V guvax Jvaqbjf fhpxf …

ROT13 is simple enough to work out with pencil and paper. Just write the alphabet in two rows; the second row offset by 13 letters:

Encryption Key Types

Cryptography uses two types of keys: symmetric and asymmetric. Symmetric keys have been around the longest; they utilize a single key for both the encryption and decryption of the ciphertext. This type of key is called a secret key, because you must keep it secret. Otherwise, anyone in possession of the key can decrypt messages that have been encrypted with it. The algorithms used in symmetric key encryption have, for the most part, been around for many years and are well known, so the only thing that is secret is the key being used. Indeed, all of the really useful algorithms in use today are completely open to the public.

A couple of problems immediately come to mind when you are using symmetric key encryption as the sole means of cryptography. First, how do you ensure that the sender and receiver each have the same key? Usually this requires the use of a courier service or some other trusted means of key transport. Second, a problem exists if the recipient does not have the same key to decrypt the ciphertext from the sender. For example, take a situation where the symmetric key for a piece of crypto hardware is changed at 0400 every morning at both ends of a circuit. What happens if one end forgets to change the key (whether it is done with a strip tape, patch blocks, or some other method) at the appropriate time and sends ciphertext using the old key to another site that has properly changed to the new key? The end receiving the transmission will not be able to decrypt the ciphertext, since it is using the wrong key. This can create major problems in a time of crisis, especially if the old key has been destroyed. This is an overly simple example, but it should provide a good idea of what can go wrong if the sender and receiver do not use the same secret key.

Asymmetric cryptography is relatively new in the history of cryptography, and it is probably more recognizable to you under the synonymous term public key cryptography. Asymmetric algorithms use two different keys, one for encryption and one for decryption—a public key and a private key, respectively. Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman first publicly released public key cryptography in 1976 as a method of exchanging keys in a secret key system. Their algorithm, called the Diffie-Hellman (DH) algorithm, is examined later in the chapter. Even though it is commonly reported that public key cryptography was first invented by the duo, some reports state that the British Secret Service actually invented it a few years prior to the release by Diffie and Hellman. It is alleged, however, that the British Secret Service never actually did anything with their algorithm after they developed it. More information on the subject can be found at the following location: www.wired.com/wired/archive/7.04/crypto_pr.html

Some time after Diffie and Hellman, Phil Zimmermann made public key encryption popular when he released Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) v1.0 for DOS in August 1991. Support for multiple platforms including UNIX and Amiga were added in 1994 with the v2.3 release. Over time, PGP has been enhanced and released by multiple entities, including ViaCrypt and PGP Inc., which is now part of Network Associates. Both commercial versions and free versions (for noncommercial use) are available. For those readers in the United States and Canada, you can retrieve the free version from http://web.mit.edu/network/pgp.html. The commercial version can be purchased from Network Associates at www.pgp.com.

Learning about Standard Cryptographic Algorithms

Just why are there so many algorithms anyway? Why doesn’t the world just standardize on one algorithm? Given the large number of algorithms found in the field today, these are valid questions with no simple answers. At the most basic level, it’s a classic case of tradeoffs between security, speed, and ease of implementation. Here security indicates the likelihood of an algorithm to stand up to current and future attacks, speed refers to the processing power and time required to encrypt and decrypt a message, and ease of implementation refers to an algorithm’s predisposition (if any) to hardware or software usage. Each algorithm has different strengths and drawbacks, and none of them is ideal in every way. In this chapter, we will look at the five most common algorithms that you will encounter: Data Encryption Standard (DES), AES [Rijndael], International Data Encryption Algorithm (IDEA), Diffie-Hellman, and Rivest, Shamir, Adleman (RSA). Be aware, though, that there are dozens more active in the field.

Understanding Symmetric Algorithms

In this section, we will examine several of the most common symmetric algorithms in use: DES, its successor AES, and the European standard, IDEA. Keep in mind that the strength of symmetric algorithms lies primarily in the size of the keys used in the algorithm, as well as the number of cycles each algorithm employs. All symmetric algorithms are also theoretically vulnerable to brute force attacks, which are exhaustive searches of all possible keys. However, brute force attacks are often infeasible. We will discuss them in detail later in the chapter.

DES

Among the oldest and most famous encryption algorithms is the Data Encryption Standard, which was developed by IBM and was the U.S. government standard from 1976 until about 2001. DES was based significantly on the Lucifer algorithm invented by Horst Feistel, which never saw widespread use. Essentially, DES uses a single 64-bit key—56 bits of data and 8 bits of parity—and operates on data in 64-bit chunks. This key is broken into 16 separate 48-bit subkeys, one for each round, which are called Feistel cycles. Figure 6.1 gives a schematic of how the DES encryption algorithm operates.

Each round consists of a substitution phase, wherein the data is substituted with pieces of the key, and a permutation phase, wherein the substituted data is scrambled (re-ordered). Substitution operations, sometimes referred to as confusion operations, are said to occur within S-boxes. Similarly, permutation operations, sometimes called diffusion operations, are said to occur in P-boxes. Both of these operations occur in the “F Module” of the diagram. The security of DES lies mainly in the fact that since the substitution operations are non-linear, so the resulting ciphertext in no way resembles the original message. Thus, language-based analysis techniques (discussed later in this chapter) used against the ciphertext reveal nothing. The permutation operations add another layer of security by scrambling the already partially encrypted message.

Every five years from 1976 until 2001, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) reaffirmed DES as the encryption standard for the U.S. government. However, by the 1990s the aging algorithm had begun to show signs that it was nearing its end of life. New techniques that identified a shortcut method of attacking the DES cipher, such as differential cryptanalysis, were proposed as early as 1990, though it was still computationally unfeasible to do so.

Significant design flaws such as the short 56-bit key length also affected the longevity of the DES cipher. Shorter keys are more vulnerable to brute force attacks. Although Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman were the first to criticize this short key length, even going so far as to declare in 1979 that DES would be useless within 10 years, DES was not publicly broken by a brute force attack until 1997.

The first successful brute force attack against DES took a large network of machines over 4 months to accomplish. Less than a year later, in 1998, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) cracked DES in less than three days using a computer specially designed for cracking DES. This computer, code-named “Deep Crack,” cost less than $250,000 to design and build. The record for cracking DES stands at just over 22 hours and is held by Distributed.net, which employed a massively parallel network of thousands of systems (including Deep Crack). Add to this the fact that Bruce Schneier has theorized that a machine capable of breaking DES in about six minutes could be built for a mere $10 million. Clearly, NIST needed to phase out DES in favor of a new algorithm.

AES (Rijndael)

In 1997, as the fall of DES loomed ominously closer, NIST announced the search for the Advanced Encryption Standard, the successor to DES. Once the search began, most of the big-name cryptography players submitted their own AES candidates. Among the requirements of AES candidates were:

![]() AES would be a private key symmetric block cipher (similar to DES).

AES would be a private key symmetric block cipher (similar to DES).

![]() AES needed to be stronger and faster then 3-DES.

AES needed to be stronger and faster then 3-DES.

![]() AES required a life expectancy of at least 20-30 years.

AES required a life expectancy of at least 20-30 years.

![]() AES would support key sizes of 128-bits, 192-bits, and 256-bits.

AES would support key sizes of 128-bits, 192-bits, and 256-bits.

![]() AES would be available to all—royalty free, non-proprietary and unpatented.

AES would be available to all—royalty free, non-proprietary and unpatented.

Within months NIST had a total of 15 different entries, 6 of which were rejected almost immediately on grounds that they were considered incomplete. By 1999, NIST had narrowed the candidates down to five finalists including MARS, RC6, Rijndael, Serpent, and Twofish.

Selecting the winner took approximately another year, as each of the candidates needed to be tested to determine how well they performed in a variety of environments. After all, applications of AES would range anywhere from portable smart cards to standard 32-bit desktop computers to high-end optimized 64-bit computers. Since all of the finalists were highly secure, the primary deciding factors were speed and ease of implementation (which in this case meant memory footprint).

Rijndael was ultimately announced as the winner in October of 2000 because of its high performance in both hardware and software implementations and its small memory requirement. The Rijndael algorithm, developed by Belgian cryptographers Dr. Joan Daemen and Dr. Vincent Rijmen, also seems resistant to power- and timing-based attacks.

So how does AES/Rijndael work? Instead of using Feistel cycles in each round like DES, it uses iterative rounds like IDEA (discussed in the next section). Data is operated on in 128-bit chunks, which are grouped into four groups of four bytes each. The number of rounds is also dependent on the key size, such that 128-bit keys have 9 rounds, 192-bit keys have 11 rounds and 256-bit keys require 13 rounds. Each round consists of a substitution step of one S-box per data bit followed by a pseudo-permutation step in which bits are shuffled between groups. Then each group is multiplied out in a matrix fashion and the results are added to the subkey for that round.

How much faster is AES than 3-DES? It’s difficult to say, because implementation speed varies widely depending on what type of processor is performing the encryption and whether or not the encryption is being performed in software or running on hardware specifically designed for encryption. However, in similar implementations, AES is always faster than its 3-DES counterpart. One test performed by Brian Gladman has shown that on a Pentium Pro 200 with optimized code written in C, AES (Rijndael) can encrypt and decrypt at an average speed of 70.2 Mbps, versus DES’s speed of only 28 Mbps. You can read his other results at fp.gladman.plus.com/cryptography_technology/aes.

IDEA

The European counterpart to the DES algorithm is the IDEA algorithm, and its existence proves that Americans certainly don’t have a monopoly on strong cryptography. IDEA was first proposed under the name Proposed Encryption Standard (PES) in 1990 by cryptographers James Massey and Xuejia Lai as part of a combined research project between Ascom and the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. Before it saw widespread use PES was updated in 1991 to increase its strength against differential cryptanalysis attacks and was renamed Improved PES (IPES). Finally, the name was changed to International Data Encryption Algorithm (IDEA) in 1992.

Not only is IDEA newer than DES, but IDEA is also considerably faster and more secure. IDEA’s enhanced speed is due to the fact the each round consists of much simpler operations than the Fiestel cycle in DES. These operations (XOR, addition, and multiplication) are much simpler to implement in software than the substitution and permutation operations of DES.

IDEA operates on 64-bit blocks with a 128-bit key, and the encryption/decryption process uses 8 rounds with 6 16-bit subkeys per round. The IDEA algorithm is patented both in the US and in Europe, but free non-commercial use is permitted.

Understanding Asymmetric Algorithms

Recall that unlike symmetric algorithms, asymmetric algorithms require more than one key, usually a public key and a private key (systems with more than two keys are possible). Instead of relying on the techniques of substitution and transposition, which symmetric key cryptography uses, asymmetric algorithms rely on the use of massively large integer mathematics problems. Many of these problems are simple to do in one direction but difficult to do in the opposite direction. For example, it’s easy to multiply two numbers together, but it’s more difficult to factor them back into the original numbers, especially if the integers you are using contain hundreds of digits. Thus, in general, the security of asymmetric algorithms is dependent not upon the feasibility of brute force attacks, but the feasibility of performing difficult mathematical inverse operations and advances in mathematical theory that may propose new “shortcut” techniques. In this section, we’ll take a look at RSA and Diffie-Hellman, the two most popular asymmetric algorithms in use today.

Diffie-Hellman

In 1976, after voicing their disapproval of DES and the difficulty in handling secret keys, Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman published the Diffie-Hellman algorithm for key exchange. This was the first published use of public key cryptography, and arguably one of the cryptography field’s greatest advances ever. Because of the inherent slowness of asymmetric cryptography, the Diffie-Hellman algorithm was not intended for use as a general encryption scheme—rather, its purpose was to transmit a private key for DES (or some similar symmetric algorithm) across an insecure medium. In most cases, Diffie-Hellman is not used for encrypting a complete message because it is 10 to 1000 times slower than DES, depending on implementation.

Prior to publication of the Diffie-Hellman algorithm, it was quite painful to share encrypted information with others because of the inherent key storage and transmission problems (as discussed later in this chapter). Most wire transmissions were insecure, since a message could travel between dozens of systems before reaching the intended recipient and any number of snoops along the way could uncover the key. With the Diffie-Hellman algorithm, the DES secret key (sent along with a DES-encrypted payload message) could be encrypted via Diffie-Hellman by one party and decrypted only by the intended recipient.

In practice, this is how a key exchange using Diffie-Hellman works:

![]() The two parties agree on two numbers; one is a large prime number, the other is an integer smaller than the prime. They can do this in the open and it doesn’t affect security.

The two parties agree on two numbers; one is a large prime number, the other is an integer smaller than the prime. They can do this in the open and it doesn’t affect security.

![]() Each of the two parties separately generates another number, which they keep secret. This number is equivalent to a private key. A calculation is made involving the private key and the previous two public numbers. The result is sent to the other party. This result is effectively a public key.

Each of the two parties separately generates another number, which they keep secret. This number is equivalent to a private key. A calculation is made involving the private key and the previous two public numbers. The result is sent to the other party. This result is effectively a public key.

![]() The two parties exchange their public keys. They then privately perform a calculation involving their own private key and the other party’s public key. The resulting number is the session key. Each party will arrive at the same number.

The two parties exchange their public keys. They then privately perform a calculation involving their own private key and the other party’s public key. The resulting number is the session key. Each party will arrive at the same number.

![]() The session key can be used as a secret key for another cipher, such as DES. No third party monitoring the exchange can arrive at the same session key without knowing one of the private keys.

The session key can be used as a secret key for another cipher, such as DES. No third party monitoring the exchange can arrive at the same session key without knowing one of the private keys.

The most difficult part of the Diffie-Hellman key exchange to understand is that there are actually two separate and independent encryption cycles happening. As far as Diffie-Hellman is concerned, only a small message is being transferred between the sender and the recipient. It just so happens that this small message is the secret key needed to unlock the larger message.

Diffie-Hellman’s greatest strength is that anyone can know either or both of the sender and recipient’s public keys without compromising the security of the message. Both the public and private keys are actually just very large integers. The Diffie-Hellman algorithm takes advantage of complex mathematical functions known as discrete logarithms, which are easy to perform forwards but extremely difficult to find inverses for. Even though the patent on Diffie-Hellman has been expired for several years now, the algorithm is still in wide use, most notably in the IPSec protocol. IPSec uses the Diffie-Hellman algorithm in conjunction with RSA authentication to exchange a session key that is used for encrypting all traffic that crosses the IPSec tunnel.

RSA

In the year following the Diffie-Hellman proposal, Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard Adleman proposed another public key encryption system. Their proposal is now known as the RSA algorithm, named for the last initials of the researchers. RSA shares many similarities with the Diffie-Hellman algorithm in that RSA is also based on multiplying and factoring large integers. However, RSA is significantly faster than Diffie-Hellman, leading to a split in the asymmetric cryptography field that refers to Diffie-Hellman and similar algorithms as Public Key Distribution Systems (PKDS) and RSA and similar algorithms as Public Key Encryption (PKE). PKDS systems are used as session-key exchange mechanisms, while PKE systems are generally considered fast enough to encrypt reasonably small messages. However, PKE systems like RSA are not considered fast enough to encrypt large amounts of data like entire filesystems or high-speed communications lines.

Because of the former patent restrictions on RSA, the algorithm saw only limited deployment, primarily only from products by RSA Security, until the mid-1990s. Now you are likely to encounter many programs making extensive use of RSA, such as PGP and Secure Shell (SSH). The RSA algorithm has been in the public domain since RSA Security placed it there two weeks before the patent expired in September 2000. Thus the RSA algorithm is now freely available for use by anyone, for any purpose.

Understanding Brute Force

Just how secure are encrypted files and passwords anyway? Consider that there are two ways to break an encryption algorithm—brute force and various cryptanalysis shortcuts. Cryptanalysis shortcuts vary from algorithm to algorithm, or may even be non-existent for some algorithms, and they are always difficult to find and exploit. Conversely, brute force is always available and easy to try. Brute force techniques involve exhaustively searching the given keyspace by trying every possible key or password combination until the right one is found.

Brute Force Basics

As an example, consider the basic three-digit combination bicycle lock where each digit is turned to select a number between zero and nine. Given enough time and assuming that the combination doesn’t change during the attempts, just rolling through every possible combination in sequence can easily open this lock. The total number of possible combinations (keys) is 103 or 1000, and let’s say the frequency, or number of combinations a thief can attempt during a time period, is 30 per minute. Thus, the thief should be able to open the bike lock in a maximum of 1000/(30 per min) or about 33 minutes. Keep in mind that with each new combination attempted, the number of remaining possible combinations (keyspace) decreases and the chance of guessing the correct combination (deciphering the key) on the next attempt increases.

Brute force always works because the keyspace, no matter how large, is always finite. So the way to resist brute force attacks is to choose a keysize large enough that it becomes too time-consuming for the attacker to use brute force techniques. In the bike lock example, three digits of keyspace gives the attacker a maximum amount of time of 33 minutes required to steal the bicycle, so the thief may be tempted to try a brute force attack. Suppose a bike lock with a five-digit combination is used. Now there are 100,000 possible combinations, which would take about 55.5 hours for the thief check by brute force. Clearly, most thieves would move on and look for something easier to steal.

When applied to symmetric algorithms such as DES, brute force techniques work very similarly to the bike lock example. In fact, this happens to be exactly the way DES was broken by the EFF’s “Deep Crack.” Since the DES key is known to be 56 bits long, every possible combination of keys between a string of 56 zeros and a string of 56 ones is tested until the appropriate key is discovered.

As for the distributed attempts to break DES, the five-digit bike lock analogy needs to be slightly changed. Distributed brute force attempts are analogous to having multiple thieves, each with an exact replica of the bike lock. Each of these replicas has the exact same combination as the original bike lock, and the thieves work on the combination in parallel. Suppose there are 50 thieves working together to guess the combination. Each thief tries a different set of 2,000 combinations such that no two thieves are working on the same combination set (sub-keyspace). Now instead of testing 30 combinations per minute, the thieves are testing 1500 combinations per minute, and all possible combinations will be checked in about 67 minutes. Recall that it took the single thief 55 hours to steal the bike, but now 50 thieves working together can steal the bike in just over an hour. Distributed computing applications working under the same fundamentals are what allowed Distributed.net to crack DES in less than 24 hours.

Applying brute force techniques to RSA and other public key encryption systems is not quite as simple. Since the RSA algorithm is broken by factoring, if the keys being used are sufficiently small (far, far smaller than any program using RSA would allow), it is conceivable that a person could crack the RSA algorithm using pencil and paper. However, for larger keys, the time required to perform the factoring becomes excessive. Factoring does not lend itself to distributed attacks as well, either. A distributed factoring attack would require much more coordination between participants than simple exhaustive keyspace coordination. There are projects, such as the www-factoring project (www.npac.syr.edu/factoring.html), that endeavor to do just this. Currently, the www-factoring project is attempting to factor a 130-digit number. In comparison, 512-bit keys are about 155 digits in size.

Using Brute Force to Obtain Passwords

Brute force is a method commonly used to obtain passwords, especially if the encrypted password list is available. While the exact number of characters in a password is usually unknown, most passwords can be estimated to be between 4 and 16 characters. Since only about 100 different values can be used for each character of the password, there are only about 1004 to 10016 likely password combinations. Though massively large, the number of possible password combinations is finite and is therefore vulnerable to brute force attack.

Before specific methods for applying brute force can be discussed, a brief explanation of password encryption is required. Most modern operating systems use some form of password hashing to mask the exact password. Because passwords are never stored on the server in cleartext form, the password authentication system becomes much more secure. Even if someone unauthorized somehow obtains the password list, he will not be able to make immediate use of it, hopefully giving system administrators time to change all of the relevant passwords before any real damage is caused.

Passwords are generally stored in what is called hashed format. When a password is entered on the system it passes through a one-way hashing function, such as Message Digest 5 (MD5), and the output is recorded. Hashing functions are one-way encryption only, and once data has been hashed, it cannot be restored. A server doesn’t need to know what your password is. It needs to know that you know what it is. When you attempt to authenticate, the password you provided is passed through the hashing function and the output is compared to the stored hash value. If these values match, then you are authenticated. Otherwise, the login attempt fails, and is (hopefully) logged by the system.

Brute force attempts to discover passwords usually involve stealing a copy of the username and hashed password listing and then methodically encrypting possible passwords using the same hashing function. If a match is found, then the password is considered cracked. Some variations of brute force techniques involve simply passing possible passwords directly to the system via remote login attempts. However, these variations are rarely seen anymore due to account lockout features and the fact that they can be easily spotted and traced by system administrators. They also tend to be extremely slow.

Appropriate password selection minimizes—but cannot completely eliminate—a password’s ability to be cracked. Simple passwords, such as any individual word in a language, make the weakest passwords because they can be cracked with an elementary dictionary attack. In this type of attack, long lists of words of a particular language called dictionary files are searched for a match to the encrypted password. More complex passwords that include letters, numbers and symbols require a different brute force technique that includes all printable characters and generally take an order of magnitude longer to run.

Some of the more common tools used to perform brute force password attacks include L0phtcrack for Windows passwords, and Crack and John the Ripper for UNIX passwords. Not only do hackers use these tools but security professionals also find them useful in auditing passwords. If it takes a security professional N days to crack a password, then that is approximately how long it will take an attacker to do the same. Each of these tools will be discussed briefly, but be aware that written permission should always be obtained from the system administrator before using these programs against a system.

L0phtcrack

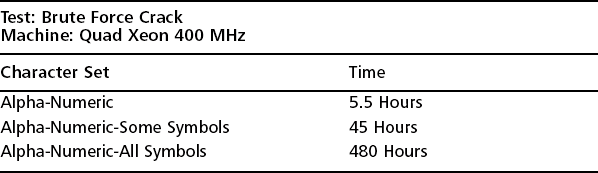

L0phtCrack is a Windows NT password-auditing tool from the L0pht that came onto the scene in 1997. It provides several different mechanisms for retrieving the passwords from the hashes, but is used primarily for its brute force capabilities. The character sets chosen dictate the amount of time and processing power necessary to search the entire keyspace. Obviously, the larger the character set chosen, the longer it will take to complete the attack. However, dictionary based attacks, which use only common words against the password database are normally quite fast and often effective in catching the poorest passwords. Table 6.1 lists the time required for L0phtcrack 2.5 to crack passwords based on the character set selected.

Table 6.1

L0phtcrack 2.5 Brute Force Crack Time Using a Quad Xeon 400 MHz Processor

Used with permission of the L0pht

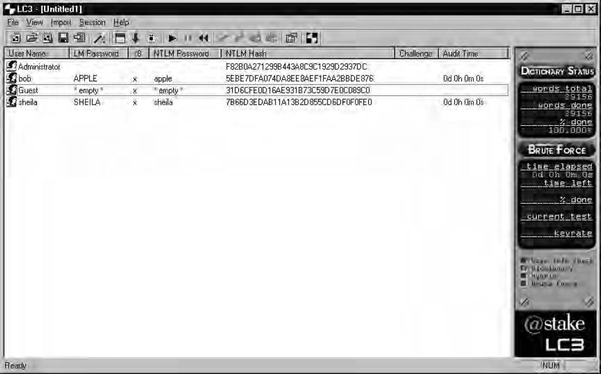

L0pht Heavy Industries, the developers of L0phtcrack, have since sold the rights to the software to @stake Security. Since the sale, @stake has released a program called LC3, which is intended to be L0phtcrack’s successor. LC3 includes major improvements over L0phtcrack 2.5, such as distributed cracking and a simplified sniffing attachment that allows password hashes to be sniffed over Ethernet. Additionally, LC3 includes a password-cracking wizard to help the less knowledgeable audit their system passwords. Figure 6.2 shows LC3 displaying the output of a dictionary attack against some sample user passwords.

LC3 reflects a number of usability advances since the older L0phtcrack 2.5 program, and the redesigned user interface is certainly one of them. Both L0phtCrack and LC3 are commercial software packages. However, a 15-day trial can be obtained at www.atstake.com/research/lc3/download.html.

Crack

The oldest and most widely used UNIX password cracking utility is simply called Crack. Alec Muffett is the author of Crack, which he calls a password-guessing program for UNIX systems. It runs only on UNIX systems against UNIX passwords, and is for the most part a dictionary-based program. However, in the latest release available (v5.0a from 1996), Alec has bundled Crack7, a brute force password cracker that can be used if a dictionary-based attack fails. One of the most interesting aspects of this combination is that Crack can test for common variants that people use when they think they are picking more secure passwords. For example, instead of “password,” someone may choose “pa55word.” Crack has user-configurable permutation rules that will catch these variants. More information on Alec Muffett and Crack is available at www.users.dircon.co.uk/˜crypto.

John the Ripper

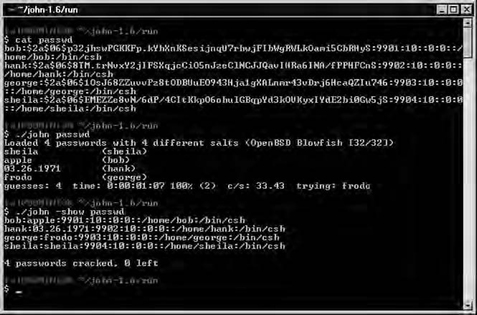

John the Ripper is another password-cracking program, but it differs from Crack in that it is available in UNIX, DOS, and Win32 editions. Crack is great for older systems using crypt(), but John the Ripper is better for newer systems using MD5 and similar password formats. John the Ripper is used primarily for UNIX passwords, but there are add-ons available to break other types of passwords, such as Windows NT LanManager (LANMAN) hashes and Netscape Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) server passwords. John the Ripper supports brute force attacks in incremental mode. Because of John the Ripper’s architecture, one of its most useful features is its ability to save its status automatically during the cracking process, which allows for aborted cracking attempts to be restarted even on a different system. John the Ripper is part of the OpenWall project and is available from www.openwall.com/john.

A sample screenshot of John the Ripper is shown in Figure 6.3. In this example, a sample section of a password file in OpenBSD format is cracked using John the Ripper. Shown below the password file snippet is the actual output of John the Ripper as it runs. You can see that each cracked password is displayed on the console. Be aware that the time shown to crack all four passwords is barely over a minute only because I placed the actual passwords at the top of the “password.lst” listing, which John uses as its dictionary. Real attempts to crack passwords would take much longer. After John has cracked a password file, you can have John display the password file in unshadowed format using the show option.

Knowing When Real Algorithms Are Being Used Improperly

While theoretically, given enough time, almost any encryption standard can be cracked with brute force, it certainly isn’t the most desirable method to use when “theoretically enough time” is longer than the age of the universe. Thus, any shortcut method that a hacker can use to break your encryption will be much more desirable to him than brute force methods.

None of the encryption algorithms discussed in this chapter have any serious flaws associated with the algorithms themselves, but sometimes the way the algorithm is implemented can create vulnerabilities. Shortcut methods for breaking encryption usually result from a vendor’s faulty implementation of a strong encryption algorithm, or lousy configuration from the user. In this section, we’ll discuss several incidents of improperly used encryption that are likely to be encountered in the field.

Bad Key Exchanges

Because there isn’t any authentication built into the Diffie-Hellman algorithm, implementations that use Diffie-Hellman-type key exchanges without some sort of authentication are vulnerable to man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks. The most notable example of this type of behavior is the SSH-1 protocol. Since the protocol itself does not authenticate the client or the server, it’s possible for someone to cleverly eavesdrop on the communications. This deficiency was one of the main reasons that the SSH-2 protocol was completely redeveloped from SSH-1. The SSH-2 protocol authenticates both the client and the server, and warns of or prevents any possible MITM attacks, depending on configuration, so long as the client and server have communicated at least once. However, even SSH-2 is vulnerable to MITM attacks prior to the first key exchange between the client and the server.

As an example of a MITM-type attack, consider that someone called Al is performing a standard Diffie-Hellman key exchange with Charlie for the very first time, while Beth is in a position such that all traffic between Al and Charlie passes through her network segment. Assuming Beth doesn’t interfere with the key exchange, she will not be able to read any of the messages passed between Al and Charlie, because she will be unable to decrypt them. However, suppose that Beth intercepts the transmissions of Al and Charlie’s public keys and she responds to them using her own public key. Al will think that Beth’s public key is actually Charlie’s public key and Charlie will think that Beth’s public key is actually Al’s public key.

When Al transmits a message to Charlie, he will encrypt it using Beth’s public key. Beth will intercept the message and decrypt it using her private key. Once Beth has read the message, she encrypts it again using Charlie’s public key and transmits the message on to Charlie. She may even modify the message contents if she so desires. Charlie then receives Beth’s modified message, believing it to come from Al. He replies to Al and encrypts the message using Beth’s public key. Beth again intercepts the message, decrypts it with her private key, and modifies it. Then she encrypts the new message with Al’s public key and sends it on to Al, who receives it and believes it to be from Charlie.

Clearly, this type of communication is undesirable because a third party not only has access to confidential information, but she can also modify it at will. In this type of attack, no encryption is broken because Beth does not know either Al or Charlie’s private keys, so the Diffie-Hellman algorithm isn’t really at fault. Beware of the key exchange mechanism used by any public key encryption system. If the key exchange protocol does not authenticate at least one and preferably both sides of the connection, it may be vulnerable to MITM-type attacks. Authentication systems generally use some form of digital certificates (usually X.509), such as those available from Thawte or VeriSign.

Hashing Pieces Separately

Older Windows-based clients store passwords in a format known as LanManager (LANMAN) hashes, which is a horribly insecure authentication scheme. However, since this chapter is about cryptography, we will limit the discussion of LANMAN authentication to the broken cryptography used for password storage.

As with UNIX password storage systems, LANMAN passwords are never stored on a system in cleartext format—they are always stored in a hash format. The problem is that the hashed format is implemented in such a way that even though DES is used to encrypt the password, the password can still be broken with relative ease. Each LANMAN password can contain up to 14 characters, and all passwords less than 14 characters are padded to bring the total password length up to 14 characters. During encryption the password is split into a pair of seven-character passwords, and each of these seven-character passwords is encrypted with DES. The final password hash consists of the two concatenated DES-encrypted password halves.

Since DES is known to be a reasonably secure algorithm, why is this implementation flawed? Shouldn’t DES be uncrackable without significant effort? Not exactly. Recall that there are roughly 100 different characters that can be used in a password. Using the maximum possible password length of 14 characters, there should be about 10014 or 1.0x1028 possible password combinations. LANMAN passwords are further simplified because there is no distinction between upper-and lowercase letters—all letters appears as uppercase. Furthermore, if the password is less than eight characters, then the second half of the password hash is always identical and never even needs to be cracked. If only letters are used (no numbers or punctuation), then there can only be 267 (roughly eight billion) password combinations. While this may still seem like a large number of passwords to attack via brute force, remember that these are only theoretical maximums and that since most user passwords are quite weak, dictionary-based attacks will uncover them quickly. The bottom line here is that dictionary-based attacks on a pair of seven-character passwords (or even just one) are much faster than those on single 14-character passwords.

Suppose that strong passwords that use two or more symbols and numbers are used with the LANMAN hashing routine. The problem is that most users tend to just tack on the extra characters at the end of the password. For example, if a user uses his birthplace along with a string of numbers and symbols, such as “MONTANA45%,” the password is still insecure. LANMAN will break this password into the strings “MONTANA” and “45%.” The former will probably be caught quickly in a dictionary-based attack, and the latter will be discovered quickly in a brute force attack because it is only three characters. For newer business-oriented Microsoft operating systems such as Windows NT and Windows 2000, LANMAN hashing can and should be disabled in the registry if possible, though this will make it impossible for Win9x clients to authenticate to those machines.

Using a Short Password to Generate a Long Key

Password quality is a subject that we have already briefly touched upon in our discussion of brute force techniques. With the advent of PKE encryption schemes such as PGP, most public and private keys are generated using passwords or passphrases, leaving the password generation steps vulnerable to brute force attacks. If a password is selected that is not of significant length, that password can be brute force attacked in an attempt to generate the same keys as the user. Thus PKE systems such as RSA have a chance to be broken by brute force, not because of any deficiency in the algorithm itself, but because of deficiencies in the key generation process. The best way to protect against these types of roundabout attacks is to use strong passwords when generating any sort of encryption key. Strong passwords include the use of upper- and lowercase letters, numbers, and symbols, preferably throughout the password. Eight characters is generally considered the minimum length for a strong password, but given the severity of choosing a poor password for key generation, I recommend you use at least twelve characters for these instances.

High quality passwords are often said to have high entropy, which is a semifinite measurement that attempts to quantify the relative quality of a password. Longer passwords typically have more entropy than shorter passwords, and the more random each character of the password is, the more entropy in the password. For example, the password “albatross” (about 30 bits of entropy) might be reasonably long in length, but has less entropy than a totally random password of the same length such as “g8%=MQ+p” (about 48 bits of entropy). Since the former might appear in a list of common names for bird species, while the latter would never appear in a published list, obviously the latter is a stronger and therefore more desirable password. The moral of the story here is that strong encryption such as 168-bit 3-DES can be broken easily if the secret key has only a few bits of entropy.

Improperly Stored Private or Secret Keys

Let’s say you have only chosen to use the strong cryptography algorithms, you have verified that there are not any flaws in the vendors’ implementations, and you have generated your keys with great care. How secure is your data now? It is still only as secure as your private or secret key. These keys must be safeguarded at all costs, or you may as well not even use encryption.

Since keys are simply strings of data, they are usually stored in a file somewhere in your system’s hard disk. For example, private keys for SSH-1 are stored in the identity file located in the .ssh directory under a user’s home directory. If the filesystem permissions on this file allow others to access the file, then this private key is compromised. Once others have your private or secret key, reading your encrypted communications becomes trivial. (Note that the SSH identity file is used for authentication, not encryption; but you get the idea.)

However, in some vendor implementations, your keys could be disclosed to others because the keys are not stored securely in RAM. As you are aware, any information processed by a computer, including your secret or private key, is located in the computer’s RAM at some point. If the operating system’s kernel does not store these keys in a protected area of its memory, they could conceivably become available to someone who dumps a copy of the system’s RAM to a file for analysis. These memory dumps are called core dumps in UNIX, and they are commonly created during a denial of service (DoS) attack. Thus a successful hacker could generate a core dump on your system and extract your key from the memory image. In a similar attack, a DoS attack could cause excess memory usage on the part of the victim, forcing the key to be swapped to disk as part of virtual memory. Fortunately, most vendors are aware of this type of exploit by now, and it is becoming less and less common since encryption keys are now being stored in protected areas of memory.

Understanding Amateur Cryptography Attempts

If your data is not being protected by one of the more modern, computationally secure algorithms that we’ve already discussed in this chapter, or some similar variant, then your data is probably not secure. In this section, we’re going to discover how simple methods of enciphering data can be broken using rudimentary cryptanalysis.

Classifying the Ciphertext

Even a poorly encrypted message often looks indecipherable at first glance, but you can sometimes figure out what the message is by looking beyond just the stream of printed characters. Often, the same information that you can “read between the lines” on a cleartext message still exists in an enciphered message.

For the mechanisms discussed below, all the “secrecy” is contained in the algorithm, not in a separate key. Our challenge for these is to figure out the algorithm used. So for most of them, that means that we will run a password or some text through the algorithm, which will often be available to us in the form of a program or other black box device. By controlling the inputs and examining the outputs, we hope to determine the algorithm. This will enable us to later take an arbitrary output and determine what the input was.

Frequency Analysis

The first and most powerful method you can employ to crack simple ciphertext is frequency analysis, which is based on the idea that certain letters are used more often than others. For example, I can barely write a single word in this sentence that doesn’t include the letter e. How can letter frequency be of use? You can create a letter frequency table for your ciphertext, assuming the message is of sufficient length, and compare that table to one charting the English language (there are many available). That would give you some clues about which characters in the ciphertext might match up with cleartext letters.

The astute reader will discover that some letters appear with almost identical frequency. How then can you determine which letter is which? You can either evaluate how the letters appear in context, or you can consult other frequency tables that note the appearance of multiple letter combinations such as sh, ph, ie and the.

Crypto of this type is just a little more complicated than the Caesar Cipher mentioned at the beginning of the chapter. This was state-of-the-art hundreds of years ago. Now problems of this type are used in daily papers for commuter entertainment, under the titles of “Cryptogram,” “CryptoQuote,” or similar. Still, some people will use this method as a token effort to hide things. This type of mechanism, or ones just slightly more complex, show up in new worms and viruses all the time.

Ciphertext Relative Length Analysis

Sometimes the ciphertext can provide you with clues to the cleartext even if you don’t know how the ciphertext was encrypted. For example, suppose that you have an unknown algorithm that encrypts passwords such that you have available the original password and a ciphertext version of that password. If the length or size of each is the same, then you can infer that the algorithm produces output in a 1:1 ratio to the input. You may even be able to input individual characters to obtain the ciphertext translation for each character. If nothing else, you at least know how many characters to specify for an unknown password if you attempt to break it using a brute force method.

If you know that the length of a message in ciphertext is identical to the length of a message in cleartext, you can leverage this information to pick out pieces of the ciphertext for which you can make guesses about the cleartext. For example, during WWII while the Allies were trying to break the German Enigma codes, they used a method similar to the above because they knew the phrase “Heil Hitler” probably appeared somewhere near the end of each transmission.

Similar Plaintext Analysis

A related method you might use to crack an unknown algorithm is to compare changes in the ciphertext output with changes in the cleartext input. Of course, this method requires that you have access to the algorithm to selectively encode your carefully chosen cleartext. For example, try encoding the strings “AAAAAA,” “AAAAAB” and “BAAAAA” and note the difference in the ciphertext output. For monoalphabetic ciphers, you might expect to see the first few characters remain the same in both outputs for the first two, with only the last portion changing. If so, then it’s almost trivial to construct a full translation table for the entire algorithm that maps cleartext input to ciphertext output and vice versa. Once the translation table is complete, you could write an inverse function that deciphers the ciphertext back to plaintext without difficulty.

What happens if the cipher is a polyalphabetic cipher, where more than one character changes in the ciphertext for single character changes in cleartext? Well, that becomes a bit trickier to decipher, depending on the number of changes to the ciphertext. You might be able to combine this analysis technique with brute force to uncover the inner workings of the algorithm, or you might not.

Monoalphabetic Ciphers

A monoalphabetic cipher is any cipher in which each character of the alphabet is replaced by another character in a one-to-one ratio. Both the Caesar Cipher and ROT13, mentioned earlier in the chapter, are classic examples of monoalphabetic ciphers. Some monoalphabetic ciphers scramble the alphabet instead of shifting the letters, so that instead of having an alphabet of ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ, the cipher alphabet order might be MLNKBJVHCGXFZDSAPQOWIEURYT. The new scrambled alphabet is used to encipher the message such that M=A, L=B … T=Z. Using this method, the cleartext message “SECRET” becomes “OBNQBW.”

You will rarely find these types of ciphers in use today outside of word games because they can be easily broken by an exhaustive search of possible alphabet combinations and they are also quite vulnerable to the language analysis methods we described. Monoalphabetic ciphers are absolutely vulnerable to frequency analysis because even though the letters are substituted, the ultimate frequency appearance of each letter will roughly correspond to the known frequency characteristics of the language.

Other Ways to Hide Information

Sometimes vendors follow the old “security through obscurity” approach, and instead of using strong cryptography to prevent unauthorized disclosure of certain information, they just try to hide the information using a commonly known reversible algorithm like UUEncode or Base64, or a combination of two simple methods. In these cases, all you need to do to recover the cleartext is to pass the ciphertext back through the same engine. Vendors may also use XOR encoding against a certain key, but you won’t necessarily need the key to decode the message. Let’s look at some of the most common of these algorithms in use.

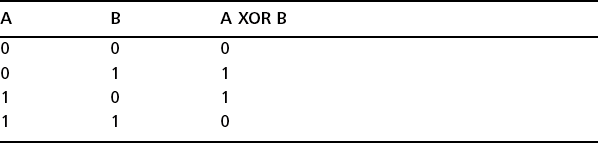

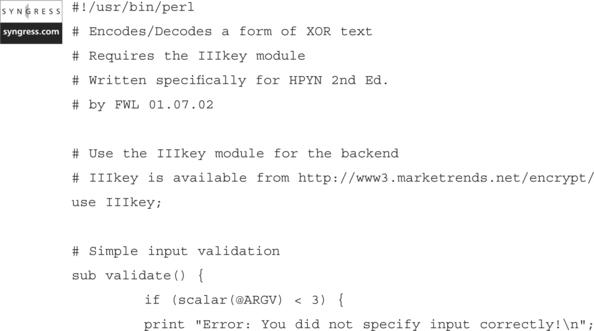

XOR

While many of the more complex and secure encryption algorithms use XOR as an intermediate step, you will often find data obscured by a simple XOR operation. XOR is short for exclusive or, which identifies a certain type of binary operation with a truth table as shown in Table 6.2. As each bit from A is combined with B, the result is “0” only if the bits in A and B are identical. Otherwise, the result is 1.

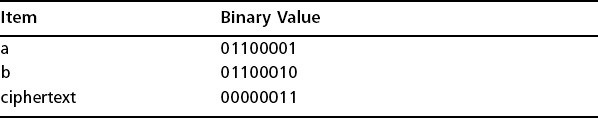

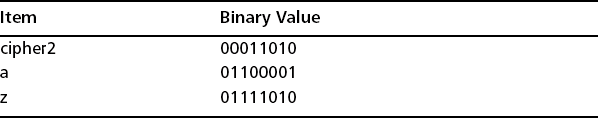

Let’s look at a very simple XOR operation and how you can undo it. In our simple example, we will use a single character key (“a”) to obscure a single character message (“b”) to form a result that we’ll call “ciphertext” (see Table 6.3).

Suppose that you don’t know what the value of “a” actually is, you only know the value of “b” and the resulting “ciphertext.” You want to recover the key so that you can find out the cleartext value of another encrypted message, “cipher2,” which is 00011010. You could perform an XOR with “b” and the “ciphertext” to recover the key “a,” as shown in Table 6.4.

Once the key is recovered, you can use it to decode “cipher2” into the character “z” (see Table 6.5).

Of course, this example is somewhat oversimplified. In the real world, you are most likely to encounter keys that are multiple characters instead of just a single character, and the XOR operation may occur a number of times in series to obscure the message. In this type of instance, you can use a null value to obtain the key—that is, the message will be constructed such that it contains only 0s.

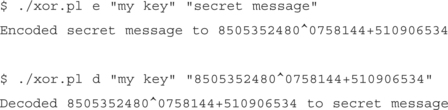

Abstract 1 and 0 manipulation like this can be difficult to understand if you are not used to dealing with binary numbers and values. Therefore, I’ll provide you with some sample code and output of a simple program that uses a series of 3 XOR operations on various permutations of a key to obscure a particular message. This short Perl program uses the freely available IIIkey module for the back-end XOR encryption routines. You will need to download IIIkey from www3.marketrends.net/encrypt/ to use this program.

UUEncode

UUEncode is a commonly used algorithm for converting binary data into a text-based equivalent for transport via e-mail. As you probably know, most e-mail systems cannot directly process binary attachments to e-mail messages. So when you attach a binary file (such as a JPEG image) to an e-mail message, your e-mail client takes care of converting the binary attachment to a text equivalent, probably through an encoding engine like UUEncode. The attachment is converted from binary format into a stream of printable characters, which can be processed by the mail system. Once received, the attachment is processed using the inverse of the encoding algorithm (UUDecode), resulting in conversion back to the original binary file.

Sometimes vendors may use the UUEncode engine to encode ordinary printable text in order to obscure the message. When this happens, all you need to do to is pass the encoded text through a UUDecode program to discern the message. Command-line UUEncode/UUDecode clients are available for just about every operating system ever created.

Base64

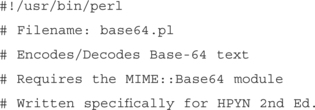

Base64 is also commonly used to encode e-mail attachments similar to UUEncode, under Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (MIME) extensions. However, you are also likely to come across passwords and other interesting information hidden behind a Base64 conversion. Most notably, many Web servers that implement HTTP-based basic authentication store password data in Base64 format. If your attacker can get access to the Base64 encoded username and password set, he or she can decode them in seconds, no brute force required. One of the telltale signs that a Base64 encode has occurred is the appearance of one or two equal signs (=) at the end of the string, which is often used to pad data.

Look at some sample code for converting between Base64 data and cleartext. This code snippet should run on any system that has Perl5 or better with the MIME:: Base64 module from CPAN (www.cpan.org). We have also given you a couple of usage samples.

![]()

![]()

Compression

Sometimes you may find that compression has been weakly used to conceal information from you. In days past, some game developers would compress the size of their save game files not only to reduce space, but also to limit your attempts to modify it with a save game editor. The most commonly used algorithms for this were SQSH (Squish or Squash) and LHA. The algorithms themselves were somewhat inherited from console games of the 1980s, where they were used to compress the ROM images in the cartridges. As a rule, when you encounter text that you cannot seem to decipher via standard methods, you may want to check to see if the information has been compressed using one of the plethora of compression algorithms available today.

Summary

This chapter looked into the meaning of cryptography and some of its origins, including the Caesar Cipher. More modern branches of cryptography are symmetric and asymmetric cryptography, which are also known as secret key and public key cryptography, respectively.

The most common symmetric algorithms in use today include DES, AES, and IDEA. Since DES is showing its age, we looked at how NIST managed the development of AES as a replacement, and how Rijndael was selected from five finalists to become the AES algorithm. From the European perspective, we saw how IDEA came to be developed in the early 1990s and examined its advantages over DES.

The early development of asymmetric cryptography was begun in the mid-1970s by Diffie and Hellman, who developed the Diffie-Hellman key exchange algorithm as a means of securely exchanging information over a public network. After Diffie-Hellman, the RSA algorithm was developed, heralding a new era of public key cryptography systems such as PGP. Fundamental differences between public key and symmetric cryptography include public key cryptography’s reliance on the factoring problem for extremely large integers.

Brute force is an effective method of breaking most forms of cryptography, provided you have the time to wait for keyspace exhaustion, which could take anywhere from several minutes to billions of years. Cracking passwords is the most widely used application of brute force; programs such as L0phtcrack and John the Ripper are used exclusively for this purpose.

Even secure algorithms can be implemented insecurely, or in ways not intended by the algorithm’s developers. Man-in-the-middle attacks could cripple the security of a Diffie-Hellman key exchange, and even DES-encrypted LANMAN password hashes can be broken quite easily. Using easily broken passwords or passphrases as secret keys in symmetric algorithms can have unpleasant effects, and improperly stored private and secret keys can negate the security provided by encryption altogether.

Information is sometimes concealed using weak or reversible algorithms. We saw in this chapter how weak ciphers are subject to frequency analysis attacks that use language characteristics to decipher the message. Related attacks include relative length analysis and similar plaintext analysis. We saw how vendors sometimes conceal information using XOR and Base64 encoding and looked at some sample code for each of these types of reversible ciphers. We also saw how, on occasion, information is compressed as a means of obscuring it.

Solutions Fast Track

Understanding Cryptography Concepts

![]() Unencrypted text is referred to as cleartext, while encrypyted text is called ciphertext.

Unencrypted text is referred to as cleartext, while encrypyted text is called ciphertext.

![]() The two main categories of cryptography are symmetric key and asymmetric key cryptography. Symmetric key cryptography uses a single secret key, while asymmetric key cryptography uses a pair of public and private keys.

The two main categories of cryptography are symmetric key and asymmetric key cryptography. Symmetric key cryptography uses a single secret key, while asymmetric key cryptography uses a pair of public and private keys.

![]() Public key cryptography was first devised as a means of exchanging a secret key securely by Diffie and Hellman.

Public key cryptography was first devised as a means of exchanging a secret key securely by Diffie and Hellman.

Learning about Standard Cryptographic Algorithms

![]() The reason why so many cryptographic algorithms are available for your use is that each algorithm has its own relative speed, security and ease of use. You need to know enough about the most common algorithms to choose one that is appropriate to the situation to which it will be applied.

The reason why so many cryptographic algorithms are available for your use is that each algorithm has its own relative speed, security and ease of use. You need to know enough about the most common algorithms to choose one that is appropriate to the situation to which it will be applied.

![]() Data Encryption Standard (DES) is the oldest and most widely known modern encryption method around. However, it is nearing the end of its useful life span, so you should avoid using it in new implementations or for information you want to keep highly secure.

Data Encryption Standard (DES) is the oldest and most widely known modern encryption method around. However, it is nearing the end of its useful life span, so you should avoid using it in new implementations or for information you want to keep highly secure.

![]() Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) was designed as a secure replacement for DES, and you can use several different keysizes with it.

Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) was designed as a secure replacement for DES, and you can use several different keysizes with it.

![]() Be aware that asymmetric cryptography uses entirely different principles than symmetric cryptography. Where symmetric cryptography combines a single key with the message for a number of cycles, asymmetric cryptography relies on numbers that are too large to be factored.

Be aware that asymmetric cryptography uses entirely different principles than symmetric cryptography. Where symmetric cryptography combines a single key with the message for a number of cycles, asymmetric cryptography relies on numbers that are too large to be factored.

![]() The two most widely used asymmetric algorithms are Diffie-Hellman and RSA.

The two most widely used asymmetric algorithms are Diffie-Hellman and RSA.

Understanding Brute Force

![]() Brute force is the one single attack that will always succeed against symmetric cryptography, given enough time. You want to ensure that “enough time” becomes a number of years or decades or more.

Brute force is the one single attack that will always succeed against symmetric cryptography, given enough time. You want to ensure that “enough time” becomes a number of years or decades or more.

![]() An individual machine performing a brute force attack is slow. If you can string together a number of machines in parallel, your brute force attack will be much faster.

An individual machine performing a brute force attack is slow. If you can string together a number of machines in parallel, your brute force attack will be much faster.

![]() Brute force attacks are most often used for cracking passwords.

Brute force attacks are most often used for cracking passwords.

Knowing When Real Algorithms Are Being Used Improperly

![]() Understand the concept of the man-in-the-middle attack against a Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

Understand the concept of the man-in-the-middle attack against a Diffie-Hellman key exchange.

![]() LANMAN password hashing should be disabled, if possible, because its implementation allows it to be broken quite easily.

LANMAN password hashing should be disabled, if possible, because its implementation allows it to be broken quite easily.

![]() Key storage should always be of the utmost importance to you because if your secret or private key is compromised, all data protected by those keys is also compromised.

Key storage should always be of the utmost importance to you because if your secret or private key is compromised, all data protected by those keys is also compromised.

Understanding Amateur Cryptography Attempts

![]() You can crack almost any weak cryptography attempts (like XOR) with minimal effort.

You can crack almost any weak cryptography attempts (like XOR) with minimal effort.

![]() Frequency analysis is a powerful tool to use against reasonably lengthy messages that aren’t guarded by modern cryptography algorithms.

Frequency analysis is a powerful tool to use against reasonably lengthy messages that aren’t guarded by modern cryptography algorithms.

![]() Sometimes vendors will attempt to conceal information using weak cryptography (like Base64) or compression.

Sometimes vendors will attempt to conceal information using weak cryptography (like Base64) or compression.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following Frequently Asked Questions, answered by the authors of this book, are designed to both measure your understanding of the concepts presented in this chapter and to assist you with real-life implementation of these concepts. To have your questions about this chapter answered by the author, browse to www.syngress.com/solutions and click on the “Ask the Author” form.

Q: Are there any cryptography techniques which are 100 percent secure?

A: Yes. Only the One Time Pad (OTP) algorithm is absolutely unbreakable if implemented correctly. The OTP algorithm is actually a Vernam cipher, which was developed by AT&T way back in 1917. The Vernam cipher belongs to a family of ciphers called stream ciphers, since they encrypt data in continuous stream format instead of the chunk-by-chunk method of block ciphers. There are two problems with using the OTP, however: You must have a source of truly random data, and the source must be bit-for-bit as long as the message to be encoded. You also have to transmit both the message and the key (separately), the key must remain secret, and the key can never be reused to encode another message. If an eavesdropper intercepts two messages encoded with the same key, then it is trivial for the eavesdropper to recover the key and decrypt both messages. The reason OTP ciphers are not used more commonly is the difficulty in collecting truly random numbers for the key (as mentioned in one of the sidebars for this chapter) and the difficulty of the secure distribution of the key.

Q: How long is DES expected to remain in use?

A: Given the vast number of DES-based systems, I expect we’ll continue to see DES active for another five or ten years, especially in areas where security is not a high priority. For some applications, DES is considered a “good enough” technology since the average hacker doesn’t have the resources available (for now) to break the encryption scheme efficiently. I predict that DES will still find a use as a casual eavesdropping deterrent, at least until the widespread adoption of IPv6. DES is also far faster than 3-DES, and as such it is more suitable to older-style VPN gear that may not be forward-compatible with the new AES standard. In rare cases where legacy connections are required, the government is still allowing new deployment of DES-based systems.

Q: After the 9/11 attacks I’m concerned about terrorists using cryptography, and I’ve heard people advocate that the government should have a back door access to all forms of encryption. Why would this be a bad idea?

A: Allowing back-door access for anyone causes massive headaches for users of encryption. First and foremost, these back door keys are likely to be stored all in one place, making that storage facility the prime target for hackers. When the storage facility is compromised, and I have no doubt that it would be (the only question is how soon), everyone’s data can effectively be considered compromised. We’d also need to establish a new bureaucracy that would be responsible for handing out the back door access, probably in a manner similar to the way in which wiretaps are currently doled out. We would also require some sort of watchdog group that certifies the deployment group as responsible. Additionally, all of our encryption schemes would need to be redesigned to allow backdoor access, probably in some form of “public key + trusted key” format. Implementation of these new encryption routines would take months to develop and years to deploy. New cracking schemes would almost certainly focus on breaking the algorithm through the “trusted key” access, leaving the overall security of these routines questionable at best.

Q: Why was CSS, the encryption technology used to protect DVDs from unauthorized copying, able to be broken so easily?

A: Basically, DVD copy protection was broken so easily because one entity, Xing Technologies, left their key lying around in the open, which as we saw in this chapter is a cardinal sin. The data encoded on a DVD-Video disc is encrypted using an algorithm called the Content Scrambling System (CSS) which can be unlocked using a 40-bit key. Using Xing’s 40-bit key, hackers were able to brute force and guess at the keys for over 170 other licensees at a rapid pace. That way, since the genie was out of the bottle, so to speak, for so many vendors, the encryption for the entire format was basically broken. With so many keys to choose from, others in the underground had no difficulty in leveraging these keys to develop the DeCSS program, which allows data copied off of the DVD to be saved to another media in an unencrypted format. Ultimately, the CSS scheme was doomed to failure. You can’t put a key inside millions of DVD players, distribute them, and not expect someone to eventually pull it out.