Prognostication in Patients Receiving Palliative Radiation Therapy

M.S. Krishnan, Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Centers, Boston, MA, United States

Abstract

Predicting prognosis in patients with advanced, incurable cancer is one of the most difficult tasks faced by oncologists, and yet it is one of the most vital. Unfortunately, physicians have been shown to have poor accuracy at predicting prognosis. Typical tools that are used for patients with curable cancers are often not applicable in this patient population. This chapter highlights the data regarding the importance of prognostication, physician accuracy, and patient wishes regarding prognosis discussions. It then details factors that can be used to aid in prognosis prediction, such as performance status, clinical symptoms, and laboratory values. Finally, it discusses four prognostic models that incorporate these factors in order to divide patients into prognostic groups that can be used in clinical practice.

Keywords

Prognosis; palliative; metastatic; cancer

Introduction

Importance of Prognostication

• Prognostication (prediction of life expectancy) is one of the most difficult tasks faced by oncologists. It is particularly difficult in patients with advanced, incurable cancer as life expectancy in these patients can vary from days to months.

• However, it is also an essential skill as it can inform treatment decisions, including the type and aggressiveness of treatment as well as the decision to enroll on hospice.

• Hospice referrals require a physician predicted prognosis of ≤6 months.

• Patients who hold overly optimistic perceptions of their prognosis are more likely to want futile, aggressive care [1].

• Patients are more likely to defer aggressive medical care that is associated with lower quality of life near death, greater medical care costs, and worse caregiver bereavement outcomes when physicians provide prognostic information during end-of-life discussions [2–4].

• In theory, estimating prognosis can help with tailoring treatment to life expectancy

![]() In a US SEER study, 18% of patients who received radiation therapy in the last month of life spent 10 of their last 30 days of life receiving radiation therapy [5].

In a US SEER study, 18% of patients who received radiation therapy in the last month of life spent 10 of their last 30 days of life receiving radiation therapy [5].

![]() In a study of 216 patients referred for palliative radiation therapy, 27% of patients spent 81–100% of their remaining lifespan on treatment [6].

In a study of 216 patients referred for palliative radiation therapy, 27% of patients spent 81–100% of their remaining lifespan on treatment [6].

Physician Accuracy

• Estimates of physician accuracy in prediction of life expectancy range from 20% to 60% [7–12].

• Physicians tend to communicate overly optimistic prognostic information to patients [7,10,12].

• Several physician related factors can influence predictions of survival

![]() Length of the patient–physician relationship: Each year that a physician has known a patient has been shown to increase the likelihood of making an erroneous prediction by 12% per year [13].

Length of the patient–physician relationship: Each year that a physician has known a patient has been shown to increase the likelihood of making an erroneous prediction by 12% per year [13].

![]() Accuracy has not been found to be dependent on physician seniority [14].

Accuracy has not been found to be dependent on physician seniority [14].

![]() Physicians tend to lack confidence in estimating life expectancy [15], which has been shown to make them more likely to withhold prognostic information [16,17].

Physicians tend to lack confidence in estimating life expectancy [15], which has been shown to make them more likely to withhold prognostic information [16,17].

What Patients Want to Hear

• The majority of patients desire at least some information regarding their prognosis.

• The amount of information desired and desired manner of communication varies from patient to patient.

• Two studies assessing patient preferences showed similar outcomes. One studied 126 patients with incurable metastatic disease in Australia and the other assessed 352 cancer patients in Michigan, USA

![]() About 80% of patients wanted to know average survival rates and qualitative prognostic information [18,19].

About 80% of patients wanted to know average survival rates and qualitative prognostic information [18,19].

![]() About 60% of patients wanted to discuss expected survival rates when first diagnosed with their illness [18,19].

About 60% of patients wanted to discuss expected survival rates when first diagnosed with their illness [18,19].

![]() About 15% of patients who expressed a preference to receive qualitative prognostic information did not receive it [18,19].

About 15% of patients who expressed a preference to receive qualitative prognostic information did not receive it [18,19].

![]() Only about half of patients wanted to receive quantitative prognostic information [18,19].

Only about half of patients wanted to receive quantitative prognostic information [18,19].

Prognostic Factors

• Tumor size, stage, grade, and genetics do not play as significant a role in predicting prognosis of patients with incurable disease.

• Other factors have been studied to determine if they help physicians estimate prognosis in patients with incurable cancer

• Performance status has been identified in numerous analyses as a potential prognostic indicator in patients with advanced cancer [20–22].

![]() Tseng et al. assessed 113 physicians to determine what factors were important to them in determining life expectancy. Ninety two percent of these physicians indicated that performance status was “very important” when assessing a patient’s life expectancy.

Tseng et al. assessed 113 physicians to determine what factors were important to them in determining life expectancy. Ninety two percent of these physicians indicated that performance status was “very important” when assessing a patient’s life expectancy.

![]() Performance status has been shown to be primarily helpful for predicting prognosis when it is in the middle to low range [22,23].

Performance status has been shown to be primarily helpful for predicting prognosis when it is in the middle to low range [22,23].

![]() Steep deterioration in Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) can indicate a serious worsening of prognosis [22–24].

Steep deterioration in Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) can indicate a serious worsening of prognosis [22–24].

![]() Prognostic utility of KPS has been shown to increase when combined with clinical symptoms, such as edema, dyspnea at rest, and delirium [24,25]

Prognostic utility of KPS has been shown to increase when combined with clinical symptoms, such as edema, dyspnea at rest, and delirium [24,25]

• Clinical symptoms can be used in addition to performance status to help in predicting life expectancy

![]() Cachexia-Anorexia syndrome: Loosely defined as anorexia and involuntary weight loss.

Cachexia-Anorexia syndrome: Loosely defined as anorexia and involuntary weight loss.

– Thought to occur because of imbalanced interactions between inflammatory cytokines, neuropeptides, hormones, and tumor-derived products [26].

– Has been shown to be related to poor survival in patients with metastatic cancer [27].

– In a study of 484 patients with metastatic cancer receiving palliative care consults, longer survival was seen among patients with neither anorexia nor weight loss as compared to patients having anorexia and/or weight loss [27].

![]() Several other symptoms have been noted to be related to survival, particularly when used in combination with each other

Several other symptoms have been noted to be related to survival, particularly when used in combination with each other

– In a study of 181 hospitalized patients referred to a palliative care team, multivariate analysis showed that nausea, dysphagia, dyspnea, confusion, and absence of a depressed mood were independent prognostic factors for worse survival [28]. The authors commented that the absence of a depressed mood may be related to worse survival because patients with a depressed mood may get earlier psychosocial and palliative intervention. However, they admit that the correlation is largely unexplained.

– In that same study, patient survival time decreased with increasing number of the above symptoms: patients with four risk factors had a 60% absolute increased risk of dying at 1 month compared to those with no risk factors [28].

![]() Symptoms must be used cautiously, given the subjectivity involved and difficulty in accurately assessing these symptoms at the end of life.

Symptoms must be used cautiously, given the subjectivity involved and difficulty in accurately assessing these symptoms at the end of life.

![]() Further research required to establish the most predictive and reliably assessable symptoms.

Further research required to establish the most predictive and reliably assessable symptoms.

![]() Laboratory values have also been identified as potential markers for life expectancy

Laboratory values have also been identified as potential markers for life expectancy

![]() Elevated levels of LDH have been associated with numerous types of cancer [29,30]

Elevated levels of LDH have been associated with numerous types of cancer [29,30]

– LDH thought to be a potential marker for higher disease burden and a potential prognostic indicator in patients with metastatic disease.

– In a study of 93 terminal cancer patients, median survival time in patients with LDH <313 was 27 days as compared to 14 days in the elevated LDH group [31].

![]() C-reactive protein (CRP) is any acute phase reactant that responds to inflammation, injury, and cancer

C-reactive protein (CRP) is any acute phase reactant that responds to inflammation, injury, and cancer

– Acute phase reactant that responds to inflammation, injury, and cancer.

– In a study of 44 patients with incurable cancer admitted to a palliative care unity, patients with a CRP of ≥2.2 had a significantly shorter survival than patients with a CRP <2.2, with a hazard ratio of 3.22 [32].

![]() Leukocytosis/lymphopenia have both been suggested as poor prognostic markers in nonhematologic malignancies [33,34].

Leukocytosis/lymphopenia have both been suggested as poor prognostic markers in nonhematologic malignancies [33,34].

– In a study of 252 hospitalized patients with nonhematological malignancies, leukocytosis was associated with a significantly shorter mean survival time [35].

– In a study of 1051 cancer patients receiving chemotherapy with either advanced Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma or metastatic breast cancer, lymphocyte count ≤700/μL was identified as independent risk factor for early death (death within 31 days after chemotherapy delivery) [36].

![]() While laboratory values are promising tools for predicting prognosis, they must be used with caution.

While laboratory values are promising tools for predicting prognosis, they must be used with caution.

![]() Data regarding laboratory values is limited and available studies are small.

Data regarding laboratory values is limited and available studies are small.

![]() Laboratory values are not always readily available in this patient population.

Laboratory values are not always readily available in this patient population.

Prognostic Models

• Various models have been created which incorporate all of the above factors in order to predict prognosis.

• These models vary in terms of their ease of use and accuracy as well as the specific patient population that they apply to.

• A detailed review of prognostic models has been performed elsewhere [37]. Several models also exist that are site-specific (i.e., brain metastases, spinal cord compression). For the purposes of this handbook, four major prognostic models focusing on patients with any type of advanced cancer are reviewed below. (Please see Appendix for additional details.)

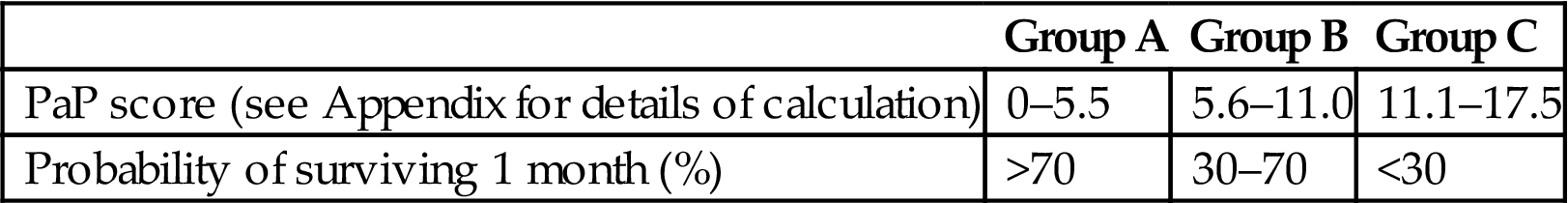

• Palliative Prognostic Score (PaP): Prospective, multicenter study of 519 patients with advanced solid tumors and no longer receiving chemotherapy [38]:

![]() Developed a prognostic model to divide patients into distinct prognostic groups using independent predictors of survival.

Developed a prognostic model to divide patients into distinct prognostic groups using independent predictors of survival.

![]() Final model included anorexia, dyspnea, KPS, total white blood cell count (WBC), lymphopenia, and physician’s survival prediction in weeks.

Final model included anorexia, dyspnea, KPS, total white blood cell count (WBC), lymphopenia, and physician’s survival prediction in weeks.

![]() Patients divided into three groups based on numerical score determined by relative weight of the different prognostic factors and the probability of surviving 1 month (Table 3.1, see book Appendix for calculation of score).

Patients divided into three groups based on numerical score determined by relative weight of the different prognostic factors and the probability of surviving 1 month (Table 3.1, see book Appendix for calculation of score).

![]() Validated in 451 patients entering hospice programs and in a separate population of 100 patients with advanced cancers being cared for by oncologists [39].

Validated in 451 patients entering hospice programs and in a separate population of 100 patients with advanced cancers being cared for by oncologists [39].

![]() Helpful to predict survival at 30 days but not as useful to predict survival in patients with longer life expectancies.

Helpful to predict survival at 30 days but not as useful to predict survival in patients with longer life expectancies.

• Palliative Prognostic Index (PPI): Prospective study of 150 terminally ill cancer patients admitted to a palliative care unit and expected to live ≤6 months [40]:

![]() Model created to divide patients into three prognostic groups based on predictors of survival. The study assessed the palliative performance score (PPS, a modified version of the Karnofsky Performance Status) as well as 20 other clinical symptoms.

Model created to divide patients into three prognostic groups based on predictors of survival. The study assessed the palliative performance score (PPS, a modified version of the Karnofsky Performance Status) as well as 20 other clinical symptoms.

![]() Final model included the PPS, oral intake, edema, dyspnea at rest, and delirium and specifically assessed likelihood of living to 3 and 6 weeks, respectively (see book Appendix for calculation of score).

Final model included the PPS, oral intake, edema, dyspnea at rest, and delirium and specifically assessed likelihood of living to 3 and 6 weeks, respectively (see book Appendix for calculation of score).

![]() Using cut-off point of PPI >6, survival of less than 3 weeks predicted with sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 87%.

Using cut-off point of PPI >6, survival of less than 3 weeks predicted with sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 87%.

![]() Using cut-off point of PPI >4, survival of less than 6 weeks predicted with sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 85%.

Using cut-off point of PPI >4, survival of less than 6 weeks predicted with sensitivity of 70% and specificity of 85%.

![]() Validated in two prospective studies of hospice patients [41].

Validated in two prospective studies of hospice patients [41].

![]() Useful for predicting survival in patients with short survivals, but limited use in estimation of long-term survival (>6 weeks).

Useful for predicting survival in patients with short survivals, but limited use in estimation of long-term survival (>6 weeks).

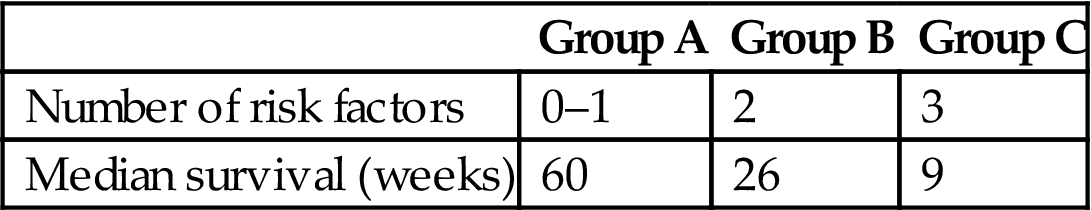

• Number of Risk Factors model (NRF): Retrospective review of 395 patients seen in a radiation oncology department [20]:

![]() Goal of this study was to create a simplified prognostic model that would split patients into distinct survival groups.

Goal of this study was to create a simplified prognostic model that would split patients into distinct survival groups.

![]() Final model consisted of primary cancer site (breast vs nonbreast), the site of metastasis (bone only vs metastases including nonbone sites) and KPS (>60 vs ≤60).

Final model consisted of primary cancer site (breast vs nonbreast), the site of metastasis (bone only vs metastases including nonbone sites) and KPS (>60 vs ≤60).

![]() Three groups created based on the number of risk factors (nonbreast cancer, nonbony metastases, KPS <60) (Table 3.2).

Three groups created based on the number of risk factors (nonbreast cancer, nonbony metastases, KPS <60) (Table 3.2).

![]() Externally validated in 467 patients referred for radiation therapy at Princess Margaret Hospital [20].

Externally validated in 467 patients referred for radiation therapy at Princess Margaret Hospital [20].

![]() Easy to use, but developed in select population receiving palliative radiation therapy, less useful for patients with shorter life expectancies.

Easy to use, but developed in select population receiving palliative radiation therapy, less useful for patients with shorter life expectancies.

• TEACHH Model: Retrospective study of 862 patients receiving palliative radiation at one radiation oncology center [42]:

![]() Model created to divide patients into three distinct prognostic groups, focusing on the extremes of the prognostic spectrum (i.e., patients living <2 months and patients living >1 year).

Model created to divide patients into three distinct prognostic groups, focusing on the extremes of the prognostic spectrum (i.e., patients living <2 months and patients living >1 year).

![]() Final model consisted of Type of cancer (breast and prostate vs other), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (0–1 vs 2–4), Age at treatment (<60 vs ≥60), prior palliative Chemotherapy (0 vs ≥1 course), Hospitalizations in the last 3 months (0 vs ≥1) and the presence of Hepatic metastases.

Final model consisted of Type of cancer (breast and prostate vs other), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (0–1 vs 2–4), Age at treatment (<60 vs ≥60), prior palliative Chemotherapy (0 vs ≥1 course), Hospitalizations in the last 3 months (0 vs ≥1) and the presence of Hepatic metastases.

![]() Three groups created based on the number of risk factors (nonbreast/nonprostate cancer, ECOG PS 2–4, age ≥60, receipt of prior palliative chemotherapy, being hospitalized within the last 3 months and having hepatic metastases) (Table 3.3).

Three groups created based on the number of risk factors (nonbreast/nonprostate cancer, ECOG PS 2–4, age ≥60, receipt of prior palliative chemotherapy, being hospitalized within the last 3 months and having hepatic metastases) (Table 3.3).

![]() Patients grouped in order to identify those at the extremes of the prognostic spectrum (i.e., living longer than 1 year or <2 months) to aid in treatment decision making. The median survival of patients in group C is <2 months and of Group A is more than a year.

Patients grouped in order to identify those at the extremes of the prognostic spectrum (i.e., living longer than 1 year or <2 months) to aid in treatment decision making. The median survival of patients in group C is <2 months and of Group A is more than a year.

![]() Large sample size and identifies patients at the extremes of the prognostic spectrum, but unable to provide ranges of life expectancy for each grouping. Also, it is specific to patients receiving palliative radiation therapy.

Large sample size and identifies patients at the extremes of the prognostic spectrum, but unable to provide ranges of life expectancy for each grouping. Also, it is specific to patients receiving palliative radiation therapy.

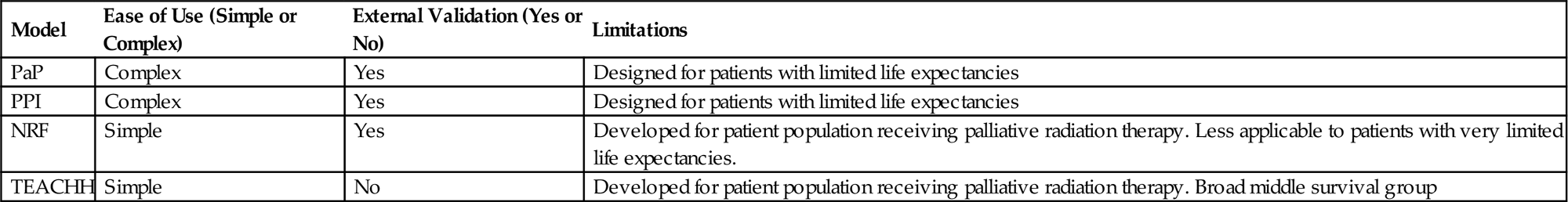

• Each model has specific strengths and weaknesses (Table 3.4).

• The ideal model would be both easy to use and apply across the prognostic spectrum.

Table 3.1

Prognostic Groups From PaP Prognostic Model

| Group A | Group B | Group C | |

| PaP score (see Appendix for details of calculation) | 0–5.5 | 5.6–11.0 | 11.1–17.5 |

| Probability of surviving 1 month (%) | >70 | 30–70 | <30 |

Table 3.2

Prognostic Groups From NRF Model

| Group A | Group B | Group C | |

| Number of risk factors | 0–1 | 2 | 3 |

| Median survival (weeks) | 60 | 26 | 9 |

Table 3.3

Prognostic Groups From TEACHH Model

| Group A | Group B | Group C | |

| TEACHH number of risk factors | 0–1 | 2–4 | 5–6 |

| Median survival (months) | 19.9 | 5.0 | 1.7 |

Table 3.4

Comparison of Prognostic Models

| Model | Ease of Use (Simple or Complex) | External Validation (Yes or No) | Limitations |

| PaP | Complex | Yes | Designed for patients with limited life expectancies |

| PPI | Complex | Yes | Designed for patients with limited life expectancies |

| NRF | Simple | Yes | Developed for patient population receiving palliative radiation therapy. Less applicable to patients with very limited life expectancies. |

| TEACHH | Simple | No | Developed for patient population receiving palliative radiation therapy. Broad middle survival group |

Future Directions

• While various prognostic markers and prognostic models exist to determine prognosis, none are without limitations.

• Existing models do not incorporate treatment-related factors [43], which are becoming increasingly important in patients with metastatic cancer.

• Future research must focus on incorporating treatment-related factors into models as well as developing more refined models that can be used with increased reliability.

• For now, prognostic factors and models should be used as a guide in making treatment-related decisions and should be used with all other available information including patient goals and values.