Palliative Radiotherapy for Advanced and Metastatic Gynecologic and Genitourinary Malignancies

E.C. Fields, M.S. Anscher and A.I. Urdaneta, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States

Abstract

Locally advanced, metastatic, and recurrent pelvic malignancies, including gynecologic and genitourinary (GU) cancers, can cause severe symptoms. Common symptoms at presentation of gynecologic cancers include vaginal bleeding, foul-smelling discharge, pelvic pain, and obstructive symptoms related to compression of the pelvic viscera and lymphatic vessels. In the case of GU malignancies hematuria, urinary retention, or obstruction, dysuria and pelvic pain are the most common symptoms requiring palliative intervention

Radiation therapy is effective for palliation of advanced gynecologic and GU malignancies, particularly for hemostasis of vaginal bleeding, hematuria, and relief of pain.

Keywords

Gynecologic malignancies; genitourinary malignancies; palliative radiotherapy; hypofractionated radiotherapy

Introduction

Locally advanced, metastatic and recurrent pelvic malignancies, including gynecologic and genitourinary (GU) cancers, can cause severe symptoms. Common symptoms at presentation of gynecologic cancers include vaginal bleeding, foul-smelling discharge, pelvic pain, and obstructive symptoms related to compression of the pelvic viscera and lymphatic vessels. In the case of GU malignancies hematuria, urinary retention, or obstruction, dysuria, and pelvic pain are the most common symptoms requiring palliative intervention [1–3].

Bleeding is common with vulvar, vaginal, cervical, endometrial, and ovarian cancers and is typically related to tumor friability and invasion of the vasculature. Similarly, malignancies arising from the urinary tract will most commonly present with hematuria due to tumor friability and destruction of the local anatomy. Complete urinary obstruction often is related to interruption in the normal urine outflow by tumors arising from the bladder, prostate, and urethra and less commonly by very advanced vaginal, vulvar, and cervical tumors. Pelvic pain can be related directly to the tumor mass due to extension to the pelvic side wall and/or floor with nerve compression/invasion, or pressure on other structures of the pelvis including the bones and viscera. Obstruction related to compression of the small and large bowel, or lymphatic structures can cause various symptoms including nausea, vomiting, colicky abdominal pain, lymphedema, and deep venous thrombosis.

Radiation therapy (RT) is effective for palliation of common symptoms associated with advanced gynecologic and GU malignancies, particularly for hemostasis of vaginal bleeding, hematuria, and relief of pain. There are various published techniques for delivering palliative RT, including high-dose single-fraction regimens, hypofractionated short-course regimens, brachytherapy, and transvaginal electron cone therapy.

Evaluation

Female Patients

• Complete history including gynecologic history and symptoms (vaginal bleeding, discharge, pelvic pain).

• Careful examination with a thorough abdominal and pelvic exam, including vaginal, bimanual, and rectovaginal exam. May need examination under anesthesia (EUA) with cystoscopy and proctoscopy in conjunction with gynecologic oncologist to best determine site of bleeding.

• Biopsy for histologic confirmation typically done. However for emergent circumstances, e.g., in a patient with a clinical cervical cancer with intractable vaginal bleeding despite vaginal packing, biopsy may be omitted or delayed until stabilized.

• Labs including complete blood counts (CBC) to assess hemodynamic stability, blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/creatinine to assess renal function, basic metabolic panel for electrolytes, and liver function tests (LFTs) for liver function.

• Clinical and imaging evaluation of extent of disease for staging and to determine whether to proceed with palliative or definitive management. Usually at least a computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis (CAP), but positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are also helpful in cervical cancer to determine extent of metastatic and locoregional disease, respectively.

Male Patients

• Complete history including urinary symptoms (frequency, obstructive symptoms, hematuria, dysuria), pelvic pain, bowel function, erectile function.

• Careful examination with a thorough abdominal and pelvic exam including digital rectal examination (DRE).

• Biopsy for histologic confirmation typically done. May be omitted or delayed in setting of enlarged, firm prostate gland and significantly elevated prostate specific antigen (PSA).

• Labs including CBC to assess hemodynamic stability; BUN/creatinine to assess renal function; LFTs for liver function, PSA, and testosterone; alkaline phosphatase for early measure of bone involvement.

• Clinical and imaging evaluation of extent of disease for staging and to determine whether to proceed with palliative or definitive management. Usually at least a CT CAP, but bone scan and/or pelvic MRI can also be helpful to determine extent of metastatic and locoregional disease, respectively.

All Patients

Treatment Recommendations

• There are various doses and fractionation schedules that have been published for palliation of pelvic symptoms related to gynecologic and GU malignancies (Table 1).

• The decision on which schema to use should be based on the goals of care, whether the expected outcome is palliative versus definitive, expected symptom control is short-term versus durable and whether side effects will be tolerated.

![]() For most patients with symptomatic advanced pelvic disease the goals of care are durable palliation with minimal time commitment and minimal toxicities.

For most patients with symptomatic advanced pelvic disease the goals of care are durable palliation with minimal time commitment and minimal toxicities.

![]() Other considerations for particular schemas include patient performance status, life expectancy, prior treatments, and patient convenience.

Other considerations for particular schemas include patient performance status, life expectancy, prior treatments, and patient convenience.

Primary Gynecologic Malignancies

Most of the data reported for gynecologic malignancies lump together all five major primary disease sites (vulvar, vagina, cervix, uterus, and ovarian cancers). The studies described below focus mainly on the fractionation schemes used and specific sites are mentioned where indicated (Table 16.1).

Table 16.1

Summary of Dose and Fractionation of Palliative Regimens for Gynecologic Malignancies

10 Gy × 1

• The most simple hypofractionated radiotherapy regimen that has been well-documented for use in palliation of gynecologic malignancies is whole pelvic treatment with 10 Gy in a single fraction with repeat doses up to three total treatments given every 4 weeks.

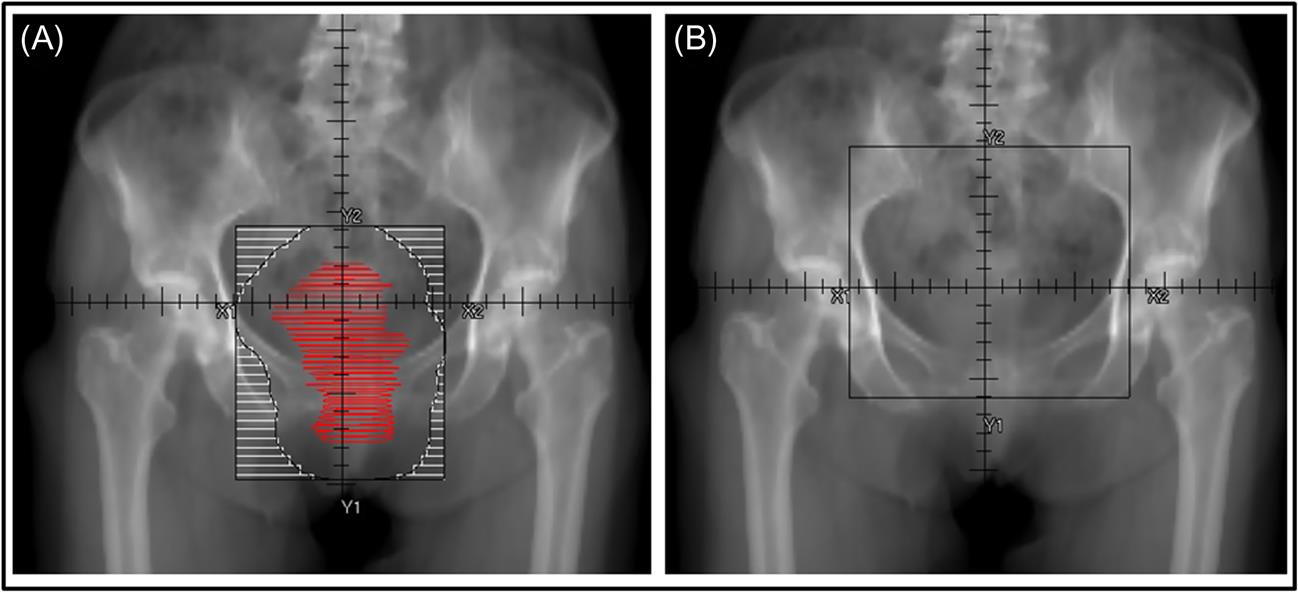

![]() The standard pelvic fields used are typically either AP/PA or a four-field box and include from L5/S1 superiorly to the lower edge of the obturator foramen inferiorly with 1–2 cm outside the pelvic brim laterally, usually not larger than 15×15 cm, but sometimes extended to 18×18 cm to cover nodal or vaginal/vulvar extension (Fig. 16.1B).

The standard pelvic fields used are typically either AP/PA or a four-field box and include from L5/S1 superiorly to the lower edge of the obturator foramen inferiorly with 1–2 cm outside the pelvic brim laterally, usually not larger than 15×15 cm, but sometimes extended to 18×18 cm to cover nodal or vaginal/vulvar extension (Fig. 16.1B).

![]() For repeated treatments, the field is typically reduced to account for tumor regression.

For repeated treatments, the field is typically reduced to account for tumor regression.

![]() Boulware et al. from M.D. Anderson Cancer Center reported on this technique in the late 1970s [4]. They treated 86 women between 1954 and 1975 with 10 Gy×1 and added subsequent treatments in patients with a favorable clinical response.

Boulware et al. from M.D. Anderson Cancer Center reported on this technique in the late 1970s [4]. They treated 86 women between 1954 and 1975 with 10 Gy×1 and added subsequent treatments in patients with a favorable clinical response.

– In total, 31 women received 1 fraction, 35 received 2 fractions, and 20 all 3 fractions.

– Response was evaluated clinically during follow up examinations and in women who received a greater number of treatments; there was increased control of vaginal bleeding, 45%, 85%, and 100% for 1, 2, and 3 treatments.

– Median survival in each group was low, only 3 months, 7 months, and 9 months, respectively, and treatment durability was not addressed.

– Of the gynecologic cancers included, the best response to treatment was in women with cervical, vaginal, and vulvar cancers, and was poor in endometrial and ovarian cancers, possibly suggesting that these histologies are less responsive to this regimen. However, as discussed below, this regimen has been used successfully in women with ovarian cancer.

![]() Similarly, Hodson et al., Chafe et al., and Halle et al. published single-institution experiences with this regimen from 1983 to 1986 which included a total of 69 patients treated in North America with 90–100% response in rates of vaginal bleeding [5–7].

Similarly, Hodson et al., Chafe et al., and Halle et al. published single-institution experiences with this regimen from 1983 to 1986 which included a total of 69 patients treated in North America with 90–100% response in rates of vaginal bleeding [5–7].

– In the study by Hodson et al., all of the 27 patients received 3 fractions for a total of 30 Gy to the pelvis given over 3 months.

– The other two reports were both from the University of North Carolina with the initial report by Dr. Chafe and a longer-term follow up by Dr. Halle which ultimately included 42 patients. Of these patients, 25 received 1 fraction and 17 continued with subsequent fractions “to further reduce bulky disease in the pelvis or control continued bleeding.”

– In patients with follow-up there was 90% CR or PR of bleeding with initial treatment, but only 27% remained permanently free from bleeding. Tumor control rates were initially 25% at 6 months and declined to 14% at 12 months.

– Minimal acute toxicity was originally reported, but in the follow-up by Halle et al. there was a 12% rate of serious treatment complications, 80% of which occurred >10 months posttreatment.

– Unlike the prior study from MDACC, neither improved outcomes nor increased rates of toxicities were correlated with increased number of fractions received. The authors’ conclusion was that this is good treatment for patients with a life expectancy <1 year [4].

![]() RTOG 7905 was published in 1987 and was a Phase I/II trial in 46 patients with advanced pelvic malignancies (43% gynecologic cancers) using the same radiotherapy regimen with 10 Gy repeated at 4-week intervals for a total of three treatments [8].

RTOG 7905 was published in 1987 and was a Phase I/II trial in 46 patients with advanced pelvic malignancies (43% gynecologic cancers) using the same radiotherapy regimen with 10 Gy repeated at 4-week intervals for a total of three treatments [8].

– This study added misonidazole, a radiosensitizer which depletes radioprotective thiols and induces the formation of free radicals thereby sensitizing hypoxic cells to the cytotoxic effects of ionizing radiation, at a dose of 4 g/m2 4–6 hours prior to RT.

– Eighty percent (37 patients) completed all 3 treatments, with 6 achieving CR, 10 PR, 19 minimal or no response, and the remainders were not able to be evaluated due to no follow-up.

– The study closed early due to unacceptably high rates of late GI toxicity: 11% grade 3, 19% grade 4, and projected 49% grade 3 or greater by 1 year.

![]() Single-fraction palliative RT is still used (without radiosensitizers) and has been reported by Onsrud et al. from Norway and Mishra et al. from India in 2001 and 2005, respectively [9,10].

Single-fraction palliative RT is still used (without radiosensitizers) and has been reported by Onsrud et al. from Norway and Mishra et al. from India in 2001 and 2005, respectively [9,10].

– Mishra et al. showed particularly good results in 100 patients with 100% relief of vaginal bleeding, 49% relief of vaginal discharge, and 33% relief of pain.

– Symptom assessment was performed after each fraction. Relief of vaginal bleeding increased with each fraction from 31% after the first fraction to 100% after the third fraction. Interestingly, relief from vaginal discharge and pain were rated highest at the evaluation following the second fraction. There is no information reported on the durability of symptom control.

– Vomiting and diarrhea were the most common acute side effects and at a median follow-up of 9 months, late effects were minimal with 4% subcutaneous fibrosis of the anterior abdominal wall, 3% radiation cystitis, and 3% radiation proctitis.

![]() Adelson et al. showed that this regimen is also effective for women with ovarian cancer [11]. They treated 42 women (26 single fractions, 8 with 2 fractions, and 8 with 3 fractions) and evaluated the women after each treatment.

Adelson et al. showed that this regimen is also effective for women with ovarian cancer [11]. They treated 42 women (26 single fractions, 8 with 2 fractions, and 8 with 3 fractions) and evaluated the women after each treatment.

– The patients who were evaluable at follow-up had high rates of bleeding cessation in 71.4%, decreased pain in 55%, and tumor size reduction in 75%.

– However, treatment durability was not evaluated as the median survival from the start of RT was only 5.1 months. Late GI and GU toxicity was high (23%) and the authors concluded, similarly, that 2 fractions ×10 Gy is the best and safest fractionation for effective palliation.

![]() In general, this treatment is convenient and effective for relief of pelvic symptoms from gynecologic malignancies.

In general, this treatment is convenient and effective for relief of pelvic symptoms from gynecologic malignancies.

![]() The studies show excellent rates of relief of vaginal bleeding as well as some benefit, although less, with vaginal discharge and pelvic pain.

The studies show excellent rates of relief of vaginal bleeding as well as some benefit, although less, with vaginal discharge and pelvic pain.

![]() The treatment can be given as a single fraction with reevaluation for a second and even third fraction at 4-week intervals if the patient has a reasonable performance status and may continue to benefit from therapy.

The treatment can be given as a single fraction with reevaluation for a second and even third fraction at 4-week intervals if the patient has a reasonable performance status and may continue to benefit from therapy.

![]() It has minimal acute toxicities, but does have high rates of late toxicity, especially gastrointestinal and is therefore generally reserved for patients with life expectancy <1 year.

It has minimal acute toxicities, but does have high rates of late toxicity, especially gastrointestinal and is therefore generally reserved for patients with life expectancy <1 year.

Quad Shot

• After high rates of late GI toxicity were shown in RTOG 7905, RTOG 8502 was opened with a goal to minimize late toxicity and utilized multiple daily fractions of palliative radiotherapy.

![]() The dose used was 3.7 Gy×4 fractions given over 2 days with BID treatments for a total dose of 14.8 Gy and could be repeated at 3–6 week intervals up to 3 times for a total dose of 44.4 Gy.

The dose used was 3.7 Gy×4 fractions given over 2 days with BID treatments for a total dose of 14.8 Gy and could be repeated at 3–6 week intervals up to 3 times for a total dose of 44.4 Gy.

![]() The initial Phase II protocol studied 142 patients (40% gynecologic) and showed 32% complete or partial remission of disease, 45% in patients who received all three courses, with minimal acute and late toxicity (one patient with each) [12] RTOG 8502 subsequently enrolled a second group of patients using the same treatment regimen, but randomized to either a 2- or 4-week interval between repeat courses of treatment and showed no difference in outcome [13].

The initial Phase II protocol studied 142 patients (40% gynecologic) and showed 32% complete or partial remission of disease, 45% in patients who received all three courses, with minimal acute and late toxicity (one patient with each) [12] RTOG 8502 subsequently enrolled a second group of patients using the same treatment regimen, but randomized to either a 2- or 4-week interval between repeat courses of treatment and showed no difference in outcome [13].

![]() At the completion of the three course regimen, bleeding/obstruction were completely or partially palliated in 98% patients and pain in 68%.

At the completion of the three course regimen, bleeding/obstruction were completely or partially palliated in 98% patients and pain in 68%.

![]() There is not a discussion of the durability of the results, but similarly to the patients in the 10 Gy studies, the median survival of all patients was 5–6 months.

There is not a discussion of the durability of the results, but similarly to the patients in the 10 Gy studies, the median survival of all patients was 5–6 months.

• In all, 61 patients with cervical cancer were enrolled in RTOG 8502 and had equivalent response rates to single large fraction RT, but with less toxicity [14]. More recently, Caravatta et al. escalated the dose per fraction with modern planning techniques from 3.5 to 4.5 Gy to a total dose of 18 Gy over 2 days [15].

![]() The primary evaluation of palliative response was performed with clinical evaluation at 15 days posttreatment and then subsequently every 2 months.

The primary evaluation of palliative response was performed with clinical evaluation at 15 days posttreatment and then subsequently every 2 months.

• Overall, there was an 89% complete or partial symptom remission with a median duration of palliation of 5 months (range 1–12 months) and no late toxicities.

![]() In summary, the Quad shot is convenient and effective for vaginal bleeding, obstruction, and pain. There are minimal acute and late toxicities and this regimen can be used for patients with life expectancies >6 months and even >1 year.

In summary, the Quad shot is convenient and effective for vaginal bleeding, obstruction, and pain. There are minimal acute and late toxicities and this regimen can be used for patients with life expectancies >6 months and even >1 year.

Other Palliative External Beam Regimens

• Yan et al. from Princess Margaret Hospital published a 3 fraction regimen of 18–24 Gy total dose given on days 0, 7, and 21 [16].

![]() From 1998 to 2008 they treated 51 patients with incurable gynecologic cancers, life expectancy <1 year or unable to follow intense treatment regimens due to severe comorbidities.

From 1998 to 2008 they treated 51 patients with incurable gynecologic cancers, life expectancy <1 year or unable to follow intense treatment regimens due to severe comorbidities.

![]() With a median follow up of 1.4 months, vaginal bleeding improved in 92% and pain improved completely or partially in 76%.

With a median follow up of 1.4 months, vaginal bleeding improved in 92% and pain improved completely or partially in 76%.

![]() Most of the acute toxicity was gastrointestinal (10/33 patients with data) and included grade 1–2 diarrhea, proctitis, abdominal pain, and nausea.

Most of the acute toxicity was gastrointestinal (10/33 patients with data) and included grade 1–2 diarrhea, proctitis, abdominal pain, and nausea.

![]() A benefit of this regimen is that it is a short treatment program, but allows a break between fractions for evaluation of response and patient performance status prior to proceeding with each treatment.

A benefit of this regimen is that it is a short treatment program, but allows a break between fractions for evaluation of response and patient performance status prior to proceeding with each treatment.

• In ovarian cancer, 35 Gy in 14 fractions has also been used with good durable palliation [17]. The median duration of palliation was 4 months with 90% of patients palliated until time of death, 90% vaginal bleeding control, 85% rectal bleeding control, and 83% pain relief.

• For women with bleeding at the time of diagnosis of a gynecological primary, but for whom definitive management is a consideration, it is reasonable to start with 1–2 larger fractions of external beam radiotherapy prior to definitive management. It is best to start with something like 4 Gy×1 or 4 Gy×2 so as to allow for definitive doses while respecting doses to organs at risk (OARs).

Electron Cone and Brachytherapy

• In the early part of the 1900s transvaginal electron cone therapy was used as part of definitive therapy for cervical cancers and sometimes as part of palliative therapy for vaginal bleeding, giving 5–8 Gy/day directly to the cervical mass [18,19].

• Brachytherapy has been shown to be effective at palliating vaginal bleeding from cervical cancer prior to more definitive treatment using an intracavitary cervical ring applicator [20].

![]() This was demonstrated in 15 women with stage IB2-IVB disease using 2 fractions of 5 Gy given 5–7 days apart and prescribed to the applicator surface. Complete or partial response of vaginal bleeding was shown in 93% of patients. Due to the intrinsically invasive nature of brachytherapy, it is rarely used in the palliative setting, but when prescribed to the applicator surface, can be used to stop vaginal bleeding prior to a more definitive course of therapy as it adds minimal additional dose to the OAR.

This was demonstrated in 15 women with stage IB2-IVB disease using 2 fractions of 5 Gy given 5–7 days apart and prescribed to the applicator surface. Complete or partial response of vaginal bleeding was shown in 93% of patients. Due to the intrinsically invasive nature of brachytherapy, it is rarely used in the palliative setting, but when prescribed to the applicator surface, can be used to stop vaginal bleeding prior to a more definitive course of therapy as it adds minimal additional dose to the OAR.

Recurrent Disease

• In patients who have not had prior pelvic RT, the above options are all reasonable, depending on assessment of performance status and life expectancy.

• In patients who have received prior RT to the pelvis, re-irradiation may be given to smaller areas with careful field design to limit dose in regions of prior treatment [1]. With longer intervals between courses of radiation, there may be some recovery of the normal tissues, but in general, re-irradiation after prior definitive doses should be reserved for patients with limited life expectancies due to the concerns for increased late toxicities. The primary OARs in the pelvis are the bladder, rectum, bowel, and femoral heads. The Quantitative Analyses of Normal Tissue Effects in the Clinic (QUANTEC) data can be used as a general guideline for determining the risk of toxicity to these structures with additional pelvic radiotherapy [21–23]. However, further caution should be used in patients who were treated with hypofractionation or brachytherapy, as the QUANTEC data is based on conventional fractionation. The ABS worksheets can be helpful as a reference for converting brachytherapy doses into the radiobiologic equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2) as well as giving an associated biologic equivalent dose (BED) for late effects [24].

Primary Genitourinary Malignancies

• Published literature regarding high-dose single fraction RT for primary GU malignancies is almost nonexistent.

• In RTOG 7905 only two patients had primary tumors arising from the prostate. The majority of the published regimens vary from a short hypofractionated scheme to a more conventional 2–3 week course of treatment.

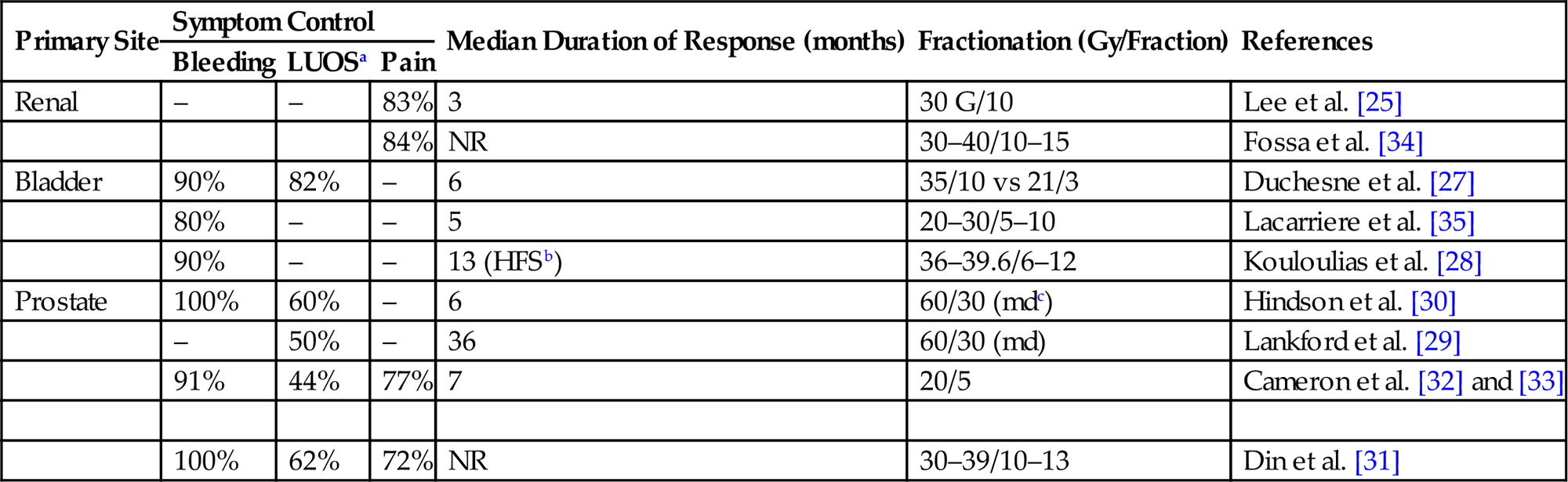

• Unlike the GYN literature, the GU series report results separated by primary of origin rather than by dose fractionation scheme. Table 16.2 summarizes dose and fractionation schemes for GU malignancies by primary site.

Table 16.2

Summary of Dose and Fractionation of Palliative Regimens for Genitourinary (GU) Malignancies

| Primary Site | Symptom Control | Median Duration of Response (months) | Fractionation (Gy/Fraction) | References | ||

| Bleeding | LUOSa | Pain | ||||

| Renal | – | – | 83% | 3 | 30 G/10 | Lee et al. [25] |

| 84% | NR | 30–40/10–15 | Fossa et al. [34] | |||

| Bladder | 90% | 82% | – | 6 | 35/10 vs 21/3 | Duchesne et al. [27] |

| 80% | – | – | 5 | 20–30/5–10 | Lacarriere et al. [35] | |

| 90% | – | – | 13 (HFSb) | 36–39.6/6–12 | Kouloulias et al. [28] | |

| Prostate | 100% | 60% | – | 6 | 60/30 (mdc) | Hindson et al. [30] |

| – | 50% | – | 36 | 60/30 (md) | Lankford et al. [29] | |

| 91% | 44% | 77% | 7 | 20/5 | Cameron et al. [32] and [33] | |

| 100% | 62% | 72% | NR | 30–39/10–13 | Din et al. [31] | |

aLUOS, Lower Urinary Obstructive Symptoms.

bHematuria Free Survival.

cMedian Dose.

Renal Cell Carcinoma

• Although renal cell carcinoma has been regarded as a relatively radio-resistant malignancy, worthwhile palliative response can be achieved in the metastatic setting with conventional palliative regimes.

• Lee et al. demonstrated good pain control from bony metastatic disease by delivering of 30 Gy in 10 fractions with 83% of patients reporting site-specific pain relief after treatment and a median duration of site-specific pain response of 3 months (range, 1–15 months) [25].

• The emergence of extracranial stereotactic RT prompted its use in metastatic and primary inoperable renal cell carcinoma. The group at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden reported the outcomes of 58 patients with either metastatic or primary nonoperable renal cell carcinoma with total number of treated metastatic sites being 162.

![]() Over 70% of the metastatic sites were in the lungs but 8 patients had primary inoperable malignancies and 12 had metastasis to the remaining kidney.

Over 70% of the metastatic sites were in the lungs but 8 patients had primary inoperable malignancies and 12 had metastasis to the remaining kidney.

![]() Most common dose-fractionations schedules were 32–40 Gy delivered in 4 fractions and 45 Gy in 3 fractions all through the course of approximately 1 week.

Most common dose-fractionations schedules were 32–40 Gy delivered in 4 fractions and 45 Gy in 3 fractions all through the course of approximately 1 week.

![]() Local control rate was >90% with complete tumor regression in 30%. For the eight patients that had an inoperable primary tumor five were alive with no recurrence and symptom free at 4 years [26].

Local control rate was >90% with complete tumor regression in 30%. For the eight patients that had an inoperable primary tumor five were alive with no recurrence and symptom free at 4 years [26].

Bladder Cancer

• The first trial of palliative radiotherapy in tumors arising from the bladder was published over 15 years ago and consequently used relatively simple radiation treatment techniques.

• Patients with symptomatic, muscle invasive bladder cancer, unsuitable for surgical resection, chemotherapy, or definitive radiation treatment were randomized between two fractionation regimens.

![]() A standard arm of 35 Gy in 10 fractions was compared to 21 Gy delivered in 3 fractions in 1 week.

A standard arm of 35 Gy in 10 fractions was compared to 21 Gy delivered in 3 fractions in 1 week.

![]() At the end of treatment 50% of the patients in each arm had noticed significant improvement in their symptoms (the most common symptoms being urinary frequency and hematuria).

At the end of treatment 50% of the patients in each arm had noticed significant improvement in their symptoms (the most common symptoms being urinary frequency and hematuria).

![]() At 3 months overall improvement in hematuria, urinary frequency, and dysuria was 90%, 82%, and 72%, respectively, with no difference among either treatment regimen.

At 3 months overall improvement in hematuria, urinary frequency, and dysuria was 90%, 82%, and 72%, respectively, with no difference among either treatment regimen.

![]() Median time to symptom progression after response was 6 months with a median survival of 7.5 months [27].

Median time to symptom progression after response was 6 months with a median survival of 7.5 months [27].

• More recently Kouloulias et al. [28], published a large retrospective review using weekly radiation doses between 5.75 Gy and 6 Gy for 5–6 weeks in patients with advanced bladder cancer with hematuria and pelvic pain.

![]() The authors reported resolution of the hematuria in 90% and 95% of the patients, respectively, with grade 3 or higher acute urinary toxicity between 0% and 9%.

The authors reported resolution of the hematuria in 90% and 95% of the patients, respectively, with grade 3 or higher acute urinary toxicity between 0% and 9%.

![]() Median survival ranged between 10 and 14 months, with a mean hematuria free survival of 13 months, which suggests that simple interventions can provide long-lasting meaningful palliative responses

Median survival ranged between 10 and 14 months, with a mean hematuria free survival of 13 months, which suggests that simple interventions can provide long-lasting meaningful palliative responses

Prostate Cancer

• The management of advanced incurable locally symptomatic prostate cancer is quite challenging. Multiple fractionation schemes have been reported, ranging from long courses of 60 Gy in 30 fractions to shorter hypofractionated schemas such as 20 Gy in 5 fractions and the “quad shot” regimen.

• The group at M.D. Anderson Cancer Center reported in 1997 their experience with long courses of palliative RT for locally advanced symptomatic hormone ablation refractory prostate cancer.

![]() A total of 29 patients received a mean dose of 60.4 Gy (10–80.2 Gy) using mainly photons.

A total of 29 patients received a mean dose of 60.4 Gy (10–80.2 Gy) using mainly photons.

![]() More than half of the patients were treated due to obstructive urinary symptoms and a third were treated following progression on digital rectal exam with or without symptoms.

More than half of the patients were treated due to obstructive urinary symptoms and a third were treated following progression on digital rectal exam with or without symptoms.

![]() The 4-year local control, defined as the absence of new or progressive urinary obstructive symptoms, new or progressive disease on DRE, or biopsy confirmation of local active disease was 61% with the majority of the patients remaining symptom free. The majority of the failures were distant.

The 4-year local control, defined as the absence of new or progressive urinary obstructive symptoms, new or progressive disease on DRE, or biopsy confirmation of local active disease was 61% with the majority of the patients remaining symptom free. The majority of the failures were distant.

![]() Interestingly, patients treated to a dose >60 Gy had a local control of 90% compared to 29% for those receiving less than 60 Gy [29].

Interestingly, patients treated to a dose >60 Gy had a local control of 90% compared to 29% for those receiving less than 60 Gy [29].

• Hindson et al. in 2007 reported on 35 patients with advanced symptomatic (hematuria, bladder outlet obstruction or rectal obstruction) hormone refractory prostate cancer that received 60 Gy at 2–3 Gy per fraction.

![]() Overall response rate was about 60% with patients presenting with more than one symptom reporting a higher response rate of 83%.

Overall response rate was about 60% with patients presenting with more than one symptom reporting a higher response rate of 83%.

![]() Bladder outlet and rectal obstruction showed a partial response in 18 patients with no complete responders, but all of them continued to show partial improvement at 6 months.

Bladder outlet and rectal obstruction showed a partial response in 18 patients with no complete responders, but all of them continued to show partial improvement at 6 months.

![]() Of the five patients presenting with hematuria alone, three maintained a complete response 6 months posttreatment. Median survival was 13.7 months; they did not find any dose–response correlation [30].

Of the five patients presenting with hematuria alone, three maintained a complete response 6 months posttreatment. Median survival was 13.7 months; they did not find any dose–response correlation [30].

• Additional data regarding less protracted regimens has become available in the past few years, as 25% of the patients enrolled in RTOG 8502 (discussed previously) had primary tumors arising from the GU tract, suggesting the efficacy of such fractionation in this population.

• More recently, Din et al. from the United Kingdom retrospectively analyzed their experience in 58 men with symptomatic locally advanced prostate cancer using simple fluoroscopic simulation with an opposed APPA (10×10) beam arrangement with the center of the field at the superior edge of the symphysis pubis.

![]() Patients received 20 Gy delivered in 5 daily fractions.

Patients received 20 Gy delivered in 5 daily fractions.

![]() Overall response rate at 4 months was 89%. Response rate at 6 weeks, 4 months, and 7 months for hematuria was 81%, 42%, and 29%, respectively.

Overall response rate at 4 months was 89%. Response rate at 6 weeks, 4 months, and 7 months for hematuria was 81%, 42%, and 29%, respectively.

![]() Urinary outflow obstruction improvement was seen in two-thirds of the population with more than half of them maintaining this response at 7 months.

Urinary outflow obstruction improvement was seen in two-thirds of the population with more than half of them maintaining this response at 7 months.

![]() Pain response was above 60% in the first 4 months but dropped to 38% at 7 months, suggesting progression of disease [31].

Pain response was above 60% in the first 4 months but dropped to 38% at 7 months, suggesting progression of disease [31].

• A systematic review of published trials on palliative pelvic radiotherapy for symptomatic incurable prostate cancer listed nine studies (all retrospectives chart reviews) with total doses and fraction sizes varying from 8 to 78 Gy and 2 to 8 Gy, respectively.

![]() All nine studies had pre- and posttreatment quality of life assessment.

All nine studies had pre- and posttreatment quality of life assessment.

![]() The overall symptom response rate was 75% with response rates for hematuria, pain, bladder outlet obstruction, rectal discomfort, and ureteric obstruction of 73%, 80%, 63%, 78%, and 62%, respectively [32].

The overall symptom response rate was 75% with response rates for hematuria, pain, bladder outlet obstruction, rectal discomfort, and ureteric obstruction of 73%, 80%, 63%, 78%, and 62%, respectively [32].

• More recently the group at Oslo University Hospital in Norway published the results on 47 men with symptomatic incurable prostate cancer. This was a prospective multicenter study that looked at patient-reported outcome over a target symptom identified by the patient as the main problem.

![]() Patients received 30–39 Gy in 10–13 daily fractions.

Patients received 30–39 Gy in 10–13 daily fractions.

![]() Almost 50% had lower urinary obstructive symptoms, with 25% complaining of hematuria and 20% of pelvic pain. Symptoms were assessed at baseline and 12 weeks after treatment.

Almost 50% had lower urinary obstructive symptoms, with 25% complaining of hematuria and 20% of pelvic pain. Symptoms were assessed at baseline and 12 weeks after treatment.

![]() Improvement or complete resolution of the target symptom was achieved in 62%, 80%, and 72% of the patients at the end of radiotherapy, after 6 weeks, and at 12 weeks, respectively.

Improvement or complete resolution of the target symptom was achieved in 62%, 80%, and 72% of the patients at the end of radiotherapy, after 6 weeks, and at 12 weeks, respectively.

![]() It is important to mention that at 12 weeks there was a 100% response rate for hematuria with lower urinary obstruction symptom relief seen in 8 out of 18 patients and only 1 patient reporting worsening symptoms.

It is important to mention that at 12 weeks there was a 100% response rate for hematuria with lower urinary obstruction symptom relief seen in 8 out of 18 patients and only 1 patient reporting worsening symptoms.

Mild to moderate diarrhea was the most common toxicity with no grade 4 complications seen [33].

Penile and Urethral Cancer

• Locally advanced incurable urethral and penile carcinomas can cause significant symptoms from urinary obstructive symptoms to pain and hematuria as well as severe emotional distress.

• Palliative RT is commonly used in these scenarios to help relief some of the aforementioned symptoms.

• Common regimens include 30 Gy in 10 daily fractions as well as slightly more protracted 45 Gy in 15 fractions when there is no evidence of metastatic disease in the hopes to maintain a longer duration of response.

• Because of the rare occurrence of these tumors there is a lack of published data when definitive treatment is not possible with most of the clinical practice being extrapolated from experiences in other GU and gynecological sites.

Treatment Planning

• Treatment planning should be as simple as possible.

• Patients are supine with arms at sides (if treating AP/PA) or on chest /overhead for four-field technique.

• No need for custom immobilization or contrast in most cases.

• For tumors extending into the vagina it can be helpful to mark the lowest extent of disease with a gold fiducial marker, radiopaque vaginal packing or a BB.

• Gross tumor volume should be contoured and then fields designed with at least 2 cm to beam edge (Fig. 16.1A). Symptomatic patients may have difficulty holding still, so generous margins are essential to ensure adequate tumor coverage in many cases.

• Most simple field design is AP/PA, but increased homogeneity with four-field.

• For patients treated emergently 2D planning or clinical setup may be used. In that case a standard 15×15 cm pelvic field AP/PA is typically used (Fig. 16.1B).

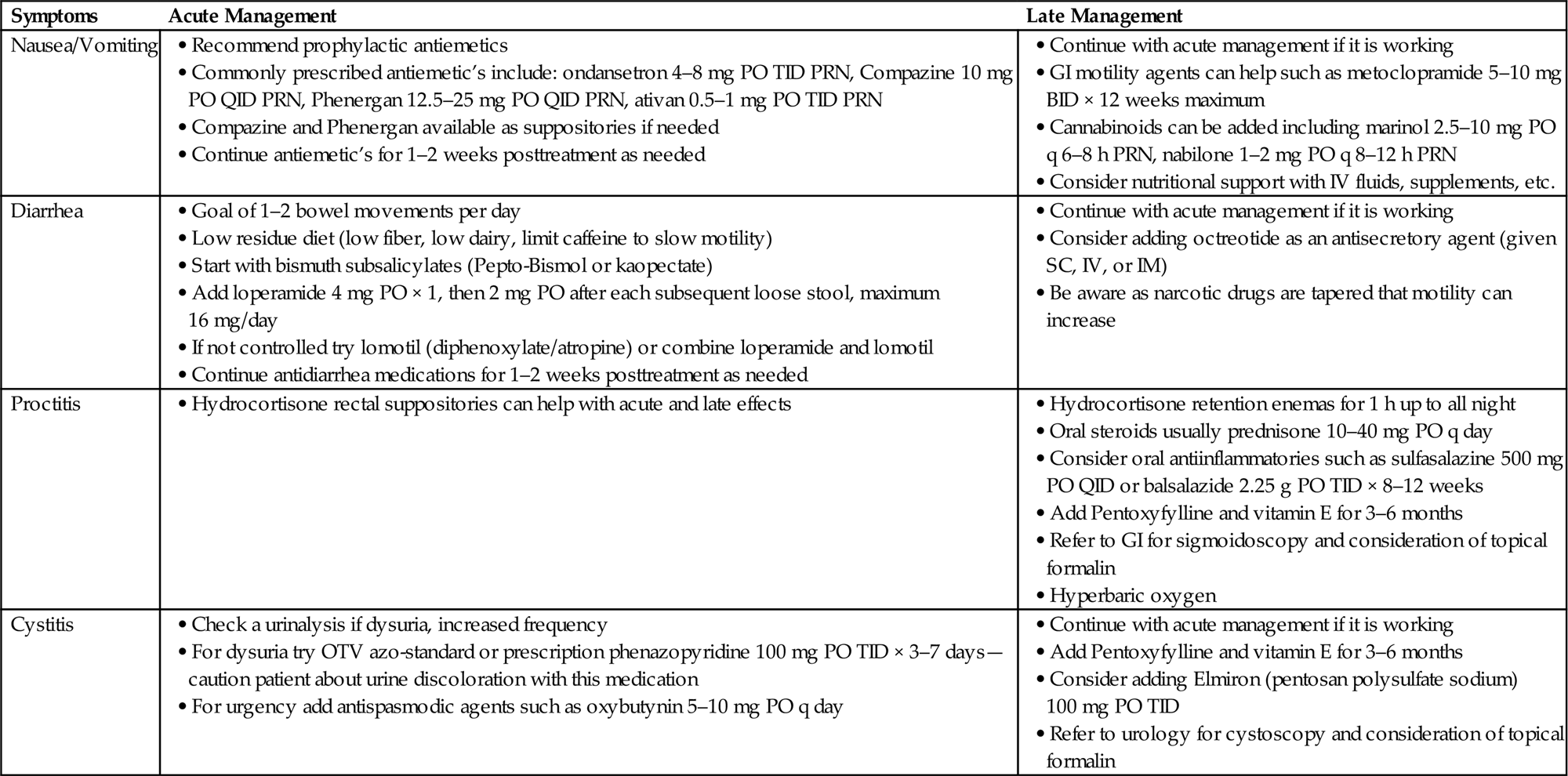

• Table 16.3 details acute and late management for on-treatment issues seen during treatment of both GU and GYN malignancies.

Table 16.3

Conclusion

Radiotherapy is effective in the palliation of many symptoms of advanced gynecologic and GU malignancies. It spares these patients from morbid pelvic surgeries and may delay more toxic systemic therapy.

Although technology is advancing and we are capable of performing more conformal and higher dose treatments, some of the older and simpler techniques and fractionation schedules may in fact be the most effective with the least long-term toxicities. In general, short courses of treatment are preferable and may be able to provide reasonable durability of symptom control with minimal time commitment and low rates of toxicities. The particular treatment regimen may be tailored to the individual patient by considering specifics such as the expected outcome (palliative vs definitive), expected duration of symptom control (short-term vs more durable), and whether side effects will be tolerated. Other considerations include patient performance status, life expectancy, prior treatments, and patient convenience.

List of Abbreviations

ABS American Brachytherapy Society