CHAPTER 6

Understanding Hardiness-Control

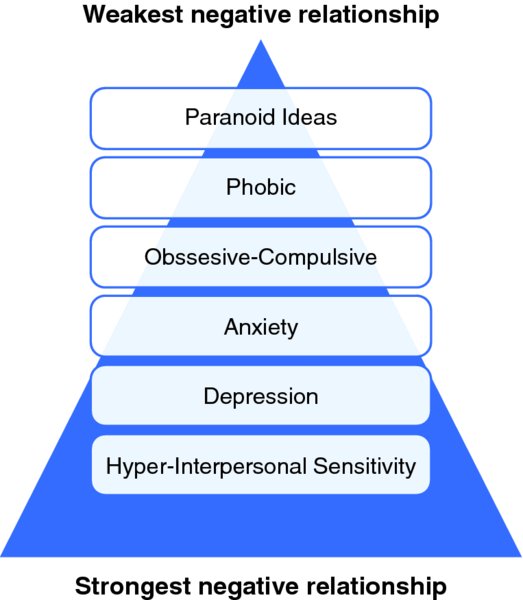

“Ultimately, the only power to which man should aspire is that which he exercises over himself.” —Elie Wiesel (Writer, professor, Nobel Laureate, Holocaust survivor) How much do you feel you are in control of events around you? Do you believe the world is getting out of control and there is little anyone can do to change things? Or do you feel there is a piece of the world where you have a good sense of control? Where we see ourselves and our sense of control over the things around us plays an important role in our ability to overcome the challenges that we encounter in life. The control part of the hardiness model involves a strong belief that you can influence outcomes in your life, and you are willing to make choices and accept responsibility for those choices. It captures how much in control you feel of your destiny, despite the uncertainty that is often associated with the future. People who have a strong sense of control tend to approach new situations with confidence because they believe that they can influence the results. Researchers have long recognized that people generally want control, and it is to their benefit for an individual to feel like they are in control of situations that are occurring. Feeling in control allows you to think that you can safely and effectively manage your environment and life circumstances, even when stressful situations come your way. Michael J. Fox is a well-known actor, comedian, author, and film producer. He starred in films and TV shows such as Back to The Future, Spin City, and Family Ties. His work won him a number of awards including five Primetime Emmy Awards, four Golden Globe Awards, a Grammy Award, and two Screen Actors Guild Awards. At the age of 29, Fox was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. He didn’t disclose his condition until seven years later. After getting the news from his doctor, Fox started to drink heavily and live recklessly. He was basically in a state of denial about the disease. He eventually got help for his drinking and stopped altogether (Brockes, 2009). It would have been easy for Fox to simply give up, retreat, and stay at home with his family. He certainly had the money to quit and retire. He could have either kept on denying his disease or simply accepted that things like this just happen “for a reason.” Instead, he admitted his plight and became a huge activist and advocate on behalf of sufferers of Parkinson’s disease. He testified before a Senate Appropriations Subcommittee, campaigned for a politician supporting stem cell research, raised funds, and spoke out on numerous platforms. He took control of the direction of his life, in spite of his physical limitations. At one point, things got even worse for Fox. He started falling. He underwent a medical examination and learned that he had an additional problem with his spinal cord that required surgery. After the operation and some intense physical therapy, he started feeling better, even though he hadn’t yet fully recovered. He started taking extra risks and one day he took a misstep, fell, and fractured his arm. His response about the incident gives us a bit more insight into his use of hardiness-control. He stated, “I try not to get too ‘New Age-y.’ I don’t talk about things being ‘for a reason.’ But I do think the more unexpected something is, the more there is to learn from it. In my case, what was it that made me skip down the hallway to the kitchen thinking I was fine when I’d been in a wheelchair six months earlier? It’s because I had certain optimistic expectations of myself, and I’d had results to bear out those expectations, but I’d had failures too. And I hadn’t given the failures equal weight” (Marchese, 2019). We see that people high in control don’t believe they can conquer all the obstacles in their way. They realize they have limitations and learn from their experience. This sets hardiness apart from another popular concept known as “grit” (Duckworth, 2016). People with high grit are more likely to keep forging ahead, persisting even when the goal is unreasonable or unattainable. Hardiness-control, on the other hand, involves understanding your limits and knowing when to push and when to pull back. There has been a lot of research on self-control and how it impacts us. For example, studies have shown that people higher in self- control do better academically at school, have happier interpersonal relationships, commit less crime, are less involved in drug use, and are less aggressive (DeWall, Finkel, & Denson, 2011; Packer, Best, Day, & Wood, 2009; Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004). However, there is a major misunderstanding about what is actually meant by self-control. It’s not just a matter of willpower or inner resources to overcome temptations. The research has found that people high in self-control are more likely to develop healthy habits and avoid temptations—as opposed to just fighting them. For example, a person with an alcohol problem who has high self-control may just skip that tempting invitation to a tailgate party before the game. On the other hand, the low self-control alcoholic may go along to the party hoping to fight the urge to drink. In an interesting series of studies, a group of researchers at Texas A&M University looked at self-control in relation to what is termed visceral states (Baldwin, Finley, Garrison, Crowell, & Schmeichel, 2018). Visceral states are basically the internal physiological conditions you are in when motivated to act. These include drives such as hunger and thirst. It is when these drives or visceral states are high, such as when you’re hungry, that you are motivated to eat, thus breaking your diet. Or when you are sleep deprived you tend to eat more high-calorie foods. Being under stress has been found to reduce people’s control, causing them to eat tastier and less healthy items. Having a minor illness, such as a cold, has been associated with fatigue, malaise, and pain in people under stress. Self-control is associated with the effective use of healthy habits. It is when your visceral states, such as hunger and thirst, get more intense that your ability to control your habits is challenged. The higher your control, the better able you are to resist unhealthy behaviors. For example, by eating more frequently, higher control people are then less tempted to overeat and to choose unhealthier foods. The Texas A&M researchers looked at these habits in 5,598 undergraduate college students who were subjects in their labs. They measured the students’ levels of control as well as their visceral states across a number of different conditions and studies over a five-year period. Their findings showed that people who were higher in self-control experienced less intense and a lower presence of visceral states. In other words, people who scored higher in measures of self-control showed lower levels of hunger and fatigue, lower prevalence of common colds, and less extreme stress. Once again, higher control is related to lower presence and lower intensity of visceral states. Additional research with this group uncovered more about the relationship between higher self-control and healthier habits, which, of course, leads to healthier lifestyles. The researchers found that people with higher self-control were less hungry when they were tested, partly because they ate more recently. They also had less fatigue at the time they were seen for the study because they reported having slept more the previous night. This research helps us better understand why people higher in control have consistently been found to be healthier. We’re also learning that higher control is associated with having an inclination for orderliness, planning, and thinking ahead. Some of these qualities sound very much like the personality trait of conscientiousness. The high self-control person is likely to plan out vacation times carefully, picking the best choice in hotels, knowing which route they will take to get there, making dinner reservations in advance, and pre-purchasing event tickets. The low self-control person is more likely to wing it, possibly getting lost along the way, having to spend time and money finding a decent hotel with a vacancy, searching last minute for things to do, and perhaps discovering that the concert they wanted to see is already sold out. Research in the field of personality has shown that high conscientiousness is also associated with living more healthily and experiencing less stress. So, where then does conscientiousness come from? There is no simple, complete answer as yet, but we do know the trait is partly inherited and that it is fostered through having meaningful social roles and responsibilities. Self-control, in addition to influencing orderliness and planning, is also related to intelligence. Some aspects of intelligence, such as rote memory, are more automatic and likely not influenced by control. Other aspects, however, such as logical reasoning and extrapolation (using both reasoning and elaborating on results), have been found to be affected by self-control (Schmeichel, Vohs, & Baumeister, 2003). While we’ve presented some of the benefits of having a strong sense of hardiness-control, there has been some disagreement among psychologists about whether or not you can have too much control. We tend to think of the benefits of high levels of self-control helping us with impulsive behaviors, such as dieting and smoking. It turns out that these are the most difficult kinds of behaviors to control. If they were easy to control, we wouldn’t see huge industries developed to try to manage these behaviors. Unfortunately, the research in this area, using follow-up studies, does not find much success in controlling these kinds of behaviors through sheer will power or any amount of consciously trying to manage them. There’s a lot of evidence that high levels of control or delay of gratification—also referred to as impulse control—are related to higher grades in school. People higher in control are more disciplined and better able to plan and set aside time for doing homework and studying. Procrastination is highly related to low self-control. High procrastinators are easily distracted and sidetracked from tasks. Instead of doing their online research for a school paper or work project, they’re more likely to get caught up in gossip, shopping, or travel websites. You may be familiar with the famous “marshmallow test” carried out by Walter Mischel at Stanford University in the 1960s. Mischel’s experiment involved a number of four-year-old children. Each child was seated in a room that contained a chair, a table, and a single marshmallow. The experimenter informed the child that he or she had to run an errand, and made the child an offer. If the child wanted to eat the marshmallow immediately, that would be okay. But if the child waited until the adult returned, the reward would be a second marshmallow. The kids made their choices. Two-thirds of them managed to hang tough and earn the second marshmallow. The rest did not. Mischel was able to locate them twelve and fourteen years later, when they were about to graduate from high school. At this point, he gained access to their academic records and asked their parents to evaluate how successful they had been in and out of school. The kids who had gobbled up the first marshmallow, not waiting for the second, were reported as having one or two problems. As a group, they were less adept at making social contacts and more prone to being stubborn and indecisive. They yielded readily to frustration as well as temptation. Those who had put their gratification on hold—and by doing so, doubled their pleasure with a second marshmallow—were more successful. They showed more social skills, exhibited superior coping mechanisms, and, in general, were ahead of the game. This was reflected in their grades. They were, simply put, better students and had scored remarkably higher on the SAT. It sounds incredible—but the ability, at age four, to wait for a second marshmallow was two times more accurate a predictor of a kid’s future SAT score than was his or her IQ (Shoda, Mischel, & Peake, 1990; Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989). A second area where researchers have found a strong connection with self-control is with impulse control problems such as binge eating and alcohol abuse. There have been a number of different studies linking low control with problem drinking. In addition, people low in control have been found to have more problems in saving money, and a higher incidence of eating disorder problems. People low in control have been found to have more adjustment problems. These include a number of mental health disorders. For some disorders this may seem obvious, such as depression and anxiety. These are perceived as problems that involve lack of emotional control. However, other disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder and anorexia nervosa, are seen as problems where there may be too much control or overcontrol. There is at least one study that shows higher self-control is related to being more mentally healthy in all of the areas that were measured (Tangney et al., 2004). These included somatization (the expression of mental stress through physical symptoms), obsessive-compulsive patterns, depression, anxiety, anger, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideas, and psychoticism. Rather than thinking of disorders such as obsessive- compulsiveness as “overcontrol,” these researchers describe them as problems in self-regulation. In other words, people with these types of problems have difficulty in regulating their emotions. So, having a higher level of control means being able to better control or regulate your emotions and impulses, and being less obsessive-compulsive or less perfectionistic. We carried out our own research looking at the relationship between hardiness-control (along with the other hardiness factors) and a number of mental health challenges as measured by the validated screening tool, the SA-45 or Symptom Assessment 45. This measure is used by hundreds of medical and mental health centers to screen tens of thousands of patients every year (Maruish, 2004). We surveyed 332 working adults with the Hardiness Resilience Gauge and the SA-45 and looked at the relationships between the presence of mental health symptoms and hardiness. Our results paralleled the previously cited research in that the higher someone’s hardiness and hardiness control, the lower their overall symptom scores. In fact, the higher the control score, the significantly lower the symptom scores, with the strengths of the relationships shown in Figure 6.1. Figure 6.1 Hardiness Control and Significantly Related Mental Health Issues So, the strongest negative relationship is between hardiness-control and interpersonal sensitivity (being overly sensitive to others). The higher your hardiness control, the lower your interpersonal sensitivity, or the better your ability to get along with people. Also significant, but not quite as strong, is the link between hardiness-control and paranoid thinking. What’s really interesting here is the negative relationship between hardiness-control and obsessive-compulsiveness. This has been one of the concerns of researchers in this area as previously mentioned. Can too much control lead to perfectionism or obsessiveness? Our data, just like the previously reported study, doesn’t support that. It seems that people high in hardiness- control are better able to control their impulses, whereas people who are overly perfectionistic or obsessive are not able to regulate their emotions and impulses well. There were three symptom areas where we did not find a significant connection with hardiness control. These were somatization (having physical symptoms, likely due to psychological reasons), hostility, and psychoticism (having unusual thoughts, hearing things, seeing things that others don’t experience). So, regardless of a person’s hardiness-control score, they can have physical symptoms, be mean to others, or have unusual thinking patterns. What are some of the positive effects of higher self-control? One study looking at control in the workplace found that supervisors with higher self-control were more trusted by their subordinates. They also received higher ratings of fairness (Cox, 2000). Max was a manager at a large box manufacturing company. He was referred for coaching by Alice, a vice president of the company. Alice was getting negative feedback about Max from a number of employees who reported to him. They felt that he wasn’t treating them fairly. Alice called Max in for a talk. It became pretty clear to Alice after a brief time that Max had no idea how he came across to other people, especially those he supervised. She felt he needed some clarification about his behavior and how he was seen by others. Max’s coach gave him the Hardiness Resilience Gauge. His score in hardiness control was quite low, especially relative to his other scores. He scored higher in commitment and challenge. When asked about his control score, Max talked about his need to be liked and how he hated setting limits on others. He felt that other people were responsible enough to make their own decisions, and he didn’t like to interfere in that. “If things are going to go bad, well, that’s just the way it goes,” replied Max. “I don’t really think my intervention will change anything.” Max’s coach pointed out that people like to receive feedback on their work. Giving no feedback implies that either you don’t care, or that maybe you don’t approve of their work. Leaving people to their own devices to decipher how they are performing at work can be like driving a car without a steering wheel. Max learned about the importance of giving performance feedback to his staff when they were applying any skill, in order to improve and ensure that they are on the right track. He learned that facial expressions, such as a frown (even if involuntary), can be negatively interpreted and affect someone’s performance. There were a number of areas in Max’s life where he didn’t take initiative. His coaching led him to learn to be more responsible and responsive to the cues around him. His belief that “things happen” eventually changed to “things happen, and I may have some influence over them.” In other words, he learned to increase his hardiness-control by taking more responsibility and taking action to make things happen. Over time his subordinates saw a change in him and felt not only more comfortable, but more fairly treated as he was more consistent in his treatment towards them. In a major review of the work on control and its importance in organizations, published in the Harvard Business Review, a group of researchers summarized some of the most significant findings to date (Yam, Lian, Ferris, & Brown, 2017). While repeating some of the results we’ve already mentioned—that people higher in self-control eat healthier, are less likely to have substance abuse problems, build more quality friendships, and perform better at school—there are also some work-related findings. For example, high self-control leaders demonstrate more effective leadership styles. They are better at inspiring and intellectually challenging their followers. They tend to be less abusive of others and micromanage people less. The researchers report that self-control in the workplace is like physical fitness. You only stay fit as long as you exercise and replenish your strength. For example, they found that when self-control decreases in the workplace, more negative or bad things happen. One study found that nurses who were lower in control were more rude to their patients. Another study found that tax accountants lower in control were more likely to commit fraud. In general, it was found that employees lower in control were more likely to lie to their supervisors and steal office supplies from work than fellow employees who scored higher in control on self-assessments. There were a number of social behaviors at work that were found to be related to control as well. Employees who were lower in control were less likely to speak up when they saw problems at work. And they were less likely to help fellow employees in need. In addition, their social responsibility was lower, as they were less inclined to volunteer for corporate and other events. Finally, corporate leaders low in control were found to have a number of shortcomings. They engaged in more verbal abuse of their followers and were less likely to use positive motivators. They tended to have poorer relationships with their subordinates and were rated as less charismatic. There are also some interesting recommendations that were found to help people increase their control. One factor that made a big difference was the amount of sleep that people got. People who slept well at night—had few interruptions to their sleep—were found to have much better self-control at work and were found to be less abusive toward others. They yelled and cursed less than fellow employees who had slept poorly. Causing workers to put in extraordinary amounts of time, or even increasing people’s stress levels so that it affects their sleep time, can hurt workplace productivity. Some companies, such as Google, have even placed sleep pods at their offices in order to allow employees to nap and re-energize. Another issue that has been found to affect an employee’s sense of control is the “service with a smile” mantra that many companies sponsor. Forcing employees to smile at customers, even while being mistreated, might cause some short-term gain but can create longer-term problems in an employee’s health and in the organization. Training employees in empathy—learning to read other people’s emotions—and understanding their perspective can be a healthier approach. It doesn’t mean you have to agree or smile with each customer, or even acknowledge whether they might be right. You can let them know you understand how they feel (“I can feel your pain”), and you will do the best you can in the circumstances. It doesn’t mean pleasing every customer, but it does let the employees be honest, keep their dignity, and stay healthier. Studies with physicians have found that doctors who faked empathy reported increased burnout and lower job satisfaction. On the other hand, doctors who could engage in perspective taking—learning to see things through the other person’s eyes—and were genuinely empathic, fared much better (Larson & Yao, 2005). In an organization it’s also important to create an ethical culture. Studies have found that in organizations that promote their code of conduct—through signs in the building, in staff meetings, newsletters—there are fewer transgressions associated with lower self-control. These reminders help some people avoid temptations and keep them on the right track. While this approach has mostly been found to be effective in the short term, it can be a cost-effective way of keeping a workplace more civil. Control is a valuable approach for managing both the expected and unexpected stressors in your life. Developing a better sense of control can help you navigate many of life’s challenges. In the next chapter we’ll look at some specific strategies you can use to increase control in your life.

Taking Control When Your Body Can’t: Michael J. Fox

Managing Your Internal Drives

Planning an Orderly Future

Control: Too Much or Too Little

Managing Your Impulses

Can Mental Health Problems Be Related to Control Issues?

Can Higher Control Have Benefits at Work?

How Control Can Make You More Effective at Work

How Can You Start to Improve Your Control?