CHAPTER 1

Stress: What’s All the Fuss?

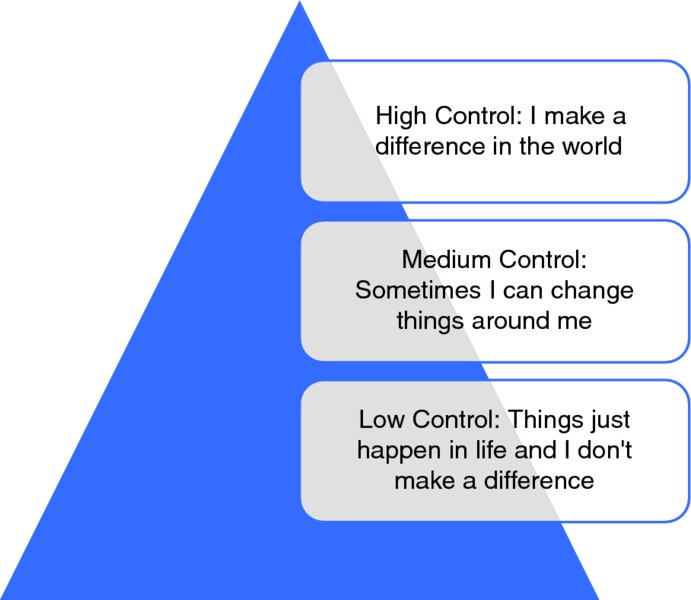

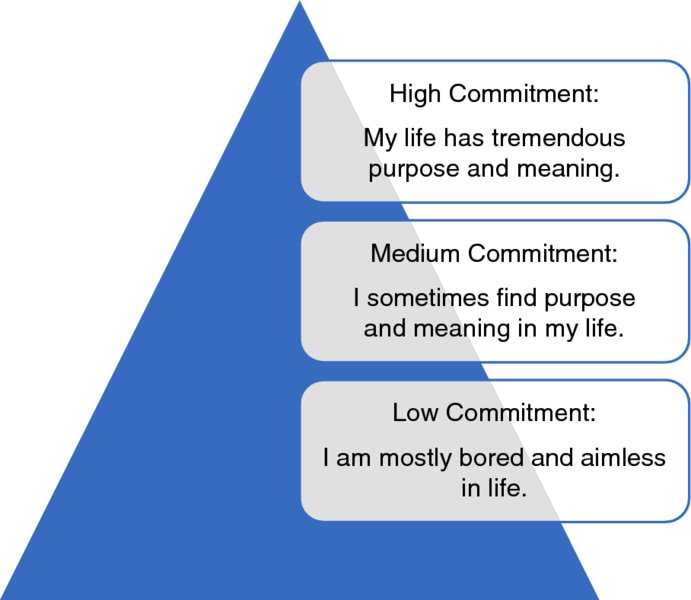

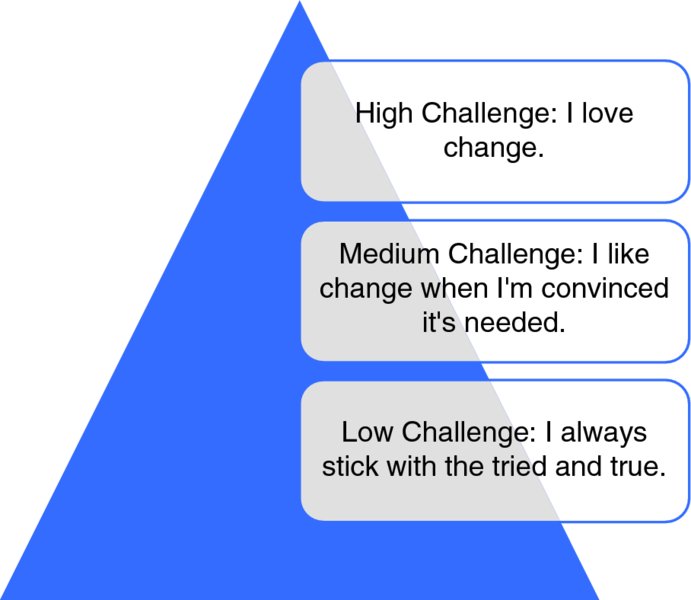

“The greatest weapon against stress is our ability to choose one thought over another.” —William James (American philosopher and psychologist) Belinda had been preparing for this day weeks in advance. Her team was counting on her to fly to their head office in New York to present their new plan for the year. It involved a substantial increase in funding and a new direction for their division that would trigger many questions from the senior managers. Belinda could justify the new plan better than anyone, as she was most responsible for putting all the pieces together. She woke up fresh and alert. She would take her kids to school on her way to the airport. She chose a flight that allowed her some relaxing time in the lounge at the airport. However, after looking out the window, she realized there was an obstacle she hadn’t considered. Her driveway was completely covered in snow, and the snow removal guy she hired hadn’t arrived yet. She suddenly felt a mild panic. Her heart started beating faster, and her face became a bit flushed. She counted to five, and then told herself she still had lots of time. “Be positive,” she thought. She could work this out. She woke her kids and got them to help her start shoveling the snow in the meantime. The snow was heavy and deep, and the clock was ticking. She hoped school would be cancelled, but unfortunately, the school district sent a text notifying parents that all the city schools were open. By the time they got the driveway half cleared, she started getting anxious again, realizing she was losing valuable time. She then decided she would back out of the driveway by putting her foot to the pedal on her SUV with a force that would get her over the unshoveled snow and onto the road. The car suddenly lurched back and got caught at the end of the driveway, with the rear barely on the road. The snow was too deep. Her rear tires started to spin. She wasn’t moving. She began to shift from reverse to forward, back and forth, stepping on the gas each time. She asked her kids to push the car, but it wouldn’t budge. They started shoveling again, then rocking the car. She was completely out of breath from shoveling and the fear of missing her flight. She felt like she might faint. After 10 minutes of panic, she didn’t know what to do. Could she leave her SUV partly on the street, should she call a cab or Uber, what next? Suddenly she jumped out of the car and looked up and down the street for snow removal trucks. Finally, she saw one turning the corner and breathlessly ran towards it, stopping the driver in the middle of the street. She asked if he’d help out by clearing the back of her driveway with his plow so she could get her car onto the road. He explained that he had dozens of driveways to clear and was already behind on his schedule. Her breathing, at this point, was so deep, she almost fell to the ground with exhaustion. She begged him, telling him she had to make it to the airport and how it was really important. He finally agreed and cleared the bottom of the driveway. With her kids pushing her back she was finally able to make it onto the road. By now she had lost almost 40 minutes. She dropped her kids off at school and took off to the airport. The highway was completely jammed as the snow caused massive traffic congestion. Sitting on the highway, she started sweating profusely. Her heart was racing once again. She had to make this plane. She finally got to the airport and decided to leave her car at the valet parking where she grabbed the ticket from the attendant and ran to the departure gates. When she got past security and to the gate, she was told the plane was delayed because of the snow. This caused even more anxiety because she knew all the senior team would be there waiting just for her. As she was waiting to board the plane, she got a call from the school telling her that her youngest son was sick and throwing up. By now her hands were sweating even more, and she began shaking. She had to try to reach her mother and ask her if she could pick up her son. The flight finally took off an hour and a half late. When she arrived, she was able to get a cab and slowly made her way through New York traffic to get to the head office. As she was rehearsing her presentation in her mind and trying to keep calm, she suddenly realized she left behind the handouts that she had prepared for each of the senior team. Now she was in total panic. There was nothing she could do. She never prepared for this many things to go wrong. She now felt completely powerless. How would you feel after a morning like that? Would you be stressed out, or would it be just another day at the office for you? Can you remember the last time you were stressed out? Did it involve a major life event—like an illness or death in the family? Was it work or school related—being judged on a presentation, performance review, or exam? Or financial—not having enough money to meet your goals? Or maybe a relationship problem—not being treated fairly by friends who should know better? Perhaps just the everyday demands on your life are enough to stress you out. How is it that some people are overwhelmed by the slightest disruption or change in their lives, while others seem to make it through catastrophes relatively unscathed? Or that two people, experiencing the exact same event, such as the breakup of a relationship or a serious illness, can react in completely different ways? A colleague of ours, having gone through a similar experience as Belinda’s, had a totally different reaction. As Cathy encountered each new obstacle, she saw it as a challenge, something to problem-solve her way through. She wasn’t worried about failing, but just kept plowing through each new challenge. Perhaps getting a better understanding of stress, and how it works, can help us begin to understand these questions. Once we do, we can begin to learn how to better manage the stress in our own lives, and even turn stress into an advantage! Stress is a necessary part of life. As the early stress researcher Hans Selye once said, the only stress-free person is a dead one (Selye, 1978). Every day we experience challenges that are more or less stressful, causing our bodies and brains to react in characteristic ways. And although this has been true for as long as humans have walked the earth, modern life only seems to be getting more and more stressful. Novel and changing technologies have shifted the way we live and do business. New systems and approaches are appearing at a fast pace, forcing changes in how many jobs get accomplished (Thack & Woodman, 1994). The internet alone has vastly expanded the information available to us, while at the same time opening the door to misinformation, cybercrime, and loss of personal data (Aiken, 2016). Jobs and relationships are less stable. Increasing globalization of operations for many organizations means that employees must learn to function and communicate in strange cultures. Changes are coming more often, and futures are harder to predict. At the same time, stress-related diseases and other problems continue to rise, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, obesity, drug and alcohol abuse, depression, and, yes, suicide. Stress can make you sick, unhappy, and not a very good employee, partner, or parent. In today’s environment, knowing how to cope effectively with stress is more important than ever. Much of the early research on human responses to stress focused on the ill effects of various major life events, such as divorce, a death in the family, or losing your job (Holmes & Rahe, 1967). We hear a lot about the negative effects or the results of “bad stress.” New research, however, is teaching us that not all stress is necessarily bad. One major study, reported in 2012, comes from data collected over a dozen years earlier. Nearly 186 million adults participated in a U.S. National Health Interview in which they were asked dozens of questions about their habits and how they coped with life. These data were later linked to the National Death Index to see if there were any relationships between people’s habits and how long they actually lived. While there are many different causes of death, it was thought that by mining such a large database we could at least provide some clues and perhaps connections between people’s lifestyles and their longevity. It may not be that surprising to learn that 55% of the participants reported experiencing moderate to high levels of stress during the year they were interviewed. If we look at many of the people around us, both at work and in our social and family lives, we’d probably come up with a similar finding. Upon further probing, the researchers discovered that 34% described how this stress had negatively affected their health to some extent during that time. So, while over half of the people surveyed were experiencing high levels of stress, only about a third of them felt it was negatively affecting their health in some way. Later on, the researchers did a follow-up, examining death records and matching them to the people who were interviewed. They made a surprising discovery. Of the people who reported high stress levels, those that said the stress negatively affected their health had a 43% greater chance of premature death. In other words, people who interpret their stress as not having a negative impact on their lives have a better chance of living longer. These researchers went on to find a relationship between people’s coping styles with stress and how long they lived, supporting the idea that it’s not the stress itself that’s bad, but how we manage the stress that’s important. In the words of the study authors, “Stress appraisal plays an important role in determining health outcomes. These findings also suggest that perceived stress and beliefs about the impact of stress on health might work synergistically to increase risk for premature mortality” (Keller, Litzelman, Wisk, Creswell, & Will, 2012). Many other studies have shown that major stressful events can lead to all kinds of serious illness, from heart disease to cancer. But it’s not just the experience of stressful events. Rather, it’s how we appraise or think about these events that seems to matter most. For example, a recent study of California women found that those who perceived prior life events as more stressful were at greater risk for breast cancer, as compared to women who experienced the same events but perceived them as less stressful (Fischer, Ziogas, & Anton-Culver, 2018). As the study authors say, “Perception matters.” It’s a curious fact that people often respond very differently to the same challenging conditions in life. Our colleague Cathy, whom we referred to earlier, reacted quite differently to a situation quite similar to Belinda’s. Cathy, who is very self-confident, likes challenges, yet she still manages to stay in touch with reality. She knows that not all problems are solvable. Perhaps the flight was cancelled, and there was no way to make it for the meeting. While Belinda might blame herself for failing, Cathy would look for alternatives, perhaps a virtual meeting, or try to reschedule. Cathy also reviewed the experience, looking for lessons she could learn from it to improve on the next time she faced a similar situation. For example, she would check the weather the night before. She might arrange in advance for someone else to take the kids to school. She might even leave a day early to make sure weather or other factors didn’t prevent her from getting to the meeting. She realizes that everyone fails sometimes, but it’s what you do with the failure, how you process it, that makes the difference. Bret and Sally were both getting ready to make a presentation at their company town hall meeting. Bret was going to make his first presentation in front of a large group, discussing the financial results of the previous quarter. Sally, also making her first presentation in front of a group, was going to share the company’s marketing plans going forward. They expected about 200 of their fellow employees to be there. You’d never know they were both going to the same meeting. “I am so stressed out,” Sally said. “My hands are shaking, I have butterflies in my stomach, and my heart is racing. I could barely sleep last night.” “Wow, and your skin is pretty pale. You’d better get a glass of water,” Bret responded. “What about you, Bret? You must be nervous. Everyone’s going to be watching,” Sally replied. “Actually, I’m pretty charged! I’ve been working with these new graph templates, and I found some really funny graphics to spice up my slides. I can’t wait to try them out in front of everyone!” he responded, a bit sheepishly, trying to be sensitive to Sally’s unease. How is it that what is anxiety provoking for one person can be exciting for someone else? We find this same thing happens across many areas of life. While for some, a job loss may lead to depression and ruin, others see it as an opportunity to branch out into some new area. Some people seem to routinely cope more effectively with the changes and challenges of life. In recent years, this has been labeled “resilience” (Layne, Warren, Watson, & Shalev, 2007). What accounts for these individual differences? What makes some people more resilient than others when confronting stressful situations? We’ll present you with some of the latest research and provide you with some ways in which you can practice improving your own abilities in this area. At some level we all know that stress has a physical component. We’ve all experienced life’s pressures and how we can react to them both mentally and physically. Whether it’s just a short-term threat or an ongoing number of issues that weigh on our mind, we often feel the stress. What happens to your body when you go into stress mode? Imagine one of your ancestors walking into the jungle and suddenly coming across a lion moving in the opposite direction. The sight of the large beast, and perhaps the slightest eye contact, would most likely send an immediate shock to his system. When the shock first hits, he experiences an acute stress, which triggers his body’s hormones to activate his sympathetic nervous system. Suddenly his adrenal glands release catecholamines, including adrenaline and noradrenaline. This leads to an increase in his heart rate, blood pressure, and breathing rate. His fast heartbeat and breathing help give his body energy to respond. His skin becomes flushed or pale as the blood flow to the surface of his body is decreased so it can go to his muscles, legs, arms, and his brain. As the blood rushes to his brain, his face starts to alternate between pale and flushed. His blood-clotting ability also increases in case he receives any injury that involves blood loss. At the same time as all of this, your ancestor’s body is preparing to be more aware and observant of his surroundings—so he can decide which is the safest way to run. His pupils dilate, allowing more light into his eyes and giving him better vision of his surroundings. His body also immediately starts to tremble or shake, which is the response of his muscles tensing up and being primed for action. This sudden shock he is experiencing was named the “flight or fight” response by American physiologist Walter Cannon (Cannon, 1915). The idea here is that the shock prepares us physiologically and mentally, as described above, to either flee quickly or stand up to the threat and take immediate action against it—usually physically. Hence, the “fight” or “flight.” Alternatively, it was referred to as the first phase of the general adaptation syndrome (GAS) by the previously mentioned physiologist Hans Selye. Once the threat is gone, it may take between 20 and 60 minutes for the body to return to its prearousal levels. It’s this system that has largely allowed us to avoid predators and survive as a species. However, the challenges our ancestors experienced have significantly changed in today’s world. It’s only our response to these challenges that has largely remained the same. Stress, especially when negatively perceived, and chronic, has additional effects on our bodies. The same effects we see in acute stress, such as increased heart rate and blood pressure, over longer periods of time, can produce a chronic wear and tear on the cardiovascular system that can result in disorders such as stroke and heart attacks. Other effects of being “stressed out” include changes in behavior that have been found to be detrimental to health. These include poor sleep, eating or drinking too much, smoking, drug use, and lack of physical activity (McEwen, 2008). All of these can have direct and indirect effects on your ability to live a long and satisfying life. In this book we’ll be exploring positive approaches that people have successfully used to handle the stressful situations in their lives. Some of the techniques we present are well documented in scientific research journals. Others have been developed, used, and modified through our collective work across different environments. Our experience includes people from all walks of life and spans military personnel, students, corporate executives, various workplaces (nonprofit, for-profit, government), lawyers, entertainers, athletes (professional, Olympic, and amateur), managers, frontline workers, leaders, homeless people, and homemakers. This is a book about hardiness, something we believe is an essential ingredient that helps people cope effectively with life stressors, and even thrive under stress. While the supporting evidence behind hardiness is based on over 40 years of scientific research, we don’t intend to bore you with all the technical details. There is plenty of that to be found in professional books and journals. However, we do include numerous references and an index for the interested reader. Rather, our main aim with this book is to explain hardiness in a way that make sense to the average reader, and to provide tips and strategies to improve your own hardiness and your ability to deal with the stresses of life. Over 40 years ago, a University of Chicago graduate student wondered about the different reactions within a group of corporate executives who were going through a major organizational restructuring and downsizing. Suzanne Kobasa wanted to know why some of these executives were getting sick and demoralized, while others seemed to be thriving, all while experiencing the same disruptive and stressful conditions. Later, she published her findings in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Kobasa, 1979). Her research showed that those executives who developed stress-related health problems were lacking in certain personality features when compared to those who stayed healthy through this stressful reorganization. Kobasa called this set of attitudes “hardiness.” Not long after that, one of the authors of this book (Paul) extended this work by looking at a blue-collar sample of Chicago city bus drivers (Bartone, 1984). It turns out that city bus drivers have a pretty stressful job, dealing with traffic, time pressures, and sometimes angry and even violent passengers. His doctoral research showed that these job stressors often lead to a range of health problems, such as hypertension, heart disease, and stomach problems. But those bus drivers who are high in hardiness are largely protected from these problems, staying healthy despite the job stress. Since then, hundreds of studies have confirmed the importance of hardiness as a stress resilience resource that protects people from the bad effects that stress can have on health, happiness, and performance. In the high-hardy person, the three facets of commitment, challenge, and control work together in synchrony, creating a mindset or worldview that is highly effective and makes them resilient in coping with stressful conditions. This constellation of qualities, called hardiness, is found in people who stay healthy and continue to perform well in life, despite experiencing a range of stressful conditions (Bartone, 1999; Bartone, Roland, Picano, & Williams, 2008; Maddi & Kobasa, 1984). People high in hardiness-commitment see life as overall meaningful and worthwhile, even though it sometimes brings pain and disappointment. Hardiness-commitment also includes a striving for personal competence as first described by the Harvard psychologist Robert White (White, 1959). The sense of competence aids the person in making realistic appraisals of novel and stressful situations, and generates increased self-confidence that one can handle adversity. To be high in commitment means looking at the world as interesting and useful, even when things are difficult. These kinds of people pursue their interests with vigor, are deeply involved with their work, and are socially engaged with other people. They are also reflective about themselves and aware of their own feelings and reactions. Low commitment people are often bored and don’t find much meaning in life. They go to school or work or are unemployed with no real game plan or idea of where they want to be in the future. They tend to be unreflective and disengaged, not much interested in their work, themselves, or other people in general. When presented with a challenge, those low in commitment tend to give up easily. Figure 1.1 gives you some examples of how people with different levels of hardiness relate to commitment. Figure 1.1 Where Do You See Yourself on the Commitment Pyramid? People high in hardiness have a strong sense of challenge: they enjoy variety and tend to see change and disruptions in life as interesting opportunities to learn and grow. They understand that problems are a part of life, and they set out to solve them, rather than run away from them. For these people, taking on new challenges is an interesting way to learn about themselves and their own capabilities, while also learning about the world. In contrast, those low in challenge prefer stability and predictability in their lives and tend to avoid new and changing situations. They may be highly reliable, but are not very adaptable when conditions change. Figure 1.2 illustrates how people with different levels of hardiness typically respond to challenges. Figure 1.2 Where Do You See Yourself on the Challenge Pyramid? Hardiness-challenge involves an appreciation for variety and change, and a desire to learn and grow by trying out new things. The main theoretical influences come from work by Fiske and Maddi on the importance of variety in experience (Fiske & Maddi, 1961), and Maddi’s ideas on active engagement in the world (Maddi, 1967). Maddi used the term “ideal identity” to describe the person who lives a vigorous and proactive life, with a desire for variety and new experiences. These people are courageous in choosing to look forward and take action, despite the fact that future outcomes are always uncertain. At the other end of the spectrum is the “existential neurotic,” who shies away from change and always seeks security and predictability in the old and familiar. Control is simply the belief that your own actions make a real difference in the results that follow, that what you do has effects on outcomes. In contrast, people low in hardiness-control generally feel powerless to control or influence events in their lives (see Figure 1.3). Figure 1.3 Where Do You See Yourself on the Control Pyramid? The control facet of hardiness also derives from existential theory. According to Maddi (1989), the core tendency in existential personality theory is “striving for authentic being,” which involves an honest acceptance of yourself and the world around you, and a willingness to make choices and take responsibility for those choices. The authentic (hardy) person regularly chooses the path of engagement and active involvement in the world, instead of the relative safety of passive withdrawal and inaction. High-hardy persons are authentic in this sense, seeing themselves as being in charge of their own destinies, even though the future is always somewhat uncertain and frightening. Being in control is well known to lower the effects of stressful conditions. For example, experimental studies have found that when subjects are given control over aversive stimuli such as electric shocks, the stress effects are reduced, as compared to subjects who have no control (Averill, 1973; Seligman, 1975). In the chapters that follow, we’ll cover each of these facets in more detail and show how you can develop your strengths in each of these areas. We’ll also give examples on how important these facets have been in both successful and unsuccessful attempts to deal with stress in people’s lives. Some of the examples we describe will be of real people you might be familiar with. Other examples will be composites of real-life people and interesting situations that we, the authors, have come across in our work. So let’s get started!

Stress: It’s Unavoidable

Bad Stress, Good Stress: How Knowing the Difference Can Help You Live Longer

People Are Resistant or Resilient to Stress

Your Body’s Response to Stress

Fight or Flight: Our Immediate Response

Stress’s Long-Term Effects on Health

Positive Ways to Handle Stress

Hardiness Can Make a Big Difference in How You Cope with Stress

Introducing the Three Cs

Hardiness and Commitment

Hardiness and Challenge

Hardiness and Control