CHAPTER 7

Getting Yourself More in Control

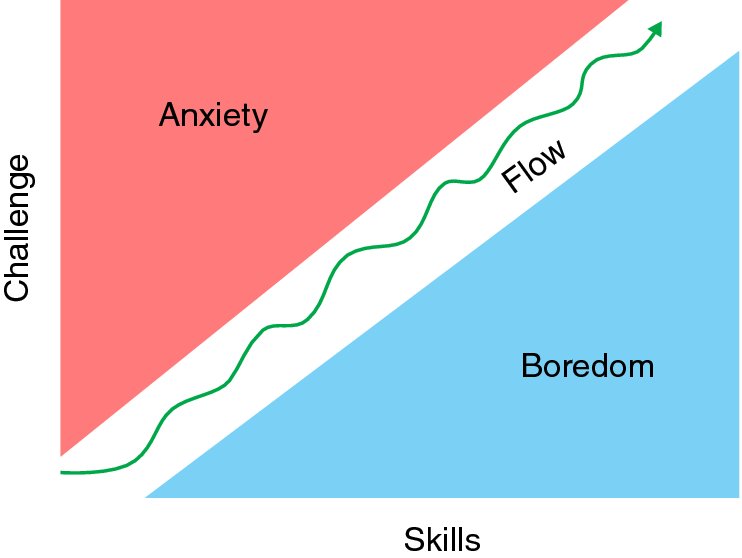

“Control your own destiny or someone else will.” —Jack Welch (American business executive, former chairman and CEO, General Electric) Hardiness-control is the belief that you can control or influence what is happening around you as well as what is going to happen. The opposite of control is a sense of powerlessness or helplessness to do anything that will make a difference. With this in mind, this chapter offers some steps you can apply to increase your sense of control. Jeanine loved her job. She worked in the marketing department of a large agency. It was her dream job. She got to use all her skills and training. The work she did was challenging, and she enjoyed the clients on the accounts she worked on. She even got along well with her boss. However, there was one troubling aspect at her workplace. That was one of her coworkers. The two of them were very different and didn’t see eye to eye on many issues—both at work and outside of work. Jeanine was younger and just hitting her stride professionally. Anne had been at the agency much longer and was somewhat jaded. She wasn’t happy at work or with her personal life. It wasn’t something she managed to hide. Jeanine found her complaining tiresome and distracting from her work. She tried to avoid Anne, but it was difficult in a small office space. Jeanine had tried to get further away from Anne, but as her manager pointed out, there was limited space in the office and nowhere else to go. Her troubles with Anne grew from a distraction to an obsession. Jeanine was starting to find it difficult to focus on her work. She worried about what nonsense Anne might bring to the office next—more complaints about the office, their manager, her lazy daughter, problems with her neighbors—it seemed there was no end to the whining. It also seemed that there was no way for Jeanine to change the situation. She was stuck in the same office with Anne. It finally dawned on Jeanine that she was focusing too much of her time and energy on Anne. It was a situation she couldn’t change. She loved her job and didn’t want to leave it because of one annoying person in the same office. She had to come up with a strategy. She realized she couldn’t control Anne, the physical workspace, or her manager’s lack of attention to the situation. What she could control, however, was her own behavior and her own reactions to Anne’s irritating ways. Rather than wasting countless hours worrying about Anne’s next verbal onslaught, she decided to change her approach. Jeanine came to understand that she had been too passive about Anne’s behavior. She was afraid to speak up or criticize her in any way. It was now time to be assertive. She came up with a number of firm but respectful things she could say to Anne. The goal was not so much to control Anne’s behavior or get even with her, but rather to speak up and get out of her system what was really bothering her. The fact that she was allowing Anne to distract her from her work was the most upsetting aspect of the situation. Some of the statements Jeanine planned on saying included, “Anne, I’m really sorry you are upset with things here, but I’m happy with my work situation and I’d rather not hear any more complaints about work,” and “It’s unfortunate things aren’t going well for you at home right now Anne, but there’s really nothing I can do. It’s really not a good time to unload these problems on me right now. I’ve already got a lot on my plate.” With a little rehearsal Jeanine was able to state her case tactfully and unemotionally. She was fully in control of the message and the way it was delivered. She realized she could not control Anne’s reaction or any changes in Anne’s behaviors. Jeanine was quite surprised that Anne accepted the message and was able to move on. The unpleasant exchanges stopped after that and Jeanine was better able to pay attention to her work. Whether Anne thought any less of her after that exchange became of no consequence to Jeanine. She wasn’t there to win Anne’s friendship or support. She was there to do the work she loved doing. Hardiness-control is about looking at your situation and determining what you can control and what is beyond your control. Knowing how to control the things you have jurisdiction over and taking action is the basis of hardiness-control. In order to focus your attention in the right direction, you first have to stop and think about what your goals are. It’s easy to get distracted in life by things that, in the big picture, are not very important. Once you know what is really meaningful for you in life, it becomes easier to focus on the real prize. Then you can direct your actions and energy towards the things that really matter, as well as the things you really can control, that is, your own thoughts, beliefs, and actions. By taking control of yourself you can gradually better influence others around you. By better managing those around you, you can better influence your community. By having more influence in the community, you are more able to have an effect on the greater environment beyond. This leads to hardiness-control. The psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, in 1995 identified a state of mind referred to as flow. It’s sometimes called “being in the zone.” A state of flow occurs when the challenge slightly exceeds one’s skill level (Csíkszentmihályi, 1990). In other words, when things are not very challenging, you get bored. When they are too challenging, you are likely to get anxious and give up. But, as the Goldilocks rule says, when things are not too hard and not too soft, but just right—your skill is matching or is just below the challenge presented—you can reach the flow state. The flow state has been found to exist in tasks as varied as athletics, playing a musical instrument, acting, solving complex problems, writing a book, climbing a mountain, religious or spiritual experiences, gaming, or any number of activities. The graph representing flow is seen in Figure 7.1. Figure 7.1 Flow Reaching a state of flow requires, of course, knowing your capabilities. Being aware of your level of competence requires you to understand yourself and your level of achievement. Be honest with yourself. Try not to over- or undersell your abilities. Look for objective ways to discover how good you are at something. Get feedback from an objective and trusted person. In some cases, you may be able to get help from automated sources, such as an online assessment. People high in hardiness-control are good at gauging their limits and capabilities. When one of the authors (Steven) returned to music, playing the saxophone after a 30-year hiatus, it was hard to know what level to start at. Most of what had been learned through high school and college had faded away. Fortunately, I found some great music teaching programs online. One program allowed me to play written passages of music while it recorded and graded my performance. Wrong notes and incorrect timing were objectively graded on screen after playing the passages. I could see (and hear) the percentage of mistakes I made in each category. This feedback prevented me from starting at too difficult a level, after which I would have probably given up after sufficient failures, or at too easy a level, after which I would likely have gotten bored. One thing we learned from mindset theory, discussed in Chapter 5, is that we can always continue to grow and improve our performance. The flow theory gives us a bit of a roadmap to success. By knowing your capabilities, selecting the right level of challenge, you can successfully navigate your way through challenges without getting overwhelmed. This helps build your hardiness-control. How often have you found yourself procrastinating on a project? Sometimes it seems so easy to find distractions. One of the toughest things about a new project is getting started. Taking that first step can seem overwhelming. How can you be more efficient and get through the bumps? The first thing you should do is define the project. What is the goal? What are you trying to accomplish? Write a report, analyze a situation, produce a presentation, do a request for proposal, carry out a research project, put together a sales pitch, create a budget, come up with a new idea, or whatever else. Put it down on paper or on your computer screen. This is what I want to do: _____. One of the best ways to overcome inertia is to simply take a first step at the project. It’s important to realize that what you start with is just a draft. Whatever you do can, and likely will be changed. It’s basically a mindset that you have to deal with. No matter how bad your first attempt will be, there is a high probability that your next go at it will be better. In fact, there may be no limit on the times you rework something, although you may have time limits on the project itself. So just jump in! Anything, at this point, is better than nothing! Once you have your description of what you want to do, start breaking it down into pieces or chunks. You should reward yourself every time you complete a chunk. There are a number of ways you can reward yourself do this. You can use a favorite food (if it isn’t bad for your health). I’m (Steven) partial to licorice and wine gums (I know, they’re not healthy). You can take a short walk, exercise, watch a YouTube video, make a call to someone you want to speak with, or pick your own creative, short-term reward. Hardiness-control improves when you know how to self-motivate. In an article published in Harvard Business Review (HBR) researchers surveyed approximately 20,000 professionals across six continents asking specific questions about their productivity (Pozen & Downey, 2019). They came up with a number of general findings—such as working longer hours did not lead to more productivity, working smarter led to accomplishing more each day, older and senior professionals were more productive than younger and more junior colleagues, and overall, men and women were equally productive (although there were some differences in particular habits). There were a number of specific approaches that differentiated the highly productive professionals from those who were less productive. Some of them are relevant here. One of the first was that productive people start with a plan. We’ll get more into that in the next section. If it’s a writing project, start with an outline in a logical order that will help you stay on track. The most productive people create daily routines to help keep themselves on track. So, just like dressing in the morning, or having breakfast, you should set up a routine than ensures you will do some work on your project each day. It could be reading, writing, researching, or whatever activity. It’s important that something gets done each working day. Once again, for hardiness-control to improve it’s important to get used to getting something done. Or, as the shoemaker Nike would put it, “Just Do It!” The HBR survey found that leaving open times in your schedule each day was also a good idea. It wasn’t productive to schedule things too heavily throughout the day. There should always be room for emergencies or unplanned events. One big disruption we all experience today is the constant barrage of incoming emails. Many of us tend to stop what we’re doing and jump over to read them upon arrival. Rather than checking them as they come in, it was found to be more productive if you check them once every hour or less. Also, skip over most of your messages by just looking at the sender and the subject line. Only those deemed to be important and needing an immediate response should be tended to in the moment. The rest can wait until you have more time on your hands. Pedro never liked to plan before starting a project. He just couldn’t wait to jump right in and give it all he had. He knew how to get things started, and he believed once he got going there was no stopping him. That was true up to a point. His enthusiasm and energy took him far, but he seemed to always have trouble completing projects. He would either tire out eventually, run into a roadblock, or run out of ideas for the next phase of the project. At that point he felt dejected, defeated, and lost. When tasks have multiple components, or stages, we are better off planning them out. Think about the amount of time we might need, whether it can be broken into smaller steps, and what resources are needed. You wouldn’t build a house without a set of plans or a blueprint. When it comes to projects, the level of planning can vary. For smaller projects it might just be outlining the steps we need to go through. Larger projects may need more detail in planning. Writing a book is a good example of a longer-term project. Before we wrote this book, for example, we mapped out the chapters with temporary titles. Then we filled in each chapter heading with a brief paragraph outlining what we planned to cover. Then we put together a page describing the book overall and what we hoped to accomplish with it. This is important for the publisher who might consider publishing it, as well as for us as authors in that it helps us complete the writing process. While mapping out the chapters, we started to think of the content, some of the research we might need to include, how to access it, perhaps some case examples, and so on. Whenever we got stuck or blocked in our writing, we referred back to the detailed outline to get back on track. Almost any project, proposal, or venture can benefit from a plan. It helps you anticipate the challenges and opportunities that lie ahead. It also helps you prepare for them in advance. Surprises are good for birthdays, but don’t always work out well when trying to complete a project. The plan doesn’t have to be elaborate, just enough to think through the process. Know where you begin and where you end. By doing more planning you build your hardiness-control as you learn more of which actions are within your control and which may be beyond your reach. There’s new evidence that setting goals can be good for your mental health as well. A study done by psychologists at the Pennsylvania State University followed over 3,000 adults for over 18 years. The researchers collected data over three time periods from 1995 to 2013. The subjects were asked about their approach to setting goals as well as their ability to master challenges in their lives. At each interval they were also assessed for depression, anxiety, and panic disorders. It turns out that the people who showed the most goal persistence and optimism during the first assessment in the mid-1990s had less depression, anxiety, and panic disorders over the 18 years. Also, the people who started with the lowest depression, anxiety, and panic disorders showed more perseverance towards their life goals and were better at focusing on the positive sides of negative life events. In the words of the study authors, “Our findings suggest that people can improve their mental health by raising or maintaining high levels of tenacity, resilience and optimism …. Aspiring toward personal and career goals can make people feel like their lives have meaning. On the other hand, disengaging from striving toward those aims or having a cynical attitude can have high mental health costs” (Zainal & Newman, 2019). Another interesting finding of the study had to do with self- mastery. Here this was the belief that you could do anything you set your mind to. Unlike some previous studies, findings showed that believing you had ultimate control was not related to people’s mental health. Also, the amount of control people felt they had over their lives did not change much over the entire time period. This led the authors to suggest that self-control is a trait—or a stable part of personality that does not change. We don’t fully agree with that. We believe your hardiness- control can change. But what the study more likely indicates is that it does not change on its own or naturally. Unless you make a concerted effort to change the way you see yourself controlling your behavior (through coaching, therapy, or experiential learning), it likely won’t change. Also, hardiness-control does not mean that you have ultimate control or that you can change anything you set your mind to. People high in hardiness-control feel a strong sense of personal control—and they plan ahead—but they know their limits. They don’t have unrealistic expectations of control. For example, I know I can always change my feelings, thoughts, and behaviors in a situation. But I can’t always change the situation. The changes I can make may not be dramatic, but they may lead to reinterpreting the (stressful) situation I am experiencing. If I’m in the jungle, and I come upon a hungry tiger, I will most certainly be filled with fear. I know I can’t “will” the tiger to go away, but I can decide whether to freeze in fear (and get eaten) or run for dear life (and hope I escape). If I interpret the situation as hopeless, I’m more likely to experience the former. If I interpret it as “I have a chance to live,” I’ll experience the latter. Hardiness-control is about helping you make these kinds of life decisions. By learning how to plan, you get better at visualizing different scenarios and making better decisions. How do you know when you need help? There’s a fine balance between independence and asking for help. Some people are constantly asking others to help them out. Others, even when they don’t know what they’re doing or where they’re going, refuse to listen to anyone else. Brad was the president of a young, fast-growing technology company one of the authors (Steven) met while giving a presentation at the Young Presidents’ Organization (YPO). This is a worldwide organization whose members are all under 45 years of age and presidents of companies worth more than $20,000,000 or with sales of over $10,000,000 per year. A very impressive group. The topic of the presentation was emotional intelligence and leadership. After the Q&A and discussion, Brad approached me privately. He wanted to tell me how unimportant emotional intelligence was in his success. In fact, he said, he owed all his success to his high IQ. He was the one who created the software that his company sold. He did all the marketing, the sales, managed the accounting, trained users on his product, did technical support, and was in charge of all the hiring and firing decisions. It wasn’t clear when he had time to sleep, but he got across the point that he was a very busy person. It was important for him to do all these functions, he reported, because there was no one else as capable as he was in any of these areas. In fact, he was giving me quite a dressing down, especially around my point of hiring the best people you can find to be responsible for all of these roles in your organization. I had pointed out how successful entrepreneurs such as Bill Gates and Michael Dell had made a point of hiring great talent in their companies and letting them run their departments. As Brad went on about his own special talents, his 2IC (second in command, a young woman named Nancy) stood by patiently listening. When he finished his tirade, he took off to the bar, not even waiting for my response. “Don’t pay attention to a thing he’s saying,” Nancy piped up after he left. “I have to work with him every day. He’s a disaster in each of those areas. The reason he has to run them is because nobody else can work with him. He doesn’t listen to anyone and now the company is suffering. We can’t keep good people.” “He owes a lot of money to the banks, our sales are down, and I don’t know if I’ll be there that much longer. Thank you for your talk; you hit the nail on the head. Only, I was hoping he would see it.” Once again, we see the results of over-control or too much self-mastery. Hardiness-control is about knowing your limits and behaving accordingly. If Brad was strong in hardiness-control, rather than taking personal charge of so many functions and spreading himself too thin, he would focus on finding the right people for each position he needed so that he could focus on his strengths. Leaders high in hardiness-control are confident in knowing they control the company and know they can control who runs each division and how it is run. But it is over-control, and perhaps too much ego, to believe that you can directly control all of these complicated functions by yourself. You don’t have to manage everything personally to be in control. Getting advice from others is not a weakness; it is a strength. Coaching of executives is now one of the fastest growing careers in the corporate world. From once being seen as a bit embarrassing, having an executive coach, like having a personal trainer, is now a badge of honor. Many of the most successful corporate leaders today work with an executive coach and welcome the guidance and advice they receive. Many leaders have told us that not only do they get good advice on management issues, it helps relieve the stress of having few people to talk to at the top. Coaching increases confidence in decisions, which helps build hardiness-control. Mariana was the first female vice president at one of the largest financial institutions in the country. She was a role model for women throughout the industry. She had broken through the glass ceiling in an industry that had always been male dominated. She worked her way up from a line position to the executive suite over many years of hard work. Having spent some of her career in the human resources area, she had an interest in people and what made them tick. As part of exploring that interest, she agreed to undergo a battery of psychological assessments to better understand how it might apply in the workplace. Among those assessments, she took the Emotional Quotient Inventory 2.0 (EQ-i 2.0), which is the world’s first and most widely used measure of emotional intelligence. Expecting her to score at the highest levels across the board, we were quite surprised with the results. While Mariana had a number of very high scores, including empathy, assertiveness, and interpersonal relationships, she had one particularly low score. That was in self-regard. Self-regard includes knowing yourself, your strengths and challenges, as well as having self-confidence. How could this be? We first thought it might be a scoring error. How could someone who achieved so much in her career express such a low level of self-regard? When asked about the assessment, Mariana was in full agreement with the results. It was her interpersonal skills and ability to listen and understand others that got her to where she was. However, she believed she was not deserving of any special accolades, as she saw herself as “just doing my job.” When we explained that she had accomplished so much, that she was seen as a role model for so many, she downplayed the whole notion. After exploring this for some time, she finally came to see that what she had accomplished was, in fact, unique. And, even more important, by acknowledging her success she could be tremendously helpful to hundreds of other women as an inspirational role model. This put the situation in a totally different light. We’ve encountered a number of women high achievers in the corporate world who downplay their success. For many of them it boils down to not recognizing past successes. Part of coaching these women has involved recognizing and acknowledging past successes. It has meant going through their careers, identifying milestones, celebrating those milestones, and connecting them to other successes. What we find is that these successes are not random, and they don’t happen by luck. Hardiness-control includes realizing you have been responsible for certain actions that have gotten you to where you are. One way of reinforcing this is by consciously recognizing successes and celebrating them. This doesn’t mean arrogance. It just means honestly seeing your own positive achievements. By acknowledging your contributions to your successes, you become more aware of the connections between actions and results. Solidifying this relationship helps build your hardiness-control. By increasing Mariana’s hardiness-control, we were able to help her connect the dots between her hard work and the successes she achieved. This changed her perception of herself. As a result, she was able to increase her self-regard scores on the EQ-i 2.0. But even more importantly, she became much more active as a role model for other women in her industry. She gave more public talks and became more involved in mentoring other women with high potential in her own financial institution. What should you do when you have a problem and there doesn’t seem to be a solution? Sometimes we encounter situations that are beyond our control. We can continue working away at it, hoping something will change, or we can take a more realistic view of the situation and change direction. Being strong in hardiness-control includes realizing what you have the power to change and what lies beyond your control. The one thing we can always control is our reaction to situations. By managing our thoughts, we can influence our emotions and behaviors. It’s what we say to ourselves about situations that determines our feelings and actions. Mario and Claude were both business development reps at a midwestern manufacturing company. The company had been going through some tough times over the past several years. A decision was made from the corporate headquarters to close down the midwestern division. Mario and Claude had very different reactions. Mario felt the closure was totally unjustified. He immediately petitioned to meet with his boss and the regional vice president to make his views known. He put all his energy into preparing historical sales data, market history, economic predictions, and other pertinent information related to their industry and the local plant. He created an impressive slide deck hoping to convince the VP of sales to help overturn the decision. Claude took a very different tack. He immediately found his resume and updated it. He enlisted the help of an executive recruiter to refresh the look and feel of it and help him chart a new path. Within a couple of weeks Claude was booking interviews with other manufacturing plants. He worked on his interview skills, researched the companies he was interviewing for, and received a couple of offers in a month’s time. While Mario gave a valiant effort at presenting the virtues of their plant to the regional VP, it was all for naught. The decision was made at corporate headquarters, and there was no turning back. He felt dejected and went into a mild depression. On the other hand, Claude was preparing for a new start and was getting more and more excited about the challenges that lay ahead. There could not be two more different reactions to the same situation. Both Mario and Claude felt an initial shock upon hearing about the closure. The first night was a sleepless one for both of them. But when morning came, they had channeled their energy into two entirely different directions. Mario convinced himself he could save the company. His job was everything to him. He focused on what he could do to change a major corporate decision. Claude read the situation differently. He saw the writing on the wall. His goal was to move on and find some other option that would be fulfilling, and financially viable, for him. Hardiness-control includes reading situations, understanding what’s controllable, and taking appropriate action. It is not about blindly chasing dreams. Once you have a plan, and it is actionable, high hardiness-control people do what they can to achieve their goals. They know which levers they can pull and which ones are out of reach. When one lever is stuck, they find another one that opens the door. In the following chapters we will provide you with hardiness-related information on special topics. We suggest you continue working your way through these sections. Even if you’re not particularly athletic or you don’t perform in front of others, you may find some of the lessons worth exploring. What we learn from high-performance athletes, successful entertainers, or flourishing business leaders can be helpful to you and the people you know.

Focus Your Time and Energy on Things You Can Control or Influence

Work on Tasks That Are Within Your Capabilities, Moderately Difficult but Not Overwhelming

For Difficult Jobs, Break Them Up into Manageable Pieces So You Can See the Progress

Plan Ahead and Gather Up the Right Tools and Resources for the Task

The Benefit of Setting Goals

Knowing What You Can and Can’t Control

Ask for Help When You Need It

Recognize Your Successes

When You Just Cannot Solve a Problem, Turn Your Attention to Other Things You Can Control