CHAPTER 9

Hardiness at Work

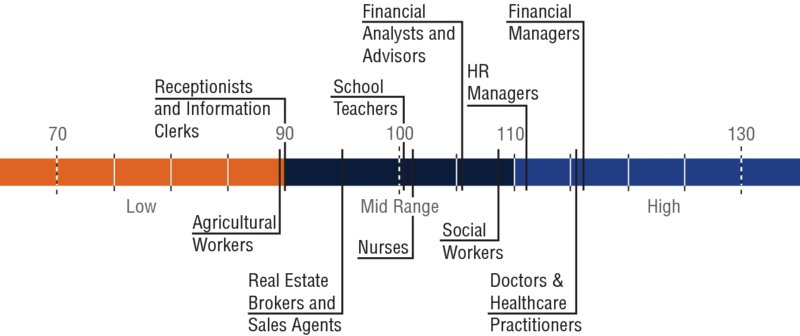

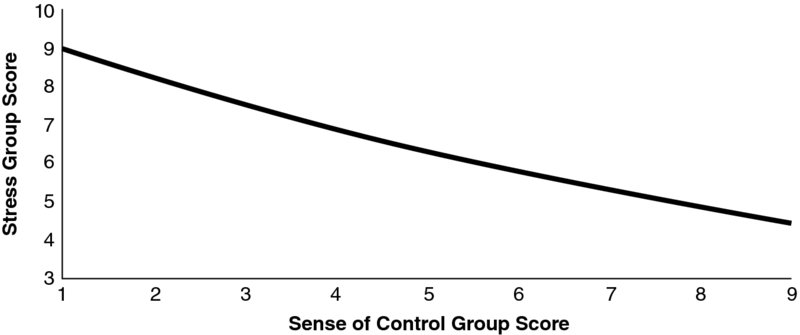

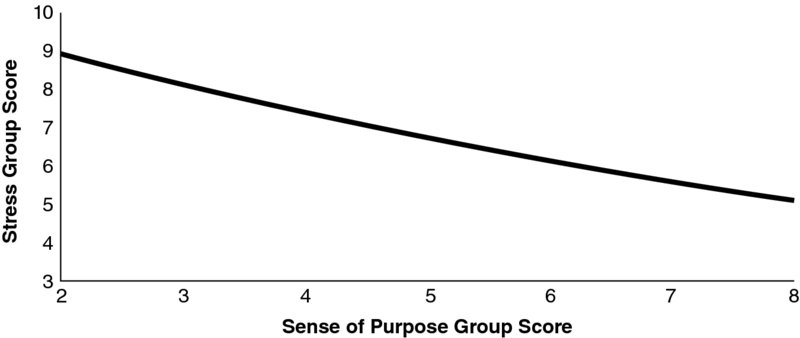

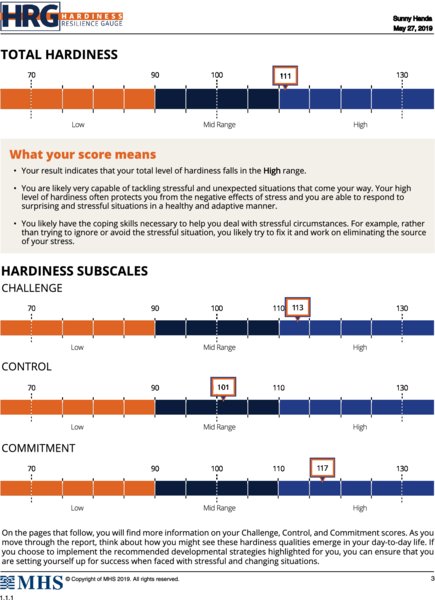

“The big secret in life is that there is no big secret. Whatever your goal, you can get there if you’re willing to work.” — Oprah Winfrey (US talk show host, media executive) Are you stressed out in your current job? Have you ever thought about how stressful other jobs might be? What would you think are some of the most stressful jobs out there? Does bus driver come up as one of your choices? In this chapter we’ll talk about stress in the workplace. By learning how hardiness applies to work, you’ll have the tools to better understand how you can improve your work situation. You may want to change your hardiness mindset to better fit your job, or you may want to find a job that’s more suited to your current hardiness mindset. This chapter will help you chart your course. Driving a bus can be a stressful job. In fact, it can be one of the most stressful jobs out there. There are some great rewards for driving a bus—decent pay, good family medical benefits, and a decent pension. But the costs can take their toll. Some of these costs have been documented by Christine Zook, who was president of Amalgamated Transit Union Local 192 in Oakland, California (Boyer & Brunet, 1996; DelVechio, 2019). Zook, who drove a bus for an urban transit district in Northern California, describes her work as squeezing a 20-ton machine through city streets filled with traffic jams, potholes, road construction, jaywalkers, bike messengers, double-parked trucks, and often careless motorists. Driving a city bus had taken its toll on her. The job’s day-to-day stresses on her body and nerves had built up over the years and left her with clenched muscles and crying spells. According to Zook, bus drivers tend to die young. The stress takes a toll on their lives. There has been over 50 years of research across different countries looking at the effects of driving buses for a living. One of the findings is that urban bus drivers experience higher than average rates of cardiovascular disease, according to a study in the Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. “Epidemiological data from samples in several different countries consistently find urban bus drivers among the most unhealthy of occupational groups, particularly with respect to cardiovascular, gastrointestinal and musculoskeletal disorders,” the researchers reported. “Further, cardiovascular mortality rates are directly linked to years of service as a driver” (Evans & Johansson, 1998). This study found that bus drivers are likely to have high blood pressure and increased levels of stress hormones—factors that contribute to sickness and death from heart and blood vessel problems. In addition, these drivers are exposed to whole-body vibration, diesel exhaust, and noise while keeping themselves in a combat-like state of vigilance in order to deal with threatening passengers and crazy motorists. As if this weren’t enough, bus drivers must adhere to a brutal schedule of stops or risk being disciplined or fired. Bus drivers have also been found to be at greater risk of post-traumatic stress disorder than the population at large. This is based on a Montreal study of transit operators (Boyer & Brunet, 1996). Bus operators are always expected to be ready with a smile for the customer, a quick memory for transit information for those who ask, and a helping hand for bicyclists and the disabled. City bus drivers also have multiple demands placed on them. They are expected to be on time and follow strict schedules according to their managers. They have no control over traffic and weather conditions. There is little discretion in how they carry out their jobs. They tend to be in a hierarchically structured workplace. As well, they must deal with demands of passengers, regardless of how unreasonable, providing service with a smile. Studying bus drivers is what led one of us (Paul) into the area of hardiness back in the late 1980’s (Bartone, 1989). At the time there was a growing amount of research looking at the stress that people in white-collar jobs were experiencing. The research on people in office jobs began to spread to a variety of different jobs, including air traffic controllers, airline pilots, dentists, engineers, and scientists. No one, however, was looking at blue-collar workers such as bus drivers. Researchers were starting to suggest that a number of blue-collar jobs would, in fact, be more stressful than many white-collar jobs. For example, there were reports of London bus drivers who worked in the center of the city having more coronary heart disease issues when compared with suburban bus drivers. Other studies looking at bus drivers found that there were high rates of absenteeism, employee turnover, debilitating illness, injuries on duty, and claims for health benefits. There may be many reasons for these effects, but stress was thought to be one of the leading factors. Much of the stress was attributed to things like time pressure, traffic noise and congestion, equipment vibration, air pollution, lack of control over working conditions, and the social isolation of the bus driver from his or her coworkers. One of the things I (Paul) found interesting at the time was that not all of the bus drivers’ responses to stress were negative. As we have seen in many other occupational groups, the relationship between stress and illness is not a simple one. Just like in other occupations, bus drivers showed a range of responses to stress. My interest at the time was, and is to this day, what differentiates people who experience negative effects from stress from the ones who don’t have these bad effects. So, the question I wanted to answer is what are the qualities that distinguish bus drivers with high stress who get ill from bus divers with high stress who manage to stay healthy? Understanding this can help us develop effective programs for reducing the negative effects of stress. And this is what I have been studying for the past 30+ years. These lessons can be applied across many different high-stress occupations. Bus drivers were a logical group for me to study, for I had some personal experience with the job. While a graduate student at the University of Chicago, I worked as a bus driver for the Chicago Transit Authority. So, I’d experienced the job stressors firsthand. I observed many of my fellow bus drivers who seemed anxious and burned out, while others appeared happy and well adjusted. I wanted to find out why, if they’re all dealing with the same basic job demands and stressors, are they reacting so differently? After the Chicago Transit Authority refused to let me survey drivers, I turned to the bus drivers’ union, Amalgamated Transit Union Local #241. When I briefed the union president Elcosie Gresham on the study, he was immediately supportive. Mr. Gresham had also been a bus driver and had experienced the stress of the job. He confided in me that during his time as a driver, a pedestrian was killed when she slipped under the wheels of his bus in a snowstorm. Traumatized by this incident, he gave up driving and devoted his life to getting better working conditions for bus drivers. Basically, the research study involved assessing 798 active bus drivers. They were all surveyed about their stress at work, as well as any stressful life events they were experiencing, their methods of coping, their current health status, any psychiatric symptoms, health habits, their social support, as well as their current level of hardiness. Based on all the information that was collected, we were able to divide these bus drivers into two groups. The first group had high levels of stress and were experiencing a lot of illnesses or negative symptoms. The second group included bus drivers who were also experiencing high levels of stress, but they had few illnesses or unhealthy symptoms. The goal of the study was to find out what factors differentiated these two groups of bus drivers. Several sophisticated statistical analyses were carried out in order to pinpoint these differences. It turns out there were three factors that made a significant difference: A sense of commitment, either to the work, to themselves, or to others, was the main hardiness factor moderating the negative effects of stress. The driver who believes that he or she is doing something important and meaningful has the best protection against the damaging effects of stress. When interviewed, these drivers spoke with great pride about the work they did, which was described as moving passengers safely to their destinations. For the other drivers, those more prone to suffer from stressful situations, they felt that driving the bus was “just a job.” Challenge was not found to be as important as commitment for the health of these bus drivers. However, other occupations which may have less routine to them, such as advertising or sales, might find challenge more valuable. These types of occupations allow for more creative and risky choices in the work. A sense of control may be more important for people who have jobs in which they can define their own schedules, activities, and the nature of the work itself. Certain highly scheduled or routinized jobs may favor people with low levels of internal control. For example, one study found this was the case for offshore oil rig workers. The work is quite repetitive and allows for little deviation from the routine (Cooper & Sutherland, 1987). A sense of control may also be important in situations where there may not be much opportunity to influence events, and where a sense of meaning or commitment is severely threatened or not able to be fully expressed. In these cases, one can only choose one’s mental attitude. Examples of this can be found in more routine jobs like fast food workers, baristas, or house cleaners. Family support is often cited as an antidote for stress. Interestingly, in our Chicago bus driver study family social support was not a significant protective factor. One reason may be that social support from family members can sometimes be the kind that encourages withdrawal or avoiding the stressful situations at work (Kobasa & Puccetti, 1983). On the other hand, social support from coworkers was found to be a important factor in reducing the negative effects of work stress. Coworkers may be more helpful in fostering active coping strategies, if they can support you in confronting and dealing with stressful situations at work. We’ve collected hardiness data from thousands of people around the world. In this section we’ll look at how hardiness differs in some occupational groups that we found interesting. Figure 9.1 shows some of these differences across jobs. Figure 9.1 Hardiness in Different Occupational Groups (Used with permission from Multi-Health Systems, 2019.)

While these occupational profiles are revealing, it’s important to remember that we’re reporting average hardiness scores here. Within each group, whether farmers or doctors, there is individual variability. Some farmers are high in hardiness, and some doctors are low. No matter what your job is, you can still be high in hardiness and maintain a strong sense of challenge, control, and commitment. However, you might find it a bit stifling if you are high in hardiness and are in a job that doesn’t provide you with opportunities to exercise your style. So, does your hardiness level influence your career choice? Most likely the answer is yes, to some degree. For example, some people decide early on that they want a career in which they believe they will control their own destiny, such as entrepreneurs, doctors, dentists, entertainers, writers, and others. On the other hand, some people are happier applying for a steady, more routine job, such as receptionist, clerk, fast food worker, bank teller, and so on. Hopefully, we select jobs that “fit” our hardiness type. When we end up with a job that doesn’t fit our hardiness type—such as a person with high control and commitment taking a routine job that doesn’t allow for much control, or something to believe in—we may feel a disconnect. Either you would adjust your mindset or find another, more satisfying job. The healthcare profession has long been identified as a stressful line of work. Speculation as to the causes of stress has included the complexity of professional activities, chronic staff shortages, the requirement to provide quality care, emotional overload, role conflicts, and noise, all making work in a hospital more painful and increasingly stressful. Researchers have started to look into why some healthcare professionals exposed to these conditions are still highly effective, while others have professional difficulties. One interesting study carried out at a large hospital setting in Morocco set out to profile the hardiness levels of their healthcare professionals—150 nurses and 80 doctors (Chtibi, Ahami, Azzaoui, Khadmaoui, & Mammad, 2018). The study used an earlier version of the Hardiness Resilience Gauge (HRG) as one of its measures. They found no difference in hardiness levels of nurses compared to doctors. Length of service, however, was a factor. Healthcare professionals who had worked at the hospital longer scored higher in hardiness than those who started more recently. Is hardiness related to the health status of these medical professionals? This study addressed this question by looking at certain health indices in the hospital staff. Health conditions included hypertension and cancer. Seventy-eight percent of those who reported hypertension fell in the lowest group of hardiness. In addition, those professionals who had cancer were in the lowest scoring hardiness group. Overall, most of these healthcare professionals, 81%, scored in the lowest third of hardiness; 16% scored in the middle group; and only 3% were in the high resilience group. Another measure the researchers looked at was the level of engagement of these professionals in their work. There was a significant relationship between how engaged they were in their work and their hardiness levels, with the hardier people being more engaged. The authors report that engagement allows doctors and nurses to get involved in their work and to adapt positively in the professional context. The hardiness-control factor was important in looking at different options for taking action when needed. The hardiness-challenge factor reflects the involvement of healthcare professionals in the process of change. The authors go on to discuss the importance of these resilience factors in protecting healthcare professionals from work-related stress. Resilient professionals can cope positively with stressful events, while vulnerable people tend to see stressful situations as threatening. Low hardiness professionals tend to reject change and prefer stability. We can see how these findings may apply to different work groups. Having a high hardiness level in a job that allows for independence, fosters purpose, and offers challenges will make it easier to become more engaged in your work. When you see room for change at work, being high in control helps you make it happen. Your challenge level can make the change happen more smoothly. Most people tend to settle into situations and types of work that will provoke certain kinds of emotional reactions. In an overview of three decades of research on hardiness, Celina Oliver had some interesting conclusions about hardiness and work satisfaction (Oliver, 2009). Because people differ, they generally seek out the kind of work that provides the emotional responses that are best suited for them. For example, people high in hardiness prefer work that provides a lot of independence and more challenging opportunities. Hardy people are more likely to change situations that they see as undesirable. They are more inclined to present a can-do attitude in their work. Also, they are more likely to seek feedback at work, which increases their competency as well as their self-esteem and self-confidence. Hardy people are more likely to set and reach stretch goals. In the workplace people who are high in hardiness, when they encounter stressful situations, tend to engage in effective problem-focused coping strategies. Or, when there are limited opportunities to change the situation, they will know how to reframe it—that is, look at it from a more positive viewpoint. They are more likely to count their blessings rather than dwell on the unpleasantness of the situation or vent their feelings about the unfairness of it all. Oliver’s review looked at the relationship between hardiness and job satisfaction in a variety of different occupational groups. Hardiness was found to be more strongly related to job satisfaction in jobs such as teaching, healthcare, and human services. In other words, jobs that involved helping or developing people had a stronger relationship between hardiness and job satisfaction. So, people low in hardiness may struggle when they work in jobs that involve a lot of interaction with other people. This may relate to some of the other findings about hardiness at work. Hardiness-commitment was found to have the strongest relationship with overall work satisfaction. People who have a purpose in life either find the work that is most satisfying to them, or make the most of the jobs they already have. The relationship between control-hardiness and satisfaction was significant, but not as strong. People who are higher in control tend to make the changes they need in order to be more satisfied at work. Either they find ways to make changes in their existing job, or they go out and find a more satisfying job. Challenge-hardiness, while also related to overall job satisfaction, was not as strong as the other two factors. People higher in this area would likely look at their jobs and redefine what they do as interesting, focusing on those parts of their job that they find the most challenging. Think about your own level of hardiness-commitment. Have you identified the things in life that are most important to you? Is it helping people, improving the environment, creating new things, making the world a better place? Identifying your purpose and finding work that supports that cause will lead you to greater satisfaction both at work and in life. What happens when you are asked to do something new at work? Are you likely to treat it as a new challenge, something you’re excited about? Or do you see this kind of request as a burden or a hassle that just gets in the way of other work? Some people view any new request at work as a drain on their resources, leading to an increase in work stress. Other people view these requests as new opportunities, or the kind of challenges we have described in previous chapters. Researchers have built work theories around these perceptions. In one framework, these requests are seen as depleting your resources, adding more stress to your life. In another, some demands are seen as challenges, yet others may be hindrances, or merely interferences with ongoing work. In a study of these two models, researchers have gone one step further, looking at how these kinds of work demands influence workers in two ways—their own sense of self-worth and the perceived meaningfulness of their work (Kim & Beehr, 2019). This then leads to a concept that is described as flourishing—an increase in general positive well-being. Flourishing, more specifically, has been defined as having feelings of competence, positive relationships with others, and having purpose in life. People high in the hardiness mindset are more likely to be in a flourishing state. Researchers have looked especially at the effects of three categories of work demands. The first is workload. This has to do with how hard you have to work. The second is responsibility. This is where there is a lot that depends on decisions that you make. The third is learning demands. This relates to how much you need to learn in order to improve the knowledge and skills you need to do your job. Most important in these studies is how workers view the demands that are made of them. If someone asks you to do something, and you appraise or judge it as interesting or challenging, that will lead to one set of effects. If, on the other hand, you view the same requests as annoying, or a hindrance, that can affect you in a completely different way. Your entire sense of self-worth and the meaningfulness of your work can be influenced by how you see these demands, either positively or negatively. One of the surprising findings of the research is how these work demands—and your interpretation of them—can spill over into your personal life outside of work. While we all want to strive for work-life balance (if there is such a thing!) and leave our work issues in the workplace once we go home, this doesn’t seem to happen. We carry our feelings from work with us into our personal worlds. If we feel excited and challenged by what we have done at work, we’re more likely to be in a good mood and flourish at home. If we are drained and stressed out by our experience at work, we take those bad feelings—along with the health risks they produce—and suffer at home. While we have often heard about the negative effects of work—stress, daily hassles, heavy workloads, interpersonal conflicts—and how they can affect our health, we have rarely, if ever, heard about the positive effects. Higher hardiness, which includes looking at demands as challenges, having commitment to your mission, and having control over your tasks, can lead to increased flourishing in your life overall, including greater feelings of competence, positive relationships with others, and increased purpose in life. We’ve covered some of the challenges that blue-collar workers, such as bus drivers, must grapple with and how hardiness can play a role in a healthier life. We also looked at professionals in the healthcare field. One of the professional groups that experiences a lot of stress is lawyers. In fact, it’s been reported that not only do lawyers encounter more psychological distress than the general public, but they are in poor mental health with higher incidents of depression, alcoholism, illegal drug use, and divorce than almost any other profession (Beck, Sales, & Benjamin, 1995–96; Allan, 1997; Shellenbarger, 2007). In one of the earliest studies to look at stress and health in lawyers, Suzanne Kobasa surveyed a group of 157 general practice lawyers who attended a meeting of the Canadian Bar Association (Kobasa, 1982). For these lawyers, stress contributed significantly to symptoms of strain and illness such as heartburn, upset stomach, headaches, and trouble sleeping. More important, the study showed that those lawyers who were high in hardiness-commitment, and low in the use of avoidance coping strategies, were healthier and less likely to experience these stress-related health problems. Another interesting study carried out at the University of Alabama Law School investigated the relationship between hardiness, stress, and a number of other factors in lawyers and law students (Pierson, Hamilton, Pepper, & Root, 2018). They started out talking about the “lawyer personality.” Because of the nature of law school admissions, it’s difficult to gain admittance to a law school with an IQ lower than 115. As well, the profession attracts people who are motivated, intelligent, and ambitious. They tend to be more achievement-oriented, aggressive, and competitive than in other professions. The “lawyer personality” also implies that lawyers are less willing to accept help when they need it. They tend to be self-reliant, ambitious, perfectionistic, and highly motivated to provide good service. In a British study of 1,000 lawyers it was reported that 70% of them said they experienced their workplace as stressful; two-thirds said they would “be concerned about reporting feelings of stress to an employer” (Lyon, 2015). One of the reasons for this is the fear of damaging their reputation and subsequently their client base. Sometimes people high in certain aspects of hardiness, such as hardiness-commitment, will continue pursuing their purpose even though they may be hurting or overstressed. That’s where challenge comes in as a balancing factor. A strong sense of challenge increases mental flexibility. People high in challenge can more easily shift directions and take a different approach or path when one isn’t working. The lawyer’s lifestyle contributes towards stress as well. The work usually demands long hours. There is a great deal of pressure on attaining enough billable hours. The adversarial nature of the job can also add to the stress. There is a lot of unpredictability in the outcome of cases that can take hundreds of hours to prepare for. Lawyers often have to deal with difficult clients, coworkers, and opponents. In the Alabama Law School study, Pierson et al. surveyed 530 lawyers and law students about their work, stress, and how they manage it, along with administering some personality tests. The researchers included an earlier version of the Hardiness Resilience Gauge (HRG) measuring challenge, control, and commitment, as well as overall hardiness. Lawyers from throughout Alabama as well as a national group were invited to participate in the study. The goal was to obtain a stress score for each respondent, identify the behavioral patterns of respondents who had lower and higher stress scores, and determine if any of their behavior patterns correlated with stress levels. The researchers first analyzed the relationships between all responses to individual questions to identify the characteristics of a stress-hardy lawyer. They then cross-tabulated each survey response with all the other survey responses. They looked at relationships that were statistically significant, including demographic variables. A number of the lawyers were interviewed as well. The results showed highly significant relationships among certain characteristics. For example, the lawyers’ sense of control, sense of purpose, cognitive flexibility, and stress hardiness were related. This means that lawyers who had a greater sense of control, sense of purpose, or cognitive flexibility were less stressed, while those who had lower control, sense of purpose, or cognitive flexibility were more stressed. They also found a highly significant relationship between relying on alcohol and drug use to manage stress and stress levels experienced: those lawyers who reported relying on substance use to manage their stress were in turn more stressed. The lawyers encountered a variety of stressors based on their areas of specialty. Lawyers who represented people in either family or criminal law often found it difficult dealing with people when things didn’t go well for them—such as going to jail or losing custody of a child. Lawyers involved in litigation often had trouble dealing with difficult people, especially the lawyers on the opposing side. Managers of law firms were often stressed by dealing with the personnel issues within their firms. Lawyers who worked in government worried about not having the resources they needed to succeed in their work. The Alabama law school study found direct relationships between stress and the hardiness factors of control. For example, as seen in Figure 9.2, lawyers who experienced more stress had a lower sense of control, and those with the least stress had the highest sense of control. This was found to be related to the unpredictability of their work. Unexpected curve balls seem to go along with the practice of law. Figure 9.2 Sense of Control Versus Stress in Lawyers (Copyright 2017. All rights reserved. Used with permission from Pamela Bucy Pierson, University of Alabama School of Law.) One of the interesting things about this study was that they asked the lawyers to describe how they coped with stress. Responses from the hardy lawyers, related to control, were quite interesting. Seven themes emerged as to how lawyers adapt and maintain a sense of control over their professional lives. These are: Hardiness-commitment, which the researchers referred to as sense of purpose, was also found to be directly related to stress in lawyers. This is shown in Figure 9.3. Figure 9.3 Sense of Purpose/Commitment Versus Stress in Lawyers (Copyright 2017. All rights reserved. Used with permission from Pamela Bucy Pierson, University of Alabama School of Law.) Purpose was expressed by a number of the lawyers as helping or making a difference in clients’ lives. Other examples included unraveling problems, protecting companies, gratitude of clients, helping the legal system render justice, and helping the legal system work better. Overall, the lawyers who reported no sense of purpose had an average stress group score 32% higher than the average stress score of lawyers who had at least some meaningful aspects of practicing law. The study also looked at hardiness-challenge which was referred to as cognitive flexibility. Basically, this was described as a way to make stressful situations make sense. It is described as the ability to pivot, take a different route, or change goals when dealing with a stressful situation. They found that lawyers who had the highest stress were the least cognitively flexible, and those with the least stress were the most flexible. This is shown in Figure 9.4 Figure 9.4 Cognitive Flexibility/Challenge Versus Stress in Lawyers (Copyright 2017. All rights reserved. Used with permission from Pamela Bucy Pierson, University of Alabama School of Law.) For example, lawyers who reported that they were “not bothered by interruptions to their daily routine” were more confident about their ability to handle personal problems and better able to control irritations in life. Lawyers who enjoy the challenge of doing more than one thing at a time were more likely to feel on top of things. Flexibility and adaptability were qualities that the lawyers high in challenge endorsed. Lawyers who excelled in challenge/cognitive flexibility had strategies that fell into eight general categories: Many of these strategies can be applied beyond the legal profession. Sunny Handa is a senior partner at one of Canada’s largest law firms. He heads up the firm’s information technology group and the communications group. With a doctoral degree in law he also teaches at the Faculty of Law at McGill University and has written books on computer and intellectual property law. He has been selected among the top lawyers in his field according to several independent lists and rankings of Canada’s top lawyers. His clients include some of the world’s largest technology companies. Sunny’s Hardiness Resilience Gauge scores are shown in Figure 9.5. Figure 9.5 Sunny Handa’s Hardiness-Resilience Scores As you can see, Sunny’s overall hardiness score is in the high range. There’s no surprise here. Throughout his law career he’s made it through many tough negotiating situations, but he seldom, if ever, gets riled or loses his cool. His hardiness-challenge score is high as well. When asked about his score, he explained that he feels he is high in confidence because he is comfortable with the unknown. That’s a big part of hardiness-challenge. He does not fear whatever unfamiliar situations may be coming down the road, but rather, sees them as interesting problems to be solved. He also sees himself as a bit lazy, as he has such an academic background. He feels his challenge is influenced by his education and experience. It helps that he teaches new lawyers. New lawyers tend to be scared when presented with tricky situations. He teaches them that if you know the law you can find the answer to frame any problem. All you have to do is break it down into pieces. It’s not about the solution, it’s about how to get there. When he’s confronted with a difficult case, he uses his gut and can usually determine very quickly where the case is likely to go. At his level of practice and clientele, he deals with very smart people. It’s the nature of his work. We were surprised that Sunny’s hardiness-control score was lower than expected. But when asked about this he said that it made perfect sense to him. He stated that his world is very complex as it involves dealing with a lot of chaos. He has to navigate these situations with the tools and skills that he has. In his world, only 10% of what happens is changeable, making one feel that there is a limited range of control. Going with the flow is often the best option. The parties generally know what they want, and his job is to work within certain parameters. He sees his job as executing and minimizing the risk. As he states it, “I have to decide where we spend our time. I am a libertarian. Many things are out of our control.” Sunny’s hardiness-commitment score is his highest. When you talk with Sunny about his work it’s understandable. As he puts it, “I believe in the work I do. I am driven by the work I do. I love the work that I do. I feel blessed to be alive. I like people and I love working with people. I also like to spend time alone. If everything I dealt with was rational, I wouldn’t have a job. I never feel deflated. My faith in my work is very exciting. Every case is exciting to me. Even if I’ve done a similar case, I find the next one exciting. There are always twists in these kinds of cases.” When we look at Sunny’s emotional intelligence scores we also find a very elevated profile. He scores highest in self-regard. This factor has to do with your self-confidence and your ability to know your strengths and weaknesses. As he states it himself, “I feel confident in myself. I don’t mean to overstate it; I don’t mean be arrogant.” His next highest score is in empathy. This is the ability to understand people—both their thoughts and feelings—from the other person’s point of view. This is especially important for lawyers trying to understand not only their client but their adversaries’ perspective. Lawyers also have to know how far they can go in pushing the limits in a courtroom. For example, as Sunny puts it, “I like to hear people out. I think everybody has a valid point of view to express.” The third highest score is in optimism. In emotional intelligence terms, this is the ability to see the positive side of things, even in difficult times. When confronting overly complex and difficult cases, it can be easy to get overwhelmed, especially when the stakes are so high. A certain degree of optimism is needed not only to keep your client happy, but to drive your own belief that you can arrive at a solution. In his own words, “I think things will work out okay. I have a positive view.” When we look at emotional intelligence, we also look at the challenges that people have. In Sunny’s case one of the lower scores in his profile was in the area of social responsibility. This has to do with our commitment to helping others in need. It’s not that he’s low in social responsibility, but rather it is less of a priority than most other areas. He explains his score as, “I am a Libertarian. I feel there’s a difference between self-interest and greed. Society won’t help me; I need to help myself. I will be socially responsible where I have a personal connection.” A second area of challenge is his flexibility. This is an area that tends to be lower, especially for rule-bound professionals such as lawyers, engineers, and accountants. As Sunny says, “I work within the rules. I tend to support management. I am interested in fairness.” As we have seen in this chapter, hardiness-commitment can be a very important part of buffering you from workplace stress. Looking for meaning in your work can not only help you better manage stress but can keep you more engaged in the work you do. It also helps if you build social support among your coworkers. Your coworkers can be a very important sounding board to help you let off steam about frustrating work situations. The whole idea of the hardiness mindset and how it fits for certain careers is something you can think about. If you have a good idea of where you are in terms of your need for challenge, control, and commitment, you can see how that might apply in various jobs. For example, if you have a high need for control you may want to work in an environment that gives you that latitude. If more meaningful work is important for you, you can look for a job that lets you feel like you are making a contribution to society. If what you look for is challenge, you can find work that offers lots of variety, keeps your mind sharp, and/or keeps your body engaged. Your priority might be jobs with challenging assignments. Generally, people in jobs that involve helping people in one way or another such as teaching, nursing, social work, medicine, and so on have higher levels of hardiness than people in other, less people-oriented jobs. We don’t know for sure whether hardier people choose these kinds of jobs, or time spent in a people-helping job makes you hardier. The answer is most likely some combination of both. In the healthcare field, length of time in the job was related to greater hardiness. It could be that for many types of work the longer we’re there, the more we develop a hardiness mindset. We start feeling more in control, gravitate to more challenging tasks, and find more meaning in our work. Hardiness is also related to engagement. If we have greater control over our work, we have more choice in how we get things done. This sense of control helps increase our engagement and commitment. And we also see that hardiness helps protect these healthcare professionals from stress. Rather than having the stress mindset (that change is a threat), the hardiness mindset (change is interesting and challenging) drives these people in their daily activities. To what degree do you operate from a stress mindset versus a hardiness mindset? Do you see changes in your world as threatening or as interesting challenges? So now you have a few examples of areas of work where hardiness has been found to be important. You can apply much of this to your own work. We’ll be exploring hardiness in some other walks of life in the following chapters.

Driving a Bus Is No Walk in the Park

Getting Overwhelmed by Multiple Demands

Stress in Bus Drivers: Why Some Stay Healthy and Others Get Sick

Does Hardiness Influence Your Career Choice?

Hardiness Scores of Healthcare Professionals

What Do We Know About Hardiness and Work Satisfaction?

Challenges Versus Hindrances at Work

Practicing Hardiness in the Legal Profession

The Relationship Between Control and Stress

The Relationship Between Purpose (Commitment) and Stress

The Relationship Between Cognitive Flexibility (Challenge) and Stress

Profile of the High-Hardiness Lawyer

Putting Your Hardiness to Work